Abstract

Human GATA3 haploinsufficiency leads to HDR (hypoparathyroidism, deafness and renal dysplasia) syndrome, demonstrating that the development of a specific subset of organs in which this transcription factor is expressed is exquisitely sensitive to gene dosage. We previously showed that murine GATA-3 is essential for definitive kidney development, and that a large YAC transgene faithfully recapitulated GATA-3 expression in the urogenital system. Here we describe the localization and activity of a kidney enhancer (KE) located 113 kbp 5' to the Gata3 structural gene. When the KE was employed to direct renal system-specific GATA-3 transcription, the extent of cell autonomous kidney rescue in Gata3-deficient mice correlated with graded allelic expression of transgenic GATA-3. These data demonstrate that a single distant, tissue-specific enhancer can direct GATA-3 gene expression to confer all embryonic patterning information that is required for successful execution of metanephrogenesis, and that the dosage of GATA-3 required has a threshold of between 50 and 70% of diploid activity.

Keywords: Gata3, kidney, rescue, enhancer, allelic series, haploinsufficiency

Introduction

Mammalian kidney morphogenesis progresses through three sequential stages with the first two embryonic kidneys, the pronephros and mesonephros, being transitory structures (Dressler, 2002; Gilbert, 2000; Kuure et al., 2000). By late embryonic day (e) 9, the nephric duct has fully extended posteriorly. The definitive kidney begins to develop at e11 when the ureteric bud (UB) sprouts from the nephric duct. This initial sprouting is triggered by glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) secreted from the metanephric blastema (Davies and Fisher, 2002; Sainio et al., 1997). A variety of additional morphogenetic signals lead to further outgrowth and dichotomous branching of the UB to form the mature renal collecting system (Davies and Fisher, 2002; Yu et al., 2004). The UB in turn signals to the surrounding nephrogenic mesenchyme, inducing it to undergo epithelial differentiation to ultimately form much of the nephron.

Of the germline mutations that have been analyzed in mice, loss-of-function alleles for the genes encoding transcription factors Lim1, Pax2, Pax2 plus Pax8 and GATA-3 most often lead to extension failure of the nephric duct (Bouchard et al., 2002; Lim et al., 2000; Shawlot and Behringer, 1995; Tsang et al., 2000). GATA-3 belongs to a six-member family of transcription factors that share conserved zinc fingers, which recognize the consensus sequence (A/T)GATA(A/G) (Ko and Engel, 1993; Merika and Orkin, 1993; Yamamoto et al., 1990). GATA-3 is expressed in many tissues and cell types, and has been shown in several cases to play essential roles in their differentiation (George et al., 1994; Hendriks et al., 1999; Kaufman et al., 2003; Lakshmanan et al., 1998; Lim et al., 2000; Ting et al., 1996; van der Wees et al., 2004; van Doorninck et al., 1999; Zheng and Flavell, 1997). Germ line deletion of murine Gata3 was initially reported to result in grossly normal Gata3 heterozygous mutant mice (Pandolfi et al., 1995), while Gata3 homozygous mutants die at midgestation of noradrenergic insufficiency leading to secondary cardiac failure (Lim et al., 2000). Pharmacologic rescue of GATA-3-deficient embryos (to late gestation) with synthetic noradrenaline intermediates revealed an array of mutant phenotypes, including renal agenesis, that were previously masked by the early in utero lethality (Lim et al., 2000).

To facilitate systematic and rapid isolation of regulatory cis-elements within any extended genomic domain, we previously reported the use of YACs (Lakshmanan et al., 1999; Zhou et al., 1998) and BAC-traps (Khandekar et al., 2004) to assess large swaths of the genome for enhancer activity in vivo. This led to the identification and crude localization of a Gata3 kidney enhancer lying within a 662 kbp YAC. To evaluate the in vivo contribution of an enhancer to a given biological process, we proposed to establish the necessary and sufficient contribution of a regulatory protein under the control of any enhancer to a discrete developmental event. Here, we describe the localization of a Gata3 kidney enhancer (KE) that lies 113 kbp 5' to the structural gene, and the in vivo interrogation of its contribution to generation of the definitive kidney.

To evaluate the capacity of the enhancer to fully delineate GATA-3 functions during nephrogenesis, we generated transgenic lines that expressed tissue-specific GATA-3 at various abundances relative to its endogenous level under the direct transcriptional control of the isolated KE. KE-directed GATA-3 transgenes (TgKE-G3) were then examined in Gata3 null (lacZ knock-in) mice (Gata3z/z:TgKE-G3) in order to assess their ability to specifically rescue metanephrogenesis. In the rescued compound mutants, the degree of renal development is directly proportional to the transgene-derived GATA-3 abundance, reflecting GATA-3 gene dosage dependence in executing the nephrogenic program as seen in HDR patients. Compound mutants with Tg expression of greater than 50% of endogenous GATA-3 levels undergo normal nephrogenesis, while equal to or less than 50% levels of GATA-3 result in a spectrum of intermediate defective nephric duct and ureteric bud phenotypes in midgestation as well as various deficiencies in the definitive kidneys of late gestation embryos. The renal phenotypic variations seen in the partially rescued compound mutants are in some ways reminiscent of the spectrum of highly variable clinical nephric defects encountered in GATA3 haploinsufficient HDR syndrome patients, suggesting that Gata3 compound mutant mice might represent a unique experimental model to study kidney deficiencies observed in the human condition.

Results

Localization of a distant Gata3 kidney enhancer

Previously, we generated transgenic lines harbouring the B125Z mouse Gata3 YAC (the genome sequence-revised endpoints are −451 to +211 kbp, with respect to the GATA-3 translational start site; Lakshmanan et al., 1998; Lakshmanan et al., 1999), which was tagged with a lacZ reporter gene (Lakshmanan et al., 1999). Detailed analyses of B125Z transgenic lines indicated that β-galactosidase staining was detected throughout early and definitive nephrogenesis, consistent with previous in situ hybridization studies (George et al., 1994; Labastie et al., 1995; Lakshmanan et al., 1999). Detailed pulsed-field gel electrophoresis analyses indicated that one line (#71) harboring a 5’ truncated YAC [with a breakpoint that mapped imprecisely between −70 and −116 (+/−20) kbp] still retained urogenital lacZ expression (data not shown, and Lakshmanan et al., 1999). Previous transgenic analyses of two other smaller YACs indicated that B124Z (spanning −451 to +69 kbp), but not C4Z (−40 to +69 kbp of the Gata3 locus), could recapitulate urogenital lacZ staining (Lakshmanan et al., 1998, and unpublished). These and other observations allowed us to conclude deductively that a kidney enhancer (KE) must reside in the interval between −40 and −116 kbp 5’ to the Gata3 structural gene. We therefore performed end fragment rescue to retrieve terminal genomic sequences from Gata3 YACs that had 3’ endpoints lying within that interval (B143 and B157; Fig. 1A). A rescued 9.2 kbp EcoRI genomic DNA fragment was recovered from the YAC B143 3’ terminus, which localized to −110 kbp (Fig. 1B1; data not shown and Lakshmanan et al., 1998).

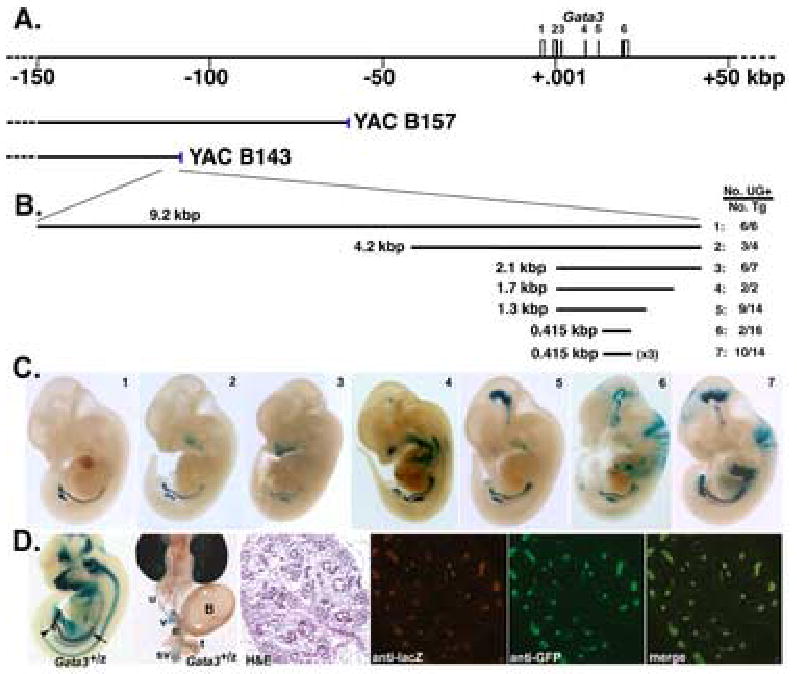

Figure 1. Localization of a Gata3 kidney enhancer.

A. The murine Gata3 locus is schematically illustrated with the six exons indicated. The GATA-3 translational initiation site in exon 2 is designated as nucleotide 1. The approximate 3’ endpoints of the B143 and B157 YACs (Lakshmanan et al., 1999) are indicated. B. Individual test constructs (1–7, with sizes indicated) were cis-linked to the Gata3 minimal promoter driving lacZ reporter gene, and then tested for urogenital enhancer activity in F0 transgenic assays. The transgenic data for each construct is summarized on the right with the numbers representing the total number of embryos positive for urogenital X-gal staining and lacZ transgene(s) as determined by PCR genotyping, respectively. For generating GATA-3 transgenic lines in the rescue experiments (below), the lacZ reporter gene in construct 5 was replaced by GATA-3 cDNA. C. Linearized expression constructs (1–7, see B) were microinjected into fertilized oocytes. e11.5–12.5 embryos were stained for β-galactosidase activity. All test constructs were capable of driving lacZ expression in the nephric duct and the branching ureteric bud, mimicking the X-gal staining pattern seen in Gata3+/z embryos. The number shown in the upper right hand corner corresponds to the number of the injected test construct (B.). D. An X-gal-stained whole mount e11.5 Gata3+/z embryo. Note the staining in the nephric duct and the bifurcating ureteric bud, indicated by the arrow and arrowhead, respectively (left panel). The urogenital system from a male neonate of a stable transgenic line harboring construct 5 (B) was subjected to X-gal staining (second panel from left). Note that X-gal stains the kidneys, the ureters and the Wolffian duct-derived genital tracts, as previously reported in Gata3 lacZ YAC transgenic mice (Lakshmanan et al., 1999). B, bladder; e, epididymis; sv, seminal vesicles; t, testis; u, ureter; v, vas deferens. (Third through sixth panels) A kidney section from an e15.5 Gata3+/z embryo bearing transgene construct 5 directing eGFP reporter expression was co-stained with anti-β-galactosidase and anti-GFP antibodies, conjugated with Cy3 and FITC fluorochromes, respectively, and then post-stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Note the co-localization of both fluorescent signals in the merged image (far right panel).

To determine whether the rescued B143 3’ end fragment contained kidney enhancer activity, we subcloned it into pG3lacZ (formerly named −308placZ; see Methods; Lieuw et al., 1997) for founder (F0) transgenic analysis (Fig. 1B). X-gal staining was detected in the nephric duct and the UB of all (6/6) e11.5 transgenic embryos (Fig. 1C1); the urogenital β-galactosidase staining pattern recapitulated that observed in whole mount X-gal-stained B125Z transgenic (Lakshmanan et al., 1999) as well as heterozygous Gata3 lacZ knock-in embryos (first panel from left, Fig. 1D, Gata3+/z; Hendriks et al., 1999; van Doorninck et al., 1999). Hence, we concluded that the 9.2 kbp end fragment recovered from YAC B143 contains a Gata3 KE. Further analysis resulted in the experimental refinement of this KE activity to a 1.3 kbp fragment that recapitulated the urogenital expression pattern in the majority of e11.5/e12.5 transgenic F0 embryos (Fig. 1B2–1B5 and 1C2–1C5).

To ascertain if the 1.3 kbp KE-directed lacZ reporter gene expression recapitulated the temporal profile of Gata3, we generated stable lines of this reporter construct. When examined during early- to mid-embryogenesis, transgene expression was strictly confined to the developing nephric ducts, and later in the sprouting ureteric buds, of e9.0–10.5 transgenic embryos (Supplemental Figure 1). This mirrored the temporal staining profile in Gata3+/z embryos with similar numbers of somites, which however displayed a more extensive X-gal staining pattern in tissues in addition to nephric derivatives. Thus, the 1.3 kbp KE was capable of activating reporter gene expression when endogenous GATA-3 expression was initiated. By birth, the transgene is expressed in the epididymus, seminal vesicles and vas deferens of transgenic males in addition to the kidneys and ureters (second panel from left, Fig. 1D), as do YAC B125Z transgenic and Gata3+/z neonates (Lakshmanan et al., 1998; below).

To verify coincident expression at the cellular level, we replaced the reporter gene in pG3lacZ with eGFP and generated transgenic lines bearing pG3GFP cis-linked to the 1.3 kbp KE fragment (Fig. 1B5). After crossing to Gata3+/z mice, the kidneys of compound mutant (Gata3+/z:TgKE-GFP) neonates were examined by immunofluorescent staining. Fully coincident staining (Fig. 1D, merge) of transgenic (Fig. 1D, anti-GFP) and endogenous (Fig. 1D, anti-β-gal) gene products was observed. Hence, the KE recapitulates the authentic spatiotemporal expression pattern of endogenous GATA-3 in the kidney.

To further refine the limits of the Gata3 kidney enhancer, we examined conserved genomic sequences from comparable domains of the Gata3 locus across several vertebrate species, including human, rat, dog and chicken. Within the 1.3 kbp, a non-repetitive, non-genic conserved sequence element (CSE) of 415 bp shared the greatest identity among all species examined (Fig. 1B6). In the mouse Gata3 locus, this CSE lies 113 kbp 5’ to the translational initiation site. To determine whether the CSE was also sufficient to direct urogenital expression, it was cis-linked singly or in triplicate (Fig. 1B6, 1B7) to pG3lacZ and examined in F0 transgenic assays. The CSE conferred correct lacZ patterning in the developing urogenital system of only a small fraction (2/16) of transgenic founders (Fig. 1C6). In contrast, triplication of the CSE directed urogenital system-specific lacZ expression in the majority of transgenic embryos (10/14; Fig. 1C7). Therefore subsequent transgenic experiments were performed using the larger 1.3 kbp KE (Fig. 1B5) rather than the 415 bp minimal CSE.

Generation and characterization of KE-directed GATA-3 transgenes

The eGFP gene in KEpG3GFP (Fig. 1B5 and 1C, anti-GFP) was replaced by a full-length GATA-3 cDNA (Ko et al., 1991) and used to generate transgenic animals, which were identified by PCR and Southern blotting analyses. Eighteen independent lines (Fig. 2A) bearing from 1 to 14 transgene copies were recovered.

Figure 2. Characterization of KE-directed GATA-3 transgenes.

A. Southern blot analysis of KE-GATA-3 transgenic lines. BamHI-digested genomic DNAs of independent TgKE-G3 lines were hybridized with radiolabelled probe synthesized using a 1 kbp EcoRI/AflII genomic fragment bearing the Gata3 KE. Transgene copy numbers were determined by densitometry of this and other blots (using the GATA-3 3' UTR as probe; not shown) and varied from 1 to 14. B. RT-PCR analysis of KE-GATA-3 line TgH3. RNA from the indicated tissues was reverse-transcribed into cDNA and then amplified using primers specific for transgene-derived (Tg) or endogenous (endo) GATA-3 mRNA (Methods). A non-transgenic littermate (non-Tg) was employed as the negative control for the transgene-specific PCR primers, while HPRT mRNA was used as the positive control for both RNA isolation and first strand cDNA synthesis. Legend: K, kidney; Th, thymus; Li, liver; H, heart; Lu, lung; Mb, midbrain; GI, small intestine; B, bone; Sk, skin. C. Semi-quantitative RT-PCR analysis of GATA-3 mRNA from representative transgenic lines. RNAs from e16.5 Gata3+/+ kidneys of TgH14, TgH3 and TgB6 lines were subjected to cDNA synthesis and two-fold serial dilutions of the cDNA were analyzed using either transgene-specific (Tg) or endogenous GATA-3-specific (endo) primers (Methods).

To characterize the tissue specificity of each transgenic line, we performed RT-PCR on total RNA isolated from individual tissues of Gata3+/+ Tg-positive and -negative littermates with primers that distinguished between endogenous and Tg-derived GATA-3 mRNAs (Methods). These analyses demonstrated that in some lines, such as H3, properly spliced Tg-derived GATA-3 transcripts were detected exclusively in the kidneys (Fig. 2B), whereas endogenous GATA-3 mRNA was detected in many other tissues where Gata3 is normally expressed (Fig. 2B and data not shown; George et al., 1994; Yamamoto et al., 1990). In other lines, however, the transgenes were also expressed ectopically, probably reflecting promoter activation exerted by cis elements located in the vicinity of random Tg integration sites (data not shown).

To quantify Tg expression levels relative to endogenous GATA-3 mRNA in the kidneys, we performed semi-quantitative RT-PCR under conditions of limiting template dilution or amplification cycle number. Multiple samples were examined in triplicate. In the line that expressed transgenic GATA-3 most abundantly, H14 (Fig. 2C), Tg-derived mRNA was detected at 70% of diploid abundance, while a second line, H3 (Fig. 2C), expressed the TgKE-G3 at 50% of wild type diploid levels. Two intermediate lines, G6 and H12, expressed Tg-specific mRNAs at 40% or 30% of diploid expression levels, respectively (data not shown), while most other lines (e.g. B6, 5% of wild type GATA-3 abundance, Fig. 2C) expressed transgenic GATA-3 at, or less than, 5% of endogenous levels. None of the transgenic lines exhibited visible gain of function phenotypes in the wild type genetic background.

KE-directed GATA-3 expression rescues renal organogenesis in GATA-3-deficient mice

We wished to determine whether the 1.3 kbp Gata3 KE was sufficient to direct GATA-3 reconstitution of the entire nephrogenic developmental program. To address this question, we assessed the rescue potential of each of the KE-directed transgenes in a Gata3 null background. The five well characterized Tg lines expressing high (H14 and H3), intermediate (G6 and H12) or low (B6) GATA-3 mRNA levels were independently interbred with Gata3+/z mice to generate compound mutant progeny (Gata3+/z:TgKE-G3). Pregnant dams from Gata3+/z x Gata3+/z:TgKE-G3 intercrosses were fed synthetic catechol intermediates to overcome the midgestational lethality normally observed in Gata3 null embryos (Lim et al., 2000). Embryos (e11.5–e16.5) were subjected to X-gal staining and PCR genotyping. In general, the expected Mendelian complement of all possible genotypes was observed, but with fewer homozygous mutants recovered as gestation progressed (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of genotypes from Gata3+/z X Gata3+/z:TgKE-G3 matings

| Transgene | Gata3+/+ | Gata3+/z | Gata3z/z | Gata3+/+:Tg | Gata3+/z:Tg | Gata3z/z:Tg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TgH14 (70%)* | 19 | 35 | 13 | 22 | 54 | 27 |

| TgH3 (50%) | 17 | 27 | 8 | 18 | 26 | 11 |

| TgG6 (40%) | 7 | 23 | 9 | 12 | 12 | 8 |

| TgH12 (30%) | 17 | 30 | 17 | 11 | 24 | 12 |

| TgB6 (5%) | 16 | 30 | 8 | 12 | 29 | 14 |

| Total (expected)** | 76 (72) | 145 (145) | 55 (72) | 75 (72) | 145 (145) | 72 (72) |

Embryos (e10.5–e16.5) were collected from pregnant dams fed with catechol intermediates to rescue the noradrenaline deficiency.

Percentages in parentheses indicate the expression levels of transgene(s) relative to wild type endogenous GATA-3 diploid levels.

Expected based on a Mendelian distribution of heterozygotes.

In e16.5 Gata3 heterozygous mutants, a full complement of normal genitourinary structures was observed, with no apparent defects in either organ size or morphology (Fig. 3B, C) in comparison to wild type littermates (Fig. 3A). In contrast, while the majority of the e11.5 Gata3+/z embryos developed long, well-formed nephric ducts and generated normally branching ureteric buds (Fig. 3D), we infrequently noticed accessory ureteric buds (Fig. 3E and 3F; arrowheads) in e11.5 Gata3+/z embryos (summarized in Table 2) that could be ascribed to Gata3 haploinsufficiency. This haploinsufficient defect is both transitory and fully compensated by the time definitive morphogenesis nears completion (e16.5) since aberrant kidneys were not observed in late gestational or adult heterozygotes (Fig. 3B, C).

Figure 3. Haploinsufficient urogenital phenotype in Gata3+/z embryos.

Whole mount urogenital systems recovered from e16.5 non-transgenic Gata3+/+ male (A), Gata3+/z male (B) or Gata3+/Z female (C) embryos stained for β-galactosidase activity. Both macroscopic inspection and detailed histological analyses have failed to yield evidence for any morphological aberrations in urogenital structures. D–F. Urogenital systems isolated en bloc from individual e11.5 Gata3+/z mutants with nephric duct and ureteric bud developmental variations. Panel D is a urogenital filet taken from a Gata3+/z embryo; the majority of e11.5 embryos displayed similar morphology, including a smooth nephric extension that contacted the urogenital sinus and a developing ureter terminated by a singly bifurcated bud. E. A small accessory bud adjacent to the ureteric bud proper is evaginating from the nephric duct (arrowhead). F. A fully duplicated ureteric bud (arrowhead).

Table 2.

Nephric duct and ureteric bud phenotypes in e11.5/12.5 Gata3+/z, Gata3z/z:Tg and Gata3z/z embryos

| Genotype | Complete ND | Shortened ND | ND on BW | No ND | Accessory UB | Separate “floating” UB | No UB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gata3+/z | 21/21 (B)* | 2/21 | |||||

| TgHi:Gata3z/z | 12/12 (B) | 1/12** | |||||

| TgInt:Gata3z/z | 4/8 (B) | 1/8 (B)

1/8 (U) |

1/8 (U) | 1/8 | 1/8 (B)

1/8 (U) |

1/8 | |

| TgLo:Gata3z/z | 1/5 (B)

2/5 (U) |

4/5 (U) | 2/5 (U) | 5/5 | |||

| Gata3z/z | 1/13 (U) | 1/13 (U) | 11/13 (B)

2/13 (U) |

13/1

3 |

TgHi, H14 and H3; TgInt, G6 and H12; TgLo, B6. Complete ND = nephric duct (ND) fully extended beyond the normal ureteric budding site; Shortened ND = nephric duct failing to extend bilaterally (B) or unilaterally (U) to or beyond the normal ureteric budding site; ND on BW = shortened ND that veered laterally to terminate into the body wall instead of extending caudally towards the cloaca; No ND = no visible caudal extension of ND beyond the anterior mesonephric tubules; Accessory UB = smaller, duplicated ureteric bud; Separate, “floating” UB = a discontinuous, ureteric bud associated with shortened ND; No UB = lack of visible ureteric buds.

# affected/total # of embryos.

A TgH3 embryo.

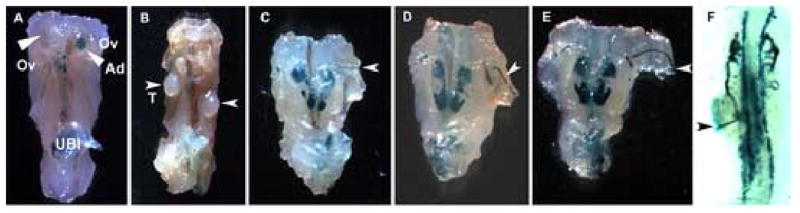

Consistent with previous observations, pharmacologically rescued e16.5 Gata3z/z embryos were most often anephric (Lim et al., 2000). Gata3z/z female and male embryos also lacked uteri or epididymi/vasa deferentia derived from the (GATA-3-negative) Mullerian or nephric/Wolffian ducts, respectively (Fig. 4A, B). The latter observations are consistent with those of Kobayashi et al., who demonstrated (following nephric duct-specific lim1 inactivation) that the nephric duct influences the formation, but not the initiation, of the Mullerian duct (Kobayashi et al., 2005). While the gonads were of normal size in the Gata3 mutant embryos, the testes, which were histologically normal (not shown), were often incompletely descended (Fig. 4B, arrowheads). In some embryos, a thin, atretic remnant of the nephric duct could be seen terminating abnormally within the body wall musculature (Fig. 4C–E, arrowheads). In e11.5 Gata3z/z embryos, bilaterally absent or abnormally shortened ducts were frequently observed (Lim et al., 2000). These shortened nephric ducts often appeared to initiate properly along the nephrogenic cord, but then veered and terminated into the lateral body wall (Table 2 and Fig. 4F, arrowhead).

Figure 4. Full penetrance of nephric duct extension defects in pharmacologically rescued Gata3 null mutant embryos.

e16.5 Gata3z/z females (A) and males (B) failed to form the definitive metanephric kidney and a uterus or vas deferens, respectively, while the testes (B, arrowheads) are histologically normal (data not shown). The majority of the pharmacologically rescued null embryos either lacked the nephric duct or had a thin, atretic duct that veered from its normal path of caudal extension in the nephrogenic cord to terminate abruptly in the lateral body wall (C = e14.5, D–E = e13.5, F = e11.5; arrowheads in C–F). Ov, ovaries; Ad, adrenal gland (arrowheads in A); UBl, urinary bladder; T, testis (arrowheads in B).

When the TgKE-G3 lines were bred onto the Gata3 null background, we observed variably rescued urogenital phenotypes that correlated best with the Tg expression levels amongst the multiple lines. In e16.5 Gata3z/z:TgH14 embryos, which expressed Tg-derived GATA-3 mRNA most abundantly (70% of diploid level), a full complement of genitourinary structures, including bilateral kidneys, ureters, Wolffian/nephric duct- and/or Mullerian duct-derived structures, was observed (Table 3; Fig. 5A, female, and 5B, male). Specifically, both kidneys appeared to be of normal size, with typical nephrogenic zones and underlying mature cortical tissue, when examined histologically (not shown), as observed in wild type and heterozygous e16.5 littermates (Fig. 3A–C). Thus, TgH14 completely rescued urogenital development in Gata3z/z embryos of both early (e11.5; Fig. 5C and Table 2) and late (e16.5; Fig. 5A, B and Table 3) gestational ages. Similarly, a second high expressing line H3, with Tg expression at approximately 50%, also rescued definitive nephrogenesis at late gestation (data not shown). Curiously, as in Gata3 heterozygous embryos, we also detected accessory UBs in midgestational compound mutant embryos of this line (Table 2).

Table 3.

Kidney and ureter phenotypes in e13.5 to e16.5 Gata3+/z, Gata3z/z:Tg and Gata3z/z embryos

| Genotype | Full rescue | Double ureter | Unilateral kidney | Hypoplastic kidney | Double kidney | ND on BW | Anephric |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TgHi:Gata3z/z | 5/5* | 1/5 | |||||

| TgInt:Gata3z/z | 2/9 | 6/9 | 7/9 | 1/9 | 2/9 | 1/9 | |

| TgLo:Gata3z/z | 3/3 | 3/3 | |||||

| Gata3z/z | 6/16 | 16/16 |

TgHi, H14; TgInt, G6 and H12; TgLo, B6. Full rescue = complete restoration of normal sized bilateral kidneys, ureters, and normally positioned gonads; Double ureter = unilaterally duplicated ureter; Unilateral kidney = unilateral renal agenesis; Hypoplastic kidney = abnormally smaller kidney; Double kidney = unilateral renal duplication; ND on BW = nephric duct remnant terminating on body wall; Anephric = lack of kidneys.

# affected/total # of embryos.

Figure 5. Urogenital rescue in Gata3 null mutants is dependent on KE-directed GATA-3 transgene expression level.

When bred to the most abundantly expressing KE-directed GATA-3 transgene (TgH14), urogenital development in e16.5 Gata3z/z females (A) and males (B) is fully rescued. Furthermore, the H14 transgene (70% of diploid expression) usually rescued the early (e11.5) renal haploinsufficiency (C). In a minority of examples, rescue with an intermediate level transgene (TgG6, expressing GATA-3 at 40% of wild type levels) led to defects at e11.5 (D; an atretic nephric duct with a discontinuous “floating” ureteric bud and a contralateral complete duct with an non-bifurcating bud). Complementation with TgG6 also led to aberrant kidney morphogenesis by e16.5: the kidneys were most often hypoplastic and in this instance, unilateral renal duplication with bilaterally shortened ureters that failed to contact the urinary bladder (E), while complementation with TgH12 (expressing 30% of diploid GATA-3 levels) often led to unilateral renal agenesis and hypoplasia (F).

Of the e13.5–16.5 Gata3z/z compound mutant embryos complemented with intermediate levels of GATA-3 expression (lines TgG6 and TgH12), the majority exhibited unilateral renal agenesis as well as hypoplastic metanephric kidneys (Fig. 5E and F and Table 3). Only one out of these 9 rescued mutants exhibited bilateral renal agenesis. Truncated ureters and, rarely, duplicated kidneys were observed in the Gata3z/z:Tg mutants that were rescued with intermediate transgenic GATA-3 levels (Fig. 5E and Table 3). At e11.5, Gata3z/z:TgG6-rescued mutants (40% of diploid GATA-3) displayed multiple abnormalities (e.g. discontinuous, “floating” ureteric buds associated with shortened nephric ducts; Fig. 5D). Careful histological examination of serial sections from one such embryo indicated an absence of ductal structures in the vicinity of the floating UB (not shown). This morphological aberration is reminiscent of the nephric duct degeneration observed in e11.5–e13.5 embryos after conditional inactivation of lim1 (in the nephric duct at e9.5), which results in progressive ductal atrophy (Kobayashi et al., 2005).

Finally, in the single low-expressing Tg line analyzed, renal agenesis in compound mutant Gata3z/z:Tg embryos was never reversed (Table 2). In these embryos, the renal developmental status at e16.5 resembled that observed in Gata3z/z embryos (Table 3), with vestigial rostral nephric ducts that were shortened and often extended laterally, abruptly terminating within the body wall.

In summary, complementation of the Gata3 germ line mutation by this graded series of KE-G3 Tg alleles resulted in either no (by low-expressing transgenic lines), partial (by intermediate-expressing transgenic lines) or complete (by high-expressing transgenic lines) restoration of metanephric development, indicating that there is a physiologically critical threshold of GATA-3 that is required for normal renal morphogenesis. Full restoration of metanephrogenesis was achieved by the highest-expressing transgenic line (70% of diploid levels), while lines expressing at lower (50% of diploid) levels only partially restored kidney development. In specific, the haploinsufficient mice exhibited nephric phenotypes that were indistinguishable from null mutant mice in which nephrogenesis was rescued by a transgene providing 50% of diploid abundance. Hence, from these data, we deduce that the severity of renal dysmorphia in rescued Gata3 null mutants declined with increasing transgenic GATA-3 abundance, and that the physiologically critical level of GATA-3 required for renal morphogenesis lies somewhere between 50% (as in heterozygotes or Gata3z/z:TgH3 embryos) and 70% (in Gata3z/z:TgH14 embryos). Additionally, the data demonstrate that the KE is sufficient for completion of metanephrogenesis in a rigorous in vivo assay.

Discussion

GATA3 haploinsufficiency in man and mice

GATA-3 is essential for renal morphogenesis since the loss-of-function mutation in humans and mice leads to kidney developmental defects, in addition to other developmental abnormalities (Lim et al., 2000; Van Esch et al., 2000). In patients, the loss of one GATA3 allele leads to the pathophysiological triad of parathyroid, otic and renal aberrations, the latter ranging widely in severity, from vesicoureteral reflux and renal hypoplasia or dysplasia to complete agenesis. Inactivation of both Gata3 alleles in mice leads to midembryonic demise (Pandolfi et al., 1995), and subsequent studies demonstrated that the cause of death was attributable to secondary cardiac failure as a consequence of a primary deficiency in catecholamine biosynthesis (Lim et al., 2000). After dietary supplementation with synthetic catechol intermediates, pharmacologically rescued late gestational Gata3 null embryos were noted to suffer developmental defects in multiple organ systems. Of immediate relevance here, it was apparent that a complete loss of Gata3 function led to a nearly complete failure to properly elaborate the inner ear (Karis et al., 2001; Lillevali et al., 2004), the parathyroid gland and the definitive kidney (Moriguchi et al., 2006), precisely the same organs affected in human HDR syndrome. Additionally, Gata3 null animals fail to generate either thymic or mammary glands (Moriguchi and Lim, unpublished observations), and more recently, hearing defects were reported in Gata3 heterozygous mutant animals (van der Wees et al., 2004). While we did not observe gross genitourinary defects in older Gata3+/z embryos or adults in the present study, early renal patterning defects were noted infrequently in midgestational heterozygotes, thus reflecting the highly variable kidney deficiencies that have been documented in HDR patients. Since we do not know what percentage of HDR patients have severe nephric aberrations in comparison to those that have very mild or no deficiencies, we can conservatively conclude that Gata3 haploinsufficiency likely results in no more severe nephric dysfunction in mice than in men.

Gata3 organ-specific dosage sensitivity

Haploinsufficiency has previously been reported to result in phenotypic manifestations in mice and humans (Seidman and Seidman, 2002). However, in only a few instances has it been elucidated how a two-fold reduction in a gene product would result in phenotypic presentation. The complexity of the problem is confounded further by gene modifiers and epigenetic events, which can expand the phenotypic variability of a haploinsufficiency syndrome or trait.

Here, we described the identification of a kidney enhancer element, located far 5' to the gene, that regulates Gata3 expression in the developing renal system, and the use of this enhancer to drive the expression of a GATA-3 transgene to rescue the metanephric agenesis observed in GATA-3-deficient embryos. While a previous study did not observe a correlation between reconstitution of nephrogenesis in rescued c-ret−/− mutants and transgene expression level using a heterologous kidney-specific promoter to rescue c-Ret expression (Srinivas et al., 1999), we found that the ability of the Gata3 KE-directed transgene to complement the renal defect in the Gata3 homozygous mutants is complete and related to its expression level, clearly demonstrating GATA-3 dosage sensitivity in renal development. Since we determined transgenic GATA-3 expression abundances at a single developmental time point (e16.5) in Gata3+/+:Tg kidneys, the caveats remain that the abundance of transgene expression may not completely mimic that of the endogenous gene throughout development, nor can we dismiss the possibility that there may be compensatory or autoregulatory mechanisms in play that lead to higher or lower than expected levels in the compound mutant transgenics or indeed, in the heterozygotes.

Despite these caveats, these data show that the success of renal morphogenic rescue correlates directly with GATA-3 levels and that the physiologically critical level is greater than 50% (the precise amount remains indeterminate) of diploid GATA-3 levels. Additionally, data from the analyses of other Gata3 hypomorphic alleles indicate that the critical threshold for proper development differs among the various GATA-3-expressing organs and tissues, and that renal morphogenesis is one of the more sensitive to perturbation (Moriguchi and Engel, unpublished observations). These observations are also consistent with clinical reports on HDR patients: for example, despite an absolute requirement for GATA-3 in murine and human T cell development, HDR patients are immunologically competent (Muroya et al., 2001). Since GATA-3 is not the only GATA family member expressed in T lymphocytes (Yamagata et al., 1997), GATA factor redundancy may partially explain the relatively intact adaptive immune function in HDR patients.

Gata3 transgenic mice may be useful for dissecting individual mechanistic steps leading to proper renal morphogenesis, which will shed light on the developmental events that have gone awry in individuals with duplicated ureters and kidneys or with renal dysplasia. The mystery behind GATA3 haploinsufficiency as it affects development of a specific subset of organ systems (kidneys, parathyroid glands and sensory neurons in the ear) remains both unresolved and intriguing. As we identify genetic regulatory domains that dictate GATA-3 expression as well as the downstream targets of GATA-3 in other anatomical sites using the experimental tools described here, we may be able to mechanistically decipher how a two-fold reduction in this transcription factor leads to dysgenesis of the renal and other organ systems, but does not affect the development of the numerous other tissues in which the same factor is vitally required. Similarly, detailed analysis of the 415 bp minimal KE should reveal possible direct regulators that control its activity. Since the minimal element contains more than a dozen potential binding sites for different transcription factors, detailed analysis (mutagenesis of individual binding sites followed by cotranfection studies, genetic epistasis tests for resolving which member of a given family of regulators is responsible for epithelium-specific, KE-specific activation) will require considerable effort before final experimental resolution.

The Gata3 locus is large

The data presented here show that Gata3 expression in the developing urogenital system can be fully complemented by an enhancer element lying 113 kbp 5’ to the GATA-3 translation initiation site. This characterization as a “distant” localization, however, may be deceptively overstated: we have now surveyed > 1.5 Mbp surrounding the Gata3 locus (Moriguchi, Kuroha, Rao, Lim and Engel, unpublished) using the BAC-trap strategy (Khandekar et al., 2004), and have found that numerous enhancers controlling Gata3 spatiotemporal activity that are yet to be discovered lie even further (i.e. more than 500 kbp) from the structural gene. Within the limited context of studies that have examined the transcriptional control over regulatory genes (e.g. those encoding transcription factors, signaling molecules and their receptors), this noteworthy fact is nonetheless no longer surprising: enhancers lying > 1 Mbp from the Shh and Sox9 structural genes have been clearly documented (Bishop et al., 2000; Lettice et al., 2003). How or why some mammalian patterning genes achieve such remarkably accurate developmental specificity from such vast genomic distances, often bypassing activation of intervening transcription units, is a fundamental conundrum that is yet to be resolved or even seriously addressed.

Materials and Methods

Plasmid constructions

To rescue genomic sequences from mouse Gata3 YACs B143 and B157, we performed end fragment rescue as described previously (Lakshmanan et al., 1998). Briefly, EcoRI-digested YAC DNA was self-ligated and transformed into E. coli. A 9.2 kbp Gata3 genomic DNA fragment was retrieved from the B143 end fragment-rescued plasmid and subcloned into pG3lacZ (previously named –308placZ), consisting of the Gata3 proximal minimal promoter at –1310 bp, with respect to the Gata3 translational start site, driving the lacZ reporter gene (Lieuw et al., 1997). Smaller DNA fragments of the 9.2 kbp test insert were analyzed for KE activity by exploiting unique restriction sites in the parental fragment and then subcloning those fragments into pG3lacZ (Fig. 1B). PCR-assisted cloning was used to generate lacZ expression vectors containing single or triplicated copies of the conserved 415 bp CSE. The fidelity of PCR amplification was verified by sequencing.

To generate kidney-specific expression of GATA-3 or eGFP, DNA encoding either protein was used to replace the lacZ gene in pG3lacZ. A 1.3 kbp SwaI/HindIII Gata3 KE, which was shown to retain kidney enhancer activity in transgenic expression founder assays, was used to direct transgenic expression of both the GATA3 and eGFP DNAs.

Transgenic mice

To generate transgenic animals, expression constructs were microinjected into CD1 fertilized oocytes following standard protocols (Nagy et al., 2003). To identify transgenic animals, DNAs from yolk sac or tail snip of founder animals were used for genotyping by PCR or Southern blotting for the presence of transgene (lacZ, eGFP or GATA-3). For F0 analyses, embryos were harvested from foster mothers at appropriate gestational days, stained with X-gal and processed for photography, as previously described (Lieuw et al., 1997). For stable lines expressing KE-directed GATA-3, F2 and subsequent generations of progeny (continually backcrossed onto a CD1 outbred background) were examined for Tg copy number and Tg-derived transcript accumulation. The generation and characterization of Gata3/lacZ heterozygous (Gata3+/Z) mice was previously reported (Hendriks et al., 1999; van Doorninck et al., 1999). PCR genotyping of progeny from Gata3+/Z intercrosses was performed as described (Kaufman et al., 2003). For kidney-specific rescue, Gata3+/Z:TgKE-G3 animals were mated with Gata3+/z mice and the dams were given ad libum drinking water containing catechol intermediates, as described previously (Kaufman et al., 2003; Lim et al., 2000). Embryos from timed pregnancies or neonates were processed for X-gal staining followed by photography and genotyping by PCR.

Semi-quantitative RT-PCR

Semi-quantitative RT-PCR was performed as previously described (Tanimoto et al., 2000). Total RNA was isolated from tissues using ISOGEN (Nippon Gene). First strand cDNA was synthesized using 1 μg of total RNA and Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) in a 20 μl reaction volume. For template-limiting PCR, 1 μl of cDNA was serially diluted two-fold and amplified for 35 cycles. Amplified products were fractionated on polyacrylamide gels and quantified using a phosphoimager (Molecular Dynamics). PCR primers used were: HPRT [5' gcttgctggtgaaaaggac 3’ (S) and 5' caacttgcgctcatcttagg 3’ (AS)], GATA-3 [5' atcaagcccaagcgaaggct 3’ (S) and 5' gaatgcagacaccacctcgagctcc 3’ (AS, specific for endogenous mRNA) or 5’ ccgcctacttgtcatcgtcgtccttgtagtc 3’ (AS, transgene-specific).

Immunofluorescence staining

Anti-eGFP and anti-β-galactosidase immunofluroescence was performed essentially as described (Khandekar et al., 2004).

Supplementary Material

Comparison of temporal activation of the lacZ reporter gene driven by the 1.3 kbp KE in a stable transgenic line (D-F) and the Gata3 lacZ knock-in allele (A-C) in X-gal stained embryos with similar somite number at e9.0 (A and D), e9.5 (B and E) or e10.5 (C and F) of embryogenesis, when the nephric duct is formed.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Xia Jiang, Kimberly Lane, David McPhee, Weimin Song and Misti Thompson for outstanding technical assistance. We are grateful to past and present lab members, in particular Melin Khandekar, as well as Yashpal Kanwar (Northwestern University) for assistance. Finally, we thank the staff in the Microscopy and Image Analysis Laboratory at the University of Michigan for their technical and photographic advice. This work was supported by research grants from the NIH (GM28896; J.D.E.) and the National Kidney Foundation (K.-C. L.) and in part by the NIH through the University of Michigan's Cancer Center Support Grant (CA46592).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Literature Cited

- Bishop CE, Whitworth DJ, Qin Y, Agoulnik AI, Agoulnik IU, Harrison WR, Behringer RR, Overbeek PA. A transgenic insertion upstream of sox9 is associated with dominant XX sex reversal in the mouse. Nature Genetics. 2000;26:490–4. doi: 10.1038/82652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchard M, Souabni A, Mandler M, Neubuser A, Busslinger M. Nephric lineage specification by Pax2 and Pax8. Genes and Development. 2002;16:2958–70. doi: 10.1101/gad.240102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies JA, Fisher CE. Genes and proteins in renal development. Experimental Nephrology. 2002;10:102–13. doi: 10.1159/000049905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dressler G. Tubulogenesis in the developing mammalian kidney. Trends Cell Biol. 2002;12:390–5. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(02)02334-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George KM, Leonard MW, Roth ME, Lieuw KH, Kioussis D, Grosveld F, Engel JD. Embryonic expression and cloning of the murine GATA-3 gene. Development. 1994;120:2673–86. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.9.2673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert SF. Developmental Biology. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks RW, Nawijn MC, Engel JD, van Doorninck H, Grosveld F, Karis A. Expression of the transcription factor GATA-3 is required for the development of the earliest T cell progenitors and correlates with stages of cellular proliferation in the thymus. European Journal of Immunology. 1999;29:1912–8. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199906)29:06<1912::AID-IMMU1912>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karis A, Pata I, van Doorninck JH, Grosveld F, de Zeeuw CI, de Caprona D, Fritzsch B. Transcription factor GATA-3 alters pathway selection of olivocochlear neurons and affects morphogenesis of the ear. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2001;429:615–30. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20010122)429:4<615::aid-cne8>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman CK, Zhou P, Pasolli HA, Rendl M, Bolotin D, Lim KC, Dai X, Alegre ML, Fuchs E. GATA-3: an unexpected regulator of cell lineage determination in skin. Genes and Development. 2003;17:2108–22. doi: 10.1101/gad.1115203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khandekar M, Suzuki N, Lewton J, Yamamoto M, Engel JD. Multiple, distant Gata2 enhancers specify temporally and tissue-specific patterning in the developing urogenital system. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2004;24:10263–76. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.23.10263-10276.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko LJ, Engel JD. DNA-binding specificities of the GATA transcription factor family. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1993;13:4011–22. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.7.4011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko LJ, Yamamoto M, Leonard MW, George KM, Ting P, Engel JD. Murine and human T-lymphocyte GATA-3 factors mediate transcription through a cis-regulatory element within the human T-cell receptor delta gene enhancer. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1991;11:2778–84. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.5.2778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi A, Kwan KM, Carroll TJ, McMahon AP, Mendelsohn CL, Behringer RR. Distinct and sequential tissue-specific activities of the LIM-class homeobox gene Lim1 for tubular morphogenesis during kidney development. Development. 2005;132:2809–23. doi: 10.1242/dev.01858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuure S, Vuolteenaho R, Vainio S. Kidney morphogenesis: cellular and molecular regulation. Mechanisms of Development. 2000;92:31–45. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(99)00323-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labastie MC, Catala M, Gregoire JM, Peault B. The GATA-3 gene is expressed during human kidney embryogenesis. Kidney International. 1995;47:1597–603. doi: 10.1038/ki.1995.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakshmanan G, Lieuw KH, Grosveld F, Engel JD. Partial rescue of GATA-3 by yeast artificial chromosome transgenes. Developmental Biology. 1998;204:451–63. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.8991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakshmanan G, Lieuw KH, Lim KC, Gu Y, Grosveld F, Engel JD, Karis A. Localization of distant urogenital system-, central nervous system-, and endocardium-specific transcriptional regulatory elements in the GATA-3 locus. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1999;19:1558–68. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.2.1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lettice LA, Heaney SJ, Purdie LA, Li L, de Beer P, Oostra BA, Goode D, Elgar G, Hill RE, de Graaff E. A long-range Shh enhancer regulates expression in the developing limb and fin and is associated with preaxial polydactyly. Human Molecular Genetics. 2003;12:1725–35. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieuw KH, Li G, Zhou Y, Grosveld F, Engel JD. Temporal and spatial control of murine GATA-3 transcription by promoter- proximal regulatory elements. Developmental Biology. 1997;188:1–16. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillevali K, Matilainen T, Karis A, Salminen M. Partially overlapping expression of Gata2 and Gata3 during inner ear development. Developmental Dynamics. 2004;231:775–81. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim KC, Lakshmanan G, Crawford SE, Gu Y, Grosveld F, Engel JD. Gata3 loss leads to embryonic lethality due to noradrenaline deficiency of the sympathetic nervous system. Nature Genetics. 2000;25:209–12. doi: 10.1038/76080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merika M, Orkin SH. DNA-binding specificity of GATA family transcription factors. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1993;13:3999–4010. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.7.3999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriguchi T, Takako N, Hamada M, Maeda A, Fujioka Y, Kuroha T, Huber RE, Hasegawa SL, Rao A, Yamamoto M, Takahashi S, Lim K-C, Engel JD. Gata3 participates in a complex transcriptional feedback network to regulate sympathoadrenal differentiation. Development. 2006;133 doi: 10.1242/dev.02553. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muroya K, Hasegawa T, Ito Y, Nagai T, Isotani H, Iwata Y, Yamamoto K, Fujimoto S, Seishu S, Fukushima Y, et al. GATA3 abnormalities and the phenotypic spectrum of HDR syndrome. Journal of Medical Genetics. 2001;38:374–80. doi: 10.1136/jmg.38.6.374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy A, Gertsennstein M, Vintersten K, Behringer RR. Manipulating the mouse embryo: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pandolfi PP, Roth ME, Karis A, Leonard MW, Dzierzak E, Grosveld FG, Engel JD, Lindenbaum MH. Targeted disruption of the GATA3 gene causes severe abnormalities in the nervous system and in fetal liver haematopoiesis. Nature Genetics. 1995;11:40–4. doi: 10.1038/ng0995-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sainio K, Suvanto P, Davies J, Wartiovaara J, Wartiovaara K, Saarma M, Arumae U, Meng X, Lindahl M, Pachnis V, et al. Glial-cell-line-derived neurotrophic factor is required for bud initiation from ureteric epithelium. Development. 1997;124:4077–87. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.20.4077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidman JG, Seidman C. Transcription factor haploinsufficiency: when half a loaf is not enough. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2002;109:451–5. doi: 10.1172/JCI15043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shawlot W, Behringer R. Requirement for Lim1 in head-organizer function. Nature. 1995;374:425–430. doi: 10.1038/374425a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivas S, Wu Z, Chen CM, D'Agati V, Costantini F. Dominant effects of RET receptor misexpression and ligand-independent RET signaling on ureteric bud development. Development. 1999;126:1375–86. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.7.1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanimoto K, Liu Q, Grosveld F, Bungert J, Engel JD. Context-dependent EKLF responsiveness defines the developmental specificity of the human epsilon-globin gene in erythroid cells of YAC transgenic mice. Genes and Development. 2000;14:2778–94. doi: 10.1101/gad.822500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ting CN, Olson MC, Barton KP, Leiden JM. Transcription factor GATA-3 is required for development of the T-cell lineage. Nature. 1996;384:474–8. doi: 10.1038/384474a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang TE, Shawlot W, Kinder SJ, Kobayashi A, Kwan KM, Schughart K, Kania A, Jessell TM, Behringer RR, Tam PP. Lim1 activity is required for intermediate mesoderm differentiation in the mouse embryo. Developmental Biology. 2000;223:77–90. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Wees J, van Looij MA, de Ruiter MM, Elias H, van der Burg H, Liem SS, Kurek D, Engel JD, Karis A, van Zanten BG, et al. Hearing loss following Gata3 haploinsufficiency is caused by cochlear disorder. Neurobiol Dis. 2004;16:169–78. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Doorninck JH, van Der Wees J, Karis A, Goedknegt E, Engel JD, Coesmans M, Rutteman M, Grosveld F, De Zeeuw CI. GATA-3 is involved in the development of serotonergic neurons in the caudal raphe nuclei. Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;19:RC12. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-12-j0002.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Esch H, Groenen P, Nesbit MA, Schuffenhauer S, Lichtner P, Vanderlinden G, Harding B, Beetz R, Bilous RW, Holdaway I, et al. GATA3 haplo-insufficiency causes human HDR syndrome. Nature. 2000;406:419–22. doi: 10.1038/35019088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamagata T, Nishida J, Sakai R, Tanaka T, Yazaki Y, Hirai H. Of the GATA-binding proteins, only GATA-4 selectively regulates the human IL-5 gene promoter in IL-5 producing cells which express multiple GATA-binding proteins. Leukemia. 1997;11(Suppl 3):501–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto M, Ko LJ, Leonard MW, Beug H, Orkin SH, Engel JD. Activity and tissue-specific expression of the transcription factor NF-E1 [GATA] multigene family. Genes and Development. 1990;4:1650–62. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.10.1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, McMahon AP, Valerius MT. Recent genetic studies of mouse kidney development. Current Opinion in Genetics and Development. 2004;14:550–7. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2004.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng W, Flavell RA. The transcription factor GATA-3 is necessary and sufficient for Th2 cytokine gene expression in CD4 T cells. Cell. 1997;89:587–596. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80240-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Lim KC, Onodera K, Takahashi S, Ohta J, Minegishi N, Tsai FY, Orkin SH, Yamamoto M, Engel JD. Rescue of the embryonic lethal hematopoietic defect reveals a critical role for GATA-2 in urogenital development. EMBO Journal. 1998;17:6689–6700. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.22.6689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Comparison of temporal activation of the lacZ reporter gene driven by the 1.3 kbp KE in a stable transgenic line (D-F) and the Gata3 lacZ knock-in allele (A-C) in X-gal stained embryos with similar somite number at e9.0 (A and D), e9.5 (B and E) or e10.5 (C and F) of embryogenesis, when the nephric duct is formed.