Abstract

Objective

Epidemiological, clinical and histological data suggest intriguing similarities between preeclampsia and graft-host-rejection. Granulysin, a novel biomarker of overall cellular immunity, is secreted by natural killer cells and cytotoxic T lymphocytes, which are associated with graft-host-rejection. Plasma granulysin was elevated in Japanese preeclamptic women.

Design and Methods

50 preeclampsia cases and 50 normotensive controls (USA) were studied. Plasma granulysin at delivery was determined using enzyme immunoassay. Logistic regression procedures were used to estimate odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Results

Granulysin were elevated in preeclampsia cases compared with controls (3.01±0.18 vs. 2.22±0.14 ng/ml, p<0.01). After adjusting for age, body-mass-index and race, women with higher granulysin concentrations (≥1.89 ng/ml) experienced a 2.9-fold (95%CI 1.1–7.8) increased preeclampsia risk compared with women with lower granulysin (<1.89 ng/ml).

Conclusions

These data offer further evidence of a predominant Th1 immune status associated with preeclampsia. Prospective studies are needed to determine whether granulysin is elevated early in pregnancy.

Keywords: granulysin, preeclampsia

Introduction

Preeclampsia has been recognized clinically since Hippocrates; however its aetiology and pathophysiology remain enigmatic. Over the past several decades, investigators have revealed that preeclampsia is associated with poor trophoblastic implantation [1, 2], excessive inflammatory response [3] and generalized maternal endothelial cell dysfunction [4]. Since the disorder occurs more commonly in primigravidae and in women with underlying collagen-vascular diseases [5], an immunological component has long been suspected. Positive associations of preeclampsia with molar pregnancies and multi-foetal pregnancies suggest that increased placental mass and foetal antigen load are also important pathophysiological characteristics of the disorder [6, 7]. Some investigators have linked pregnancy to the growth of an allograft where foetal trophoblast cells evade immune rejection and invade maternal tissue [8]. Uncomplicated pregnancies are characterized by a systemic inflammatory response that is exacerbated in preeclampsia [9]. Many cross-sectional and prospective studies have documented this pathophysiological aspect of preeclampsia using single or multiple biomarkers of cytokines [10, 11] or acute phase response proteins such as C-reactive protein [12]. Cytotoxic CD8+ T-cell (CTLs) and natural killer (NK) cell have been shown to be more prevalent in preeclampsia than in normal pregnant women using flow cytometry [13]. Importantly, placenta pathology indicate fibrin and complement deposition and "foam" cells in atherosis lesions, which resemble the histopathology of acute graft rejection [14]. These data indicate that preeclampsia is associated with T helper-1 cell (Th1) predominant profile - a dominant cell-mediated immunity.

Granulysin, a cytolytic granule protein of NK cells, CTL, and NK T cells, is also an antimicrobial protein [15]. It is active against a broad range of microbes including Gram-positive and gram negative bacteria, fungi and parasites [16]. Additionally, granulysin has been shown to possess antiviral activity [17]. Like tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), the protein also as anti-tumour properties [18]. Two molecular forms of granulysin, the 15-kDa precursor and 9-kDa mature form, are produced in these cells. Recently, Ogawa et al developed an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for measuring serum granulysin and reported serum granulysin is strongly associated with the activities of NK cells and cytotoxic T lymphocytes in both physiological and pathological settings [19]. Since the half-life of cellular-immunity-inducing cytokines (such as interleukin-2 (IL-2), TNF-α etc) is very short, serum level of these cytokines are difficult to detect. Serum levels of granulysin, however, are relatively higher and are thought to be more stable [19]. Thus, serum granulysin may be a useful novel marker of overall cell-mediated immunity.

Sakai et al [20], in their study of 21 women with preeclampsia and 50 controls, reported that serum granulysin concentrations were elevated in women with preeclampsia as compared with normotensive controls. The authors also noted that serum granulysin concentrations were positively correlated with mean blood pressure (r=0.51, p=0.02) among preeclampsia cases. These cross sectional data, coupled with previous reports of elevated mRNA expression of granulysin in transplant patients with acute allograft rejection [21–23] motivated our pilot study of granulysin in preeclamptic patients using available data of pregnant women in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. Our a priori hypothesis was that the risk of preeclampsia is increased with elevated maternal plasma granulysin concentrations.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

This case-control study was conducted from April 1998 to June 2002 at the Swedish Medical Center and Tacoma General Hospital in Seattle and Tacoma, Washington, respectively. This study has been described in detail elsewhere [24]. Preeclampsia cases were identified by daily surveillance of labour and delivery logs and confirmed by medical records using the then-current criteria of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists [5]. Women were recruited during their postpartum hospital stay. For this analysis, we used the most-current diagnosis criteria advocated by the National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Pregnancy [9]. Preeclampsia was defined as sustained pregnancy-induced hypertension with proteinuria. Hypertension was defined as sustained blood pressure readings of ≥140/90 mmHg (with readings taking place ≥ 6 hours apart) on or after 20 weeks gestation. Proteinuria was defined as urine protein concentration ≥30 mg/dl (or 1+ on a urine dipstick) on ≥2 random specimens collected ≥ 4 hours apart.

Controls were women with pregnancies uncomplicated by pregnancy-induced hypertension or proteinuria. Each day during the enrolment period, controls were numbered in the order in which they were admitted and delivered within two hours of a case, and were approached in the order in which they were identified by research personnel. All study subjects with pre-existing diabetes, chronic hypertension, autoimmune disease and renal disease were excluded from this analysis. We also restricted our study population to those having singleton. Hence, 128 preeclampsia cases and 484 control subjects were available for study. From those women, we randomly selected 50 preeclampsia cases and 50 controls for the maternal plasma granulysin analysis. We used STATA statistical software to draw random samples of study participants. This sampling was done without replacement of subjects already selected for participation in the current study. Power and sample size calculations indicated that we had greater than 90% power to detect a 25% increase in mean concentrations of plasma granulysin concentrations in preeclampsia cases versus control subjects. We also had approximately 80% power to detect a 3.0-fold increased risk of preeclampsia (p=0.05, two tailed) associated with elevated granulysin concentrations (defined as values above the median in controls).

The procedures used in this study were in agreement with the protocols approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Swedish Medical Center and Tacoma General Hospital, respectively. All participants provided written informed consent.

Data and Blood Sample Collection Procedures

A structured interview questionnaire, administered during the participants’ postpartum hospital stay, was used to collect information on maternal socio-demographic, medical, reproductive and life style characteristics during in-person interviews.

Non-fasting blood samples were collected in EDTA 10 ml Vacutainer tubes during the intrapartum period. These were protected from ultraviolet light, kept on wet ice and processed within 30 minutes of phlebotomy. Plasma decanted into cryovials was frozen at −70°C until analysis. Plasma granulysin concentrations were measured using ELISA methods as previously described [20]. In brief, antogranulysin monoclonal antibody (MoAb) RB1 (anti-15-kDa) was coated on microtitre plates at 5μg/ml in 100mM carbonate buffer at 40°C overnight. The plates were washed with phosphate-buffed saline (PBS) containing 0.1% Tween-20 and blocked with 10% foetal bovine serum in washing buffer (blocking buffer) at 37°C for 1–2h. Then, the plates were reacted at room temperature with plasma samples in blocking buffer for 2h and reacted with 0.1μg/ml of biotinylated RC8MoAb in blocking buffer for 1h. After washing, 0.05 U/ml of α-galactosidase-conjugated strptavidine (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland) were reacted. The plates were finally incubated with 0.4 mM of 4-methylumbelliferyl-α-D-galactosidase (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) containing 0.02% bovine serum albumin, 100 mM NaCl and 1 mM MgCl2 at 37°C for 17h. The enzyme reaction was then stopped with 100 mM glycine-NaOH (pH 10.3) and the fluorescence intensity was measured with Cyto Fluor 4000 fluorescence multi-well plate reader (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) with excitation and emission wavelength of 360 nm and 460nm, respectively. The detection limit for granulysin was 20 pg/ml. The intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation for the assays used were all <10%. All assays were performed without knowledge of pregnancy outcome.

Statistical Analysis

We examined frequency distributions of maternal socio-demographic characteristics and medical and reproductive histories according to case-control status. Associations of maternal plasma granulysin concentrations with some characteristics such as maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index and gestational age (GA) at delivery were estimated using Spearman’s correlation coefficients (ρ).

To estimate the relative association between preeclampsia and levels of maternal plasma granulysin, we categorized each subject according to tertiles or median determined by the distribution among controls. We used the lowest tertile or lower than median as the referent group, and estimated odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for each of the remaining categories. To assess confounding, we entered covariates into a logistic regression model one at a time, and then compared the adjusted and unadjusted odds ratios (OR) [25]. We considered and examined the following covariates as potential confounders in this analysis: maternal age, physical inactivity during pregnancy, maternal smoking status, maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) and gestational age at delivery. Final logistic regression models included covariates that altered unadjusted odds ratios by at least 10%. All analyses were performed using Stata 9.0 statistical software (Stata, College Station, TX). All continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard error (SE). All reported confidence intervals were calculated at the 95% level.

Results

The socio-demographic, medical, and reproductive characteristics for preeclamptic cases and controls are shown in Table 1. Compared with controls, cases tended to be unmarried, less educated, heavier, smokers during pregnancy, and to be physically inactive during pregnancy.

Table 1.

Distribution of preeclampsia cases and controls according to selected characteristics, Seattle and Tacoma, Washington, 1998–2002.

| Characteristics | Preeclampsia Cases | Control Subjects |

|---|---|---|

| (N=50) | (N=50) | |

| % | % | |

| Maternal Age at delivery ≥35years old | 32.0 | 34.0 |

| Maternal Age at delivery (years) | 30.6±1.11 | 32.3±0.7 |

| Maternal Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White/Non-Hispanic | 68.0 | 84.0 |

| Other | 26.0 | 14.0 |

| Missing | 6.0 | 2.0 |

| Unmarried | 24.0 | 18.0 |

| <12 Years of education | 24.0 | 4.0 |

| Nulliparous | 62.0 | 68.0 |

| Family history of chronic hypertension | 50.0 | 46.0 |

| Physical inactivity during pregnancy | 52.0 | 32.0 |

| Smoked During Pregnancy | 8.0 | 6.0 |

| Pre-Pregnancy Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 26.5±0.81* | 22.4±0.5 |

| Gestational age at delivery (weeks) | 34.1±0.51* | 39.7±0.2 |

| Maternal Plasma granulysin (ng/ml) | 3.01±0.181* | 2.22±0.14 |

| Indicated as median (inter-quartile range) | 2.73 (2.00, 3.82)** | 1.89 (1.50, 2.75) |

Mean ± SE.

P value from Student t test <0.01.

P value from Ranksum test <0.01.

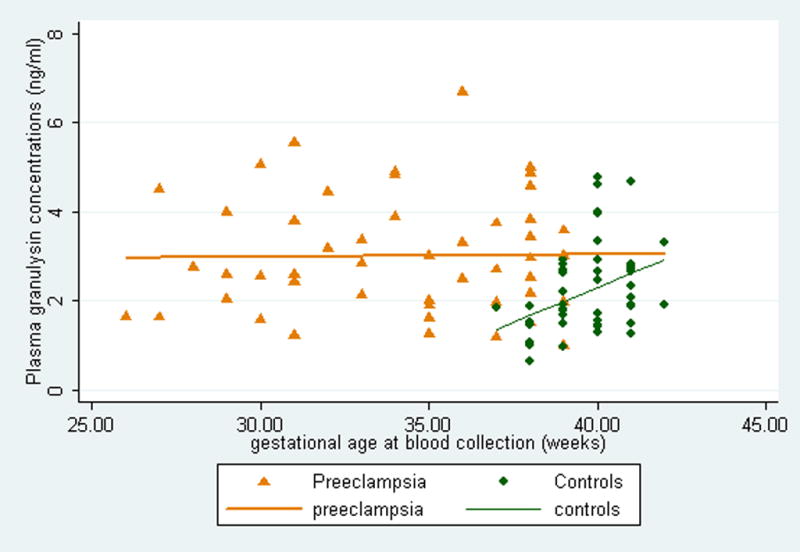

Granulysin concentrations were elevated in preeclampsia cases as compared with normotensive controls (3.01±0.18 vs. 2.22±0.14 ng/ml, p<0.01). Spearman correlation coefficients of granulysin concentrations with pre-pregnancy body mass index were significant in cases (ρ=0.32, p=0.03), but not so in controls (ρ=−0.09, p=0.57). However, the correlation with gestational age at delivery was significant in controls (ρ=0.40, p=0.004), but not in cases (ρ=−0.01, p=0.98). And the relation between plasma granulysin concentrations and gestational age at delivery are visually summarized for preeclampsia case and controls, respectively in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The scatter-plot and regression line of maternal plasma granulysin with gestational age at delivery according to cases and control status, Seattle and Tacoma, Washington, 1998–2002.

Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios (OR) of preeclampsia risk based on categories of maternal plasma granulysin are shown in Table 2. The corresponding unadjusted ORs for the tertiles were 1.0, 1.7 (95%CI: 0.6–4.8) and 3.1 (95%CI: 1.1–8.5). Adjustments for potential confounding by maternal pre-pregnancy BMI, maternal age at delivery and race/ethnicity, resulted in attenuations of ORs and associations were no longer statistically significant (1.0, 1.3 (95%CI: 0.4–4.4) and 1.9 (95%CI: 0.6–6.0)) We repeated logistic regression analyses after defining subjects according to whether they had granulysin concentrations above or below the median concentrations among controls. From these analyses, we noted that women with higher granulysin concentrations (≥1.89 ng/ml) had a 2.9-fold increased risk of preeclampsia as compared with compared with women who had lower concentrations (<1.89 ng/ml) (95%CI 1.1–7.8).

Table 2.

Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of preeclampsia risk according to different concentrations of maternal plasma granulysin, Seattle and Tacoma, Washington, 1998–2002.

| Granulysin (ng/ml) | Preeclampsia Cases (N=50) | Control Subjects (N=50) | Unadjusted OR (95%CI) | Adjusted OR (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All subjects | ||||

| Tertile1 (<1.69) | 9 | 17 | 1.0 (referent) | 1.0 (referent) |

| Tertile 2 (1.69–2.65) | 15 | 17 | 1.7 (0.6–4.8) | 1.3 (0.4–4.4) |

| Tertile3 (≥2.66) | 26 | 16 | 3.1 (1.1–8.5) | 1.9 (0.6–6.0) |

| <median (<1.89) | 9 | 25 | 1.0 (referent) | 1.0 (referent) |

| ≥median (≥1.89) | 41 | 25 | 4.6 (1.8–11.3) | 2.9 (1.1–7.8) |

| Restricted to term preeclampsia cases | ||||

| <median (<1.89) | 3 | 25 | 1.0 (referent) | 1.0 (referent) |

| ≥median (≥1.89) | 14 | 25 | 4.7 (1.2–18.3) | 2.8 (0.6–13.6) |

| Restricted to pre-term preeclampsia cases | ||||

| <median (<1.89) | 6 | 25 | 1.0 (referent) | 1.0 (referent) |

| ≥median (≥1.89) | 27 | 25 | 4.5 (1.6–12.8) | 3.2 (1.0–10.1) |

OR and 95% CI adjusted for pre-pregnancy body mass index (continuous), maternal age at delivery (continuous) and race (non-Hispanic White vs. other).

Given that all controls delivered at term (i.e., delivery after 37 completed weeks gestation), and that several preeclampsia cases were delivered preterm (i.e., delivery before 37 completed weeks gestation), we preformed sub-group analyses of term preeclampsia cases (N=17) versus term controls (N=50); and then repeated analysis of pre-term preeclampsia (N=33) versus term controls (N=50). We regarded these analyses, particularly the analysis that contrasted term preeclampsia cases with term controls, as being most optimally suited for controlling for potential confounding by gestational age at delivery. As can be seen in the middle section of Table 2, when analyses were restricted to term preeclampsia cases and term controls, we noted elevated granulysin concentrations were associated with a 2.8-fold increased preeclampsia risk (95% CI 0.6–13.6). When analyses were restricted to preterm cases and thus were contrasted with term controls (a situation where confounding would likely be at a maximum), we noted that elevated granulysin concentrations were associated with a 3.2-fold increased preeclampsia risk (95% CI: 1.0–10.1). Taken together, these stratified analyses and our primary analysis suggest that gestational age at delivery may not have been a major confounder of the granulysin and preeclampsia association in our study population.

DISCUSSION

Our report extends the current literature by documenting a relation between granulysin concentration and preeclampsia risk after adjustment for confounders. Our results are consistent with a previous study [20], which demonstrated elevated serum levels of granulysin in preeclamptic Japanese women (3.8±1.8 ng/ml in severe preeclamptic cases and 2.6±0.6 ng/ml in mild cases) as compared with normotensive controls (1.9±0.8 ng/ml). Our results are also compatible with those studies indicating cytotoxic T-cell and natural killer cell are activated in preeclampsia [13] and those in-vitro reports indicting that phytohaemagglutinin (PHA)-stimulated 1L-2 and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) production are significantly higher (P<0.001) in pre-eclamptic patients than in the controls [26]. IL-2 and IFN-γ are synthesized by Th1 cells. Our results also agree with the animal model by adoptively transferring activated BALB/c Th1-like splenocytes into allogeneically pregnant BALB/c female mice during late gestation. This cell transfer provoked preeclampsia symptoms---increased blood pressure and glomerulonephritis accompanied by proteinuria [27]. However, our results do not support the reports from Paescke et al who report that preeclampsia is not associated with changes in the levels of regulatory T cells in peripheral blood [28].

Our results are also consistent with the reports concerning granulysin and renal allograft rejection (the similar scenario of preeclampsia). For example, Sarwal et al examined granulysin expression in human renal allograft rejection and found that granulysin mRNA and protein in peripheral blood lymphocytes and allograft tissues were significantly increased during both acute rejection and infection [21].

Elevated plasma granulysin concentrations in preeclampsia may reflect an exacerbated inflammatory reaction (predominant cellular immunity) among women with the disorder. Results from in vitro studies have indicated that positively charged granulysin binds to negatively charged phospholipids on cell membranes [29]; and that once bound to target cell surfaces, granulysin induces an increase in intracellular calcium and efflux of intracellular potassium [30]. Sphingomylinase is activated, generating ceramide that leads to cell death over hours [31]. The changes in intracellular Ca+2 and K+ are associated with much more rapid induction of lysis involving mitochondrial damage, the release of cytochrome C and apoptosis inducing factor, blockade of oxidative metabolism and electron transport, the activation of caspases and programmed cell death (apoptosis) by endonuclease activation and chromosome breakdown [29, 30]. Recently, it has been shown that granulysin also acts as a chemoattractant for monocytes, CD4+ and CD8+ memory (CD45RO) but not naïve (CD45RA) T cells, NK cells, and mature, but not immature, monocyte-derived dendritic cells [32]. Hence, granulysin may help recruit immune cells to sites of inflammation. The inflammation and apoptosis changes in trophoblast cells will hamper their capability of endovascular invasion which is essential in the development of normal placenta [33, 34].

Several important limitations must be considered when interpreting our results. First, because of the cross-sectional design of our study, we cannot determine whether the observed case-control differences in plasma granulysin concentrations preceded preeclampsia or whether the differences may be attributed to preeclampsia-related physiological alterations. Prospective longitudinal studies with serial measurements of granulysin concentrations in women with and without preeclampsia are required to confirm and expand upon our observations. Second, differential misclassification of maternal plasma granulysin concentrations is unlikely, as all laboratory analyses were conducted without knowledge of participants’ pregnancy outcome. Finally, although we controlled for multiple confounding factors, we cannot with certainty conclude that the odds ratios reported are unaffected by residual confounding.

We have shown that plasma granulysin concentrations are positively associated with preeclampsia risk. Our findings corroborate those reported earlier (13). Future prospective studies designed to measure determinants of granulysin concentrations in normal pregnancy; and to assess preeclampsia risk in relation to concentrations measured in early pregnancy are needed to further elucidate the potential merits of granulysin as a possible biomarker of preeclampsia pathogenesis and a clinical risk factor.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by awards from the National Institutes of Health (HD/HL R01 34888 and HD/HL R01 32562.). This research was also supported by grants from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan [grant-in Aid for Scientific Research (B)-17390447 and (C)-18591797 and Grant-in-Aid for Exploratory Research 18659482].

The authors are indebted to the participants of the ALPHA Study for their cooperation. They are also grateful for the technical expertise contributed by staff in Center for Perinatal Studies.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Pijnenborg R. The placental bed. Hypertens Pregnancy. 1996;15:7–23. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou Y, Damsky CH, Fisher SJ. Preeclampsia is associated with failure of the human trophoblasts to mimic a vascular adhesion phenotype. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:2152–2164. doi: 10.1172/JCI119388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Redman CWG, Sacks GP, Sargent IL. Preeclampsia: an excessive maternal inflammatory response to pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180:499–506. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70239-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roberts JM, Taylor RN, Musci TJ, Rodgers GM, Hubel CA, McLaughlin MK. Preeclampsia: an endothelial cell disorder. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;161:1200–1204. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(89)90665-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Hypertension in Pregnancy. ACOG Technical Bull. 1996;219:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duckitt K, Harrington D. Risk factors for pre-eclampsia at antenatal booking: systematic review of controlled studies. BMJ. 2005;330:565–571. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38380.674340.E0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lo YMD, Leung TN, Tein MSC, Sargent IL, Zhang J, Lau TK, Haines CJ, Redman CWG. Quantitative abnormalities of fetal DNA in maternal serum in preeclampsia. Clin Chem. 1999;45:184–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thellin O, Coumans B, Zarzi W, Igout A, Heinen E. Tolerance to foeto-maternal “graft”: ten ways to support a child for nine months. Curr Opin Immunol. 2000;12:731–7. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(00)00170-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Report of the National High Blood Pressure Education Program working group on blood pressure in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:s1–s2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams MA, Farrand A, Mittendorf R, Sorensen TK, Zingheim RW, O’Reilly GO, King IB, Zebelman AM, Luthy DA. Maternal second-trimester serum tumor necrosis factor-α soluble receptor p55 (sTNFp55) and subsequent risk of preeclampsia. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;149:323–329. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sunder-Plassmann G, Derfler K, Wagner L, Stockenhuber F, Endler M, Nowothy C, Balcke P. Increased serum activity of interleukin-2 in patients with preeclampsia. J Autoimmunol. 1989;2:203–205. doi: 10.1016/0896-8411(89)90156-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qiu C, Luthy DA, Zhang C, Walsh SW, Leisenring WM, Williams MA. A prospective study of maternal serum C-reactive protein concentrations and risk of preeclampsia. Am J Hypertension. 2004;17:154–160. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2003.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saito S, Umekage H, Sakamoto Y, Sakai M, Tanebe K, Sasaki Y, Morikawa H. Increased Th1-type immunity and decreased Th2-type immunity in patients with preeclampsia. Am J Reprod Immunol. 1999;41:297–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1999.tb00442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kitzmiller IL, Benirschke K. Immunofluorescent study of placental bed vessels in preeclampsia of pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1973;115:248–251. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(73)90293-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gansert JL, Kiebler V, Engele M, Wittke F, Rollinghoff M, Krensky AM, Porcelli SA, Modlin RL, Stenger S. Human NKT cells express granulysin and exhibit antimycobacterial activity. J Immunol. 2003;170:3154–3161. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.6.3154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stenger S, Rosat JP, Bloom BR, Krensky AM, Modlin RL. Granulysin: a lethal weapon of cytolytic T cell. Immunol Today. 1999;20:390–394. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(99)01449-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hata A, Zerboni L, Sommer M, Kaspar AA, Clayberger C, Krensky AM, Arvin AM. Granulysin blocks replication of varicella-zoster virus and triggers apoptosis of infected cells. Viral Immunol. 2001;14:125–133. doi: 10.1089/088282401750234501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Z, Choice E, Kasper A, Hanson D, Okada S, Lyu SC, Krensky AM, Clayberger C. Bactericidal and tumoricidal activities of synthetic peptides derived from granulysin. J Immunol. 2000;165:1486–1490. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.3.1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ogawa K, Takamori Y, Suzuki K, Nagasawa M, Takano S, Kasahara Y, Nakamura Y, Kondo S, Sugamura K, Nakamura M, Nagata K. Granulysin in human serum as a marker of cell-mediated immunity. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:1925–1933. doi: 10.1002/eji.200323977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sakai M, Ogawa K, Shiozaki A, Yoneda S, Sasaki Y, Nagata K, Saito S. Serum granulysin is a marker for Th1 type immunity in pre-eclampsia. Clin Exp Immunol. 2004;136:114–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02414.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sarwal MM, Jani A, Chang s, Huie P, Wang Z, Salvatierra O, Jr, Clayberger C, Sibley R, Krensky AM, Pavlakis M. Granulysin expression is a marker of acute rejection and steroid resistance in human renal transplantation. Human Immunol. 2001;62:21–31. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(00)00228-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kotsch K, Mashreghi MF, Bold G, Tretow P, Beyer J, Matz M, Hoerstrup J, Pratschke J, Ding R, Suthanthiran M, Volk HD, Reinke P. Enhanced granulysin mRNA expression in urinary sediment in early and delayed acute renal allograft rejection. Transplantation. 2004;77:1866–1875. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000131157.19937.3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soccal PM, Doyle RL, Jani A, Chang S, Akindipe OA, Poirier C, Pavlakis M. Quantification of cytotoxic T-cell gene transcripts in human lung transplantation. Transplantation. 2000;69:1923–1927. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200005150-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang C, Williams MA, King IB, Dashow EE, Sorensen TK, Frederick IO, Thompson ML, Luthy DA. Vitamin C and the risk of preeclampsia--results from dietary questionnaire and plasma assay. Epidemiology. 2002;13:409–416. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200207000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rothman KJ, Greenland S. Modern Epidemiology. 2. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Darmochwal-Kolarz D, Leszczynska-Gorzelak B, Rolinski J, Oleszczuk J. T helper 1- and T helper 2-type cytokine imbalance in pregnant women with pre-eclampsia. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1999;86:165–170. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(99)00065-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zenclussen AC. A novel mouse model for preeclampsia by transferring activated th1 cells into normal pregnant mice. Methods Mol Med. 2006;122:401–412. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-989-3:401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paeschke S, Chen F, Horn N, Fotopoulou C, Zambon-Bertoja A, Sollwedel A, Zenclussen ML, Casalis PA, Dudenhausen JW, Volk HD, Zenclussen AC. Pre-eclampsia is not associated with changes in the levels of regulatory T cells in peripheral blood. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2005;54:384–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2005.00334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaspar AA, Okada S, Kumar J, Poulain FR, Drouvalakis KA, Kelekar A, Hanson DA, Kluck RM, Hitoshi Y, Johnson DE, Froelich CJ, Thompson CB, Newmeyer DD, Anel A, Clayberger C, Krensky AM. A distinct pathway of cell-mediated apoptosis initiated by granulysin. J Immunol. 2001;167:350–356. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.1.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okada S, Li Q, Whitin JC, Clayberger C, Krensky AM. Intracellular mediators of granulysin-induced cell death. J Immunol. 2003;171:2556–2562. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.5.2556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gamen S, Hanson DA, Kaspar A, Naval J, Krensky AM, Anel A. Granulysin-induced apoptosis. I. Involvement of at least two distinct pathways. J Immunol. 1998;161:1758–1764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deng A, Chen S, Li Q, Lyu S-C, Clayberger C, Krensky AM. Granulysin, a cytolytic molecule, is also a chemoattractant and proinflammatory activator. J Immunol. 2005;174:5243–5248. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.9.5243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaufmann P, Black S, Huppertz B. Endovascular trophoblast invasion: implications for the pathogenesis of intrauterine growth retardation and preeclampsia. Biol Reprod. 2003;69:1–7. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.014977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.DiFederico E, Genbacev O, Fisher SJ. Preeclampsia is associated with widespread apoptosis of placental cytotrophoblasts within the uterine wall. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:293–301. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65123-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]