Abstract

The University of Maryland School of Pharmacy has systematically implemented professionalism assessment to establish expectations in experiential learning and to create a mechanism for holding students accountable for professionalism. The authors describe their philosophic approach to the development and implementation of these explicit criteria and also review the outcomes of applying these criteria.

In 2001, 3 professionalism criteria were developed and applied to required intermediate and advanced pharmacy practice experiences (APPEs). Students were expected to achieve 100% acceptable ratings to pass the rotations. The criteria were subsequently enhanced and by 2005 applied to all experiential courses.

Most students exhibited professional behavior; however, 9 students did not meet the established criteria. Strategies used in remediation and further professional development are discussed. The use of professionalism criteria has promoted a culture of professionalism throughout the School.

Keywords: professionalism, experiential learning, preceptor, advanced pharmacy practice experience, introductory pharmacy practice experience

INTRODUCTION

Professionalism is a continually evolving issue that must be addressed in the context of expectations and goals for pharmacists and student pharmacists. With the erosion of values and civility (beyond basic politeness, manners, and courtesy) within society at large, self-expression may manifest as unchecked impulses and irresponsible self-indulgence. Incivility plays out in traffic, retail sales transactions, and public places where people are subjected to loud cell phone conversations and rude language. Many individuals will do whatever is best for themselves, regardless of what may be best for others, for immediate gratification. Alternatively, Forni has stated that if restraint is the infusion of thinking and thoughtfulness into everything we do, then we delay gratification by choosing a behavior that will make us feel good 5 minutes from now, or next year.1 Since individuals involved with the practice of pharmacy and pharmacy education reflect the general norms of society, this erosion of civility and restraint may influence the behavior of practitioners, faculty members, and students in the profession.

In recent years, pharmacy education has responded to these changes by re-emphasizing professionalism within pharmacy education and practice. The 2000 White Paper on Student Professionalism2 identified several issues involving professionalism and described specific strategies to enhance professionalism within pharmacy education and the early years of pharmacy practice. In addition, the task force that developed this white paper has prepared an interactive “toolkit” for student pharmacists, practitioners, and faculty members to help them deal with professional issues within pharmacy academia.3 Faculty members within pharmacy education have also developed innovative ways to assess and change professional behavior.4 In addition, the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy commissioned a white paper to “provoke thought in the pharmacy academy about the critical and comprehensive need to address professionalism.”5 These efforts have stimulated colleges and schools of pharmacy, as well as pharmacy organizations, to monitor and enhance the professional development of student pharmacists and practitioners.

At the University of Maryland School of Pharmacy, faculty members, students, and administrators have tried to incorporate many of these suggested strategies into our academic enterprise. Examples include:

conducting faculty, student, and staff civility training;

developing and implementing explicit standards of conduct during student extracurricular activities;

establishing standards and expectations for use of technology (ie, e-mail, computer use in classroom, refraining from/avoiding plagiarism, etc) as part of student professional development;

enhancing communication to faculty members and students regarding professionalism and consequences of not meeting expectations;

developing innovative remediation approaches for cases brought before the disciplinary committee; and

developing a continuum of expectations and accountability for major components of the curriculum from early practice laboratory experiences through advanced experiential learning.

The School also implemented a white coat ceremony several years ago for first-professional year pharmacy students. The School values this tradition and its symbolic message for both its students and faculty members but realizes that more needs to be done. It is much easier for schools to implement rituals, such as a white coat ceremony, than to systematically create expectations and accountability for professionalism throughout the entire educational experience.6

This paper focuses on the School's attempt to address professionalism competency throughout its experiential learning program and the challenges faced. For example, students experience challenges in the transition from being a typical college student (with a different set of expectations) to a student in a professional program. Professional issues reveal themselves not only in the classroom, but also during introductory pharmacy practice experiences (IPPEs) and APPEs. Several preceptors have indicated that they are concerned about students' unprofessional behavior during IPPEs and APPEs. Issues of timeliness, communications at the practice site, and commitment in terms of “work ethic” were problems frequently voiced by preceptors. Based on these behaviors, School faculty members, administrators, and preceptors felt compelled to articulate expectations to students related to professionalism and to hold students accountable for their nonprofessional behavior during experiential learning rotations.

DESIGN

The Experiential Learning Program (ELP) at the University of Maryland School of Pharmacy is a comprehensive curriculum of introductory through advanced pharmacy practice experiences, which occur throughout the 4 professional years. Students complete at least 16 experiential rotations consisting of 25 required credits and at least 8 elective credits. The length of the IPPEs and APPEs ranges from 1 day to 12 weeks depending on the specific course and designated rotation objectives, and total approximately 1600 hours currently. The Maryland Board of Pharmacy accepts completion of the ELP toward licensure and does not require internship hours for Maryland graduates.

Prior to 2001, students completing IPPEs and APPEs were evaluated on professional behavior using a 5-point Likert scale for punctuality, active participation, appropriate interaction, and appropriate attire. However, the terms were not defined and the criteria were not specific. An acceptable rating was defined only as “usually meeting the performance standard.” A low rating for behavior would not prevent a student from passing the course if scores in other course elements were high enough to offset the deficiency. Professionalism was a factor, but not a determining factor.

Faculty decided to establish clear professionalism expectations in experiential learning and to create a mechanism for holding students accountable for professionalism. In order to accomplish these 2 goals, criteria needed to be developed and implemented systematically and incrementally.

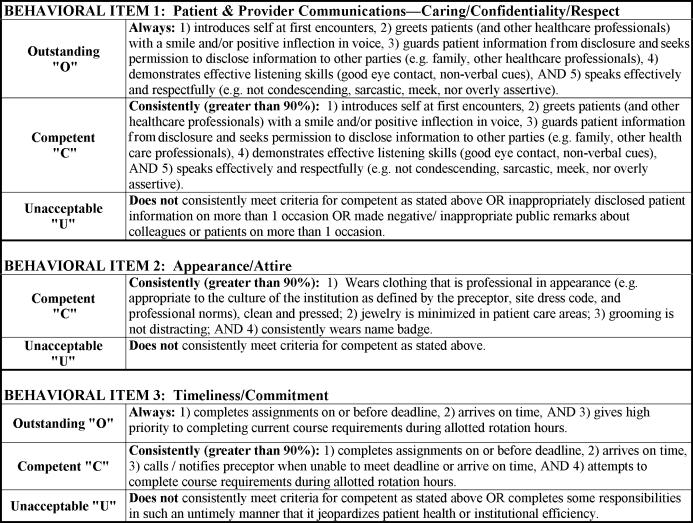

During a major course revision in early 2001, the course managers for the students' first full-time, 4-week experiential rotations following the second-professional year (courses PHPC 570 and PHPC 571) developed and incorporated 3 specific professional behavioral criteria. These 3 major professional behaviors included patient and provider communications (caring, confidentiality, respect), appearance and attire, and timeliness and commitment (Figure 1). Appearance and attire were challenging given current fashions, body piercing, and tattoos. Wording was carefully chosen to be both culturally sensitive and consistent with expectations for pharmacy practice laboratory activities where professional norms are taught. There is leeway to allow for the variety of practice settings with the wording “appropriate to the culture of the institution as defined by the preceptor, site dress code and professional norms.” Students were required to achieve outstanding or competent ratings on all 3 by the end of the rotation in order to pass the rotation. In other words, a student could fail based solely upon unsatisfactory professional behavior even if other course objectives had been completed satisfactorily. Students were oriented to the course, including the new criteria, and encouraged to seek course managers' assistance for difficult issues such as personality conflicts or harassment of any kind. The new criteria were mailed or e-mailed to preceptors prior to the 2001-2002 rotation cycle, and they were asked to provide real time, face-to-face evaluations at both the midpoint and end of the experiences.

Figure 1.

Initial professionalism criteria implemented by the University of Maryland School of Pharmacy (2001).

RESULTS

Out of 167 intermediate student experiential rotations for PHPC 570 and PHPC 571 during the summer of 2001, only 1 student did not pass based on behavioral elements. The student was counseled and allowed to repeat the course, which he/she then completed satisfactorily. Previously, unsatisfactory professional behavior alone, unless it had been a major site policy infraction, would not have prevented the student from passing and would not have resulted in remediation.

Concurrently, these criteria were adopted for the required advanced practice pharmaceutical care APPEs which were conducted every 4 weeks from the end of May 2001 until February 2002. From 371 student APPEs, 1 student did not meet the professionalism behavioral criteria which resulted in course failure and academic suspension.

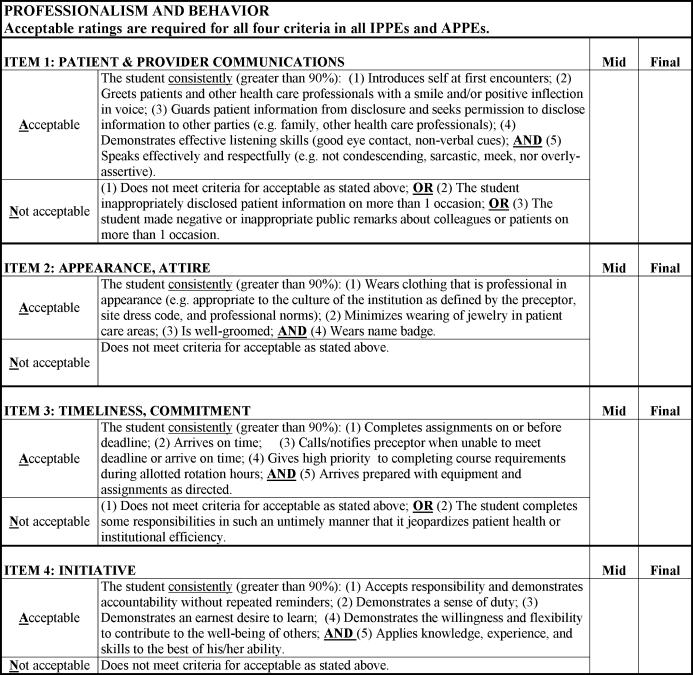

By spring 2004, with continued preceptor input, the Experiential Learning Committee (ELC), which was composed of all course managers for required experiential learning courses, identified a shortcoming in the professionalism behavioral criteria in the area of student preparedness on IPPEs and APPEs. Preceptors had noted that students were coming to sites unprepared, and despite preceptors' directions, were not following through on assignments. By August, a criterion for assessing/evaluating initiative was developed and instituted (Figure 2.) Also, the “unacceptable” rating was changed to “not acceptable” and professionalism criteria were changed to 2 ratings: acceptable or not acceptable. Because students are still learning and developing as professionals, the acceptable level was set at greater than 90%, rather than expecting perfection at 100%. With the support of the Curriculum Committee, in fall 2004, the ELC applied the professionalism criteria to all required experiential courses including the 3 IPPEs during the first-professional year, for a total of 25 of 33 experiential academic credits. Throughout the 2004-2005 academic year, the ELC assisted faculty members in creating and implementing criteria-based assessments, including professionalism, for all experiential learning courses, with full implementation in the 2005-2006 cycle.

Figure 2.

Initiative added to the University of Maryland School of Pharmacy's professionalism criteria (2004).

The experiential course failures are considered by the designated school committee in the same manner and by the same procedures as didactic course failures. The consequences range from probation until the failure is removed, to dismissal. Students may send a letter to the Committee or appear in person to respond to the failure rating, and they may appeal the Committee's decision. When students are allowed to repeat the rotation, the course manager matches them with another site and a different preceptor. Not all cases result in requiring the student to repeat a rotation. Other innovative remediation approaches have included a student professionalism presentation to the incoming class, an intensive project with a preceptor who evaluated the project results and all aspects of professionalism, and a professionalism contract between a student and a faculty remediator. The contract centered on professionalism development, the history of pharmacy professionals in Maryland, and application to the profession, and required the student to

Reflect on background readings such as the white paper on pharmacy student professionalism2;

Identify current school initiatives to promote professionalism;

Offer suggestions for improvement on these initiatives from the viewpoints of students, staff members, and faculty members;

Explore the B. Olive Cole Museum at the Maryland Pharmacists Association (MPhA) which was founded in 1882,

Identify past MPhA Speakers of the House of Delegates using the archives,

Attend a meeting of a pharmacy organization with the faculty remediator, and

Sign the contract, including the expectations to demonstrate professionalism (existing criteria), to meet regularly with the faculty remediator, and to reflect on experiences prior to speaking with the Associate Dean for Student Affairs, Director of Student Services, and Director of Experiential Learning before the committee follow-up meeting.

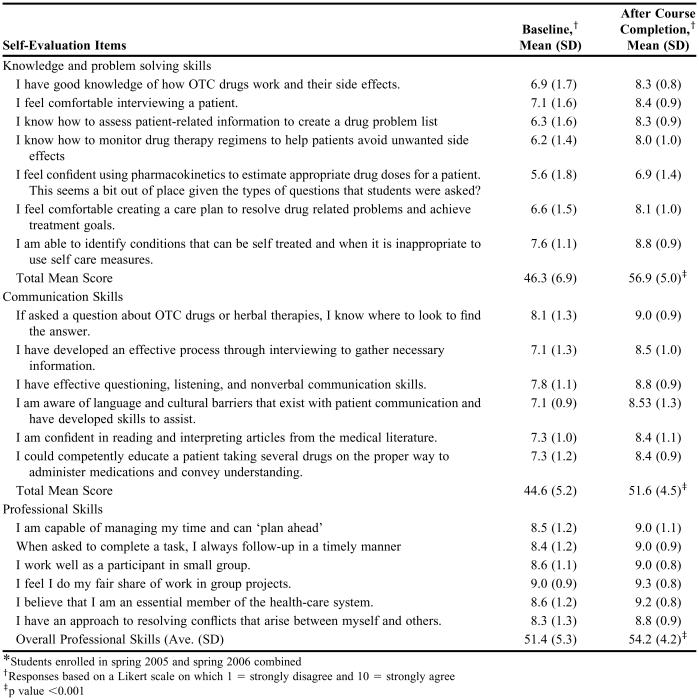

Since 2001, nine students have failed a rotation solely for unprofessional behavior; no more than 2 instances occurred in any given year out of the 1,920 APPEs that students completed. Other failures resulted due to professional issues combined with academic issues or unreported health concerns. From a review of committee minutes, in 2003-2003, there were 3 combined issues and 15 academic issues. In 2003-2004, there were no combined issues and 20 solely academic issues. During 2004-2005, the committee heard cases for 4 combined issues and 25 academic issues. Through the 2005-2006 academic year, 4 combined issues and 18 academic cases were deliberated. While the number of professionalism failures is very small for classes of approximately 120 students who complete at least 16 IPPEs and APPEs prior to graduation, the issues of lack of timeliness and commitment in particular were deemed serious. These issues affected workflow and other individuals at the sites, and they were not resolved by the conclusion of the experiential rotations, despite midpoint assessments. In discussions with course managers about such problems, preceptors have admitted they were reluctant to fail students. But when asked if they would “tolerate such repeated behavior and work ethic in an employee or colleague,” they applied the criteria and submitted the not acceptable rating the student had earned. To date, 7 of the students who received “not acceptable” ratings have since graduated and 2 remain in the program. The results are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Outcome of Professionalism Failures Among Students Completing Introductory and Advanced Pharmacy Practice Experiences (N = 5094) at the University of Maryland School of Pharmacy After Implementation of Criteria for Professionalism Assessment (2001-2006)

DISCUSSION

Standardizing student assessment among preceptors, especially assessment of professional behaviors, attitudes, and values within the affective domain, is an ongoing challenge for experiential learning faculty members.7 Once specific professional behavior criteria are defined, they must be supported throughout the curriculum as students learn and practice what is expected once they leave the didactic setting.

The University of Maryland School of Pharmacy is committed to professionalism as an integral part of the School by setting professional behavior expectations for the classroom and implementing professionalism criteria in experiential courses. The School has been able to operationalize these professionalism criteria by establishing processes that have demonstrated to the educational community that professionalism is a serious issue at the institution.

Preceptors have an essential role in the assessment process. To prepare them, the School has provided basic training modules in CD-ROM format on roles and responsibilities and assessment as learning, including application of the professionalism criteria. Preceptors must clearly articulate site-specific professional expectations and demonstrate these expected behaviors. Midpoint evaluation criteria must be applied fairly and communicated to students in person to provide appropriate feedback for areas in need of improvement. By performing midpoint student assessments, in addition to the final evaluations, preceptors are usually able to ensure students' success, which is the goal.

Likewise, preceptors must exhibit the same professionalism that is expected of students. In order to encourage preceptors to meet this expectation, starting with the 2006-2007 rotation cycle, ELP transitioned from a basic paper-based preceptor evaluation to a more complete and standardized web-based Student Evaluation of Self, Preceptor, and Site program. In addition to responding to questions about his or her preceptor's teaching competencies, each student rates the preceptor as a professional role model. This information is summarized without individual student identifiers and provided annually to preceptors as formative feedback. Course managers also monitor evaluations throughout the year and intervene as necessary once they have collected complete and balanced information, including the review of the preceptor's previous evaluations. ELP course managers report ongoing results following each experiential academic cycle.

Students have bought into the culture of professionalism. In 2005, a fourth-professional year student reported an inappropriate e-mail sent by a new first-professional year student to all classes and alerted student services personnel who were then able to effectively intervene. The Student Government Association continues to enhance professionalism expectations in the Student Honor Code and its bylaws and revisions, and the officers provide orientation to each incoming class. The Lambda Kappa Sigma chapter has added a Professionalism Committee. In the March 2006 ACPE re-accreditation report, the site evaluation team identified no issues with students' acceptance of professionalism; in fact, students were characterized as one of the School's strengths by being “articulate, forthright, and honest.” Also, the 2005-2006 Curriculum Committee Chair conducted a focus group with second-, third-, and fourth-professional year students for feedback on the use the skills-based assessment forms, including the professionalism criteria. There were no negative comments, and several responded that they liked the standardization and guidance provided by the detailed criteria. All students in each class will be surveyed in the future to determine whether they support the 4 professionalism criteria or not and the rationale for their responses.

The School is in the process of implementing new strategies to continue to promote a culture of professionalism within the School. Significant progress has been made with the implementation of a student-centered honor code, the Grievance Committee,8 which addresses violations of the honor code, didactic material in introductory courses, such as Pharmacy Practice and Education (PHAR 516), Introduction to Professional Practice I (PHPC 510), and Ethics in Pharmacy Practice (PHAR 523), and the adoption and implementation of professionalism criteria in the experiential courses. However, this is only the beginning. Faculty members are adopting the professional behavior criteria developed for experiential courses in selected didactic courses such as Effective Leadership and Advocacy (PHMY 598) and Patient-Centered Pharmacy Management I (PHAR532), which utilizes the pharmacy practice laboratory and the model pharmacy facility. By expanding the institutionalization of the professionalism criteria, the school will create a systematic approach that permeates all areas of the educational program.

The School hopes to implement other future initiatives, such as providing professionalism sensitivity training for residents and graduate students (who serve as teaching assistants and role models) and developing appropriate guidelines for professional communication and interaction with other health care practitioners. Additionally, the School will support seminars and activities that remind faculty and staff members that professionalism is expected from all members of the school community. Also, the School will implement a seminar series in which professionalism issues will be explored and forums will be held/created to discuss related topics. Recommendations and ideas generated in these forums will be used to create or modify guidelines or programs to continue to promote professionalism. The goal is to create an atmosphere for students in which professionalism becomes a lifelong skill, developed and practiced every day, even after they hang up their white coat.

For a culture of professionalism to succeed in an institution, there must be an institutional commitment with buy-in from all stakeholders. Is all this investment in resources worthwhile to the School at which only 2 professionalism failures occurred annually among 1,920 IPPEs and APPEs? If the desired outcome is 100% competence for the baseline professionalism expectations, then such processes are worthwhile to identify even 1 student who does not meet the professionalism standards. Fair and consistent application of these essential criteria and processes is necessary for these endeavors to succeed. Professional behavior among student pharmacists counts when all those involved in their education support the culture of professionalism and hold students accountable for their behavior.

CONCLUSION

Since 2001, a program to promote a culture of professionalism has been systematically and successfully implemented at the University of Maryland School of Pharmacy. Faculty members continue to support the 2 goals of establishing clear professionalism expectations and holding students accountable for professionalism. Considerable effort is expended on documentation, hearings, remediations, and follow-up, even though only a few students do not meet standards.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Dr. Stuart Haines and Mr. Richard Rumrill for their roles as co-developers of the initial professionalism criteria.

REFERENCES

- 1.Forni PM. Choosing Civility: The Twenty-Five Rules of Considerate Conduct. 1st ed. New York, NY: St. Martin's Press; 2002. pp. 7–23. [Google Scholar]

- 2. APhA-ASP/AACP-COD Task Force on Professionalism. White paper on pharmacy student professionalism. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2000; 40:96-102. Also available at http://www.aphanet.org/students/whitepaper.pdf. [PubMed]

- 3. APhA-ASP/AACP-COD Task Force on Professionalism. Toolkit for professionalism.2005. Available at http://www.aphanet.org/students/.

- 4.Purkerson Hammer D, Mason HL, Chalmers RK, Popovich NG, Rupp MT. Development and testing of an instrument to assess behavioral professionalism of pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2000;64:141–51. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hammer DP, Berger BA, Beardsley RS, Easton MR. Student professionalism. Am J Pharm Educ. 2003;67(3) Article 96. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boyle CJ, Morgan JA, Beardsley RS. Professionalism is more than a white coat: beyond rules and rituals [abstract]. Meeting Abstracts. 105th Annual Meeting, July 10-14, 2004, Salt Lake City, Utah. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68(2) Article 54. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyle CJ, Rumrill RE. Accountability for professionalism. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2002;42:308. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Student Discipline and Grievance, Academic Policies and Procedures, University of Maryland, School of Pharmacy. Available at: http://www.pharmacy.umaryland.edu/StudentAffairs/policies.htm Accessed May 9, 2006.