Abstract

Background

This article presents the results and observed effects of the UK National Health Service Breast Screening Programme (NHSBSP) external quality assurance scheme in breast histopathology.

Aims/Methods

The major objectives were to monitor and improve the consistency of diagnoses made by pathologists and the quality of prognostic information in pathology reports. The scheme is based on a twice yearly circulation of 12 cases to over 600 registered participants. The level of agreement was generally measured using κ statistics.

Results

Four main situations were encountered with respect to diagnostic consistency, namely: (1) where consistency is naturally very high—this included diagnosing in situ and invasive carcinomas (and certain distinctive subtypes) and uncomplicated benign lesions; (2) where the level of consistency was low but could be improved by making guidelines more detailed and explicit—this included histological grading; (3) where consistency could be improved but only by changing the system of classification—this included classification of ductal carcinoma in situ; and (4) where no improvement in consistency could be achieved—this included diagnosing atypical hyperplasia and reporting vascular invasion. Size measurements were more consistent for invasive than in situ carcinomas. Even in cases where there is a high level of agreement on tumour size, a few widely outlying measurements were encountered, for which no explanation is readily forthcoming.

Conclusions

These results broadly confirm the robustness of the systems of breast disease diagnosis and classification adopted by the NHSBSP, and also identify areas where improvement or new approaches are required.

Keywords: breast, external quality assurance, histopathology, pathology, quality assurance

Reduction in mortality from breast cancer by mammographic screening requires that all professional groups involved perform to the highest standards. Although the mode of screening is radiological, the quality of pathological services is of the utmost importance. It is almost always the pathologist who makes the definitive diagnosis of breast cancer and this is made more difficult by the detection of a disproportionate number of borderline lesions in mammographic screening programmes. Furthermore, it is not sufficient for pathologists simply to make accurate diagnoses of malignancy. Additional features of in situ and invasive carcinomas that have prognostic relevance are also required to decide on the most appropriate management for individual patients and to determine the likely success of screening programmes.

“It is almost always the pathologist who makes the definitive diagnosis of breast cancer and this is made more difficult by the detection of a disproportionate number of borderline lesions in mammographic screening programmes”

Two of the major objectives for pathology external quality assurance (EQA) in the National Health Service Breast Screening Programme (NHSBSP) were to improve the consistency of diagnoses made by pathologists and the quality of prognostic information in pathology reports. To achieve these objectives, a standardised reporting proforma was developed, which ensured that all pathologists involved in screening reported the same data using the same terminology. Criteria for making diagnoses and reporting prognostic features were defined in guidelines.1,2 These guidelines can be downloaded from the UK NHS Cancer Screening Programme's website (http://www.cancerscreening.nhs.uk/breastscreen/publications/index.html#p‐qag). The NHSBSP EQA scheme was set up primarily to investigate the level of consistency that pathologists involved in the screening programme could achieve in reporting breast lesions.3 Clearly, this is determined not only by the performance of the pathologists themselves but also by the methodology that they use. Problems identified could be addressed through various initiatives, the success of which could be evaluated in further rounds of the scheme. Subsequently, the scheme was opened to non‐screening pathologists and has been adapted for assessing individual and collective performance.

The aims of our present report were to summarise the findings of the scheme after the first 10 years and to assess the impact it has had on pathological reporting in the UK national screening programme.

Materials and methods

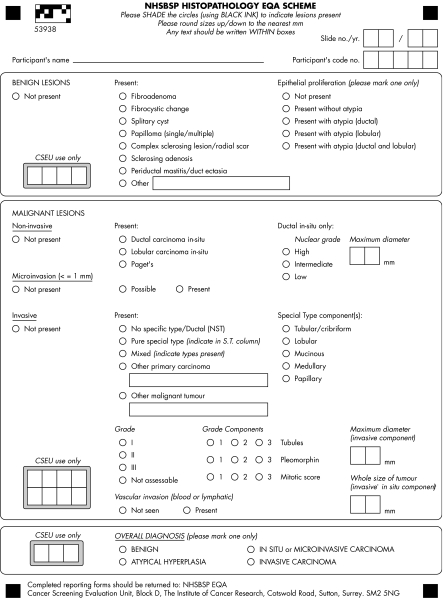

The scheme was piloted among the members (approximately 25) of the national coordinating group for breast screening pathology. The first national circulation was conducted in the second half of 1990 (circulation 902) by sending three sets of consecutive haematoxylin and eosin stained histological sections prepared from single blocks of 12 cases to 17 regional coordinators (Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland, and 14 English health regions) for circulation among pathologists in their regions.1 The slides were checked at the coordinating centre to ensure that they showed identical histological features. The coordinating centre retained the first and last levels for future reference, particularly for cases where unexpectedly high levels of disagreement were encountered. Consequently, 53 sections were prepared from each block. Two hundred and twenty pathologists took part in circulation 902, but the number rose steadily to a maximum of 466 participants by circulation 002. All participants reported the sections using a standard proforma derived from the national reporting form. The EQA scheme proforma changed in line with the revision of the national guidelines in 1995 and requested diagnosis and disease classification where appropriate (fig 1). The latter mainly relates to breast cancer classification and requires the minimum data set information as recognised by the NHSBSP2 and Royal College of Pathologists (http://www.rcpath.org/index.asp?PageID = 254). Completed forms were returned to the cancer screening evaluation unit for analysis. The standard operating procedures for the scheme have been published and can be downloaded from the UK NHS Cancer Screening Programme's website (http://www.cancerscreening.nhs.uk/breastscreen/publications/index.html#p‐qag).

Figure 1 A standard reporting form is used for each case. The form requests a diagnosis classification and for breast cancer cases the minimum standard data set information as required by the UK National Health Service Breast Screening Programme and by the Royal College of Pathologists.

In reporting the slides, participants were expected to follow the guidelines of the NHSBSP, the first edition of which was produced in 1989 and the second in 1995. The second edition took into account, among other things, the findings from the first five years of the EQA scheme. The major revisions were on diagnosing atypical ductal hyperplasia, classifying ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), and grading invasive carcinomas.

The level of agreement was generally measured using κ statistics, which take into account the level of agreement expected purely as a result of chance, and which also require no knowledge of the true diagnosis. For two way classifications there is only a single value of κ, but for consistency of presentation this is given in all columns of the tables in this article. For the three way classifications, an overall κ value was calculated from the κ values for individual categories, weighted by the proportion of reports in each category. Values of κ range from 0 for chance agreement only to +1 for perfect agreement, with a negative value implying systematic disagreement. Landis and Koch4 suggest the following interpretation of different ranges of κ: 0–0.20, slight; 0.21–0.40, fair; 0.41–0.60, moderate; 0.61–0.80, substantial; and 0.81–1.00, almost perfect agreement. One disadvantage of κ statistics is their dependence on the prevalence of cases in each category; in particular, this will influence comparisons between different circulations. The values are presented for groups of three circulations, to minimise differences caused by case selection. However, if there is no case with a majority diagnosis for a particular category within a group of circulations then the expected level of agreement will be high and the κ statistic will be low.5

Categories of cases were selected but there was no selection within these categories by ease or difficulty of diagnosis, typicality of appearance, or other criteria. However, cases were eliminated if section quality was too poor to interpret the histological appearances adequately.

For the purposes of the analysis, microinvasive and in situ carcinomas were grouped together, with microinvasive carcinomas being defined as an in situ carcinoma with one or more foci of invasion, none exceeding 1 mm in maximal dimension.

Results

Major diagnostic categories

Table 1 shows the κ statistics for the major diagnostic categories. According to Landis and Koch's criteria,4 the level of agreement for diagnosing invasive carcinoma was in the almost perfect range. Benign not otherwise specified cases almost fell into this range. However, the level of consistency in this group was influenced by case mix. Although the majority diagnosis was atypical hyperplasia in only five cases, more cases with atypical features were selected than would normally be expected in routine practice. Furthermore, the first six circulations included a disproportionate number of radial scars as part of a special study. The level of agreement in diagnosing in situ or microinvasive carcinoma was in the substantial range, but was almost perfect in two groups of circulations. The level of consistency has been similar throughout the period of the scheme, although there is evidence of some improvement, particularly over the first three years. In contrast, the level of consistency of diagnosing atypical hyperplasia has remained unacceptably low throughout the whole period of the EQA scheme, despite major revision of the diagnostic criteria in the 1995 edition of the guidelines and greater explicitness in how they should be applied.

Table 1 Kappa values for overall diagnosis (all participants).

| Benign | Atypical hyperplasia | In situ/ microinvasive | Invasive | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of cases* | 60 | 5 | 62 | 125 | 252 |

| Circulation† | |||||

| 902, 911, 912 | 0.72 | 0.19 | 0.71 | 0.81 | 0.68 |

| 921, 922, 931 | 0.75 | 0.16 | 0.71 | 0.86 | 0.72 |

| 932, 941, 942 | 0.81 | 0.15 | 0.74 | 0.88 | 0.77 |

| 951, 952, 961 | 0.75 | 0.17 | 0.77 | 0.86 | 0.77 |

| 962, 971, 972 | 0.79 | 0.26 | 0.81 | 0.91 | 0.82 |

| 981, 982, 991 | 0.84 | 0.13 | 0.69 | 0.90 | 0.79 |

| 992, 001, 002 | 0.76 | 0.14 | 0.83 | 0.87 | 0.80 |

| All | 0.79 | 0.18 | 0.76 | 0.88 | 0.78 |

*Number of cases where the diagnosis was made by most members of the national coordinating group; †the first 2 digits of each number refer to the year and the 3rd to the circulation number for that year.

Prognostic features of invasive carcinoma

Subtype

Table 2 summarises the findings. There was a striking improvement in κ values when circulations 902–931 were compared with the remainder, as a result of case selection. In the first six rounds, cases were selected at random from those submitted for inclusion with an original diagnosis of a specific subtype. The levels of agreement for diagnosing mucinous and lobular carcinomas were in the almost perfect and substantial ranges, respectively. The remainder was in the moderate range, with the exception of the mixed type, where the level of agreement was very low. In only three cases was this diagnosis made by the majority, although a mixed appearance was reported for nearly all of the cases.

Table 2 Kappa values for subtype of invasive carcinoma (all participants).

| NST‡ | Lobular | Tubular | Medullary | Mucinous | Mixed | Other | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of cases* | 76 | 15 | 12 | 5 | 10 | 3 | 4 | 125 |

| Circulation† | ||||||||

| 902, 911, 912 | 0.18 | 0.09 | 0.24 | – | – | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.15 |

| 921, 922, 931 | 0.22 | 0.26 | 0.36 | 0.30 | – | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.22 |

| 932, 941, 942 | 0.50 | 0.68 | 0.68 | 0.49 | 0.98 | 0.02 | 0.15 | 0.60 |

| 951, 952, 961 | 0.53 | 0.65 | 0.64 | 0.50 | 0.79 | 0.19 | 0.82 | 0.58 |

| 962, 971, 972 | 0.64 | 0.81 | 0.71 | 0.54 | 0.99 | 0.04 | 0.16 | 0.68 |

| 981, 982, 991 | 0.43 | 0.74 | 0.30 | 0.31 | 0.59 | 0.09 | 0.80 | 0.49 |

| 992, 001, 002 | 0.61 | 0.90 | 0.48 | 0.76 | 0.94 | 0.28 | 0.72 | 0.66 |

| All | 0.52 | 0.75 | 0.54 | 0.54 | 0.90 | 0.14 | 0.60 | 0.58 |

*Number of cases where the diagnosis was made by most members of the national coordinating group; †the first 2 digits of each number refer to the year and the 3rd to the circulation number for that year; ‡NST preferred term for tumours of no special type previously classified as “ductal”.

Grade

Table 3 summarises the findings. Overall, grading was performed with a moderate level of consistency. Two other points are worthy of note. First, grade 2 was always associated with the lowest level of consistency. Second, a significant and sustained improvement in grading consistency was noted from circulation 951 onwards, coinciding with the publication of the revised guidelines.

Table 3 Kappa values for histological grade of NST* cases of invasive carcinoma (all participants).

| 1 | 2 | 3 | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of cases† | 24 | 35 | 17 | 76 |

| Circulation‡ | ||||

| 902, 911, 912 | 0.36 | 0.19 | 0.10 | 0.24 |

| 921, 922, 931 | 0.29 | 0.14 | 0.29 | 0.23 |

| 932, 941, 942 | 0.47 | 0.24 | 0.43 | 0.36 |

| 951, 952, 961 | 0.58 | 0.26 | 0.71 | 0.53 |

| 962, 971, 972 | 0.48 | 0.32 | 0.72 | 0.51 |

| 981, 982, 991 | 0.46 | 0.32 | 0.76 | 0.51 |

| 992, 001, 002 | 0.45 | 0.36 | 0.63 | 0.45 |

| All | 0.46 | 0.31 | 0.66 | 0.47 |

*NST preferred term for tumours of no special type previously classified as “ductal”; †number of cases where the diagnosis was made by most members of the national coordinating group; ‡the first 2 digits of each number refer to the year and the 3rd to the circulation number for that year.

Vascular invasion

Table 4 summarises the findings. Overall, vascular invasion was reported with only a fair level of consistency and showed no tendency to improve over the course of the scheme.

Table 4 Kappa statistics for vascular invasion.

| Overall | ||

|---|---|---|

| No. of cases* | Yes, 10 | No, 115 |

| Circulation† | ||

| 902, 911, 912 | 0.30 | |

| 921, 922, 931 | 0.12 | |

| 932, 941, 942 | 0.41 | |

| 951, 952, 961 | 0.55 | |

| 962, 971, 972 | 0.14 | |

| 981, 982, 991 | 0.18 | |

| 992, 001, 002 | 0.29 | |

| All | 0.30 | |

Only two categories were used, Yes and No, so κ values are the same for each category and the same as overall.

*Number of cases where the diagnosis was made by most members of the national coordinating group; †the first 2 digits of each number refer to the year and the 3rd to the circulation number for that year.

Tumour size

For each case, we calculated the percentage of measurements within ± 3 mm of the median. The distribution of these values in 10% bands and the mean of the values are shown for different sets of cases. For example, the percentages of readings within ± 3 mm of the median of the five medullary cases were 84.4, 94.7, 97.1, 97.1, and 98.5, so one fell between 80% and 89.9% and four fell between 90% and 99.9%; the median of these four values is 97.1%. We found an association between tumour type and the consistency of measuring size (table 5).

Table 5 Consistency of measuring maximum diameter of invasive carcinoma.

| Tumour type | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ductal | Subset of ductal* | Lobular | Tubular | Medullary | Mucinous | |

| % Readings within ±3 mm of median for each case | ||||||

| 50–59 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | ||

| 60–69 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 70–79 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 80–89 | 12 | 9 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 90–99 | 52 | 50 | 7 | 10 | 4 | 6 |

| Total no. of cases | 76 | 65 | 15 | 12 | 5 | 10 |

| Median % of readings | 94.9 | 95.5 | 89.6 | 96.0 | 97.1 | 93.4 |

Values are based on the majority diagnoses of coordinators.

*Excluded cases where ⩾33% of readers did not enter a size, suggesting that it was difficult to measure (6 cases), or the distribution of the sizes was bimodal.

At circulation 952, a “whole size of tumour” measurement was introduced to include any DCIS extending for more than 1 mm beyond the invasive component. This was recorded in addition to the size of the invasive component alone to enable easy identification of carcinomas with an extensive intraduct component, which has been reported in some series to be associated with an increased risk of local recurrence.6,7 Table 6 shows the effect of introducing this additional measurement on the assessment of the invasive size component alone for ductal cases. No improvement was seen.

Table 6 Consistency of measuring invasive carcinoma of NST cases when whole tumour measurements are also taken into account.

| Circulation* | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 902 | 921 | 932 | 951 | 962 | 981 | 992 | |

| Percentage of readings falling within ± 3 mm of median for each case | |||||||

| 50–59 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 60–69 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||

| 70–79 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 80–89 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | |

| 90–99 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 6 | 7 | 10 | 8 |

| Total no. of cases | 8 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 14 | 10 |

| Median of percentage of readings | 92.7 | 92.5 | 93.6 | 90.6 | 94.5 | 96.9 | 97.1 |

The values are the number of cases.

*The first 2 digits of each number refer to the year and the 3rd to the circulation number for that year.

In situ carcinoma

The majority diagnosis was lobular carcinoma in situ in four cases and DCIS in the remainder. The κ statistic for distinguishing lobular carcinoma in situ from DCIS was 0.59.

Classification of DCIS by growth pattern

Table 7 summarises the findings. Cases were classified by dominant growth pattern. Those lesions where participants recorded more than one pattern were classified as mixed. Growth pattern was the sole method of classification up to circulation 951, when it was superseded by nuclear grade in the guidelines. However, the option of using both methods was retained for the EQA scheme. Recording of growth pattern was discontinued at circulation 001. The highest value was obtained for the variant with a comedo growth pattern, with an overall κ statistic of 0.45. The overall κ statistic was unacceptably low and showed no tendency to improve over the course of our study.

Table 7 Classification of ductal carcinoma in situ by growth pattern.

| Comedo | Cribriform | Papillary* | Solid | Mixed | Other | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of cases† | 19 | 9 | 5 | 5 | 13 | 1 | 52 |

| Circulation‡ | |||||||

| 902, 911, 912 | 0.43 | 0.33 | 0.07 | 0.40 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.28 |

| 921, 922, 931 | 0.43 | 0.24 | 0.31 | 0.26 | 0.05 | 0.15 | 0.25 |

| 932, 941, 942 | 0.49 | 0.30 | 0.17 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.27 |

| 951, 952, 961 | 0.48 | 0.35 | 0.27 | 0.41 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.30 |

| 962, 971, 972 | 0.33 | 0.12 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.21 |

| 981, 982, 991, 992 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.42 | 0.20 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.15 |

| All | 0.45 | 0.25 | 0.36 | 0.29 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.28 |

*Includes micropapillary; †based on the majority opinion of the coordinators, except for 2 cases where the majority opinion of all readers was used; ‡the first 2 digits of each number refer to the year and the 3rd to the circulation number for that year.

Classification of DCIS by nuclear grade

Classification by nuclear grade was introduced for the second circulation of 1995. Overall κ for all circulations was only marginally better than that for growth pattern. Table 8 shows that the lowest κ statistics were invariably obtained for the intermediate category. The guidelines recommend classifying DCIS into only two categories: high nuclear grade and other. Using this system would give the same values for κ as listed under “High” (0.51 overall).

Table 8 Kappa statistics for classification of ductal carcinoma in situ by nuclear grade.

| Circulation* | High | Intermediate | Low | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of cases† | 11 | 13 | 4 | 28 |

| Circulation | ||||

| 952, 961 | 0.47 | 0.19 | 0.41 | 0.35 |

| 962, 971, 972 | 0.34 | 0.25 | 0.09 | 0.28 |

| 981, 982, 991 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.19 | 0.11 |

| 992, 001, 002 | 0.64 | 0.29 | 0.30 | 0.44 |

| All | 0.51 | 0.23 | 0.31 | 0.36 |

*The first 2 digits of each number refer to the year and the 3rd to the circulation number for that year; †number of cases where the diagnosis was made by most members of the national coordinating group.

Measuring size of DCIS

Consistency of measuring DCIS was assessed by determining the percentage of cases falling within 3 mm of the median, as for invasive carcinoma. Table 9 summarises the findings and shows that DCIS is measured with less consistency than invasive carcinoma.

Table 9 Measuring size of ductal carcinoma in situ.

| N | |

|---|---|

| Percentage ±3 mm of median | |

| 20–29 | 2 |

| 30–39 | 1 |

| 40–49 | 2 |

| 50–59 | 3 |

| 60–69 | 5 |

| 70–79 | 9 |

| 80–89 | 17 |

| 90–99 | 19 |

| Mean | 79.2 |

| Total no. cases | 58 |

Consistency in diagnosis by category of pathologists

Table 10 compares the overall κ statistics achieved by members of the national coordinating group with those of all the other participants. Not surprisingly, the coordinators consistently showed less interobserver variation, although the difference has shown a steady tendency to narrow over the years.

Table 10 Comparison of overall κ statistics achieved by coordinators and non‐coordinators.

| Circulation | Coordinators | Non‐coordinators | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| κ | Average no. | κ | Average no. | |

| 902, 911, 912 | 0.78 | 21 | 0.67 | 209 |

| 921, 922, 931 | 0.79 | 22 | 0.71 | 248 |

| 932, 941, 942 | 0.83 | 21 | 0.77 | 266 |

| 951, 952, 961 | 0.82 | 22 | 0.77 | 305 |

| 962, 971, 972 | 0.86 | 22 | 0.81 | 381 |

| 981, 982, 991 | 0.82 | 24 | 0.78 | 424 |

| 992, 001, 002 | 0.84 | 22 | 0.80 | 434 |

| All | 0.83 | 22 | 0.77 | 324 |

A similar level of consistency was found, regardless of whether or not pathologists were involved in reporting specimens from the screening programme (table 11).

Table 11 Relation between consistency and involvement in the NHSBSP.

| Circulation | Screening pathologists* | Non‐screening pathologists† | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| κ | Average no. | κ | Average no. | |

| 902, 911, 912 | 0.68 | 198 | 0.57 | 11 |

| 921, 922, 931 | 0.71 | 233 | 0.71 | 15 |

| 932, 941, 942 | 0.77 | 241 | 0.73 | 25 |

| 951, 952, 961 | 0.76 | 268 | 0.77 | 37 |

| 962, 971, 972 | 0.82 | 326 | 0.79 | 55 |

| 981, 982, 991 | 0.79 | 359 | 0.78 | 65 |

| 992, 001, 002 | 0.80 | 368 | 0.79 | 66 |

| All | 0.78 | 285 | 0.77 | 39 |

*Screening readers excludes coordinators; †there may be some non‐screening pathologists in the screening category because of incomplete information.

NHSBSP, National Health Service Breast Screening Programme.

The level of consistency was greater for previous participants than for new participants (table 12). It subsequently increased slightly with the number of times that the participants had taken part.

Table 12 Comparison of consistency achieved by new and previous participants.

| Circulation | New participants | Previous participants | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | κ | N | κ | |

| 902 | 186 | 0.61 | 18 | 0.64 |

| 911 | 66 | 0.59 | 147 | 0.66 |

| 912 | 41 | 0.68 | 182 | 0.77 |

| 921 | 34 | 0.72 | 215 | 0.74 |

| 922 | 15 | 0.73 | 233 | 0.76 |

| 931 | 16 | 0.53 | 245 | 0.65 |

Discussion

Since its inception in 1990, the NHSBSP pathology EQA scheme has played a major role in monitoring the ability of large numbers of UK pathologists, both individually and collectively, to diagnose and classify breast diseases. Only the latter is dealt with here. The scheme has also been able to determine the robustness of the systems of diagnosis and classification adopted by the NHSBSP so that new approaches can be taken where necessary. Such approaches include education and training, improvement of guidelines, and changing diagnostic criteria and classifications systems.

Four main situations were encountered with respect to diagnostic consistency. The first was where consistency is naturally very high; this included diagnosing in situ and invasive carcinoma (and certain distinctive subtypes) and uncomplicated benign lesions. The second was where the level of consistency was unacceptable but could be improved by making the guidelines more detailed and explicit. Only histological grading fell into this category. The third was where consistency could be improved, but only by changing the system of classification—for example, DCIS. The fourth was where no improvement in consistency could be achieved and included diagnosing atypical hyperplasia and reporting vascular invasion. Diagnosing atypical hyperplasia has remained refractory to a major initiative involving significant refinement of diagnostic criteria and much greater explicitness of guidance. No specific measures have yet been taken to improve the reporting of vascular invasion.

“An investigation into methods of improving consistency of identifying vascular invasion would be justified because it has been shown to have prognostic relevance in almost all studies where it has been investigated”

The κ statistics for the four major diagnostic categories were very similar to those reported for the first six rounds of the EQA scheme,3 and those achieved more recently by the European Commission working group on breast screening pathology (EWGBSP).8 In all three studies, the methods of case selection and analysis were identical, but the composition of the groups of participating pathologists (about 25 from all European Union countries in the case of the European group) and the cases examined were different. The guidance on diagnosing atypical hyperplasia underwent major revision after the first UK study. This change also followed studies by Rosai9 and Schnitt et al.10 Rosai showed that concordance could not be achieved if pathologists used different classification systems. Schnitt et al showed that good levels of concordance could be achieved if pathologists used a standard common method and received training. The criteria of Page and Rogers11 were adopted and described in explicit detail with accompanying tables. Thus, the approach was to regard atypical hyperplasia as a positive diagnosis rather than one of exclusion. Despite these measures, the κ statistic remains intractably low, and it is difficult to see how any improvement can be brought about with presently available methodology. Perhaps molecular pathology may hold the key to reproducible and accurate assessment of cancer risk, as the sequence of molecular changes in precursor lesions are painstakingly assembled. Consideration should also be given to the possibility that the methodology required to run this large EQA scheme precludes valid assessment of conditions such as atypical hyperplasia. These microfocal lesions cannot be comparatively represented in all of the sections—up to 70 in number—required for the traditional slide circulation system used. Novel virtual microscopy slide display systems may offer an alternative methodology that could enable large numbers of participants to assess an identical single preparation in a timely fashion.

The prognostic features of invasive carcinomas were generally reported with adequate consistency, with the exception of vascular invasion. The EWGBSP also encountered a low level of consistency in reporting this feature,8 even though the guidelines are very explicit on how to identify it. Two main factors were identified. First, some of the involved vessels are very small and widely dispersed and consequently difficult to detect. Second, retraction artefact may be very difficult to distinguish from vascular invasion, even by experienced pathologists. Careful examination of sufficient numbers of high quality sections of the tumour periphery seems to be the best solution to the problem. Another possibility is the routine use of immunohistochemistry using endothelial cell markers, although this would add significantly to the time and expense of histological reporting. An investigation into methods of improving consistency of identifying vascular invasion would be justified because it has been shown to have prognostic relevance in almost all studies where it has been investigated.12

There was a significant and sustained improvement in grading after the release of the revised guidelines in 1995. It is impossible to prove cause and effect but no other factor can be identified. The criteria for scoring tubule formation, pleomorphism, and mitoses were refined and included photographic illustrations. A graph enabling mitotic counts to be adjusted for the diameter of the high power field of the microscope was also introduced. Interestingly, there has been no further improvement since this initiative was taken. This seems to support the notion that the level of consistency that can be achieved in making histological diagnoses or reporting histological features is ultimately limited by the methodology used. Education, training, and guidance can improve consistency, but only up to a point, beyond which improvement in methodology is needed.

Subtyping invasive carcinomas was associated with an overall level of consistency in the upper moderate range, although lobular and mucinous carcinomas were recognised with substantial and almost perfect levels of consistency, respectively. The lower consistency of diagnosing medullary carcinomas is somewhat surprising in view of their striking appearance, but is consistent with previous studies.13,14 Although the diagnostic criteria are explicit, they appear to be difficult to apply. The level of consistency in diagnosing tubular carcinomas was somewhat lower than expected, but is probably the result of the difficulty in distinguishing some of them from grade 1 ductal (NST) carcinomas. This distinction is not of major importance when other prognostic features are taken into account. The lowest level of consistency was encountered in diagnosing the mixed types. However, pilot studies using modified criteria for classifying these tumours are showing promising results.15

Take home messages

There were four main situations regarding diagnostic consistency: (1) naturally high consistency (included in situ and invasive carcinoma and benign lesions); (2) unacceptable consistency but could be rectified by improving guidelines (histological grading only); (3) consistency could be improved by changing the classification system (for example, ductal carcinoma in situ); (4) no improvement in consistency could be achieved (included diagnosing atypical hyperplasia and reporting vascular invasion)

Size measurements were more consistent for invasive than in situ carcinomas, probably because of the poorer circumscription of invasive lesions and merging with atypical hyperplasia

Consistency of measuring invasive carcinoma is related to subtype but is generally acceptable

The degree of consistency depends on the pathologist: members of the national coordinating group showed greater consistency than other participants, although the difference lessened with time, probably as a result of the quality assessment scheme

Classifying DCIS by growth pattern continues to give κ statistics similar to those that we reported in the 1994 study.3 The major cause of this inconsistency appears to be intralesional variation.16 An improvement was seen when using nuclear grade, but was only modest when three categories were used. Although some of this inconsistency may reflect difficulties in categorising nuclear features,17 intralesional variation in nuclear grade is a factor that may have been underestimated in the past.16 A further increase in κ value into the lower moderate range was achieved when a two way nuclear grading system was used for analysis. The explanation appears to be the elimination of the intermediate category, which is associated with the lowest level of consistency. Kappa values take account of the number of categories by comparing the level of agreement with that which would be expected by chance. These findings are in accord with those recently reported by the ECWGBSP. In this study, the Van Nuys classification gave the highest κ statistic for three way classifications.17 Further improvements in the consistency of classifying DCIS are needed, but satisfactory levels might be achieved purely through morphological refinements.

Size measurements were more consistent for invasive than in situ carcinomas. Probable explanations are the frequently poorer circumscription of the in situ carcinomas and merging with atypical hyperplasia. Consistency of measuring invasive carcinoma is clearly related to subtype but is generally acceptable, except in poorly delineated tumours and those where multiple foci of invasion are seen. Even in cases where there is a high level of agreement on tumour size, a few widely outlying measurements were encountered, for which no explanation is readily forthcoming.

Finally, the degree of consistency is not surprisingly dependent on the pathologists reporting the cases. Greater consistency was seen for the members of the national coordinating group than for the other participants, although the difference has lessened with time, with other participants showing the greater improvement. That this effect is related to the EQA programme is demonstrated by the greater level of consistency achieved by previous participants than by new participants in the EQA scheme. Pathologists reporting specimens from screened women did not achieve a higher level of consistency, even though screening provides greater challenges in everyday practice.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the late J Sloane for his initiation and major contribution to the scheme and this manuscript, in addition to J Bell, S Bacon, A Grieves, and C Munt for technical, administrative, and statistical support to the scheme in the past.

Abbreviations

DCIS - ductal carcinoma in situ

EQA - external quality assessment

EWGBSP - European Commission working group on breast screening pathology

NHSBSP - National Health Service Breast Screening Programme

Footnotes

The authors of this manuscript are members of the EQA scheme management group of the UK national coordinating committee for breast pathology which is responsible for pathology quality assurance in the UK National Health Service Breast Screening Programme (NHSBSP) and preparation of minimum dataset standards in breast cancer pathology for the Royal College of Pathologists. The committee acts as the steering committee for the UK National Breast Screening Histopathology EQA scheme. The scheme is a member UK NEQAS.

References

- 1.National Co‐ordinating Group for Breast Screening Pathology Pathology reporting in breast screening pathology. 1st ed, 1989. Sheffield: NHSBSP Publications, Number 3,

- 2.National Co‐ordinating Group for Breast Screening Pathology Pathology reporting in breast cancer screening. 2nd ed, 1995. Sheffield: NHS BSP Publications Number 3,

- 3.Sloane J P, Ellman R, Anderson T J.et al Consistency of histopathological reporting of breast lesions detected by screening: findings of the UK national external quality assessment (EQA) scheme. UK national coordinating group for breast screening pathology. Eur J Cancer 199430A1414–1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Landis J R, Koch G G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 197733159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brennan P, Silman A. Statistical methods for assessing observer variability in clinical measures. BMJ 19923041491–1494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schnitt S J, Connolly J L, Harris J R.et al Pathologic predictors of early local recurrence in stage I and II breast cancer treated by primary radiation therapy. Cancer 1984531049–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morrow M, Strom E A, Bassett L W.et al Standard for breast conservation therapy in the management of invasive breast carcinoma. CA Cancer J Clin 200252277–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sloane J P, and European Commission Working Group on Breast Screening Pathology Consistency achieved by 23 European pathologists for 12 countries in diagnosing breast disease and reporting prognostic features of carcinomas. Virchows Arch 19994343–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosai J. Borderline epithelial lesions of the breast. Am J Surg Pathol 199115209–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schnitt S J, Connolly J L, Tavassoli F A.et al Interobserver reproducibility in the diagnosis of ductal proliferative breast lesions using standardised criteria. Am J Surg Pathol 1992161133–1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Page D L, Rogers L W. Combined histologic and cytologic criteria for the diagnosis of mammary atypical ductal hyperplasia. Hum Pathol 1992231095–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pinder S E.et al Pathological prognostic factors in breast cancer. III. Vascular invasion: relationship with recurrence and survival in a large study with long‐term follow‐up. Histopathology 19942441–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pederson I P, Holck S, Schuidt T.et al Inter‐ and intraobserver variation in the histopathological diagnosis of medullary breast carcinoma of the breast, and its prognostic implications. Breast Cancer Res Treat 19891491–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rigaud C, Theobald S, Noel P.et al Medullary carcinoma of the breast. A multicenter study of its diagnostic consistency. Arch Pathol Lab Med 19931171005–1008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anderson T J, Sufi F, Ellis I O.et al Implications of pathologist concordance for breast cancer assessments in mammography screening from age 40 years. Hum Pathol 200233365–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elston C W, Sloane J P, Amendoeira I.et al Causes of inconsistency in diagnosing and classifying intraductal proliferations of the breast. European Commission working group on breast screening pathology. Eur J Cancer 2000361769–1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Badve S, A'Hern R P, Ward A M.et al Prediction of local recurrence of ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast using five histological classifications: a comparative study with long follow‐up. Hum Pathol 199829915–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]