Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumours (IMFTs) are rare, distinct clinicopathological entities characterised by a dense inflammatory cell component amid myofibroblastic proliferation. Although the lung is the site commonly associated, there are reports of extra pulmonary involvement. IMFTs of the gastrointestinal tract are extremely rare and there have been only three confirmed cases of involvement of the appendix. These benign tumours have distinctive clinicopathological features that distinguish them from inflammatory fibroid polyps, gastrointestinal stromal tumours, smooth muscle tumours, sclerosing mesenteritis, lymphoma and other malignant tumours.1,2,3,4,5,6 This letter highlights the clinical and immunohistological features of an IMFT of the appendix.

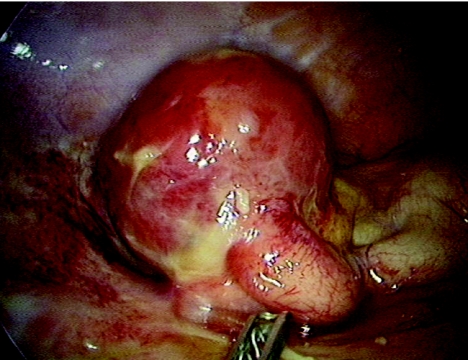

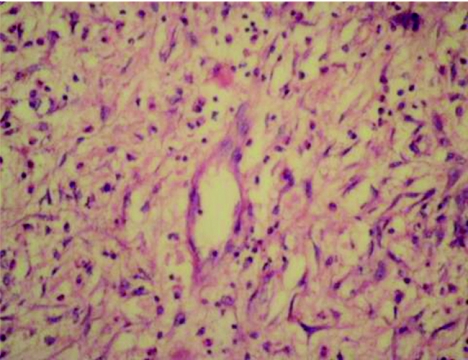

A 34‐year‐old man presented with progressively worsening colicky pain in the right lower abdomen for the past 3 days, associated with low‐grade fever and two episodes of vomiting. Clinical examination showed a tender right lower quadrant with a vague mass. Investigations were unremarkable except for a raised total white cell count and an increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate (12 800 cells/mm3 and erythrocyte sedimentation rate 48 mm/h, respectively). Abdominal ultrasound showed features of an appendicular mass. Laparoscopy showed a diffusely inflamed, oedematous appendix adherent to the surrounding small bowel and covered by omentum. A rounded, well‐delineated mass of about 6 cm in diameter, arising from the mid‐third of the appendix along its antimesenteric border was also noticed. Mesenteric adenopathy was not obviously evident. The appendix, with the mass, was carefully separated from the surrounding intestine and an enbloc resection, including the mesoappendix, was carried out. The appendix measured 8×7×4 cm and the whole specimen weighed 40 g; the mass arising in the mid‐third of the appendix measured 6×5 cm (fig 1). The appendix showed diffuse inflammation with the mid‐third stretched over the mass. The appendix was slit longitudinally and no obvious breach in mucosal continuity was noted; inflammatory changes were seen within, and luminal obstruction at the level of the mass was evident. A cut section showed a greyish‐pink smooth‐surfaced mass with a focal area of necrosis surrounding a fecalith measuring 13 mm in diameter (fig 2). A small 8 mm lymph node was identified in the mesentery. Sections showed appendicular mucosa with ulceration, lymphoid hyperplasia and acute inflammatory cells. Sections from the mass showed spindle‐shaped myofibroblasts amid inflammatory cells consisting of eosinophils, lymphocytes, plasma cells and neutrophils in order of frequency (fig 3). Blood vessels with irregular blood spaces of varying sizes were seen. No evident granulomatous changes (negative staining for acid‐fast bacilli) or cellular atypia were observed. The lymph node showed features of reactive hyperplasia. Culture showed Escherichia coli. Immunohistochemistry showed intensely positive vimentin, smooth muscle actin staining in spindle cells and negative staining for neurone‐specific enolase, S‐100, desmin, CD34 and CD117. The patient's postoperative recovery was uneventful and he has no evidence of recurrence nearly 18 months after surgery.

Figure 1 Gross appearance of appendicular mass (inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour).

Figure 2 Cut section of appendicular mass showing abscess and fecalith in the centre.

Figure 3 Inflammatory cells consisting of eosinophils, plasma cells, lymphocytes, neutrophils, histiocytes and spindle‐shaped myofibroblasts (haematoxylin and eosin staining ×400).

Considered as an aberrant or exaggerated response of the tissues to a chronic inflammatory process, IMFT could be a histological expression of an infective or reparatory process and, occasionally, a true neoplasm.2 The true incidence of these tumours is unknown; in addition, as immunostaining is not routine in most laboratories, many cases probably go undiagnosed and unreported. Generally singular, with no specific age or sex predilection,3 their clinical manifestations usually relate to the organ associated, with no specific features for preoperative diagnosis. These are firm, solid, well‐encapsulated tumours of varying sizes, with a gritty sensation on cutting and occasional areas of necrosis. Histologically, the tumours consist of dense infiltration, with inflammatory plasma cells, histiocytes, lymphocytes and eosinophils amid well‐populated areas of spindle‐shaped myofibroblasts. Three histological patterns are described: fibromyxoid or vascular, proliferating and sclerosing. Atypia is rare, with few or no mitoses.3 The histological manifestations range from inflammatory cell proliferation to neoplastic spindle‐cell formation, with various parts of the same lesion showing a wide range of processes. Varied aetiological factors include chronic irritating factors5 and infections caused by Helicobacter pylori, E coli, Epstein–Barr virus, for example. In our case, the fecalith may have been a contributory factor that exaggerated the inflammatory response. Microabscesses or cavities with necrosis have been described; not all have yielded any detectable growth.3,5 Immunostaining positivity for smooth‐muscle‐specific actin and vimentin is helpful in confirming the myofibroblastic origin, whereas reactivity to CD34 is negative. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase reactivity has been recently detected in some spindle‐cell components of these tumours.3

Specific immunostaining techniques can help differentiate these tumours, with a good prognosis. Treatment constitutes complete excision with lymph node clearance, although the involvement of nodes is an exception rather than the rule. Recurrences and rare examples of malignant transformation have been reported.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Narasimharao K L, Malik A K, Mitra S K.et al Inflammatory pseudotumor of the appendix. Am J Gastroenterol 19847932–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonnet J P, Basset T, Dijoux D. Abdominal inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors in children: report of an appendiceal case and review of the literature. J Pediatr Surg 1996311311–1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maklouf H R, Sobin L H. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors (inflammatory pseudotumors) of the gastrointestinal tract: how closely are they related to inflammatory fibroid polyps. Hum Pathol 200233307–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karnak I, Senocak M E, Ciftci A O.et al Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors in children: diagnosis and treatment. J Pediatr Surg 200136908–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee S‐H, Fang Y‐C, Luo J‐P.et al Inflammatory pseudotumour associated with chronic persistent Eikenella corrodens infection: a case report and brief review. J Clin Pathol 200356868–870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vijayaraghavan R, Sujatha Y, Santosh K V.et al Inflammatory fibroid polyp of jejunum causing jejuno‐jejunal intussusception. Indian J Gastroenterol 200423190–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]