Abstract

Aims

To determine if central corneal thickness (CCT) changes over time and if this change relates to glaucoma progression.

Methods

39 patients (64 eyes) with open angle glaucoma, ocular hypertension, glaucoma suspect status, or a normal eye examination were examined at two visits. CCT, age, race, sex, family history of glaucoma, presence of diabetes and systemic hypertension, diagnosis, visual acuity, spherical equivalent, intraocular pressure, vertical and horizontal cup to disc ratios, number of glaucoma medications prescribed, Advanced Glaucoma Intervention Study (AGIS) score and mean deviation of Humphrey visual fields, and interventions required were recorded. Statistical analysis used the Wilcoxon signed ranks test, linear regression, and analysis of variance.

Results

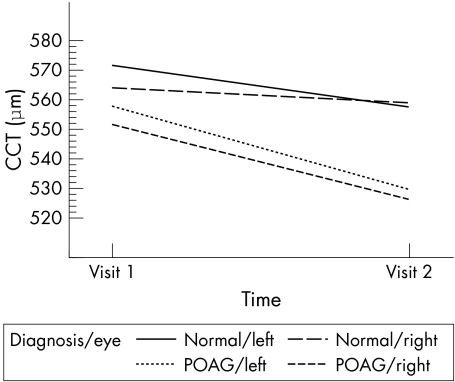

Between the two visits (mean 8.2 years apart), mean CCT decreased by 17 μm in right eyes (p<0.002) and by 23 μm in left eyes (p<0.001). This decrease was greater in right eyes of patients with primary open angle glaucoma than in normals (p = 0.041). There was no significant association between change in CCT and other examination parameters. Change in CCT was not associated with topical carbonic anhydrase inhibitor use.

Conclusion

In this longitudinal study, CCT decreased over time, but this may not be related to glaucoma progression.

Keywords: corneal thickness, pachymetry, open angle glaucoma

Central corneal thickness (CCT) has recently been shown to be an important risk factor for the development and severity of glaucoma.1,2 The clinical use of CCT measurements has become so important that it directly affects glaucoma management strategy in 15% of patients.3 Corneal thickness decreases throughout infancy and reaches adult thickness between the ages of 2–4 years.4,5 Several published studies suggest that CCT does not change with age after early childhood,6,7 but these have been cross sectional and not longitudinal in nature. The purpose of this longitudinal study is to determine if CCT changes over time in a selected patient cohort, and if this change is related to the rate of glaucomatous progression.

Materials and methods

Institutional review board/ethics committee approval was obtained. All patients were evaluated at the Duke University Eye Center, Durham, NC, USA. A previously identified cohort of 109 patients who underwent ophthalmological examination by Herndon et al in a published study from 19978 was contacted for inclusion in this study. All available patients from this cohort underwent repeat ophthalmological examination, and results were compared to the first visit performed for the previously published study. Inclusion criteria were previous inclusion in the 1997 study, and a diagnosis of open angle glaucoma, ocular hypertension, glaucoma suspect, or normal. Exclusion criteria were history of corneal or retinal surgery, laser treatment, or pathology; or recent contact lens wear. At the first visit, date of birth, sex, race, and family history of glaucoma in a first degree relative were recorded per patient. At both the first and second visits, the following were recorded per patient: examination date, ocular diagnosis, and presence of diabetes mellitus and systemic hypertension as reported by the patient. At both the first and second visits, the following were recorded per eye: Snellen visual acuity, spherical equivalent, intraocular pressure by Goldmann applanation, average CCT, visual field data where available, vertical and horizontal cup disc ratios, number of glaucoma medications prescribed, and number of topical and systemic carbonic anhydrase inhibitors prescribed. At the second visit, any surgical glaucoma intervention required between the two visits was recorded per eye.

Goldmann applanation was measured before dilation; when two or more predilation measurements were charted, the average of those pressures was recorded. CCT at both visits was performed by ultrasonic pachymetry (Storz Compuscan Ultrasonic Pachymeter System; Storz, St Louis, MO, USA at the first visit, and DGH 550 Pachette 2; DGH Technology, Exton, PA, USA at the second visit) immediately following Goldmann applanation. The average of five CCT readings was recorded. Combination eye drops, such as timolol/dorzolamide, were counted as two glaucoma medications; oral pressure lowering medications, such as acetazolamide, were counted as one glaucoma medication.

Visual field data included type of visual field analysis performed, Advanced Glaucoma Intervention Study (AGIS) score, mean deviation of visual field, fixation losses, false negative responses, and false positive responses. Right and left eyes were analysed separately. The AGIS score has been described in detail previously.9 In brief, the visual fields are graded on a scale of 0–20 based on the degree of damage on the total deviation printout. A score of 0 represents a normal visual field; 1–5 represents mild disease; 6–11, moderate disease; 12–17, severe disease; and 18–20, end stage glaucoma. Patients with any included diagnosis other than normal underwent visual field testing by Humphrey automated 24‐2 (Humphrey Systems, Dublin, CA, USA) or 30‐2 full threshold or Swedish Interactive Thresholding Algorithm (SITA) Standard perimetry protocols if their visual function allowed, or by Humphrey automated 10‐2 SITA standard perimetry if their glaucomatous damage was deemed very severe. Patients underwent Goldmann manual perimetry if there were not able to complete Humphrey automated visual field testing. Normal patients or patients whose visual acuity was too poor for automated or manual visual field testing in that eye did not have data for that eye entered into the visual field categories. Only patients who had reliable Humphrey automated 24‐2 or 30‐2 SITA standard or full threshold perimetry within 3 months of each visit had their visual field data included in the statistical analysis. Reliable Humphrey automated perimetry was defined by having fewer than two of the following characteristics: fixation losses greater than 20%, false positive responses greater than 33%, or false negative responses greater than 33%. This reliability criterion was adapted from the AGIS reliability ratings.9 Each Humphrey 24‐2 or 30‐2 visual field was scored by one masked grader (JSW) according to the AGIS scoring system.9 In the case of 30‐2 Humphrey visual fields, the outermost circumference of testing points was not included in the scoring so that the remaining testing points fit the AGIS scoring template for 24‐2 visual fields.

One masked grader (LWH) determined vertical and horizontal cup‐disc ratios for each eye. Cup‐disc ratios were judged using stereoscopic optic disc photographs from each patient's visit when available, or by evaluating detailed chart drawings from each visit when photographs were not available.

Initially, descriptive statistics (number and percentage for categorical variables and number, mean, and standard deviation for continuous variables) were obtained, separately for previous and current visits. In addition, changes in outcome measures (AGIS score, mean deviation, vertical and horizontal cup to disc ratios, and number of glaucoma medications prescribed) were computed in order to assess progression of glaucoma. The significance of changes in these variables was assessed using the paired t test or Wilcoxon signed ranks test, as the data dictated.

Subsequently, each predictor variable (length of follow up, age, sex, race, diagnosis, diabetes, hypertension, family history of glaucoma, previous and current visual acuity, spherical equivalent, intraocular pressure, CCT, as well as change in visual acuity, spherical equivalent, intraocular pressure, and CCT) was assessed individually for its relation to change in degree of damage from glaucoma (AGIS score, mean deviation, and vertical and horizontal cup‐disc ratios) and number of glaucoma medications prescribed. For categorical variables (sex, race, diagnosis, diabetes, hypertension, family history of glaucoma), analysis of variance or the Kruskall‐Wallis test was used to assess whether differences in the changes in outcome variables exist among categories of these predictor variables. The relation between initial and current values and in changes in continuous predictor variables (age, visual acuity, spherical equivalent, intraocular pressure, and CCT) and the changes in outcome variables were assessed using correlation and linear regression. Finally, all individually significant predictor variables were combined in a single regression model to assess their joint effects on the outcome variables.

Results

Descriptive statistics for demographic variables are listed in table 1. Of the 109 patients (184 eyes) originally included in the 1997 study,8 64 eyes of 39 patients were included in the present study. Mean length of time between the two examinations was 8.2 years (range 4.7–8.5 years). Thirty two eyes were right eyes and 32 eyes were left eyes. Patients were predominantly female (54%) and white (69%). Mean age at the second visit was 66.9 years. Twenty nine per cent of patients had a positive family history of glaucoma. At the first visit, 15% had diabetes mellitus and 15% had systemic hypertension. At the second visit, 18% had diabetes mellitus and 44% had systemic hypertension.

Table 1 Descriptive statistics for demographic variables.

| Age at second visit | |

| Number | 39 |

| Mean (SD) | 66.9 (12.8) |

| Median | 67.8 |

| Minimum, maximum | 41, 87 |

| Interval between visits (years) | |

| Mean (SD) | 8.1 (0.593) |

| Median | 8.2 |

| Minimum, maximum | 4.7, 8.5 |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 18 (46) |

| Female | 21 (54) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 27 (69) |

| Black | 9 (23) |

| Unknown | 3 (8) |

| Diagnosis, n (%) | |

| At first visit | |

| POAG | 17 (44) |

| NTG | 1 (3) |

| OHT | 5 (13) |

| Suspect | 1 (3) |

| Pigmentary | 3 (8) |

| Normal | 12 (31) |

| At second visit | |

| POAG | 20 (51) |

| NTG | 1 (3) |

| OHT | 1 (3) |

| Suspect | 4 (10) |

| Pigmentary | 3 (8) |

| Pseudoexfoliation | 1 (3) |

| Normal | 9 (23) |

| Positive family history, n (%) | 11 (29) |

| Diabetes N (%) | |

| At first visit | 6 (15) |

| At second visit | 7 (18) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | |

| At first visit | 6 (15) |

| At second visit | 17 (44) |

POAG, primary open angle glaucoma; NTG, normal tension glaucoma; OHT, ocular hypertension; Suspect, glaucoma suspect; Pigmentary, pigmentary glaucoma; Pseudoexfoliation, pseudoexfoliation glaucoma.

Descriptive statistics for ophthalmic variables are listed in table 2. Sixteen right eyes and 15 left eyes underwent reliable SITA or full threshold Humphrey visual field testing at both visits and thus had data included in visual field statistical analysis. Intraocular pressure decreased by a mean of 2.32 mm Hg (p = 0.015) for left eyes. CCT decreased by a mean of 17.1 μm (p = 0.018) for right eyes and 23.2 μm (p<0.001) for left eyes between the two visits. No other variables had statistically significant mean levels of change between the two visits.

Table 2 Descriptive statistics for ophthalmic variables.

| Variable | Right eye | Left eye | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First visit | Second visit | Change between visits | p value of change | First visit | Second visit | Change between visits | p value of change | ||

| Visual acuity in logMar units | |||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.076 (0.142) | 0.161 (0.270) | 0.086 (0.305) | 0.120 | 0.107 (0.189) | 0.193 (0.286) | 0.051 (0.231) | 0.222 | |

| Median | 0.000 | 0.097 | 0.000 | 0.097 | |||||

| Minimum, maximum | −0.125, 0.477 | −0.125, 1.000 | 0.000, 0.699 | 0.000, 1.301 | |||||

| Spherical equivalent (dioptres) | |||||||||

| Mean (SD) | −1.258 (2.46) | −1.419 (2.50) | 0.07 (1.60) | 0.805 | −1.523 (2.39) | −1.231 (2.24) | 0.23 (1.08) | 0.238 | |

| Median | −0.625 | −0.75 | −0.875 | −0.75 | |||||

| Minimum, maximum | −6.75, 1.75 | −7.25, 2.00 | −8.75, 1.75 | −8.50, 1.75 | |||||

| IOP (mm Hg) | |||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 18.1 (7.29) | 15.8 (5.17) | −2.05 (6.31) | 0.076 | 16.7 (5.00) | 14.2 (4.80) | −2.32 (5.11) | 0.015 | |

| Median | 18.0 | 14.0 | 16.0 | 14.0 | |||||

| Minimum, maximum | 8.0, 46.0 | 9.0, 30.0 | 8.0, 29.0 | 6.0, 28.0 | |||||

| CCT (μm) | |||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 567 (33.4) | 547 (49.3) | −17.1 (28.3) | 0.018 | 574 (32.2) | 550 (39.9) | −23.2 (23.4) | <0.001 | |

| Median | 560 | 553 | 568 | 548 | |||||

| Minimum, maximum | 521, 655 | 415, 643 | 525, 647 | 460,635 | |||||

| AGIS score | |||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 2.29 (2.78) | 2.06 (3.15) | 0.273 (2.76) | 0.750 | 3.74 (3.84) | 4.13 (5.22) | 2.08 (3.29) | 0.051 | |

| Median | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | |||||

| Minimum, maximum | 0, 9 | 0, 10 | 0, 10 | 0, 14 | |||||

| Mean deviation in decibels | |||||||||

| Mean (SD) | −2.81 (3.57) | −3.58 (4.86) | −1.26 (3.89) | 0.284 | −4.59 (4.60) | −5.12 (6.32) | −0.963 (4.84) | 0.505 | |

| Median | −2.55 | −2.23 | −5.42 | −3.78 | |||||

| Minimum, maximum | −10.47, 3.66 | −12.92, 1.35 | −11.99, 2.86 | −16.08, 1.07 | |||||

| Vertical cup to disc ratio | |||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.679 (0.252) | 0.655 (0.235) | 0.013 (0.141) | 0.668 | 0.684 (0.256) | 0.665 (0.259) | 0.017 (0.154) | 0.602 | |

| Median | 0.775 | 0.700 | 0.750 | 0.725 | |||||

| Minimum, maximum | 0.1, 1.0 | 0.15, 1.0 | 0.1, 1.0 | 0.1, 1.0 | |||||

| Horizontal cup to disc ratio | |||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.640 (0.247) | 0.625 (0.245) | 0.021 (0.120) | 0.403 | 0.676 (0.242) | 0.636 (0.243) | 0.000 (0.136) | 0.988 | |

| Median | 0.750 | 0.700 | 0.750 | 0.700 | |||||

| Minimum, maximum | 0.1, 0.9 | 0.15, 0.95 | 0.1, 0.95 | 0.1, 0.99 | |||||

| Number of medications | |||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 1.125 (1.040) | 0.909 (1.011) | −0.194 (1.046) | 0.311 | 1.125 (1.100) | 0.788 (1.023) | −0.406 (1.214) | 0.068 | |

| Median | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 | |||||

| Minimum, maximum | 0, 3 | 0, 3 | 0, 4 | 0, 3 | |||||

| Glaucoma surgical intervention required* | |||||||||

| ALT | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |||||

| SLT | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Trab/MMC | 6 | 1 | 5 | 1 | |||||

| Phaco/IOL/Trab/MMC | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | |||||

| LPI | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |||||

| Baerveldt | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |||||

| None | 21 | 28 | 22 | 30 |

IOP, intraocular pressure; CCT, central corneal thickness; AGIS, Advanced Glaucoma Intervention Study. *First visit = intervention performed before first visit, second visit = intervention performed between first and second visits, ALT, argon laser trabeculoplasty; SLT, selective laser trabeculoplasty; Trab/MMC, trabeculectomy with mitomycin C; Phaco/IOL/Trab/MMC, combined phacoemulsification with intraocular lens implant plus trabeculectomy with mitomycin C; LPI, laser peripheral iridotomy; Baerveldt, Baerveldt 350 tube implant.

In univariate statistical analysis, the only statistically significant relation was that visual acuity for right eyes worsened significantly between visits for black people compared to white people (p = 0.004). There were no other statistically significant relations between predictor variables and change in outcome variables nor was there any statistically significant relation between predictor variables and change in CCT, or between change in CCT between the two visits and the use of topical or oral carbonic anhydrase inhibitors at either visit.

When study patients with either POAG or a normal eye examination at the second visit were analysed, those with POAG had a mean decrease in CCT of 26 μm (p = 0.004) for right eyes and 28 μm (p<0.001) for left eyes. Patients with a normal eye examination had a mean decrease in CCT of 5 μm (p = 0.440) for right eyes and 14 μm (p = 0.031) for left eyes (fig 1). This difference between the mean decreases in CCT for POAG and normal patients was statistically significant for right eyes (p = 0.041), but not statistically significant in left eyes (p = 0.106). When only patients with POAG at the second visit (n = 16) were included in repeat univariate analysis for any change in predictor or outcome variables associated with change in CCT as the dependent variable, the only statistically significant findings were a smaller decrease in mean CCT for right eyes (p = 0.035) in black people (−8.5 μm) compared to white people (−32.5 μm), a smaller decrease in mean CCT for right eyes (p = 0.036) for those with hypertension at the second visit (−12.0 μm) compared to those without hypertension at the second visit (−32.5 μm), and a decrease in mean intraocular pressure for left eyes with increasing CCT (p = 0.052).

Figure 1 Longitudinal changes in central corneal thickness. CCT, central corneal thickness, POAG, primary open angle glaucoma.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that CCT may decrease over time, and that this change may be more marked in POAG patients than in normal patients. There was no significant change in any outcome variable with change in CCT for either POAG patients or all study patients as a group, so this decrease in CCT does not seem to be related to glaucomatous progression. Although our study population was relatively small, to our knowledge this study has the longest follow up time in the literature in measuring change in CCT.10

This CCT decrease in POAG patients especially has clinical as well as statistical significance, since a patient's glaucoma risk assessment may be directly affected by this decrease. The Early Manifest Glaucoma Trial demonstrated that glaucoma progression was lessened by 10% for every millimetre of mercury decrease in intraocular pressure, so adjusting intraocular pressure for decreased CCT as found in our study may in fact alter a glaucoma patient's risk profile for progression.11

The longitudinal decrease in mean CCT in our study is in agreement with the cross sectional finding of the Barbados Eye Studies that thinner corneas are associated with increasing age.12 In a cross sectional study of multiracial patients, Aghaian et al showed a 3 μm decrease in CCT per decade of age.13 Foster et al found a 5–6 μm decrease in CCT per decade of age in a cross sectional study of Mongolian patients,14 while the Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study revealed a 6.3 μm decrease in CCT per decade of age when analysed cross sectionally.15 The longitudinal nature of our study may be the reason why our patients had more marked corneal thinning with time. With regard to the relation between age, changing CCT, and endothelial cell density, Korey et al showed that increasing age was associated with a decrease in cell density but was not associated with a change in CCT.16 Further prospective study is needed to clarify these associations.

The reason for the decrease in mean CCT over time is not entirely clear. Black race and hypertension were significantly associated with decreasing CCT only in glaucomatous right eyes, whereas decreasing intraocular pressure was significantly associated with decreasing CCT only in glaucomatous left eyes. Further study into these associations will be needed to elucidate any possible causes for decreasing CCT.

In this study, CCT was measured by different operators. In previous studies of ultrasound pachymetry, the correlation coefficient for intraobserver variability was measured to be 0.979–0.995, whereas interobserver variability was estimated to be 0.890–0.986.17,18 Significant variations of over 15 μm have been found in ultrasound pachymetry when performed by the same operator or by different operators.18 However, this variability would affect only standard deviation of CCT measurements but not mean CCT, which decreased significantly in our study.

CCT is known to decrease progressively throughout the day, with highest values found in the morning.19,20 It is estimated that measuring CCT between 11 am and 2 pm approximates a patient's mean CCT given its diurnal fluctuation. While our study does not control for time of day when measuring CCT, our study patients had CCT measured at random times so that there would not be any consistent bias in our results.

While CCT is not affected in the long term by either phacoemulsification or trabeculectomy, the cornea may thicken in the immediate postoperative period. However, it returns to normal thickness by 1 week to 3 months later.4,21 None of our study patients had undergone intraocular surgery within 3 months before either study visit. Although the number of patients in our study who underwent any incisional surgery is small, the decrease in mean CCT supports the previous finding that even with endothelial cell loss due to surgery, CCT does not increase.4

One weakness of this study is that a different ultrasound pachymeter was used at each of the two study visits. The original pachymeter is no longer available. According to manufacturers, ultrasound pachymetry has a precision of 5–10 μm, less than the mean decrease found in our study cohort.4 Rainer et al found that mean CCT was within 6 μm when measured with three different ultrasound pachymeters.22 While it is possible that using two different ultrasound pachymeters may have affected our results, the variability between them is likely to have been smaller than the mean decrease found in CCT between visits.

Wickham et al found that CCT measured prospectively over a 3 month time interval tended to increase.10 The decrease in mean CCT in our study may be linked to the longer length of time between the two measurements. Further study will be needed to determine the reason for the change in mean CCT over time. Since the Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study has brought CCT as a risk factor to the forefront of glaucoma management,1 ophthalmologists should consider performing pachymetry more than once in a glaucoma patient's lifetime since the change in CCT over time may significantly affect that patient's therapy.

Acknowledgements

Our thanks to Cindy Skalak for her help in coordinating this study. Dr Herndon has received grant support from Allergan, Inc to help conduct this study. None of the authors has any conflict of interest related to this manuscript.

Abbreviations

AGIS - Advanced Glaucoma Intervention Study

CCT - central corneal thickness

POAG - primary open angle glaucoma

SITA - Swedish Interactive Thresholding Algorithm

References

- 1.Gordon M O, Beiser J A, Brandt J D.et al The ocular hypertension treatment study: baseline factors that predict the onset of primary open‐angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol 2002120714–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herndon L W, Weizer J S, Stinnett S S. Central corneal thickness as a risk factor for advanced glaucoma damage. Arch Ophthalmol 200412217–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shih C Y, Graff Zivin J S, Trokel S L.et al Clinical significance of central corneal thickness in the management of glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol 20041221270–1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sobottka Ventura A C, Walti R.et al Corneal thickness and endothelial density before and after cataract surgery. Br J Ophthalmol 20018518–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muir K W, Jin J, Freedman S F. Central corneal thickness and its relationship to intraocular pressure in children. Ophthalmology 20041112220–2223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herse P, Yao W. Variation of corneal thickness with age in young New Zealanders. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 199371360–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siu A, Herse P. The effect of age on human corneal thickness. Statistical implications of power analysis. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 19937151–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herndon L W, Choudhri S A, Cox T.et al Central corneal thickness in normal, glaucomatous, and ocular hypertensive eyes. Arch Ophthalmol 19971151137–1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The Advanced Glaucoma Intervention Study Investigators Advanced Glaucoma Intervention Study: 2. Visual field test scoring and reliability. Ophthalmology 19941011445–1455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wickham L, Edmunds B, Murdoch I E. Central corneal thickness: will one measurement suffice? Ophthalmology 2005112225–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leske M C, Heijl A, Hussein M.et al Factors for glaucoma progression and the effect of treatment: the early manifest glaucoma trial. Arch Ophthalmol 200312148–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nemesure B, Wu S Y, Hennis A.et al Corneal thickness and intraocular pressure in the Barbados Eye Studies. Arch Ophthalmol 2003121240–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aghaian E, Choe J E, Lin S.et al Central corneal thickness of Caucasians, Chinese, Hispanics, Filipinos, African Americans, and Japanese in a glaucoma clinic. Ophthalmology 20041112211–2219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foster P J, Baasanhu J, Alsbirk P H.et al Central corneal thickness and intraocular pressure in a Mongolian population. Ophthalmology 1998105969–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brandt J D, Beiser J A, Kass M A.et al Central corneal thickness in the Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study (OHTS). Ophthalmology 20011081779–1788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Korey M, Gieser D, Kass M A.et al Central corneal endothelial cell density and central corneal thickness in ocular hypertension and primary open‐angle glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol 198294610–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rainer G, Findl O, Petternel V.et al Central corneal thickness measurements with partial coherence inferometry, ultrasound, and the Orbscan system. Ophthalmology 2004111875–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miglior S, Albe E, Guareschi M.et al Intraobserver and interobserver reproducibility in the evaluation of ultrasonic pachymetry measurements of central corneal thickness. Br J Ophthalmol 200488174–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hirji N K, Larke J R. Thickness of human cornea measured by topographic pachometry. Am J Optom Physiol Opt 19785597–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hara T, Hara T. Postoperative change in the corneal thickness of the pseudophakic eye: amplified diurnal variation and consensual increase. J Cataract Refract Surg 198713325–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cunliffe I A, Dapling R B, West J.et al A prospective study examining the changes in factors that affect visual acuity following trabeculectomy. Eye 19926618–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rainer G, Petternel V, Findl O.et al Comparison of ultrasound pachymetry and partial coherence inferometry in the measurement of central corneal thickness. J Cataract Refract Surg 2002282142–2145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]