Abstract

The simultaneous manifestation of different lymphomas in the same patient or even in the same tissue, defined as composite lymphoma, is very rare. The exceptional case of a patient who, presented with simultaneous manifestation of three different lymphomas after 30 years of successful treatment of a nodal T cell lymphoma is reported here. The three lymphomas were: (1) primary cutaneous marginal zone B cell lymphoma (MZBL); (2) nodal Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)‐associated classic Hodgkin's lymphoma (cHL) of the B cell type; and (3) peripheral T cell lymphoma coexisting in the skin and cervical lymph node. Immunohistochemical and molecular analyses showed different clonal origins of EBV‐negative cutaneous MZBL and EBV‐positive B cell cHL and, in addition, the presence of the same clonal T cell population in the skin and lymph node. The simultaneous occurrence of three different, clonally unrelated lymphomas in one patient at the same time has not been reported yet.

The simultaneous occurrence of unrelated, morphologically and genetically distinct lymphomas in the same mass is a rare finding and is defined as composite lymphoma.1,2,3 In many cases the so‐called composite lymphomas are—despite morphological differences—genetically identical owing to different transformation events of a common precursor cell.4 This holds especially true for the occurrence of classic Hodgkin's lymphoma (cHL) and non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma in the same patient, where fundamental morphological and immunophenotypical discrepancies superimpose onto the common cellular origin.5,6

Case report

In 2003, a 65‐year‐old female patient presented with cutaneous brownish, infiltrated nodules up to 3 cm in size on both forearms and on the right lower leg. Computed tomography scans showed enlarged lymph nodes in the cervical and retroperitoneal region. No lymphoma manifestation was detected in the bone marrow specimen. Serological analysis for the presence of antibodies against Borrelia was negative. Thirty years previously (in January 1973), a nodal T cell lymphoma (TCL) had been diagnosed after presentation of B symptoms and widespread lymphadenopathy; it was successfully treated with 15 weekly cycles of combined chemotherapy, resulting in complete remission by May 1973.

Results and discussion

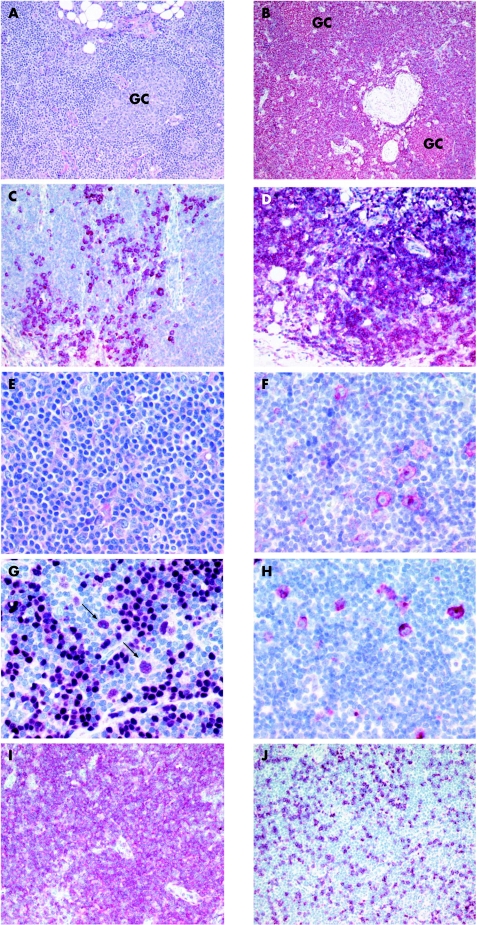

Histological analyses of a cutaneous nodule carried out in 2003 showed a lymphoid infiltrate in the deeper corium and in adjacent subcutaneous tissue consisting of sheets of cells with small, indented nuclei and plasma cells (fig 1A). Some germinal centres were visible embedded in this infiltrate. Immunohistological examination showed a prominent CD20‐positive B cell population, with a partial plasmacellular and a monotypic expression of immunoglobulin κ (fig 1B,C). An Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) infection was excluded by negative EBV‐encoded RNA in situ hybridisation. This B cell infiltrate was classified as primary cutaneous marginal zone B cell lymphoma (MZBL; table 1). A clonal B cell population was found by the concordant results of the immunoglobulin H (IgH) PCR using different primer sets (table 2).

Figure 1 Histological and immunophenotypical examination of the cutaneous nodule (A–D). (A) Sheets of cells with small, indented nuclei and plasma cells, embedded in some germinal centres (Giemsa, original magnification ×150). (B) The lymphoid infiltrate is strongly positive for CD20 (alkaline phosphatase‐anti‐alkaline phosphatase (APAAP), original magnification ×120). (C) A monotypic expression of Igκ (APAAP, original magnification ×150). (D) Identification of an atypical T cell population showing a clear predominance of CD4 expression (APAAP, original magnification ×150). Histological and immunophenotypical examination of the lymph node excised in 2003 (E–J). (E) Scattered infiltration of large atypical cells displaying morphological features of Hodgkin's and Reed–Sternberg (HRS) cells (Giemsa, original magnification ×200). (F) HRS cells were positive for CD30 (APAAP, original magnification ×350) and (G) positive for B cell‐specific activator protein; see arrows and note B cell‐specific activator protein negative lymphocytes surrounding HRS cells (APAAP, original magnification ×350). (H) HRS cells were positive for EBV, as indicated by immunoreactivity for latent membrane protein (LMP) 1 (APAAP, original magnification ×350). (I) Identification of an atypical T cell population showing a clear predominance of CD4 expression (APAAP, original magnification ×150). (J) Only a few lymphoid cells express CD8 (APAAP, original magnification ×150).

Table 1 Immunophenotypic features of all lymphomas.

| Skin (2003) | Lymph node (2003) | Lymph node (1973) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MZBL | TCL | CHL | TCL | TCL | |

| CD3 | − | + | − | + | + |

| CD4 | − | + | − | + | + |

| CD8 | − | − | − | − | − |

| β chain TCR | − | −* | − | −* | −* |

| CD20 | + | − | − | − | − |

| Igκ | + | − | − | − | ND |

| Igλ | − | − | − | − | ND |

| IgD | − | − | ND | ND | ND |

| IgG | − | − | ND | ND | ND |

| CD30 | − | − | + | − | − |

| CD15 | − | − | + | − | − |

| BCL‐2 | + | − | − | − | − |

| BSAP/PAX‐5 | ND | ND | + | − | ND |

| LMP‐1 | − | − | + | − | − |

+, positive; −, negative; BCL, B cell lymphoma; BSAP, B cell‐specific activator protein; CD, curative dose; CHL, classic Hodgkin's lymphoma; LMP, latent membrane protein; MZBL, marginal zone B cell lymphoma; ND, not done; TCL, T cell lymphoma; TCR, T cell receptor;

*Most of the neoplastic T cells show a loss of TCR‐β expression.

Table 2 Junctional sequences of the clonal IgH and TCRγ rearrangements.

| IgH | V | N1 | D | N2 | J | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skin | V3‐30*02 | ‐TGTGCGA | G | CCGGAACC | TAAGGGCTGTG | ACTACTTTGACTACTGG‐J4*02 |

| LN | V3‐23*01 | ‐TGTGCGAAAGA | CC | TACCATGGT | — | ACTAATTTGCCTACTGG‐J4*02 |

| TCRγ | V | N | J | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skin | V9*01 | ‐TGTGCCTT | CCGGCCCG | AAGAAACTCTTT‐J2*01 | ||

| LN | V9*01 | ‐TGTGCCTT | CCGGCCCG | AAGAAACTCTTT‐J2*01 | ||

IgH, immunoglobulin H; LN, lymph node; TCR, tumour necrosis factor; —, no N nucleotides.

Histological analysis of an enlarged cervical lymph node taken in 2003 showed scattered atypical large cells displaying the cytomorphological features of HRS cells, with a corresponding immunophenotype showing positivity for CD30, CD15 and the B cell transcription factor PAX‐5, whereas CD20 was not detectable (fig 1E–G; table 1). An EBV infection of the HRS cells was shown by their positivity for the EBV‐encoded (latent membrane protein 1) protein (fig 1H) and positive EBV‐encoded RNA in‐situ hybridisation. A nodal EBV‐associated cHL of B cell origin was diagnosed. A clonal IgH rearrangement was not demonstrable in the whole tissue DNA extract by PCR analysis. However, the analysis of isolated single CD30‐positive HRS cells by single‐copy IgH PCR disclosed the presence of a clonal IgH gene rearrangement in the HRS cell population, showing their B cell genotype. Sequence comparison of the clonal IgH rearrangements detected in skin (MZBL) and in the HRS cells of the lymph node (cHL) clearly showed that the tumour cells of the EBV‐negative cutaneous MZBL and EBV‐positive nodal cHL were derived from different precursor cells (table 2).

This case became highly exceptional because of the identification of an atypical CD3‐positive and CD4‐positive and partially T cell receptor (TCR)‐β‐negative T cell population present in the skin and lymph node with MZBL and cHL, respectively (fig 1D,I,J). A reactive nature in this atypical T cell population seems to be highly unlikely, owing to the same dominant clonal TCR‐γ gene rearrangement in the biopsy specimen of the skin and of the lymph node (table 2). These morphological and molecular findings strongly argue for the presence of the same CD4‐positive peripheral TCL in the skin and lymph node. Because of its simultaneous occurrence in the same tissue with both cutaneous MZBL and nodal cHL, the diagnosis of two different composite lymphomas was established: (1) cutaneous MZBL and peripheral TCL; and (2) nodal cHL and peripheral TCL.

Reassessment of the lymph node biopsy specimen taken 30 years ago showed a proliferation of medium‐sized atypical lymphoid cells that proved to be of T‐helper cell origin owing to the expression of CD2, CD3 and CD4. Moreover, most atypical T cells lacked expression of the TCR‐β chain (table 1). Unfortunately, no TCR‐γ‐specific amplificates were generated owing to an almost complete degradation of the DNA as shown by quality control PCR. Therefore, the relationship between the TCL of 1973 and that of 2003 remains speculative, despite the expression of CD4 by the tumour cells of both lymphomas.

The patient received four cycles of systemic chemotherapy in accordance with the BEACOPP (Belcomycin Etoposide Adriamycin Cyclophosphamide Oncovin Procarbazine Prednisone) protocol, followed by two cycles of COPP (Cyclophosphamide Oncovin Procarbazine Prednisone) chemotherapy. This treatment resulted in a complete remission of all lymphomas.

Composite lymphomas occur as a combination of either two different B cell or two different T cell lymphoma components or one B cell lymphoma and one TCL. Composite lymphomas consisting of cHL and B cell NHL are described in the literature.5,6,7 In many of these cases an origin of a common precursor B cell with identical IgH gene rearrangements of both B cell lymphomas could be documented.5,6 In contrast, true composite lymphomas consisting of two clonally unrelated lymphomas, such as cHL and TCL as in our patient, are rare.3

Several explanations for the development of cHL and NHL in the same patient, such as induction by chemotherapeutic agents or immunological defects, have been discussed.8 In fact, an almost threefold risk of cHL in patients successfully treated for NHL has been reported.9 Especially, lymphomas occurring with a delay of many years after chemotherapy of a first lymphoma are often considered to be treatment induced. Other known factors associated with high rates of lymphoma are autoimmune diseases such as Sjögren's syndrome, primary or acquired immunodeficiencies and autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome (ALPS).10,11 ALPS is a rare disorder of lymphocyte homoeostasis associated with germline FAS mutations. It usually occurs in early childhood and is characterised by lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly and autoimmune disorders. The risk of developing cHL or NHL in patients with ALPS was recently reported to be 51 and 14 times, respectively, higher than expected.10 However, as all these predisposing factors were excluded in our patient, the simultaneous occurrence of three different lymphomas is most probably induced by chemotherapy.

In conclusion, immunohistological and molecular analyses of our patient showed manifestation of three genetically unrelated lymphomas: (1) primary cutaneous MZBL; (2) nodal EBV‐associated cHL of the B cell type; and (3) peripheral TCL coexisting in the skin and cervical lymph node. This case shows the possible occurrence of different lymphomas in one patient, which should be distinguished by clinicians and pathologists to enable disease‐specific treatment.

Acknowledgements

We thank H Lammert and H‐H Müller for their excellent technical assistance.

Abbreviations

ALPS - autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome

APAAP - alkaline phosphatase anti‐alkaline‐phosphatase

cHL - classic Hodgkin's lymphoma

EBV - Epstein–Barr virus

HRS - Hodgkin's and Reed–Sternberg

IgH - immunoglobulin H

MZBL - marginal zone B cell lymphoma

TCL - T cell lymphoma

TCR - T cell antigen receptor

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

References

- 1.Custer R P.Proceedings of the second national cancer conference. Vol 1. New York: American Cancer Society, 1954554–557.

- 2.National Cancer Institute Sponsored study of classifications of non‐Hodgkin's lymphomas: summary and description of a working formulation for clinical usage. The Non‐Hodgkin's Lymphoma Pathologic Classification Project. Cancer 1982492112–2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steinhoff M, Hummel M, Assaf C.et al Cutaneous T cell lymphoma and classic Hodgkin lymphoma of the B cell type within a single lymph node: composite lymphoma. J Clin Pathol 200457329–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jaffe E S, Zarate‐Osorno A, Medeiros L J. The interrelationship of Hodgkin's disease and non‐Hodgkin's lymphomas—lessons learned from composite and sequential malignancies. Sem Diagn Pathol 19929297–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marafioti T, Hummel M, Anagnostopoulos I.et al Classical Hodgkin's disease and follicular lymphoma originating from the same germinal center B cell. J Clin Oncol 1999173804–3809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brauninger A, Hansmann M L, Strickler J G.et al Identification of common germinal‐center B‐cell precursors in two patients with both Hodgkin's disease and non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med 19993401239–1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zettl A, Rudiger T, Marx A.et al Composite marginal zone B‐cell lymphoma and classical Hodgkin's lymphoma: a clinicopathological study of 12 cases. Histopathology 200546217–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amini R M, Enblad G, Sundstrom C.et al Patients suffering from both Hodgkin's disease and non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma: a clinico‐pathological and immuno‐histochemical population‐based study of 32 patients. Int J Cancer 199771510–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Travis L B, Gonzalez C L, Hankey B F.et al Hodgkin's disease following non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma. Cancer 1992692337–2342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fisher S G, Fisher R I. The epidemiology of non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma. Oncogene 2004236524–6534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Straus S E, Jaffe E S, Puck J M.et al The development of lymphomas in families with autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome with germline Fas mutations and defective lymphocyte apoptosis. Blood 200198194–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]