Abstract

A 55‐year‐old African‐American man with clinical stage T1c prostate cancer underwent prostatectomy. Non‐caseating, epithelioid granulomata adjacent to the anterior fibromuscular stroma were found incidentally. The granulomata included Langhans giant cells with rare conchoidal bodies. The distribution of the granulomata was not that of non‐specific granulomatous prostatitis centred around ducts and glands. By immunohistochemistry, the epithelioid cells were positive for angiotensin‐converting enzyme. The histological appearance suggested sarcoidosis, which was confirmed by the clinical history. Four years earlier, the patient had been treated for sarcoidosis.

Only four cases of prostatic sarcoidosis have been reported.1,2,3,4 Three of these patients had a known history of sarcoidosis. One of the patients had a prostate biopsy for a nodule. In addition to prostatic carcinoma, granulomata consistent with sarcoid were also found.3

Here, an additional case of sarcoidosis and carcinoma involving the prostate is reported.

Case presentation

A 55‐year‐old African‐American man was found to have a prostate‐specific antigen level of 6.53 ng/ml on screening. Digital rectal examination was unremarkable.

The patient underwent 10 cores transrectal ultrasound‐guided biopsies, which showed a prostatic adenocarcinoma with a Gleason Score of 5+3 = 8. The clinical stage was T1c and the patient underwent prostatectomy in January 2003.

The radical prostatectomy contained seven foci of adenocarcinoma with a Gleason Score of 3 and 4 in the largest tumour. The pathological stage was T3a.

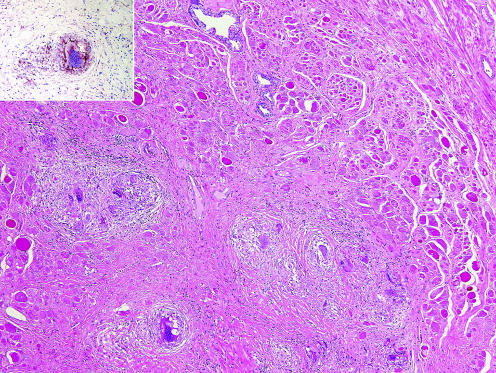

The unusual finding was a group of non‐caseating, epithelioid granulomata adjacent to the anterior fibromuscular stroma and to one of the tumours (fig 1). The granulomata included Langhans‐type giant cells, one of which contained a calcified conchoidal (Schaumann) body. By immunohistochemistry, the epithelioid cells were positive for angiotensin‐converting enzyme (fig 1, inset). The distribution of the granulomata was not that of non‐specific granulomatous prostatitis where the granulomas are centred around the ducts and glands. No necrosis was found that would suggest a granulomatous inflammation owing to microorganisms. The distinctive appearance of the post‐transurethral resection granuloma was not seen. The histological appearance suggested sarcoidosis. Additional clinical information indicated that the patient had been treated for sarcoidosis 4 years earlier.

Figure 1 Non‐caseating, epithelioid granulomata in anterior fibromuscular stroma (H&E, ×40). Inset, angiotensin‐converting enzyme (ACE) positive in epithelioid histiocytes (anti‐ACE, ×160).

Discussion

Sarcoidosis rarely involves the prostate (table 1).

Table 1 Cases of sarcoidosis in prostate.

| Authors | Year | Number of cases | Age (years) | History of sarcoidosis | Type of specimen |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schaumann1 | 1936 | 1/2 | 42 | Yes | Autopsy |

| Ricker and Clark4 | 1949 | 1/21 | 25 | Yes | Autopsy |

| Todd and Garnick3 | 1980 | 1 | 78 | Yes | Biopsy |

| Morris et al2 | 1993 | 1 | 28 | Suspicious | Biopsy |

| This study | 2006 | 1 | 55 | Not known* | Prostatectomy |

*Not known at the time of prostatectomy.

In 1936, Schauman1 reported the first case of prostatic sarcoidosis in a patient with disseminated disease. In a review of 300 cases, including 22 autopsies, Ricker and Clark4 found only one case with prostatic involvement. Morris et al2 treated one patient with known sarcoidosis for “penile pain and reduced ejaculatory volume”. The biopsy specimen of the prostate showed numerous granulomata. Todd and Garnick3 reported a patient with known dermal sarcoidosis, who also had prostate involvement and prostatic carcinoma.

Except for the case described by Morris et al2, none of the patients had symptoms referable to the prostate. The diagnosis was made either at autopsy or incidentally at prostatectomy for cancer. In a review of patients with pulmonary and/or hilar lymph node sarcoidosis associated with malignant tumours, Brincker and Wilbek5 described one patient with concomitant prostatic carcinoma but no mention was made of prostatic sarcoid. In our patient, the presence of non‐caseating, epithelioid granulomata not associated with the glandular elements or necrosis led us to consider sarcoidosis. A detailed medical history confirmed this suspicion. The diagnosis was made through transbronchial biopsy more than 4 years earlier when the patient presented with brachial plexopathy and pulmonary symptoms. The patient had been treated with a course of steroids. Considering the rarity of prostatic sarcoidosis, this diagnosis is usually not entertained. A detailed clinical history, radiological imaging studies, cultures and appropriate histological investigation to exclude other entities are necessary for the correct diagnosis.

Footnotes

Competing interests:None.

References

- 1.Schaumann J. Lymphogranulomatosis benigna in the light of prolonged clinical observations and autopsy findings. Br J Derm Syph 193648399–446. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morris S B, Gordon E M, Corbishley C M. Prostatic sarcoidosis. Review of genitourinary sarcoidosis. Br J Urol 199372462–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Todd RF I I I, Garnick M B. Prostatic adenocarcinoma, sarcoidosis and hypercalcemia: an unusual association. J Urol 1980123133–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ricker W, Clark M. Sarcoidosis. A clinicopathological review of three hundred cases including twenty‐two autopsies. Am J Clin Pathol 194919725–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brincker H, Wilbek E. The incidence of malignant tumours in patients with respiratory sarcoidosis. Br J Cancer 197429247–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]