Abstract

Background

Placental trophoblast can be considered to be pseudomalignant tissue and the pathogenesis of gestational trophoblastic diseases remains to be clarified.

Aims

To examine the role of caspases 8 and 10, identified by differential expression, on trophoblast tumorigenesis.

Methods

cDNA array hybridisation was used to compare gene expression profiles in choriocarcinoma cell lines (JAR, JEG, and BeWo) and normal first trimester human placentas, followed by confirmation with quantitative real time polymerase chain reaction and immunohistochemistry. Caspase 10 and its closely related family member caspase 8 were analysed.

Results

Downregulation of caspase 10 in choriocarcinoma was detected by both Atlas™ human cDNA expression array and Atlas™ human 1.2 array. Caspase 10 mRNA expression was significantly lower in hydatidiform mole (p = 0.035) and chorioarcinoma (p = 0.002) compared with normal placenta. The caspase 8 and 10 proteins were expressed predominantly in the cytotrophoblast and syncytiotrophoblast, respectively, with significantly lower expression in choriocarcinomas than other trophoblastic tissues (p < 0.05). Immunoreactivity for both caspase 8 and 10 correlated with the apoptotic index previously assessed by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase mediated dUTP nick end labelling (p = 0.02 and p = 0.04, respectively) and M30 (p < 0.001 and p = 0.003, respectively) approaches.

Conclusions

These results suggest that the downregulation of capases 8 and 10 might contribute to the pathogenesis of choriocarcinoma.

Keywords: cDNA array, caspases, choriocarcinoma, hydatidiform mole

Gestational trophoblastic disease (GTD) encompasses a heterogeneous set of diseases arising from abnormal trophoblast tissue, and includes hydatidiform mole (HM), invasive mole, choriocarcinoma (CCA), placental site trophoblastic tumour, and epithelioid trophoblastic tumour. HM mole can be subclassified into complete HM and partial HM. GTD is a unique disease that arises from allografting of the conceptus, and has the potential for local invasion and widespread metastasis, with varying degrees of aggressiveness. Although CCAs are highly malignant, most HMs regress spontaneously after suction evacuation, although about 8–30% of patients with HM will develop persistent gestational trophoblastic neoplasia (GTN), as reflected by persistent or rising human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG) concentrations, and will require chemotherapy. The pathogenesis of GTD remains unclear and few parameters have been found to be useful in predicting the outcome of HM.

“Gestational trophoblastic disease is a unique disease that arises from allografting of the conceptus, and has the potential for local invasion and widespread metastasis, with varying degrees of aggressiveness”

cDNA array analysis can be used to investigate the expression profile of genes involved in human carcinogenesis, cell cycle regulation, apoptosis, transcription regulation, DNA repair and synthesis, and receptor signalling, in addition to growth factors and cell adhesion molecules, and perhaps lead to a better understanding of disease.1

In our previous studies, we demonstrated the differential expression of individual oncogenes in GTD,2,3,4,5 and showed that telomerase activity and apoptosis are probably related to the clinical outcome of HM.2,6,7 Recently, we used apoptotic cDNA arrays, and identified Mcl‐1, an apoptosis related gene, as being related to the clinical progression of HM.8 In our present study, we compared the gene expression profiles of normal first trimester placentas and choriocarcinoma cell lines using more comprehensive cDNA arrays, followed by confirmatory gene expression studies by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR) and immunohistochemistry. The results were correlated with the clinicopathological and biological parameters in an attempt to improve our understanding of the pathogenesis of GTD.

Materials and methods

Tissues and cell lines

JAR, JEG, and BeWo CCA cell lines available from ATCC (American Type Culture Collection, Maryland, USA) were cultured.

HMs were treated by suction evacuation after ultrasound and clinical diagnosis. First trimester placentas, second trimester placentas, and term placentas were collected after induced abortion or term delivery. Some tissues were snap frozen and stored at −70°C until RNA extraction. Approval was obtained from the ethics committee of the University of Hong Kong for the collection of placental tissue and tissue from gestational trophoblastic disease. Clinical follow up data were retrieved in patients with a diagnosis of HM. GTN was diagnosed if there was a plateau in the hCG concentration for four weeks or if there was a further increase in the hCG concentration for three consecutive weeks.9

Pooled RNA from three first trimester placentas (gestational age, 8–10 weeks) and three CCA cell lines were used for the cDNA array experiments. For the real time RT‐PCR experiments, nine first trimester placentas (gestational age, 7–12 weeks), two second trimester placentas (gestational age, 18–20 weeks), and four term placentas (gestational age, 38–41 weeks), in addition to 13 HMs that regressed (gestational age, 7–24 weeks) and six HMs that developed GTN (gestational age, 6–20 weeks) were used. Among the HMs that developed GTN, two patients developed metastasis to the lungs and one patient had an additional metastasis to the liver.

For the immunohistochemical study, formalin fixed, paraffin wax embedded tissues from 14 partial HMs (gestational age, 8–17 weeks), 34 complete HMs (gestational age, 8–28 weeks), and seven CCAs were selected randomly. In addition, 14 normal first trimester placentas (gestational age, 8–13 weeks), 13 term placentas (gestational age, 38–41 weeks), and 11 spontaneous abortions (gestational age, 5–12 weeks) were also included. Thirty two of the HMs spontaneously regressed after suction evacuation, whereas 16 patients developed GTN and required chemotherapy. The histological features of these cases were reviewed using haematoxylin and eosin stained sections.10,11,12 The diagnosis in most cases was confirmed by fluorescent microsatellite genotyping after microdissection and with chromosome in situ hybridisation to analyse ploidy status.13,14

RNA extraction and cDNA array analysis

Total RNA was extracted and the mRNA was then isolated using the QuickPrep Micro mRNA purification kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, UK). Frozen sections were histologically assessed to ensure that over 90% of the tissue was trophoblast. Equal amounts of pooled mRNA from three normal first trimester placentas (gestational age, 8–10 weeks) and three cell lines were used for probe synthesis. The differential gene expression experiments used the commercially available Atlas™ human cDNA expression array and the Atlas™ human 1.2 array (Clontech, Palo Alto, California, USA), which analysed 588 and 1176 cDNA tags, respectively, related to a wide range of biological pathways. The probes were labelled with [α‐33P]dATP, hybridised on to the membranes, washed, and exposed to x ray films. The intensities of the dotted genes were measured with AtlasImageTM (Clontech).

Real time RT‐PCR

Primers and TaqMan probes were designed to span three exons so that they were specific to the target transcripts and to eliminate amplification from genomic DNA. Caspase 8: (exon 6) forward primer, 5′‐CCG CAA AGG AAG CAA GAA C‐3′; (exon 8) reverse primer, 5′‐AAT TCT GAT CTG CTC ACT TCT TCT G‐3′; and TaqMan probe, 5′‐FAM‐TGC CTT GAT GTT ATT CCA GAG ACT CCA GGA‐TAMRA‐3′ (accession number NM_001228). Caspase 10: (exon 3) forward primer, 5′‐CAG AAG GCA TTG ACT CAG AGA ACT‐3′; (exon 5) reverse primer, 5′‐GAT ACG ACT CGG CTT CCT TGT‐3′; and TaqMan probe, 5′‐FAM‐CTT CCT TCT GAA AGA CTC GCT TCC‐TAMRA‐3′ (accession number NM_032974). The expression of caspases 8 and 10 was normalised against the expression of the housekeeping gene, TBP (TATA box binding protein).15 The quantitative real time reaction was carried out and analysed using the ABI7700 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California, USA).

Immunohistochemical staining of caspases 8 and 10

Paraffin wax embedded sections were incubated with primary goat polyclonal anticaspase 8 (p20; C‐20; Santa Cruz Biotech, Santa Cruz, California, USA) and rabbit polyclonal anticaspase 10 (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, California, USA). The sections were then developed with biotinylated secondary antibody (Amersham, Piscataway, New Jersey, USA), followed by streptavidin–biotin peroxidase complex (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark). Freshly prepared 3, 3‐diaminobenzidine was used for colour development and the sections were then counterstained with Mayer's haematoxylin.

Immunostaining for caspases 8 and 10 was scored with respect to relative intensity on an arbitrary scale: 1, weak; 2, moderate; and 3, intense. The percentage of positive cells was also estimated. The values of these two parameters were multiplied to produce an immunoreactive score, which ranged from 0 to 300 for each case.

Statistical analysis

Correlations between numerical data were performed using Pearson's correlation test. Numerical data that were not normally distributed were analysed by the Mann‐Whitney test and analysis of variance. A p value less than 0.05 was taken as significant.

Results

Downregulation of caspase 10 mRNA expression in CCA cell lines by cDNA array analysis

Genes with differential expression were defined as upregulated or downregulated if they displayed a twofold difference in expression. We found a twofold downregulation of caspase 10 using both the Atlas human cDNA expression array and the Atlas human 1.2 array (data not shown).

Reduced expression of caspases 8 and 10 in HM and CCA

Quantitative real time RT‐PCR confirmed the reduced expression of caspase 10 in HM (p = 0.035) and CCA (p = 0.002) when compared with normal placenta (data not shown).

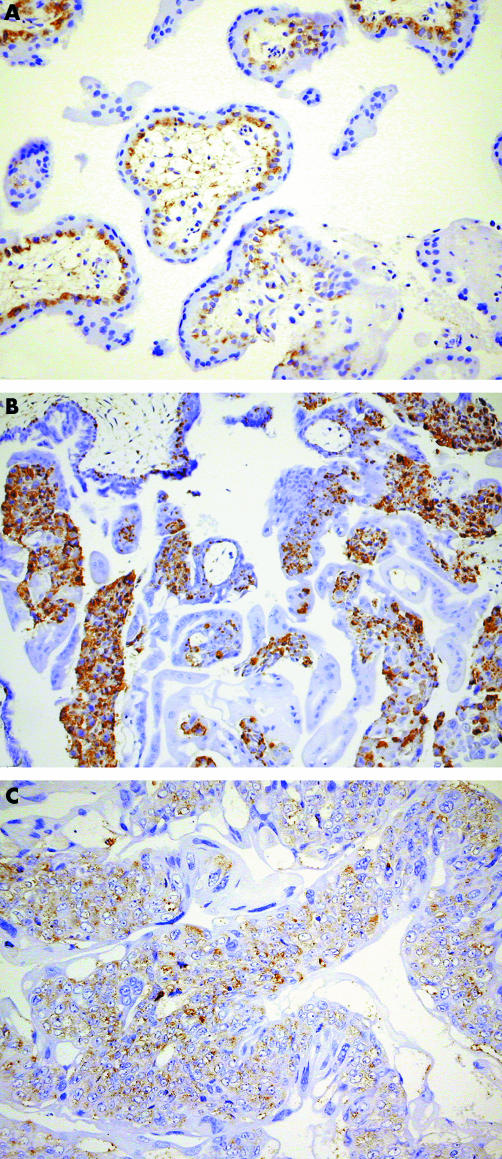

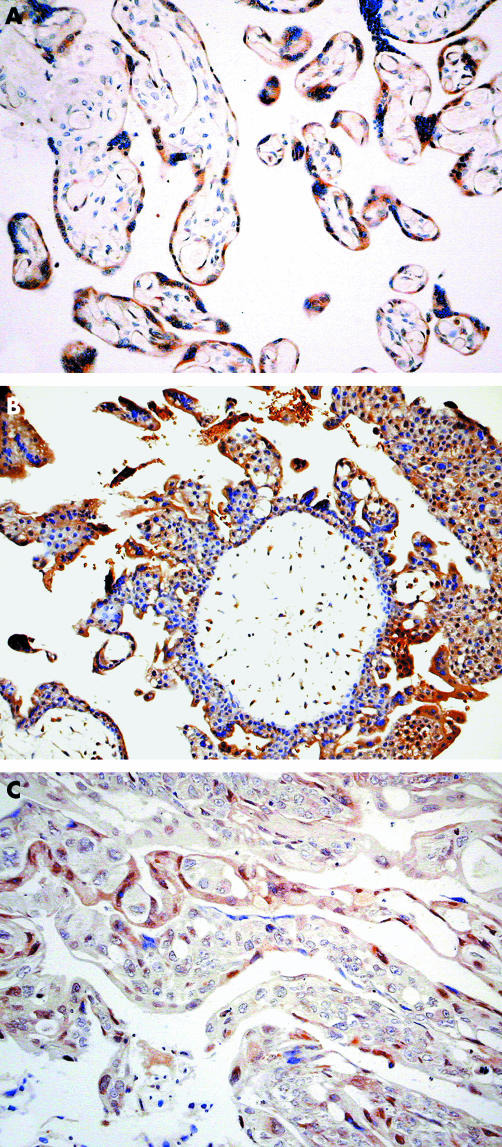

Immunohistochemical studies show that immunoreactivity for caspases 8 (fig 1) and 10 (fig 2) was found predominantly in the cytoplasm of the cytotrophoblast (CT) and syncytiotrophoblast (ST), respectively, in all the trophoblasts studied. No expression of caspase 8 was found in STs, whereas only weak expression of caspase 10 was found in CTs. Immunostaining for caspases 8 and 10 was weak in the intermediate trophoblast infiltrating the decidua.

Figure 1 Immunoreactivity for caspase 8 is found predominantly in the cytotrophoblast of (A) normal placenta, (B) hydatidiform mole, and (C) choriocarcinoma.

Figure 2 Immunoreactivity for caspase 10 is found predominantly in the syncytiotrophoblast of (A) normal placenta, (B) hydatidiform mole, and (C) choriocarcinoma.

The amount of caspase 8 and caspase 10 protein was significantly lower (p < 0.05; tables 1–3) in CCA than in normal placenta, spontaneous abortion, partial HM, and complete HM. However, there were no significant difference among the last four categories except for the marginal difference in caspase 8 expression between normal placenta and spontaneous abortion.

Table 1 Caspase 8 index of normal placenta, spontaneous abortion, hydatidiform mole, and choriocarcinoma.

| Range | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal placenta (n = 27) | 40–225 | 139 | 65.9 |

| Spontaneous abortion (n = 11) | 5–180 | 71 | 50.5 |

| Partial mole (n = 14) | 40–225 | 115 | 63.8 |

| Complete mole (n = 34) | 20–240 | 115 | 55.4 |

| Choriocarcinoma (n = 7) | 15–60 | 30.7 | 15.4 |

Table 2 Caspase 10 index of normal placenta, spontaneous abortion, hydatidiform mole, and choriocarcinoma.

| Range | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal placenta (n = 27) | 60–150 | 120 | 26.2 |

| Spontaneous abortion (n = 11) | 40–240 | 110 | 53.7 |

| Partial mole (n = 14) | 60–255 | 127 | 64 |

| Complete mole (n = 34) | 60–255 | 115 | 60.2 |

| Choriocarcinoma (n = 7) | 10–55 | 34.2 | 17.4 |

Table 3 Comparison of caspase 8 and 10 immunoscore between normal placenta, spontaneous abortion, partial mole, complete mole, and choriocarcinoma.

| Caspase 8 | Caspase 10 | |

|---|---|---|

| Normal placenta v spontaneous abortion | 0.032* | 0.36 |

| Normal placenta v partial mole | 0.35 | 0.93 |

| Normal placenta v complete mole | 0.33 | 0.28 |

| Normal placenta v choriocarcinoma | 0.002* | 0.002* |

| Partial mole v spontaneous abortion | 0.79 | 0.60 |

| Partial mole v complete mole | 0.77 | 0.21 |

| Partial mole v choriocarcinoma | 0.001 | 0.001* |

| Complete mole v spontaneous abortion | 0.028* | 0.042* |

| Complete mole v choriocarcinoma | <0.001* | <0.001* |

| Spontaneous abortion v choriocarcinoma | 0.036* | 0.002* |

Values shown are p values (Mann Whitney test).

*Significant (p<0.05).

The expression of caspases 8 and 10 was not significantly different between the HMs that subsequently regressed and those that developed persistent GTN, with or without metastasis (p = 0.13 and p = 0.5, respectively). Therefore, there was no correlation between the expression of caspases 8 and 10 and the clinical behaviour of HM.

Correlation with apoptotic markers

The results were also correlated with our previous findings on apoptotic activity in matched samples.2,7 Caspase 8 and 10 immunoreactivity correlated with the apoptotic index, as assessed by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase mediated dUTP nick end labelling (TUNEL) (p = 0.02 and p = 0.04, respectively) or M30 (p < 0.001 and p = 0.003, respectively), but not with Bcl‐2 expression (p > 0.05).

Discussion

In our two independent cDNA array analyses, caspase 10 was found to be consistently downregulated in the CCA cell lines, and was thus selected for further analysis. Human first trimester placentas were used as controls in an attempt to reflect the in vivo situation more closely. Decreased expression of heat shock protein 27 was also seen in CCA cell lines in our array study, which agrees with previous findings using a placenta cell line as control.16

Caspase 10, an initiator of death receptor signalling, is closely related to the sequence of caspase 8.17 The genes for these two molecules map to the same region of chromosome 2q33–34, so that they might arise from the duplication of one ancestral gene.18 Shikama detected both caspase 8 and caspase 10 in the cytoplasm of HeLa cancer cells.19 The expression of procaspases 8 and 10 in tumour cell lines was associated with TRAIL (tumour necrosis factor α related apoptosis inducing ligand) induced apoptosis and was important in the resistance to chemotherapy.20,21 Moreover, caspase 10 expression was found to be more abundant in fetal lung, kidney, and skeletal muscle but not in the corresponding adult tissues, suggesting that caspase 10 might also play an important role in fetal development.18,22

In our present study, we found significantly lower expression of caspase 8 and 10 mRNA and/or protein in CCA and HM compared with non‐molar placentas. Our results support the hypothesis that human cancer cells often have defects in apoptosis, including deficient expression of caspases.23,24 For example, downregulation of caspase 1 or 7 appears to be a marker of colonic cancer.25 In contrast, caspase overexpression may induce apoptosis in a prostate cancer cell line.26 Thus, the significant downregulation of caspases 8 and 10 detected in our study may play a role in the pathogenesis of GTD. However, no significant differences in the expression of caspases 8 and 10 were seen between regressive and persistent moles, suggesting that the expression of these caspases would not be a useful predictor of the clinical behaviour of HMs.

“Our results support the hypothesis that human cancer cells often have defects in apoptosis, including deficient expression of caspases”

Trophoblasts of the placenta can be considered to be “pseudomalignant” tissue because even normal trophoblasts display features of malignant cells, such as rapid proliferation, infiltration of host tissue, and haematogenous dissemination, and can escape immunological surveillance. Trophoblasts can be divided into CTs, STs, and intermediate trophoblasts. CTs consist of proliferating stem cells and subsequently differentiate and fuse to form STs. It has been found that different oncogenes are expressed differentially in CTs and STs.2,3,4,5,27,28,29 Our immunohistochemical staining analysis showed that caspase 8 expression was limited to CTs, whereas caspase 10 was expressed predominantly in STs.

With no generative potential, the formation of an ST depends upon the continuous fusion of the underlying proliferating CT to replace its aging population.28,29,30,31 This continuous fusion of stem cells also serves to transport fresh cellular materials such as nucleic acids and enzymes, which might include caspases, to the ST. In culture conditions, it was shown that CTs exhibit higher caspase 3, 6, 8, and 9 activity compared with the more differentiated STs,32 and that caspase 8 expression is a prerequisite for differentiation and syncytial fusion in CTs.33 Because caspase 10 was only weakly expressed in CTs but strongly expressed in STs, caspase 10 activity may start in the CT and accumulate during syncytial fusion at ST. Caspase 8 expression was found in CT only; it might become active in the CT but disappear once syncytial fusion is completed. Our previous findings from the M30 study also suggested that apoptosis involving the caspase cascade might be initiated in the CT and completed in the ST.7 These data appear to support the view that caspase 8 occupies an upstream position with respect to caspase 10 in the apoptotic pathway in trophoblasts. Alternatively, caspases 8 and 10 may have distinct roles in death receptor signalling34,35 in apoptosis initiation in different populations of trophoblasts.

The immunoreactivity of both caspase 8 and caspase 10 correlated with the apoptotic index in GTD assessed by the M30 and TUNEL approaches in our previous studies.2,7 The TUNEL technique identifies fragmented DNA formed as a result of DNA endonuclease activity and helps in assessing apoptosis at a late stage. The M30 monoclonal antibody recognises a formalin resistant caspase cleavage site within cytokeratin 18, after cleavage by caspases 3 and 7. A significant correlation between caspases 8 and 10 and both of these apoptotic activity indicators suggested that caspases 8 and 10 are important in the process of apoptosis. In contrast, neither caspases 8 nor caspase 10 expression correlated with that of Bcl‐2, suggesting that the expression of Bcl‐2 does not influence the expression of caspases 8 and 10 in GTD. Therefore, further studies to elucidate the relation between Bcl‐2 and specific caspases are essential.

Take home messages

We found significantly lower expression of caspase 8 and 10 mRNA and/or protein in choriocarcinoma and hydatidiform mole compared with non‐molar placentas

Immunoreactivity for both caspase 8 and caspase 10 correlated with the apoptotic index

Caspase 10 and its related family member caspase 8 are probably important in the regulation of apoptosis in trophoblastic tissues and the development of trophoblastic diseases

Apoptosis involving the caspase cascade might be initiated in the cytotrophoblast and completed in the chorionic villi of the syncytiotrophoblast

In summary, caspase 10 and its related family member caspase 8 are probably important in the regulation of apoptosis in trophoblastic tissues and the development of GTD. Apoptosis involving the caspase cascade might be initiated in the CT and completed in the chorionic villi of the ST stage.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a Research Council Grant (10203228.13396.21200.324.01). The authors thank Ms S Liu for technical advice and Mr SK Lau for photographic assistance.

Abbreviations

CCA - choriocarcinoma

GTD - gestational trophoblastic disease

GTN - gestational trophoblastic neoplasia

hCG - human chorionic gonadotrophin

HM - hydatidiform mole

PCR - polymerase chain reaction

RT - reverse transcription

TUNEL - terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase mediated dUTP nick end labelling

References

- 1.DeRisi J, Penland L, Brown P O.et al Use of a cDNA microarray to analyse gene expression patterns in human cancer. Nat Genet 199614457–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wong S Y, Ngan H Y, Chan C C.et al Apoptosis in gestational trophoblastic disease is correlated with clinical outcome and Bcl‐2 expression but not Bax expression. Mod Pathol 1999121025–1033. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheung A N Y, Srivastava G, Pittaluga S.et al Expression of c‐myc and c‐fms oncogenes in trophoblastic cells in hydatidiform mole and normal human placenta. J Clin Pathol 199346204–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheung A N Y, Shen D H, Khoo U S.et al p21WAF1/CIP1 expression in gestational trophoblastic disease: correlation with clinicopathological parameters, and Ki67 and p53 gene expression. J Clin Pathol 199851159–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheung A N Y, Shen D H, Khoo U S.et al Immunohistochemical and mutational analysis of p53 tumour suppressor gene in gestational trophoblastic disease: correlation with mdm2, proliferation index, and clinicopathologic parameters. Int J Gynecol Cancer 19999123–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheung A N Y, Zhang D K, Ngan Y S.et al Telomerase activity in gestational trophoblastic disease.J Clin Pathol 199952588–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chiu P M, Ngan Y S, Khoo U S.et al Apoptotic activity in gestational trophoblastic disease correlates with clinical outcome: assessment by the caspase‐related M30 CytoDeath antibody. Histopathology 200138243–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fong P Y, Xue W C, Ngan H Y.et al Mcl‐1 expression in gestational trophoblastic disease correlates with clinical outcome. Cancer 2005103268–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong L C, Ngan H Y S, Cheng D K L.et al Methotrexate infusion in low‐risk gestational trophoblastic disease. Am J Obstet Gynecol 20001831579–1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shih I M, Mazur M T, Kurman R J. Gestational trophoblastic disease and related lesions. In: Kurman RJ, ed. Blaustein's pathology of the female genital tract. New York: Springer Verlag, 20021193–1247.

- 11.Cheung A N. Pathology of gestational trophoblastic diseases. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 200317849–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paradinas F J, Elston C W. Gestational trophoblastic diseases. In: Fox H, Wells M, eds. Haines and Taylor obstetrical and gynaecological pathology. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 20031359–1430.

- 13.Lai C Y, Chan K Y, Khoo U S.et al Analysis of gestational trophoblastic disease by genotyping and chromosome in situ hybridization. Mod Pathol 20041740–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheung A N Y, Khoo U S, Lai C Y L.et al Metastatic trophoblastic disease following initial diagnosis of partial hydatidiform mole: genotyping and chromosome in situ hybridization analysis. Cancer 20041001411–1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chan K Y, Ozcelik H, Cheung A N.et al Epigenetic factors controlling the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes in sporadic ovarian cancer. Cancer Res 2002624151–4156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vegh G L, Fulop V, Liu Y.et al Differential gene expression pattern between normal human trophoblast and choriocarcinoma cell lines: downregulation of heat shock protein‐27 in choriocarcinoma in vitro and in vivo. Gynecol Oncol 199975391–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen G M. Caspases: the executioners of apoptosis. Biochem J 19973261–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fernandes‐Alnemri T, Armstrong R C, Krebs J.et al In vitro activation of CPP32 and Mch3 by Mch4, a novel human apoptotic cysteine protease containing two FADD‐like domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1996937464–7469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shikama Y. Comprehensive studies on subcellular localizations and cell death‐inducing activities of eight GFP‐tagged apoptosis‐related caspases. Exp Cell Res 2001264315–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petak I, Douglas L, Tillman D M.et al Pediatric rhabdomyosarcoma cell lines are resistant to Fas‐induced apoptosis and highly sensitive to TRAIL‐induced apoptosis. Clin Cancer Res 200064119–4127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eggert A, Grotzer M A, Zuzak T J.et al Resistance to tumour necrosis factor‐related apoptosis‐inducing ligand (TRAIL)‐induced apoptosis in neuroblastoma cells correlates with a loss of caspase‐8 expression. Cancer Res 2001611314–1319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ng P W, Porter A G, Janicke R U. Molecular cloning and characterization of two novel pro‐apoptotic isoforms of caspase‐10. J Biol Chem 199927410301–10308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martinez‐Lorenzo M J, Gamen S, Etxeberria J.et al Resistance to apoptosis correlates with a highly proliferative phenotype and loss of Fas and CPP32 (caspase‐3) expression in human leukemia cells. Int J Cancer 199875473–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kolenko V, Uzzo R G, Bukowski R.et al Dead or dying: necrosis versus apoptosis in caspase‐deficient human renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Res 1999592838–2842. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jarry A, Vallette G, Cassagnau E.et al Interleukin 1 and interleukin 1beta converting enzyme (caspase 1) expression in the human colonic epithelial barrier. Caspase 1 downregulation in colon cancer. Gut 199945246–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marcelli M, Cunningham G R, Walkup M.et al Signaling pathway activated during apoptosis of the prostate cancer cell line LNCaP: overexpression of caspase‐7 as a new gene therapy strategy for prostate cancer. Cancer Res 199959382–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hammer A, Blaschitz A, Daxbock C.et al Fas and Fas‐ligand are expressed in the uteroplacental unit of first‐trimester pregnancy. Am J Reprod Immunol 19994141–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huppertz B, Frank H G, Kingdom J C.et al Villous cytotrophoblast regulation of the syncytial apoptotic cascade in the human placenta. Histochem Cell Biol 1998110495–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huppertz B, Frank H G, Reister F.et al Apoptosis cascade progresses during turnover of human trophoblast: analysis of villous cytotrophoblast and syncytial fragments in vitro. Lab Invest 1999791687–1702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adler R R, Ng A K, Rote N S. Monoclonal antiphosphatidylserine antibody inhibits intercellular fusion of the choriocarcinoma line, JAR. Biol Reprod 199553905–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huppertz B, Hunt J S. Trophoblast apoptosis and placental development—a workshop report. Placenta 200021(suppl A)S74–S76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yusuf K, Smith S D, Sadovsky Y.et al Trophoblast differentiation modulates the activity of caspases in primary cultures of term human trophoblasts. Pediatr Res 200252411–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Black S, Kadyrov M, Kaufmann P.et al Syncytial fusion of human trophoblast depends on caspase 8. Cell Death Differ 20041190–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang J, Chun H J, Wong W.et al Caspase‐10 is an initiator caspase in death receptor signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 20019813884–13888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kischkel F C, Lawrence D A, Tinel A.et al Death receptor recruitment of endogenous caspase‐10 and apoptosis initiation in the absence of caspase‐8. J Biol Chem 200127646639–46646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]