Abstract

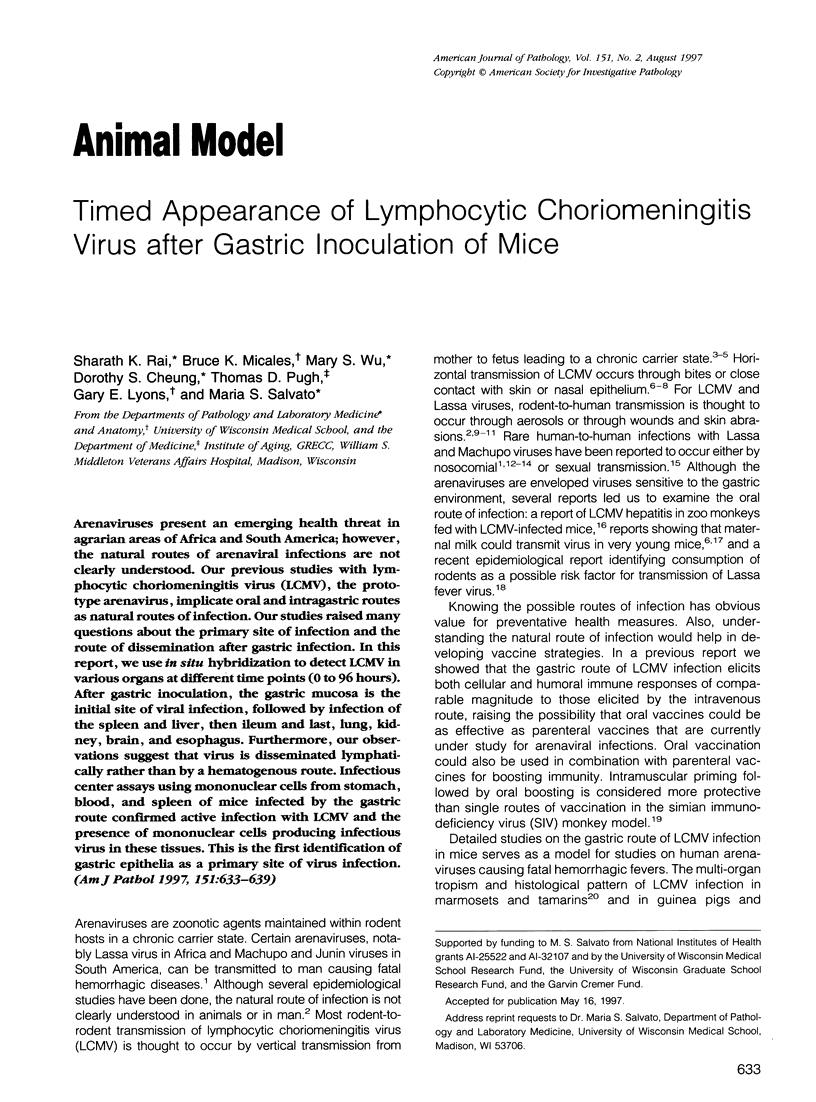

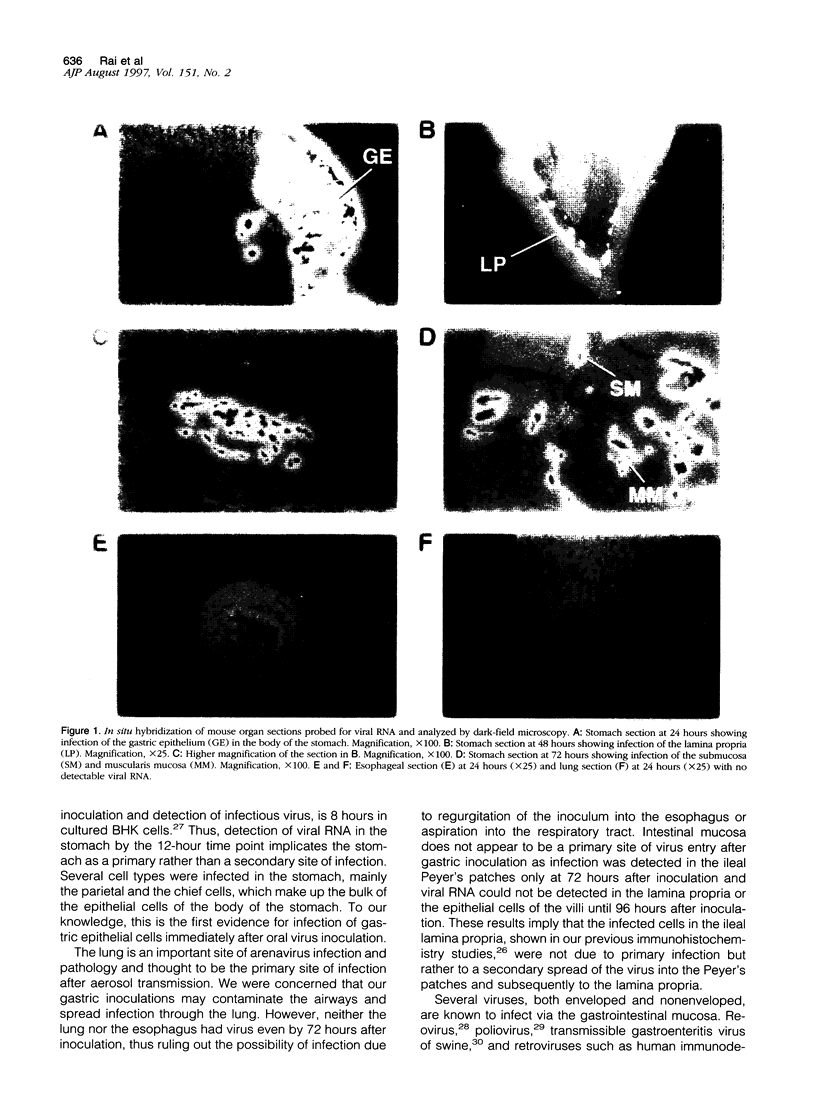

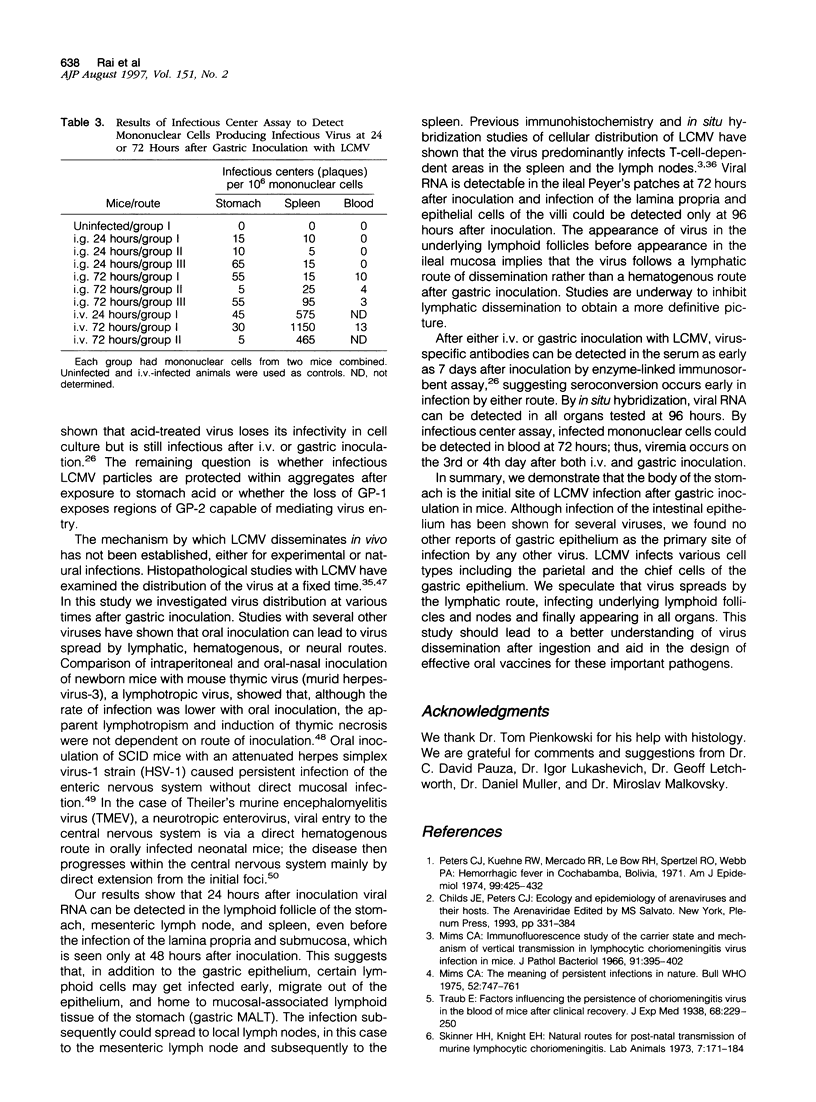

Arenaviruses present an emerging health threat in agrarian areas of Africa and South America; however, the natural routes of arenaviral infections are not clearly understood. Our previous studies with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV), the prototype arenavirus, implicate oral and intragastric routes as natural routes of infection. Our studies raised many questions about the primary site of infection and the route of dissemination after gastric infection. In this report, we use in situ hybridization to detect LCMV in various organs at different time points (0 to 96 hours). After gastric inoculation, the gastric mucosa is the initial site of viral infection, followed by infection of the spleen and liver, then ileum and last, lung, kidney, brain, and esophagus. Furthermore, our observations suggest that virus is disseminated lymphatically rather than by a hematogenous route. Infectious center assays using mononuclear cells from stomach, blood, and spleen of mice infected by the gastric route confirmed active infection with LCMV and the presence of mononuclear cells producing infectious virus in these tissues. This is the first identification of gastric epithelia as a primary site of virus infection.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Ahmed R., Salmi A., Butler L. D., Chiller J. M., Oldstone M. B. Selection of genetic variants of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus in spleens of persistently infected mice. Role in suppression of cytotoxic T lymphocyte response and viral persistence. J Exp Med. 1984 Aug 1;160(2):521–540. doi: 10.1084/jem.160.2.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amerongen H. M., Weltzin R., Farnet C. M., Michetti P., Haseltine W. A., Neutra M. R. Transepithelial transport of HIV-1 by intestinal M cells: a mechanism for transmission of AIDS. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1991;4(8):760–765. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baba T. W., Trichel A. M., An L., Liska V., Martin L. N., Murphey-Corb M., Ruprecht R. M. Infection and AIDS in adult macaques after nontraumatic oral exposure to cell-free SIV. Science. 1996 Jun 7;272(5267):1486–1489. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5267.1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blount P., Elder J., Lipkin W. I., Southern P. J., Buchmeier M. J., Oldstone M. B. Dissecting the molecular anatomy of the nervous system: analysis of RNA and protein expression in whole body sections of laboratory animals. Brain Res. 1986 Sep 24;382(2):257–265. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)91335-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodkin D. K., Nibert M. L., Fields B. N. Proteolytic digestion of reovirus in the intestinal lumens of neonatal mice. J Virol. 1989 Nov;63(11):4676–4681. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.11.4676-4681.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrow P., Oldstone M. B. Characterization of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus-binding protein(s): a candidate cellular receptor for the virus. J Virol. 1992 Dec;66(12):7270–7281. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.12.7270-7281.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrow P., Oldstone M. B. Mechanism of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus entry into cells. Virology. 1994 Jan;198(1):1–9. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruns M., Lehmann-Grube F. Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. VII. Structural alterations of the virion by treatment with proteolytic enzymes without loss of infectivity. J Gen Virol. 1984 Aug;65(Pt 8):1431–1435. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-65-8-1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchmeier M. J., Elder J. H., Oldstone M. B. Protein structure of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus: identification of the virus structural and cell associated polypeptides. Virology. 1978 Aug;89(1):133–145. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(78)90047-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey D. E., Kemp G. E., White H. A., Pinneo L., Addy R. F., Fom A. L., Stroh G., Casals J., Henderson B. E. Lassa fever. Epidemiological aspects of the 1970 epidemic, Jos, Nigeria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1972;66(3):402–408. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(72)90271-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clague M. J., Schoch C., Zech L., Blumenthal R. Gating kinetics of pH-activated membrane fusion of vesicular stomatitis virus with cells: stopped-flow measurements by dequenching of octadecylrhodamine fluorescence. Biochemistry. 1990 Feb 6;29(5):1303–1308. doi: 10.1021/bi00457a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DANES L., BENDA R., FUCHSOVA M. EXPERIMENT'ALN'I INHALA CN'I N'AKAZA OPIC DRUHU MACACUS CYNOMOLGUS A MACACUS RHESUS VIREM LYMFOCIT'ARN'I CHORIOMENINGITIDY (KMENEM WE) Bratisl Lek Listy. 1963;2:71–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delmas B., Gelfi J., L'Haridon R., Vogel L. K., Sjöström H., Norén O., Laude H. Aminopeptidase N is a major receptor for the entero-pathogenic coronavirus TGEV. Nature. 1992 Jun 4;357(6377):417–420. doi: 10.1038/357417a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Simone C., Zandonatti M. A., Buchmeier M. J. Acidic pH triggers LCMV membrane fusion activity and conformational change in the glycoprotein spike. Virology. 1994 Feb;198(2):455–465. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle M. V., Oldstone M. B. Interactions between viruses and lymphocytes. I. In vivo replication of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus in mononuclear cells during both chronic and acute viral infections. J Immunol. 1978 Oct;121(4):1262–1269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazakerley J. K., Southern P., Bloom F., Buchmeier M. J. High resolution in situ hybridization to determine the cellular distribution of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus RNA in the tissues of persistently infected mice: relevance to arenavirus disease and mechanisms of viral persistence. J Gen Virol. 1991 Jul;72(Pt 7):1611–1625. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-7-1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gesser R. M., Valyi-Nagy T., Fraser N. W., Altschuler S. M. Oral inoculation of SCID mice with an attenuated herpes simplex virus-1 strain causes persistent enteric nervous system infection and gastric ulcers without direct mucosal infection. Lab Invest. 1995 Dec;73(6):880–889. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha-Lee Y. M., Dillon K., Kosaras B., Sidman R., Revell P., Fujinami R., Chow M. Mode of spread to and within the central nervous system after oral infection of neonatal mice with the DA strain of Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus. J Virol. 1995 Nov;69(11):7354–7361. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.7354-7361.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotchin J. Virus, cell surface, and self: lymphocytic choriomeningitis of mice. Am J Clin Pathol. 1971 Sep;56(3):333–349. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/56.3.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaax N. K., Davis K. J., Geisbert T. J., Vogel P., Jaax G. P., Topper M., Jahrling P. B. Lethal experimental infection of rhesus monkeys with Ebola-Zaire (Mayinga) virus by the oral and conjunctival route of exposure. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1996 Feb;120(2):140–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann-Grube F. Portraits of viruses: arenaviruses. Intervirology. 1984;22(3):121–145. doi: 10.1159/000149543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons G. E., Ontell M., Cox R., Sassoon D., Buckingham M. The expression of myosin genes in developing skeletal muscle in the mouse embryo. J Cell Biol. 1990 Oct;111(4):1465–1476. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.4.1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx P. A., Compans R. W., Gettie A., Staas J. K., Gilley R. M., Mulligan M. J., Yamshchikov G. V., Chen D., Eldridge J. H. Protection against vaginal SIV transmission with microencapsulated vaccine. Science. 1993 May 28;260(5112):1323–1327. doi: 10.1126/science.8493576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton P. J. Viruses that multiply in the gut and cause endemic and epidemic gastroenteritis. Clin Diagn Virol. 1996 Aug;6(2-3):93–101. doi: 10.1016/0928-0197(96)00231-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mims C. A. Immunofluorescence study of the carrier state and mechanism of vertical transmission in lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infection in mice. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1966 Apr;91(2):395–402. doi: 10.1002/path.1700910214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mims C. A. The meaning of persistent infections in nature. Bull World Health Organ. 1975;52(4-6):747–751. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monath T. P. Lassa fever: review of epidemiology and epizootiology. Bull World Health Organ. 1975;52(4-6):577–592. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montali R. J., Connolly B. M., Armstrong D. L., Scanga C. A., Holmes K. V. Pathology and immunohistochemistry of callitrichid hepatitis, an emerging disease of captive New World primates caused by lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. Am J Pathol. 1995 Nov;147(5):1441–1449. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montali R. J., Scanga C. A., Pernikoff D., Wessner D. R., Ward R., Holmes K. V. A common-source outbreak of callitrichid hepatitis in captive tamarins and marmosets. J Infect Dis. 1993 Apr;167(4):946–950. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.4.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse S. S. Thymic necrosis following oral inoculation of mouse thymic virus. Lab Anim Sci. 1989 Nov;39(6):571–574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neutra M. R., Kraehenbuhl J. P. Transepithelial transport and mucosal defence I: the role of M cells. Trends Cell Biol. 1992 May;2(5):134–138. doi: 10.1016/0962-8924(92)90099-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaum O., Lapidot M., Loyter A. Reconstitution of functional influenza virus envelopes and fusion with membranes and liposomes lacking virus receptors. J Virol. 1987 Jul;61(7):2245–2252. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.7.2245-2252.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaum O., Rott R., Loyter A. Fusion of influenza virus particles with liposomes: requirement for cholesterol and virus receptors to allow fusion with and lysis of neutral but not of negatively charged liposomes. J Gen Virol. 1992 Nov;73(Pt 11):2831–2837. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-11-2831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters C. J., Jahrling P. B., Liu C. T., Kenyon R. H., McKee K. T., Jr, Barrera Oro J. G. Experimental studies of arenaviral hemorrhagic fevers. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1987;134:5–68. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-71726-0_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters C. J., Kuehne R. W., Mercado R. R., Le Bow R. H., Spertzel R. O., Webb P. A. Hemorrhagic fever in Cochabamba, Bolivia, 1971. Am J Epidemiol. 1974 Jun;99(6):425–433. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a121631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rai S. K., Cheung D. S., Wu M. S., Warner T. F., Salvato M. S. Murine infection with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus following gastric inoculation. J Virol. 1996 Oct;70(10):7213–7218. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.10.7213-7218.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvato M. S., Shimomaye E. M. The completed sequence of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus reveals a unique RNA structure and a gene for a zinc finger protein. Virology. 1989 Nov;173(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90216-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siciński P., Rowiński J., Warchoł J. B., Jarzabek Z., Gut W., Szczygieł B., Bielecki K., Koch G. Poliovirus type 1 enters the human host through intestinal M cells. Gastroenterology. 1990 Jan;98(1):56–58. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)91290-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner H. H., Knight E. H. Epidermal tissue as a primary site of replication of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus in small experimental hosts. J Hyg (Lond) 1979 Feb;82(1):21–30. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400025432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner H. H., Knight E. H. Natural routes for post-natal transmission of murine lymphocytic choriomeningitis. Lab Anim. 1973 May;7(2):171–184. doi: 10.1258/002367773781008597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson E. H., Larson E. W., Dominik J. W. Effect of environmental factors on aerosol-induced Lassa virus infection. J Med Virol. 1984;14(4):295–303. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890140402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ter Meulen J., Lukashevich I., Sidibe K., Inapogui A., Marx M., Dorlemann A., Yansane M. L., Koulemou K., Chang-Claude J., Schmitz H. Hunting of peridomestic rodents and consumption of their meat as possible risk factors for rodent-to-human transmission of Lassa virus in the Republic of Guinea. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1996 Dec;55(6):661–666. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1996.55.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf J. L., Rubin D. H., Finberg R., Kauffman R. S., Sharpe A. H., Trier J. S., Fields B. N. Intestinal M cells: a pathway for entry of reovirus into the host. Science. 1981 Apr 24;212(4493):471–472. doi: 10.1126/science.6259737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]