Anorexia nervosa has the highest mortality of any psychiatric disorder.1 It has a prevalence of about 0.3% in young women. It is more than twice as common in teenage girls, with an average age of onset of 15 years; 80-90% of patients with anorexia are female. Anorexia is the most common cause of weight loss in young women and of admission to child and adolescent hospital services. Most primary care practitioners encounter few cases of severe anorexia nervosa, but these cause immense distress and frustration in carers and professionals. We describe the clinical features of anorexia nervosa and review the current evidence on treatment and management.

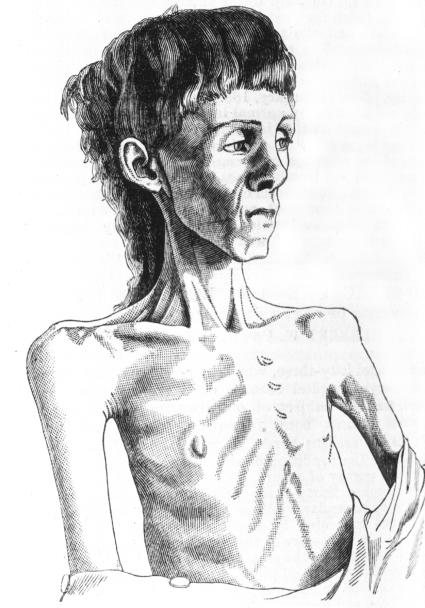

Nineteenth century drawing of young woman with anorexia nervosa

How good is the evidence for managing anorexia nervosa?

Ironically, this most lethal of psychiatric disorders is the Cinderella of research. It is hard to engage patients with anorexia for treatment, let alone research. Furthermore, the complexity of coordinated approaches used in most specialist centres may overwhelm conventional research methods.

High quality evidence on the effects of starvation on the body is available to guide physical aspects of care.2 Genetic studies, including twin and family studies,3 and more recently gene analysis, have shed some light on causes, but few randomised controlled trials of treatment exist. In contrast, many randomised controlled trials are found on the management of normal weight bulimia nervosa.4 Unfortunately, these interventions have a poor response in anorexia nervosa.

This review is based on searches in PubMed, Medline, and PsycLIT for treatment of anorexia nervosa and related eating disorders, and the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) clinical guideline.5 We found no category A evidence (at least one randomised controlled trial as part of a high quality and consistent body of literature (evidence level 1)), and only family interventions met category B criteria (well conducted clinical studies but no randomised controlled trials (evidence levels 2 and 3) or extrapolated from level I evidence). NICE uses category C recommendations (expert committee reports or clinical experience of respected authorities (evidence level 4) or extrapolation from level 2 or 3) to provide guidance where high quality formal evidence is absent.

Two Cochrane reviews cover antidepressant treatment for anorexia nervosa6 and individual psychotherapy for adults with the disorder.7 The reviews are based on only seven and six small studies, respectively, all of which had major methodological limitations. A further electronic and hand search of papers published more recently is supplemented by work in press, conference presentations, and some personal communications with the relatively small group of international experts in the field.

What are the hallmarks of anorexia nervosa?

The core psychological feature of anorexia nervosa is the extreme overvaluation of shape and weight. People with anorexia also have the physical capacity to tolerate extreme self imposed weight loss. Food restriction is only one aspect of the practices used to lose weight. Many people with anorexia use overexercise and overactivity to burn calories. They often choose to stand rather than sit; generate opportunities to be physically active; and are drawn to sport, athletics, and dance. Purging practices include self induced vomiting, together with misuse of laxatives, diuretics, and “slimming medicines.” Patients may also practise “body checking,” which involves repeated weighing, measuring, mirror gazing, and other obsessive behaviour to reassure themselves that they are still thin (box 1).

Box 1 ICD-10 (international classification of diseases, 10th revision) criteria for anorexia nervosa8

All five criteria must be met for a definite diagnosis to be made

Body weight is maintained at least 15% below that expected (either lost or never achieved) or body-mass index is 17.5 or less. Prepubertal patients may fail to gain the expected amount of weight during the prepubertal growth spurt

Weight loss is self induced by avoiding “fattening foods” together with self induced vomiting, purging, excessive exercising, or using appetite suppressants or diuretics (or both)

Body image is distorted in the form of a specific psychopathology whereby a dread of fatness persists as an intrusive, overvalued idea and the patient imposes a low weight threshold on himself or herself

A widespread endocrine disorder involving the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis is manifest in women as amenorrhoea and in men as a loss of sexual interest and potency (except for the persistence of vaginal bleeds in women who are taking replacement hormonal therapy, usually the contraceptive pill). Concentrations of growth hormone and cortisol may be raised, and changes in the peripheral metabolism of thyroid hormone and abnormalities of insulin secretion may also be seen

If onset is before puberty, the sequence of pubertal events will be delayed or even arrested (growth will cease; in girls the breasts will not develop and primary amenorrhoea will be present; in boys the genitals will remain juvenile). After recovery, puberty will often complete normally, but the menarche will be late

What causes anorexia nervosa?

Anorexia has no single cause. it seems that a genetic predisposition is necessary but not sufficient for development of the disorder. Twin and family studies,3 brain scans of affected and unaffected family members, and a current multicentre gene analysis support observations that anorexia is found in families with obsessive, perfectionist, and competitive traits, and possibly also autistic spectrum traits.

Anorexia nervosa is precipitated as a coping mechanism against, for instance, developmental challenges, transitions, family conflicts, and academic pressures. Sexual abuse may precipitate anorexia but not more commonly than it would trigger other psychiatric disorders. The onset of puberty and adolescence are particularly common precipitants, but anorexia is also found without apparent precipitants in otherwise well functioning families.

How is anorexia nervosa diagnosed and assessed?

The diagnosis is usually suspected by family, friends, and in younger patients school before a doctor becomes involved. When weight loss is well concealed, presenting features may include depression, obsessive behaviour, infertility, or amenorrhoea. Alternatively, weight loss may be thought to be secondary to allergies or other physical conditions.

A positive diagnosis of psychologically driven weight loss can be made in most patients, without the need for a battery of complex investigations to reach a diagnosis of exclusion. Basic medical investigations, blood tests, electrocardiography, weighing, and measuring the patient provide an opportunity for the patient to return (to discuss the results) and can uncover psychological problems.

If the patient refuses to be weighed it is worth persisting gently and exploring their fears. Doctors should not collude with the illness, but should advise against harmful behaviours such as running marathons, skiing, or undergoing in vitro fertilisation when at low weight.

It falls to primary care to recognise and manage relapses as well as first episodes of the illness, and to support patients and families in appropriate use of services. General practitioners may need support from a specialist in eating disorders, and early referral for more detailed assessment and advice gives patients the message that their illness is of genuine concern.

Summary points

Anorexia nervosa has the highest rate of mortality of any psychiatric disorder

It is best to make a positive diagnosis of psychologically driven weight loss, rather than reach a diagnosis by exclusion

Short term structured treatments—such as cognitive behaviour therapy—are not effective, and longer term therapies that incorporate motivational enhancement techniques are recommended

Focused family work is effective in adolescents and young adults; counselling can involve the family as a whole or the patient and their family can be treated separately

To date, no effective drugs are available to treat anorexia

How is serious physical risk managed?

The level of physical risk should be assessed at diagnosis. No safe cut off weight or body mass index exists. Survival analyses show that death is unusual where low weight is maintained purely by starvation.9 Death is more likely if the patient's weight fluctuates rapidly than if it is stable, even if the body mass index is below 12. Risk is also increased if the patient frequently purges or misuses substances.

Compulsory treatment for anorexia nervosa is clearly indicated by mental health legislation in acute emergencies where the patient is unable to accept treatment.10 In most countries this means detention in hospital. Legal responsibility becomes less clear once the immediate danger of death or irreversible deterioration has passed. Many centres invoke longer detention orders to continue compulsory refeeding to a healthier weight. Without this, the risk of repeated cycles of detention and relapse exists. In practice, patients in extremis can often be treated with their consent. Voluntary treatment is more likely when the clinician is experienced at managing anorexia and can confidently assess and tolerate fairly high levels of risk in the interests of collaborative therapeutic relationships, rather than coerce patients. Even legal measures of compulsion may be used in a helpful therapeutic way, though, and should not be avoided at all costs.

The best place to admit patients with life threatening anorexia is not always obvious. An acute medical ward—especially one that specialises in endocrinology, gastroenterology, or diabetes—is usually better than a general psychiatric ward. Some non-specialist medical wards have nurse specialists, who are experienced in managing patients with eating disorders. These nurses can help translate recommendations into practice and “troubleshoot” for the furtive compulsions of anorexia.

What is the currently accepted best management?

Anorexia takes an average of five or six years from diagnosis to recovery. Up to 30% of patients do not recover.11 12 This makes meaningful follow-up of interventions crucial but difficult. Coercive approaches may result in impressive short term weight gain but make patients more likely to identify with and cling on to the behaviour associated with anorexia.

Overall prognosis for patients with eating disorders is independent of whether treatment is received or not.13 Discredited behavioural regimens for anorexia involved incarceration in hospital, with removal of all “privileges” (visitors, television, independent use of bathroom), which were given back as a reward for weight gain.

Hospital admission is still strongly correlated with poor outcome.14 Long term prognosis is worse for patients compulsorily detained in an inpatient facility than for those treated voluntarily in the same unit, with more deaths in the first group.10 The use of brief hospital admissions to acute medical wards at times of life threatening crisis or after overdose may be associated with lower mortality.9 12

How is weight gain achieved?

In countries where all treatment is given in hospital, refeeding is an early intervention. Subsequent treatment helps patients tolerate, maintain, or regain normal weight. This may also be the preferred approach for children and young adolescents, where long periods at low weight are detrimental to growth and development. Hospital refeeding needs physiological fine tuning and may expose the patient to iatrogenic complications such as infections, the sequelae of passing tubes, and the effects of being exposed to a “proanorexia” culture (by mixing with other patients who have anorexia).

A second approach temporarily accepts low weight, if weight is stable and regularly monitored, while patients or their families take responsibility for refeeding. It is helpful to provide dietetic expertise separately from psychotherapy. One study found that unsupported dietetic advice without parallel interventions had a 100% dropout rate.15 Weight gain is slower with this second approach, but it is more likely to be maintained. This approach avoids many iatrogenic risks. However, clinicians still need access to medical wards for physical emergencies.

What is the role of psychotherapy?

Short term structured treatments such as cognitive behaviour therapy and interpersonal psychotherapy, which are effective in other eating disorders, have not helped so far in patients with anorexia. One report found no difference in outcome between behaviour therapy and cognitive therapy.16 The preliminary results of a New Zealand study of cognitive behaviour therapy and interpersonal psychotherapy compared with usual treatment were disappointing.17 A cognitive behaviour therapy based “transdiagnostic” treatment for all eating disorders, including cases of anorexia where body mass index is above 15, has shown promise however.18

Expert consensus favours long term, wide ranging, complex treatments using psychodynamic understanding, systemic principles, and techniques borrowed from motivational enhancement therapy and dialectical behavioural therapy (box 2). These treatments should be delivered in various settings that cater for the level of intensity and degree of medical monitoring and care needed. The coordinated working of a wide range of medical and psychiatric services that do not usually work together will be needed. Because of the age group affected, and the time span involved, patients' care often undergoes many transitions. These are peak times for relapse and decompensation.

Box 2 Psychotherapies available for managing anorexia nervosa

Individual therapy

Structured individual treatments are usually offered as a weekly one hour session with a therapist trained in the management of eating disorders and in the therapy model used

Cognitive analytic therapy

This psychotherapy uses letters and diagrams to examine habitual patterns of behaviour around other people and to experiment with more flexible responses

Cognitive behaviour therapy

This psychotherapy explores feelings, educates patients about body chemistry, and challenges the automatic thoughts and assumptions behind behaviour in anorexia

Interpersonal psychotherapy

This psychotherapy maps out a person's network of relationships, selects a focus—such as role conflict, transition, or loss—and works to generate new ways to deal with distress

Motivational enhancement therapy

This psychotherapy uses interviewing techniques derived from work with substance misuse to reframe “resistance” to change as “ambivalence” about change, and to nurture and amplify healthy impulses

Dynamically informed therapies

These therapies may also result in weight gain and recovery provided the patient is aware of the risk of irreversible physical damage or death and acknowledges that certain boundaries (for example, that they must be weighed weekly, examined monthly by a doctor, and admitted to hospital if weight continues on a downward trend) are observed. The therapies involve talking, art, music, and movement

Group therapy

There is little evidence that therapy for patients with anorexia benefits from being delivered in group sessions rather than individual sessions; in fact, group therapy may even worsen the problem. However, dialectical behaviour therapy offers structured groups in parallel with individual sessions. This therapy teaches skills that help patients to tolerate distress, soothe their feelings, and manage interpersonal relationships

Family work

The term “family work” covers any intervention that harnesses the strengths of the family in tackling the patient's disorder or that tries to deal with the family's stress in the face of it. It includes family therapies, support groups, and psychoeducational input

Conjoint therapy

Evidence points to the effectiveness of the Maudsley model of family therapy and similar interventions focused on eating disorders. Whole families—or at least the parents and the patient—attend counselling sessions together, which can cause intolerable emotional stress

Separated family therapy

The patient and the parents attend separate meetings, sometimes with two different therapists. This form of therapy seems to be as effective as conjoint therapy, particularly for older patients, and involves lower levels of expressed emotion

Multifamily groups

Such groups provide a novel way of empowering parents by means of peer support and help from a therapist. Several families, including the patients, meet together for intensive sessions that often last the whole day and include eating together

Relatives' and carers' support groups

These groups range from self help meetings to highly structured sessions led by a therapist that aim to teach psychosocial and practical skills to help patients with anorexia to recover while avoiding unnecessary conflict. Most encompass at least some educational input about the nature of anorexia

Early on, especially in younger patients, motivation for treatment lies with parents, schoolteachers, or medical professionals. The guiding principle of motivational enhancement is to acknowledge and explore rather than fight the patient's ambivalence about recovery. Treatment is more effective when the therapist and the patient work together against the anorexia. Such a relationship may allow the patient to be treated without having to invoke the Mental Health Act. Motivation is not an all or nothing battle to be won before treatment can start—it must be actively engendered throughout the treatment.

TIPS FOR NON-SPECIALISTS

Recovery takes years rather than weeks or months, and patients must accept that they should attain a normal weight—refeeding alone may lead to relapse

Trends should be monitored by weighing, which needs to be managed skilfully so it does not become a battleground

No cut off weight or body mass index exists because many other factors influence risk

Substance misuse—including alcohol, deliberate overdoses, or misuse of prescribed insulin—greatly increases risk

Weight fluctuations and binge-purge methods (rather than pure restriction) increase risk

Depression, anxiety, and family arguments are probably secondary to the disorder, not underlying causes, so the anorexia should be treated first

Medication has little benefit in anorexia and the risk of dangerous side effects is high in malnourished patients

Try to involve the family—encourage calm firmness and assertive care

Family work is the only well researched intervention that has a beneficial impact.19 Family work teaches the family and patient to be aware of the perpetuating features of the disorder. Fury, anger, and fighting lead to entrenched symptoms but too much permissiveness encourages the illness by allowing it to become an accepted response to stress, or—if the family will do anything to encourage the patient to eat—a route to providing “secondary gain” from the illness. Support of carers is essential to maintain the firm but sympathetic boundaries conducive to recovery

Early studies on teenagers with relatively recent onset anorexia showed that therapy involving the whole family was superior to treating just the patient. Further studies showed that, if tolerated, sessions involving the family and patient together gave the best results in terms of the family's psychological adjustment, but that weight gain was greater when families were seen separately from the patient.19 Both types of family intervention were more effective than individual work. More recently, “multi-family groups” have been piloted.20

The Maudsley group compared individual focused dynamic therapy, dynamically informed family therapy, individual cognitive analytic therapy, and “treatment as usual” over the course of a year.21 The dynamically informed therapies—both family and individual—produced the best results. The study showed that severely ill adults with anorexia could be managed as outpatients, and it highlighted the benefits of continuity of care by one therapist and of the expertise provided. However, nothing can be concluded about the specific model of therapy provided.

What is it like to experience anorexia nervosa?

At first I believed my thoughts were normal when I looked in the mirror—you don't expect your eyes to lie. I felt such self loathing that I drastically reduced my food intake and did a lot of exercise. I felt better about myself and decided that once I'd lost a pound or two I would eat normally again. When it came to it I was too scared. It felt good to lose a couple of pounds but it became addictive. If I did a certain amount of exercise one day, the next day I had to do at least the same amount. I ended up feeling physically rubbish, but my mind said I'm a horrible person who deserves pain.

Paranoia sets in. You're convinced people think you are fat even when they say you are not. Your mind tells you they are lying, until you find you can't trust anyone. Living with anorexia is a constant battle between two evils. On one hand eating feels like an evil thing, but other people see that very belief as the evil. When I feel I really must starve or exercise I get angry with the nurses. Other times it's a relief though, because at least they take the responsibility away from me.

S, aged 17

Is drug treatment effective?

The evidence base for the use of drugs in anorexia nervosa is poor. Antidepressants are often used to treat depressive symptoms but have limited success. The well documented benefits of antidepressants in bulimia nervosa4 do not extend to anorexia, and the benefit from selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in preventing relapse after weight gain is unclear. Case reports describe the benefit of antipsychotic drugs such as olanzapine to promote weight gain. This success may be attributable to symptomatic relief of anxiety and increased appetite, rather than any effect on core pathology. Harmful effects of drugs, particularly the appearance of a long QT interval, with the risk of dangerous cardiac dysrhythmias, are more likely in patients who are malnourished and have electrolyte abnormalities.

What affects recovery and what is the prognosis?

A premature mortality rate of 20% was seen in an inpatient cohort, and a large proportion of cases took six to 12 years to resolve.11 Bingeing and vomiting at low weight greatly increase mortality compared with purely restrictive starvation. Comorbidity is associated with bleaker prognosis. More recently, full recovery has been demonstrated even after 21 years of chronic severe anorexia nervosa.12

Criteria are available for assessing recovery from anorexia nervosa.11 The capacity to undertake normal levels of exercise and activity are also important. If the patient is given renutrition and care to protect against irreversible damage during the acute illness, cardiovascular function, immune function, fertility, and bone density can all return to healthy levels. Bone recovery takes years rather than months, so patients should protect the spine and pelvis in particular against gymnastic activity too early after weight gain. Even when a person has developed the crucial motivation to tolerate weight gain and explored the possibility of living with values other than those imposed by the cult of thinness, psychological recovery is difficult as the challenges of a rekindled adolescence must be faced.

ADDITIONAL EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES

Resources for healthcare professionals

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (www.nice.org.uk)—Several guidelines are available that cover anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and atypical eating disorders

American Psychiatric Association (www.psych.org/psych_pract/treatg/pg/EatingDisorders3ePG_04-28-06.pdf)—A recently published guideline on the treatment of patients with eating disorders

The Edinburgh Anorexia Nervosa Intensive Treatment Team (www.anitt.org.uk)—This site contains a detailed clinical pathway for anorexia nervosa

Institute of Psychiatry/Maudsley Hospital (www.iop.kcl.ac.uk/)—This site has good information and downloadable PDFs on medical complications of eating disorders and is kept up to date with research development

Treasure J. Anorexia nervosa: a survival guide for families, friends and sufferers. Hove: Psychology Press, 1997

Resources for patients and carers

Beating Eating Disorders (www.edauk.com)—The Eating Disorders Association site has good information about the eating disorders network in the United Kingdom, resource lists, and details of local self help and support groups

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (www.nice.org.uk)—This site also contains a patient and carer version of the NICE guidelines

Bloomfield S. Eating disorders: helping your child recover. Norwich: Eating Disorders Association, 2006

Bryant-Waugh R, Lask B. Eating disorders: a parents' guide. Revised ed. Hove: Brunner-Routledge, 2004

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Hoek HW. Incidence, prevalence and mortality of anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2006;19:389-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keys A, Brozek J, Henschel A, Mickelsen O, Taylor HL. The biology of human starvation Vols 1, 2. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1950

- 3.Bulik CM, Sullivan PF, Wade T, Kendler KS. Twin studies of eating disorders: a review. Int J Eating Disord 2000;27:1-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bacaltchuk J, Hay P, Trefiglio R. Antidepressants versus psychological treatments and their combination for people with bulimia nervosa. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;(1):CD003385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. Eating disorders: core interventions in the treatment and management of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and related eating disorders National Clinical Practice Guideline no CG9. London: British Psychological Society and Gaskell, 2004 [PubMed]

- 6.Claudino AM, Hay P, Lima MS, Bacaltchuk J, Schmidt U, Treasure J. Antidepressants for anorexia nervosa. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;(1):CD004365. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Hay P, Bacaltchuk J, Claudino AM, Ben-Tovim D, Yong PY. Individual psychotherapy in the outpatient treatment of adults with anorexia nervosa. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003;(4):CD003909. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.WHO. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems, 10th revision Geneva: WHO, 1992

- 9.Herzog DB, Greenwood DN, Dorer DJ, Flores AT, Ekeblad ER, Richards A, et al. Mortality in eating disorders: a descriptive study. Int J Eating Disord 2000;28:20-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramsay R, Ward A, Treasure J, Russell GF. Compulsory treatment in anorexia nervosa: short-term benefits and long-term mortality. Br J Psychiatry 1999;175:147-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Theander S. Outcome and prognosis in anorexia nervosa and bulimia. Some results of previous investigations compared with those of a Swedish long-term study. J Psychiatr Res 1985;19:493-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lowe B, Zipfel S, Buchholz C, Dupont Y, Reas DL, Herzog W. Long-term outcome of anorexia nervosa in a prospective 21-year follow-up study. Psychol Med 2001;31:881-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gowers SG, Weetman J, Shore S, Hossain F, Elvins R. Impact of hospitalization on the outcome of anorexia nervosa. Br J Psychiatry 2000;176:138-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ben-Tovim DI, Walker K, Gilchrist P, Freeman R, Kalucy R, Esterman A. Outcome in patients with eating disorders: a 5-year study. Lancet 2001;357:1254-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Serfaty MA. Cognitive therapy versus dietary counselling in the outpatient treatment of anorexia nervosa: effects of the treatment phase. Eur Eating Disord Rev 1999;7:334-50. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Channon S, De Silva WP, Hemsley D, Perkins R. A controlled trial of cognitive-behavioural and behavioural treatment of anorexia nervosa. Behav Res Ther 1989;27:529-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McIntosh VVW, Jordan J, Carter FA, Luty SE, McKenzie JM, Bulik CM, et al. Three psychotherapies for anorexia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162:741-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fairburn CG. Evidence-based treatment of anorexia nervosa. Int J Eating Disord 2005;37(suppl 1):S26-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eisler I, Dare C, Hodes M, Russell G, Dodge E, Le Grange D. Family therapy for anorexia nervosa in adolescents: the results of a controlled comparison of two family interventions. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2000;41:727-36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dare C, Eisler I. A multi-family group day treatment programme for adolescent eating disorder. Eur Eating Disord Rev 2002;8:4-18. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dare C, Eisler I, Russell GFM, Treasure J, Dodge L. Psychological therapies for adults with anorexia nervosa: randomised controlled trial of out-patient treatments. Br J Psychiatry 2001;178:216-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]