Abstract

Objective

To report a retrospective analysis on the presence of hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), and transfusion transmitted virus (TTV) sequences in formalin fixed, paraffin embedded liver biopsies from eight patients with hepatocellular carcinoma, in comparison with blood markers.

Methods

A direct in situ polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technique was developed for the detection and localisation of genomic signals in the liver tissue. Conventional serological and molecular methods were used for blood evaluation.

Results

In situ PCR showed the presence of one of the three viruses (four HCV, two HBV, and one TTV) in seven of the eight patients. In addition, a co‐infection with HBV and HCV was detected in one patient. HCV and HBV sequences were located in the cytoplasm and the nucleus, respectively. When compared with blood markers, these findings were compatible with one occult HBV and two occult HCV infections.

Conclusions

These findings provide further evidence for occult HBV and HCV infections in cancerous tissues from patients with hepatocellular carcinomas. In situ PCR could be an additional tool for evaluating the viral aetiology of hepatocellular carcinoma alongside conventional diagnostic procedures.

Keywords: hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, transfusion transmitted virus, hepatocellular carcinoma

Hepatocellular carcinoma is the third leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide.1 The most frequent aetiology of liver cancer is hepatitis B virus (HBV), followed by hepatitis C virus (HCV), although other non‐viral causes play a role in a smaller proportion of cases. Among the other parenterally transmitted viruses, hepatitis G virus has never been associated with liver cancer,2 while transfusion transmitted virus (TTV) has been suggested as a possible risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with HCV related liver disorders.3

Patients with hepatocellular carcinoma living in endemic areas for HBV are often found to be positive for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) or anti‐HBc antibodies, or both, and this strong relation was the first epidemiological evidence of HBV related oncogenic transformation. Conversely, in developed countries the major concern is linked to HCV infection; in such areas the natural history of this virus, evolving from chronicity to cirrhosis, leads to its establishment as the main hepatocellular carcinoma risk factor.1,4 Several surveys have linked clinical and epidemiological evidence to the detection of genomic signals or replicative viral products in the liver tissue of patients previously exposed to, or currently infected by, these viruses, as proven by peripheral markers.5 However, the situation is further complicated by the dichotomy between the lack of serum markers of infection and the intrahepatic presence of active replicating viruses, indicating a condition known as “occult infection”.6,7 Occult HBV infection has long been recognised among patients with and without anti‐HBV antibodies.8,9 Recent data also suggest that when chronic hepatitis or cirrhosis of unexplained origin are explored by conventional diagnostic approaches, an intrahepatic HCV infection may be revealed.10,11

To define a viral role in the development of hepatocellular carcinoma, formalin fixed, paraffin embedded (FFPE) liver biopsies are considered a powerful source to study the correlation between viral infection and clinical outcome. Unfortunately, the process of storing tissues and extracting nucleic acids is subject to variability and has not been completely standardised. Thus, the use of extractive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) methodology, which is routinely employed in the evaluation of hepatocellular carcinoma tissues, does not assure the correct results, particularly when only a small amount of detectable virus is present in the tissue.

To enhance the sensitivity of PCR for detecting HCV, HBV, and TTV sequences in FFPE liver tissues, we have developed a direct “in situ PCR” method. We carried out a retrospective analysis on the concomitant presence of these hepatotropic viruses in hepatocellular carcinoma biopsies.12 Serological and molecular assays currently employed in the diagnosis were used as a comparative standard.

Methods

Patients and samples

This study was carried out retrospectively on FFPE liver tissue from eight cases of hepatocellular carcinoma (five men and three women), whose unthawed stored (−20°C) sera were available. The diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma was based on the histology findings, and only sections of cancer tissue were selected. The histological profiles included six patients with cirrhosis and two with modest necrotic‐inflammatory lesions and fibrosis. In all patients, hepatocellular carcinoma was associated with Child type A cirrhosis. Four patients had a history of alcohol intake (one <50 g/day, one 100 g/day, and two >150 g/day). Three patients reported major surgery. No exposure to blood transfusion or injecting drug use was recorded. None of patients had been treated with antiviral or immunosuppressive drugs before liver biopsy.

Conventional virological diagnosis

Anti‐HCV antibodies and HBV markers were tested by commercial enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; Roche GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). HCV RNA detection and genotyping, HBV DNA detection, and TTV DNA detection and sequencing were done as described previously.3

In situ PCR

The FFPE tissue sections were dewaxed in xylene for 20 minutes and then rehydrated to 100%, 90%, and 80% ethanol aqueous solutions. The slides were rinsed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) for eight minutes and permeabilised with 5 mg/μl of proteinase K solution (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany) in 0.01% Triton X‐100/PBS at 37°C for 30 minutes. After proteinase inactivation by heat (95°C for 60 seconds), slides were post‐fixed in 10% acetic acid for 60 seconds.

PCR for HBV and TTV was carried out in a Delphi 1000 thermal cycler, following the same amplification profile: 20 cycles at 95°C for 50 seconds, 60°C for four seconds, and 72°C for 50 seconds.

The mix was 10 mM Tris pH 8, 50 mM KCL, dTTP, dCTP, dGTP, dATP 200 μM each, 5 μM Cy3‐dCTP, primers 0.5 μM each, and 10 U of IS‐AmpliTaq (Perkin‐Elmer, Emerville, California, USA). The primers to HBV core region were: HBC1‐5′TTG CCT TCT GAC TTC TTT CC3′, HBC2‐5′TCT GCG AGG CGA GGG AGT TCT3′ (Dia Sorin, Saluggia, Italy). The amplicon size was 450 base pairs (bp).

TTV primers were NG133‐5′GTA AGT GAC CTT CCG AAT GGC TGA G3′, NG147‐5′GCC AGT CCC GAG CCC GAA TTG CC3′) as previously described.3 Slides were then counterstained with 20 μl of mounting medium with DAPI and analysed under a fluorescent microscope. For each experimental set, “no‐primers” and “no‐target” controls (human fibroblast cell cultures, as a true negative) were used.

For HCV in situ reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR), an overnight treatment with 50 U of RNA‐free Dnase (Celbio, Milan, Italy) at 37°C was necessary to eliminate all DNA after proteinase K digestion and inactivation. The RT reaction, containing antisense specific primer for 5′UTR region, was done with MMULV reverse transcriptase for 30 minutes at 42°C and then the sections were post‐fixed. The amplification profile was 20 cycles at 95°C for 50 seconds, 52°C for 40 seconds, and 72°C for 50 seconds. The reaction mix and the protocol were the same as used for HBV and TTV. The primers, 200 μM each, were: 5′UTR HCV1: 5′GCG ACC CAA CAC TAC TCG GCT3′ and HCV2: 5′ATG GCA TTA GTA TGA GTC3′ (Dia Sorin, Saluggia, Italy) The amplicon size was 187 bp.

The no‐RT step, no‐primers, and no‐target controls were included in each experiment.

Results

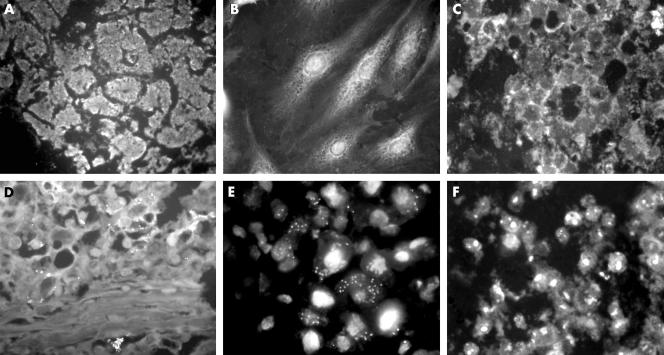

Table 1 shows the results obtained from the FFPE liver biopsy and the serum from each case. Typical findings of in situ PCR for the three viruses are shown in fig 1.

Table 1 Blood findings and liver in situ polymerase chain reaction for hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, and transfusion transmitted virus in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma.

| Case | HCV | HBV | TTV | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ab | RNA | IS PCR | HBs‐Ag | HBc Ab | DNA | IS PCR | DNA | IS PCR | |

| 1 | Neg | Neg | Neg | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg |

| 2 | Neg | Neg | Neg | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg |

| 3 | Pos | Pos* | Pos | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg |

| 4 | Neg | Neg | Pos | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg |

| 5 | Pos | Pos* | Pos | Neg | Pos | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg |

| 6 | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg | Pos | Neg | Neg | Pos | Pos |

| 7 | Pos | Pos* | Pos | Neg | Pos | Neg | Neg | Neg | Neg |

| 8 | Neg | Neg | Pos | Neg | Pos | Neg | Pos | Neg | Neg |

*Genotype 1b.

Ab, antibody; HBs‐Ag, hepatitis B surface antigen; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HBC, hepatitis C virus; IS PCR, in situ polymerase chain reaction; TTV, transfusion transmitted virus.

Figure 1 Typical findings for hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), and transfusion transmitted virus (TTV) and the controls by in situ polymerase chain reaction (PCR). (A) No primers control. (B) No target control. (C) No reverse transcriptase (RT) control. (D) TTV in situ PCR. (E) HCV in situ PCR. (F) HBV in situ PCR.

Anti‐HCV antibodies and sequences of core and 5′UTR regions of HCV subtype 1b were detected in the serum of patients 3, 5, and 7. The other patients tested negative both for anti‐HCV antibodies and for HCV genome by extractive PCR.

As regards HBV infection, six of the eight patients had anti‐HBc antibodies. Two patients (patient 1 and 2) were currently infected as they tested positive by both HbsAg and HBV‐DNA. The other anti‐HBc positive patients had different levels of anti‐HBs (range 15 to >1000 IU/ml; data not shown), indicating viral clearance at least at peripheral level.

The 5′UTR region of the TTV genome was amplified only in patient 6; the alignment of the nucleotide sequence analysis confirmed the fragment's specificity and matching with the TTV san‐S039 strain (Gene Bank accession number AB038620).

The in situ PCR on liver biopsies detected signals for the 5′UTR region of the HCV genome in five cases. Three of these were infected with 1b subtype (patients 3, 5, and 7), while two (patients 4 and 8) tested negative for anti‐HCV and HCV‐RNA in the serum. The fluorescent products of amplification were detected in the cytoplasm of hepatocytes.

HBV signals were detected in the nucleus of the hepatocytes by in situ PCR in three patients. Two were also positive for HBV DNA in the serum (patients 1 and 2), and the third was positive only for anti‐HBc antibodies (patient 8).

In the patient who was viraemic by TTV, the DNA was detected in the nuclei of transforming cells.

Collectively, seven of the eight patients with hepatocellular carcinoma showed the presence of a single virus type at the cellular level: four HCV, two HBV, and one TTV. In addition, a co‐infection by HBV and HCV was detected in the liver of one patient.

Discussion

An in situ PCR technique has been developed for the concomitant detection of HBV, HCV, and TTV footprints in FFPE liver biopsies of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. By overcoming the critical step of nucleic acids extraction from FFPE tissue, this technique is capable of better preservation of the nucleic acids from degradation and maintains tissue morphology intact, highlighting the area in normal or tumour tissue where the amplification occurs. The increased sensitivity of this assay when compared with hybridisation techniques is crucial for archival samples where a small amount of the viral target sequences is probably present. However, as a gold standard does not exist, caveats are needed for the specificity of the reaction. To address this point, each phase of the assay underwent proper controls—“no‐RT”, “no‐Taq”, “no‐primers”, and “no‐target” specificity controls—thus excluding stepwise false positive results and the presence of background noise.

Using this technique, we detected genomic signals for a single species of hepatotropic virus in the liver tissues of seven of eight patients: four were affected by HCV, two by HBV, and one by TTV. The co‐presence of HBV and HCV footprints was detected in one patient. These findings are consistent with various surveys aiming at revealing by in situ amplification procedures the presence of a unique virus, either HBV13 or HCV14,15,16 or TTV.3 Moreover, the overall pattern described here is in line with the findings of a larger series where multiple hepatotropic viruses were sought by extractive PCR.2 Abe et al reported that in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma from Japan and western countries, HCV infection was the most prevalent (around 40–60%) and that the genotype 1b was the most common, in contrast with other Asian countries where HBV was more commonly involved. A concomitant infection by HBV and HCV was present in 3% of the subjects, while no sequence of the investigated viruses (HBV, HCV, and HGV) was detected in about 5% of liver tissues.2 Thus it seems possible that TTV may account at least for a proportion of the “cryptogenetic” forms of hepatocellular carcinoma.

Take home messages

The findings provide further evidence for the existence of occult HBV and HCV infections in cancerous tissues from patients with hepatocellular carcinomas.

In situ PCR could be an additional tool for evaluating the viral aetiology of hepatocellular carcinoma alongside conventional diagnostic procedures.

A significant finding of our study was the discovery of occult infections sustained by both HBV and HCV. In one case, a virological pattern suggestive of an occult HBV infection was demonstrated. The patient, who tested positive for the HBV genome in the hepatocyte nuclei, had a serological profile (HbsAg negative, DNA negative, anti‐HBc and anti‐HBs positive) that denoted a previous exposure to HBV and was compatible with a typical occult infection.9 Moreover, in the same biopsy, the in situ PCR revealed HCV sequences, though serological and virological specific markers were undetectable in serum. This pattern was found in another patient who showed specific HCV sequences in the liver by in situ PCR but tested repeatedly negative for anti‐HCV antibodies and HCV‐RNA in sera.

While the concept of “occult” HBV infection is now established and accepted, detection of the HCV footprint in the liver in the absence of any peripheral marker has rarely been reported and is still debated. Apart from technical issues concerning the sensitivity of the methods used, several hypotheses may be advanced to explain the dichotomy between the liver findings and the peripheral blood findings. With regard to the untraceable HCV antibodies, a complete seroreversion and a lack of HCV viraemia among subjects infected for more than one decade has been described.17,18 Furthermore, an undetectable HCV‐RNA in serum during hepatocellular carcinoma could be linked to a suboptimal environment for viral replication because of replacement of normal cells by tumour cells.19 More convincingly, Castillo et al recently reported a series of “true occult HCV infections” in patients with longstanding abnormal liver function or steatosis of unexplained origin, where HCV‐RNA was revealed by extractive PCR and located in the hepatocyte cytoplasm by hybridisation. Conversely, in approximately 30% of the infected patients, HCV‐RNA was not detectable even in the most sensitive peripheral substrate (peripheral blood mononuclear cells).20 Because of the nature of the retrospective study, this issue could not be addressed, as no fresh blood samples were available. Thus the concept of occult HCV infection seems now tenable, at least on the basis of current methods for revealing peripheral HCV markers, though the exact significance of this condition—whether it is a true infection or the innocent presence of genomic signals—remains to be clarified.10

In conclusion, our findings provide further evidence for the possible existence of occult HBV and HCV infections in the liver. Because of its probable greater sensitivity when used with FFPE samples, the in situ PCR methodology may be an additional tool for improved evaluation of the viral aetiology in hepatocellular carcinoma patients alongside conventional procedures.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the grant RC 50/03 from IRCCS Burlo Garofolo, Trieste and by grants from Centro Studi Fegato, Trieste, Italy.

Abbreviations

HBsAg - hepatitis B surface antigen

HBV - hepatitis B virus

HCV - hepatitis C virus

TTV - transfusion transmitted virus

References

- 1.Llovet J M, Burroughs A, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet 20033621907–1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abe K, Edamoto Y, Park Y N.et al In situ detection of hepatitis B, C, and G virus nucleic acids in human hepatocellular carcinoma tissues from different geographic regions. Hepatology 199828568–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Comar M, Ansaldi F, Morandi L.et al In situ polymerase chain reaction detection of transfusion‐transmitted virus in liver biopsy. J Viral Hepat 20029123–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donato F, Tagger A, Chiesa R.et al Hepatitis B and C virus infection, alcohol drinking, and hepatocellular carcinoma: a case‐control study in Italy. Brescia HCC Study. Hepatology 199726579–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Block T M, Metha A S, Fimmel C J.et al Molecular viral oncology of hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogene 2003225093–5107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmidt W N, Wu P, Cederna J.et al Surreptitious hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection detected in the majority of patients with cryptogenic chronic hepatitis and negative HCV antibody tests. J Infect Dis 199717627–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kondili L A, Chionne P, Costantino A.et al Infection rate and spontaneous seroreversion of anti‐hepatitis C virus during the natural course of hepatitis C virus infection in the general population. Gut 200250693–696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bréchot C, Thiers V, Kremsdorf D.et al Persistent hepatitis B virus infection in subjects without hepatitis B surface antigen: clinically significant or purely “occult”? Hepatology 200134194–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cacciola I, Pollicino T, Squadrito G.et al Occult hepatitis B virus infection in patients with chronic hepatitis C liver disease. N Engl J Med 199934122–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lerat H, Hollinger F B. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) occult infection or occult HCV RNA detection? J Infect Dis 20041893–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Volker D, von Both I, Muller M.et al Detection of hepatitis C virus in paraffin‐embedded liver biopsies of patients negative for viral RNA in serum. Hepatology 199929223–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Comar M, Wiesenfeld U, Variola F.et al HPV‐direct in situ PCR: an advanced molecular tool in the screening of cervical cancer. Ann Ig 200113581–586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shieh B, Lee S E, Tsai Y C.et al Detection of hepatitis B virus genome in hepatocellular carcinoma tissues with PCR‐in situ hybridization. J Virol Methods 199980157–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walker F M, Dazza M C, Dauge M C.et al Detection and localization by in situ molecular biology techniques and immunohistochemistry of hepatitis C virus in livers of chronically infected patients. J Histochem Cytochem 199846653–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bettinger D, Mougin C, Fouqué B.et al Direct in situ reverse transcriptase‐linked polymerase chain reaction with biotinylated primers for detection of hepatitis C virus RNA in liver biopsies. J Clin Virol 199912233–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Su Y H, Lu S L, Gu Y H.et al In situ RT‐PCR detection of hepatitis C virus genotypes in Chinese patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 200221591–598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takaki A, Wiese M, Maertens G.et al Cellular immune responses persist and humoral responses decrease two decades after recovery from a single‐source outbreak of hepatitis C. Nat Med 20006578–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mazzeo C, Azzaroli F, Giovanelli S.et al Ten year incidence of HCV infection in northern Italy and frequency of spontaneous viral clearance. Gut 2003521030–1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yokosuka O, Kojima H, Imazeki F. Spontaneous negativation of serum hepatitis C virus RNA is a rare event in type C chronic liver diseases: analysis of HCV RNA in 320 patients who were followed for more than 3 years. J Hepatol 199931394–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Castillo I, Pardo M, Bartolomé J.et al Occult hepatitis C virus infection in patients in whom the etiology of persistently abnormal results of liver‐functions tests is unknown. J Infect Dis 20041897–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]