Abstract

Background

The Toll‐like receptor (TLR) family recognises pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and plays a pivotal role in the innate immune response. Biliary epithelial cells (BECs) lining the intrahepatic bile ducts are potentially exposed to bacterial components in bile, and murine BECs possess TLRs that recognise PAMPs, resulting in nuclear factor κB (NF‐κB) activation.

Aims

To examine the presence of TLRs in human BECs and the influence of cytokines and PAMPs on TLR expression and NF‐κB activation.

Methods

The expression of TLR2–5, MD‐2, MyD88, and IRAK1 was examined in human liver tissue and cultured BECs by immunohistochemistry or reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction. The influence of PAMPs (peptidoglycan and lipopolysaccharide) in cultured cells preincubated with interferon γ (IFNγ) was evaluated by NF‐κB activation.

Results

TLR2–5, MyD88, and IRAK‐1 proteins were detectable in BECs of the intrahepatic biliary tree in human liver tissue. TLR2–5, MD‐2, MyD88, and IRAK‐1 mRNA was demonstrated in human cultured BECs. The expression of these TLRs was upregulated by IFNγ, and TLR2 was upregulated by tumour necrosis factor α. Interleukins 4 and 6 failed to induce TLR upregulation. Interestingly, preincubation with IFNγ synergistically increased the upregulation of NF‐κB induced by PAMPs in cultured BECs.

Conclusion

These results suggest that the TLR family is present in human biliary cells and participates in the innate immunity of the intrahepatic biliary tree. Disordered regulation of TLRs after intracellular signalling by cytokines and PAMPs may be involved in immune mediated biliary diseases.

Keywords: innate immunity, biliary epithelial cells, Toll‐like receptor, pathogen associated molecular patterns

The intrahepatic biliary tree is a conduit through which bile passes to the extrahepatic bile duct.1 There have been several reports that pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS), lipoteichoic acids, and bacterial DNA fragments are detectable in bile,2,3,4,5,6,7,8 suggesting that the biliary epithelium may be exposed to these PAMPs. Biliary epithelial cells (BECs) produce various proinflammatory cytokines including interleukin 6 (IL‐6) and tumour necrosis factor α (TNFα) when treated with LPS and cytokines.5,9,10 Moreover, the T cell derived cytokine milieu around bile ducts is associated with the aberrant expression of immune regulating molecules in affected bile ducts and the pathogenesis of inflammatory biliary diseases, such as primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC).9,11,12

“Recently, we demonstrated that Toll‐like receptor molecules are involved in biliary innate immunity using cultured murine biliary epithelial cells”

The Toll‐like receptor (TLR) family plays a crucial role in the innate recognition of PAMPs.13 To date, 10 TLRs (TLR1–10) have been identified. TLR2 is responsible for the recognition of peptidoglycan (PGN) and lipoteichoic acid, whereas TLR4 recognises LPS.6,8 These responses to PAMPs transduce intracellular signals, leading to nuclear factor κB (NF‐κB) translocation, which results in the synthesis of inflammatory cytokines such as TNFα.5,7,8,14,15 Epithelial cells lining the mucosal surface of the gastrointestinal tract16,17 and urogenital tract18 and immunocompetent cells have been shown to possess innate immunity involving TLR systems.

Recently, we demonstrated that Toll‐like receptor molecules are involved in biliary innate immunity using cultured murine BECs.5 In our present study, we examined the expression of TLRs in human biliary epithelium, the responsiveness to PAMPs, and the influence of cytokines using cultured human BECs, assuming that the TLR system of the biliary tree is involved in innate immunity and cytokine mediated inflammatory reactions in the intrahepatic biliary tree.

Materials and methods

Liver tissue specimens

Liver specimens from eight histologically normal livers (mean age, 58 years; male/female, three/five), 23 cases of PBC (stage I/II/III/IV, 10/eight/one/four; mean age, 60 years; male/female, two/21), 11 cases of extrahepatic biliary obstruction (EBO; mean age, 68 years; male/female, seven/four), and 26 cases of hepatitis C virus related liver cirrhosis (HCV‐LC; mean age, 65 years; male/female, 16/10) were obtained from the liver disease file of our laboratory. Formalin fixed, paraffin wax embedded sections were prepared for immunohistochemistry.

Among the fresh human liver tissues investigated, samples from four normal livers (non‐cancerous parts obtained from surgically resected livers of metastatic liver tumour), four HCV‐LCs, and five PBCs (explanted livers) were used for reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR). Frozen sections were prepared for microdissection from one normal liver, two PBCs, and one HCV‐LC. Informed consent was obtained from all patients before surgery.

Laser capture microscopy and RNA amplification

Approximately 100 cells lining bile ducts were microdissected from the frozen sections using Microdissection System PixCell™ II (Arcturus, Mountain View, California, USA). Total RNA was extracted and amplified using the PicoPure RNA isolation kit and RiboAmp™ RNA amplification kit (Arcturus), respectively.

Immunohistochemistry

Dewaxed sections heat treated in citrate buffer were incubated overnight with polyclonal rabbit antibodies against human TLR2–5 and intracellular adaptor molecules (MyD88 and IRAK‐1) (1 μg/ml, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, California, USA), and then with the ENVISON system (Dako, Tokyo, Japan) for one hour. After reacting with benzidine, sections were counterstained with haematoxylin. As a negative control, normal rabbit IgG (1 μg/ml) was used as the primary antibody; this always resulted in negative staining.

For the semiquantitative evaluation of TLR4, five representative septal or interlobular bile ducts1 were chosen in each case (40 bile ducts in normal livers, 115 in PBC, 55 in EBO, and 130 in HCV‐LC) for assessment, and were evaluated as cytoplasmic or cytoplasmic and membranous (luminal, lateral, and/or basal) expression.

RT‐PCR analysis

The expression of TLR2–5, MD‐2 (coreceptor of TLR4),15,17 MyD88, and IRAK‐1 mRNA in liver tissues, microdissected bile ducts, and cultured cells was detected by means of RT‐PCR. In cultured cells, mRNA encoding IL‐4, IL‐5, IL‐6, interferon γ (IFNγ), and TNFα receptors (IL‐4R, IL‐5R, IL‐6R, IFNγR, and TNFR1/2, respectively) was also examined. Total RNA from liver tissues and cultured cells, and amplified RNA from microdissected bile ducts, were used for reverse transcription. PCR was performed using DNA polymerase and specific primers (table 1); the PCR consisted of denaturation at 94°C (one minute), annealing (one minute), and extension at 72°C (two minutes) (table 1 shows the annealing temperatures and cycle numbers). Glyceraldehyde 3‐phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as an internal standard.

Table 1 Primer sequences for reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction.

| Forward | Reverse | Product size | Cycle number | Annealing temperature | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TLR2 | 5′‐ GCCAAAGTCTTGATTGATTGG ‐3′ | 5′‐ TTGAAGTTCTCCAGCTCCTG ‐3′ | 347 bp | 28 | 55°C |

| TLR3 | 5′‐ CCATTCCAGCCTCTTCGTAA ‐3′ | 5′‐ GGATGTTGGTATGGGTCTCG ‐3′ | 505 bp | 25 | 55°C |

| TLR4 | 5′‐ TGGATACGTTTCCTTATAAG ‐3′ | 5′‐ GAAATGGAGGCACCCCTTC ‐3′ | 507 bp | 28 | 55°C |

| TLR5 | 5′‐ GGAACCAGCTCCTAGCTCCT ‐3′ | 5′‐ GATGGCATCCTGGATATTGG ‐3′ | 575 bp | 28 | 55°C |

| MD‐2 | 5′‐ GTCCACCCTGTTTTCTTCCAT ‐3′ | 5′‐ GGGCTCCCAGAAATAGCTTC ‐3′ | 404 bp | 25 | 55°C |

| MyD88 | 5′‐ CCAACCTTCAGCAGTGACAA ‐3′ | 5′‐ GTGTGTATGCTGGTGCCTGT ‐3′ | 398 bp | 25 | 55°C |

| IRAK‐1 | 5′‐ GAGTGGACTGCAGTGAAGCA ‐3′ | 5′‐ CTACCACCCCAAAGCTGAAG ‐3′ | 499 bp | 25 | 55°C |

| IL‐4R | 5′‐ CAGAGAGCCTGTTCCTGGAC ‐3′ | 5′‐ CACAGTGGTTGGCTCAGAGA ‐3′ | 407 bp | 28 | 65°C |

| IL‐5R | 5′‐ CTCCACAAAGGCTTTTCAGC ‐3′ | 5′‐ CTCCCCAGTGTGTCTTTGCT ‐3′ | 308 bp | 40 | 55°C |

| IL‐6R | 5′‐ TGGACACTCACACGGACACT ‐3′ | 5′‐ GTGGGAGGTGGAGAAGAGAGA ‐3′ | 600 bp | 28 | 65°C |

| IFNγR | 5′‐ GGCAGCATCGCTTTAAACTC ‐3′ | 5′‐ CACCTGCTCACCTAGGAACC ‐3′ | 601 bp | 22 | 60°C |

| TNFR1 | 5′‐ GAGAGGCCATAGCTGTCTGG ‐3′ | 5′‐ GTTTTCTGAAGCGGTGAAGG ‐3′ | 303 bp | 35 | 60°C |

| TNFR2 | 5′‐ GGATGAAGCCCAGTTAACCA ‐3′ | 5′‐ TGTCCTGTCTTCATGGGTGA ‐3′ | 500 bp | 30 | 60°C |

| GAPDH | 5′‐ GGCCTCCAAGGAGTAAGACC ‐3′ | 5′‐ AGGGGTCTACATGGCAACTG ‐3′ | 147 bp | 18 | 60°C |

GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3‐phosphate dehydrogenase; IFNγR, interferon γ receptor; IL‐4/5/6R, interleukin 4/5/6 receptor; TLR, Toll‐like receptor; TNFR, tumour necrosis factor receptor.

For quantitative analysis, real time PCR was also performed according to a standard protocol using SYBR green and the ABI 7700 sequence detection system (ABI, Tokyo, Japan). Primers were newly designed to meet specific criteria using Primer Express Software (ABI).

Cultured cells

Two human intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) cell lines (CCKS119,20 and HuCCT121), and three human intrahepatic bile duct BEC cell lines (HIBEC1–3) were investigated. HIBEC1–3 are derived from explanted livers of one patient with HCV‐LC22 and two patients with PBC.5

Stimulators

Human IL‐4, IL‐6, IFNγ, and TNFα were purchased from PeproTech (London, UK). PGN (InvivoGen, San Diego, California, USA) and Ultra Pure LPS (InvivoGen) were used as ligands for TLR2 and TLR4, respectively. Cultured cells were treated with the cytokines (l000 U/ml) for three hours and then analysed by RT‐PCR.

Estimation of NF‐κB activation

Cultured cells were first treated with IFNγ for 36 hours and then continuously with PGN (1 μg/ml) or LPS (1 μg/ml) for two hours, after which NF‐κB activation was measured by the DNA binding capacity of NF‐κB using the TransAM™ NF‐κB kit (Active Motif, Carlsbad, California, USA).5,23 Treatment with IFNγ, PGN, or LPS alone was also examined.

Statistical analysis

The paired t test was used and significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

TLR expression in human liver tissue

Detection of TLR mRNA

Amplification of TLR2–5, MD‐2, MyD88, and IRAK‐1 mRNA was detected in all liver tissue and microdissected bile duct samples by RT‐PCR (fig 1).

Figure l Gel image of reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction for TLR2–5, MD‐2, MyD88, IRAK‐1, and GAPDH (positive control) mRNA in whole liver tissue from normal liver (lanes 1–4), PBC (lanes 5–9), and HCV‐LC (lanes 10–13), and in microdissected bile ducts of normal liver (lane 14), PBC (lanes 15 and 16), and HCV‐LC (lane 17). GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3‐phosphate dehydrogenase; HCV‐LC, hepatitis C virus related liver cirrhosis; PBC, primary biliary cirrhosis; TLR, Toll‐like receptor.

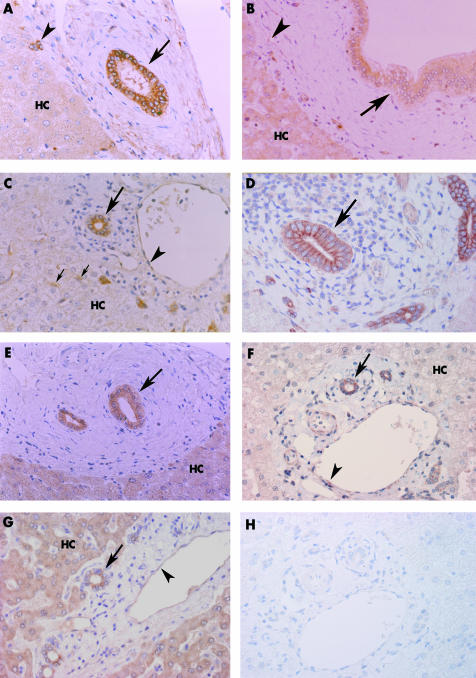

Expression of TLR protein

In normal liver, TLR2–5, MyD88, and IRAK‐1 were immunohistochemically expressed diffusely in the cytoplasm of the intrahepatic large bile ducts, septal bile ducts, interlobular bile ducts, bile ductules, and intrahepatic peribiliary glands1 (fig 2). Hepatocytes expressed TLR3, TLR5, and IRAK‐1. Endothelial cells in portal tracts expressed TLR3, TLR4, MyD88, and IRAK‐1. Several Kupffer cells were positive for TLR4 and MyD88.

Figure 2 Immunohistochemistry for TLR2–5, MyD88, and IRAK‐1 in normal liver (A–C, E–H) and PBC (D). (A) TLR2 was expressed in the cytoplasm of septal bile ducts (arrow) and bile ductules (arrowhead). Hepatocytes (HC) are faintly positive. (B) TLR3 was expressed in large bile ducts (arrow), endothelial cells (arrowhead), and hepatocytes. (C) TLR4 was expressed in the cytoplasm of interlobular bile ducts (large arrow), endothelial cells (arrowhead), and Kupffer cells (small arrows). Hepatocytes were faintly positive or negative. (D) Interlobular bile ducts (arrow) in PBC expressed TLR4 in the lateral and luminal surfaces in addition to the cytoplasm. (E) TLR5 was expressed in the cytoplasm of septal bile ducts (arrow) and hepatocytes. (F) MyD88 was expressed in interlobular bile ducts (arrow) and endothelial cells (arrowhead). Hepatocytes were faintly positive or negative. (G) IRAK‐1 was expressed in interlobular bile ducts (arrow), endothelial cells (arrowhead), and hepatocytes. (H) A semiserial section adjacent to that shown in (F). The positive signals were eliminated when the slide was incubated with normal rabbit IgG (negative control). PBC, primary biliary cirrhosis; TLR, Toll‐like receptor.

In the pathological livers, TLR2–5, MyD88, and IRAK‐1 were diffusely expressed in the cytoplasm of bile ducts, as seen in normal liver. Moreover, TLR4 was also expressed on the luminal, lateral, and basal surfaces of bile ducts in variable combinations in pathological livers (fig 2D). Membranous (luminal, lateral, and/or basal) and cytoplasmic expression of TLR4 was found in 15 of 40 bile ducts in normal liver, 92 of 115 in PBC, 44 of 55 in EBO, and 108 of 130 in HCV‐LC, with relative increased membranous staining in pathological livers (fig 3). TLR3 and MyD88 positive inflammatory cells were found scattered in the portal tracts.

Figure 3 Pattern of TLR4 expression in bile ducts. Five representative septal or interlobular bile ducts were chosen in each case for the assessment. Membranous (luminal, lateral, and/or basal) and cytoplasmic expression was found in 15 of 40 bile ducts in normal liver, 92 of 115 bile ducts in PBC, 44 of 55 bile ducts in EBO, and 108 of 130 bile ducts in HCV‐LC. Membranous and cytoplasmic expression was significantly increased in pathological livers, compared with normal liver (*p < 0.05). EBO, extrahepatic biliary obstruction; HCV‐LC, hepatitis C virus related liver cirrhosis; PBC, primary biliary cirrhosis; TLR, Toll‐like receptor.

Baseline expression of TLRs and cytokine receptors in cultured BEC

RT‐PCR revealed that TLR2–5, MD‐2, MyD88, and IRAK‐1 mRNA was amplified in the two ICC and three HIBEC cultured cell lines without stimulation (fig 4). IL‐4R, IL‐6R, IFNγR, and TNFR2 mRNA was also detected in all cells. TNFR1 was detected in both ICC cell lines, but not in the HIBEC cell lines. IL‐5R was found in none of the cell lines. Therefore, IL‐4, IL‐6, IFNγ, and TNFα were chosen as cytokine stimulators for the studies that followed.

Figure 4 Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction analysis of TLR2–5, MD‐2, MyD88, IRAK‐1, and cytokine receptors in cultured cholangiocarcinoma cells (HuCCT1 and CCKSl) and biliary epithelial cells (HIBEC1–3). TLR2–5, MD‐2, MyD88, and IRAK‐1 mRNA was detected in all cells. IL‐4R, IL‐6R, IFNγR, and TNFR2 were expressed by all cells. TNFR1 was detected in cholangiocarcinoma cells only. None of the cells expressed IL‐5R. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3‐phosphate dehydrogenase; IFNγR, interferon γ receptor; IL‐4/5/6R, interleukin 4/5/6 receptor; TLR, Toll‐like receptor; TNFR, tumour necrosis factor receptor.

Cytokine induced TLRs and MD‐2 expression

We investigated the effect of IL‐4, IL‐6, IFNγ, and TNFα treatment on the expression of TLR2–5 and MD‐2 mRNA in cultured cells. As shown in the representative gel images (fig 5A), treatment with IFNγ upregulated the expression of TLR2–5 in all cells. In addition, TNFα upregulated the expression of TLR2. None of the cell lines showed upregulation of TLRs by IL‐4 or IL‐6. The expression of MD‐2 was not affected by cytokine treatment.

Figure 5 Effects of cytokines on TLR2–5, and MD‐2 mRNA expression. Cultured cholangiocarcinoma cells (HuCCTl and CCKS1) and biliary epithelial cells (HIBEC1–3) were treated with phosphate buffered saline alone or with IL‐4, IL‐6, IFNγ, or TNFα. (A) Representative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR) gel images of (A) HuCCT1 and (B) HIBEC1. Treatment with IFNγ upregulated the expression of all TLRs except for MD‐2. TNF‐α also upregulated TLR2. Real time RT‐PCR analysis of the effects of (C) IFNγ and (D) TNFα on TLR2–5 and MD‐2 mRNA expression. Quantitative analysis revealed that the mean (SD) fold increase in TLR2, TLR3, TLR4, TLR5, and MD‐2 mRNA expression after IFNγ treatment was 3.5 (1.1), 2.3 (0.7), 2.0 (0.6), 2.3 (0.8), and 1.1 (0.7), respectively: these results were significant except for MD‐2. After TNFα treatment, the corresponding figures were 3.9 (1.3), 1.4 (0.2), 1.0 (0.1), 1.1 (0.3), and 1.1 (0.2); the results were significant for TLR2 only. Results are shown as mRNA expression relative to that without cytokine treatment. Bars indicate mean ± SD. *p < 0.05. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3‐phosphate dehydrogenase; IFNγ, interferon γ; interleukin; PBS, phosphate buffered saline; TLR, Toll‐like receptor; TNFR, tumour necrosis factor receptor.

The upregulation of TLR2–5 and MD‐2 mRNA expression after treatment with IFNγ and TNFα was measured quantitatively using real time PCR. In all cultured cells, IFNγ significantly upregulated TLR2–5. The average increase in expression (shown as fold increase relative to unstimulated cells) was 3.5, 2.3, 2.0, and 2.3, respectively (fig 5B). TNFα also significantly upregulated TLR2 approximately fourfold (fig 5B).

Influence of preincubation with IFNγ on NF‐κB activation by LPS and PGN treatment

As shown in fig 6, treatment with IFNγ, PGN, or LPS alone increased NF‐κB activation 1.4, 2.3, and 2.6 fold in HuCCT1 cells and 1.8, 2.8, and 3.3 fold in HIBEC1 cells, respectively, compared with untreated cells. Preincubation with IFNγ followed by LPS treatment increased NF‐κB activation 5.8 fold (HuCCT1) and 6.8 fold (HIBEC1), and IFNγ preincubation followed by PGN treatment increased NF‐κB activation 5.9 fold (HuCCT1) and 11.0 fold (HIBEC1). This increased NF‐κB activation seen after sequential treatment with IFNγ and LPS, or IFNγ and PGN, was higher than that found by simply summing the values, which would be a 4.0 fold and a 5.1 fold increase in HuCCT1 and HIBEC1 cells, respectively, for IFNγ plus LPS, and a 3.7 fold and a 4.6 fold increase in HuCCT1 and HIBEC1 cells, respectively, for IFNγ plus PGN. Therefore, this effect was regarded as synergistic rather than additional.

Figure 6 Effect of IFNγ (interferon γ) on peptidoglycan (PGN) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) induced nuclear factor κB (NF‐κB) activation. HuCCT1 and HIBEC1 cells were exposed to IFNγ, and then PGN or LPS. Results are shown as relative activation of NF‐κB, compared with that without treatment. IFNγ by itself increased NF‐κB activation 1.4 and 1.8 fold in HuCCT1 and HIBEC1 cells, respectively. PGN or LPS alone increased NF‐κB activation 2.3 or 2.6 fold in HuCCT1 cells, and 2.8 and 3.3 fold in HIBEC1 cells, respectively. However, preincubation with IFNγ followed by PGN or LPS increased NF‐κB activation 5.9 and 5.8 fold in HuCCT1 cells and 11.0 and 6.8 fold in HIBEC1 cells, respectively. The increase in NF‐κB activation attributable to IFNγ pretreatment followed by LPS or PGN was synergistic, compared with the responses to IFNγ, LPS, or PGN alone. DNA–NF‐κB binding activity was effectively competed for by the wild‐type consensus oligonucleotide, but not mutated oligonucleotide (data not shown).

Discussion

We found diffuse immunohistochemical staining for TLR2–5, MyD88, and IRAK‐1 in the intrahepatic biliary tree of normal human liver, irrespective of anatomical level. This was confirmed by the detection of the corresponding mRNA species by RT‐PCR in the microdissected bile ducts and untreated cultured BECs. MD‐2 mRNA was also detected in cultured cells. However, the MD‐2 protein could not be analysed, because a suitable antibody is not available. Thus, BECs expressing TLRs and related molecules should be regarded as active participants in biliary innate immunity.

Our recent study showed that cultured murine BECs express TLR2–5 and MD‐2 constitutively, and respond to PAMPs by the activation of NF‐κB and the production of TNFα.5 We found in our present study that cultured human BECs also induce NF‐κB activation in response to stimulation with PGN (a TLR2 ligand) and LPS (a TLR4 ligand). Constitutive expression of intracellular signalling molecules (MyD88 and IRAK‐1) in BECs also supports the hypothesis that the activation of TLRs is followed by the activation of associated intracellular downstream signalling molecules, the activation of NF‐κB, and the production of inflammatory mediators.

T cell derived inflammatory cytokines participate in the regulation of TLR expression in several cell types.17,24,25,26 Our study showed that IFNγ (a T helper type 1 (Th1) cytokine) upregulated the expression of TLR2–5 mRNA in cultured BECs. TNFα also upregulated the expression of TLR2. Interactions between TLRs and Th1 cytokines are involved in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel diseases.16,17 Therefore, it is possible that this is also the case in some biliary diseases, such as PBC, which has a Th1 predominant peribiliary cytokine milieu. However, we found no differences between the expression of TLR in the biliary tree between normal and diseased bile ducts, except for TLR4, suggesting that the upregulation of these molecules is not reflected in protein concentrations in vivo. Interestingly, the bile ducts of pathological livers showed both membranous and cytoplasmic staining for TLR4, suggesting that the expression pattern may reflect the upregulation of TLRs in BECs.27

“Our study showed that the T helper type 1 cytokine interferon γ upregulated TLR2–5 mRNA and accelerated the upregulation of pathogen associated molecular pattern induced NF‐κB activation in biliary epithelial cells”

We examined the effect of cytokines on PAMP induced NF‐κB activation in cultured BECs. This effect may reflect the combined influence of the periductal inflammatory microenvironment and the constituents of the bile on the development and persistence of immune mediated biliary diseases. It was found that the increase in NF‐κB activation by sequential treatment with IFNγ and LPS or IFNγ and PGN was higher than simply summing the effects of IFNγ and LPS alone, or IFNγ and PGN alone, suggesting a synergistic effect. Such synergy in intracellular signalling is a known property of the TLR system.28

Although several bacterial and viral species have been reported to be associated with the pathogenesis of biliary diseases, including PBC and hepatolithiasis,29,30,31,32,33 the exact roles of BEC in the development of these biliary diseases is still unclear. Our study showed that the Th1‐type cytokine IFNγ upregulated TLR2–5 mRNA and accelerated the upregulation of PAMP induced NF‐κB activation in BECs. TNFα, which is also produced by Th1 cells, upregulated TLR2. In situ BECs, which constitute the inflamed bile ducts, are shown to produce TNFα.9 This suggests that a Th1 dominant peribiliary milieu leads to the increased susceptibility to PAMPs and the production of biologically active materials, including cytokines from BECs.2,4,29 Li suggested that well coordinated innate immunity signalling enables human cells and tissues to respond efficiently to various substances.34 However, aberrant regulation of these pathways causes various diseases, such as asthma. Thus, increased susceptibility in BECs caused by a Th1 predominant cytokine milieu may be involved in the pathogenesis of the chronic cholangitis seen in PBC.11,12

Take home messages

Our study provides the first evidence that human intrahepatic bile ducts express Toll‐like receptors (TLRs) 2–5, MyD88, and IRAK‐1, which form a pathogen associated molecular pattern (PAMP) recognition system, thus contributing to biliary innate immunity

Interferon γ (IFNγ) synergistically increased the reactivity of biliary epithelial cells to PAMPs

Thus, innate immunity involving the TLR system may play a role in the pathophysiology of the intrahepatic biliary tree in immune mediated diseases, such as primary biliary cirrhosis

In conclusion, our study has provided the first evidence that human intrahepatic bile ducts express TLR2–5, MyD88, and IRAK‐1, which form a PAMP recognition system, thus contributing to biliary innate immunity. Moreover, IFNγ synergistically increased the reactivity of BECs to PAMPs. These findings imply that innate immunity involving the TLR system plays a role in the pathophysiology of the intrahepatic biliary tree, and may be linked to the development of acquired immunity.

Abbreviations

BEC - biliary epithelial cell

EBO - extrahepatic biliary obstruction

HCV‐LC - hepatitis C virus related liver cirrhosis

ICC - intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma

IFNγ - interferon γ

IFNγR - interferon γ receptor

IL - interleukin

IL‐4/5/6R - interleukin 4/5/6 receptor

LPS - lipopolysaccharide

NF‐κB - nuclear factor κB

PAMP - pathogen associated molecular pattern

PBC - primary biliary cirrhosis

PCR - polymerase chain reaction

PGN - peptidoglycan

RT - reverse transcription

Th1, T helper type 1

TLR - Toll‐like receptor

TNFα - tumour necrosis factor α

TNFR - tumour necrosis factor receptor

References

- 1.Nakanuma Y, Hoso M, Sanzen T.et al Microstructure and development of the normal and pathologic biliary tract in humans, including blood supply. Microsc Res Tech 199738552–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hiramatsu K, Harada K, Tsuneyama K.et al Amplification and sequence analysis of partial bacterial 16S ribosomal RNA gene in gallbladder bile from patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. J Hepatol 2000339–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Osnes T, Sandstad O, Skar V.et al Lipopolysaccharides and beta‐glucuronidase activity in choledochal bile in relation to choledocholithiasis. Digestion 199758437–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sasatomi K, Noguchi K, Sakisaka S.et al Abnormal accumulation of endotoxin in biliary epithelial cells in primary biliary cirrhosis and primary sclerosing cholangitis. J Hepatol 199829409–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harada K, Ohira S, Isse K.et al Lipopolysaccharide activates nuclear factor‐kappaB through toll‐like receptors and related molecules in cultured biliary epithelial cells. Lab Invest 2003831657–1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chow J C, Young D W, Golenbock D T.et al Toll‐like receptor‐4 mediates lipopolysaccharide‐induced signal transduction. J Biol Chem 199927410689–10692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jiang Q, Akashi S, Miyake K.et al Lipopolysaccharide induces physical proximity between CD14 and toll‐like receptor 4 (TLR4) prior to nuclear translocation of NF‐kappa B. J Immunol 20001653541–3544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaisho T, Akira S. Toll‐like receptors as adjuvant receptors. Biochim Biophys Acta 200215891–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yasoshima M, Kono N, Sugawara H.et al Increased expression of interleukin‐6 and tumor necrosis factor‐alpha in pathologic biliary epithelial cells: in situ and culture study. Lab Invest 19987889–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park J, Gores G J, Patel T. Lipopolysaccharide induces cholangiocyte proliferation via an interleukin‐6‐mediated activation of p44/p42 mitogen‐activated protein kinase. Hepatology 1999291037–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harada K, Van de Water J, Leung P S.et al In situ nucleic acid hybridization of cytokines in primary biliary cirrhosis: predominance of the Th1 subset. Hepatology 199725791–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dienes H P, Lohse A W, Gerken G.et al Bile duct epithelia as target cells in primary biliary cirrhosis and primary sclerosing cholangitis. Virchows Arch 1997431119–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson K V. Toll signaling pathways in the innate immune response. Curr Opin Immunol 20001213–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akashi S, Saitoh S, Wakabayashi Y.et al Lipopolysaccharide interaction with cell surface Toll‐like receptor 4‐MD‐2: higher affinity than that with MD‐2 or CD14. J Exp Med 20031981035–1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shimazu R, Akashi S, Ogata H.et al MD‐2, a molecule that confers lipopolysaccharide responsiveness on Toll‐like receptor 4. J Exp Med 19991891777–1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abreu M T, Vora P, Faure E.et al Decreased expression of Toll‐like receptor‐4 and MD‐2 correlates with intestinal epithelial cell protection against dysregulated proinflammatory gene expression in response to bacterial lipopolysaccharide. J Immunol 20011671609–1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abreu M T, Arnold E T, Thomas L S.et al TLR4 and MD‐2 expression is regulated by immune‐mediated signals in human intestinal epithelial cells. J Biol Chem 200227720431–20437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schilling J D, Mulvey M A, Vincent C D.et al Bacterial invasion augments epithelial cytokine responses to Escherichia coli through a lipopolysaccharide‐dependent mechanism. J Immunol 20011661148–1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saito K, Minato H, Kono N.et al Establishment of the human cholangiocellular carcinoma cell line (CCKS1) [in Japanese]. Kanzo 199334122–129. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sugawara H, Yasoshima M, Katayanagi K.et al Relationship between interleukin‐6 and proliferation and differentiation in cholangiocarcinoma. Histopathology 199833145–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miyagiwa M, Ichida T, Tokiwa T.et al A new human cholangiocellular carcinoma cell line (HuCC‐T1) producing carbohydrate antigen 19/9 in serum‐free medium. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol 198925503–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kamihira T, Shimoda S, Harada K.et al Distinct costimulation dependent and independent autoreactive T‐cell clones in primary biliary cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 20031251379–1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Renard P, Ernest I, Houbion A.et al Development of a sensitive multi‐well colorimetric assay for active NFkappaB. Nucleic Acids Res 200129E21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu S, Salyapongse A N, Geller D A.et al Hepatocyte toll‐like receptor 2 expression in vivo and in vitro: role of cytokines in induction of rat TLR2 gene expression by lipopolysaccharide. Shock 200014361–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matsumura T, Ito A, Takii T.et al Endotoxin and cytokine regulation of toll‐like receptor (TLR) 2 and TLR4 gene expression in murine liver and hepatocytes. J Interferon Cytokine Res 200020915–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Faure E, Thomas L, Xu H.et al Bacterial lipopolysaccharide and IFN‐gamma induce Toll‐like receptor 2 and Toll‐like receptor 4 expression in human endothelial cells: role of NF‐kappa B activation. J Immunol 20011662018–2024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nagai Y, Akashi S, Nagafuku M.et al Essential role of MD‐2 in LPS responsiveness and TLR4 distribution. Nat Immunol 20023667–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahonen C L, Doxsee C L, McGurran S M.et al Combined TLR and CD40 triggering induces potent CD8+ T cell expansion with variable dependence on type I IFN. J Exp Med 2004199775–784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harada K, Tsuneyama K, Sudo Y.et al Molecular identification of bacterial 16S ribosomal RNA gene in liver tissue of primary biliary cirrhosis: is Propionibacterium acnes involved in granuloma formation? Hepatology 200133530–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Selmi C, Balkwill D L, Invernizzi P.et al Patients with primary biliary cirrhosis react against a ubiquitous xenobiotic‐metabolizing bacterium. Hepatology 2003381250–1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harada K, Ozaki S, Kono N.et al Frequent molecular identification of Campylobacter but not Helicobacter genus in bile and biliary epithelium in hepatolithiasis. J Pathol 2001193218–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu L, Shen Z, Guo L.et al Does a betaretrovirus infection trigger primary biliary cirrhosis? Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 20031008454–8459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mason A L, Xu L, Guo L.et al Detection of retroviral antibodies in primary biliary cirrhosis and other idiopathic biliary disorders. Lancet 19983511620–1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li L. Regulation of innate immunity signaling and its connection with human diseases. Curr Drug Targets Inflamm Allergy 2004381–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]