Proliferative vitreoretinopathy (PVR) is a common cause of blindness after buckling procedures and after primary vitrectomy.1 PVR occurs in 10% of eyes after rhegmatogenous retinal detachment.2 Re‐detachment is seen mostly within the first 6–8 weeks after surgery. Efforts to reduce the risk of PVR include trying to reduce the surgical trauma, early surgery, and lower thresholds to use silicone oil or retinotomies, pharmaceutical adjuncts, as well as improvements in surgical technique during recent years.3

Surgeons are under the impression that the burden of PVR has lessened over recent decades. This is hypothetically attributable to a change in the surgical technique (for example, more primary vitrectomy instead of scleral buckling). To test this hypothesis, we have retrospectively analysed all patients who underwent primary surgery for rhegmatogenous retinal detachment in 1988 at the University of Cologne and compared the results to the patients operated on in 2003 in the same location. The follow up for eventual re‐operations was 1 year in both instances.

In a second step, all vitreoretinal operations, including those for retinal detachment and other indications, were counted in 1988 and 2003 to analyse whether the total number of operations changed compared to the number of re‐operations.

Case series

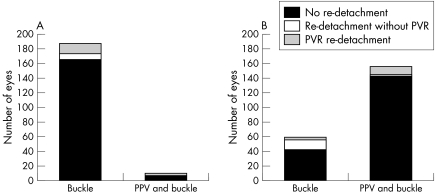

In 1988, a total of 197 eyes were operated for rhegmatogenous retinal detachment (fig 1A); 187 (95%, 187/197) of them were treated by buckling surgery. Out of these, re‐detachment occurred in 21 of the cases during 1 year of follow up (11.2%, 21/187). Primary vitrectomy combined with buckling surgery was performed in only 10 patients. Out of those, three (33%, 3/10) needed re‐operation for retinal re‐detachment.

Figure 1 Primary operations for rhegmatogenous retinal detachment in 1988 (A) and 2003 (B) and required re‐operations because of re‐detachment with or without PVR.

In 2003, in contrast, 157 of 217 eyes (72%) underwent primary PPV and buckling surgery (fig 1B). In 13 of these cases (8.3%, 13/157) re‐detachment of the retina was seen. Primary buckle without PPV was chosen for 60 eyes in 2003. Re‐detachment occurred in 17 eyes (28.3%, 17/60).

PVR, seen as star fold and membrane formation and defined as anterior and posterior PVR grade C leading to re‐detachment, was responsible for the described re‐detachment in three of 60 cases (5%) after buckling surgery in 2003 compared to 12 of 157 eyes (7.6%) after primary PPV and buckle. Thirteen of 187 cases (7%) operated with buckling surgery in 1988 showed PVR induced re‐detachment compared to three of 10 eyes (30%) after primary PPV and buckle. This high rate of PVR re‐detachments after primary PPV and buckle in 1988 could probably be explained by the fact that these were more complicated cases, which required the, in 1988, uncommon need for primary PPV in rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. Beside this, the number of PVR induced re‐detachment after primary operation for rhegmatogenous retinal detachment in 2003 did not decrease compared to 1988.

Nevertheless, the total number of re‐detachments is a little lower after primary PPV in 2003, with 8.3% (13/157) compared to 11.2% (21/187) in 1988 after buckling surgery alone (fig 1).

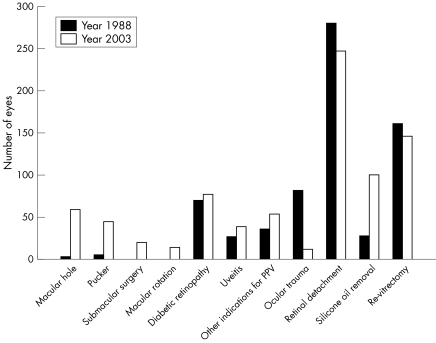

But why do surgeons have the subjective impression of a lower rate of PVR in everyday practice? To answer this question, we recorded all vitreoretinal operations, including those for rhegmatogenous retinal detachment, which are described above, but also those for other indications. While surgery for retinal detachment still remains the number one indication for surgery, the spectrum of diseases approached by vitreoretinal surgery widened during the past decade with increasing numbers of surgery for macular diseases (for example, macular pucker, macular hole, age related macular degeneration) (fig 2). Ocular trauma as a significant source of PVR complication is reduced. The more conscious use of protective eyewear and the seatbelt legislation have led to a reduction in cases with severe ocular trauma and intraocular foreign bodies in 2003 compared to 1988. There are fewer patients with severe ocular trauma in which PVR development is a frequent complication.2

Figure 2 All vitreoretinal operations performed in Cologne in the years 1988 (n = 692) and 2003 (n = 813).

In both years, re‐vitrectomy was necessary in nearly an equal number of eyes (18% (146/813) of all performed operations in 2003 compared to 23.3% (161/692) in 1988). This included reoperations because of PVR induced re‐detachment and re‐detachment without PVR, but also re‐vitrectomy because of macular pucker formation and others. Interestingly, in 2003, the indication for re‐vitrectomy more frequently included macular pucker formation (fig 2).

Comment

In summary, our data do not confirm the subjective impression of an improved rate of PVR in rhegmatogenous detachment in 2003 compared to 1988. The impression that PVR today is a decreasing problem may be explained by proportionally fewer interventions for PVR. The total number of operations and the number of new indications for surgery have grown, while ocular trauma and its PVR complication decreased.

Our results are supported by the SPR study,4 showing that primary vitrectomy did not reduce the risk of PVR over buckling. Our study is restricted by the limitations of a retrospective study. We also did not distinguish between phakic and pseudophakic eyes.

References

- 1.Heimann H, Zou X, Jandeck C.et al Primary vitrectomy for rhegmatogenous retinal detachment: an analysis of 512 cases. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2005261–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cardillo J A, Stout J T, LaBree L.et al Post‐traumatic proliferative vitreoretinopathy. The epidemiologic profile, onset, risk factors, and visual outcome. Ophthalmology 19971041166–1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kirchhof B. Strategies to influence PVR development. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2004242699–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.SPR Study Group Oral presentation at the SOE Meeting Berlin, September 2005. (Publication forthcoming)