Abstract

Background

Laterally spreading tumours (LSTs) in the colorectum are usually removed by endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) even when large in size. LSTs with deeper submucosal (sm) invasion, however, should not be treated by EMR because of the higher risk of lymph node metastasis.

Aims

To determine which endoscopic criteria, including high magnification pit pattern analysis, are associated with sm invasion in LSTs and clarify indications for EMR.

Methods

Eight endoscopic criteria from 511 colorectal LSTs (granular type (LST‐G type); non‐granular type (LST‐NG type)) were evaluated retrospectively for association with sm invasion, and compared with histopathological findings.

Results

LST‐NG type had a significantly higher frequency of sm invasion than LST‐G type (14% v 7%; p<0.01). Presence of a large nodule in LST‐G type was associated with higher sm invasion while pit pattern (invasive pattern), sclerous wall change, and larger tumour size were significantly associated with higher sm invasion in LST‐NG type. In 19 LST‐G type with sm invasion, sm penetration determined histopathologically occurred under the largest nodules (84%; 16/19) and depressed areas (16%; 3/19). Deepest sm penetration in 32 LST‐NG type was either under depressed areas (72%; 23/32) or lymph follicular or multifocal sm invasion (28%; 1/32 and 8/32, respectively).

Conclusions

When considering the most suitable therapeutic strategy for LST‐G type, we recommend endoscopic piecemeal resection with the area including the large nodule resected first. In contrast, LST‐NG type should be removed en bloc because of the higher potential for malignancy and greater difficulty in diagnosing sm depth and extent of invasion compared with LST‐G type.

Keywords: laterally spreading tumour, endoscopic mucosal resection, endoscopic submucosal dissection, en bloc resection, magnification colonoscopy

The incidence of superficial colorectal tumours has been increasing recently. Among them, laterally spreading tumours (LSTs) typically extend laterally and circumferentially rather than vertically along the colonic wall1 and the frequency of invasive carcinoma is lower than for polypoid lesions of similar size. LSTs are usually removed therefore by endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) but larger such tumours may require piecemeal resection.2,3,4,5,6 LSTs with deeper submucosal (sm) invasion, however, should not be treated by EMR due to the higher risk of lymph node metastasis. As a result, it is clinically important to accurately diagnose sm invasion before treatment.

We have previously reported that granular type LSTs (LST‐G type) with large nodules or depressions tend to invade the sm.2 Recently, pit pattern analysis using magnification colonoscopy has also been reported to be useful in the diagnosis of invasive depth in early colorectal cancers.7,8,9,10,11 In addition, Kudo reported that there is another LST subtype with no granular pattern on the surface, referred to as non‐granular type (LST‐NG type),1 and clinicopathological differences between LST‐G type and LST‐NG type have been reported.3,5,12,13

The aim of this study was to analyse endoscopic criteria including pit pattern analysis conducted using high magnification endoscopy from a large number of colorectal LSTs to determine the indications for EMR.

Materials and methods

A total of 511 colorectal LSTs in 475 patients were resected endoscopically or surgically at the National Cancer Centre Hospital in Tokyo between January 1999 and December 2003.

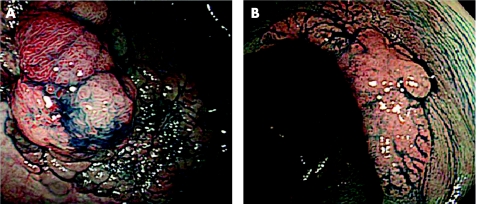

In this study, LSTs were defined as lesions ⩾10 mm in diameter with a low vertical axis extending laterally along the interior luminal wall. These lesions then were subdivided into two subtypes based on endoscopic macroscopic findings: LST‐G type with even or uneven nodules on the surface and LST‐NG type with a smooth surface (fig 1A, B). Patients excluded from the study were those who had advanced colorectal cancer, familial adenomatous polyposis, or inflammatory bowel syndrome.

Figure 1 Laterally spreading tumour (LST) characteristics: (A) LST granular type. (B) LST non‐granular type.

When a lesion was detected by conventional endoscopic examination, surface mucous was washed away with lukewarm water containing pronase (Pronase MS; Kaken Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) and then 0.4% indigo carmine dye was sprayed over the lesion in order to enhance its surface detail.

High magnification colonoscopy (CF‐240ZI, PCF‐240ZI, and CF‐200Z; Olympus Optical Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) was also used in this study. When high magnification observation with indigo carmine dye was not enough to determine the surface structure (pit pattern analysis), staining with 0.05% crystal violet was performed.6

Eight endoscopic criteria were investigated retrospectively for their possible association with sm invasion and each finding was then divided into two groups as follows:

Tumour size: ⩾20 mm or <20 mm; size was estimated for en bloc resected specimens by histopathological examination and for piecemeal resected specimens by reviewing endoscopic photographs.

Surface redness: prominent or not prominent.

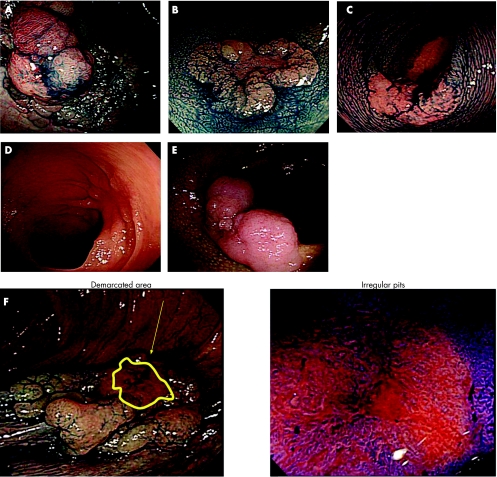

Large nodule (⩾10 mm): with or without such a nodule (fig 2A).

Demarcated depressed area: with or without such a demarcation (fig 2B).

Sclerous wall change: with or without such a change (fig 2C).

Fold convergency: with or without such a fold convergency towards the tumour (fig 2D).

Chicken skin mucosa: presence or absence of a chicken skin appearance around the tumour14,15 (fig 2E).

Pit pattern: “invasive pattern” or “non‐invasive pattern”; “invasive pattern” is characterised by irregular and distorted epithelial crests observed in a demarcated area suggesting that sm invasion is more than 1000 µm, while “non‐invasive pattern” does not have these two findings, suggesting intramucosal neoplasia or sm invasion less than 1000 µm7,8,9,16 (fig 2F).

Figure 2 Endoscopic characteristics. (A) Large nodule (⩾10 mm). (B) Demarcated depressed area. (C) Sclerous wall change. (D) Fold convergency. (E) Chicken skin mucosa. (F) Pit pattern (invasive pattern).

All endoscopic criteria were determined retrospectively by two highly experienced endoscopists (TU, YS), each of whom had previously performed over 1000 colonoscopies per year for more than five years. When there were any differences between their respective diagnoses, the two endoscopists discussed their findings and arrived at a single appropriate diagnosis.

In addition, the relationships between the various endoscopic criteria and the extent of sm invasion were analysed histopathologically in those LSTs with sm invasion.

Histopathology

Resected specimens were fixed in a 10% buffered formalin solution. Paraffin embedded samples were then sliced into 3 μm sections and stained with haematoxylin‐eosin. Histopathological diagnosis was based on the Vienna classification.17

Statistical analysis

Endoscopic criteria were subjected to univariate and multivariate analysis. Data are presented as mean (SD). Data obtained were evaluated with the χ2 and t tests using the SAS Statistical Package (SAS Institute, Tokyo, Japan). Significance level was set at 5% for each analysis. A p value <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Table 1 shows the clinicopathological characteristics of the LSTs. Although the mean size of LST‐NG type (15.9 (7.0) mm) was smaller than that of LST‐G type (23.0 (12.6) mm), the LST‐NG type had a significantly higher frequency of sm invasion (14% (32/224) v 7% (19/287), respectively; p<0.01). LST‐G type was more commonly diagnosed in the right colon and rectum (85% (245/287); 53% (153/287); and 32% (92/287), respectively). In contrast, LST‐NG type was more frequently diagnosed in the right colon (61% (136/224); p<0.001).

Table 1 Clinicopathological characteristics of laterally spreading tumours of the granular (LST‐G) and non‐granular (LST‐NG) types.

| LST‐G type | LST‐NG type | |

|---|---|---|

| No of LSTs | 287 | 224 |

| No of patients | 275 | 195 |

| Tumour size (mm) (mean (SD)) | 23.0 (12.6) | 15.9 (7.0) |

| Histological diagnosis | ||

| Adenoma or m‐Ca | 268 (93%) | 192 (86%) |

| sm‐Ca | 19 (7%) | 32 (14%) |

| Distribution | ||

| Right colon | 153 (53%) | 136 (61%) |

| Left colon | 42 (15%) | 59 (26%) |

| Rectum | 92 (32%) | 29 (13%) |

m‐Ca, intramucosal adenocarcinoma.

sm‐Ca, submucosal adenocarcinoma.

In the LST‐G type, the presence of a large nodule (⩾10 mm), demarcated depressed area, invasive pattern, prominent redness, larger tumour size (⩾20 mm), or sclerous wall change was significantly associated with an increased risk of sm invasion according to univariate analysis. Based on multivariate analysis, the only independent risk criterion for sm invasion was the existence of a large nodule (⩾10 mm) (p<0.001; odds ratio 71.01) (table 2).

Table 2 Endoscopic criteria for submucosal invasion in 287 laterally spreading tumours, granular type.

| sm‐Ca/n | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| p Value | Odds ratio | p Value | ||

| Large nodule | ||||

| ⩾10 mm | 14/47 | <0.001 | 71.01 | <0.001 |

| <10 mm | 5/240 | |||

| Redness | ||||

| Present | 6/17 | <0.001 | 1.04 | NS |

| Absent | 13/270 | |||

| Depressed area | ||||

| Present | 6/6 | <0.001 | 28.66 | NS |

| Absent | 13/281 | |||

| Pit pattern | ||||

| Present | 7/7 | <0.001 | >100 | NS |

| Absent | 12/280 | |||

| Tumour size | ||||

| ⩾20 mm | 16/173 | 0.030 | 0.95 | NS |

| <20 mm | 3/114 | |||

| Sclerous wall change | ||||

| Present | 2/2 | 0.004 | 2.48 | NS |

| Absent | 17/285 | |||

| Fold convergency | ||||

| Present | 1/1 | 0.066 | – | – |

| Absent | 18/286 | |||

| Chicken skin mucosa | ||||

| Present | 1/6 | 0.340 | – | – |

| Absent | 18/281 | |||

sm‐Ca, submucosal adenocarcinoma.

In comparison, the presence in LST‐NG type of a sclerous wall change, invasive pattern, larger tumour size (⩾20 mm), large nodule (⩾10 mm), demarcated depressed area, prominent redness, or fold convergency was significantly associated with an increased risk of sm invasion according to univariate analysis. Based on multivariate analysis, independent risk criteria for sm invasion were the existence of a sclerous wall change, invasive pattern, or larger tumour size (⩾20 mm) (p = 0.009, 0.020, and 0.001, respectively; odds ratios 34.90, 16.46, and 8.98, respectively) (table 3).

Table 3 Endoscopic criteria for submucosal invasion in 224 laterally spreading tumours, non‐granular type.

| sm‐Ca./n | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| p Value | Odds ratio | p Value | ||

| Sclerous wall change | ||||

| Present | 13/14 | <0.001 | 34.90 | 0.009 |

| Absent | 19/210 | |||

| Pit pattern | ||||

| Present | 17/19 | <0.001 | 16.46 | 0.020 |

| Absent | 15/205 | |||

| Tumour size | ||||

| ⩾20 mm | 23/67 | <0.001 | 8.98 | 0.001 |

| <20 mm | 9/157 | |||

| Depressed area | ||||

| Present | 9/12 | <0.001 | 9.70 | NS |

| Absent | 23/212 | |||

| Redness | ||||

| Present | 8/8 | <0.001 | >100 | NS |

| Absent | 24/216 | |||

| Large nodule | ||||

| ⩾10 mm | 2/2 | 0.020 | >100 | NS |

| <10 mm | 30/222 | |||

| Fold convergency | ||||

| Present | 3/7 | 0.062 | – | – |

| Absent | 29/217 | |||

| Chicken skin mucosa | ||||

| Present | 7/28 | 0.087 | – | – |

| Absent | 25/196 | |||

sm‐Ca, submucosal adenocarcinoma.

For LSTs with sm invasion, the presence of a large nodule (⩾10 mm) in LST‐G type had a higher accuracy and specificity than any other endoscopic criteria (table 4). A large nodule (⩾10 mm) had a higher accuracy of sm invasion in LST‐G type than sclerous wall change, invasive pattern, larger size, or any combination of these three risk criteria in LST‐NG type (p<0.01; 87% v 77%).

Table 4 Accuracy rates of endoscopic criteria for submucosal invasion according to macroscopic type.

| Accuracy | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large nodule (LST‐G type) | 87% (249/287) | 74% (14/19) | 88% (235/268) | 30% (14/47) |

| Pit pattern or tumour size or sclerous wall change (LST‐NG type) | 77% (174/224) | 88% (28/32) | 76% (146/192) | 38% (28/74) |

LST‐G type, laterally spreading tumour granular type; LST‐NG type, laterally spreading tumour non‐granular type; PPV, positive predictive value.

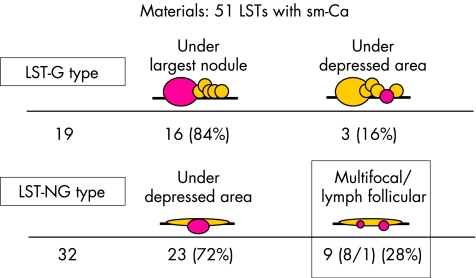

In determining the extent of penetration histopathologically in the 19 LST‐G type with sm invasion, the deepest penetration occurred under the largest nodule 84% of the time (16/19) and under the depressed area in the other three (16%; 3/19). In contrast, the deepest penetration in the 32 LST‐NG type with sm invasion occurred under the depressed area (72%; 23/32) or consisted of lymph follicular or multifocal sm invasion (28%; 9/32; 1/32, and 8/32, respectively) (fig 3).

Figure 3 Histopathological analysis of submucosal penetration. LST‐G type, laterally spreading tumour granular type; LST‐NG type, laterally spreading tumour non‐granular type; sm‐Ca, submucosal adenocarcinoma.

Discussion

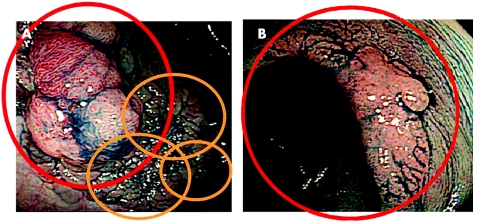

In this large study, we established that LST‐NG type has a higher potential for malignancy than LST‐G type. Based on this result and previous reports that LST‐G type and LST‐NG type differ in their genetic alterations,12,13 we suggest that different therapeutic strategies are required for treating LSTs according to their specific macroscopic type (fig 4).

Figure 4 Endoscopic mucosal resection therapeutic strategies. (A) For colorectal laterally spreading tumour granular type. (B) For colorectal laterally spreading tumour non‐granular type.

Pit pattern analysis using high magnification colonoscopy has been reported to be useful in the differential diagnosis of intramucosal and sm invasive cancers7,8,9,10,11 and in differentiating non‐neoplastic and neoplastic lesions.18,19,20 Analysis of pit patterns also played an important part in this study.

Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) was not used to determine the depth of cancer invasion in this study because we previously reported that high magnification colonoscopy is superior to EUS for determination of invasion depth in early colorectal cancers.16

We investigated endoscopic criteria, including high magnification diagnoses of pit patterns, in order to predict sm invasion before treatment in a large number of two subtypes of LSTs, LST‐G type and LST‐G type, and found that there were differences in the endoscopic criteria for predicting sm invasion between these two LST subtypes. Multivariate analysis showed that an endoscopic criterion of a large nodule (⩾10 mm) in LST‐G type and the existence of a sclerous wall change, invasive pattern, or a larger tumour size (⩾20 mm) in LST‐NG type were independent risk criteria for sm invasion.

In this study, pit pattern high magnification diagnosis proved to be useful for predicting sm invasion in LSTs, particularly LST‐NG type, although it was not as helpful with LST‐G type. The existence of a large nodule in LST‐G type was the most reliable risk criterion for determining sm invasion. Lack of pit pattern abnormalities in LST‐G type patients may be due to the fact that some LST‐G type with large nodules invade deeply into the sm layer without destructive surface changes compared with LST‐NG type lesions.21

In considering therapeutic strategies, EMR should be the firstline treatment for most LSTs because of lower invasive carcinoma frequency compared with polypoid lesions of similar size. Lymph node metastasis is more frequently present in deeper sm invasive cancer.22,23,24 As a result, we should avoid EMR for deeper sm invasive cancer because histological assessment is difficult, incomplete EMR is thought to cause accelerated growth of any residual cancer, and is also considered to be a positive risk factor for distant metastasis.25,26 Recognising the importance of the reported endoscopic criteria for predicting sm invasion therefore is essential for determining the correct treatment choice in any given case.

The presence of deeper sm invasion in LST‐G type was relatively low (6.6%; 19/287) with the vast majority (84%) of carcinoma invasions of the sm layer in LST‐G type occurring under the largest nodule,2 as revealed by histopathological examinations. Based on this, we recommend that the area including a large nodule in LST‐G type should be resected first endoscopically followed by the remaining tumour (fig 4A).

In contrast, nearly 30% of LST‐NG type revealed lymph follicular or multifocal sm invasion, both of which were difficult to diagnose by the indicated endoscopic criteria prior to treatment. Such tumours therefore should be removed en bloc to ensure an accurate histopathological diagnosis (fig 4B). As LST‐NG type ⩾20 mm are technically more difficult to remove en bloc by conventional EMR techniques2,3,27 and LST‐NG type have a higher malignancy potential than LST‐G type, we believe that endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD)28,29,30,31 or laparoscopy assisted colectomy should be the techniques of choice for en bloc resection of LST‐NG type ⩾20 mm.

Although en bloc resection allows for accurate histological assessment, no residual tumour, and lower local recurrence, colorectal ESD is not widespread, even among Japanese colonoscopists because of its technical difficulty, longer procedure time, and increased risk of perforation compared with conventional EMR. Sano et al reported that the incidence of perforation in ESDs using an insulation tipped electrosurgical knife (IT knife) was considerably higher, occurring in 14.3% (2/14) of such cases.30

In order to reduce these negative factors, further refinements in devices such as the IT knife, improved submucosal injection solutions,29 and better traction systems29,31 will be necessary. While still in the developmental stages at the present time, it may be possible for colorectal ESD to become the standard procedure for all LSTs, regardless of their macroscopic type, as improvements facilitating easier, faster, and safer procedures are made in the future.

Conclusion

LST‐G type and LST‐NG type lesions differ both in terms of their frequency of sm invasion and their respective endoscopic criteria for predicting such sm invasion. In determining the appropriate therapeutic strategy therefore it is necessary to consider the most suitable treatment based on the specific macroscopic type of LST.

Abbreviations

LST - laterally spreading tumour

LST‐G type - LST granular type

LST‐NG type - LST‐non granular type

sm - submucosal

EMR - endoscopic mucosal resection

ESD - endoscopic submucosal dissection

EUS - endoscopic ultrasonography

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Kudo S. Endoscopic mucosal resection of flat and depressed types of early colorectal cancer. Endoscopy 199325455–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saito Y, Fujii T, Kondo H.et al Endoscopic treatment for laterally spreading tumors in the colon. Endoscopy 200133682–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tanaka S, Haruma K, Oka S.et al Clinicopathologic features and endoscopic treatment of superficially spreading colorectal neoplasms larger than 20 mm. Gastrointest Endosc 20015462–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tamura S, Nakajo K, Yokoyama Y.et al Evaluation of endoscopic mucosal resection for laterally spreading rectal tumors. Endoscopy 200436306–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hurlstone D P, Sanders D S, Cross S S.et al Colonoscopic resection of lateral spreading tumours: a prospective analysis of endoscopic mucosal resection. Gut 2004531334–1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kiesslich R, Neurath M F. Endoscopic mucosal resection: an evolving therapeutic strategy for non‐polypoid colorectal neoplasia. Gut 2004531222–1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fujii T, Hasegawa R T, Saitoh Y.et al Chromoscopy during colonoscopy. Endoscopy 2001331036–1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsuda T, Fujii T, Ono A.et al Effectiveness of magnifying colonoscopy in diagnosing the depth of invasion of colorectal neoplastic lesions: invasive pattern is an indication for surgical treatment. Gastrointest Endosc 200357AB176 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saito Y, Emura F, Matsuda T.et al Invasive pattern is an indication for surgical treatment. Gut 2004. http://gut.bmjjournals.com/cgi/eletters/53/2/284

- 10.Kudo S, Tamura S, Nakajima T.et al Diagnosis of colorectal tumorous lesions by magnifying endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 1996448–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kato S, Fujii T, Koba I.et al Assessment of colorectal lesions using magnifying colonoscopy and mucosal dye spraying: can significant lesions be distinguished? Endoscopy 200133306–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fujii T, Oda K, Yoshida S.et al The features of clinicopathological and genetic background in laterally spreading tumor: endoscopic diagnosis of the depth of invasion. Shoukaki Naisikyo (Digestiva Endoscopia) 19979181–191. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Noro A, Sugai T, Habano W.et al Analysis of Ki‐ras and p53 gene mutations in laterally spreading tumors of the colorectum. Pathol Int 200353828–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muto T, Kamiya J, Sawada T.et al Clinicopathological study of white spots of the colonic mucosa around polyps, with special reference to the endoscopic diagnosis of invasive carcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc 198430231–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shatz B A, Weinstock L B, Thyssen E P.et al Colonic chicken skin mucosa: an endoscopic and histological abnormality adjacent to colonic neoplasms. Am J Gastroenterol 199893623–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fujii T, Kato S, Saito Y.et al Diagnostic ability of staging in early colorectal cancer—comparison with magnifying colonoscopy and endoscopic ultrasonography. Stomach Intestine 200136817–827. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schlemper R J, Riddell R H, Kato Y.et al The Vienna classification of gastrointestinal epithelial neoplasia. Gut 200047251–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Konishi K, Kaneko K, Kurahashi T.et al A comparison of magnifying and non magnifying colonoscopy for diagnosis of colorectal polyps: A prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc 20035748–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Togashi K, Konishi F, Ishizuka T.et al Efficacy of magnifying endoscopy in the differential diagnosis of neoplastic and non‐neoplastic polyps of the large bowel. Dis Colon Rectum 1999421602–1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fu K I, Sano Y, Kato S.et al Chromoendoscopy using indigo carmine dye spraying with magnifying observation is the most reliable method for differential diagnosis between non‐neoplastic and neoplastic colorectal lesions: a prospective study. Endoscopy 2004361089–1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kudo S, Kurahashi T, Kashida H.et al Diagnosis of the depth of invasion of colorectal lesions using magnifying colonoscopy. Stomach Intestine 200439747–752. [Google Scholar]

- 22. The Paris endoscopic classification of superficial neoplastic lesions: esophagus, stomach, and colon: November 30 to December 1, 2002. Gastrointest Endosc 200358(Suppl 6)S3–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tanaka S, Haruma K, Teixeira C R.et al Endoscopic treatment of submucosal invasive colorectal carcinoma with special reference to risk factors for lymph node metastasis. J Gastroenterol 199530710–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kitajima K, Fujimori T, Fujii S.et al Correlations between lymph node metastasis and depth of submucosal invasion in submucosal invasive colorectal carcinoma: a Japanese collaborative study. J Gastroenterol 200439534–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tanaka S, Haruma K, Tanimoto T.et al Ki‐67 and transforming growth factor alpha (TGF‐α) expression in colorectal recurrent tumors after endoscopic resection. Recent Adv Gastroenterol Carcinogenesis 199611079–1083. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Netzer P, Forster C, Biral R.et al Risk factor assessment of endoscopically removed malignant colorectal polyps. Gut 199843669–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Uraoka T, Fujii T, Saito Y.et al Effectiveness of glycerol as a submucosal injection for EMR. Gastrointest Endosc 200561736–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soetikno R M, Gotoda T, Nakanishi Y.et al Endoscopic mucosal resection. Gastrointest Endosc 200357567–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yamamoto H. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of early cancers and large flat adenomas. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 20053(Suppl 1)S74–S76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sano Y, Machida H, Fu K I.et al Endoscopic mucosal resection and submucosal dissection method for large colorectal tumors. Dig Endosc 200416(Suppl)S88–S91. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saito Y, Emura F, Matsuda T.et al A new sinker‐assisted endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal tumors. Gastrointest Endosc 200562297–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]