Environmental influences on epigenetics are important for understanding the mechanisms and inheritance of biological variation. Some of the best models for mammalian epigenetics are the yellow alleles of agouti in mice. Alleles such as Avy produce readily distinguished agouti, yellow, and mottled coat-color epigenetic phenotypes. Dietary and genetic variations during development affect the epigenetic phenotypes of offspring (1, 2). Little is known regarding the gestational timing of dietary treatments to affect epigenetics. Although the epigenetic phenotype is partially maternally, and grandmaternally, inherited (1, 3, 4), transgenerational effects of grandmaternal diets have not been reported. In this issue of PNAS, Cropley et al. (5) report the effects of specific timing of maternal dietary methyl supplementation on the coat color of offspring. Surprisingly, they find that maternal supplementation only during midgestation substantially affects offspring coat color. Importantly, they also find that this effect is inherited by the next generation, presumably through germ-line modifications during grandmaternal supplementation.

Mice carrying the Avy or Aiapy agouti allele, combined with a null allele (called a), produce a spectrum of epigenetic variation. This spectrum includes coat color, which varies from entirely yellow mice, through an array of mottled varieties, to fully agouti mice (1, 6). Yellow and mottled mice are obese and are prone to diabetes and cancer, in contrast to fully agouti mice, known as pseudoagoutis, which are lean and nondiabetic (7, 8). There is a high correlation between DNA methylation of the Avy or Aiapy alleles and the proportion of agouti in the coats of these mice (2, 4, 6, 9, 10). This spectrum of epigenetic variation is shifted toward agouti (and away from yellow) by maternal dietary methyl supplementation (1, 9, 10).

In gestation, much of the genomewide demethylation of DNA occurs between fertilization and preimplantation (day 4.5). This stage is followed by a wave of methylation after implantation (11). Recent data suggest that Avy may follow similar timing of demethylation and methylation (12). However, Avy silencing is passed from dam to offspring in a substantial minority of the population (1, 3, 4), indicating that DNA methylation, histone modification(s) (13), or other epigenetic mechanism(s) maintain some Avy silencing throughout gestation.

DNA methylation is established and maintained by DNA methyltransferases (Dnmts). Studies of the oocyte and somatic forms of Dnmt1 suggest that most times of gestation (early and mid-to-late gestation) may be important for Aiapy silencing (2). These previous Avy and Aiapy studies do not address other silencing mechanisms such as histone methylation, which also may be affected by maternal diet.

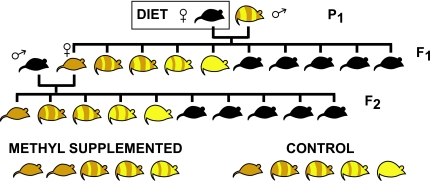

Because the full mechanism of silencing is not established and because diet studies often supplement throughout pregnancy, the timing of supplementation needed for Avy silencing is undefined. Cropley et al. (5) supplemented pregnant dams between embryonic day 8.5 (E8.5) and E15.5 and compared this with supplementation from 2 weeks before pregnancy until birth. Gestation is normally 21 days in mice. Cropley et al. (5) mated a/a dams with Avy/a sires (P1) and scored offspring (F1) phenotypes (Fig. 1). They found that the proportion of agouti coat was higher in offspring (F1) from supplemented dams than from control diet dams. Their results show that maternal (P1) diet affects Avy silencing in developing fetuses after E8.5 and that supplementation during early embryogenesis is not necessary.

Fig. 1.

Experimental transgenerational breeding design of Cropley et al. (5). Female mice (a/a, black) are mated with male mice (Avy/a, pseudoagouti or mottled) in the P1 generation. Female mice are fed either a control or a methyl-supplemented diet during midgestation in the P1 generation. All other mice receive control diet. Pseudoagouti dams (Avy/a) of the F1 generation are mated with a/a, black sires to produce the F2 generation. Both the F1 and F2 generation mice from methyl-supplemented P1 dams show a greater degree of agouti coat color than F1 and F2 generation mice from control diet P1 dams. The distribution of phenotypes shown is only to illustrate the trend. See Cropley et al. (5) for phenotype percentages in each population.

The degree of change in offspring phenotype was similar between dams supplemented throughout gestation or just from E8.5 to E15.5. However, an effect at midgestation does not rule out effects at other times in gestation. It may be that epigenetics can be influenced at a variety of times in gestation.

Maternal inheritance of the coat-color phenotype in mice carrying the Avy allele was first reported by Wolff in 1978 (3) based on the observation that agouti dams were more likely to produce agouti offspring than were yellow dams. This pattern was attributed to metabolic differences in the intrauterine environment (3). Morgan et al. (4) showed that maternal inheritance of the coat-color phenotype is most consistent with inheritance of an epigenetic mark, a silenced Avy allele. They did not see an effect of metabolism on Avy silencing.

There is also a grandmaternal effect on inheritance. That is, when mother and grandmother are fully agouti, a higher proportion of offspring have fully agouti coats than when the grandmother has a mottled or yellow phenotype (4). However, the effect of grandmaternal methyl supplementation was unknown. To answer this question, Cropley et al. (5) mated a/a dams with Avy/a sires (P1), supplemented the pregnant dams between E8.5 and E15.5, and then, without further supplementation, mated their pseudoagouti female offspring (F1) to a/a sires (Fig. 1). They found that the proportion of agouti coat was higher in offspring (F2) from supplemented grandmothers than from control diet grandmothers. Their results suggest that maternal (P1) diet affects the germ line developing in the F1 generation and that these effects carry through to the postnatal F2 offspring. These results demonstrate a transgenerational effect of maternal diet on the F2 generation, and they suggest a mechanism, namely modification of the F1 germ line. The degree of change in offspring phenotype was similar in the F1 and F2 generations, indicating that germ-line Avy silencing may be well maintained through gametogenesis, fertilization, and development. Theirs is the first demonstration that a germ-line epigenetic change can be induced at a specific gene. They provide a mechanism for transgenerational epigenetic effects.

The molecular mechanism for diet-induced germ-line silencing remains to be determined. Diet-induced Avy silencing in the germ line would need to survive the remaining gestation, postnatal development, oocyte maturation, and subsequent gestation during which much other epigenetic modification is erased and rewritten (13).

Cropley et al. (5) add germ-line modification in the previous gestation to the range of epigenetic effects, which include various effects throughout gestation and postnatal effects such as that of maternal behavior on epigenetics (14). Other grandmaternal effects that appear to be epigenetic include diabetes in rats and humans. Transgenerational diabetes (F1 and F2 generations) can be induced by infusing pregnant rats (P1) with glucose during the last week of pregnancy (third trimester) (15). In humans, maternal (F1) and grandmaternal (P1) non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM) is associated with gestational diabetes (F2) (16). At least some of these models involve the recapitulation of epigenetic silencing in each generation (e.g., based on maternal behavior toward offspring; ref. 14) and probably do not require the tenacity of silencing evident in Avy.

Epigenetics at particular loci may have evolved to provide a range of phenotypes to suit a range of environmental conditions. We do not know what range of phenotypes to expect when epigenetic systems that evolved over millions of years respond to new environmental variables such as refined foods, drugs, and xenobiotics. Glucose (15–17) and endocrine disrupters (18) are examples of factors leading to apparent epigenetic transgenerational effects in mammals; however, the genes responsible for the effects are not known. Now Cropley et al. (5) show that methyl donors have transgenerational effects attributed to a known allele, Avy.

Cropley et al. (5) used a diet supplementing betaine, choline, folic acid, vitamin B12, methionine, and zinc (1, 9). Even without supplements, human diets span a huge range for these nutrients (8). These nutrient levels can be much lower in diets relying on refined foods.

In humans, the possibility, even the likelihood, that grandmaternal diets contributed to the incidence of obesity and diabetes in the current generation and that today's dietary habits will have effects for generations to come make the work of Cropley et al. (5) especially important. Their demonstration of a transgenerational effect of midgestational maternal methyl supplementation is a significant advance that should stimulate much needed research in this area.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: The author acknowledges U.S. patent no. 6,541,680 and U.S. patent application 10402704. However, these have no influence on the content of this commentary.

See companion article on page 17308.

References

- 1.Wolff GL, Kodell RL, Moore SR, Cooney CA. FASEB J. 1998;12:949–957. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaudet F, Rideout WM III, Meissner A, Dausman J, Leonhardt H, Jaenisch R. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:1640–1648. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.4.1640-1648.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolff GL. Genetics. 1978;88:529–539. doi: 10.1093/genetics/88.3.529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morgan HD, Sutherland HG, Martin DI, Whitelaw E. Nat Genet. 1999;23:314–318. doi: 10.1038/15490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cropley JE, Suter CM, Beckman KB, Martin DIK. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:17308–17312. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607090103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Michaud EJ, van Vugt MJ, Bultman SJ, Sweet HO, Davisson MT, Woychik RP. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1463–1472. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.12.1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolff GL, Roberts DW, Mountjoy KG. Physiol Genomics. 1999;1:151–163. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.1999.1.3.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cooney CA. In: Nutrigenomics: Concepts and Technologies. Kaput J, Rodriguez RL, editors. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2006. pp. 219–254. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cooney CA, Dave AA, Wolff GL. J Nutr. 2002;132:2393S–2400S. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.8.2393S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Waterland RA, Jirtle RL. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:5293–5300. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.15.5293-5300.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li E. Nat Rev Genet. 2002;3:662–673. doi: 10.1038/nrg887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blewitt ME, Vickaryous NK, Paldi A, Koseki H, Whitelaw E. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:e49. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morgan HD, Santos F, Green K, Dean W, Reik W. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:R47–R58. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meaney MJ, Szyf M. Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:456–463. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gauguier D, Bihoreau MT, Ktorza A, Berthault MF, Picon L. Diabetes. 1990;39:734–739. doi: 10.2337/diab.39.6.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harder T, Franke K, Kohlhoff R, Plagemann A. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2001;51:160–164. doi: 10.1159/000052916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aerts L, Van Assche FA. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2006;38:894–903. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anway MD, Skinner MK. Endocrinology. 2006;147:S43–S49. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]