Summary

Riboswitches are RNA-based genetic control elements that regulate gene expression in a ligand-dependent fashion without the need for proteins. The ability to create synthetic riboswitches that control gene expression in response to any desired small-molecule ligand will enable the development of sensitive genetic screens that can detect the presence of small molecules, as well as designer genetic control elements to conditionally modulate cellular behavior. Herein we present an automated high throughput screening method that identifies synthetic riboswitches that display extremely low background levels of gene expression in the absence of the desired ligand and robust increases in expression in its presence. Mechanistic studies reveal how these riboswitches function and suggest design principles for creating new synthetic riboswitches. We anticipate that the screening method and design principles will be generally useful for creating functional synthetic riboswitches.

Introduction

Riboswitches are RNA-encoded genetic control elements that regulate gene expression in a ligand-dependent fashion without the need for proteins.[1–3] Riboswitches are comprised of an aptamer domain, which recognizes the ligand, and an expression platform, which couples ligand binding to changes in gene expression.[1, 4] Riboswitches are widespread in prokaryotes,[5–8] and more recent studies have revealed that riboswitches also control gene expression in eukaryotes. [9, 10] In addition to natural riboswitches that control gene expression in response to endogenous metabolites, a variety of synthetic riboswitches that respond to non-endogenous small molecules have been developed.[11–16] In principle, synthetic riboswitches can be engineered to respond to any non-toxic, cell-permeable molecule that is capable of interacting with an RNA. As such, synthetic riboswitches represent versatile ligand-dependent gene expression systems with great potential to detect the production of small molecules for applications in directed evolution or metabolic engineering. While methods to select aptamers that bind to small molecule targets are well-established,[17] general methods of converting these aptamers into riboswitches that function optimally in prokaryotic cells are not. To fully exploit their potential, it is critical to develop new methods to create synthetic riboswitches that function in bacteria.

A variety of methods have been used to create synthetic riboswitches that control eukaryotic transcription or translation. Werstuck and Green created synthetic riboswitches that regulate translation by cloning aptamer sequences into the 5′-untranslated regions (5′-UTR) of eukaryotic mRNA sequences. Binding of the ligand increased the strength of the RNA secondary structure in the 5′-UTR and reduced the translation of downstream coding regions.[16] This approach was adopted by the groups of Wilson,[12] Pelletier,[13] and Suess [15] to create synthetic riboswitches that repress eukaryotic protein translation in response to small-molecule ligands. Buskirk et al.[18] created an aptamer-based transcriptional control system that promotes ligand-dependent transcription yeast, and Gaur and co-workers used an aptamer to control ligand-dependent RNA splicing.[19] In addition to systems where regulation occurs in cis, a variety of riboregulators have been used to affect eukaryotic translation in trans.[20–23]

Given that most natural riboswitches have been identified in prokaryotes, it is perhaps surprising that there are relatively few examples of synthetic riboswitches that function in bacteria. Seuss et al.[14] created a riboswitch based on a designed helix-slipping mechanism that activates protein translation in a theophylline-dependent manner in the Gram-positive bacterium B. subtilis, and we reported a theophylline-sensitive riboswitch that activates protein translation in the Gram-negative bacterium E. coli.[11] While our previously reported synthetic riboswitches were useful in several contexts, three important issues remained unresolved. First, these switches did not completely repress protein translation in the absence of the ligand. Second, the most effective switch showed a signal to background ratio (activation ratio) of approximately 8 in the presence of 500μM theophylline. While this 8-fold increase allowed us to perform both genetic screens and selections to detect the presence of theophylline, for more demanding screening applications, an increase in the ratio of signal to background is desirable. Finally, while we determined that these riboswitches operated post-transcriptionally, we were unable to determine their precise mechanisms of action. To address these issues, we developed a high-throughput screen that enables the identification of synthetic riboswitches that display very low background levels of translation in the absence of ligand and dramatically higher signal-to-background ratios. Sequence analysis allowed us to propose and test a model for synthetic riboswitch function, and to also explain the mechanism of action of our previously reported synthetic riboswitches. Our results show that starting from a single aptamer, there are many different ways to create functional riboswitches, consistent with the notion that natural riboswitches may be derived from small molecule-binding RNA aptamers that were subsequently recruited to regulate gene expression. We anticipate that the high throughput assay described herein will be generally useful for discovering synthetic riboswitches with new ligand specificities and better performance characteristics.

Results and Discussion

We previously observed that changing the length of the sequence separating the theophylline aptamer and the ribosome binding site (RBS) had dramatic effects on both the function and dynamic range of a synthetic riboswitch.[11] However, we could not determine precisely how these changes exerted their effects. We anticipated that by randomizing the RNA sequence in this region and screening the library for function, we could identify improved switches and possibly gain insight into their mechanisms of action. Because the sequence space of RNA is relatively small, most, if not all, potential sequences can be sampled in the context of a simple genetic screening experiment.

Creation of a Library of Randomized Mutants

We previously created synthetic riboswitches by cloning a theophylline-binding aptamer [24–27] at various locations upstream of the ribosome binding site of a β-galactosidase reporter gene (IS10-lacZ) that was controlled at the transcriptional level by a weak, constitutively active IS10 promoter (Figure 1A). To increase the overall signal, we replaced the IS10 promoter with the stronger Ptac1 promoter.[28] As expected, the tac promoter enhances the level of β-galactosidase expression in the presence of theophylline, but also increases the background expression ~80-fold from ~10 Miller units[11] to ~800 Miller units (Figure 1B).

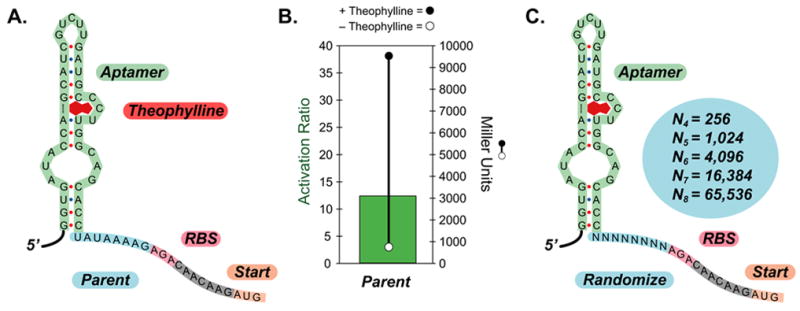

Figure 1. Diagram of the 5′-region of a synthetic riboswitch, the performance of the synthetic riboswitch, and the randomization strategy.

A.) Sequence of a portion of the 5′-region of the parent synthetic riboswitch with 8-bases separating the aptamer (green) and the ribosome binding site (pink); the AUG start codon (peach) is highlighted. The aptamer is shown in the secondary structure predicted for the theophylline aptamer by mFold and confirmed experimentally.

B.) Measures of the activity of the synthetic riboswitch shown in A. when cloned upstream of the IS10-lacZ gene fusion and expressed in E. coli. Right axis: β-galactosidase activity in the absence (open circle) or presence of theophylline (1-mM, closed circle). Activities are expressed in Miller units, and the standard errors of the mean are less than the diameters of the circles. Left axis: The activation ratio of the synthetic riboswitch (green bar), which is determined by taking the ratio of the activities in the presence and absence of theophylline.

C.) Sequence diagram of the randomized synthetic riboswitches. The aptamer is shown in green, the randomized regions in light blue, the ribosome binding site in pink, and the AUG start codon in peach. Theoretical library sizes are shown in the circle.

We used cassette-based PCR mutagenesis to create five different libraries in which the distance between the aptamer and the RBS was varied between 4 and 8 bases and the sequence was randomized fully (Figure 1C), because we previously observed that longer or shorter spacings resulted in poorly functioning switches.[11]

High-throughput Screen for Optimally Functioning Riboswitches

To screen the libraries, E. coli were transformed with plasmids harboring randomized sequences of a given length and were grown on selective agar plates in the presence of X-gal (the substrate for β-galactosidase), but in the absence of theophylline. Most (~99%) clones appeared blue, indicating that they were expressing β-galactosidase in the absence of theophylline. However, in all libraries, a number of colonies appeared white, suggesting little-to-no β-galactosidase expression. To identify whether these colonies harbored riboswitches that could activate protein translation in the presence of theophylline, we used a colony-picking robot to isolate the whitest colonies from each plate of approximately 4,000 colonies (Figure 2). These clones were inoculated into 96-well microtiterplates containing selective LB media. These cultures were grown overnight and were used to inoculate two new 96-well plates that either contained theophylline (0.5 mM) or did not. These plates were grown at 37 ºC with shaking for 2–2.5 hrs, and β-galactosidase activity was assayed using an adaptation of Miller’s method performed either by hand with a multi-channel pipettor, or using a robotic liquid-handling system.[29–31] Ratios of the Miller units for cultures grown in the presence of theophylline to those grown with or without theophylline (the “activation ratio”) were compared to identify functional switches.

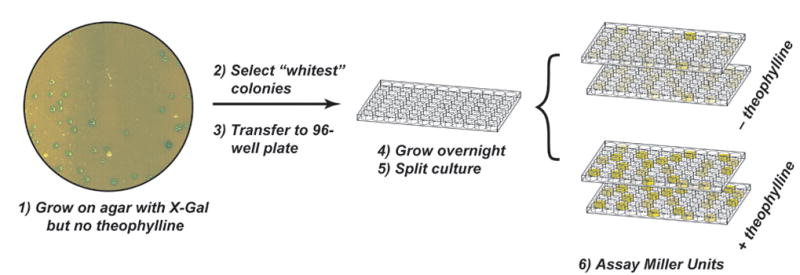

Figure 2. Diagram of the high throughput assay.

Candidate riboswitches are identified by plating cells onto selective media containing X-gal, but no theophylline. A robotic colony picker identifies the whitest colonies (lowest levels of β-galactosidase activity) and transfers the cells to a 96-well microtiterplate. The culture is grown overnight in selective media, split, and the clones are tested for β-galactosidase activity using the automated assay described in the text.

To validate the screen, we chose clones that displayed an activation ratio of greater than 2 and assayed them individually in larger cultures, but we discovered that less than half of these clones functioned as switches. Further analysis indicated that these irregularities were due to a number of factors, including small but significant differences in the growth rates and lysis efficiencies of the cells in the microtiterplates. To improve the accuracy of identifying functional synthetic riboswitches, we performed each assay in duplicate, and analyzed the data using an empirically derived procedure in which we retained candidates that: A) showed an activation ratio of greater than 2.0 in two separate determinations; B) displayed a minimum level of β-galactosidase activity in the presence of theophylline (an OD420 ≥ 0.04 in the Miller assay, regardless of cell density); C) grew normally relative to others in the plate (as represented by OD600); and D) showed consistent results between the two plates. This simple analysis significantly reduced the number of potential candidates, of which greater than 90% were confirmed as functional synthetic riboswitches when assayed individually in larger volumes of culture. For the small number of candidates that were not validated, sequencing often revealed mixed populations of plasmids that were likely introduced during colony picking and plating cells at lower densities minimized such events.

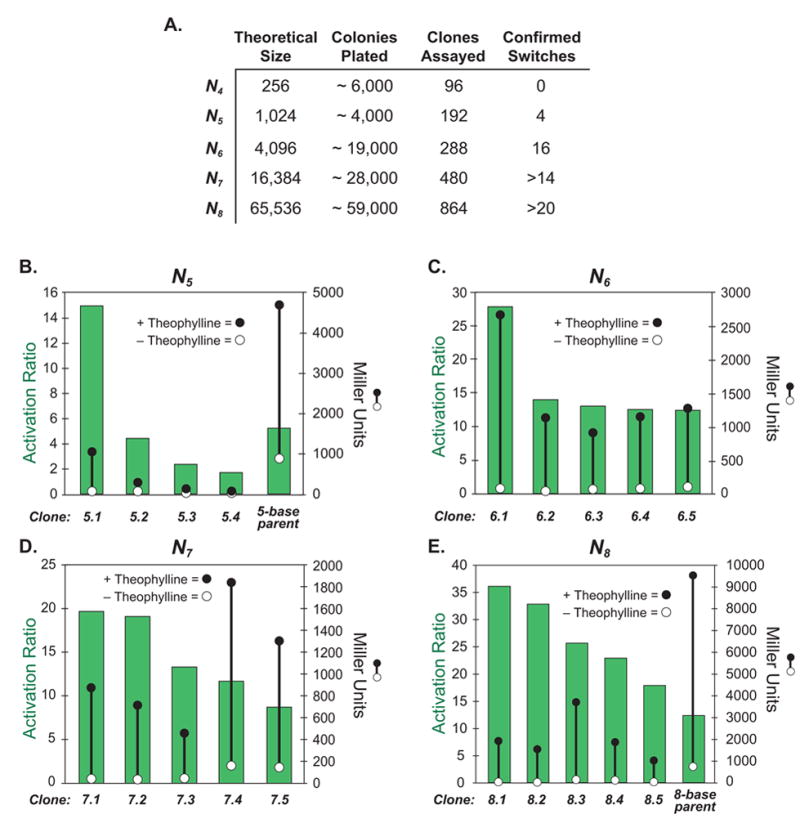

Figure 3 shows statistics for the libraries and the results from the top validated hits identified in each of these screens. For each sequence length, the absolute levels of β-galactosidase activity in the presence and absence of theophylline (1 mM) are plotted, as well as the ratio of these numbers (activation ratio) for the switches that displayed the highest activation ratios. From these data, it is clear that the high throughput screening method is capable of identifying riboswitches that display both low background levels of protein expression in the absence of ligand, and strong increases in the presence of the ligand. Indeed, the best clone identified (8.1) displays a 36-fold increase in protein expression in the presence of theophylline, and a very low level of expression in its absence. To put this in perspective, natural riboswitches that regulate protein translation (though, most of these switches repress protein translation) show repression ratios of about 100 in the presence of the ligand.[7] The discovery of switches that function within a factor of three of natural genetic regulatory elements that have evolved over considerably longer time periods suggests that this screening method is quite effective, and that creation of new synthetic riboswitches based on different aptamers may be straightforward.

Figure 3. Analysis of libraries and results from screens.

A.) Statistics for libraries assayed. B.-E.) Measures of the activities of the synthetic riboswitches identified in the high throughput screens. Each measurement is done in triplicate. For all panels: Right axis: β-galactosidase activity in the absence (open circle) or presence of theophylline (1-mM, closed circle). Activities are expressed in Miller units, and the standard errors of the mean are less than the diameters of the circles. Left axis: The activation ratio of the synthetic riboswitch (green bar), which is determined by taking the ratio of the activities in the presence and absence of theophylline.

Sequencing Suggests a Possible Mechanism of Action for Synthetic Riboswitch Function

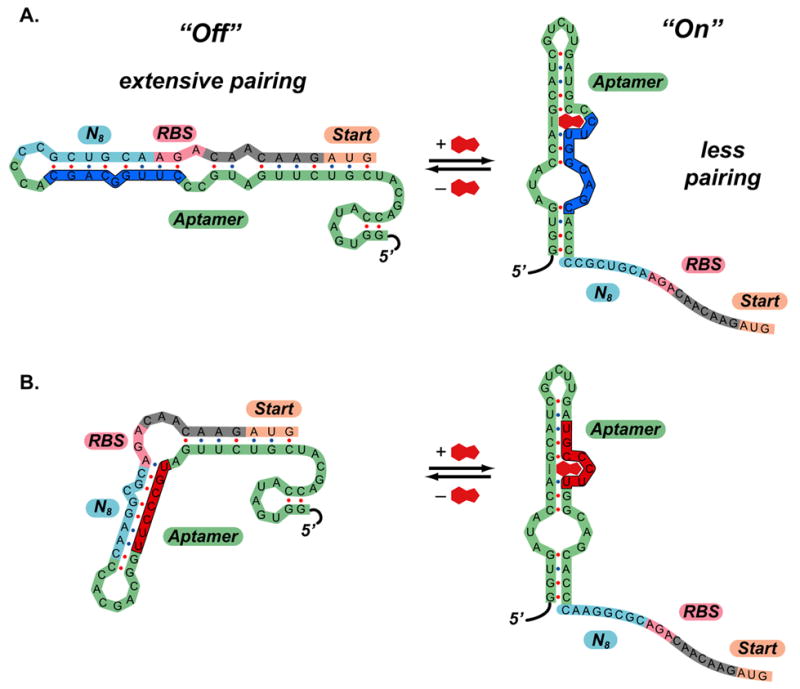

In addition to identifying synthetic riboswitches that display excellent performance characteristics, these screens provided a wealth of sequence information that allowed us to propose and test models for riboswitch function. Visual sequence analysis revealed several conserved or semi-conserved motifs that are complementary to different regions of the theophylline aptamer. Shown in Figure 4 are the mFold-predicted[32, 33] secondary structures of two of the new synthetic riboswitches in the region extending from the 5′-end of the aptamer to the 3′-end of the AUG start codon of the IS10-lacZ gene. On the left-hand side are the two minimum energy structures—in both cases, the bases between the aptamer and the RBS are paired with the aptamer sequence, suggesting that translation might be inhibited in the absence of the ligand. On the right-hand side of Figure 4, the experimentally determined secondary structure for the theophylline-binding aptamer[24–27] appears in the calculated structure and the RBS is not paired—in both cases, the calculated differences in free energy between the two structures are less than the free energy of theophylline binding (−9.2 kcal/mol),[24] suggesting that conversion between the structures is thermodynamically favorable in the presence of theophylline. All of the synthetic riboswitches identified in our screens can be folded into one of the two folding motifs (“blue” or “red”) shown in Figure 4 (sequences and their motifs are reported in the Supporting Information).

Figure 4. Predicted mechanisms of action of synthetic riboswitches.

A.) Predicted mechanism of action of clone 8.1. In the absence of theophylline (left), the 5′-region can adopt a highly folded structure that extensively pairs the region that includes ribosome binding site to part of the aptamer sequence (shown in dark blue). In the presence of theophylline (right), the secondary structure shifts, such that the ribosome binding site is exposed. The secondary structure shown for the theophylline aptamer predicted by mFold and is identical to the structure determined by NMR. B.) Predicted mechanism of action of clone 8.2. In this case, the region containing the ribosome binding site pairs to a different region of the aptamer in the “off” state (shown in red). This demonstrates that several motifs may function as synthetic riboswitches.

The folds in Figure 4 suggest a possible switching mechanism in which extensive pairing in the region near the ribosome binding site prevents translation of β-galactosidase in the absence of theophylline. Such behavior is consistent with the studies of de Smit and van Duin who demonstrated that secondary structure near the ribosome binding site dramatically reduces the translation of the mRNA downstream.[34–36] Theophylline binding (ΔGbind~−9.2 kcal/mol) could in principle drive the equilibrium toward the structures on the right, in which the known secondary structure of the aptamer is present [25] and the ribosome binding sites are unpaired, which would increase the efficiency of translation.

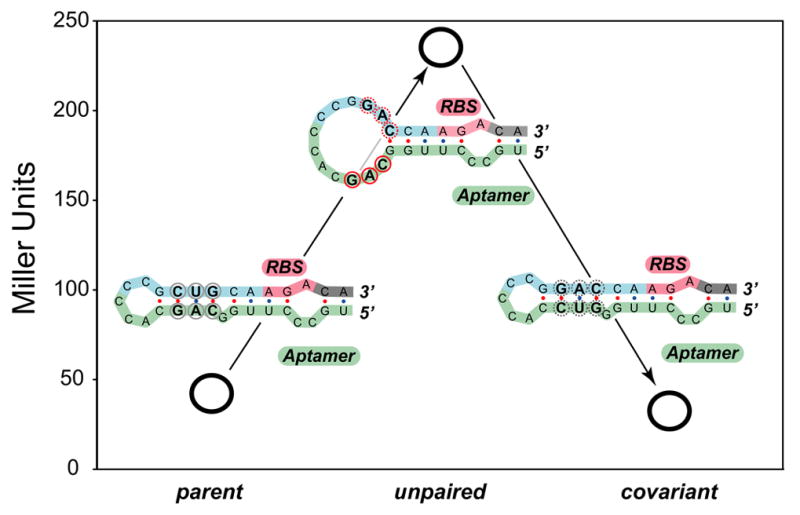

To test whether base-pairing between the aptamer and a region near the ribosome binding site was important for function, we performed covariance experiments in which we mutated these bases to disrupt the putative base-pairing (Figure 5). Removal of several putative base pairs in clone 8.1 increased β-galactosidase expression 5-fold in the absence of the ligand, while restoring the base pairing by mutating the aptamer sequence decreased the background level of β-galactosidase expression to its original level, consistent with the pairing hypothesis. Because these mutations also affect theophylline binding, these mutants were not active in the presence of theophylline.[26]

Figure 5. Results from covariance experiments.

β-galactosidase activities in the absence of theophylline (open circles) for the parent synthetic riboswitch (clone 8.1) (left), a triple mutant that unpairs the region near the ribosome binding site (center), and a mutant that restores the pairing (right). Activities are expressed in Miller units (shown on the left axis); the standard errors of the mean are less than the diameters of the circles. For each construct, the predicted secondary structure is shown in the region near the ribosome binding site. The parent and covariant maintain the pairing and show low background levels of β-galactosidase activity. The mutant unpairs this region and leads to leaky expression in the absence of theophylline.

In light of these results that suggest that pairing in the region between the aptamer and the ribosome binding site is important for riboswitch function, we revisited the activation data from our previously reported synthetic riboswitches.[11] In creating those switches, we did not explicitly engineer or screen for any particular sequence in this region. Reexamination of our previously reported riboswitch (Figure 1A) revealed that a 7 base sequence located 27 bases after the start codon of the IS10-lacZ reporter gene (UUUCUCU) is the precise reverse complement of the bases between the aptamer and the ribosome binding site. To test whether these regions pair to suppress gene expression in the absence of theophylline, we deleted the N-terminal IS10 fusion (pSALWT-ΔIS10). If bases within the IS10 sequence pair to suppress gene expression in the absence of theophylline, deleting this region should increase gene background levels of expression. Consistent with this model, deletion of the IS10 sequence increased the β-galactosidase activity in the absence of theophylline approximately 15-fold (from ~800 to over 12,000 Miller units), confirming that the previously reported synthetic riboswitches depended on the presence of the IS10 sequence to function.

The models proposed in Figure 4 predict that all of the necessary elements to control gene expression are located in the 5′-UTR, suggesting that the sequence of the downstream gene should not impact the function of the switch. To test this, we replaced the entire 5′-UTR of the “leaky” pSALWT-ΔIS10 construct with the 5′-UTR from clone 8.1. Gratifyingly, this construct (pSKD8.1-ΔIS10) behaved nearly identically to clone 8.1, with low background levels of β-galactosidase expression in the absence of theophylline, and a strong increase in β-galactosidase expression in the presence of theophylline (data not shown). Furthermore, we cloned the entire 5′-UTR from clone 8.1 upstream of several reporter genes that lack the N-terminal IS10 fusion, including gfp, dsRED, and cat. These switches all function well and do not depend on the sequence of the gene downstream (SAL, HKS, and JPG unpublished results). Taken together, these experiments and the covariance experiments above strongly implicate a functional role for the region between the aptamer and the RBS, and the results are consistent with the RNA folds shown in Figure 4.

A Model for Synthetic Riboswitch Function

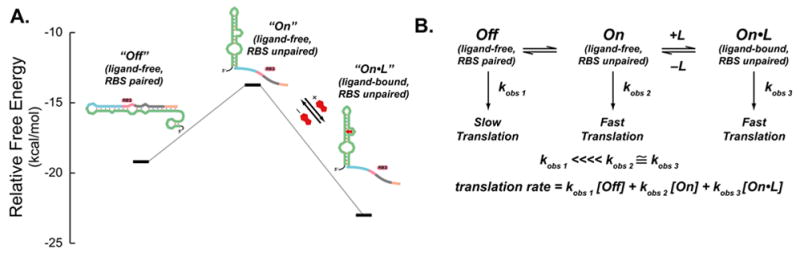

Our data suggest that these synthetic riboswitches display low background levels of translation in the absence of ligand and robust increases in the presence of the ligand for two reasons. The first is that in the absence of the ligand, the ribosome binding site is paired in such a way that translation is minimized. The second is that ligand binding drives the RNA to a conformation in which the RBS is unpaired. As described by de Smit and van Duin,[34–36] sequences with pairing near the ribosome binding site typically display reduced translation rates because the 30S subunit of the ribosome binds most efficiently to single-stranded regions of RNA. Since translation is the slow step in protein production, the position of a pre-equilibrium between RNA structures that have the ribosome binding site paired or unpaired will factor directly into the rate expression for protein synthesis. Sequences that strongly favor pairing of the ribosome binding site are likely to show minimal levels of protein translation in the absence of ligand, since translation is very inefficient when the RBS is paired. Even if such sequences equilibrate with higher-energy structures where the RBS is unpaired (and translation is efficient), the relative population of these high-energy states, and thus the overall translation rate, will be low. The relative stabilities of these structures will dictate the background levels of translation in the absence of the ligand. However, if addition of the ligand shifts the population of mRNAs to a structure(s) where many of the ribosome binding sites are unpaired, this model predicts robust increases in protein translation from these efficiently translated mRNAs.

Figure 6A. shows the predicted secondary structures and free energies of the region of the mRNA of clone 8.1 extending from the 5′-end of the aptamer to the 3′-end of the start codon. In the minimum energy structure (“Off”, left), the RBS is paired. In the middle is the lowest energy structure (ΔΔG=+5.5 kcal/mol; see the supporting information for the folding protocol) in which the ribosome binding site is predicted to be unpaired (“On”); this is also the lowest energy structure in which the secondary structure of the aptamer is present. On the right is the same calculated fold, but the free energy has been lowered by 9.2 kcal/mol, the experimentally-determined free energy of theophylline binding (“Off•L”).

Figure 6. Model for synthetic riboswitch function.

A.) Predicted structures and free energies of a portion of the 5′-region of clone 8.1 determined by mFold. To represent the free energies of the bound structures, we added the experimentally determined free energy of theophylline binding (−9.2 kcal/mol) to the free energy of the un-liganded structure determined by mFold since the secondary structure of the mTCT-8-4 aptamer does not change upon ligand binding.

B.) Kinetic model for synthetic riboswitch function. In the “Off” state, the ribosome binding site is paired and translation is slow (represented by the pseudo-first order rate constant k1 obs, which accounts for ribosome binding and translation). The “Off” state is proposed to be in equilibrium with the ligand-free “On” state, in which the ribosome binding site is unpaired and translation is relatively fast (represented by the pseudo-first order rate constant k2 obs, which is much greater than k1 obs). Since this state is not highly populated, background translation is minimal. Addition of ligand (L) shifts the equilibrium to the ligand-bound “On” state, in which the ribosome binding site is unpaired and translation is relatively fast (represented by the pseudo-first order rate constant k3 obs, which is also much greater than k1 obs).

An equilibrium model predicts that in the absence of the ligand, the majority of the RNA population adopts the “Off” structure in which the RBS is paired because the “On” structure is significantly uphill in free energy. Addition of theophylline provides the thermodynamic driving force to shift the equilibrium toward the “On•L” structure. These observations can be represented in the model shown in Figure 6B, where the pseudo-first order rate constants (kobs 1, kobs 2, and kobs 3) include the rates of ribosome binding and the initiation of translation and the concentration of the 30S ribosomal subunit. The studies of de Smit and van Duin[34–36] predict that the translation efficiency from the “Off” structure, in which the ribosome binding site is paired, would be significantly lower than the efficiency from the structures in which the RBS is unpaired (“On” and “On•L”), thus kobs 1 ⋘ kobs ≈ kobs 3. Thus, in the absence of ligand, the overall translation rate would be low, and the rate would increase in the presence of the ligand.

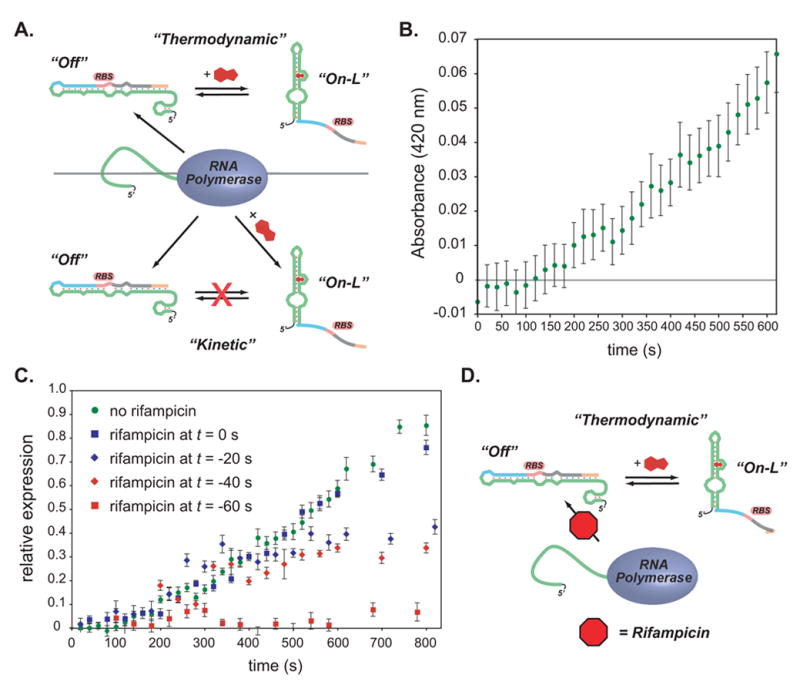

While this model qualitatively fits our experimental observations, determining accurate rate constants and mRNA concentrations in vivo is very challenging. Nevertheless, we can test elements of the model, such as the ability of RNA structures to equilibrate in the presence of the ligand. Demonstrating that an mRNA transcript can undergo a ligand-inducible shift from an untranslated state into a translated state in vivo would provide evidence for the equilibrium model proposed above, and would also argue against a kinetic model, in which the committed step for translation occurs during transcription (i.e. a transcript is translated only if the appropriate ligand is present at the time of transcription; Figure 7A).[37, 38]

Figure 7. Experiments to determine switching mechanism.

A.) top: A thermodynamic model for riboswitch function. Newly synthesized RNA adopts a folded conformation that prevents translation (“Off”). Addition of theophylline can drive the conformation to the “On-L” conformation. bottom: A kinetic model in which a newly synthesized RNA adopts either an “Off” or an “On-L” conformation depending on whether ligand is present during transcription, however the “Off” and “On-L” conformations do not equilibrate.

B.) Time course for appearance of β-galactosidase activity (measured by ONPG hydrolysis) for clone 8.1. Theophylline was added at t = 0 to a final concentration of 3 mM; significant activity appears at 200 s.

C.) Time course for appearance of β-galactosidase activity (measured by ONPG hydrolysis) for clone 8.1. Theophylline was added at t = 0 to a final concentration of 3 mM; rifampicin was added at the times shown in the legend. Rifampicin does not eliminate β-galactosidase activity when added up to 40 s prior to the addition of theophylline, supporting the thermodynamic model shown in A.) and D.) in which theophylline can induce expression even in the absence of active transcription.

To test these models, E. coli that were constitutively transcribing a riboswitch-controlled lacZ gene were grown in the absence of theophylline. Theophylline was added and the β-galactosidase expression at various time points was assayed using Miller’s method (Figure 7B). β-galactosidase activity (as measured by A420) first appears approximately 200 seconds after the addition of theophylline and continues to increase at a steady rate. During the 200 seconds before β-galactosidase activity appears, several events must occur: 1) theophylline must enter the cell; 2) it must bind to the mRNA; 3) it must induce switching; 4) the ‘switched’ mRNA must be translated; and 5) β-galactosidase must fold and become active. Liang et al. have shown β-galactosidase activity in E. coli appears within 60 seconds upon using IPTG to initiate transcription of lacZ.[39] Their results show that transcription rate of lacZ must be at least 57 nt/s (3420 nt/60 s), and that the subsequent acts of translation, folding, and appearance of β-galactosidase activity must collectively take less than 60 seconds.[39] After accounting for the 60 s required for translation, folding, and the appearance of enzymatic activity, the fact that we do not observe β-galactosidase activity until 200 s after theophylline addition suggests that collectively theophylline entry, binding, and switching may take up to 140 s. Although this delay could be consistent with a kinetic barrier for interconversion between a non-translatable mRNA and a translatable mRNA, we cannot yet determine whether such conformational changes are responsible for the switching behavior.

An alternative to a theophylline-driven equilibrium model is a “kinetic” mechanism whereby the fate of an mRNA is determined at the time of transcription. Much of the data thus far can also be explained in terms of a co-transcriptional kinetic model in which the majority of the mRNA pool folds into a non- or weakly-translatable conformation when theophylline is not present (e.g. the “Off” conformation shown in Figure 7A). If theophylline can induce some fraction of the mRNA to fold into the highly translatable “On-L” conformation, theophylline-dependent activation of translation could occur regardless of whether the translatable and non-translatable mRNA conformations can interconvert. Given that A) lacZ transcription is fast (~60 nt/s)[39]; B) both mRNA folding and translation occur co-transcriptionally in E. coli; C) the entire “functional unit” of the riboswitch is located within the first 100 transcribed bases; and D) the proposed “On” and “Off” conformations are both small hairpins, it is extremely likely that the fate (translatability) of an mRNA is determined within seconds of the initiation of transcription. As such, theophylline would have to be present during transcription for β-galactosidase activity to be observed.

To test whether β-galactosidase expression is dependent on the presence of theophylline while transcription is active, we used the antibiotic rifampicin to halt transcription and asked whether subsequent addition of theophylline could induce β-galactosidase expression. Rifampicin prevents RNA polymerase from entering the elongation phase following the initiation of transcription, but it has no effect on RNA polymerase once it has reached the elongation phase.[39] The quick action of rifampicin (~5 s), coupled with the fast elongation rate of E. coli RNA polymerase (~60 nt/sec),[39] suggests that within 10 s of rifampicin addition, no new transcripts are being produced and any elongating transcripts are ~100 nt beyond the 5′-UTR.

Figure 7C shows the theophylline-induced expression of β-galactosidase from cultures harboring switch 8.1 in which rifampicin was added 0, 20, 40, or 60 s prior to the addition of theophylline. While adding rifampicin 20 or 40 s prior to adding theophylline reduces the overall level of β-galactosidase activity, as would be expected from the inhibition of mRNA synthesis, the onset of β-galactosidase activity occurs at the same time (~200 s) as it does in the absence of rifampicin. Assuming that rifampicin acts within 5 s and that E. coli RNA polymerase transcribes mRNA at 60 nt/s,[39] by adding rifampicin 40 s prior to theophylline, no new transcripts should be synthesized, and any elongating transcripts should be >1800 nt long, far beyond the 100 nt 5′-UTR containing the riboswitch, at the time that theophylline is added. Though we cannot easily determine how quickly theophylline enters the cell and reaches an effective concentration, we can consider 2 limiting scenarios: theophylline enters essentially immediately, or theophylline entry is delayed by up to 200 s. If theophylline enters immediately, the delay before the onset of β-galactosidase activity is difficult to explain, as the co-transcriptional model predicts that the “decision” to translate occurs early in the process of transcription; since translation and folding occur within 60 s, leaving a 140 s gap. If theophylline entry is slow (up to 140 s), the co-transcriptional model becomes even less tenable because at +140 s, all transcripts should be completed, regardless of the time of addition of rifampicin. The fact that β-galactosidase activity continues to increase steadily long after the addition of theophylline, and > 300 seconds after the addition of rifampicin (Figure 7C), argues against a co-transcriptional model for the activation of expression and is more consistent with a model in which theophylline induces a conformational change in an existing mRNA (Figure 7D).

Since the data support an equilibrium model in which theophylline induces conformational changes, one might expect that ligand-dependent changes could be observed through RNA footprinting studies. To test this possibility, we performed in vivo footprinting experiments using the SHAPE method developed by Weeks and co-workers.[40] In the SHAPE method, N-methylisatoic anhydride (NMIA) modifies the 2′-OH of RNA depending on the local nucleotide flexibility. [40] These modifications of an RNA template cause the enzyme reverse transcriptase to pause and dissociate, leading to truncations at the site immediately 3′-to the modified ribose. By comparing the products of a reverse-transcription reaction against a known sequence standard using gel electrophoresis, one can map the location of modifications, as well as the extent of modification.

We added NMIA to cells harboring a synthetic riboswitch that were grown in the presence or absence of 1 mM theophylline. The modified total RNA was extracted and used as a template for reverse transcription. The transcription reactions were separated by gel electrophoresis and the pausing due to NMIA modification in the presence and absence of ligand was analyzed. Though we observed NMIA modification of RNA that was not present in an untreated control, we were not able to visualize substantial differences in NMIA modification between cells grown in the presence or absence of theophylline.

SHAPE experiments integrate the total RNA population, not just the fraction of mRNAs that are potentially translatable, and it may be difficult to detect a small increase in translatable mRNAs against a large background of non-translatable mRNAs. To assess the fraction of mRNAs that are translating in vivo, we compared the levels of β-galactosidase expression between a riboswitch-containing construct (clone 8.1) and a construct that shared the same ribosome binding site from 8.1, but lacked the aptamer. The construct lacking the aptamer expressed approximately 6-times more β-galactosidase than the riboswitch containing construct grown in the presence of 1 mM theophylline. This is consistent with the idea that theophylline induces translation of ~16% of the transcripts, but that ~84% may remain inactive. Since SHAPE (and other methods that integrate results over entire populations) cannot distinguish between translating and non-translating mRNAs, the majority of labeled RNA would be expected to be the non-translating, and a small increase in translating RNAs will likely not be visible. While other in vitro experiments such as nuclease digestion under thermodynamically controlled conditions (renaturing, long time-scales) might glean further structural information, it is not immediately clear that this information would be directly relevant to the actual behavior inside the cell. Finally, we note that for an “on” switch, there is no a priori reason to assume that full activation of translation is necessary or even desirable for function in either synthetic or natural riboswitches. Indeed, we have observed riboswitches that activate more fully (e.g. the parent switch in Figure 3E), but such switches may face a trade-off between leaky expression and high-absolute levels of activation.

Possible Design Implications for Synthetic Riboswitches

While the generality of this equilibrium model will be investigated in future studies, in its current form, the model may provide guidelines for the design of synthetic riboswitches that activate protein translation. In particular, the model suggests that it will be critical to balance the relative free energies of “off state”, the ligand-free “on state”, and the ligand-bound “on state”. Since the energy differences of the ligand-free “on state” and the ligand-bound “on state” are dictated by the free energy of ligand binding to the aptamer, this puts thermodynamic constraints on potential structures for the “off state”. If the free energy of the “off state” is close to that of the ligand-free “on state” (and there is interconversion), background translation in the absence of the ligand will be high. However, if the “off state” is very stable, binding of ligand may not result in a sufficient population of the ligand-bound “on state” to allow translation, even if this state is highly translatable. We anticipate that this model may help guide the design of future synthetic riboswitches.

Possible Evolutionary Implications for Natural Riboswitches

Our results show that beginning with an aptamer sequence that recognizes a small molecule, it is relatively straightforward to create synthetic riboswitches. Indeed, we have discovered a variety of high-performing synthetic riboswitches where both the length and composition of the sequence between the aptamer and the ribosome binding site vary considerably. Furthermore, we have shown two new functional motifs where the bases between the aptamer and the ribosome binding site pair to distinct regions of the aptamer, and retrospective analysis of a previously reported synthetic riboswitch reveals a third motif where these bases pair to part of the coding sequence to repress translation in the absence of the ligand. Taken together, our results show that there are many straightforward ways to generate synthetic riboswitches by inserting an aptamer sequence into the 5′-UTR of a gene. Via relatively few base changes, the dynamic ranges of these switches can be improved dramatically to give sensitive ligand-dependent genetic control elements. It has been suggested that natural riboswitches may be molecular fossils from an RNA world,[7] where RNA sequences that once served to bind to ligands (perhaps as cofactors for RNA catalysis), have since been co-opted for the purpose of gene regulation. Our results show that it is relatively straightforward on the laboratory timescale to convert an aptamer into a synthetic riboswitch. We suggest that using similar mechanisms, Nature may have evolved riboswitches from pre-existing aptamers.

Significance

Riboswitches are RNA-based genetic control elements that activate or repress gene expression in a small molecule-dependent fashion without the need for proteins. The ability to create synthetic riboswitches that control gene expression in response to any desired small molecule could enable the development of sensitive genetic screens and selections to detect the presence of small molecules, as well as the creation of designer genetic control elements for studying cell function or conditional gene therapy. Riboswitches require an aptamer to recognize the desired molecule, and a mechanism for converting this sensing event into a change in gene expression. While methods to discover aptamers that selectively bind small molecules are well-established, methods of converting these aptamers to synthetic riboswitches that function optimally in cells are not. We have presented an automated high throughput screening method that identifies synthetic riboswitches that show extremely low background levels of gene expression in the absence of ligand, and robust increases in expression in the presence of the desired ligand. These synthetic riboswitches not only show superior performance relative to previously reported switches, but also compare favorably to natural riboswitches. Sequence information allowed us to propose and test a model for riboswitch function that explains the mechanism of action for these and previously described synthetic riboswitches. Furthermore, we have proposed a simple model for synthetic riboswitches that activate protein translation that may guide future experiments.

Our results show that beginning with a known aptamer, it is straightforward to create distinct families of synthetic riboswitches, which is consistent with the idea that natural riboswitches may have evolved from small molecule-binding aptamers that were retained from an RNA world and subsequently recruited to become genetic regulation elements. We anticipate that this high throughput method will be generally useful for converting in vitro selected aptamers into robust performing synthetic riboswitches.

Experimental Procedures

General Considerations

All plasmid manipulations utilized standard cloning techniques.[41] All constructs have been verified by DNA sequencing at the NSF-supported Center for Fundamental and Applied Molecular Evolution at Emory University. Purifications of plasmid DNA, PCR products, and enzyme digestions were performed using kits from Qiagen. Theophylline, o-nitrophenyl-β-D-galactopyranoside (ONPG), ampicillin, and chloramphenicol were purchased from Sigma. X-gal was purchased from US Biological. Synthetic oligonucleotides were purchased from IDT. All experiments were performed in E. coli TOP10 F′ cells (Invitrogen) cultured in media obtained from EMD Bioscience.

Construction of Randomized Libraries

Libraries were constructed using oligonucleotide-based cassette mutagenesis. Mutagenic primers with degenerate regions were designed to create cassettes with randomized sequences of appropriate lengths between the mTCT8-4 theophylline aptamer[24] and the RBS of the IS10-LacZ reporter gene. Full descriptions of the mutagenesis strategies, primer sequences, and plasmid features are available in the Supporting Material

Library screens

Library transformations were plated on large (241 mm x 241 mm) bioassay trays from Nalgene containing LB/agar (300 mL) supplemented with ampicillin (50 μg/mL) and X-Gal (25 mg dissolved in 4.0 mL of dimethyl formamide, final concentration 0.008%). Cells were plated to achieve a final density of ~4,000 colonies/plate. Cells were grown for 14 h at 37 °C, followed by incubation at 4 °C until blue color was readily visible.

The whitest colonies from each plate were picked using a Genetix QPix2 colony picking robot and were inoculated in a 96-well microtiter plate (Costar) which contained LB-media (200 μL/well) supplemented with ampicillin (50μg/mL). The plate was incubated overnight at 37 ºC with shaking (180 rpm). The following day, four 96-well plates (two sets of two) were inoculated using 2 μL of the overnight culture. The first set of plates contained 200 μL of LB supplemented with ampicillin (50μg/mL). The second set of plates contained 200 μL of LB supplemented with both ampicillin (50μg/mL) and theophylline (0.5 mM). Plates were incubated for approximately 2.5 hrs at 37 ºC with shaking (210 rpm) to an OD600 of 0.085–0.14 as determined by a Biotek microplate reader. These values correspond to an OD600 of 0.3–0.5 with a 1 cm path length cuvette. A high-throughput microtiterplate assay for β-galactosidase activity was adapted from previously described methods.[29–31] Cultures were lysed by adding Pop Culture® solution (Novagen, 21 μL, 10:1, Pop Culture : lysozyme (4 U/mL)), mixed by pipetting up and down, and allowed to stand at room temperature for 5 min. In a fresh plate, 15 μL of lysed culture was combined with Z-buffer (132.25 μL, 60 mM Na2HPO4, 40 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO4, 50 mM β-mercaptoethanol, pH 7.0). This was followed by addition of ONPG (29 μL, 4 mg/mL in 100 mM NaH2PO4). ONPG was allowed to hydrolyze for approximately 20 min or until faint yellow color was observed. The reaction was quenched by the addition of Na2CO3 (75 μL of a 1 M solution). The length of time between substrate addition and quenching was recorded and the OD420 for each well was determined. The Miller units were calculated using the following formula: Miller units = OD420/(OD600 × hydrolysis time × (volume of cell lysate/total volume)). Ratios of the Miller units for cultures grown in the presence or absence of theophylline represent an “activation ratio”. The initial pool of candidate switches comprised clones that showed an activation ratio of greater than 2.0 in two separate determinations. Candidates that did not display a minimum activity in the presence of theophylline (an OD420 ≥ 0.04) in either determination were eliminated from consideration. As a final check, we visually inspected the data for aberrations, such as cultures that grew especially slowly or quickly (as represented by OD600), or for cultures with dramatically different results between the two plates. Clones that were identified as potential switches were subcultured and assayed as previously described.

Rifampicin Assay

An aliquot of a saturated overnight culture (500 μL) was used to inoculate 50 mL of LB supplemented with ampicillin (50 μg/mL). The fresh culture was grown with shaking (300 rpm, 37 ºC) to an OD600 of 0.4–0.5 (approx 2.75 h). The culture was split into two 16.6 mL fractions. Theophylline (50 mg/mL in DMSO, warmed to 37 ºC) and rifampicin (50 mg/mL in DMSO) were added as appropriate to one of the cultures such that the final concentrations were 3.0 M theophylline, 250 μg/mL rifampicin; the other culture was used as a control. Aliquots of the cultures (4 x 100 μL each) were collected at 20, 40, or 100 s intervals using a Freedom-EVO liquid handling system (TECAN) and were transferred to individual wells of a 96-well microtiter plate that were pre-filled with Pop Culture® (10 μL). A 30μL aliquot from each well of lysed cells was added to 119 μL of Z-buffer in a microtiter plate (see above). ONPG (29 μL, 4 mg/mL in 100 mM NaH2PO4) was added and was allowed to hydrolyze for 1 hr at 30 ºC, followed by quenching with Na2CO3 (75 μL of a 1 M solution). The OD420 for each well was determined.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Research Corporation, the Seaver Institute, the Arnold and Mabel Beckman Foundation, the NIH (R01-GM074070), and Emory University for financial support. S.A.L. is an NSF-PRISM Fellow. S.K.D. is grateful to Emory University for providing a George W. Woodruff Fellowship. J.P.G. is a Beckman Young Investigator. We thank Pavan Bang for technical assistance, Professor Dale Edmondson for helpful discussions, and Drs. Doug Grubb and Wayne Patrick for critical readings of the manuscript. DNA sequencing was performed at the NSF-supported Center for Fundamental and Applied Molecular Evolution (NSF-DBI-0320786).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Winkler WC, Breaker RR. REGULATION OF BACTERIAL GENE EXPRESSION BY RIBOSWITCHES. Annual Review of Microbiology. 2005;59:487–517. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.59.030804.121336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nudler E, Mironov AS. The riboswitch control of bacterial metabolism. Trends Biochem Sci. 2004;29:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vitreschak AG, Rodionov DA, Mironov AA, Gelfand MS. Riboswitches: the oldest mechanism for the regulation of gene expression? Trends Genet. 2004;20:44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2003.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tucker BJ, Breaker RR. Riboswitches as versatile gene control elements. Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 2005;15:342. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mironov AS, Gusarov I, Rafikov R, Lopez LE, Shatalin K, Kreneva RA, Perumov DA, Nudler E. Sensing small molecules by nascent RNA: a mechanism to control transcription in bacteria. Cell. 2002;111:747–756. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01134-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nahvi A, Sudarsan N, Ebert MS, Zou X, Brown KL, Breaker RR. Genetic Control by a Metabolite Binding mRNA. Chem Biol. 2002;9:1043–1049. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(02)00224-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Winkler W, Nahvi A, Breaker RR. Thiamine derivatives bind messenger RNAs directly to regulate bacterial gene expression. Nature. 2002;419:952–956. doi: 10.1038/nature01145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Winkler WC, Cohen-Chalamish S, Breaker RR. An mRNA structure that controls gene expression by binding FMN. Proc Natl Acad Sci (USA) 2002;99:15908–15913. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212628899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sudarsan N, Wickiser JK, Nakamura S, Ebert MS, Breaker RR. An mRNA structure in bacteria that controls gene expression by binding lysine. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2688–2697. doi: 10.1101/gad.1140003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thore S, Leibundgut M, Ban N. Structure of the eukaryotic thiamine pyrophosphate riboswitch with its regulatory ligand. Science. 2006;312:1208–1211. doi: 10.1126/science.1128451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Desai SK, Gallivan JP. Genetic Screens and Selections for Small Molecules Based on a Synthetic Riboswitch That Activates Protein Translation. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:13247–13254. doi: 10.1021/ja048634j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grate D, Wilson C. Inducible regulation of the S. cerevisiae cell cycle mediated by an RNA aptamer-ligand complex. Bioorg Med Chem. 2001;9:2565–2570. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(01)00031-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harvey I, Garneau P, Pelletier J. Inhibition of translation by RNA-small molecule interactions. RNA. 2002;8:452–463. doi: 10.1017/s135583820202633x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suess B, Fink B, Berens C, Stentz R, Hillen W. A theophylline responsive riboswitch based on helix slipping controls gene expression in vivo. Nucl Acids Res. 2004;32:1610–1614. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suess B, Hanson S, Berens C, Fink B, Schroeder R, Hillen W. Conditional gene expression by controlling translation with tetracycline-binding aptamers. Nucl Acids Res. 2003;31:1853–1858. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Werstuck G, Green MR. Controlling Gene Expression in Living Cells Through Small Molecule-RNA Interactions. Science. 1998;282:296–298. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5387.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roth A, Breaker RR. Selection in vitro of allosteric ribozymes. Methods Mol Biol. 2004;252:145–164. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-746-7:145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buskirk AR, Landrigan A, Liu DR. Engineering a ligand-dependent RNA transcriptional activator. Chem Biol. 2004;11:1157–1163. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim DS, Gusti V, Pillai SG, Gaur RK. An artificial riboswitch for controlling pre-mRNA splicing. RNA. 2005;11:1667–1677. doi: 10.1261/rna.2162205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bayer TS, Smolke CD. Programmable ligand-controlled riboregulators of eukaryotic gene expression. Nat Biotech. 2005;23:337. doi: 10.1038/nbt1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Isaacs FJ, Dwyer DJ, Ding C, Pervouchine DD, Cantor CR, Collins JJ. Engineered riboregulators enable post-transcriptional control of gene expression. Nat Biotech. 2004;22:841. doi: 10.1038/nbt986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Isaacs FJ, Dwyer DJ, Collins JJ. RNA synthetic biology. Nat Biotech. 2006;24:545–554. doi: 10.1038/nbt1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Isaacs FJ, Collins JJ. Plug-and-play with RNA. Nat Biotech. 2005;23:306–307. doi: 10.1038/nbt0305-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jenison RD, Gill SC, Pardi A, Polisky B. High-resolution molecular discrimination by RNA. Science. 1994;263:1425–1429. doi: 10.1126/science.7510417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zimmermann GR, Jenison RD, Wick CL, Simorre JP, Pardi A. Interlocking structural motifs mediate molecular discrimination by a theophylline-binding RNA. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4:644–649. doi: 10.1038/nsb0897-644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zimmermann GR, Shields TP, Jenison RD, Wick CL, Pardi A. A semiconserved residue inhibits complex formation by stabilizing interactions in the free state of a theophylline-binding RNA. Biochemistry. 1998;37:9186–9192. doi: 10.1021/bi980082s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zimmermann GR, Wick CL, Shields TP, Jenison RD, Pardi A. Molecular interactions and metal binding in the theophylline-binding core of an RNA aptamer. RNA. 2000;6:659–667. doi: 10.1017/s1355838200000169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Boer HA, Comstock LJ, Vasser M. The tac promoter: a functional hybrid derived from the trp and lac promoters. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:21–25. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.1.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jain C, Belasco JC. Rapid genetic analysis of RNA-protein interactions by translational repression in Escherichia coli. Methods in Enzymology. 2000;318:309–332. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)18060-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bignon C, Daniel N, Djiane J. Beta-Galactosidase and Chloramphenicol Acetyl Transferase Assays in 96-Well Plates. Biotechniques. 1993;15:243–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Griffith KL, Wolf JRE. Measuring [beta]-Galactosidase Activity in Bacteria: Cell Growth, Permeabilization, and Enzyme Assays in 96-Well Arrays. Bioch Biophys Res Comm. 2002;290:397. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.6152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mathews DH, Sabina J, Zuker M, Turner DH. Expanded sequence dependence of thermodynamic parameters improves prediction of RNA secondary structure. J Mol Biol. 1999;288:911. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zuker M. Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucl Acids Res. 2003;31:3406–3415. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Smit MH, van Duin J. Secondary Structure of the Ribosome Binding Site Determines Translational Efficiency: A Quantitative Analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci (USA) 1990;87:7668–7672. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.19.7668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Smit MH, van Duin J. Control of translation by mRNA secondary structure in Escherichia coli. A quantitative analysis of literature data. J Mol Biol. 1994;244:144–150. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Smit MH, van Duin J. Translational initiation on structured messengers. Another role for the Shine-Dalgarno interaction. J Mol Biol. 1994;235:173–184. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(05)80024-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wickiser JK, Cheah MT, Breaker RR, Crothers DM. The kinetics of ligand binding by an adenine-sensing riboswitch. Biochemistry. 2005;44:13404–13414. doi: 10.1021/bi051008u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wickiser JK, Winkler WC, Breaker RR, Crothers DM. The speed of RNA transcription and metabolite binding kinetics operate an FMN riboswitch. Mol Cell. 2005;18:49–60. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liang ST, Ehrenberg M, Dennis P, Bremer H. Decay of rplN and lacZ mRNA in Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1999;288:521–538. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Merino EJ, Wilkinson KA, Coughlan JL, Weeks KM. RNA structure analysis at single nucleotide resolution by selective 2′-hydroxyl acylation and primer extension (SHAPE) J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:4223–4231. doi: 10.1021/ja043822v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sambrook J, Russell DW. Molecular cloning : a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2001. pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.