Abstract

Using a representative sample of over 900 low-income urban families from the Three-City Study, analyses assessed whether maternal human capital characteristics moderate relationships between mothers' welfare and employment experiences and young adolescents' well-being. Results indicate synergistic effects whereby greater maternal education and literacy skills enhanced positive links between mothers' new or sustained employment and improvements in adolescent cognitive and psychosocial functioning. Greater human capital also enhanced the negative links between loss of maternal employment and adolescent functioning. Mothers' entrances onto welfare appeared protective for adolescents of mothers with little education but predicted decreased psychosocial functioning among teens of more educated mothers. Results suggest that maternal human capital characteristics may alter the payback of welfare and work experiences for low-income families.

Keywords: welfare reform, poverty, maternal employment, adolescent functioning, human capital

Rates of both welfare receipt and maternal employment rose consistently over most of the second half of the 20th century. These parallel increases indicated a divergence in the economic paths of more- versus less-advantaged families. More educated and married families experienced higher rates of maternal employment, while less advantaged and unmarried parents increased their reliance on welfare and public supports. However, in the mid 1990's a confluence of substantive social policy changes and sustained economic expansion helped to alter trajectories for low-income families. The 1996 Personal Responsibility and Work Reconciliation Act (PRWORA), commonly known as welfare reform, instituted time limits, work requirements, increased use of sanctions, and a host of other changes. Collectively these policies sought to move families off welfare and discourage entries onto welfare, and to move poor parents into active and sustained involvement in the work force. Coinciding expansions in both the U.S. economy and in government supports for low-income working families (e.g., the Earned Income Tax Credit, expansion of child health insurance programs) helped to make employment more profitable for low-wage parents. In the second half of the 1990's the demographic trends shifted markedly, with a greater than 50% reduction in the welfare rolls between 1994 and 2000, and a nearly 20% rise in maternal employment among unmarried mothers (Blank & Haskins, 2002; Mishel, Berstein, & Boushey, 2003).

Policy analysts predicted that these substantial social policy and behavioral changes would exert significant influence on the development of low-income children. As parents moved onto and then up the employment ladder, greater economic independence and stability should follow, thereby improving family processes. As developmental and economic conceptual models would argue, greater economic assets could increase cognitively stimulating resources and activities and enhance the availability of role models of economic success, motivating youth to perform better in school (Becker, 1991; Wilson, 1996). Similarly, economic resources and stability could improve parental functioning and family processes, hence decreasing children's proclivity towards problem behaviors and psychological distress (Conger, Reuter, & Conger, 2000; McLoyd, 1998). Alternately, increased economic insecurity and instability could lead to declines in these arenas of family functioning and inhibit children's developmental trajectories.

Yet research is just beginning to unpack the complicated patterns of family and child functioning in the wake of welfare reform. Scholars note that the myriad policy and economic changes have led to an array of reactions in families' economic behaviors which tend not to have clear, unilateral effects on child well-being. Rather, many concur that some children, under some contexts, have likely experienced improvements in well-being following welfare reform, whereas other children have floundered (Duncan & Chase-Lansdale, 2001; Knitzer, Yoshikawa, Cauthen, & Aber, 2000). One central factor that may help to distinguish trajectories is the level of human capital, or skills and education, which parents bring to the economic marketplace under the altered environment created by PRWORA policies (Becker, 1991; Harris, 1996). Parental skills can influence the economic resources parents garner as well as the familial environments and parenting behaviors that they provide to their children. In short, parental human capital may influence both proximal and more distal environments that are provided to children. The goal of this paper is to assess whether mothers' employment and welfare experiences in the wake of federal welfare reform are linked to adolescent well-being differentially, depending upon the skills and resources that mothers bring to their economic situations.

Within this research, we focus specifically on the trajectories of young adolescents, a developmental group which has received somewhat limited attention in recent research on welfare and employment but which has raised concerns in recent literature (see below). Early adolescence is a central developmental transition period during which young people face a plethora of changes in their relationships, behaviors, and academics. Across these transitions, adolescents often view their parents and family experiences as models for their own behavior and development of goals (Feldman & Elliott, 1990). In turn, adolescents' experiences may influence both how they learn and achieve in school, and how they function behaviorally and psychologically.

Literature Review

Recent decades have seen an increase in scholarly attention devoted to studying links between maternal employment and welfare experiences and adolescent development. In research conducted prior to PRWORA linking family welfare receipt or state welfare funding with adolescent functioning, results are mixed, with both positive and negative relationships found between welfare and school outcomes, engagement in problem behaviors, and nonmarital childbearing (see Lohman, Pittman, Coley, & Chase-Lansdale, 2004 and Moffitt, 1998 for overviews). Past findings on maternal employment are somewhat more consistent. Research conducted primarily in middle-class and married-parent families generally finds few effects of maternal employment on children's well-being, although findings are somewhat more consistently positive for older children and for low-income children, and concerning cognitive outcomes (Bianchi, 2000; Hoffman & Youngblade, 1999). However, other research focused on employment transitions has found parental employment loss to predict poor psychosocial functioning for adolescents, particularly in the realms of psychological distress and problem behaviors (Elder, 1974; McLoyd, Jayartne, Ceballo, & Borquez, 1994; see also Conger, et al., 2000; Wilson, 1996).

A handful of studies following families as they traversed welfare reform have also found rather minimal and conflicting findings regarding links between mothers' welfare and work experiences and adolescent development. Two longitudinal survey studies tracking sizable samples of families in the years after PRWORA have found similar small positive links between mothers' movements from welfare to work and adolescent functioning. Results from the Michigan Women's Employment Study (WES) found that adolescents were less likely to be expelled or suspended from school when mothers moved from welfare-reliant to a combination of employment and welfare (Dunifon & Kalil, 2003). Exits from employment were not considered. Chase-Lansdale and colleagues (Chase-Lansdale et al., 2003) modeled mothers' welfare and employment transitions independently, using data from the Three-City Study. This research found that transitions into employment predicted improvement in adolescents' psychological functioning. Transitions off welfare predicted improved literacy skills and decreased drug and alcohol use, whereas moving onto welfare predicted declines in the same areas. In short, survey results suggest some small improvements in the functioning of low-income adolescents as their mothers move off welfare or into employment.

In contrast, experimental assessments of welfare reform programs in the U.S. and Canada that preceded federal welfare reform have reported contradictory findings regarding adolescent functioning. Initial analyses found that families assigned to the experimental programs with new welfare rules (many of which encompassed rules similar to those instituted in the 1996 federal reforms, albeit in a different policy environment) typically experienced greater maternal employment and less welfare use in comparison to control group families. However, adolescents in the experimental groups showed more problematic behaviors and school performance than control group adolescents (Gennetian, et al. 2004; Morris, Huston, Duncan, Crosby, & Bos, 2001).

Although these studies focused explicitly on adolescent development in relation to parental employment and welfare experiences, they paid scant attention to the important questions of for whom, or under what conditions, welfare and employment experiences are influential. One central moderator that has concerned scholars is the human capital that parents bring to their economic and familial rolls. Human capital characteristics—education and job skills—are key predictors of low-income women's stability in the job market and use of welfare (Danziger, Kalil, & Anderson; 2000; Harris, 1996). Substantial research also notes the consistent benefit of greater parental education and skills for numerous areas of child development (Becker, 1991). More educated and skilled mothers are, on average, more likely to be employed in more prestigious, high paying, and satisfying jobs, and to provide greater cognitive stimulation and emotional support to their children. All of these economic and parenting resources promote greater cognitive and psychosocial development among children (Harris, 1996; Menaghan & Parcel, 1994; 1995). Moreover, a handful of studies have argued that parental education and skills may interact in important ways with parental employment and welfare experiences.

One argument purports that higher education leads to greater success in the job market, and hence may enhance positive effects of employment. For example, using CPS data from pre-PRWORA, Moffitt (1999) found that state-level welfare reform waivers decreased welfare participation and increased employment but led to increased earnings only among women with a high school degree. Similarly, using longitudinal CPS data, Bennett, Lu, & Song (2002) found that among poor families, only parents with some education beyond high school experienced increased incomes following welfare reform, whereas incomes declined among parents with less than a high school degree. Cancian and Meyer (2004) argue that as welfare reform evolves, less educated and job-ready mothers are being moved off of welfare, with declining economic payback and perhaps increased stress and instability.

Although these papers did not link changes in parental welfare and employment to children's development, they suggest the possibility for such a link. Namely, parents with greater education and skills could gain more (economically and psychologically) in response to movements off welfare and into employment, thereby improving the developmental success of their children (Becker, 1991; Conger, Rueter, & Conger, 2002). In short, this argues for a synergistic effect (Rutter, 1993), whereby families with the greatest human capital resources have the most to gain from enhanced connection to the labor force—they may access higher pay and more stimulating and supportive jobs, increasing the resources available for their children (Menaghan & Parcel, 1994; 1995; Raver, 2003). Similarly, low education and skills may add to the risks of unemployment and welfare dependence in a cumulative fashion as posited by cumulative stress theories of development (Sameroff & Chandler, 1975; Evans, 2004).

A contrasting argument is the “risk-buffering” perspective proposed by Yoshikawa (1999) who reported that longer welfare receipt histories predicted greater cognitive skills in children of more highly educated mothers, whereas staying on welfare appeared detrimental for children of less educated mothers. Further analyses of experimental state welfare reform programs find similar results, suggesting that the programs that help to move women off welfare and into employment benefit children of less educated mothers more than those in families with greater human capital. More at-risk mothers, with longer welfare histories, less education, and less employment experience, received little net income gain from the welfare reform programs. Yet children and adolescents in these families showed better behavioral and school outcomes than their peers in lower-risk families (Gennetian & Miller, 2002; Morris, Bloom, Klemple, & Hendra, 2003). One possible explanation is that children of more disadvantaged and low-skilled mothers had the most to gain from policy changes that moved their families out of long-term dependency and into employment with continued supports. Even if these employment opportunities do not result in significant economic gain, they may improve mothers' psychological functioning and provide important new models and opportunities for children. Other research using a subset of the experimental program data has found curvilinear results, with positive effects (improved school success and decreased behavior problems) of welfare reform programs for children from families with moderate levels of human capital and disadvantage, and detrimental effects on children facing the most disadvantage (Yoshikawa, Magnuson, Bos, & Hsueh, 2003).

In all of these programs, the moderating effects of maternal education and skills have not be explicitly addressed net of other factors; similarly, the influence of welfare versus work transitions have not been independently assessed. As suggested in developmental research on employment and income loss, transitions both into and out of employment and welfare may be differentially linked to adolescent well-being depending on the human capital skills that mothers bring to their parenting and economic activities.

Research Questions

Overall, recent research supports no firm conclusions concerning the influence of maternal welfare and employment experiences on low-income adolescents in the policy and economic context following welfare reform. Although inconsistent across studies, earlier research suggests that families' human capital resources may influence the manner in which families react to new economic opportunities and moderate their effects on adolescents' developmental trajectories. In the current analyses, we assess whether mothers' educational attainment and literacy skills moderate links between welfare and employment patterns and adolescent developmental trajectories. These analyses extend initial findings from the Three-City Study noted above (Chase-Lansdale et al., 2003) to provide a more nuanced view of the development of low-income adolescents in the current policy environment by discerning under which family contexts mothers' welfare and work experiences may best support or impede healthy adolescent trajectories.

Methods

Sampling and Data Collection

Data are drawn from waves one and two of Welfare, Children, and Families: A Three-City Study, a longitudinal, multi-method study of the well-being of children and families in the wake of federal welfare reform. Among other components, the Three-City Study includes a household-based, stratified random-sample survey with over 2,400 low-income children and their mothers in low-income neighborhoods in Boston, Chicago, and San Antonio. In 1999, over 40,000 households in randomly selected low-income neighborhoods (93% of block groups selected for sampling had a 20% or higher poverty rate) were screened, with a screening response rate of 90 percent. In selected families with household incomes of 200% or less of the poverty line and a child between the ages of 0 to 4 or 10 to 14 years, interviewers randomly selected one focal child and invited the focal child and his or her primary female caregiver to participate. Eighty-three percent of selected families agreed to participate, resulting in an overall response rate of 74 percent. A second wave of interviews was completed with approximately 88 percent of these families 16 months later, on average, in 2001. For further sampling details see Winston et al., (1999). To put the study into historical context, the data were collected approximately 3 to 5 years after the passage of PRWORA, and five to ten years after many states had implemented waivers to alter their welfare policies.

In each family, focal children and caregivers (referred to as “mothers” as over 90% of the caregivers were biological mothers) participated in separate in-home interviews. Sections of the adolescent and mother interviews which covered particularly sensitive topics (e.g., delinquency, psychological distress) were conducted using Audio Computer Assisted Self Interviewing (ACASI), which has been shown to increase the validity of reporting on sensitive topics (Turner et al., 1998). Interviews were translated (and verified with back-translations) into Spanish, and this version was used by approximately 2% of adolescents and 12% of mothers who reported their current primary language was Spanish. All respondents were paid for their participation in the study.

This paper focuses on the young adolescents from the Three-City Study who participated at both waves and had nonmissing data on the central predictor variables (unweighted n = 916). Attrition analyses between the included sample and the sample excluded due to nonparticipation in wave 2 (n = 123; 10.7%) or to missing maternal welfare and employment data (n = 119, 10.2%) found that families included in the analyses contained mothers who were significantly older, had fewer minor children in the household, and were more likely to be biological mothers in comparison to families who were excluded. These characteristics were controlled for in multivariate analyses. Furthermore, selection is addressed statistically through the use of probability weights in all analyses, which adjust for the sampling strata as well as for nonresponse, making the sample representative of adolescents in low-income families living in low-income neighborhoods in the three cities. Weighted n's vary slightly across analyses due to missing data on the dependent variables, and range from 794 to 823.

Measures

Welfare and employment variables

At each interview, mothers used a calendar format to report on their welfare receipt, employment status, and employment hours for each of the previous 24 months. Welfare was defined as TANF, and did not include other social programs such as SSI. In the current analyses, definitions of welfare and employment were created to provide the most temporally meaningful window and account for both history as well as recency. At each wave, mothers' welfare and employment experiences were considered over the previous 11 months, chosen both to limit concerns over recall accuracy and because 11 months was the shortest time period between the two waves in the survey sample. At each wave, mothers were coded as “on welfare” if they reported welfare receipt in the majority of the past 11 months including at least 2 of the past 3 months. The dichotomous on or off welfare variables were then combined across the two waves into a set of exclusive categories: Stable Welfare (on welfare at wave 1 and wave 2), Into Welfare (off welfare wave 1; on welfare wave 2), Off Welfare (on welfare wave 1; off welfare wave 2), and Never Welfare (off welfare both waves). Similarly, at each wave mothers were coded as “employed” if they reported paid employment for 20 hours or more per week in the majority of the past 11 months including at least 2 of the past 3 months. Combining data from the two waves created the exclusive categories of Stable Employment, Into Employment, Out of Employment, and Never Employment. In contrast to simple point-in-time assessments of welfare and employment, these definitions account for families' predominant experiences over the 11 months preceding each interview. In both previous published analyses (Chase-Lansdale et al., 2003) and additional modeling conducted for this paper (see Results), alternate definitions of employment and welfare were modeled, including long- and short-term and any and full-time employment. Results were relatively robust across definitions.

Maternal human capital

Two measures assess mothers' human capital: maternal education and cognitive skills. Mothers' highest level of education was coded into three categories: Less than High School, High School or GED (omitted), and More than High School. The wave 1 measure of maternal education was used, as few mothers increased their educational attainment between waves. In addition to completed education, mothers' cognitive skills were assessed in order to capture skills that women bring to the marketplace and to parenting. During wave 2, mothers' literacy and verbal skills were directly assessed using the Letter-Word Identification scale from the Woodcock-Johnson Psycho-Educational Battery- Revised Edition (Woodcock and Johnson, 1989; 1990; Woodcock and Munoz-Sandoval, 1996). Scores were standardized using the norms developed by the authors.

Adolescent outcomes

Information on adolescent functioning was obtained through three different sources in order to ease concerns over shared method variance and reporter error. Measures were focused on three aspects of adolescent well-being that are central to healthy functioning during adolescence and are also key predictors of successful adaptation in adulthood: cognitive achievement, psychological functioning, and behavioral functioning. All measures were collected at waves 1 and 2. Cognitive achievement was directly assessed through the administration of standardized achievement tests to each adolescent. The Applied Problems and Letter-Word Identification subscales from the Woodcock-Johnson Psycho-Educational Battery-Revised Edition assessed Quantitative Skills and Literacy Skills respectively (Woodcock and Johnson, 1989; 1990; Woodcock and Munoz-Sandoval, 1996). Scores were standardized using the norms developed by the authors.

Psychological and behavioral functioning was reported by both mothers and adolescents. Adolescents reported on their experiences of Psychological Distress through a shortened version of the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI-18, Derogatis, 2000), which assesses symptoms of depression, somatization, and anxiety. Respondents were asked 18 items about their experiences in the past week, using a 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely) scale. All items were averaged and a natural log taken to help correct skewness, with higher scores indicating a greater incidence of psychological distress (αT1=.89, αT2=.92). The BSI-18 has shown high internal and test-retest reliability as well as discriminant reliability (Derogatis, 2000). Adolescents also reported on their engagement in problem behaviors through a series of 17 items adapted from the National Longitudinal Study of Youth (NLSY; Borus, Carpenter, Crowley, & Daymont, 1982) and the Youth Deviance Scale (Gold, 1970), previously used in research with low-income minority adolescents (Coley & Chase-Lansdale, 2000; Pittman & Chase-Lansdale, 2001). Items focused on engagement within the past year in three areas of problem behavior, including serious delinquency, drug and alcohol use, and school problems, assessed on a 1 (never) to 4 (often) scale. Items were standardized, averaged, and logged to create a total score of Delinquency (αT1=.71, αT2=.84).

Mothers responded to the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), a well-validated, 100-item measure which assesses emotional and behavioral problems such as depression, anxiety, aggression, and delinquency (Achenbach, 1992). The CBCL creates two primary subscales focused on Internalizing Problems (e.g., depression, withdrawal, and anxiety αT1=.87, αT2=.88) and Externalizing Problems (e.g., aggression and delinquency αT1=.89, αT2=.90). Categorical variables designating scores at or above the borderline/clinical cutoff points (84th percentile) were used to signal the presence of serious emotional or behavior problems which are likely to require psychological services.

To assess the ethnic equivalence of the central developmental measures and assure adequate measurement properties across the two primary ethnic groups, internal reliabilities were also assessed separately for African American (AA) and Hispanic (H) adolescents. Results indicate similar internal reliabilities across these two groups for psychological distress (αT1AA=.88, αT2AA=.90, αT1H=.90, αT2H=.94), delinquency(αT1AA=.65, αT2AA=.84, αT1H=.70, αT2H=.89), internalizing(αT1AA=.81, αT2AA=.84, αT1H=.86, αT2H=.88), and externalizing(αT1AA=.86, αT2AA=.90, αT1H=.88, αT2H=.89).

Demographic characteristics

Mothers reported on numerous characteristics of their adolescents, themselves, and their families. Because such demographic and human capital characteristics often select people into welfare and employment experiences and may mask the relationship between welfare or employment and adolescent well-being, these characteristics are used as covariates in the multivariate analyses. All characteristics were measured at the wave 1 survey, with time-varying factors assessed again at wave 2. Adolescents' gender was coded as male with female omitted, and age was coded in years. Race/ethnicity is coded into three categories, Hispanic of any race (omitted), non-Hispanic Black, and non-Hispanic White/Other. Maternal age was coded in years, and marital status was captured using dummy variables denoting cohabitation and marriage, with single omitted. An additional dummy variable indicated whether the caregiver was the biological mother of the focal child. The number of minor children in the household was coded as a continuous variable. Mothers also reported whether English was their first language, and their city of residence was coded as Boston or Chicago, with San Antonio as the omitted category. Household income was summed for all household members from all sources, including food stamps. Missing control variables were imputed using median imputation, and a dummy variable was included in analyses to indicate imputation.

Analysis Plan

Main effects models

Ordinary least squares (OLS) regression analyses with robust standard errors to adjust for sample clustering were used to estimate how mothers' welfare and employment experiences and interactions between welfare and employment experiences and maternal human capital characteristics are associated with adolescents' developmental trajectories. The base regression model is the following:

Adolescent Outcome2i= B0 + B1OntoWel12i + B2OffWel12i + B3StableWel12i + B4IntoEmp12i + B5OutOfEmp12i + B6StableEmp12i + B7Adolescent Outcome1i + B8Control Variables1 + εi

The first three independent variables in the model are those measuring welfare transitions and stability, and the coefficients on each depict the influence of that welfare pattern on changes in adolescent outcomes in comparison to the omitted category of being off welfare at both waves. Similarly, the next three variables assess the association of each employment pattern on changes in adolescent outcomes in comparison to the omitted category of being not employed at both waves. Adjusted Wald posthoc tests were used to assess differences between pairs of welfare patterns included in the model (e.g., to assess whether stable welfare was different from off welfare in relation to changes in adolescent outcomes) and between employment patterns (e.g., into employment versus out of employment). This model form, known as a lagged regression or autoregressive model, controls for the adolescent outcome from wave 1 in predicting the same outcome in wave 2. Hence the model controls for the influence of unmeasured, time-invariant differences across adolescents (Cain, 1975), thereby providing less biased estimates of effects of welfare and employment patterns on changes in adolescent well-being over time (Kessler & Greenberg, 1981). In addition, the inclusion of adolescent, mother, and family demographic variables helps control for a number of characteristics associated with selection into maternal employment and welfare receipt and with adolescent well-being, thereby decreasing concerns over spurious findings. Adolescent, mother, and family control variables were drawn from wave 1 of the survey, excluding household income due to its endogeneity with welfare and employment. Additional modeling specifications added time-varying covariates from wave 2 (including changes in adolescent age, maternal marital status, maternal identity, and number of children in household) as well as income and change in income. There were no significant differences in results with these alternate specifications.

Moderation models

To assess whether maternal human capital moderates the influence of welfare and employment experiences, a series of moderation models were next estimated, sequentially adding in sets of interactions between the maternal education and literacy skills variables and the maternal welfare and employment variables. Interaction variables were entered one set at a time (e.g., education by welfare interactions) using centered continuous variables to decrease colinearity concerns and to allow results to be graphed (Aiken & West, 1991). Following procedures outlined by Aiken and West (1991), three methods were used to assess moderation: (1) whether the set of interaction terms added significant variance to the model; (2) whether significant differences were apparent between interaction groups; and (3) whether the simple slope of each interaction group was significantly different from 0 (results not shown). In short, significant interactions imply that the relationship between maternal welfare experiences or employment experiences and adolescent developmental trajectories differs as a function of mothers' human capital. To help in the interpretation of the interaction models, significant results were graphed, and posthoc bivariate analyses were conducted to add descriptive information.

A qualification to the statistical methods is that the models cannot control for unmeasured characteristics that might be correlated with welfare or employment transitions as well as with changes in adolescent outcomes, although the inclusion of a large number of important adolescent and maternal characteristics in the models helps to attenuate this concern. Alternate model specifications, such as individual fixed effects models, also can not control for unmeasured time-varying characteristics. In contrast to lagged regression models, fixed effects models do not explicitly assess the initial level of adolescent development (e.g., the wave 1 adolescent functioning variable). Perhaps most centrally, fixed effects models can not assess the effects of time-invariant predictors (e.g., can not assess the effect of stable employment on changes in adolescent outcomes). Because we were interested in assessing how both stability and change in mothers' welfare and employment experiences predicted changes in adolescent well-being and whether these relationships were moderated by mothers' human capital characteristics, lagged regression models were deemed most conceptually and statistically appropriate. Finally, it is important to note that the relatively short time period of 16 months between waves provides a limited window in which to observe change in adolescent functioning. In sum, these analyses provide a conservative test of our research questions.

Results

Sample descriptives

Table 1 presents descriptives of the sample. Forty-nine percent of the adolescents were male. Approximately 44 percent were Black, 48 percent were Hispanic, and 8 percent were White and other ethnicities. Sixty-six percent of mothers reported that English was their first language. Most of the families were poor, with an average wave 1 income that put them well below the federal poverty line (mean income-to-needs = .87; data not shown), and households had an average of 3 minors. At the first interview, adolescents averaged 12 years old, and mothers 38 years. In addition, 29 percent of the mothers were married, 40 percent did not have a high school degree, and 16 percent had education beyond high school. Mothers' literacy skills were about one half of a standard deviation below the scale norms (M = 100; SD = 15), whereas adolescents' cognitive skills were close to scale means, although they decreased very slightly by wave 2. Regarding psychosocial functioning, it is notable that more adolescents scored above the clinical cut-off on maternal reports of internalizing and externalizing behavior problems than expected (16% would be expected using scale norms).

Table 1.

Descriptives on study variables.

| Mean | Standard Deviation |

Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adolescent White/Other | .08 | .28 | 0 - 1 |

| Adolescent Black | .44 | .50 | 0 - 1 |

| Chicago | .34 | .47 | 0 - 1 |

| Boston | .37 | .48 | 0 - 1 |

| Adolescent Male | .49 | .50 | 0 - 1 |

| Adolescent Age (years) | 12.04 | 1.40 | 9 - 15 |

| Mother Age (years) | 38.18 | 8.28 | 22 - 74 |

| Mother Cohabiting | .05 | .21 | 0 - 1 |

| Mother Married | .29 | .45 | 0 - 1 |

| Mother Education < HS | .40 | .49 | 0 - 1 |

| Mother Education > HS | .16 | .36 | 0 - 1 |

| Biological Mother | .90 | .29 | 0 - 1 |

| English is 1st Language | .66 | .47 | 0 - 1 |

| Number of Minors | 3.14 | 1.52 | 1 - 8 |

| Mother Literacy Skills | 92.06 | 15.91 | 60 - 140 |

| Missing imputation | .09 | .29 | 0 - 1 |

| Adolescent Quantitative Skills W1 | 98.20 | 15.04 | 50 - 150 |

| Adolescent Quantitative Skills W2 | 95.60 | 12.63 | 50 - 150 |

| Adolescent Literacy Skills W1 | 102.32 | 19.64 | 50 - 150 |

| Adolescent Literacy Skills W2 | 100.27 | 17.91 | 50 - 150 |

| Adolescent Delinquency W1 | −.10 | .33 | −.37 - 1.08 |

| Adolescent Delinquency W2 | −.10 | .39 | −.40 – 1.76 |

| Adolescent Psychological Distress W1 | 1.51 | 1.08 | 0 - 4.29 |

| Adolescent Psychological Distress W2 | 1.54 | 1.09 | 0 - 4.09 |

| Adolescent Internalizing Problems W1 | .28 | .45 | 0 - 1 |

| Adolescent Internalizing Problems W2 | .22 | .41 | 0 - 1 |

| Adolescent Externalizing Problems W1 | .26 | .44 | 0 - 1 |

| Adolescent Externalizing Problems W2 | .29 | .46 | 0 - 1 |

Table 2 presents a descriptive portrait of mothers' welfare and employment patterns. Seventy percent of the mothers reported being stably off welfare over the two waves of the survey. This finding reiterates the difference in this representative sample of low-income urban families in comparison to other studies employing samples drawn from welfare rolls. Twelve percent of mothers received welfare at both points, and an additional 14 percent moved off welfare. Only 4 percent of mothers reported moving onto welfare. Regarding employment, 45 percent of mothers were stably not employed, and 26 percent were employed at both times. Twenty percent of mothers moved into employment and 9 percent moved out of employment.

Table 2.

Cross Tabulation of Welfare and Employment Patterns

| Stable Off Welfare 69.8% |

Onto Welfare 4.4% |

Off Welfare 13.6% |

Stable Welfare 12.2% |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stable Unemployment | 45.3% | 24.2% | 3.1% | 8.4% | 9.7% |

| Into Employment | 19.7% | 15.1% | 0.4% | 3.5% | 0.8% |

| Out of Employment | 9.3% | 7.1% | 0.4% | 0.8% | 1.0% |

| Stable Employment | 25.7% | 23.4% | 0.6% | 1.0% | 0.7% |

Note. Total percentages for exclusive welfare and employment patterns are presented in the first row and first column, respectively. Combinations of welfare and employment patterns are presented in the internal rows and columns.

Table 2 also presents cross tabulations between the welfare and employment patterns, indicating the relative lack of dependence between the two income sources in this sample of low-income mothers. The first notable results from this cross tabulation are that within the group of mothers off welfare both waves, equal proportions were stably not employed (24 percent) and stably employed (23 percent). Sizable groups also were not on welfare at either of the two time points, but were moving into (15 percent) or out of (7 percent) employment. A second notable pattern is that within the subsample of mothers moving off welfare, only about one quarter were moving into employment. Similarly, within the group of mothers moving into employment, less than one fifth were moving off welfare over the same time period. Finally, sizable groups were not employed at either time point, but were remaining on welfare (10 percent), or moving off welfare (8 percent). These results suggest that welfare and employment are operating relatively independently in this sample. Thus, combining welfare and employment status into one coherent set of mutually exclusive categories (e.g., from welfare to employment, from not welfare to employment, etc) is not feasible. Additional regression analyses predicting adolescent developmental trajectories tested interactive models (not shown), and also supported the conclusion to model welfare and employment experiences independently.

Main Effects of Welfare and Employment Experiences

Table 3 presents the main effects ordinary least squares (OLS) regression models for the six adolescent outcomes. Regarding the central welfare and employment transition variables of interest, asterisks signify significant differences in comparison to the omitted group (never welfare and never employment respectively), while postscripts signify significant differences between the groups included in the model (e.g., onto welfare versus off welfare in the model predicting adolescent delinquency). The main effects models revealed a notable lack of significant links between mothers' welfare and work experiences and changes in adolescent functioning over a 16 month period. The only results that reached statistical significance at conventional levels found that entrances onto welfare predicted relative increases in delinquency in comparison to stability off welfare or movements off welfare.

Table 3.

Main effect lagged OLS regression models for welfare and employment experiences on adolescent functioning.

| Quantitative Skills | Literacy Skills |

Delinquency | Psych. Distress |

Internal. Problems |

External. Problems |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adol. Outcome Wave 1 | .55** | .70** | .47** | .39** | .42** | .52** |

| Welfare Experience | ||||||

| Onto Welfare | .00 | −.03 | .11* a | .02 | .08+ | .11+ |

| Off Welfare | −.01 | .01 | −.01a | .04 | .04 | .05 |

| Stable Welfare | −.08+ | −.03 | .08 | .03 | .07 | .05 |

| Employment Experience | ||||||

| Into Employment | −.01 | −.04 | −.06 | −.10+ | −.07 | .01 |

| Out of Employment | −.01 | .02 | −.06 | .02 | .04 | .01 |

| Stable Employment | .03 | −.04 | −.04 | −.11+ | −.02 | −.07 |

| Control Variables | ||||||

| Adol. White/Other | −.01 | −.01 | .05 | .09 | .05 | .13* |

| Adol. Black | −.17** | −.13* | −.06 | −.03 | −.10 | −.01 |

| Chicago | .02 | .13* | .05 | −.00 | .08 | .06 |

| Boston | .01 | .08+ | −.01 | −.09 | .09 | .02 |

| Adol. Male | −.02 | −.12** | .06 | −.12* | .10* | −.04 |

| Adol. Age (months) | −.09* | .00 | .08+ | .11* | −.05 | .02 |

| Mother Age (years) | .04 | .03 | −.05 | −.03 | −.10+ | −.10+ |

| Mother Cohabiting | .06+ | −.00 | .03 | .02 | .04 | −.01 |

| Mother Married | .07 | −.01 | −.08+ | .00 | −.06 | −.12** |

| Mother Educ < HS | −.03 | −.05 | −.04 | −.04 | −.05 | .03 |

| Mother Educ > HS | .03 | .00 | .08 | .04 | .01 | −.02 |

| Biological Mother | .02 | .06 | −.08 | −.04 | −.05 | −.08 |

| English is 1st Language | .02 | −.03 | .05 | −.02 | .06 | −.01 |

| # of Minors | −.00 | .03 | −.05 | −.01 | −.04 | .05 |

| Mother Literacy Skills | .07 | .13** | −.00 | .07 | −.06 | .05 |

| Missing imputation | .02 | −.02 | −.06 | −.02 | .01 | −.05 |

| F of Model | 10.07** | 28.82** | 6.32** | 6.20** | 7.69** | 15.10** |

| R2 | .44 | .63 | .33 | .25 | .27 | .36 |

| Model N | 807 | 794 | 816 | 804 | 823 | 823 |

Notes. Betas or standardized coefficients are reported.

p < .01

p < .05

p < .10

Moderation Results

Table 4 presents results from the maternal literacy skills interaction models, and Table 5 presents results from the maternal education interaction models assessing whether mothers' human capital characteristics moderate the relationships between maternal welfare and work experiences and adolescent developmental trajectories. Tables 4 and 5 show only the coefficients for the interaction terms and do not repeat all of the main effects coefficients for each interaction model.

Table 4.

Interactions between maternal welfare and employment patterns and maternal literacy skills.

| Quantitative Skills | Literacy Skills |

Delinquency | Psych. Distress |

Internal. Problems |

External. Problems |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel 1. Welfare X Maternal Literacy Skills Interactions | ||||||

| Onto Welfare X M Skills | −.00 | .00 | −.03 | −.03 | .01 | .04 |

| Off Welfare X M Skills | .04 | −.03 | −.01a | −.08+ | .03 | −.04 |

| Stable Welfare X M Skills | .10 | −.03 | −.11**a | −.13** | −.02 | −.00 |

| F of Interaction Terms | .89 | .58 | 2.78* | 5.79** | .31 | .46 |

| R2 | .45 | .64 | .34 | .26 | .27 | .36 |

| Model N | 807 | 794 | 816 | 804 | 823 | 823 |

| Panel 2. Employment X Maternal Literacy Skills Interactions | ||||||

| Into Employ X M Skills | .03a | −.01 | −.05 | −.01a | .04 | .02 |

| Out of Employ X M Skills | −.07*a b | −.03 | .00 | .14*a | −.04 | −.05 |

| Stable Employ X M Skills | .04b | −.02 | .00 | .10* | .03 | .00 |

| F of Interaction Terms | 2.37+ | .20 | .50 | 3.31* | .54 | .74 |

| R2 | .45 | .64 | .33 | .27 | .27 | .36 |

| Model N | 807 | 794 | 816 | 804 | 823 | 823 |

Notes. Standardized beta coefficients are reported. Shared superscripts within a panel and column indicate a difference at p < .05. All interaction models include all main effects variables as shown in Table 3.

p < .01

p < .05

p < .10

Table 5.

Interactions between maternal welfare and employment patterns and maternal education.

| Quantitative Skills | Literacy Skills |

Delinquency | Psych. Distress |

Internal. Problems |

External. Problems |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel 1. Welfare X Maternal Education Interactions | ||||||

| Onto Welfare X < HS | .03 | .04 | −.08a | −.07a | −.11+ | .06 |

| Off Welfare X < HS | .03 | .07 | −.05 | .00 | −.10 | −.03 |

| Stable Welfare X < HS | −.05 | .03 | −.01 | .12a | −.05 | −.02 |

| Onto Welfare X > HS | −.01 | .07** | .04a | −.03 | −.06 | −.02 |

| Off Welfare X > HS | .01 | .08 | .08 | .04 | .09 | −.02 |

| Stable Welfare X > HS | −.04 | .03 | .03 | .02 | .00 | .04 |

| F of Interaction Terms | .30 | 1.70 | 1.14 | 1.17 | 1.27 | .38 |

| R2 | .44 | .64 | .34 | .26 | .29 | .37 |

| Model N | 807 | 794 | 816 | 804 | 823 | 823 |

| Panel 2. Employment X Maternal Education Interactions | ||||||

| Into Employ X < HS | .00 | −.03 | .01 | −.04 | −.02a | .01 |

| Out of Employ X < HS | −.09a | −.02 | .06 | −.01 | .04 | .15*a |

| Stable Employ X < HS | .09a | .05 | .07 | −.00 | .04 | .01a |

| Into Employ X > HS | .10+ | .01 | .01 | .05 | −.16*a b | .03b |

| Out of Employ X > HS | −.03b | −.03 | −.01 | −.07 | .07b | .16**b c |

| Stable Employ X > HS | .14* b | .02 | −.10 | .13+ | −.08 | −.01c |

| F of Interaction Terms | 1.85+ | .45 | 1.02 | .97 | 1.41 | 3.08** |

| R2 | .46 | .64 | .34 | .26 | .29 | .38 |

| Model N | 807 | 794 | 816 | 804 | 823 | 823 |

Notes. Standardized beta coefficients are reported. Shared superscripts within a panel and column indicate a difference at p < .05. All interaction models include all main effects variables as shown in Table 3. For delinquency, stable employment versus out of employment for mothers with less than a high school degree in comparison to more than a high school degree is also significant.

p < .01

p < .05

p < .10

Maternal literacy skills interactions

The first panel of Table 4 presents interaction coefficients between maternal welfare experiences and maternal literacy skills, with significant results found for adolescent delinquency and psychological distress. Globally, maternal literacy skills appear most positively linked with adolescent development among teens of mothers who remain on welfare. Regarding adolescents' engagement in delinquency, results indicate that maternal literacy skills are protective, promoting relative decreases in delinquency, for adolescents of mothers who remained on welfare in comparison to those whose mothers were stably off welfare (the omitted group) or exited welfare (as indicated by postscripts). In contrast, the combination of stable welfare receipt and low maternal literacy skills predicted increased adolescent delinquency. A similar pattern is seen for psychological distress, in which literacy skills promoted relative declines in psychological distress for adolescents of mothers stably on welfare in comparison to those stably off welfare. This result is graphed in Figure 1. The negative slope of the stable welfare group indicates the link between greater maternal literacy skills and relative declines in adolescent psychological distress. The combination of low literacy skills and stable welfare receipt led to the greatest growth in adolescent psychological distress.

Figure 1.

Welfare experiences X maternal literacy skills predicting adolescent psychological distress.

Mothers' literacy skills also moderated the relationship between maternal employment experiences and adolescent functioning (Panel 2), with results clustered in the models predicting quantitative skills and psychological distress. These results indicate that loss of employment by mothers with greater literacy skills predicted declines in adolescent functioning, whereas employment loss in mothers with low literacy skills predicted improvements in adolescent functioning. Specifically, greater maternal literacy skills were associated with relative declines in adolescent quantitative skills following mothers' loss of employment, in contrast to adolescents whose mothers retained, moved into, or remained stably out of employment. Figure 2 presents these results graphically. The significant negative slope of the out of employment group shows the substantial cost of losing employment for youth of highly skilled mothers. In addition, the stable employment group showed relative improvements in adolescents' quantitative skills when mothers have higher literacy skills (the slope for this group is significant at p < .05). Results for psychological distress show a similar interaction between maternal literacy skills and employment. Adolescents showed relative declines in functioning (increases in psychological distress) when mothers with higher literacy skills moved out of employment, as opposed to being stably not employed or moving into employment. Here, however, greater maternal literacy also interacted with stable employment to predict relative increases in psychological distress.

Figure 2.

Employment experiences X maternal literacy skills predicting adolescent quantitative skills.

Maternal education interactions

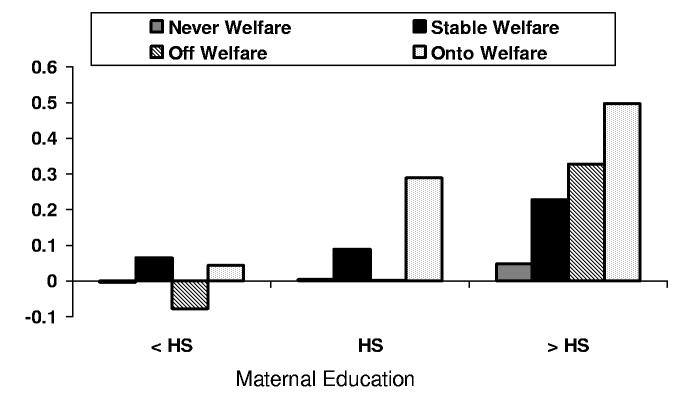

For the interactions with maternal education, shown in Table 5, the two dummy variables of less than high school and more than high school education were interacted with the three welfare variables, leading to a set of six interaction terms (the same was then done with the three employment variables). In the set of interactions with maternal welfare experiences, significant moderation effects were found for adolescents' literacy skills, delinquency, and psychological distress, with a similar pattern for internalizing problems, although little added variance was accounted for in the models. The predominant pattern occured in the measures of adolescent psychosocial functioning, showing that moving onto welfare was protective for adolescents of mothers with low education. Adolescents of mothers with less than a high school degree who moved onto welfare showed relative declines in delinquency compared to teens of mothers with higher education moving onto welfare, who showed relative increases. Likewise, adolescents of mothers with less than a high school degree who moved onto welfare showed relative declines in psychological distress in comparison to their peers in low education families who remained on welfare. A similar result is seen for internalizing problems, with a larger, albeit only marginally significant, coefficient, such that adolescents of mothers with low education who moved onto welfare showed relative declines in serious internalizing behaviors in comparison to their peers of mothers who remained stably off welfare. This pattern of results is exemplified in Figure 3, which presents the welfare by education interaction predicting changes in delinquency. This figure indicates that moving onto welfare is relatively beneficial for adolescents of less educated mothers in comparison to the detrimental effect for adolescents of more highly educated mothers. For cognitive skills, a different pattern emerged. Here results indicate that mothers with education beyond high school who entered welfare had adolescents that showed a relative increase in literacy skills, in comparison to their peers in nonwelfare families. It is important to note that the former group is very small, and hence caution is urged in interpreting this finding.

Figure 3.

Welfare experiences X maternal education predicting adolescent delinquency.

The second panel of Table 5 presents interactions between maternal education and employment experiences, showing a myriad of significant patterns. In short, these results suggest that losing employment is most detrimental, and gaining or sustaining employment most beneficial, for adolescents of more educated mothers. For quantitative skills, a number of significant differences emerged. Results suggest that stable employment and movements into employment (the later at trend level) led to greater relative gains in adolescent cognitive skills than a loss of employment or stable lack of employment when mothers had education beyond high school in comparison to a high school degree. Stable employment was also more beneficial than loss of employment for less educated mothers.

Results for maternal reports of adolescents' behavioral and psychological problems show a similar pattern, with movements into employment most beneficial, and loss of employment most detrimental, for adolescents of more highly educated mothers. Specifically, for internalizing problems, mothers' movements into employment were more beneficial for adolescents of mothers with greater than a high school degree than for those with less than or equal to a high school degree. Similarly, loss of employment predicted increased internalizing for adolescents of the most educated mothers. Figure 4 shows these results in graphical form, highlighting the increases in internalizing problems following employment loss as maternal education rises, and the decreases in adolescent internalizing following mothers' movements into employment for adolescents of the most highly educated mothers.

Figure 4.

Employment experiences X maternal education predicting adolescent serious internalizing problems.

Results for externalizing problems show overlapping patterns. Loss of employment led to increases in serious externalizing within adolescents of the most highly educated mothers. Loss of employment also led to relative increases in serious externalizing behavior for adolescents of less educated mothers.

Alternate model specifications

A number of alternate model specifications were assessed, to test the robustness of the findings. As noted earlier, models were run controlling for time-varying covariates and then for household income and changes in income. All patterns of results reported above remained unchanged. In addition, different definitions of employment were assessed, defining employment as full time (40 hours per week or more), or any employment (1 hour per week or more). Again, the pattern of results remained quite consistent (results not shown).

Summary of Results

In summary, the analyses found very limited main effects of mothers' welfare and work patterns on adolescent functioning, with only one significant result showing movements onto welfare predicting relative increases in adolescent delinquency. Results for interactions between welfare and employment experiences and mothers' human capital characteristics unearthed four primary patterns that appeared across multiple measures of adolescent functioning. First, consistent and increased employment was most beneficial for the cognitive and psychosocial functioning of adolescents of more educated mothers. Conversely, employment loss was most detrimental for adolescent functioning in families with greater human capital resources, including maternal education beyond high school and high literacy skills. To aid explanation of these results, post hoc bivariate analyses were conducted, which indicated that mothers with more education commanded higher wage rates and were more likely to have access to health insurance through their employers than their less educated counterparts, two central indices of employment quality. Mothers with better literacy skills also commanded higher wages. These patterns suggest that mothers with greater human capital received elevated economic and in-kind payback from employment.

A third pattern of results that emerged showed that movements onto welfare were detrimental for adolescent functioning when they occurred among highly educated mothers but were associated with improved functioning among teens of the least educated mothers. Although measures of welfare stigma were not available in the data set, less educated mothers reported lower self esteem and greater psychological distress than their more educated counterparts, and hence perhaps their families benefited more from the safety net of welfare. The fourth pattern indicated that greater maternal literacy skills appeared protective in the face of continued welfare receipt by mothers.

Across these findings, it is important to acknowledge that the effect sizes were consistently small, and that moderation effects of mothers' education and literacy skills were apparent within less than half of the models tested. As noted, however, these patterns appeared across numerous outcomes, with the most robust findings apparent in the realm of adolescents' psychosocial functioning, particularly using adolescent self reports.

Discussion

Previous research has found mothers' welfare and work experiences following PRWORA to be minimally and inconsistently linked with adolescents' developmental well-being in poor families (e.g., Chase-Lansdale et al., 2003; Gennetian et al., 2004). This research sought to provide a more nuanced perspective to assessing longitudinal relations between low-income mothers' welfare and employment experiences and young adolescents' cognitive, behavioral, and psychological trajectories during the post welfare reform era. Drawing on theoretical models which posit interactive influences between multiple characteristics of individuals' environments (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998; Lerner, 1998) and the central role of parents' human capital characteristics for child development and family environments (Becker, 1991), analyses assessed whether maternal human capital characteristics moderated the influence of maternal welfare and employment experiences on adolescent development. In short, results supported this contention, finding that mothers' patterns of welfare and employment predicted changes in adolescent functioning differentially, depending on the level of skill and education mothers had attained.

Patterns of Welfare and Work

This work builds upon a small array of diverse and conflicting findings concerning low-income women's transitions off welfare and into employment and consequences for children's well-being. In contrast to other welfare reform research, we employed a representative sample of low-income families from low-income urban communities and considered women's welfare and employment experiences concurrently but independently. In short, this view argues that welfare and work are not opposites or substitutes for one another: low-income women leave the welfare rolls but do not necessarily enter into stable employment. Similarly, some women lose their job but access alternative financial supports rather than enter welfare. Indeed, descriptive results from this sample indicate that of the women moving into employment over the time period of the study, less than one fifth were moving out of welfare, and of the women who lost employment, less than one tenth entered welfare. Moreover, during the approximately two years assessed in this study, nearly one quarter of the mothers were neither on welfare nor employed consistently, and nearly another quarter were consistently employed and not accessing welfare. In short, our results indicate the importance both of assessing women's welfare and work experiences independently, and of considering movements both into and out of these states rather than seeing welfare reform as enabling only a one-way street from welfare dependence into the labor force. As such, this work provides a broader view of the welfare and employment experiences of low-income women and families than research focusing solely on a population of welfare recipients or solely on exits from welfare and entrances into employment. Other research supports this contention, noting the complex psychological, family, economic, and policy factors that influence low-income mothers' employment and welfare decisions (Harris, 1996). In the following sections, we review the primary patterns of findings, arguing that overall these results support conceptual models of synergistic or cumulative effects (Evans, 2004; Rutter, 1993) and risk buffering (Yoshikawa, 1999).

Greater Human Capital Enhances Benefits of Employment and Exacerbates Risks of Employment Loss

One of the primary patterns of findings unearthed in these results indicated that higher maternal educational attainment enhanced positive links between moving into employment or sustained employment and improvements in early adolescent functioning in both cognitive and psychosocial realms. These results suggest a synergistic or cumulative effect whereby families with the greatest maternal education resources had the most to gain from stable employment. In short, these results support a story of relative rewards - with the push of welfare reform and a strong economy, mothers with greater education may be more likely to find more stable, higher paying, more stimulating jobs, which in turn may create a better model for their adolescents and also improve their own well-being. Indeed, women with higher education in this sample commanded higher wage rates and also were more likely to have access to health insurance through their employer, two central indicators of employment quality. Moreover, a high school degree or higher education was also linked with more positive self concept and lower psychological distress among mothers. As other research suggests (Menaghan and Parcel, 1994; 1995; Morris & Coley, 2004; Raver, 2003), if lower education leads to lower quality and less stimulating jobs, this may increase women's stress and decrease both their functioning and the quality of the home environment and parenting that they provide their children, thereby harming children's development.

The inverse of relative rewards is relative losses; interaction results also suggest that more highly skilled mothers and their families may have the most to lose from a loss of employment. When mothers with greater than a high school education or with higher literacy skills lost employment over the two waves of the study, adolescents in turn showed relative declines in cognitive skills and psychosocial functioning. If mothers with greater human capital access more financially rewarding or stimulating jobs, then the loss of such jobs may have the most significant impact. These findings follow a set of developmental results indicating that loss of parental employment and income predicts decrements in family processes and parenting, hence harming adolescent functioning (e.g., Conger et al., 2002; McLoyd et al., 1994). Such results suggest the need for continued attention to the risks of employment loss, a topic that has been somewhat neglected in the push to follow women leaving welfare and entering jobs. Although the years proceeding welfare reform saw a substantial economic expansion and increased job creation, in the early years of the 21st century the economy lagged and unemployment rates rose substantially. Newer data are required to assess the effects of this restricted economic environment on low-income workers and their children.

In contrast to this quite consistent pattern of results for the most highly skilled and educated women in our sample, there was less consistency among mothers with the lowest human capital. On one hand, a loss of employment was least detrimental for adolescents of women with lower maternal literacy skills. But with education, there was indication of a curvilinear pattern, with employment loss being more detrimental for adolescents of mothers with less than or greater than a high school degree versus those with mid levels of education. In the increasingly competitive global market, our understanding is limited regarding the employment opportunities and experiences of adults who have not attained basic secondary education credentials. In addition, mothers' education and literacy skills may be tapping into somewhat distinct aspects of human capital. Educational attainment is an important indicator of access to wealth and power and is also linked to supportive family processes. Literacy skills, on the other hand, may have stronger links with day-to-day family functioning (Hair, McGroder, Zaslow, Ahluwalia, & Moore, 2002). More attention is needed to assess how various aspects of human capital affect family and child functioning in both overlapping and distinct manners.

Education Moderates Movements Onto Welfare

A second pattern that emerged in the results found that maternal education moderated the link between movements onto welfare and adolescent trajectories. Movements onto welfare were associated with improvements in adolescents' behavioral and psychological functioning if mothers had limited education, but with declines in adolescent well-being in families with more maternal education. Given that time period of data collection, 3 to 5 years after the implementation of PRWORA, relatively few women in the sample entered welfare, and this was particularly unusual among more highly educated women. Nonetheless, results suggest that welfare may offer an important source of support for women with limited educational and psychological resources, providing a buffer and source of stable income in times of need. In contrast, for women with higher education, movements onto welfare predicted increases in adolescents' delinquency and psychological distress. Although little research has assessed adolescents' understanding and views of welfare (but see Coley, Kuta, & Chase-Lansdale, 2000), it is possible that teens of more educationally successful mothers react with greater embarrassment or distress at the necessity of accessing welfare. Alternately, as noted by Gennetian & Miller (2002), new welfare recipients with greater human capital resources may be experiencing numerous stressful life changes such as marital transitions or loss of other income streams that exacerbate their experiences with demanding welfare requirements.

Greater Literacy Skills Buffer Continued Welfare Receipt

A final pattern of results unearthed in these analyses suggest that maternal literacy skills moderate the link between welfare experiences and adolescent psychosocial functioning. In particular, continued welfare receipt was buffered by greater maternal literacy skills, predicting improved psychosocial functioning for adolescents of more highly skilled mothers, but relative declines in functioning when combined with low maternal literacy skills. These results agree with Yoshikawa (1999), who found that a combination of low maternal education and longer welfare receipt was linked with particularly poor child functioning among a sample of younger children. In this sample, mothers with low literacy skills also reported low levels of self esteem. Such negative feelings about one's self may be exacerbated by the stigma of continued welfare receipt in this age of increasingly diligent efforts to move women off the welfare rolls. Mothers with low literacy skills and education are also likely to have particularly limited employment prospects, and indeed we found that they commanded the lowest wage rates. Thus, such mothers may remain on welfare due to a lack of other financial options (rather than because of a transitional need, for example). These families may be most at risk over the long term, as time limits hit and families permanently lose the option of welfare as a safety net. New support systems may need to be devised to help increase mothers' skill sets and provide new mechanisms of support for families with limited employment skills and economic opportunities.

Conclusions

Results from these analyses indicated that mothers' experiences in the labor market and welfare system had sparse main effects on adolescents' short-term developmental trajectories, but that these relationships were moderated by mothers' human capital characteristics. Overall, these findings suggest a story of relative rewards and relative losses. Adolescents of mothers with greater education and skills may have the most to gain from their mothers' entrance and stability in the labor market, but these same groups also may suffer most significantly when mothers lose employment or enter the welfare rolls. It is important to note, however, that effect sizes were small and the results not robust across all measures of adolescent well-being, although they were concentrated most heavily among measures of teens' psychosocial functioning. Adolescents' emotional and behavioral well-being may be more reactive to perturbations in family experiences, showing relatively quick reactions to major transitions such as job loss. Cognitive skills and learning trajectories, on the other hand, may take longer to react to external forces (Chase-Lansdale et al., 2003). In addition, adolescents' cognitive skills show greater continuity than socio-emotional functioning, perhaps due to longer-term effects of early child experiences, influence of genetic differences, and consistency of poor educational systems serving many urban poor neighborhoods (National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, 2000).

One overarching interpretation is that this interactive view of influences on low-income adolescents still represents too simple a model. As noted by developmental theorists (e.g., Evans, 2004; Rutter, 1993), the impact of stressors often function conjointly and multiplicatively, producing an amplification of effects. Indeed, research has noted the multiple environmental and social stressors faced by children raised in poverty, such as poor educational and housing conditions, health problems, pollution, and low cognitive stimulation and warmth from parents, to name just a few (Evans, 2004). The most disadvantaged families (e.g., with low human and financial capital) within such demanding environments may already suffer from multiple stressors, such that a single change in an arena such as welfare receipt or maternal employment presents an inadequate trigger to influence developmental change.

In considering these results, it is essential to keep in mind that the data were collected under very favorable economic and social conditions, during years of a steady and significant economic expansion when jobs were plentiful and incomes were rising for all but the most severely disadvantaged. In the economic decline that has occurred since these data were collected, employment opportunities for workers at the lowest rungs have become more constricted, welfare time limits have begun to hit, and incomes may have stagnated or declined for some families. Hence, the welfare and employment experiences of low-income families may have shifted, influencing the well-being of their children as well. As welfare reform evolves, trends in family functioning and adolescent well-being may continue to diverge. Adolescents of mothers who become firmly entrenched in the job market and improve their families' financial status and stability may show continued improvements in multiple arenas of well-being. For adolescents in more unstable families, such as those in which mothers move in and out of the work force, or who suffer serious financial instability related to a loss of public benefits, even more significant decrements in functioning may occur. In sum, results from this study add both new knowledge and new puzzles to the growing base of research on welfare and employment transitions and adolescent well-being among low-income families, suggesting that the proposal of a single, uniform story to explain the effects of welfare reform and maternal employment changes may be too simple a goal.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The Three City Study was funded by: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (RO1 HD36093), Office of the Assistant Secretary of Planning and Evaluation, Administration on Developmental Disabilities, Administration for Children and Families, Social Security Administration, and National Institute of Mental Health; The Boston Foundation, The Annie E. Casey Foundation, The Edna McConnell Clark Foundation, The Lloyd A. Fry Foundation, The Hogg Foundation for Mental Health, The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, The Joyce Foundation, The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, The W.K. Kellogg Foundation, The Kronkosky Charitable Foundation, The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, The Charles Stewart Mott Foundation, The David and Lucile Packard Foundation, The Searle Fund for Policy Research, and The Woods Fund of Chicago. A special thank you is extended to the families who participated in the Three-City Study. A previous version of this paper was presented at the March, 2004 meetings of the Society for Research in Adolescence, Baltimore, MD.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/2-3 and 1992 Profile. University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; Burlington, VT: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage Publications; Newbury Park: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Becker G. A Treatise on the Family: Enlarged Edition. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett N, Lu H, Song Y. Welfare reform and changes in the economic well-being of children. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2002. Working Paper. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi S. Maternal employment and time with children: Dramatic change or surprising continuity? Demography. 2000;37:401–414. doi: 10.1353/dem.2000.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blank R, Haskins R. The new world of welfare. Brookings Institution Press; Washington, D.C.: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Borus ME, Carpenter SW, Crowley JE, Daymont T,N, et al. A final report on the National Survey of Youth labor market experience in 1980. II. Center for Human Resource Research, The Ohio State University; Columbus, Ohio: 1982. Pathways to the future. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U, Morris PA. The ecology of developmental processes. In: Damon W, Lerner RM, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Theoretical models of human development. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1998. pp. 993–1028. [Google Scholar]

- Cain GG. Regression and selection models to improve nonexperimental comparisons. In: Bernett CA, Lumsdiane AA, editors. Evaluation and experiment. Academic Press; New York, NY: 1975. pp. 297–317. [Google Scholar]

- Cancian M, Meyer DR. Alternate measures of economic success among TANF participants: Avoiding poverty, hardship, and dependence on public assistance. Journal of Policy Analysis and Measurement. 2004;23:531–548. [Google Scholar]

- Chase-Lansdale PL, Moffitt R, Lohman BJ, Cherlin A, Coley RL, Pittman LD, Roff J, Votruba-Drzal E. Mothers' transitions from welfare to work and the well-being of preschoolers and adolescents. Science. 2003;299:1548–1552. doi: 10.1126/science.1076921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coley RL, Chase-Lansdale PL. Welfare receipt, financial strain, and African-American adolescent functioning. Social Service Review. 2000;74:380–404. [Google Scholar]

- Coley RL, Kuta AM, Chase-Lansdale PL. An insider view: Knowledge and opinions of welfare from African American girls in poverty. Journal of Social Issues. 2000;56:709–727. [Google Scholar]

- Conger K, Rueter M, Conger R. The role of economic pressure in the lives of parents and their adolescents: The family stress model. In: Crockett LJ, Silbereisen RJ, editors. Negotiating adolescence in times of social change. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, England: 2002. pp. 201–223. [Google Scholar]

- Danziger SK, Kalil A, Anderson NJ. Human capital, physical health, and mental health of welfare recipients: Co-occurrence and correlates. Journal of Social Issues. 2000;56:635–655. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR. BSI 18: The Brief Symptom Inventory 18: Administration, Scoring and Procedures Manual. National Computer Systems, Inc; Minneapolis: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, Chase-Lansdale PL. Welfare reform and children's well-being. In: Blank R, Haskins R, editors. The new world of welfare. The Brookings Institute; Washington, D.C.: 2001. pp. 391–417. [Google Scholar]

- Dunifon R, Kalil A. Maternal welfare and work combinations and adolescents' school progress. Cornell University: Department of Policy Analysis and Management; 2003. Working Paper. [Google Scholar]

- Elder G. Children of the Great Depression. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW. The environment of childhood poverty. American Psychologist. 2004;59(2):77–92. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.2.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman SS, Elliott GR. At the threshold: The developing adolescent. Harvard University Press; Cambridge: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Gennetian L, Duncan G, Knox V, Vargas W, Clark-Kauffman B, London AS. How welfare policies for affect adolescents' school outcomes: A synthesis of evidence from experimental studies. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2004;14:399–423. [Google Scholar]

- Gennetian LA, Miller C. Children and welfare reform: A view from an experimental welfare program in Minnesota. Child Development. 2002;73:601–620. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold M. Delinquent behavior in an American city. Brooks/Cole; Belmont, CA: 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Hair EC, McGroder SM, Zaslow MJ, Ahluwalia SK, Moore KA. How do maternal risk factors affect children in low-income families? Further evidence of twogenerational implications. Journal of Prevention and Intervention in the Community. 2002;23:65–94. [Google Scholar]

- Harris KM. Life after welfare: Women, work, and repeat dependency. American Sociological Review. 1996;61:407–426. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman L, Youngblade L. Mothers at work: Effects on children's well-being. Cambridge University Press; New York, NY: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R, Greenberg EF. Linear panel analysis: Models of quantitative change. Academic Press; New York: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Knitzer J, Yoshikawa H, Cauthen NK, Aber J. Welfare reform, family support,and child development: Perspectives from policy analysis and developmental psychopathology. Development & Psychopathology. 2000;12:619–632. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400004041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner RM. Theories of human development: Contemporary perspectives. In: Lerner RM, editor. Handbook of child psychology 5th Edition Volume 1: Theoretical models of human development. Wiley; New York: 1998. pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Lohman BJ, Pittman LD, Coley RL, Chase-Lansdale PL. Welfare history, sanctions, and developmental outcomes among low-income children and youth. Social Service Review. 2004;78:41–73. [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC. Socioeconomic disadvantage and child development. American Psychologist. 1998;53:185–204. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd V, Jayaratne T, Ceballo R, Borquez J. Unemployment and work interruption among African American single mothers: Effects on parenting and adolescent socioemotional functioning. Child Development. 1994;65:562–589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menaghan E, Parcel T. Early parental work, family social capital, and early childhood outcomes. American Journal of Sociology. 1994;99:972–1009. [Google Scholar]

- Menaghan E, Parcel T. Social sources of change in children's home environments: The effects of parental occupational experiences and family conditions. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1995;57:69–84. [Google Scholar]