Abstract

Background

Cyclooxygenase‐2 (COX‐2) overexpression is related to poor outcome in several cancers. COX‐2 is upregulated in 42–90% of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas and is a potential target for chemotherapy. Earlier studies have not shown the expression of COX‐2 to be a prognostic factor in pancreatic cancer.

Objective

To evaluate the prognostic value of COX‐2 in a series of patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

Methods

128 patients operated on for pancreatic adenocarcinoma at Helsinki University Central Hospital between 1974 and 1998 provided sections from primary tumours which were immunohistochemically stained with a COX‐2‐antihuman monoclonal antibody.

Results

Cytoplasmic COX‐2 reactivity (>5%) occurred in 46 specimens (36%), correlating neither with age, sex, stage, size, tumour stage, nodal metastases, nor grade. Lack of COX‐2 expression correlated with distant metastases (p = 0.026). In univariate survival analysis, COX‐2 expression (p = 0.0114), stage (p = 0.0002), grade (p = 0.0001), and age (p = 0.042) had prognostic significance. One, two, and five year survival rates were 51%, 32%, and 8% in the COX‐2 negative groups compared with 34%, 5%, and 5% in the COX‐2 positive groups (p = 0.011). Prognostic significance was especially high for patients operated on with curative intent (p = 0.004). In multivariate analysis, COX‐2 was an independent prognostic factor (hazard ratio = 1.6 (95% confidence interval, 1.1 to 2.3)).

Conclusions

Expression of COX‐2 was associated with poor outcome from pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and was independent of tumour stage, grade, or age in multivariate analysis.

Keywords: pancreatic neoplasms, cyclooxygenase‐2, survival, immunohistochemistry

Rudolf Virchow suggested in 1863 that there was a connection between cancer and persistent inflammation.1 In population based studies, the use of non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) protects from colorectal and possibly from other cancers.2,3,4 Cyclooxygenase‐2 (COX‐2) is an integral membrane protein and the rate limiting enzyme in the biosynthesis of such prostanoids as prostaglandins, thromboxanes, and prostacyclins in acute inflammation. In most tissues, COX‐2 is not physiologically expressed. However, hormones, cytokines, growth factors, and tumour promoters rapidly induce COX‐2 expression.5,6 At molecular level, a key role in the process that links inflammation to carcinogenesis seems to be activation of COX‐2, although the intracellular pathways in that process are still mostly unknown.

Increased tissue levels of COX‐2 occur in several human carcinomas. In tumorigenesis, COX‐2 may take part in stimulation of proliferation, in inhibition of apoptosis, and in invasion by enhancing production of matrix metalloproteinases and by promoting angiogenesis.7,8,9 Increased COX‐2 expression is associated with a poor prognosis in oesophageal, gastric, colonic, breast, and ovarian carcinomas.10,11,12,13,14 In the pancreas, COX‐2 is expressed in the cytoplasm of ductal tumour cells but not in the surrounding stroma.15 In pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas, COX‐2 is upregulated in 42% to 90% of cases.15,16,17,18 The association of aspirin use with pancreatic cancer risk has been explored in several epidemiological studies, with controversial results.19 However, several NSAIDs inhibit pancreatic cancer in hamster models.20,21 NSAIDs also inhibit the growth of human pancreatic cancer cell lines.22

Our aim in this study was to investigate COX‐2 expression in a series of cases of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and compare immunohistochemical staining results with clinicopathological factors such as survival, histological grade, TNM stage, tumour size, tumour location, age, and sex.

Methods

Patients

The study involved surgical specimens from 128 consecutive patients undergoing surgery for pancreatic adenocarcinoma at Helsinki University Central Hospital between 1974 and 1998, and with a histological block available in the files of the Department of Pathology. The most representative sample of the primary tumour was chosen, and the diagnosis of pancreatic adenocarcinoma was confirmed from haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and van Gieson stains by a pathologist (SN). The median age of the patients at diagnosis was 62 years (range 34 to 79 ); 72 (56%) were female and 56 (44%) male. Histological grade was re‐evaluated by a pathologist (SN), revealing 14 well differentiated (grade 1), 77 moderately differentiated (grade 2), and 37 poorly differentiated (grade 3) tumours. Staging was done according to the UICC 1997 TNM classification, based on patient records, imaging methods, operation records, and histological evaluation. Patients comprised 25 at stage I, 39 at stage II, 28 at stage III, and 35 at stage IV. All patients underwent surgery, either curative (R0) pancreaticoduodenectomy (n = 85), non‐curative (R1) pancreaticoduodenectomy (n = 33), palliative bypass (n = 6), or diagnostic laparotomy (n = 4). The operation was considered to be R0 pancreaticoduodenectomy when no macroscopic or microscopic residual tumour was present. Median survival for patients who underwent R0 pancreaticoduodenectomy was 15.1 months, for those undergoing R1 pancreaticoduodenectomy 6.7 months, for those undergoing palliative bypass 2.4 months, and for those undergoing diagnostic laparotomy one month; 120 patients died of pancreatic cancer. Six patients were alive at the end of the study, and two died from diseases other than cancer. Survival data for the patients came from the patient records, Statistics Finland, and the Finnish Population Registry.

Staining

Our COX‐2 immunohistochemical staining has been described in detail previously.23 Briefly, archival formalin fixed, paraffin embedded tissue samples were freshly cut (4 µm), and deparaffinised, and microwave treated for antigen retrieval. For immunohistochemical staining, a COX‐2 specific mouse antihuman monoclonal antibody (160112;5 Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA) was used at a dilution of 1:200. Bound antibody was visualised by the avidin‐biotin complex immunoperoxidase technique (Vectastain ABComplex, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, California, USA). For each staining batch we used as a positive control a colon sample in which adenocarcinoma cells stained >50%, and adjacent epithelial non‐neoplastic cells stained 5–10%. As an internal control we used pancreatic islet cells that consistently expressed COX‐2.24 As negative controls we used sections with phosphate buffered saline or non‐immune antibody instead of primary antibody.

Interpretation of immunohistochemistry

Two independent pathologists (SN and AR) interpreted the staining results while unaware of the clinical data. COX‐2 expression was considered negative if fewer than 5% of the tumour cells expressed COX‐2, weak if 5–10% of the cells were positive, moderate if 10–50% of the cells were positive, and strong if more than 50% of the cells were positive. Cells were considered positive only if COX‐2 intensity was moderate (granular cytoplasmic stain) or strong (diffuse +++ staining). Samples with 0–5% of any intensity were considered negative. The six samples given scores by the pathologists that differed by two categories were re‐evaluated, and the consensus score served for further analysis. For dichotomic analysis, we chose 5% as the cut off line for COX‐2 positive tumours.

Statistical analysis

The associations between factors were calculated by the χ2 test and Fisher's exact test in cases of very small expected frequencies. For life tables we used the Kaplan–Meier product limit method. Differences in survival were compared by the log‐rank or log‐rank for trend test when appropriate. Disease specific overall survival was from the date of diagnosis to death from pancreatic cancer, with patients dying of other causes censored. Multivariate survival analysis was with the COX proportional hazards model, entering the following covariates: histological grade, TNM stage, COX‐2 (negative v positive), tumour location (head of pancreas v other), tumour size (⩽2 cm v 2–4 cm v >4 cm), and age (⩽62 v >62 years). Cox regression was done by a backward stepwise selection of variables, and a probability (p) value of 0.05 was adopted as the limit for inclusion of a covariant. Statistical analyses were done using SPSS 11.0.1 software (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Results

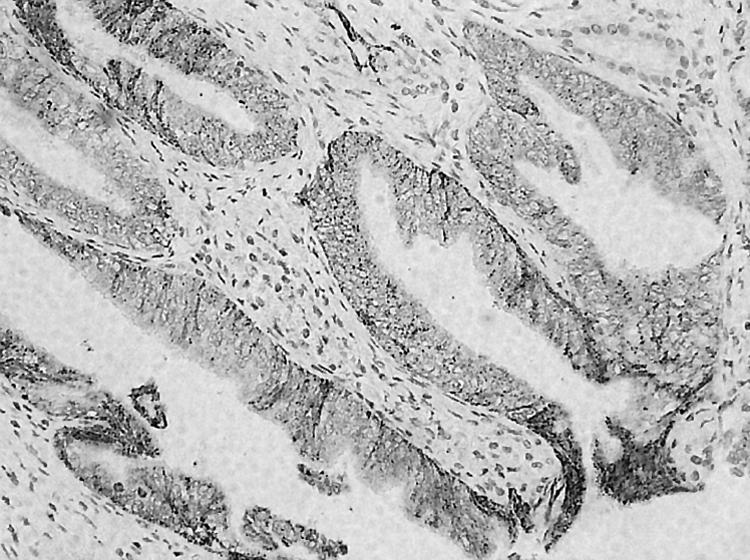

Immunoreactivity of COX‐2 in 128 pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas showed 82 (64%) to be negative, 16 (13%) weakly positive, 27 (21%) moderately positive, and three (2%) strongly positive. COX‐2 expression was evident in cytoplasmic granules of ductal tumour cells, whereas the stroma was negative (fig 1). Islet cells stained positive in all samples, including those with no COX‐2 expression in the tumour.

Figure 1 Immunohistochemical staining of COX‐2 in pancreatic adenocarcinoma, showing a well differentiated ductal carcinoma with strong positivity for COX‐2. The stain is evident in the cytoplasm of the tumour cells, whereas the adjacent stroma is negative. Original magnification ×20.

No correlation appeared between COX‐2 expression and sex, grade, stage, nodal status, tumour size (<2 cm v 2–4 cm v >4 cm), curability, or tumour location (head v other). COX‐2 expression was associated with distant metastases (n = 9); none of the primary tumours with distant metastases (p = 0.026) showed any COX‐2 expression. COX‐2 was expressed more often in samples of older patients (>62 years), although not significantly so (p = 0.0655) (table 1).

Table 1 Distribution of COX‐2 according to preoperative characteristics in 128 patients with pancreatic cancer.

| Clinicopathological variable | n | COX‐2 >5% | χ2 | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n (%)) | ||||

| Age (years) | ||||

| ⩽62 | 64 | 18 (28%) | 3.4 | 0.066 |

| >62 | 64 | 28 (44%) | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 72 | 26 (36%) | 0.002 | 0.096 |

| Male | 56 | 20 (36%) | ||

| Grade | ||||

| 1 | 14 | 4 (28%) | 3.7 | 0.158 |

| 2 | 77 | 24 (31%) | ||

| 3 | 37 | 18 (49%) | ||

| Grades 1 and 2 v 3 | ||||

| 1 and 2 | 91 | 28 (31%) | 3.6 | 0.056 |

| 3 | 37 | 18 (49%) | ||

| Stage | ||||

| I | 25 | 7 (28%) | 4.0 | 0.261 |

| II | 39 | 15 (38%) | ||

| III | 28 | 14 (50%) | ||

| IV | 35 | 10 (29%) | ||

| Unavailable | 1 | – | ||

| Primary tumour (T) | ||||

| 1 | 7 | 1 (14%) | 2.4 | 0.495 |

| 2 | 28 | 9 (32%) | ||

| 3 | 63 | 26 (41%) | ||

| 4 | 29 | 10 (34%) | ||

| Unavailable | 1 | – | ||

| Regional nodes (N) | ||||

| 0 | 78 | 27 (35%) | 8.9 | 0.345 |

| 1 | 39 | 17 (44%) | ||

| Unavailable | 11 | – | ||

| Distant metastasis (M) | ||||

| 0 | 118 | 46 (39%) | 3.9 | 0.026 |

| 1 | 9 | 0 (0) | ||

| Unavailable | 1 | – | ||

| Tumour size | ||||

| ⩽2 cm | 19 | 6 (32%) | 0.3 | 0.864 |

| 2–4 cm | 66 | 25 (38%) | ||

| >4 cm | 29 | 10 (34%) | ||

| Unavailable | 14 | – | ||

| Curability | ||||

| Intent to cure | 85 | 31 (36%) | 0.03 | 0.860 |

| Non‐curative | 43 | 15 (35%) | ||

| Location | ||||

| Head | 113 | 39 (35%) | 1.1 | 0.225 |

| Other location | 13 | 7 (54%) |

COX‐2, cyclooxygenase‐2.

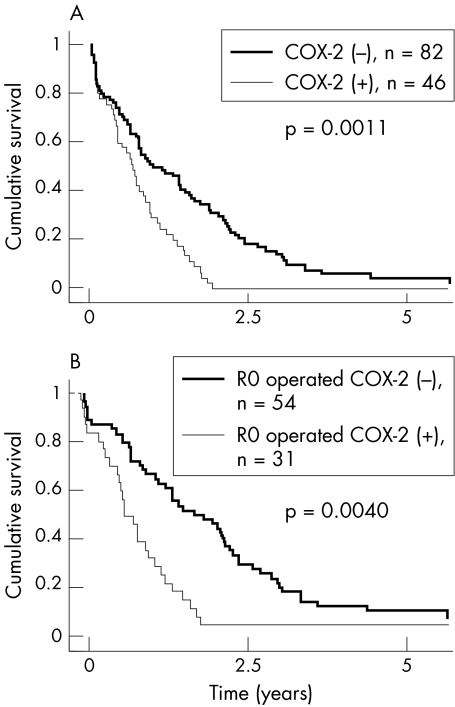

Survival among patients with COX‐2 negative tumours was (p = 0.011) than among those with COX‐2 positive tumours (fig 2, table 2): one, two, and five year survival rates were 34%, 5%, and 5% in COX‐2 positive categories, compared with 51%, 32%, and 8% in the COX‐2 negative category. Median survival for patients with COX‐2 positive tumours was 8.1 months, compared with 13.2 months for COX‐2 negative tumours. Low histological grade, low TNM stage, no distant metastases, and curability showed a strong association with better survival in univariate survival analysis (p<0.001). Young age (p = 0.042), low stage (p = 0.045), small tumour size (p = 0.045), and tumour in head of pancreas (0.045) were also associated with better prognosis (table 2). Within the group of patients undergoing R0 pancreaticoduodenectomy, COX‐2 expression in univariate analysis correlated with survival (p = 0.004). One, two, and five year survival rates were 40%, 7%, and 0% in COX‐2 positive categories, compared with 67%, 46%, and 11% in the COX‐2 negative category. Median survival was 10 months for COX‐2 positive patients, compared with 20 months for patients with COX‐2 negative tumours (fig 2B).

Figure 2 Cumulative survival curves for 128 patients with pancreatic cancer. Survival of those with COX‐2 negative tumours was significantly better than that of patients with COX‐2 positive tumours. This was true in (A) the whole patient group and (B) in patients undergoing R0 pancreaticoduodenectomy (n = 85).

Table 2 Univariate analysis of the relation between preoperative characteristics and survival of 128 patients with pancreatic cancer.

| Clinicopathological variable | n | % | 1 year | 95% CI | 2 year | 95% CI | 5 year | 95% CI | χ2 | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CS (%) | CS (%) | CS (%) | ||||||||

| COX‐2 | ||||||||||

| Negative ⩽5% | 82 | 64 | 51 | 40 to 62 | 32 | 22 to 42 | 8 | 2 to 14 | 3.18 | 0.074 |

| Weak 5 to 10% | 16 | 13 | 14 | 0 to 32 | 7 | 0 to 20 | 7 | 0 to 20 | ||

| Moderate 10 to 50% | 27 | 21 | 44 | 26 to 63 | 0 | 0 to 0 | 0 | 0 to 0 | ||

| Strong >50% | 3 | 2 | 33 | 0 to 88 | 33 | 0 to 88 | 33 | 0 to 88 | ||

| COX‐2 | ||||||||||

| ⩽5% | 82 | 64 | 51 | 40 to 62 | 32 | 22 to 42 | 8 | 2 to 14 | 6.4 | 0.011 |

| >5% | 46 | 36 | 34 | 20 to 47 | 5 | 0 to 11 | 5 | 0 to 11 | ||

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Female | 72 | 56 | 45 | 34 to 57 | 23 | 13 to 32 | 7 | 1 to 13 | 0.12 | 0.727 |

| Male | 56 | 44 | 45 | 32 to 58 | 21 | 11 to 32 | 6 | 0 to 13 | ||

| Age (years) | ||||||||||

| ⩽62 | 64 | 50 | 51 | 39 to 63 | 25 | 15 to 36 | 8 | 1 to 15 | 4.1 | 0.042 |

| >62 | 64 | 50 | 39 | 27 to 51 | 19 | 9 to 28 | 6 | 0 to 12 | ||

| Grade of differentiation | ||||||||||

| 1 | 14 | 11 | 79 | 57 to 100 | 43 | 17 to 67 | 29 | 5 to 52 | 15.0 | <0.001 |

| 2 | 77 | 60 | 48 | 36 to 59 | 25 | 15 to 35 | 7 | 1 to 12 | ||

| 3 | 37 | 29 | 27 | 13 to 41 | 8 | 0 to 17 | 0 | 0 to 0 | ||

| TNM stage | ||||||||||

| I | 25 | 20 | 64 | 45 to 83 | 36 | 17 to 55 | 12 | 0 to 25 | 13.6 | <0.001 |

| II | 39 | 30 | 51 | 36 to 67 | 33 | 19 to 48 | 8 | 0 to 16 | ||

| III | 28 | 22 | 41 | 22 to 60 | 19 | 4 to 33 | 7 | 0 to 17 | ||

| IV | 35 | 27 | 26 | 11 to 40 | 3 | 0 to 8 | 0 | 0 to 0 | ||

| Unavailable | 1 | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| Primary tumour (T) | ||||||||||

| T1 | 7 | 5 | 71 | 38 to 100 | 29 | 0 to 62 | 0 | 0 to 0 | 4.0 | 0.045 |

| T2 | 28 | 22 | 46 | 28 to 65 | 32 | 15 to 49 | 11 | 0 to 22 | ||

| T3 | 63 | 49 | 47 | 35 to 59 | 26 | 15 to 37 | 8 | 1 to 15 | ||

| T4 | 29 | 23 | 31 | 14 to 48 | 3 | 3 to 10 | 3 | 3 to 10 | ||

| TX | 1 | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| Regional nodes (N) | ||||||||||

| N0 | 78 | 61 | 55 | 44 to 66 | 28 | 18 to 38 | 8 | 2 to 14 | 2.5 | 0.115 |

| N1 | 34 | 27 | 34 | 19 to 50 | 16 | 4 to 28 | 8 | 1 to 17 | ||

| NX | 11 | 9 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| Distant metastasis (M) | ||||||||||

| M0 | 118 | 92 | 48 | 39 to 57 | 24 | 16 to 32 | 7 | 3 to 12 | 12.5 | <0.001 |

| M1 | 9 | 7 | 11 | 9 to 32 | 0 | 0 to 0 | 0 | 0 to 0 | ||

| MX | 1 | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| Tumour size | ||||||||||

| ⩽2 cm | 19 | 15 | 67 | 46 to 89 | 23 | 3 to 42 | 0 | 0 to 0 | 3.89 | 0.049 |

| 2 to 4 cm | 66 | 52 | 53 | 41 to 65 | 27 | 17 to 38 | 11 | 4 to 19 | ||

| >4 cm | 29 | 23 | 17 | 4 to 31 | 10 | 1 to 21 | 3 | 0 to 10 | ||

| Unavailable | 14 | 11 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| Tumour location | ||||||||||

| Head | 113 | 88 | 47 | 38 to 57 | 24 | 16 to 32 | 8 | 3 to 13 | 4.01 | 0.045 |

| Other location | 13 | 6 | 31 | 6 to 56 | 8 | 0 to 22 | 0 | 0 to 0 | ||

| Curability | ||||||||||

| Intent to cure | 85 | 66 | 57 | 47 to 68 | 32 | 22 to 42 | 10 | 3 to 16 | 23.11 | <0.001 |

| Non‐curative | 43 | 34 | 21 | 9 to 33 | 2 | 2 to 7 | 0 | 0 to 0 |

CI, confidence interval; COX‐2, cyclooxygenase‐2; CS, cumulative survival.

Table 3 Backward stepwise Cox proportional hazard model figures for 128 patients with pancreatic cancer.

| Covariate | Coefficient | χ2 | p Value | HR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 1 | 12.138 | 0.002 | 1.0 | ||

| Grade 2 | 0.788 | 2.2 | 1.1 to 4.3 | ||

| Grade 3 | 1.246 | 3.5 | 1.7 to 7.1 | ||

| TNM stage 1 | 20.961 | <0.0001 | 1.0 | ||

| TNM stage 2 | 0.188 | 1.2 | 0.7 to 2.0 | ||

| TNM stage 3 | 0.395 | 1.5 | 0.8 to 2.7 | ||

| TNM stage 4 | 1.248 | 3.5 | 1.9 to 6.4 | ||

| COX‐2 | 0.484 | 5.562 | 0.018 | 1.6 | 1.1 to 2.4 |

| Age >62 years | 0.411 | 4.011 | 0.045 | 1.5 | 1.0 to 2.3 |

Tumour location, NS.

CI, confidence interval; COX‐2, cyclooxygenase‐2; HR, hazard ratio.

In multivariate analysis, COX‐2 retained its independent prognostic significance (p = 0.018). TNM stage and histological grade (HR 3.5) were the strongest independent prognostic factors, followed by COX‐2 (HR = 1.6).

Discussion

In this retrospective study of 128 pancreatic adenocarcinoma patients, increased COX‐2 expression was associated with a poor prognosis and was independent of stage and grade (HR = 1.6). COX‐2 thus seems to be a promising prognostic marker, especially for patients undergoing R0 pancreaticoduodenectomy. Patients with COX‐2 expression in their tumours had a strikingly poor prognosis; only two patients survived more than two years, even in the group undergoing surgery for cure. In our earlier studies on other cancer forms, COX‐2 was also associated with poor outcome.10,13,14,23,25

In the present study COX‐2 expression was less (36%) than in most published studies (42% to 90%).15,16,17,18 One reason could be the use of different antibody preparations. For immunohistochemical staining we used a COX‐2 specific mouse antihuman monoclonal antibody. Before choosing this, we tested other antibodies to find the optimal tool, as described in an earlier study.26 To avoid intra‐assay or interassay variability, we used the positive control described in Methods. This also helped us to score the trial specimens. For example Merati et al27 used a polyclonal antibody, and Okami et al28 used polyclonal rabbit antihuman COX‐2 antibodies and had a 74% to 90% positivity rate. Our experience is that in antigenic blocking experiments polyclonal antibodies are more sensitive but do not show as high a specificity as the monoclonal antibody.26 Using this same method we have reported the prognostic significance of COX‐2 in other cancer forms, such as oesophageal, breast, ovarian, and gastric carcinoma (accepted for publication).10,13,14

The difference between our results and others may also depend in part on different cut off values. Our 5% cut off for positivity and only moderate (granular cytoplasmic stain) to strong (diffuse +++ staining) intensity meant that samples with 0 to 5% of any intensity were considered negative.

Three studies on COX‐2 in pancreatic cancer show no significant association between COX‐2 and prognosis.27,28,29 One study on 120 patients showed only a tendency for association within the whole patient group and within a patient group that received chemotherapy.28 One reason for differing results could be differences in patient series. Our patients received no chemoradiation but mostly underwent R0 pancreaticoduodenectomy. We had a more significant correlation between COX‐2 and survival within patients operated on for cure. Another reason why results may differ regarding COX‐2 association with survival may be the antibody used. In two reports including 50 and 72 patients, study power was unassessed.28,29 Had the patient group been larger, results might have been similar to ours.

Many studies report somewhat improved survival rates in recent patient series, probably because of factors such as surgical techniques, postoperative care, and adjuvant protocols. Our patients experienced no major changes in surgical techniques or strategy during follow up. In Helsinki, extended lymphadenectomy was not initiated until 1999. In our series, no patients received neoadjuvant therapy and a few received postoperative chemotherapy. There certainly has been improvement in preoperative and postoperative care, but we find no reason to believe that changes in treatment would have affected COX‐2 figures or our conclusions.

Both the hereditary and sporadic forms of chronic pancreatitis are associated with an increased risk developing pancreatic cancer,30,31,32 which often shows a strong desmoplastic reaction around the tumour.33 These cells produce cytokines, growth factors, and inflammation mediators34 known to induce COX‐2 expression. In chronic pancreatitis, COX‐2 expression is increased in pancreatic acinar and hyperplastic ductal cells. Likewise in pancreatic cancer, the ductal expression of COX‐2 is markedly upregulated.35 It is reasonable to hypothesise that as COX‐2 is inducible and implicated in epithelial tumour development, its expression in pancreatic tumour results in a poor prognosis. Our results are in accordance with this hypothesis, showing the independent prognostic significance of COX‐2 expression. The evidence of pancreatic tumour growth inhibition by COX‐2 inhibitors also supports this hypothesis.

Kokawa et al36 showed that COX‐2 correlated with inhibition of cell growth by aspirin in four pancreatic cancer cell lines and proposed chemoprevention by COX inhibitors. Other groups have demonstrated tumour growth inhibition by selective COX‐2 inhibitors, but this was COX‐2 independent.18,37 In preclinical studies, COX‐2 inhibitors enhance the antitumoral efficacy of gemcitabine.22 Our pancreatic cancer patients received no adjuvant therapy. Earlier studies and the present findings support efforts to initiate clinical trials to discover whether tumours with COX‐2 expression could distinguish those patients who benefit from neoadjuvant treatment combined with surgery.

Take home message

Expression of COX‐2 was associated with a poor outcome in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and was independent of tumour stage, grade, and age in multivariate analysis

Because our study was based on patients operated on for pancreatic cancer, only nine had distant metastases, and interestingly, none of these patients' primary tumour samples expressed COX‐2. This could reflect the small number of patients or the biology of the disease. Pancreatic cancer is known to invade surrounding tissues at an early phase. COX‐2 seems to enhance cell proliferation and the production of matrix metalloproteinases and to promote angiogenesis, facilitating local tumour growth in pancreatic cancer.8,9 At later phases, other factors join the biological process, leading to metastases.

Results for COX‐2 expression and the differentiation of tumour cells in previous studies on pancreatic cancer are inconsistent, with most showing no correlation of grade of pancreatic cancer with COX‐2 expression.28,29,36 In a study by Merati et al,27 increased COX‐2 expression was associated with well differentiated glandular components of the pancreatic tumour. When we reassessed the histological grade of all tumours and compared the results with the COX‐2 expression, COX‐2 failed to correlate with grade.

In conclusion, based on our study of 128 patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma, COX‐2 seems to be an independent prognostic factor. The possibility of including COX‐2 inhibitors in treatment of pancreatic cancer deserves evaluation.

Acknowledgements

The technical assistance of Elina Laitinen, Päivi Peltokangas, and Elina Malkki is greatly appreciated. This study was supported by grants from the Finnish Cancer Society, Finska Läkaresällskapet, Medicinska Understödsföreningen Liv och Hälsa, Helsinki University Central Hospital Research Funds, the Academy of Finland, and the Sigrid Juselius Foundation.

Abbreviations

COX‐2 - cyclooxygenase‐2

HR - hazard ratio

NSAID - non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drug

TNM - tumour stage, node, metastasis classification

UICC - International Union Against Cancer

References

- 1.Balkwill F, Mantovani A. Inflammation and cancer: back to Virchow? Lancet 2001357539–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sørensen H T, Friis S, Nørgård B.et al Risk of cancer in a large cohort of nonaspirin NSAID users: a population‐based study. Br J Cancer 2003881687–1692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meier C R, Schmitz S, Jick H. Association between acetaminophen or nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and risk of developing ovarian, breast, or colon cancer. Pharmacotherapy 200222303–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenberg L, Louik C, Shapiro S. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug use and reduced risk of large bowel carcinoma. Cancer 1998822326–2333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones D A, Carlton D P, McIntyre T M.et al Molecular cloning of human prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase type II and demonstration of expression in response to cytokines. J Biol Chem 19932689049–9054. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamasaki Y, Kitzler J, Hardman R.et al Phorbol ester and epidermal growth factor enhance the expression of two inducible prostaglandin H synthase genes in rat tracheal epithelial cells. Arch Biochem Biophys 1993304226–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DuBois R N, Shao J, Tsujii M.et al G1 delay in cells overexpressing prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase‐2. Cancer Res 199656733–737. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsujii M, Kawano S, DuBois R N. Cyclooxygenase‐2 expression in human colon cancer cells increases metastatic potential. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1997943336–3340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsujii M, Kawano S, Tsuji S.et al Cyclooxygenase regulates angiogenesis induced by colon cancer cells. Cell 199893705–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buskens C J, Van Rees B P, Sivula A.et al Prognostic significance of elevated cyclooxygenase 2 expression in patients with adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. Gastroenterology 20021221800–1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shi H, Xu J M, Hu N Z.et al Prognostic significance of expression of cyclooxygenase‐2 and vascular endothelial growth factor in human gastric carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 200391421–1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sheehan K M, Sheahan K, O'Donoghue D P.et al The relationship between cyclooxygenase‐2 expression and colorectal cancer. JAMA 19992821254–1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ristimäki A, Sivula A, Lundin J.et al Prognostic significance of elevated cyclooxygenase‐2 expression in breast cancer. Cancer Res 200262632–635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Erkinheimo T L, Lassus H, Finne P.et al Elevated cyclooxygenase‐2 expression is associated with altered expression of p53 and SMAD4, amplification of HER‐2/neu, and poor outcome in serous ovarian carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 200410538–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tucker O N, Dannenberg A J, Yang E K.et al Cyclooxygenase‐2 expression is up‐regulated in human pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res 199959987–990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kong G, Kim E K, Kim W S.et al Role of cyclooxygenase‐2 and inducible nitric oxide synthase in pancreatic cancer. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 200217914–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yip‐Schneider M T, Barnard D S, Billings S D.et al Cyclooxygenase‐2 expression in human pancreatic adenocarcinomas. Carcinogenesis 200021139–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Molina M A, Sitja‐Arnau M, Lemoine M G.et al Increased cyclooxygenase‐2 expression in human pancreatic carcinomas and cell lines: growth inhibition by nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs. Cancer Res 1999594356–4362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jacobs E J, Connell C J, Rodriguez C.et al Aspirin use and pancreatic cancer mortality in a large United States cohort. J Natl Cancer Inst 200496524–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takahashi M, Furukawa F, Toyoda K.et al Effects of various prostaglandin synthesis inhibitors on pancreatic carcinogenesis in hamsters after initiation with N‐nitrosobis(2‐oxopropyl)amine. Carcinogenesis 199011393–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schuller H M, Zhang L, Weddle D L.et al The cyclooxygenase inhibitor ibuprofen and the FLAP inhibitor MK886 inhibit pancreatic carcinogenesis induced in hamsters by transplacental exposure to ethanol and the tobacco carcinogen NNK. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2002128525–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yip‐Schneider M T, Sweeney C J, Jung S H.et al Cell cycle effects of nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs and enhanced growth inhibition in combination with gemcitabine in pancreatic carcinoma cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2001298976–985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Siironen P, Ristimäki A, Nordling S.et al Expression of COX‐2 is increased with age in papillary thyroid cancer. Histopathology 200444490–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robertson R P. Dominance of cyclooxygenase‐2 in the regulation of pancreatic islet prostaglandin synthesis. Diabetes 1998471379–1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ristimäki A, Nieminen O, Saukkonen K.et al Expression of cyclooxygenase‐2 in human transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Am J Pathol 2001158849–853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saukkonen K, Nieminen O, van Rees B.et al Expression of cyclooxygenase‐2 in dysplasia of the stomach and in intestinal‐type gastric adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 200171923–1931. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Merati K, Siadaty M, Andea A.et al Expression of inflammatory modulator COX‐2 in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and its relationship to pathologic and clinical parameters. Am J Clin Oncol 200124447–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Okami J, Yamamoto H, Fujiwara Y.et al Overexpression of cyclooxygenase‐2 in carcinoma of the pancreas. Clin Cancer Res 199952018–2024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koshiba T, Hosotani R, Miyamoto Y.et al Immunohistochemical analysis of cyclooxygenase‐2 expression in pancreatic tumours. Int J Pancreatol 19992669–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bansal P, Sonnenberg A. Pancreatitis is a risk factor for pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterology 1995109247–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lowenfels A B, Maisonneuve P, Cavallini G.et al Pancreatitis and the risk of pancreatic cancer. International Pancreatitis Study Group. N Engl J Med 19933281433–1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lowenfels A B, Maisonneuve P, DiMagno E P.et al Hereditary pancreatitis and the risk of pancreatic cancer. International Hereditary Pancreatitis Study Group. J Natl Cancer Inst 199789442–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ryu B, Jones J, Hollingsworth M A.et al Invasion‐specific genes in malignancy: serial analysis of gene expression comparisons of primary and passaged cancers. Cancer Res 2001611833–1838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCawley L J, Matrisian L M. Tumor progression: defining the soil round the tumor seed. Curr Biol 200111R25–R27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schlosser W, Schlosser S, Ramadani M.et al Cyclooxygenase‐2 is overexpressed in chronic pancreatitis. Pancreas 20022526–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kokawa A, Kondo H, Gotoda T.et al Increased expression of cyclooxygenase‐2 in human pancreatic neoplasms and potential for chemoprevention by cyclooxygenase inhibitors. Cancer 200191333–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eibl G, Reber H A, Wente M N.et al The selective cyclooxygenase‐2 inhibitor nimesulide induces apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cells independent of COX‐2. Pancreas 20032633–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]