Abstract

Numerous investigations have reported the efficacy of exogenous hyaluronan (HA) in modulating acute and chronic inflammation. The current study was performed to determine the in vitro effects of lower and higher molecular weight HA on lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-challenged fibroblast-like synovial cells. Normal synovial fibroblasts were cultured in triplicate to one of four groups: group 1, unchallenged; group 2, LPS-challenged (20 ng/ml); group 3, LPS-challenged following preteatment and sustained treatment with lower molecular weight HA; and group 4, LPS-challenged following pretreatment and sustained treatment with higher molecular weight HA. The response to LPS challenge and the influence of HA were compared among the four groups using cellular morphology scoring, cell number, cell viability, prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) production, IL-6 production, matrix metalloproteinase 3 (MMP3) production, and gene expression microarray analysis. As expected, our results demonstrated that LPS challenge induced a loss of characteristic fibroblast-like synovial cell culture morphology (P < 0.05), decreased the cell number (P < 0.05), increased PGE2 production 1,000-fold (P < 0.05), increased IL-6 production 15-fold (P < 0.05), increased MMP3 production threefold (P < 0.05), and generated a profile of gene expression changes typical of LPS (P < 0.005). Importantly, LPS exposure at this concentration did not alter the cell viability. Higher molecular weight HA decreased the morphologic change (P < 0.05) associated with LPS exposure. Both lower and higher molecular weight HA significantly altered a similar set of 21 probe sets (P < 0.005), which represented decreased expression of inflammatory genes (PGE2, IL-6) and catabolic genes (MMP3) and represented increased expression of anti-inflammatory and anabolic genes. The molecular weight of the HA product did not affect the cell number, the cell viability or the PGE2, IL-6, or MMP3 production. Taken together, the anti-inflammatory and anticatabolic gene expression profiles of fibroblast-like synovial cells treated with HA and subsequently challenged with LPS support the pharmacologic benefits of treatment with HA regardless of molecular weight. The higher molecular weight HA product provided a cellular protective effect not seen with the lower molecular weight HA product.

Introduction

Hyaluronan (HA), a common component of connective tissue, is a long, unbranched nonsulfated glycosaminoglycan essential for the normal function of diarthrodial joints. The high concentration (2.5–4 mg/ml) of HA in synovial fluid is maintained by lining type B fibroblasts and is composed of a polydispersed population with molecular weights that vary from 2 × 106 to 1 × 107 Da [1]. These large molecules can form extensive macromolecule networks, although the nature of these associations and their orientation is not resolved [2,3]. It is postulated that hydrophobic regions of these complexes provide sites for interactions with cell membranes and other phospholipids [4]. The identification of specific receptors to which HA binds – specifically cluster determinant 44, intercellular adhesion molecule 1, and the receptor for hyaluronan-mediated motility – on a diverse number of cells supports the pharmacologic activity of HA in addition to its rheologic properties [5,6]. HA can also readily enter cells by endocytosis and can interact with intracellular proteins [7]. Receptor–HA binding results in the stimulation of signaling cascades that moderate cellular functions, particularly cell migration, proliferation, and endocytosis [8,9]. The unique properties of HA are equally important for providing nutrients to cartilage, eliminating metabolic byproducts and deleterious substances from the joint cavity, and maintaining overall joint homeostasis by inhibiting phagocytosis, chemotaxis, scar formation, and angiogenesis [10,11].

Proinflammatory cytokines, free radicals, and proteinases found in pathologic conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis can adversely affect the type B synovial cells and lead to the synthesis of HA with abnormal molecular weight [12]. Furthermore, HA may be directly depolymerized by free radicals, intracellular hyaluronidases, and other glycosidases found in diseased synovium [13]. The decrease in molecular size, in combination with dilution from inflammatory infiltration of plasma fluid and proteins in aberrant joint conditions, reduces the rheologic properties of synovial fluid [14]. Viscosupplementation, a procedure in which abnormal synovial fluid is removed and replaced with purified high molecular weight HA, was developed to combat these anomalous processes [15].

Numerous in vitro investigations have reported the efficacy of exogenous HA in modulating acute and chronic inflammation, either by reducing cellular interactions [16], binding mitogen-enhancing factors [17,18], or suppressing the production of proinflammatory mediators such as IL-1β [19,20]. In vivo studies have focused on the anti-inflammatory effects [21-23] and analgesic effects [24] of HA. Interestingly, positive clinical outcomes can be achieved with HA of both high and very low molecular weight [1], and studies have shown that the lubricating characteristics of HA in synovial joints are not dependent on the HA molecular weight [25]. The effects of HA on intracellular processes may depend on the molecular weight of the HA molecule that is interacting with receptors and promoting stable receptor clustering but a definitive mechanism has not been identified [26].

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) induces characteristic and well-defined inflammatory processes and degradation cascades in synovial tissue in vitro [27-29] and in vivo [30,31], and induces gene expression alterations in other articular cells in vitro [32,33]. LPS also plays an important role as an adjuvant in the stimulation of autoimmune arthritis in rodents [34]. To gain a better understanding of the intracellular signaling events triggered by HA of differing molecular weights, this study used cellular morphology, prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) production, IL-6 production, matrix metalloproteinase 3 (MMP3) production, and a species-specific microarray to elucidate the global gene changes of fibroblast-like synovial cells treated with commercial intra-articular joint supplements prior to LPS challenge. Our goal was to identify the protective effects of HA against LPS and to determine whether these effects were dependent on the molecular weight of the HA administered. We hypothesized that higher molecular weight HA would improve the negative cellular changes associated with LPS challenge.

Materials and methods

Animals, tissue harvest and cell culture

The study protocol as described was granted ethics approval by The Ohio State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Three clinically normal adult horses 8–15 years of age were selected for the study based on normal physical and gait evaluations. Tarsocrural joints were deemed normal on the basis of palpation and gross observation at tissue harvest. Synovium was collected from the dorsomedial pouch of both tarsocrural joints and pooled within each animal after aseptic preparation and opening of the joint. Cells were isolated and grown in culture until >95% confluent and were subsequently stored in a standard cryopreservation solution (10% dimethylsulfoxide/90% fetal bovine serum) at -80°C as primary cultures. Fibroblast-like synovial cells for each animal were thawed, resuspended in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 29.2 mg/ml L-glutamine, 50 U penicillin/ml, and 50 U streptomycin/ml (DMEM-S), and were grown in monolayer under standard sterile conditions until >95% confluent (~24 hours) in Cellstar T75 flasks (Greiner Bio-One, Longwood, FL, USA). It was anticipated that fibroblast-like synovial cells were the dominant cell population in the cultures; no inflammatory cells were present. All flasks appeared to have similar, if not identical, cell populations and densities at this point.

Experimental design

Fibroblast-like synovial cells >95% confluent (day 0) were allocated in triplicate to one of four groups: group 1, unchallenged; group 2, LPS-challenged; group 3, LPS-challenged following pretreatment and sustained treatment with lower (5 × 105–7.5 × 105 Da) molecular weight HA (Bioniche Animal Health, Pullman, WA, USA) at 10 mg/ml; and group 4, LPS-challenged following pretreatment and sustained treatment with higher (3 × 106 Da) molecular weight HA (Pfizer Animal Health, New York, NY, USA) at 5 mg/ml.

Pretreatment with HA on day 0 was as follows: group 3 received 3 ml (equivalent to one dose) of lower molecular weight HA diluted in 12 ml DMEM-S, and group 4 received 3 ml (equivalent to one manufacturer's recommended dose) of higher molecular weight HA diluted in 12 ml DMEM-S. Groups 1 and 2 received 15 ml DMEM-S only.

On day 1, groups 2, 3 and 4 received a 2-hour challenge with 3 ml LPS from Escherichia coli 055:B5 (Sigma Chemical, St Louis, MO, USA) at a concentration of 20 ng/ml followed by three washes/dilutions with Gey's balanced salt solution and replacement of appropriate media by group assignment. On day 2 the media were collected and frozen at -80°C and the cells were isolated for RNA extraction.

Cellular morphology and cell count

Flasks were evaluated microscopically in triplicate for each horse and for each group on days 0–2. Morphology scores for the fibroblast-like synovial cells were assigned at three random locations throughout the center of the culture flasks at four specific time points: day 0, before the initial product application; day 1, prior to LPS challenge; day 1, immediately following 2-hour LPS challenge; and day 2, immediately prior to cell collection. Morphology scores were assigned based on the following scale: 0, >95% attached with healthy fibroblastic morphology; 1, 5–25% rounded and detached; 2, 26–50% rounded and detached; 3, 51–75% rounded and detached; and 4, >76% rounded and detached.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays

The concentrations of PGE2, IL-6, and MMP3 in cell culture media from each horse at day 2 were determined using commercial competitive ELISAs (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). All assays were performed according to the manufacturer's protocols. The optical density of each sample was read by the Ultra Microplate Reader EL808 (Bio-Tek Instruments, Winooski, VT, USA) and expressed as picograms per milliliter. Prior to running the experimental samples, it was confirmed that neither HA product significantly interfered with the activity of the assays. Briefly, two sets of standards were created: the first was made using standards as described by the manufacturer's protocol, and the second was made using these same standards following the addition of the appropriate HA product (at concentrations described above). The resulting optical densities were compared using a paired t-test analysis and no significant difference was detected.

Microarray analysis

Total RNA was isolated from the remaining cell pellet using the phenol–chloroform extraction technique (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) as described by the manufacturer's protocol. RNA of the highest quality from each animal and from each treatment group was used for species-specific microarray analysis. Sample concentration and purity were measured by use of UV spectra (260 nm and 280 nm) and were confirmed using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA). All protocols were conducted in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA). For processing, total RNA (5 μg) was reverse transcribed into double-stranded cDNA using RT/polymerase and the T7-(dT)24 primer. Biotinylated cRNA was synthesized by in vitro transcription and the cRNA products were fragmented prior to hybridization overnight at 45°C for 16 hours on an equine-specific gene expression microarray representing 3,098 unique genes, all of which have been annotated [35]. Microarrays were washed at low-stringent and high-stringent conditions and were stained with streptavidin–phycoerythrin in accordance with established protocol. The microarray design (accession number A-AFFY-81) and the experiment submission (accession number E-MEXP-940) are available online in EBI's ArrayExpress public repository [36].

Validation of microarray by real-time RT-PCR

Fibroblast-like synovial cells from three individual horses were grown under cell culture conditions as described above until they were >95% confluent. At this point, individual culture flasks from each horse were exposed to Gey's Balanced Salt Solution (unchallenged control), 100 ng/ml LPS, or 1,000 ng/ml LPS for 2 hours. Cells were immediately collected for RNA extraction as described above; total RNA from each horse was pooled within each of the three treatment groups. Microarray analysis proceeded as previously described. PCR primers for three genes expected to have great, modest, and minimal responses to LPS challenge based on previous work [35] (IL-1α, TNFα, and prostaglandin peroxide synthase, respectively) were designed for real-time RT-PCR using the Primer Express Software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Two-step RT-PCR using the SYBR® Green PCR Master Mix was performed according to the manufacturer's protocol and universal thermal cycling parameters (Applied Biosystems). Care was taken to ensure that DNA contamination was not present in the samples. The fold changes of each gene for each LPS-challenged group were calculated relative to the unchallenged control.

Statistical analyses

Objective and scored data were compared using two-way analysis of variance followed by pair-wise comparisons with a Bonferroni correction. Repeated-measures analysis was performed on the cell counts and the cell morphology data. Statistical significance was set at α = 0.05. Microarray data were analyzed using dChip version 1.3 [37] (Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA). Array normalization was performed using the invariant set procedure; model-based expression indices were computed using only perfect-match probes. Probe-set level data identified as array outliers by dChip were omitted and considered missing data in subsequent analyses. The model-based expression indices values were then exported to BRB ArrayTools version 3.2.3 for further analysis (National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Paired t tests compared gene expression between the unchallenged control group (group 1) and the LPS-challenged control group (group 2). A two-way analysis of variance compared gene expression among the LPS-challenged control group (group 2) and the two HA-treated groups (groups 3 and 4), blocking on the horse. For the probe sets showing differential expression among the three LPS-challenged groups (P < 0.005), pair-wise comparisons were performed and P values were adjusted by Holm's method. All tests involving gene expression data used a random variance model [38]. The statistical analyses for the microarray data as described above are included in the experiment submission available online in ArrayExpress [36].

Results

Cellular morphology, viability, and count

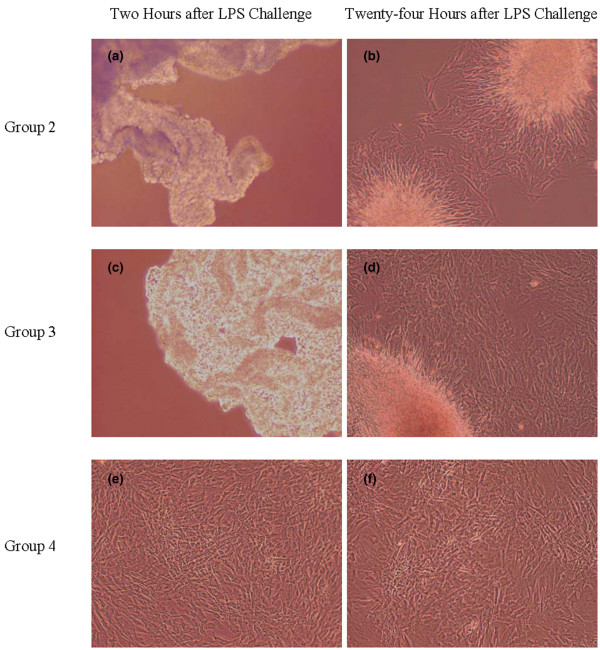

The LPS-challenged control group (group 2) and the lower molecular weight HA-treated group (group 3) had significantly greater morphology scores than the unchallenged control group (group 1) or the higher molecular weight HA-treated group (group 4) (P < 0.05; Table 1). Morphologic changes in groups 2 and 3 included reversible loss of cell attachment to the culture flask and cell contraction (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Microscopic variables for fibroblast-like synovial cells

| Day 1 (pre-lipopolysaccharide challenge) | Day 1 (post-lipopolysaccharide challenge) | Day 2 | ||||||||||

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 4 | Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 4 | Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 4 | |

| Cellular morphology (median and range) | 0 (0-0) | 0 (0-0) | 0 (0-0) | 0 (0-0) | 0 (0-0) | 3a (0–4) | 4a (3–4) | 1 (0–4) | 0 (0-0) | 3b (0–4) | 4b (3–4) | 0 (0–4) |

| Cell count (104) (mean ± SEM) | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | - | - | - | - | 118c ± 33 | 46 ± 3 | 32 ± 1 | 49 ± 7 |

| Cell viability (%) (mean ± SEM) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 97 ± 0.3 | 96 ± 1.2 | 94 ± 2.6 | 96 ± 0.1 |

Triplicate samples were performed for each of the three individual donors in the four groups. Group 1, unchallenged control; group 2, lipopolysaccharide control; group 3, pretreatment and sustained treatment with lower molecular weight hyaluronan product; group 4, pretreatment and sustained treatment with higher molecular weight hyaluronan product. 0, >95% attached; 1, 5–25% detached; 2, 26–50% detached; 3, 51–75% detached; 4, >76% detached. SEM, standard error of the mean; -, values not determined. a,b,cSignificant difference exists (P < 0.05).

Figure 1.

Representative microscopic images of fibroblast-like synovial cells post-lipopolysaccharide challenge. Representative microscopic images (400× magnification) of fibroblast-like synovial cells (a), (c), and (e) 2 hours post-lipopolysaccharide (LPS) challenge and (b), (d), and (f) 24 hours post-LPS challenge. Cells treated with the higher molecular weight hyaluronan (HA) product (group 4, pretreatment and sustained treatment with higher molecular weight HA) were protected from (d) and (e) the morphologic changes induced by LPS, including the loss of cell attachment to the culture flask and the pronounced cellular contraction that were seen in (a), (b) group 2 (LPS control) and (c), (d) group 3 (preteatment and sustained treatment with lower molecular weight HA).

Cell viability was high in all groups and no difference was found among the groups (Table 1), indicating that 20 ng/ml LPS did not kill a significant number of cells. Cell counts in the LPS-challenged groups 2, 3, and 4 were significantly lower than those of the unchallenged control group (group 1) (P < 0.05; Table 1).

Prostaglandin E2, IL-6, and MMP3 ELISAs

Expression of inflammatory products, particularly PGE2, was anticipated to increase in response to LPS challenge [39-41]. As expected, there was a greater than 1,000-fold increase in the PGE2 concentration in the cell culture media of groups 2, 3, and 4 compared with that in group 1 (P < 0.05). There was also a significant difference between the concentrations of PGE2 produced by groups 3 and 4 relative to group 2 (P < 0.05; Table 2). There was not a significant difference in PGE2 production between groups 3 and 4.

Table 2.

Mean concentrations of prostaglandin E2, IL-6, and matrix metalloproteinase 3 in culture media of fibroblast-like synovial cells determined by ELISAs

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 4 | |

| Prostaglandin E2 (pg/ml) | 15.43 ± 15.43 | 21,025a ± 6,828 | 2,998b ± 887 | 2925b ± 1,669 |

| IL-6 (pg/ml) | 1.77 ± 1.74 | 41.33c ± 16.18 | 9.49 ± 3.53 | 6.79 ± 3.11 |

| Matrix metalloproteinase 3 (pg/ml) | 2.60 ± 1.36 | 6.31d ± 0.26 | 2.96 ± 1.08 | 1.80 ± 0.90 |

Data presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean. Triplicate samples were performed for each of the three individual donors in the four groups. Group 1, unchallenged control; group 2, lipopolysaccharide control; group 3, pretreatment and sustained treatment with lower molecular weight hyaluronan product; group 4, pretreatment and sustained treatment with higher molecular weight hyaluronan product. a,bSignificant difference exists (P < 0.05). c,dSignificant difference exists (P < 0.01).

Two genes, IL-6 and MMP3, were common to the two separate gene expression analyses described below (see Gene expression profiling). Commercial competitive ELISAs were performed to confirm the trends seen with the microarray data. For both genes, protein levels in group 2 were greater than those in groups 1, 3, and 4 (P < 0.01). There was no statistical difference in protein levels among groups 1, 3, and 4 (Table 2).

Microarray validation by real-time RT-PCR

Consistent and comparable fold changes in gene expression were found between the microarray data and real-time RT-PCR for the three genes of interest (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of the fold changes between species-specific microarray analysis and real-time RT-PCR performed on fibroblast-like synovial cells exposed to lipopolysaccharide

| Fold change after 100 ng/ml lipopolysaccharide challenge | Fold change after 1,000 ng/ml lipopolysaccharide challenge | Real-time RT-PCR primer | |||

| Microarray analysis | Real-time RT-PCR | Microarray analysis | Real-time RT-PCR | ||

| IL-1α | 16 | 155 | 34 | 290 | Forward, TTGTGCCAACCAATGAGATCA |

| Reverse, TTCATGCTTTGCCTTCTTCTTG | |||||

| TNFα | 5 | 6 | 6 | 10 | Forward, GACTTGAAGTTTTCTAAGCGATGCT |

| Reverse, GGATCCACTGCCACGTACTTG | |||||

| Prostaglandin peroxide synthase | 3 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Forward, GGCCAGTTTTCCTCACCAAA |

| Reverse, AAATAAAGCTCTCTGCTTTTCATGAA | |||||

The fold changes are normalized to unchallenged fibroblast-like synovial cells.

Gene expression profiling

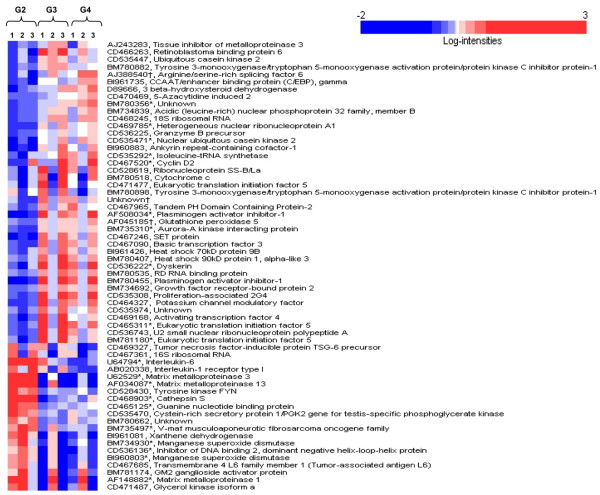

A comparison of all probe sets on the microarray between groups 1 and 2 showed that 20 ng/ml LPS significantly alerted the expression of 81 probe sets (P < 0.005; Table 4). Sixty-one probe sets were differentially expressed among the LPS-challenged groups 2, 3, and 4 (P < 0.005; Figure 2). Subsequent pair-wise comparisons of these 61 probe sets were performed between groups 2 and 3 and between groups 2 and 4; a total of 19 genes represented by 21 probe sets (11 genes and 17 genes, respectively) were differentially expressed (adjusted P < 0.005; Table 5). No significant differences in gene expression were found between groups 3 and 4 for these 61 probe sets.

Table 4.

Select/relevant genes with significant differential gene expression between the lipopolysaccharide-challenged control group and the unchallenged control group

| Genbank accession number | Equine gene | Fold change (group 2/group 1) | P value |

| AY114351 | Granulocyte chemotactic protein 2 | 10.0 | <0.0001 |

| CD528275 | Interferon-induced protein | 0.03 | <0.0001 |

| CD468799 | GRO3 oncogene | 10.0 | <0.0001 |

| BI960809 | TNFα | 2.5 | 0.0001 |

| AJ251189 | Chemoattractant protein-1 | 3.33 | 0.0016 |

| CD536631 | GRO2 oncogene | 10.0 | 0.0002 |

| BM734848 | Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan 2 | 2.0 | 0.0005 |

| AB035518 | Adrenomullin | 0.42 | 0.0006 |

| AF230359 | Urokinase plasminogen activator receptor | 1.67 | 0.0009 |

| AF053497 | Melanoma growth stimulatory activity homolog | 5.0 | 0.0014 |

| AF027335 | Prostaglandin G/H synthase-2 | 3.33 | 0.0021 |

| U62529 | Matrix metalloproteinase 3 | 2.0 | 0.0026 |

| CD467591 | Heat shock protein 70 | 2.5 | 0.0027 |

| AY056582 | Hyaluronic acid synthase 2 | 5.0 | 0.0028 |

| U64794 | IL-6 | 2.0 | 0.0037 |

Three individual donors are represented for each group. Group 1, unchallenged control; group 2, lipopolysaccharide-challenged control.

Figure 2.

Sixty-one probe sets differentially expressed (P < 0.005) among the lipopolysaccharide-challenged groups. Three individual donors are represented for each group. Group 2 (G2), LPS control; group 3 (G3), pretreatment and sustained treatment with lower molecular weight hyaluronan (HA) product; group 4 (G4), pretreatment and sustained treatment with higher molecular weight HA product. Columns represent individual animals 1, 2, and 3. Rows represent probe sets ordered by a hierarchical cluster analysis using the average linkage and 1 – Pearson correlation as the measure of dissimilarity. Shading is indicative of relative expression: white, median expression; deepening shades of red, increasing expression of the probe set above the median value; deepening shades of blue, decreasing expression of the probe set below the median value. *Gene expression differentially expressed (adjusted P < 0.005) between at least one of the pairs of treatments. †Probe set found in canines, which was included on the microarray to validate data.

Table 5.

Genes significantly upregulated or downregulated in lipopolysaccharide-challenged groups 2, 3, and 4

| Full or provisional gene annotation (accession number) | Function or activity in joint inflammationa | Fold change | Pair-wise comparisons (adjusted P values) | ||

| Group 3/group 2 | Group 4/group 2 | Group 3 vs group 2 | Group 4 vs group 2 | ||

| IL-6 (U64794) | Proinflammatory mediator [46] | 0.45 | 0.34 | 0.0015 | 0.0015 |

| Matrix metalloproteinase 13 (AF034087) | Connective tissue structure and remodeling [40] | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.0039 | 0.0005 |

| Cathepsin S (CD468903) | Proteolysis and matrix degradation [47] | 0.47 | 0.57 | 0.0022 | 0.0005 |

| Manganese superoxide dismutase (BM734930) | Antioxidant [48] | 0.62 | 0.71 | 0.0040 | 0.0040 |

| Manganese superoxide dismutase (BI960803) | 0.50 | 0.64 | 0.0117 | 0.0024 | |

| Matrix metalloproteinase 1 (AF148882) | Connective tissue structure and remodeling [40] | 0.32 | 0.35 | 0.0050 | 0.0003 |

| Matrix metalloproteinase 3 (U62529) | Connective tissue structure and remodeling [40] | 0.24 | 0.19 | 0.0035 | 0.0051 |

| Guanine nucleotide binding protein alpha inhibiting 1 (CD465125) | G-protein signaling, adenylate cyclase inhibitor [49] | 0.62 | 0.66 | 0.0079 | 0.0046 |

| V-maf oncogene (BM735497) | Unknown | 0.60 | 0.59 | 0.0035 | 0.0095 |

| Inhibitor of DNA binding 2 dominant negative helix–loop–helix protein (CD536136) | Positive regulation of cell proliferation [50] | 0.60 | 0.66 | 0.0172 | 0.0038 |

| Plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (BM780455) | Inhibitor of proteolytic activity in rheumatoid arthritis [51,52] | 2.93 | 2.59 | 0.0002 | <0.0001 |

| Plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (AF508034) | 2.11 | 2.15 | 0.0025 | <0.0001 | |

| hnRNP core protein A1 (CD469785) | Target of antinuclear autoimmunity in rheumatoid arthritis [41] | 1.41 | 1.40 | 0.0114 | 0.0028 |

| Aurora-A kinase interacting protein 1 (BM735310) | Positive regulator of proteolysis | 1.31 | 1.35 | 0.0215 | 0.0044 |

| Dyskerin (CD536222) | RNA binding, processing, and modification | 2.30 | 1.74 | 0.0046 | 0.0028 |

| Cyclin D2 (CD467520) | Induced by type I interferons after lipopolysaccharide exposure; cell cycle regulation | 1.24 | 1.50 | 0.0500 | 0.0020 |

| Isoleucine tRNA synthetase (CD535292) | Isoleucyl-rRNA aminocylation | 1.36 | 1.50 | 0.0254 | 0.0015 |

| Nuclear ubiquitous casein kinase 2 (CD535471) | Kinase in NF-κB cascade [53] | 1.62 | 1.55 | 0.0294 | 0.0048 |

| Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 5 (BM781180) | Translation initiation factor | 1.95 | 1.33 | 0.0048 | 0.0050 |

| Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 5 (CD465311) | 2.26 | 1.55 | 0.0146 | 0.0013 | |

| Unknown (BM780356) | Unknown | 1.28 | 1.55 | 0.0316 | 0.0011 |

Three individual donors are represented for each group. aBased on the Gene Ontology Database description and the literature (see references). Statistically significant P values are in bold. Group 2, lipopolysaccharide control; group 3, pretreatment and sustained treatment with lower molecular weight hyaluronan product; group 4, pretreatment and sustained treatment with higher molecular weight hyaluronan product.

Discussion

Our study focused on elucidating the in vitro effects of HA of differing molecular weights on fibroblast-like synovial cells in the face of a LPS challenge. Notably, the higher molecular weight HA product significantly reduced the morphologic change of synovial cells in vitro following a 2-hour challenge with 20 ng/ml LPS when compared with the lower molecular weight HA product (Table 1 and Figure 1). Higher molecular weight HA may preserve normal/healthy cell morphology due to a number of factors. Our results suggested that one probable mechanism to explain this finding is related to the ability of higher molecular weight HA to maintain hysteresis, compliance, and fluid exchange by reducing or dissipating stress associated with mechanical forces [42]. This facility may have enabled the fibroblast-like synovial cells in group 4 to resist contraction from the cell culture flasks when reacting to the cellular effects induced by LPS. It is also possible that pretreatment with the higher molecular weight HA product stimulated receptor-mediated intracellular signaling events that were not potentiated to the same degree by the lower molecular weight HA product in the presence of LPS [18,43,44]. It is worthwhile to note that a larger number of genes were statistically significantly altered by the higher molecular weight HA product (17 genes) than the lower molecular weight product (11 genes), and the degree of significance of given gene expression compared with LPS control was greater (that is, lower P values) with the higher molecular weight product. This is a less probable explanation, however, as no statistical difference in gene signaling was found between groups exposed to lower or higher molecular weight HA.

Other reported potential mechanisms were less supported by our data. For example, higher molecular weight HA can be more effective than lower molecular weight HA products at binding inflammatory mediators or corresponding receptors, including LPS itself and soluble agents released from challenged cells, thereby inhibiting their activity [17,39]. In particular, HA can protect surface-active phospholipids, the major boundary lubricant in joints, from lysis by phospholipase A2 [45]. Furthermore, it could be suggested that the higher molecular weight HA product maintained a greater degree of protection from LPS by creating an inert physical barrier not adequately provided by lower molecular weight HA. Appreciably, the comparable cell counts, PGE2 concentrations, and gene expression alterations of the LPS-challenged groups 3 and 4 dispute both of these theories. These results indicated that higher molecular weight HA was involved in a dynamic interaction that neither completely prevented LPS from accessing the fibroblast-like synovial cells nor bound all available LPS. Additional experimentation is warranted to fully define the mechanism behind the apparent protective effect of higher molecular weight HA relative to lower molecular weight HA upon challenge with LPS.

The gene expression profile generated by LPS challenge in this study (Table 3) was consistent with published data [35]. Addition of LPS at a concentration of 20 ng/ml induced differential expression of several genes, particularly TNFα, chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan, prostaglandin G/H synthase-2, MMP3, HA synthase 2, and IL-6. It was anticipated that there would be a reduction in the number of genes significantly altered by this concentration of LPS relative to the gene profile previously reported for 100 ng/ml by Gu and Bertone [35].

The similarity in expression profiles between the two HA-treated groups 3 and 4 suggested that differing molecular weights, within a certain range and concentration, may not be integral for initiation of intracellular signaling. The pharmacologic benefits of pretreatment and sustained treatment with exogenous HA were supported by the difference in gene expression profiles between the LPS-challenged group 2 and the HA treatment groups 3 and 4. The majority of genes that were differentially expressed between the LPS-challenged control group and the two HA treatment groups are well-recognized gene products involved with inflammatory conditions of the joint, particularly rheumatoid arthritis (Table 4) [40,41,46-53]. Additionally, we found a decrease in production of the inflammatory mediator PGE2 in groups 3 and 4, providing further evidence of an anti-inflammatory effect of HA. Interestingly, only two genes (IL-6 and MMP3) that were significantly increased in gene expression by LPS relative to the unchallenged control were significantly decreased in expression by the addition of HA, regardless of molecular weight (Tables 3 and 4). Other inflammatory mediators that were increased in gene expression by LPS, including TNFα, were not altered in either of the two HA treatment groups. In concert, these data suggested that pretreatment with a HA product resulted in a completely different and potentially beneficial gene expression profile when compared with the control groups. It is striking that treatment with HA shifted the gene expression profiles in an anti-inflammatory and anticatabolic direction relative to the LPS-challenged control group. Our data suggest that pretreatment and sustained exposure for 48 hours to HA may repress the molecular signaling of LPS by initiating independent intracellular events.

The limitations of this in vitro study with relevance to clinical application of intra-articular HA therapy are recognized. The fibroblast-like synovial cells used in this study are the largest proportion of cells found in the synovium, but are not the only component. The presence of other tissues in the joint will influence the effect of HA on overall joint homeostasis in vivo. In addition, the fibroblast-like synovial cells in this study were raised in either an environment devoid of HA (control groups 1 and 2) or in a stable environment containing HA (groups 3 and 4). This permitted a controlled evaluation of the influence of HA but did not mimic the in vivo environment of a joint, where synovial fluid is neither free of HA nor does supplemented HA permanently remain in the articular space. Future in vivo studies would provide important information on HA as an intra-articular therapy.

Although the mechanism of action of LPS in antibody-induced arthritis remains uncertain, its role in joint inflammation and arthritis pathogenesis is well recognized [29]. As such, our study using LPS provided further in vitro evidence that pre-emptive and early viscosupplementation with HA is a viable and potentially valuable treatment option for inflammatory synovitis and rheumatoid arthritis [54-56].

Conclusion

The anti-inflammatory and anticatabolic gene expression profiles of synovial cells treated with HA and subsequently challenged with LPS supports the pharmacologic benefits of treatment with HA regardless of molecular weight. The higher molecular weight HA product provided a cellular protective effect not seen with the lower molecular weight HA product.

Abbreviations

DMEM-S = Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 29.2 mg/ml L-glutamine, 50 U penicillin/ml, and 50 U streptomycin/ml; ELISA = enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; HA = hyaluronan; IL = interleukin; LPS = lipopolysaccharide; MMP3 = matrix metalloproteinase 3; PCR = polymerase chain reaction; PGE2 = prostaglandin E2; RT = reverse transcriptase; TNFα = tumor necrosis factor alpha.

Competing interests

The authors declare that this study was funded, in part, by Pfizer Animal Health, Inc.

Authors' contributions

KSS performed the cell culture work, the ELISAs, and some RNA extractions, and drafted the manuscript. ALJ performed the majority of the RNA extractions. ASR contributed to the statistics involved in the gene expression analysis. ALB conceived of and coordinated the study, edited the manuscript, and obtained funding for the project. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr Michael Radmacher for microarray analysis, Megan Cartwright for technical assistance, Timothy Vojt for photographic support, and Dr Terri Zachos for review of the manuscript. This study was funded, in part, by Pfizer Animal Health, Inc.

Contributor Information

Kelly S Santangelo, Email: santangelo.12@osu.edu.

Amanda L Johnson, Email: johnson.2740@osu.edu.

Amy S Ruppert, Email: Amy.Ruppert@osumc.edu.

Alicia L Bertone, Email: bertone.1@osu.edu.

References

- Fraser JR, Laurent TC, Laurent UB. Hyaluronan: its nature, distribution, functions and turnover. J Intern Med. 1997;242:27–33. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1997.00170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapcik L Jr and L, Lapcik L, De Smedt S, Demeester J, Chabrecek P. Hyaluronan: preparation, structure, properties, and applications. Chem Rev. 1998;98:2663–2684. doi: 10.1021/cr941199z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JE, Cummings C, Brass A, Chen Y. Secondary and tertiary structures of hyaluronan in aqueous solution, investigated by rotary shadowing-electron microscopy and computer simulation. Hyaluronan is a very efficient network-forming polymer. Biochem J. 1991;274:699–705. doi: 10.1042/bj2740699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquali-Ronchetti I, Quaglino D, Mori G, Bacchelli B, Ghosh P. Hyaluronan-phospholipid interactions. J Struct Biol. 1997;120:1–10. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1997.3908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savani RC, Cao G, Pooler PM, Zaman A, Zhou Z, DeLisser HM. Differential involvement of the hyaluronan (HA) receptors CD44 and receptor for HA-mediated motility in endothelial cell function and angiogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:36770–36778. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102273200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Entwistle J, Hall CL, Turley EA. HA receptors: regulators of signalling to the cytoskeleton. J Cell Biochem. 1996;61:569–577. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4644(19960616)61:4<569::AID-JCB10>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tammi R, Rilla K, Pienimaki JP, MacCallum DK, Hogg M, Luukkonen M, Hascall VC, Tammi M. Hyaluronan enters keratinocytes by a novel endocytic route for catabolism. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:35111–35122. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103481200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi H, Terao T. Hyaluronic acid-specific regulation of cytokines by human uterine fibroblasts. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:C1151–C1159. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.4.C1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oertli B, Beck-Schimmer B, Fan X, Wuthrich RP. Mechanisms of hyaluronan-induced up-regulation of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 expression by murine kidney tubular epithelial cells: hyaluronan triggers cell adhesion molecule expression through a mechanism involving activation of nuclear factor-kappa B and activating protein-1. J Immunol. 1998;161:3431–3437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrester JV, Balazs EA. Inhibition of phagocytosis by high molecular weight hyaluronate. Immunology. 1980;40:435–446. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olutoye OO, Barone EJ, Yager DR, Uchida T, Cohen IK, Diegelmann RF. Hyaluronic acid inhibits fetal platelet function: implications in scarless healing. J Pediatr Surg. 1997;32:1037–1040. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3468(97)90394-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl LB, Dahl IM, Engstrom-Laurent A, Granath K. Concentration and molecular weight of sodium hyaluronate in synovial fluid from patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other arthropathies. Ann Rheum Dis. 1985;44:817–822. doi: 10.1136/ard.44.12.817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald RA. Oxygen radicals, inflammation, and arthritis: pathophysiological considerations and implications for treatment. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1991;20:219–240. doi: 10.1016/0049-0172(91)90018-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bothner H, Wik O. Rheology of hyaluronate. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 1987;442:25–30. doi: 10.3109/00016488709102834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balazs EA, Denlinger JL. Viscosupplementation: a new concept in the treatment of osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol Suppl. 1993;39:3–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrester JV, Wilkinson PC. Inhibition of leukocyte locomotion by hyaluronic acid. J Cell Sci. 1981;48:315–331. doi: 10.1242/jcs.48.1.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presti D, Scott JE. Hyaluronan-mediated protective effect against cell damage caused by enzymatically produced hydroxyl (OH.) radicals is dependent on hyaluronan molecular mass. Cell Biochem Funct. 1994;12:281–288. doi: 10.1002/cbf.290120409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobetto K, Nakai K, Akatsuka M, Yasui T, Ando T, Hirano S. Inhibitory effects of hyaluronan on neutrophil-mediated cartilage degradation. Connect Tissue Res. 1993;29:181–190. doi: 10.3109/03008209309016825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawrat P, Surazynski A, Karna E, Palka JA. The effect of hyaluronic acid on interleukin-1-induced deregulation of collagen metabolism in cultured human skin fibroblasts. Pharmacol Res. 2005;51:473–477. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki A, Sasaki K, Konttinen YT, Santavirta S, Takahara M, Takei H, Ogino T, Takagi M. Hyaluronate inhibits the interleukin-1β-induced expression of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-1 and MMP-3 in human synovial cells. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2004;204:99–107. doi: 10.1620/tjem.204.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ialenti A, Di Rosa M. Hyaluronic acid modulates acute and chronic inflammation. Agents Actions. 1994;43:44–47. doi: 10.1007/BF02005763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wobig M, Bach G, Beks P, Dickhut A, Runzheimer J, Schwieger G, Vetter G, Balazs E. The role of elastoviscosity in the efficacy of viscosupplementation for osteoarthritis of the knee: a comparison of hylan G-F 20 and a lower-molecular-weight hyaluronan. Clin Ther. 1999;21:1549–1562. doi: 10.1016/S0149-2918(00)80010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth A, Mollenhauer J, Wagner A, Fuhrmann R, Straub A, Venbrocks RA, Petrow P, Brauer R, Schubert H, Ozegowski J, et al. Intra-articular injections of high-molecular-weight hyaluronic acid have biphasic effects on joint inflammation and destruction in rat antigen-induced arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7:R677–R686. doi: 10.1186/ar1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotoh S, Onaya J, Abe M, Miyazaki K, Hamai A, Horie K, Tokuyasu K. Effects of the molecular weight of hyaluronic acid and its action mechanisms on experimental joint pain in rats. Ann Rheum Dis. 1993;52:817–822. doi: 10.1136/ard.52.11.817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mabuchi K, Obara T, Ikegami K, Yamaguchi T, Kanayama T. Molecular weight independence of the effect of additive hyaluronic acid on the lubricating characteristics in synovial joints with experimental deterioration. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 1999;14:352–356. doi: 10.1016/S0268-0033(98)00084-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohkawara Y, Tamura G, Iwasaki T, Tanaka A, Kikuchi T, Shirato K. Activation and transforming growth factor-beta production in eosinophils by hyaluronan. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2000;23:444–451. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.23.4.3875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moses VS, Hardy J, Bertone AL, Weisbrode SE. Effects of anti-inflammatory drugs on lipopolysaccharide-challenged and -unchallenged equine synovial explants. Am J Vet Res. 2001;62:54–60. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.2001.62.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frean SP, Lees P. Effects of polysulfated glycosaminoglycan and hyaluronan on prostaglandin E2 production by cultured equine synoviocytes. Am J Vet Res. 2000;61:499–505. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.2000.61.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee EK, Kang SM, Paik DJ, Kim JM, Youn J. Essential roles of Toll-like receptor-4 signaling in arthritis induced by type II collagen antibody and LPS. Int Immunol. 2005;17:325–333. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer JL, Bertone AL, Malemud CJ, Mansour J. Biochemical and biomechanical alterations in equine articular cartilage following an experimentally-induced synovitis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 1996;4:127–137. doi: 10.1016/S1063-4584(05)80321-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer JL, Bertone AL. Experimentally-induced synovitis as a model for acute synovitis in the horse. Equine Vet J. 1994;26:492–495. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-3306.1994.tb04056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byron CR, Orth MW, Venta PJ, Lloyd JW, Caron JP. Influence of glucosamine on matrix metalloproteinase expression and activity in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated equine chondrocytes. Am J Vet Res. 2003;64:666–671. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.2003.64.666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathy-Hartert M, Martin G, Devel P, Deby-Dupont G, Pujol JP, Reginster JY, Henrotin Y. Reactive oxygen species downregulate the expression of pro-inflammatory genes by human chondrocytes. Inflamm Res. 2003;52:111–118. doi: 10.1007/s000110300023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshino S, Sasatomi E, Ohsawa M. Bacterial lipopolysaccharide acts as an adjuvant to induce autoimmune arthritis in mice. Immunology. 2000;99:607–614. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2000.00015.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu W, Bertone AL. Generation and performance of an equine-specific large-scale gene expression microarray. Am J Vet Res. 2004;65:1664–1673. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.2004.65.1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EBI's ArrayExpress http://www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress/

- Zhong S, Li C, Wong WH. ChipInfo: software for extracting gene annotation and gene ontology information for microarray analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3483–3486. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright GW, Simon RM. A random variance model for detection of differential gene expression in small microarray experiments. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:2448–2455. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann A, Schinzel R, Palm D, Riederer P, Munch G. High molecular weight hyaluronic acid inhibits advanced glycation endproduct-induced NF-kappaB activation and cytokine expression. FEBS Lett. 1999;453:283–287. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(99)00731-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrage PS, Mix KS, Brinckerhoff CE. Matrix metalloproteinases: role in arthritis. Front Biosci. 2006;11:529–543. doi: 10.2741/1817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astaldi Ricotti GC, Bestagno M, Cerino A, Negri C, Caporali R, Cobianchi F, Longhi M, Maurizio Montecucco C. Antibodies to hnRNP core protein A1 in connective tissue diseases. J Cell Biochem. 1989;40:43–47. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240400105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy J, Bertone AL, Muir WW. Pressure–volume relationships in equine midcarpal joint. J Appl Physiol. 1995;78:1977–1984. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1995.78.5.1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasui T, Akatsuka M, Tobetto K, Hayaishi M, Ando T. The effect of hyaluronan on interleukin-1 alpha-induced prostaglandin E2 production in human osteoarthritic synovial cells. Agents Actions. 1992;37:155–156. doi: 10.1007/BF01987905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akmal M, Singh A, Anand A, Kesani A, Aslam N, Goodship A, Bentley G. The effects of hyaluronic acid on articular chondrocytes. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87:1143–1149. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.87B8.15083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitzan DW, Nitzan U, Dan P, Yedgar S. The role of hyaluronic acid in protecting surface-active phospholipids from lysis by exogenous phospholipase A(2) Rheumatology (Oxford) 2001;40:336–340. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/40.3.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones SA, Richards PJ, Scheller J, Rose-John S. IL-6 transsignaling: the in vivo consequences. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2005;25:241–253. doi: 10.1089/jir.2005.25.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou WS, Li W, Keyszer G, Weber E, Levy R, Klein MJ, Gravallese EM, Goldring SR, Bromme D. Comparison of cathepsins K and S expression within the rheumatoid and osteoarthritic synovium. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:663–674. doi: 10.1002/art.10114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai L, Claxson A, Marklund SL, Feakins R, Yousaf N, Chernajovsky Y, Winyard PG. Amelioration of antigen-induced arthritis in rats by transfer of extracellular superoxide dismutase and catalase genes. Gene Ther. 2003;10:550–558. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez G, Sitkovsky MV. Targeting G protein-coupled A2a adenosine receptors to engineer inflammation in vivo. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2003;35:410–414. doi: 10.1016/S1357-2725(02)00177-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai D, Yamaguchi A, Tsuchiya N, Yamamoto K, Tokunaga K. Expression of ID family genes in the synovia from patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;284:436–442. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judex MO, Mueller BM. Plasminogen activation/plasmin in rheumatoid arthritis: matrix degradation and more. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:645–647. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62285-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Ny A, Leonardsson G, Nandakumar KS, Holmdahl R, Ny T. The plasminogen activator/plasmin system is essential for development of the joint inflammatory phase of collagen type II-induced arthritis. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:783–792. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62299-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimoyama Y, Sakamoto R, Akaboshi T, Tanaka M, Ohtsuki K. Characterization of secretory type IIA phospholipase A2 (sPLA2-IIA) as a glycyrrhizin GL-binding protein and the GL-induced inhibition of the CK-II-mediated stimulation of sPLA2-IIA activity in vitro. Biol Pharm Bull. 2001;24:1004–1008. doi: 10.1248/bpb.24.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto M, Hanyu T, Yoshio T, Matsuno H, Shimizu M, Murata N, Shiozawa S, Matsubara T, Yamana S, Matsuda T. Intra-articular injection of hyaluronate (SI-6601D) improves joint pain and synovial fluid prostaglandin E2 levels in rheumatoid arthritis: a multicenter clinical trial. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2001;19:377–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonaka T, Kikuchi H, Ikeda T, Okamoto Y, Hamanishi C, Tanaka S. Hyaluronic acid inhibits the expression of u-PA, PAI-1, and u-PAR in human synovial fibroblasts of osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2000;27:997–1004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuno H, Yudoh K, Kondo M, Goto M, Kimura T. Biochemical effect of intra-articular injections of high molecular weight hyaluronate in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Inflamm Res. 1999;48:154–159. doi: 10.1007/s000110050439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]