Abstract

A case in which an embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma of the cervix and an ovarian Sertoli–Leydig cell tumour of intermediate differentiation occurred in a 13‐year‐old girl is described. Although initially considered as a chance association, a review of the literature showed the co‐occurrence of these two uncommon neoplasms in three previous cases. The reason for this association, which is thought to be more than coincidental, is not known, although an underlying genetic abnormality is a possibility. The ovarian tumour in this case was characterised by the presence of foci of cells with extremely pleomorphic nuclei, which initially raised the possibility of metastatic rhabdomyosarcoma. These were interpreted as foci of bizarre nuclei within the Sertoli–Leydig cell tumour.

When two or more neoplasms occur in the same patient, this is generally a chance association. However, when two rare tumours coexist, the question of an association that is more than coincidental is raised. For instance, the occurrence of gastric epithelioid leiomyosarcoma (now redesignated as a gastrointestinal stromal tumour), pulmonary chondroma and extra‐adrenal paraganglioma in several patients resulted in the description of Carney triad.1,2 In this report, we describe the coexistence of a cervical embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma and an ovarian Sertoli–Leydig cell tumour in a 13‐year‐old girl. Although we initially considered this as a chance association, a review of the published literature showed three other similar reported cases,3,4 strongly suggesting a more than coincidental association between these two uncommon neoplasms. The basis for the association is not clear, but in highlighting this we speculate on possible reasons.

Case report

A 13‐year‐old Indian girl with no previous medical problems presented with mild hirsutism and change in voice. Menarche was at the age of 12 years, and this was followed by a period of amenorrhoea for 9 months. She was found to have a cervical polyp, which was avulsed. Subsequent radiological investigations performed immediately after the histological diagnosis rendered on the cervical polyp showed a mass in the right ovary measuring 4 cm in maximum dimension. Right salpingo‐oophorectomy was performed. The case is recent and we have no significant follow‐up.

Pathological findings

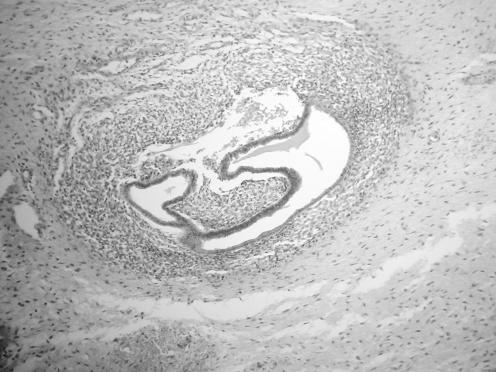

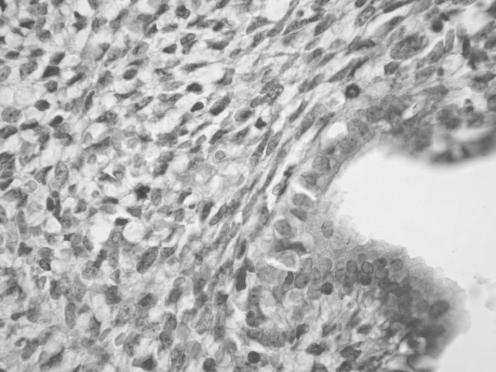

The cervical polyp measured 3 cm in maximum dimension. Histological examination showed benign endocervical glands on the surface and within the substance of the lesion. The stroma had a myxoid appearance with an increased cellularity around the glands resulting in a cambium layer (fig 1). The cellular component of the stroma was composed of regular spindle cells with hyperchromatic nuclei and easily identifiable mitotic figures (in areas 1–2 per high power field) within the cambium layer (fig 2). Classical rhabdomyoblasts with cross‐striations were not identified. No cartilaginous elements were seen. The stromal spindle shaped cells stained focally positive with desmin, and exhibited focal nuclear positivity with myogenin. A diagnosis of embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma was made.

Figure 1 Cervical embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma where stromal cells condense around glandular elements forming a cambium layer.

Figure 2 High power view of cervical embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma showing hyperchromatic spindle shaped stromal cells with mitotic figures located around a gland.

The ovary weighed 25 g and measured 4×4×4 cm. The cut surface was grey‐brown in colour.

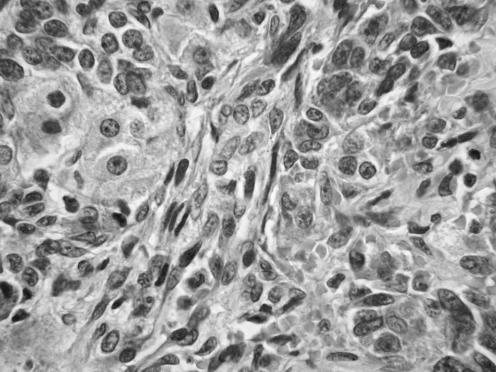

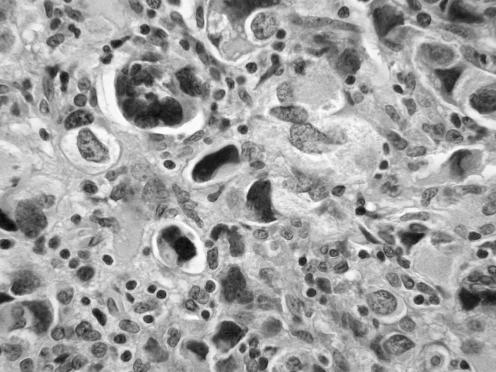

Histological examination showed a low power lobulated architecture with large cellular aggregates separated by hyalinised and oedematous stroma. The cellular aggregates were composed of cords and solid tubules of Sertoli cells with easily identifiable Leydig cells present especially at the periphery (fig 3), in keeping with a Sertoli–Leydig cell tumour of intermediate differentiation. No heterologous elements were present. Focally, collections of cells with highly pleomorphic hyperchromatic nuclei were present (fig 4). Many of these nuclei were multilobed. Both the Sertoli and Leydig cell components stained diffusely positive with α inhibin and calretinin and were focally positive with desmin. The pleomorphic cells were focally positive with α inhibin and desmin.

Figure 3 High power view of ovarian Sertoli–Leydig cell tumour illustrating cords and solid tubules of Sertoli cells together with Leydig cells containing abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm.

Figure 4 Foci of cells with extremely bizarre multilobed nuclei in Sertoli–Leydig cell tumour.

Discussion

As far as we are aware, this is the fourth reported case of a cervical embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma coexisting with an ovarian Sertoli–Leydig cell tumour of intermediate differentiation. The first two cases were part of the largest reported series of cervical embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma by Daya and Scully.3 The fact that two of the patients, aged 23 years and 15 years, developed an ovarian Sertoli–Leydig cell tumour of intermediate differentiation 1 year and 3 years later was merely mentioned in passing and no association was speculated. The third case was reported by Golbang et al4 and these authors were the first to speculate on an association between the two neoplasms. In that case, the cervical neoplasm, which was discovered at the age of 14 years, preceded the ovarian tumour by 13 years. Given that cervical embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma and ovarian Sertoli–Leydig cell tumour are two uncommon, although not rare, neoplasms it is likely that their association is more than coincidental. The reason for the association is not clear, although a genetic linkage can be speculated. There may be parallels with syndromes such as Carney complex, which was originally described in a series of patients with lentigines, cardiac myxomas and various endocrine abnormalities and in which a chromosomal abnormality has now been mapped to 2p16 and 17q 22–24.5 It is interesting that abnormalities of chromosome 12 have been identified in both embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma and ovarian Sertoli–Leydig cell tumour,6,7 suggesting a possible linkage. The patient in our case had no other significant abnormality or medical history, although she had hirsutism secondary to androgenic elaboration by the Sertoli–Leydig cell tumour.

Cervical embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma (sarcoma botryoides), in contrast to its more common vaginal counterpart, most commonly occurs in the second and third decades of life (although it has been described in older patients)3,4,8,9,10,11 and usually presents as a cervical polypoid lesion. Classical rhabdomyoblasts with cross striations are not necessary for the diagnosis and were not seen in this case. A cambium layer with condensation of stromal cells around epithelial elements is a characteristic feature and cartilaginous tissue is present in a significant percentage of cases. The differential diagnosis may include a usual cervical or endometrial polyp, endometriosis, a fibroepithelial polyp, an endometrial stromal or a leiomyomatous neoplasm. The morphological appearance of a polypoid lesion containing benign epithelial elements with a malignant stromal component, which condenses around the epithelium may suggest an adenosarcoma. However, in cervical embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma the glandular elements are considered to be entrapped rather than an integral component of the tumour.

Ovarian Sertoli–Leydig cell tumour most often occurs in young women and commonly presents with virilisation and other symptoms secondary to hormone elaboration, as in this case.12,13,14 These are four morphological subtypes—namely, well, intermediate, poorly differentiated and retiform. Tumours of intermediate differentiation are most common.12 All four Sertoli–Leydig cell tumours reported in association with cervical embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma have been of intermediate differentiation.

The presence of collections of cells with bizarre nuclei within the Sertoli–Leydig cell tumour was unusual and initially resulted in consideration of metastatic rhabdomyosarcoma involving the ovarian neoplasm. However, we consider these to represent collections of bizarre nuclei which are occasionally found in otherwise typical ovarian sex cord‐stromal neoplasms, including granulosa and Sertoli–Leydig cell tumours.15 Morphologically these resemble the bizarre cells sometimes found in uterine leiomyomas and are probably degenerative in nature. Focal positivity of the bizarre cells with α inhibin suggested that they were of sex cord derivation. Desmin staining was performed on the ovarian tumour when the possibility of metastatic rhabdomyosarcoma was considered. The Sertoli and Leydig cell components and the bizarre cells were focally positive, and we make the point that ovarian sex cord‐stromal tumours may stain with muscle markers, including desmin.16 Indeed one of us (WGM) has observed that desmin is not uncommonly expressed in ovarian sex cord‐stromal tumours. We also mention the fact that collections of bizarre cells are rarely found in otherwise typical cervical embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma.17,18

Take home messages

We report the fourth described case of an association between cervical embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma and ovarian Sertoli–Leydig cell tumour.

We feel that the association of these two uncommon neoplasms is more than coincidental and may have a genetic basis.

In summary, we report a case in which a cervical embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma and an ovarian Sertoli–Leydig cell tumour of intermediate differentiation coexisted in a 13‐year‐old girl, the fourth documented example of this association. Given that these are two relatively uncommon neoplasms, we feel that the association is more than coincidental. The basis of the association is not known, but a genetic link seems likely.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Carney J A. The triad of gastric epithelioid leiomyosarcoma, functioning extra‐adrenal paraganglioma, and pulmonary chondroma. Cancer 197943374–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carney J A. The triad of gastric epithelioid leiomyosarcoma, pulmonary chondroma, and functioning extra‐adrenal paraganglioma: a five‐year review. Medicine (Baltimore) 198362159–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daya D, Scully R E. Sarcoma botryoides of the uterine cervix in young women: a clinicopathological study of 13 cases. Gynecol Oncol 198829290–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Golbang P, Khan A, Scurry J.et al Cervical sarcoma botryoides and ovarian Sertoli‐Leydig cell tumor. Gynecol Oncol 199767102–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sandrini F, Stratakis C. Clinical and molecular genetics of Carney complex. Mol Genet Metab 20037883–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bridge J A, Liu J, Qualman S J.et al Genomic gains and losses are similar in genetic and histologic subsets of rhabdomyosarcoma, whereas amplification predominates in embryonal with anaplasia and alveolar subtypes. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 200233310–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taruscio D, Carcangiu M L, Ward D C. Detection of trisomy 12 on ovarian sex cord stromal tumors by fluorescence in situ hybridization. Diagn Mol Pathol 1993294–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miyamoto T, Shiozawa T, Nakamura T.et al Sarcoma botryoides of the uterine cervix in a 46‐year‐old woman: case report and literature review. Int J Gynecol Pathol 20042378–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ober W B. Sarcoma botryoides of the cervix uteri: a case report in a 75‐year‐old woman. Mt Sinai J Med 197138363–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brand E, Berek J S, Nieberg R K.et al Rhabdomyosarcoma of the uterine cervix. Sarcoma botryoides. Cancer 1987601552–1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vlahos N P, Matthews R, Veridiano N P. Cervical sarcoma botryoides. A case report. J Reprod Med 199944306–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Young R H, Scully R E. Ovarian Sertoli‐Leydig cell tumors. A clinicopathological analysis of 207 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 19859543–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Young R H, Scully R E. Well‐differentiated ovarian Sertoli‐Leydig cell tumors: a clinicopathological analysis of 23 cases. Int J Gynecol Pathol 19843277–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Young R H, Scully R E. Ovarian Sertoli‐Leydig cell tumors with a retiform pattern: a problem in histopathologic diagnosis. A report of 25 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 19837755–771. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Young R H, Scully R E. Ovarian sex cord‐stromal tumors with bizarre nuclei: a clinicopathologic analysis of 17 cases. Int J Gynecol Pathol 19831325–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Santini D, Ceccarelli C, Leone O.et al Smooth muscle differentiation in normal human ovaries, ovarian stromal hyperplasia and ovarian granulosa‐stromal cells tumors. Mod Pathol 1995825–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caruso R A, Napoli P, Villari D.et al Anaplastic (pleomorphic) subtype embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma of the cervix. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2004270278–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Houghton J P, McCluggage W G. Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma of the cervix with focal pleomorphic areas. J Clin Pathol 20066088–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]