Abstract

Aims

To characterise a specific and sensitive marker of Barrett's metaplasia (BM).

Methods

Cases of normal oesophageal squamous mucosa (11 fresh endoscopic biopsies and 10 formalin fixed, paraffin embedded tissue blocks), BM (11 biopsies and 11 tissue blocks), and normal gastric body mucosa (five biopsies and five tissue blocks) were analysed using reverse transcriptase PCR, Western blotting, and immunohistochemistry for EpCAM, and reverse transcriptase PCR for gpA33.

Results

Strong EpCAM mRNA expression was detected in all the BM cases, in contrast to weak expression in all the normal gastric mucosal samples and no expression in any of the normal oesophageal mucosal samples tested. Strong gpA33 mRNA expression was detected in all the BM cases, in contrast to weak expression in a quarter of the normal gastric mucosal samples and no expression in any of the normal oesophageal mucosal samples tested. Western blotting showed EpCAM protein expression in all the BM cases and in none of the normal gastric or oesophageal mucosal samples tested. Immunohistochemistry showed strong EpCAM protein expression in BM and complete absence of expression in normal oesophageal squamous epithelium. Scattered EpCAM expressing cells were found in the gland bases of normal gastric body mucosa.

Conclusions

EpCAM protein and gpA33 mRNA expressions are specific and sensitive markers of BM.

Keywords: Barrett's metaplasia, diagnostic marker, EpCAM, gpA33

Barrett's metaplasia (BM) can be defined as change of the lower oesophageal mucosa to an intestinal glandular phenotype.1 This phenotype in vivo is characterised histologically by the presence of goblet and/or absorptive intestinal epithelial cells. However, both in vitro studies of BM and morphological studies of the cellular origins of BM require a marker that is not expressed in normal oesophageal or gastric mucosae.

There are few existing sensitive and specific markers of BM. The antibody DAS‐1 shows 95% sensitivity and 100% specificity as a marker of BM2 but is not available commercially. Villin, which belongs to a family of Ca+ regulated actin binding proteins, has been tested as a marker of BM, but appears to have low sensitivity.3

Potential markers of BM with high sensitivity would be expected to be universally expressed in normal intestinal epithelium. Such expression is characteristic of EpCAM and gpA33.

EpCAM is a 40 kDa glycoprotein that has several other names, referring to the different antibodies raised against it, such as 17‐1A, AUA1, ESA, GA733, GZ‐1, MOC31, and KS1/4.4 In the normal adult human, EpCAM is detected at the basolateral cell membrane in a variety of epithelia including pseudostratified respiratory epithelium, renal tubular epithelia, mammary gland epithelia, and simple epithelia of the female genital tract.5,6,7 Spurr and colleagues showed, using the monoclonal antibody AUA1, that the protein is expressed in small and large intestinal epithelia, and not in gastric epithelium, but is expressed in intestinal metaplasia (IM) of the stomach and in gastric carcinomas.5 This was confirmed by subsequent reports,4,8 thus supporting a role for EpCAM as a marker for BM. There has been one published report of EpCAM expression in BM samples;3 however, no indication was given of the sensitivity or specificity of the molecule as a marker of BM.

gpA33 was first discovered through raising monoclonal murine antibodies against the human pancreatic carcinoma derived cell line ASPC1. One antibody (MAb A33) was found to react with a surface cell protein of 43 kDa, thus named gpA33. gpA33 is detected at the basolateral membranes of cells and, apart from weak expression in salivary glands, is found only in the small and large intestinal epithelia in the adult human.9 While this suggests the protein may serve as a marker of BM, no attempts to test this hypothesis have yet been published.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cases

Endoscopic biopsies (normal oesophageal squamous mucosa; n = 11; BM, n = 11; and normal gastric body mucosa, n = 5) were collected prospectively (at the John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford), snap frozen, and stored at −70°C until extraction for protein or mRNA. These diagnoses were confirmed by histological review of matched biopsies by a gastrointestinal pathologist (NW). Formalin fixed, paraffin embedded tissue blocks were retrieved from the archives of the Department of Cellular Pathology, John Radcliffe Hospital (normal oesophageal squamous mucosa, n = 10; BM, n = 11; and normal gastric body mucosa, n = 5). Collection and use of the endoscopic biopsies and tissue blocks had been approved by the Oxfordshire clinical research ethics committee.

Reverse transcriptase PCR

RNA was extracted from thawed endoscopic biopsies using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Crawley, UK). cDNA was synthesised from 2 μg of denatured RNA (65°C for 5 minutes) through incubation at 37°C for 60 minutes with final quantities of 1 μmol/l of oligo dTs, 4 U of Omniscript reverse transcriptase (Qiagen), 10 U of RNAse inhibitor (Ambion, Huntingdon, UK) and 0.5 mmol/l of each dNTP. The primers are given in table 1.

Table 1 Primers.

| Protein | Primers (5′–3′) | Product size (bp) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EpCAM | F | GCGTTCGGGCTTCTGCTTGC | 287 | |||

| R | CCGCTCTCATCGCAGTCAGGA | |||||

| gpA33 | F | CCAATCAAAGGAGGGCTCACC | 400 | |||

| R | TTCTCTTAGCTGCTCTGGTGGC | |||||

| β‐actin | F | ACACCTTCTACAATGAGC | 600 | |||

| R | ACGTCACACTTCATGATG | |||||

For each RT‐PCR, a 25 μl PCR reaction volume was used comprising final quantities/concentrations of 0.2 μmol/l of each primer, 0.5 U of AmpliTaq Gold (Perkin‐Elmer, Cambridge, Cambridgeshire, UK) polymerase, 1.5 mmol/l MgCl2, 200 μmol/l of each dNTP, and 100 ng of cDNA. The cycling conditions were: a denaturation step at 95°C for 10 minutes; 25 (β‐actin), 30 (EpCAM), or 35 (gpA33) cycles at 95°C for 45 seconds, 56°C (β‐actin) or 63°C (EpCAM and gpA33) for 45 seconds, and 72°C for 60 (β‐actin) or 30 (EpCAM and gpA33) seconds; and a final extension step at 72°C for 10 minutes. All PCR products were visualised by electrophoresis and ethidium bromide staining in 2% agarose gels.

Western blotting

Protein lysates were prepared from thawed endoscopic biopsies with RIPA lysis buffer (150 mol/l NaCl, 1% w/v, NP40, 0.5% Na deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 50mmol/l Tris HCl pH 7.5) supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail (Complete Mini tablets; Roche Diagnostics, Lewes, East Sussex, UK). Protein samples (35–50 μg of protein) were denatured, separated on SDS‐PAGE and transferred overnight onto nitrocellulose membrane (Hybond‐P; Amersham, Chalfont St Giles, Bucks, UK) using the Mini‐Protean 3 apparatus (Bio‐Rad, Hemel Hempstead, Herts, UK). After blocking in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) with 5% skimmed milk (Marvel; Premier Brands, Spalding, Lincolnshire, UK) and 0.1% Tween 20 (Sigma, Poole, Dorset, UK), the membranes were incubated with primary antibody (table 2). After three washes of 5 minutes each in PBS with 0.1% Tween 20, the membrane was incubated for 1 hour with a horseradish peroxidase linked secondary rabbit anti‐mouse antibody (Dako, Ely, Cambridgeshire, UK; table 2). After three washes of 5 minutes each in PBS with 0.1% Tween 20, the blotted membranes were visualised by chemoluminescence (ECL+ system; Amersham).

Table 2 Details of primary and corresponding secondary antibodies used for Western blotting.

| Target protein (molecular weight) | Primary antibody type, clone and supplier | Primary antibody dilution, diluent,* and incubation conditions | Secondary antibody dilution | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actin (42 kDa) | Mono, AC‐15, Sigma | 1:2000, 5% milk, 1 h at RT | 1:10000 | |||

| Cytokeratin 4 (59 kDa) | Mono, NCL‐LL002, Novocastra† | 1:400, 5% milk, 1 h at RT | 1:1000 | |||

| EpCAM (40 kDa) | Mono, NCL‐ESA, Novocastra | 1:25, 5% milk, 2 h at RT | 1:1000 | |||

| Villin (97 kDa) | Mono, NCL‐L‐Villin, Novocastra | 1:1000, 5% milk, 1 h at RT | 1:5000 |

Mono, monoclonal; RT, room temperature. *All diluents were based on phosphate‐buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20; †Newcastle‐upon‐Tyne, Tyne and Wear, UK.

Immunohistochemistry

Sections (3 μm thick) were cut from the formalin fixed, paraffin embedded tissue blocks, dewaxed, and rehydrated. Antigen retrieval was carried out using microwaving at full power (in an 800 W microwave oven) for 15 minutes in citrate buffer (pH 6.0; Sigma). The Dako Envision kit for mouse primary antibodies (Dako) was used for EpCAM immunohistochemistry. After 5 minutes incubation with the provided peroxidase block, the slides were incubated at 4°C overnight with a 1:50 dilution of anti‐EpCAM monoclonal antibody (clone AUA‐1; CRUK Research Monoclonal Antibody Service Laboratory, London, UK) diluted in antibody diluent (Dako). The slides were then incubated for 30 minutes in the provided anti‐mouse secondary antibody complex. Finally, slides were stained by incubation in the provided diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride reagent (5 minutes incubation) followed by a haematoxylin counterstain.

RESULTS

RT‐PCRs

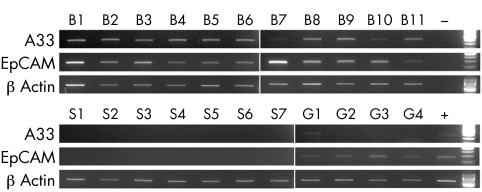

EpCAM mRNA was detected in all 11 BM cases, all 4 normal gastric samples, and none of the 7 normal oesophageal squamous samples studied (fig 1). The gastric samples showed considerably fainter EpCAM RT‐PCR products than did the BM samples (fig 1). All the BM samples and none of the normal oesophageal squamous samples showed gpA33 mRNA by RT‐PCR (fig 1). One of the four gastric samples (G1, see fig 1) showed detectable but weak gpA33 mRNA expression.

Figure 1 gpA33, EpCAM and β‐actin RT‐PCRs performed on mRNA derived from normal oesophageal squamous mucosal samples (S1–7), normal gastric mucosal samples (G1–4) and BM samples (B1–11). Positive (+) and water blank (−) controls and 100 bp ladders are all shown on the right side of the gels.

EpCAM Western blotting

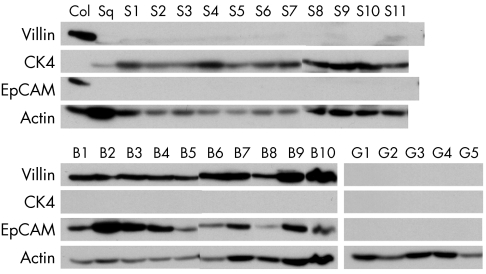

Western blot analysis showed that all the BM cases and none of the normal stomach and oesophageal squamous cases expressed EpCAM protein (fig 2). Expression of EpCAM was always seen in the presence of villin, a recognised marker of intestinal differentiation (fig 2). However, unlike EpCAM, faint villin expression was seen with a few cases of squamous mucosa (for example, S9 and S11 in fig 2).

Figure 2 Villin, cytokeratin 4 (CK4), EpCAM, and β‐actin Western blotting performed on tissue protein lysates prepared from normal oesophageal squamous mucosal samples (S1–11), normal gastric mucosal samples (G1–5), and BM samples (B1–10). The numbers used to label the samples do not necessarily match those used in fig 1. Also shown are normal colonic (Col) and oesophageal squamous (Sq) mucosal lysates used as positive controls for the blotting. CK4 is a marker of (epi)basal squamous cells 10 and thus was not expected to be expressed in either the gastric or BM samples.

EpCAM immunohistochemistry

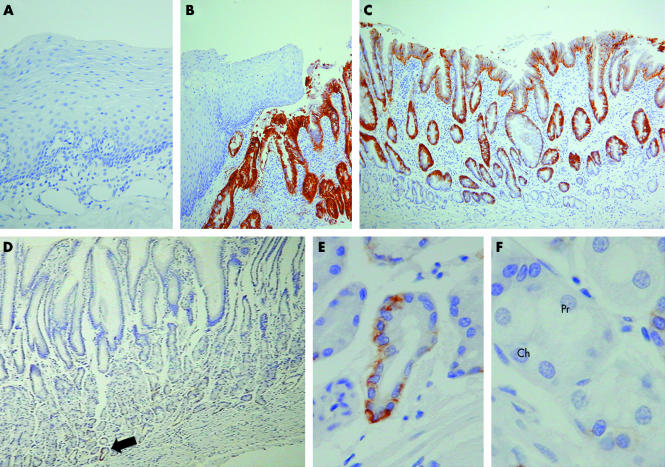

Immunohistochemistry showed lack of EpCAM expression in normal oesophageal squamous epithelium in all 10 cases tested (fig 3). Similarly, EpCAM expression was not seen in any oesophageal gland or oesophageal gland duct epithelium. In contrast, all 11 cases of BM tested showed strong basolateral membranous expression of EpCAM by the metaplastic epithelial cells (both goblet and absorptive cells) (fig 3). Low power examination of AUA1 immunostained normal gastric body mucosa showed no obvious expression of EpCAM. However, on higher power examination, immunostaining was seen in scattered clusters of cells in the gastric gland bases in all five samples analysed (fig 3). These stained cells had the morphological appearance of mucin secreting cells as are found in the gastric foveolar epithelium (fig 3).

Figure 3 EpCAM immunohistochemistry performed on (A) normal oesophageal mucosa, (B–C) Barrett's metaplasia, and (D–F) normal gastric body mucosa. In particular, (B) demonstrates the sharp contrast in EpCAM expression shown by squamous and Barrett's epithelia. (D) Low power examination of gastric mucosa showed no obvious EpCAM immunostaining. (F) However, at higher power, scattered cells at the gland bases (the gland base shown in panel (E) is arrowed in panel (D)) were found to express EpCAM; these labelled cells had the morphological appearance of mucus secreting cells. (F) In contrast, neither chief (Ch) nor parietal (Pr) cells showed any immunostaining for EpCAM.

DISCUSSION

EpCAM protein expression appears to be a sensitive and specific marker of BM. A second but unexpected finding of this study was the occasional cluster of cells expressing EpCAM found at the base of gastric glands. Further characterisation of these cells will require dual labelling studies with, for example, mucin and/or trefoil peptide subtypes. It is unlikely that these cells represent IM, based on morphological grounds and the absence of background inflammation or gland atrophy. The site and morphology of these cells would be consistent with ulcer associated cell lineage/spasmolytic polypeptide expressing metaplastic lineage,11 but presence of this inflammation related epithelium in all five normal gastric body biopsies would be unusual. Regardless of the nature of these EpCAM expressing cells, their inclusion in the gastric biopsies used for RNA extraction may explain the detection of EpCAM mRNA in normal gastric mucosa, though at much lower levels than in BM.

The expression of EpCAM in BM may simply be a “bystander”' marker of intestinal differentiation. Whether EpCAM is an active participant in mediating the metaplastic process is uncertain, particularly as little is known of the normal physiological functions of the protein. In utero, the protein appears to play a role in the differentiation of pancreatic cells.12 Despite its given name, EpCAM seems to have, if anything, a predominantly inhibitory effect on cell to cell adhesion.13 Little is also known of the upstream regulators of EpCAM. Recent reports indicate that inflammatory cytokines such as tumour necrosis factor‐α, interleukin‐4 and interferon‐γ negatively regulate expression of EpCAM.14 Such regulation of EpCAM is unlikely, however, to explain its activation in BM. Indeed, it is the direct opposite of what would be expected if the inflammation of reflux oesophagitis were the direct cause of EpCAM expression during the process of metaplasia.

TAKE HOME MESSAGES

To characterise a specific and sensitive marker of Barrett's metaplasia (BM), analysis was carried out on both fresh biopsy samples and formalin fixed paraffin embedded samples of normal oesophageal squamous mucosa, BM, and normal gastric body mucosa.

EpCAM protein and gpA33 mRNA expression was found in all the BM cases, with only weak or no expression in the normal samples.

EpCAM protein and gpA33 mRNA expressions are specific and sensitive markers of BM.

gpA33 mRNA expression also proved to be a sensitive and specific marker for BM. As with EpCAM, there is only limited knowledge of the functions of gpA33. The restriction of gpA33 expression to basolateral membranes has prompted suggestions that it is involved in cell to cell adhesion between adjacent epithelial cells or between the epithelial cell and intra‐epithelial T lymphocytes.15 In contrast to EpCAM, there is a likely molecular regulator of gpA33 that explains its expression in BM. There are increasing data suggesting that CDX proteins may mediate IM in the gastrointestinal tract.16 CDX1 binds to the putative promoter of A33, and in the developing gut, gpA33 has very similar geographical and temporal patterns of expression to CDX1.17 Johnstone and colleagues also reported absolute correlation in gpA33 and CDX1 mRNA expressions in 10 CRC cell lines.17 We have confirmed this correlation in 33 of a further 34 CRC cell lines studied (unpublished observations). Finally, we have preliminary data showing that CDX1 can induce gpA33 mRNA expression in vitro (unpublished observations). All the above data collectively indicate that CDX1 may be directly driving gpA33 expression in development and diseases of the gastrointestinal tract, including BM.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was funded by Cancer Research UK, CORE (formerly the Digestive Disorders Foundation) and the Jean Shanks Foundation.

Abbreviations

BM - Barrett's metaplasia

IM - intestinal metaplasia

References

- 1.Nandurkar S, Talley N J. Barrett's esophagus: the long and the short of it. Am J Gastroenterol 19999430–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Griffel L H, Amenta P S, Das K M. Use of a novel monoclonal antibody in diagnosis of Barrett's esophagus. Dig Dis Sci 20004540–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kumble S, Omary M B, Fajardo L F.et al Multifocal heterogeneity in villin and Ep‐CAM expression in Barrett's esophagus. Int J Cancer 19966648–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balzar M, Winter M J, de Boer C J.et al The biology of the 17‐1A antigen (Ep‐CAM). J Mol Med . 1999;77699–712. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Spurr N K, Durbin H, Sheer D.et al Characterization and chromosomal assignment of a human cell surface antigen defined by the monoclonal antibody AUAI. Int J Cancer 198638631–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Momburg F, Moldenhauer G, Hammerling G J.et al Immunohistochemical study of the expression of a Mr 34,000 human epithelium‐specific surface glycoprotein in normal and malignant tissues. Cancer Res 1987472883–2891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Litvinov S V, van Driel W, van Rhijn C M.et al Expression of Ep‐CAM in cervical squamous epithelia correlates with an increased proliferation and the disappearance of markers for terminal differentiation. Am J Pathol 1996148865–875. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martin I G, Cutts S G, Birbeck K.et al Expression of the 17‐1A antigen in gastric and gastro‐oesophageal junction adenocarcinomas: a potential immunotherapeutic target? J Clin Pathol 199952701–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sakamoto J, Kojima H, Kato J.et al Organ‐specific expression of the intestinal epithelium‐related antigen A33, a cell surface target for antibody‐based imaging and treatment in gastrointestinal cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 200046(suppl)S27–S32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jankowski J, Hopwood D, Dover R.et al Development and growth of normal, metaplastic and dysplastic oesophageal mucosa: biological markers of neoplasia. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 19935235–246. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmidt P H, Lee J R, Joshi V.et al Identification of a metaplastic cell lineage associated with human gastric adenocarcinoma. Lab Invest 199979639–646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cirulli V, Crisa L, Beattie G M.et al KSA antigen Ep‐CAM mediates cell‐cell adhesion of pancreatic epithelial cells: morphoregulatory roles in pancreatic islet development. J Cell Biol 19981401519–1534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Litvinov S V, Balzar M, Winter M J.et al Epithelial cell adhesion molecule (Ep‐CAM) modulates cell‐cell interactions mediated by classic cadherins. J Cell Biol 19971391337–1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gires O, Eskofier S, Lang S.et al Cloning and characterisation of a 1.1 kb fragment of the carcinoma‐associated epithelial cell adhesion molecule promoter. Anticancer Res 2003233255–3261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heath J K, White S J, Johnstone C N.et al The human A33 antigen is a transmembrane glycoprotein and a novel member of the immunoglobulin superfamily. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 199794469–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guo R J, Suh E R, Lynch J P. The role of cdx proteins in intestinal development and cancer. Cancer Biol Ther 20043593–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnstone C N, White S J, Tebbutt N C.et al Analysis of the regulation of the A33 antigen gene reveals intestine‐specific mechanisms of gene expression. J Biol Chem 200227734531–34539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]