Chronic infantile neurological cutaneous articular (CINCA) syndrome, also known as neonatal‐onset multisystem inflammatory disease, is a rare congenital inflammatory disease characterised by cardinal signs including a variable congenital maculopapular urticarial rash, chronic non‐inflammatory arthropathy with abnormal cartilage proliferation, and chronic meningitis with progressive neurological impairment associated with polymorphonuclear and occasionally eosinophilic infiltration.1 The CINCA syndrome is associated with childhood uveitis and papillitis with chronic disc swelling.2 It may occur as a result of mutations of the CIAS1 gene that encodes cryopyrin, which results in reduced apoptosis of the inflammatory cells with up regulation of interleukin 1 (IL1).3,4,5 Consequently, the CINCA syndrome responds poorly to immunosuppressives including steroids, and treatment has been limited until recent reports of successful treatment with the recombinant human IL1 receptor antagonist (rHuIL1Ra), anakinra (Kineret, Amgen, Thousand Oaks, California).6,7,8,9,10 We report the case of successful treatment with rHuIL1Ra of a patient with refractory CINCA‐associated uveitis.

Case report

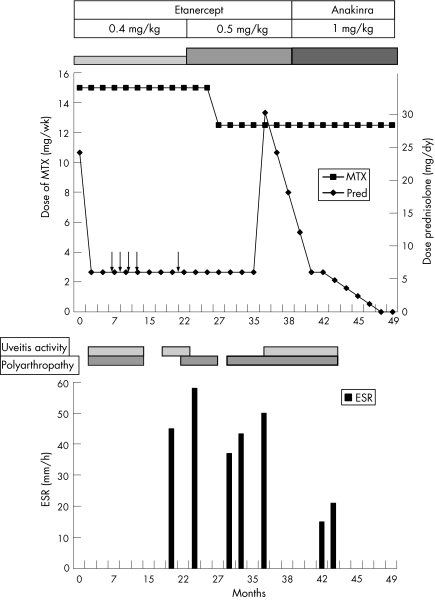

Over a 2‐year period, a 4‐year‐old boy developed increasing signs and symptoms diagnostic of the CINCA syndrome. With the advent of increasing polyarthropathy and bilateral panuveitis, he was initially treated with courses of steroids alongside subcutaneous methotrexate 15 mg/week (table 1, fig 1). The course of uveitis included bilateral panuveitis, more severe in the right eye with hypopyon, which was treated with intensive topical steroids while maintaining on oral prednisolone 5 mg/day and methotrexate. Visual Snellen acuity was 6/12 in both eyes, and although the anterior uveitis was improving, bilateral disc swelling and vitritis persisted. He had no vasculitis or cystoid macular oedema. Despite bimonthly intravenous methylprednisolone pulses and methotrexate, both the uveitis and polyarthropathy remained active, and he was therefore started on anti‐tumour necrosis factor (TNF) treatment, with subcutaneous etanercept 0.4 mg/kg twice a week. Concomitant immunosuppression included methotrexate 12.5 mg/week and 5 mg/day prednisolone. Over the following 2 years, further relapses of uveitis with disc swelling and vitritis associated with only partial improvement of his arthropathy necessitated increase in dosage of etanercept to 0.5 mg/kg, but with no benefit. In 2005, treatment with rHuIL1Ra (anakinra) was started at a dose of 1 mg/kg/day, inducing remission. At his last review in 2006 (aged 8 years), his uveitis remained quiescent with resolved vitritis and disc swelling, and permitted withdrawal of oral prednisolone. Vision remains 6/9 in the right eye and 6/18 in the left, with normal intraocular pressures. There remains optic disc pallor as described in CINCA‐associated uveitis associated with the CINCA syndrome.

Table 1 Summary of progress and condition over time.

| Year | Age | ESR (mm/h) | Visual acuity | Disease activity* | Optic nerve head swelling | Systemic disease ‐ active polyarthropathy† | Systemic immunosuppressive agents | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OD | OS | OD | OS | OD | OS | |||||

| 1999 | 1 | NA | NA | Y (Hypopyon) | Y | NA | Y | Ibuprofen | ||

| 2002 | 4 | NA | NA | Y | Y | NA | Y | MTX 15 mg/week, prednisolone 5 mg od, intermittent courses of IVMP 6‐8 weekly, ibuprofen 200 mg 3 times daily | ||

| 2003 | 5 | 45 | 6/6 | 6/6 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Etanercept 0.4 mg twice/week, MTX 15 mg/week, prednisolone 5 mg od, ibuprofen 200 mg three times daily |

| 2004 | 6 | 58 | 6/12 | 6/12 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Etanercept 0.5 mg twice/week, MTX 15 mg/wk, prednisolone 5 mg od |

| 2005 | 7 | 50 | 6/9 | 6/12 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Stopped etanercept, anakinra 1 mg/kg/day, MTX 12.5 mg/week, prednisolone 5 mg od with slow taper |

| 2006 | 8 | 21 | 6/9 | 6/18 | N | N | N | N | N | Anakinra 1 mg/kg/day, MTX 12.5 mg/week |

ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; IVMP, intravenous pulses of methylprednisolone; MTX, methotrexate; N, no; NA, information not available; Y, yes.

*Activity defined as per Standardisation of Uveitis Nomenclature guideline with respect to vitritis11,12.

†Polyarthropathy was the main systemic feature of activity.

Figure 1 Drugs and disease activity over time. Time 0 = July 2002. Arrows indicate intravenous pulse methylprednisolone. MTX, methotrexate; Pred, prednisolone; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Uveitis activity: anterior uveitis or vitritis activity ⩾1 (SUN guidelines)11 with or without disc swelling.

Discussion

The use of biologicals to more exquisitely and specifically target immune responses has delivered dramatic responses in patients with ocular inflammatory disease.13 The use of biologicals, particularly the anti‐TNFα agent infliximab, in refractory uveitis is well reported.14,15,16 Anakinra is a recombinant non‐glycosylated homologue of HuIL1Ra, a natural immunomodulating molecule, which competitively inhibits binding of IL1α and IL1β to the IL1 receptor type 1, which is expressed in a wide variety of tissues and organs.17 Successful treatment of systemic, cutaneous, neurological and articular manifestations has been reported in IL1‐mediated inflammatory disease such as the CINCA syndrome,6,7,8,9,10 refractory rheumatoid arthritis18 and relapsing polychondritis resistant to anti‐TNFα treatment.19 The paradigm of tailored treatment is now possible because of increased understanding of immune responses, as exemplified by successful treatment of patients with anti‐TNF‐resistant systemic‐onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis, who show IL1 predominant lymphocyte responses in vitro with rHu IL1Ra treatment.20

The rationales for use of anakinra and not infliximab in our patient were: (1) clinical evidence that the CINCA syndrome is an IL1‐mediated inflammatory disorder; (2) the patient already showed resistance to anti‐TNF treatment of systemic as well as ophthalmic manifestations; and (3) experimental evidence of suppression of experimental models of uveitis with anti‐IL1 treatment.21,22 The rapid and favourable resolution of posterior uveitis and disc swelling on institution of anakinra treatment in our patient supports an IL1‐mediated uveitis in association with the CINCA syndrome. Matsubayashi et al5 also noted resolution of papill oedema (although no uveitis was present) with the use of anakinra when treating a patient with intractable arthropathy. Anakinra increases the available biological options and should be considered for the treatment of anti‐TNF refractory juvenile idiopathic arthritis‐associated uveitis and defined groups of patients with IL1‐driven disease (CINCA syndrome) or risk factors that preclude the use of anti‐TNFα agents, as described for rheumatic diseases.18

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Prieur A M. CINCA syndrome. Orphanet encyclopedia. http://www.orpha.net/data/patho/GB/uk‐cinca.pdf (accessed 7 Nov 2006)

- 2.Sadiq S A, Gregson R M, Downes R N. The CINCA syndrome: a rare cause of uveitis in childhood. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus 19963359–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feldmann J, Prieur A M, Quartier P.et al Chronic infantile neurological cutaneous and articular syndrome is caused by mutations in CIAS1, a gene highly expressed in polymorphonuclear cells and chondrocytes. Am J Hum Genet 200271198–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aksentijevich I, Nowak M, Mallah M.et al De novo CIAS1 mutations, cytokine activation and evidence for genetic heterogeneity in patients with neonatal‐onset multisystem inflammatory disease (NOMID); a new member of the expanding family of pyrin‐associated autoinflammatory disease. Arthritis Rheum 2002463340–3348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matsubayashi T, Suguira H, Arai T.et al Anakinra therapy for CINCA syndrome with a novel mutation in exon 4 of the CIAS1 gene. Acta Pediatr 20069246–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Granel B, Serratrice J, Disdiem P.et al Dramatic improvement with anakinra in a case of chronic infantile neurological cutaneous and articular (CINCA) syndrome. Rheumatol 200544689–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hawkins P N, Bybee A, Aganna E.et al Response to anakinra in a de novo case of neonatal‐onset multisystem inflammatory disease [letter]. Arthritis Rheum 2004502708–2709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frenkel J, Wulffraat N M, Kuis W. Anakinra in mutation‐negative NOMID/CINCA syndrome: comment on the articles by Hawkins et al and Hoffman and Patel. Arthritis Rheum 2004503738–3739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Callegas J L, Oliver J, Martín J.et al Anakinra in mutation‐negative CINCA syndrome. Clin Rheumatol. 2006;1–2 (epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Dinarello C A. Blocking IL‐1 in systemic inflammation. J Exp Med 20052011355–1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jabs D A, Nussenblatt R B, Rosenbaum J T. The Standardisation of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Working Group. Standardisation of uveitis nomenclature for reporting clinical data: results of the First International Workshop, Am J Ophthalmol 2005140509–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benezra D, Forrester J V, Nussenblatt R B.et al Uveitis scoring system. Berlin: Springer, 1991

- 13.Lim L, Suhler E B, Smith J R. Biologic therapies for inflammatory eye disease. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 200634365–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kahn P, Weiss M, Imundo L F.et al Favorable response to high‐dose infliximab for refractory childhood uveitis. Ophthalmology 2006113864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suhler E B, Smith J R, Wertheim M S.et al A prospective trial of infliximab therapy for refractory uveitis: preliminary safety and efficacy outcomes. Arch Ophthalmol 2005123903–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tugal‐Tutkun I, Mudun A, Urganiciolgu M.et al Efficacy of infliximab in the treatment of uveitis that is resistant to the combination of azathioprine, cyclosporine and corticosteroids in Behcet's disease: an open‐label trial. Arthritis Rheum 2005522478–2484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hannum C H, Wilcox C J, Arend W P.et al Interleukin‐1 receptor antagonist activity of a human interleukin‐1 inhibitor. Nature 1990343336–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Konttinen L, Kankaanpää E, Luosujärvi R.et al Effectiveness of anakinra in rheumatic disease in patients naïve to biological drugs or previously on TNF blocking drugs: an observational study. Clin Rheumatol 200625882–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vounotrypidis P, Sakellariou G T, Zisopoulous D.et al Refractory relapsing polychondritis: rapid and sustained response in the treatment with an IL‐1 receptor antagonist (anakinra). Rheumatology 200645491–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pascual V, Allantaz F, Arce E.et al Role of interleukin‐1 (IL‐1) in the pathogenesis of systemic onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis and clinical response to IL‐1 blockade. J Exp Med 20052011479–1486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosenbaum J T, Boney R S. Activity of interleukin 1 receptor antagonist in rabbit models of uveitis. Arch Ophthalmol 1992110547–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lim W K, Fujimoto C, Ursea R.et al Suppression of immune‐mediated ocular inflammation in mice by inerluekin‐1 receptor analogue administration. Arch Ophthalmol 2005123967–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]