Abstract

Early detection of the onset or progression of macular disease is likely to become increasingly important as new treatment modalities are introduced. Current best practice involves issuing patients with an Amsler chart for daily or weekly observation with the instruction to attend for immediate assessment should any new distortion be perceived. However the sensitivity of Amsler charts in detecting macular disease can be less than 50%, implying that presentation may be delayed in over half of patients with advancing disease relying on the Amsler chart to detect progression. A likely explanation for this is the phenomenon of perceptual completion whereby regular objects are “filled‐in” across the scotoma. Although alternative tests have been developed and shown to have greater sensitivity, at present no straightforward, cheap, home‐based test of macular disease progression is available. The development of such a self‐diagnostic tool should be a research priority.

Background

With the introduction of new treatment modalities for age‐related macular disease (AMD), early detection of the progression of macular disease is crucial. Unlike the previous use of ablative laser photocoagulation, new treatments have the potential to preserve foveal function. In addition to more established therapies such as photodynamic therapy and macular translocation surgery, a number of new treatments are in the later phases of clinical trials, including intravitreal injection of anti‐angiogenics1,2 and angiostatic agents.3 One common feature of these interventions is that early treatment is required. The ability of patients to accurately detect changes in their vision and seek immediate referral is therefore of paramount importance. Since the late 1960s it has been recommended to give patients at risk of AMD an Amsler chart to detect early changes in their visual status, with the normal instruction to attend immediately should new metamorphopsia or scotoma be identified.4

The amsler chart

The Amsler charts, first described in 1947 by the Swiss ophthalmologist Marc Amsler5,6 are thought to have been inspired by a grid designed by Landolt7. A similar chart comprising parallel lines with a central fixation spot used to determine the presence of metamorphopsia was described in 18747,8 and Amsler reports a paper from 1894 which consists of parallel lines to determine “metamorphoma”.9

When viewed from the recommended distance of 30 cm, the Amsler chart subtends 20°, with each small square corresponding to one degree of visual angle. Patients are asked a series of structured questions whilst viewing the chart monocularly.

The complete set of Amsler charts consists of seven plates: the conventional white‐on‐black grid with and without diagonal lines to aid fixation; a red‐on‐black version; a version with dots in place of lines; a version with lines in only one orientation (rather than a grid); a version with black lines on a white background; and a chart with smaller 0.5° squares in the central region.10

Limitations of the Amsler chart as a screening tool

Any diagnostic tool must have an acceptable level of specificity and sensitivity. Poor specificity (that is, where a high proportion of subjects are identified as having a disease when they are healthy, associated with a high false positive rate) overburdens secondary health care systems and cause unnecessary distress. Conversely, poor sensitivity (failure to identify patients who do have the disease, linked to a high proportion of false negative results) can lead to patients not being offered treatment when it would be most appropriate.

The Amsler chart has been shown to indicate the presence of scotomas in about 2% of control subjects without any scotoma.11 More significantly, the sensitivity of the Amsler chart has been shown to be as low as 56% in one study when compared to the more accurate method of fundus microperimetry.12 Schuchard also found that in patients with smaller scotomas (of less than 6° diameter), the false negative rate rose to 77%. Other authors have shown sensitivity of the Amsler chart for the detection of AMD to vary between 9% in early AMD and 34% in late AMD with choroidal neovascularization.11 It is clear from these data that a significant proportion of patients with macular disease will not be identified by using the Amsler chart alone.

Whilst the bulk of these studies have examined the detection of scotomas, in the earlier stages of AMD distortion may precede scotoma development. The sensitivity of the Amsler chart to detect new distortion is, therefore, of great importance. In only five of 49 patients examined by Fine and colleagues was Amsler distortion the first reported visual symptom, yet under close supervision 44 of the 49 did report abnormality on the Amsler chart, raising the importance of patient education and concordance.13

In the absence of Amsler chart changes, patients with new vision loss from macular disease tend to be identified through referral from optometrists, general medical practitioners, or opportunistic clinic review; or to present with other visual symptoms.14 Even amongst those patients who do detect change on an Amsler chart, only three‐fifths followed advice correctly and attended an ophthalmology emergency department directly (rather then first attending an optometrist or their general practitioners).14

Why does the Amsler chart produce such a high level of false negative results? There are several possible explanations such as the use of a preferred retinal locus away from the scotoma boundary,15,16,17 averaging of crowded stimuli18 and asymmetry of attentional deployment in peripheral retina.19 However the most compelling reason for this poor success rate is the phenomenon of filling‐in.

Filling‐in

Filling‐in, or perceptual completion, is a well established phenomenon whereby visual features are perceived in the absence of neural input, on the basis of surrounding features. This is most commonly demonstrated over the physiological blind spot: even under monocular conditions no “hole” is visible in the visual field. In 1832, Sir David Brewster wrote:

“Though the base of the optic nerve is insensible to light that falls directly upon it, yet it has been made susceptible of receiving luminous impressions from the parts which surround it, and…the spot…in place of being black, has always the same colour as the ground”20,21

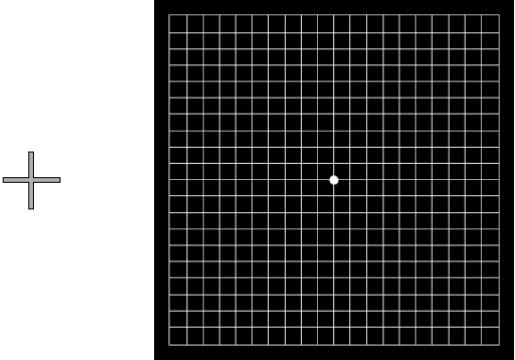

A straightforward illustration of this for the non‐visually impaired reader is to fixate five degrees to the left of an Amsler chart with the left eye covered (towards the cross in fig 1): no scotoma is seen to correspond with the physiological blind spot.

Figure 1 A demonstration of the phenomenon of filling‐in. With the left eye closed, fixate the grey cross whilst observing the Amsler chart from approximately 25 cm. No gaps in the lines are observed despite the projection of the physiological blind spot into the grid.

Although it is reasonable to assume that a different cortical mechanism is responsible for filling‐in in the case of acquired (rather than physiological) scotomas,22,23 there is evidence that filling‐in occurs across pathological scotomas24,25 and in healthy subjects with simulated scotomas.26 The fact that filling‐in occurs across simulated scotomas is significant: it suggests that filling‐in can occur immediately rather than being an adaptive process which develops over a long timescale, although perceptual completion is thought to be more pronounced in established “real” scotomas than in simulated scotomas.27

Improving the Amsler chart

The most frequently used version of the Amsler grid for patients to use at home is a photocopied black‐on‐white form of the chart (as chart 5 in the original set of charts). At least one UK pharmaceutical company prints pads of charts in this format and several macular disease charities have them available on their websites. However, a recent evaluation of these two chart formats (black‐on‐white compared to white‐on‐black) in 182 patients found the original version of the chart (that is, with white lines on a black background) to produce more obvious distortion and scotoma.28 Unfortunately these authors did not report sensitivity of either Amsler chart.

Threshold Amsler testing involves asking the patient to view the white on black version of the chart through cross polarizing filters, reducing the luminance of the grid.29 This has been shown to improve scotoma detection in patients with diabetic retinopathy: in 26 patients, 22 had scotomas detected with the threshold Amsler chart yet only four of these were detected using the conventional Amsler chart.30 Unfortunately it is not known whether all these patients actually did have scotomas: some of the results may have been false positives. This makes it impossible to calculate the specificity of the thresholding chart from this study. When comparing both the TA‐300 threshold Amsler chart and the conventional Amsler chart presentation to a gold standard of SLO microperimetry, Schuchard found a less impressive improvement: the threshold chart increased the detection rate of absolute scotomas from 59% to 63%, and from 56% to 61% in patients with relative scotomas.12

Another modification of the Amsler chart which has been reported is to present it as blue grid on a yellow background, or in various other colours.31 To the best of our knowledge no data on sensitivity or specificity for these charts have been published in the peer‐reviewed literature. In the 1980's Yannuzzi suggested the introduction of a credit‐card sized Amsler chart (for “our highly mobile society”), although this chart was slightly less sensitive than the conventional Amsler grid.32 In the future it may be wise to introduce macular disease screening tests for viewing on a portable computer, personal digital assistant or mobile telephone.

Replacing the Amsler chart

The Preferential Hyperacuity Perimeter (PHP) is a computer based screening test. The test works on the principle of hyperacuity and involves tachistoscopic presentation of a “virtual line” of dots presented on a computer monitor. The patient is asked to report any misalignment, blur or gaps within the line. The fast stimulus presentation reduces the likelihood of patients using a preferred retinal locus to observe the target. In a study of 108 patients with macular disease and relatively good acuity (6/60 or better), 87 (81%) were identified using the PHP and 24 (23%) using the Amsler chart. However, specificity of the PHP is lower than the Amsler chart: 6% of control subjects failed the PHP test.11

A multicentre investigation of the PHP has produced similar results: of 150 patients with relatively good visual acuity (6/48 or better), 68% of patients with AMD were correctly identified.33 However, this study found a high false negative rate: 18% of control subjects failed the PHP. A further multicentre study using a commercially available version of the PHP (PreView PHP, Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dublin, CA, USA) of 185 patients found sensitivity of 82% and sensitivity of 88%, although 11 patients produced unreliable PHP readings.34

A further limitation of the PHP is its reliance on the ability to use a computer mouse or keyboard. The PHP can only be used as a home‐based test if the patient owns a PC, and just 6% of older people living alone in the UK own a computer.35

Another high‐technology solution is the Virtual Retinal Display system described by Plummer and colleagues.36 This system combines a scanning laser device with a virtual reality display, and projects dynamic visual noise – a randomly moving field of pixels. Scotomas are perceived as areas without target motion. The authors report a sensitivity of 82% and a specificity of 100% for a group of 91 patients with known age‐related macular degeneration. Once again the expense of this equipment and the training required in reporting scotomas make it impractical as a home‐based screening tool, yet it could be incorporated as part of a general health screening programme.37

A further computer based screening test which has been suggested is the Macular Mapping Test,38 yet sensitivity and specificity data on this test are yet to be published in the peer‐reviewed literature.

A simple, cheap, easy to use screening test which patients can use in their own home, which is highly sensitive and specific for development or progression of AMD has yet to be developed. Such a system would facilitate early identification and presentation of patients with developing macular disease, with potentially large public health benefits.

Conclusions

As more and better treatments become available for neovascular AMD, the importance of early detection of patients who may be amenable to treatment becomes more critical. Although the Amsler chart has the benefit of being straightforward, cheap and easily understood by patients, the very high false negative rate means that great care must be taken in interpreting a negative result. Until a suitable replacement is available, it is suggested that the Amsler chart is given to all patients considered at risk of developing macular disease and careful and precise instruction given in its use. However, the maxim “absence of evidence is not evidence of absence” must be considered when interpreting Amsler chart reports.

Acknowledgements

Funding: MDC and GSR are part supported by MRC grant G0401339.

The authors would like to thank Dr Peter Bex for helpful discussion, and Dr Janet Sunness for constructive comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript.

Abbreviations

AMD - age‐related macular disease

DMEM - Dulbecco's modified essential medium

PHP - Preferential Hyperacuity Perimeter

Footnotes

Competing interests: none

References

- 1.Chang T S, Tonnu I Q, Globe D R.et al Longitudinal changes in self‐reported visual functioning in AMD patients ‐ in a randomised controlled phase I/II trial of lucentis (TM) (ranizumab, rHuFAB v2). Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45: ARVO E‐Abstract, 3098

- 2.Moshfeghi A A, Puliafito C A. Pegaptanib sodium for the treatment of neovascular age‐related macular degeneration. Expert opinion on Investigational Drugs 200514671–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmidt‐Erfurth U, Michels S, Michels R.et al Anecortave acetate for the treatment of subfoveal choroidal neovascularization secondary to age‐related macular degeneration. European journal of ophthalmology 200515482–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schlaegel T F, Cofield D D, Clark G.et al Photocoagulation and other therapy for histoplasmic choroiditis: An etiologic survey of 100 patients. Ophthalmology 196879355–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amsler M. L'examen qualitatif de la fonction maculaire. Ophthalmologica 1947114248–261. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amsler M. Earliest symptoms of diseases of the macula. Brit J Ophthalmol 195337521–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marmor M F. A brief history of macular grids: From Thomas Reid to Edvard Munch and Marc Amsler. Survey of Ophthalmology 200044343–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Forster R. Zur klinischen Kenntniss des Choroiditis syphilitica. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 18742033–82. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mackay G. Ophthal Rev. 1894;13:83. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amsler M.Amsler charts manual. London: Hamblin Instruments, 1949

- 11.Loewenstein A, Malach R, Goldstein M.et al Replacing the Amsler grid ‐ a new method for monitoring patients with age‐related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology 2003110966–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schuchard R A. Validity and interpretation of amsler grid reports. Arch Ophthalmol 1993111776–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fine A M, Elman M J, Ebert E M.et al Earliest symptoms caused by neovascular membranes in the macula. Arch Ophthalmol 1986104513–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zaidi F H, Cheong‐Leen R, Gair E J.et al The Amsler chart is of doubtful value in retinal screening for early laser therapy of subretinal membranes. The West London Survey. Eye 200418503–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Timberlake G T, Mainster M A, Peli E.et al Reading with a macular scotoma. I. Retinal location of scotoma and fixation area. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1986271137–1147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sunness J S, Applegate C A, Haselwood D.et al Fixation patterns and reading rates in eyes with central scotomas from advanced atrophic age‐related macular degeneration and Stargardt disease. Ophthalmology 19961031458–1466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crossland M D, Culham L E, Kabanarou S A.et al Preferred retinal locus development in patients with macular disease. Ophthalmology 20051121579–1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parkes L, Lund J, Angelucci A.et al Compulsory averaging of crowded orientation signals in human vision. Nat Neurosci 20014739–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.He S, Cavanagh P, Intriligator J. Attentional resolution and the locus of visual awareness. Nature 1996383(6598)334–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brewster D. Letters on natural magic, addressed to Sir Walter Scott. London: John Murray, 1832

- 21.Walls G L. The filling‐in process. Am J Optom Arch Am Acad Optom 195431329–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Komatsu H. The neural mechanisms of perceptual filling‐in. Nature reviews neuroscience 20067220–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Safran A B, Landis T. From cortical plasticity to unawareness of visual field defects. J Neurophthalmol 19991984–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gerrits H J M, Timmerman G J M E N. The filling‐in process in patients with retinal scotomata. Vision res 19699439–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schuchard R A. Perceptual Completion of Patterns across Scotomas. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 1993341420–1420. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramachandran V S, Gregory R L. Perceptual filling in of artificially induced scotomas in human vision. Nature 1991350699–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zur D, Ullman S. Filling‐in of retinal scotomas. Vision Res 200343971–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Augustin A J, Offermann I, Lutz J.et al Comparison of the original Amsler grid with the modified Amsler grid: Result for patients with age‐related macular degeneration. Retina 200525443–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wall M, Sadun A A. Threshold Amsler grid testing. Cross‐polarizing lenses enhance yield. Arch Ophthalmol 1986104520–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wolfe K A, Sadun A A. Threshold Amsler grid testing in diabetic retinopathy. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 1991229219–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mutlukan E. Red dots visual field test with blue on yellow & blue on red macula test grid. Eye 200520506–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yannuzzi L A. A modified Amsler grid: A self‐assessment test for patients with macular disease. Ophthalmology 198289157–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Preferential Hyperacuity Perimeter Research Group Results of a multicenter clinical trial to evaluate the preferential hyperacuity perimeter for detection of age‐related macular degeneration. Retina 200525296–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alster Y, Bressler N M, Bressler S B.et al Preferential Hyperacuity Perimeter (PreView PHP) for detecting choroidal neovascularization study. Ophthalmology 20051121758–1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Office of National Statistics Living in Britain: Results from the 2001 General Household Survey. London: The Stationery Office, 2002

- 36.Plummer D J, Azen S P, Freeman W R. Scanning laser entoptic perimetry for the screening of macular and peripheral retinal disease. Archives of Ophthalmology 20001181205–1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Freeman W R, El‐Bradey M, Plummer D J. Scanning laser entoptic perimetry for the detection of age‐related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol 20041221647–1651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Trauzettel‐Klosinski S, Biermann P, Hahn G.et al Assessment of parafoveal function in maculopathy: a comparison between the Macular Mapping Test and kinetic Manual Perimetry. Grafe's Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2003241988–995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]