Abstract

Aims

To report three cases of serous cystadenoma and endocrine tumour in the same pancreas, to review the literature and to evaluate the clinicopathological features of the tumours.

Cases

Three women (71, 57 and 31 years old) were admitted to hospital, two for diseases unrelated to the pancreas and the third for increasing obstructive jaundice in von Hippel‐Lindau disease. Preoperative examination showed two distinct lesions in the first patient and only cystic lesions in the other two.

Results

Histological examination of the pancreas showed one serous oligocystic adenoma associated with a benign, well‐differentiated endocrine tumour, one serous oligocystic adenoma associated with an endocrine microadenoma, and a von Hippel‐Lindau‐related cystic neoplasm with a well‐differentiated endocrine carcinoma.

Conclusions

Serous cystadenoma associated with endocrine tumour shows some clinicopathological differences with respect to the two tumours considered separately, and with respect to von Hippel‐Lindau‐related cases, although there is no convincing evidence at present to justify considering this association as a separate entity.

Although the association of endocrine pancreatic tumours with cystadenomas is already known in patients with von Hippel‐Lindau disease (VHL), the same association unrelated to VHL is quite rare but not exceptional. To date, six cases have been reported in the literature.1,2,3,4,5,6 Another case of pancreatic cystadenoma associated with a neuroendocrine tumour was reported by Persaud and Walrond in 1971,7 but the pathological findings described in that paper suggest that the cystadenoma was mucinous in type.

Serous cystadenomas are tumours derived from intralobular duct cells (ductular and centroacinar cells), most of them benign. They are classically subdivided into five main types: serous microcystic adenoma (SMA), serous oligocystic ill‐defined adenoma (SOIA), von Hippel‐Lindau‐associated cystic neoplasm (VHL‐CN), solid serous adenoma and the malignant serous cystic neoplasm (SCN), called serous cystadenocarcinoma. SMA is the most frequent, showing a predominant occurrence in women, with age at presentation of 66 years, sharp demarcation from surrounding tissue, a central scar and a honeycomb appearance. SOIA is less frequent than SMA, does not show any predilection for sex, and the age of incidence is approximately 60 years, but there have also been some cases reported in children. VHL‐CN consists of an aggregation of cysts, often multiple, with no sex predilection. The solid type of cystadenoma shares the same cytological appearance and has a compact structure. Serous cystadenocarcinoma has histological features similar to those of serous cystadenoma, with mild focal nuclear pleomorphism. The aetiology and pathogenesis of these tumours are unknown.

The causes of endocrine tumours have not been identified, apart from those arising in multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) syndrome type 1. Although endocrine tumours have been suggested to derive from multipotent ductular stem cells, there is no definitely convincing evidence to support this hypothesis. At least some endocrine tumours seem to originate from intralobular serous‐type ductules.8 In a recent study, Vortmeyer et al,9 focusing their attention on normal pancreatic tissue from patients with MEN1, observed a spectrum of morphological changes ranging from obvious tumour to early neoplastic changes.

The coexistence of both pancreatic endocrine tumour and serous cystadenoma has been reported only six times in the literature, always as isolated cases. The first case was published in 1993 by Heresbach et al,1 and was a pancreatic serous cystadenoma associated with a cystadenocarcinoma and a non‐functioning endocrine tumour in a 70‐year‐old patient. From 19962 to 2005,6 four other cases of serous cystadenoma associated with endocrine tumour were reported.

The aim of this work is to emphasise that the association of pancreatic serous cystadenoma (oligo‐ or microcystic) with endocrine tumour is not as rare as believed previously, when patients unaffected by VHL are also considered. This probably reflects the common embryogenic origin of the two tumours.

Patients' histories

Case 1

A 71‐year‐old woman was admitted to hospital for uterine leiomyomastosis; preoperative ultrasound ecography showed a left renal mass and a cystic pancreatic lesion. The medical history of both the patient and her family were unremarkable. A pancreatic computed tomography scan showed two distinct lesions at the body/tail level, one cystic and one solid. A total hysterectomy and left pancreasectomy were planned. Nephrectomy was performed about 2 months later, for technical reasons. No clinical signs of hormone hyperproduction were noted.

Case 2

A 57‐year‐old woman was admitted to hospital for resection of a pancreatic lesion discovered during preoperative examination for a left adnexal adenoma (previous histological bioptical diagnosis). An abdominal computed tomography scan showed a cystic pancreatic lesion measuring <1 cm at the body level, and gallbladder microlithiasis. The patient's history showed only type 2 diabetes. A left pancreasectomy was performed. The left adnexal neoplasm was not removed because it was non‐functioning, calcified and unchanged in size.

Case 3

A 31‐year‐old woman affected by von Hippel‐Lindau disease, with a history of resected right renal cell carcinoma (clear cell type), non‐resected left cerebellar haemangioblastoma and multiple liver angiomas, was admitted to hospital for progressing obstructive jaundice. An abdominal computed tomography scan showed a solid expansive neoplasm measuring up to 4 cm across at the head of the pancreas, with other cystic formations throughout the pancreas. A pylorum‐preserving duodeno‐cephalo‐pancreasectomy was performed.

Histological and immunohistochemical examination

Immunohistochemical analysis was performed on all pancreatic lesions, with antibodies against chromogranin A, synaptophysin and neurone‐specific enolase (NSE), and a panel for endocrine digestive tumours. Staining with periodic acid Schiff (PAS) and PAS staining with diastase digestion were performed on all cystic neoplasms. Antibodies used were: Ki67 (monoclonal mouse antibody, clone Mib1, diluted 1:200, Dako, Glostrup, Denmark), chromogranin A (monoclonal mouse antibody, clone DAK‐A3, diluted 1:100, Dako), synaptophysin (monoclonal mouse antibody, clone SY38, diluted 1:200, Dako), NSE (monoclonal mouse antibody, clone BBS/NC/VI‐H14, diluted 1:100, Dako), glucagons (polyclonal rabbit antibody, diluted 1:150, BioGenex, San Ramon, California, USA), insulin (polyclonal guinea pig antibody, diluted 1:100, BioGenex), vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (polyclonal rabbit antibody, diluted 1:800, BioGenex), somatostatin (polyclonal rabbit antibody, diluted 1:800, Dako), pancreatic polypeptide (polyclonal rabbit antibody, diluted 1:100, BioGenex), gastrin (polyclonal rabbit antibody, diluted 1:100, BioGenex) and CD34 (monoclonal mouse antibody, clone QBEND10, diluted 1:40, Immunotech, Marseilles, France). The insulae of normal pancreas surrounding the tumours were used as positive controls. CD10 (monoclonal mouse antibody, clone 56C6, diluted 1:40, Novocastra, Newcastle, UK) was assayed on the renal specimen.

Histological, histochemical and immunohistochemical examination results

Case 1

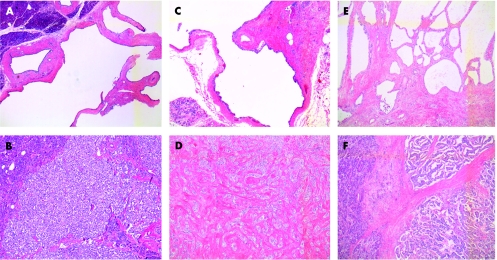

Histological examination of the pancreas showed a serous oligocystic adenoma associated with a separate endocrine tumour, without signs of malignancy (fig 1A,B). The oligocystic cystadenoma measured 1.5×2.5 cm, and was formed of three larger cysts with a few short septa branching from the wall. The endocrine tumour was a well‐defined, rounded nodule, measuring 1.1×1 cm in diameter; neither necrosis nor invasion of the pseudocapsule was noted. CD34 was assayed to highlight the vessels, which did not show neoplastic invasion. Mib1 gave a percentage of positive nuclear staining of 0–1×10 HPF, and the mitotic count was 0–1×50 HPF.

Figure 1 (A–F) Histological appearance of two components of pancreatic tumours. (A) Ill‐defined serous cystic tumour of case 1; (B) benign, well‐differentiated endocrine adenoma of case 1; (C) ill‐defined serous cystic tumour of case 2; (D) endocrine microadenoma of case 2; (E) von Hippel‐Lindau serous cystic neoplasm of case 3; (F) well‐differentiated endocrine carcinoma of case 3. All stained with haematoxylin and eosin, ×5 magnification.

Histological examination of the uterus showed multiple nodular leiomyomas of the myometrium; no other pathological findings were found in uterine specimens.

Histological examination of the kidney showed a typical oncocytoma.

Case 2

Histological examination of the pancreas showed an ill‐defined serous oligocystic adenoma measuring 2.3×2.2 cm in diameter, and a distinct endocrine microadenoma measuring 0.5 cm in diameter. No mitosis was present.

Case 3

Histological examination of the pancreas showed serous microcystic adenomas distributed throughout the head of the pancreas, ranging from 3 cm to 2 mm in diameter, associated with an endocrine carcinoma, partially within the cystic tumour and partially separated from it, infiltrating the duodenum and protruding as a polypoid mass into the ampulla of Vater (fig 1C,D). The Mib1 of the endocrine component gave a percentage of positive nuclear staining up to 15% and the mitotic count was 4×10 HPF. Vascular invasion was present and confirmed with CD34 stain. In all, 65 lymph nodes examined were negative for metastasis.

The endocrine component of all tumours stained positive for chromogranin, synaptophysin and NSE. In case 1, it was positive for glucagons, in case 2 focally positive for insulin and in case 3 positive for both glucagons and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide.

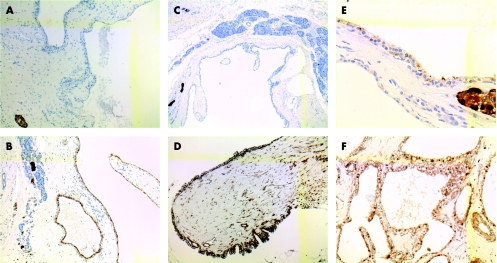

In all cases, the cells lining the cystic adenomas stained positive for PAS, were diastase‐digestible and stained positive for NSE (fig 2A–F). In only one case was focal positivity for chromogranin shown; none of the epithelial cells reacted with synaptophysin.

Figure 2 (A–F) Immunohistochemical staining for chromogranin A and neurone‐specific enolase (NSE) on the cystic component of tumours. (A) Epithelium lining cyst of case 1, staining negative for chromogranin A (chromogranin A ×10); (B) case 1, showing positive staining for NSE (NSE ×10); (C) case 2, showing same results for chromogranin A (chromogranin A ×5); (D) staining of cystic epithelial cells for NSE in case 2 (NSE ×10); (E) epithelium lining the cystic tumour in case 3, showing focal positive staining for chromogranin A (chromogranin A ×40); (F) same case 3, showing strong, diffuse staining for NSE (NSE; ×20).

None of the cases reacted with antibodies against the panel for digestive tract endocrine tumours.

Discussion

Cystic lesions in the pancreas are increasingly being discovered because of the wide use of transabdominal ultrasonography, computed tomography scanning and magnetic resonance imaging. These lesions comprise a spectrum of benign, malignant and borderline neoplasms, of which serous cystadenomas are the most frequent.10,11 More than one third of cystic lesions are discovered accidentally12 in the course of studies performed for other conditions. Management of these lesions depends on many factors, including the presence or absence of symptoms, surgical risk for the patient, type of tumour, and its location and size. The risk of malignant degeneration must be considered, particularly for mucinous cystic lesions;13 SCNs are nearly always benign, although some isolated malignant cases have been reported.14,15,16 The origin of endocrine tumours from multipotent ductular stem cells was suggested by Bordi and Bussolati in 197417 by the presence of nesidioblastosis in the ductules surrounding endocrine tumours, the origin of islets and the frequent finding of ductular cells in pancreatic endocrine tumours.16,18 Using a combination of genetic and morphological analyses, Vortmeyer et al9 also recently supported the origin of islet cell tumours from the ductal/acinar system, and concluded that the same MEN1 deletion that is characteristic for endocrine tumour tissue in MEN1‐associated pancreas can be detected in atypical cell proliferations originating in the ductal/acinar system. In contrast, the authors also reported that MEN1 deletion is consistently absent in pancreatic islet tissue. These findings strongly suggest initiation of endocrine tumorigenesis in the ductal/acinar system rather than in pancreatic islets. In a recent article, Kosmahl et al,19 studying the immunohistochemical profile of 38 SCNs, found an unusually high percentage of positivity (100%) to NSE, although the more specific endocrine antibodies, such as chromogranin and synaptophyisin, tested negative. In the same article, the authors also found a positive reaction of the epithelium lining the cysts with mucin (MUC)6.

Regarding the origin of SCNs from centroacinar pancreatic cells, Buisine et al, using in situ hybridisation,20 studied mRNA expression of mucin genes in the duodenum and accessory digestive glands such as the pancreas. They found that MUC5B and MUC6 (which is also expressed in developing centroacinar cells) are expressed in the fetal pancreas from 12 and 26 weeks of gestation, respectively, whereas MUC3 is expressed only in adult pancreas. The authors concluded that a complex spatiotemporal regulation of mucin genes probably exists, and suggested the possible regulatory role of mucin gene products in gastroduodenal epithelial cell differentiation.

von Hippel‐Lindau disease is a well‐known dominantly inherited familial cancer syndrome, patients being at high risk of developing pancreatic cysts, serous cystadenomas, pancreatic endocrine tumours and combined lesions.21 In VHL, the pancreas is involved in up to 77.2% of patients, in 12.3% by serous cystadenomas, in 12.3% by endocrine tumours and in 11.5% by combined lesions; the latter are composed of an association of serous cystic tumours and endocrine neoplasms in 6.9% of patients.22 The endocrine neoplasms in VHL are predominantly non‐functioning, or at least non‐syndromic, frequently multifocal, and with a risk of malignant transformation of up to 25%.22,23

In the past few years, six cases of combined serous cystadenoma and pancreatic endocrine tumour unrelated to VHL have been described. Table 1 shows their main clinicopathological characteristics and those of the present cases. In the reported cases, symptoms were related to the cystadenomas, as endocrine tumours never showed symptoms related to hormone hyperproduction. In one of the reported cases,5 as in two of the present cases, the pancreatic lesions were accidentally discovered during preoperative examinations for unrelated diseases, showing the same proportion in those with tumour‐related with and those without tumour‐related symptoms, as reported by Solcia et al.18

Table 1 Clinicopathological characteristics.

| Authors/year of publication | Patient's sex/age | Location of cystic tumour | Location of endocrine tumour | Endocrine tumour† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heresbach et al/1993 | F/70 | Head | Body | Well differentiated, benign |

| Keel et al/1996 | F/47 | Head | Within the cystic tumour | Well differentiated, benign |

| Kim et al/1997 | F/67 | Diffuse to entire pancreas* | Within the cystic tumour | Well differentiated, carcinoma |

| Ustun et al/2000 | F/49 | Head | Within the cystic tumour | Well differentiated, benign |

| Baek et al/2000 | F/29 | Body and tail* | Head of pancreas | Uncertain malignant potential |

| Slukvin et al/2003 | M/53 | Head | Within the cystic tumour | Well differentiated, benign |

| Alasio et al/2005 | F/78 | Body | Within the cystic tumour | Well differentiated, benign |

| Present case 1 | F/71 | Body | Body | Well differentiated, benign |

| Present case 2 | F/57 | Body | Body | Well differentiated, benign |

| Present case 3 | F/31 | Diffuse to entire pancreas* | Head | Well differentiated, carcinoma |

*Two of these cases were von Hippel‐Lindau disease‐related; the third was suspected of being associated.

†Classification of endocrine tumortumour according to World Health Organization24.

Of the 10 cases, six were circumscribed SMA, two were SOIA, and one a diffuse SMA with suspected VHL‐CN. We found another VHL‐CN associated with an endocrine tumour, reported as a single case,25 which is included as one of the cases in table 1. The site of the serous cystic tumours varied, being located in the head of the pancreas in five patients , involving the entire pancreas in one patient, located in the body and tail in three patients and in the body of the pancreas in one patient. Two patients were affected and one was suspected as having VHL.3,25

In 6 of the 10 patients the endocrine component was found within the serous cystadenoma, and in four patients it was separate. Seven cases were benign, well‐differentiated endocrine tumours, two were diagnosed as well‐differentiated endocrine carcinomas3 and one had uncertain malignant potential.25 In no case was either lymph node or liver metastasis present at the time of diagnosis.

One report5 suggests that the association of endocrine tumours with serous cystadenomas should be considered as a separate entity, although the cases in the literature show some differences.

When the data from the three present cases are included, the female:male ratio for this double pancreatic tumour is 9:1 and the median age 55.2 years. There is a female sex predilection for these double tumours, which follows that observed in serous cystadenomas, and the endocrine component seems to follow the serous component rather than behaving in a specific manner.

Comparing separately the clinical aspect of these double tumours with endocrine non‐functioning tumours, there is no sex predilection for the latter, as observed by Heitz26 and Heitz et al,27 and the mean age of incidence of the former is only slightly lower (55.2 v 58) than that of endocrine tumours from surgical series, separately considered, and much lower (55.2 v 70) than that of the same tumours when autoptical series are examined.

The serous cystic component described in association with endocrine tumours shows a lower mean age of incidence than the reported incidence of the same tumour considered singly (55.2 v 66).28,29,30,31 Reviewing the cases of combined serous cystic and endocrine tumours present in the literature and the three reported here, this association was found to be VHL‐related in 20% of cases. The mean age of occurrence of combined pancreatic tumours in VHL is much lower than that of the same VHL‐unrelated association (35 v 55.2).22,23

Considering the incidence of malignancy of the endocrine component in these associated tumours and excluding VHL‐related cases, the incidence of malignancy was found to be 20%, in contrast with that of up to 72% reported by Kent et al32 for non‐functioning endocrine tumours not incidentally found, considered separately.

On reviewing the association of related and unrelated diseases present in all 10 cases, in three cases we found diabetes mellitus (30%) and in four, a history of gallbladder stones (40%). Table 2 shows the complete list of associations found.

Table 2 Complete list of associations found.

| Authors | Associated diseases | Type of pancreatic tumour association |

|---|---|---|

| Heresbach et al | Mucinous pancreatic cystadenocarcinoma | SMA/Wwell‐differentiated, benign endocrine tumour |

| Keel et al | Systemic lupus erythematosus, with chronic steroid use | SMA/well‐differentiated benign endocrine tumour |

| Kim et al | Gallbladder stones, diabetes mellitus | Diffuse/well‐differentiated carcinoma |

| Ustun et al | Diabetes mellitus | SMA/well‐differentiated, benign endocrine tumour |

| Baek et al | VHL‐ spinal hemangioblastoma | VHL‐CN/uncertain malignant potential |

| Slukvin et al | Gallbladder stones | SMA/well‐differentiated, benign endocrine tumour |

| Alasio et al | Gallbladder stones, colonic polyposis, uterine fibroids | SMA/well‐differentiated, benign endocrine tumour |

| Present case no 1 | Uterine fibroids, left renal oncocytoma | SOIA/well‐differentiated benign endocrine tumour |

| Present case no 2 | Left adnexal adenoma, diabetes mellitus, gallbladder stones | SOIA/endocrine microadenoma |

| Present case no 3 | VHL ‐right renal cell carcinoma, left cerebellar hemangioblastoma, liver angiomas | VHL‐CN/well‐differentiated carcinoma |

SMA, serous microcystic adenoma; SOIA, serous oligocystic ill‐defined adenoma; VHL, von Hippel‐Lindau disease; VHL‐CN, von Hippel‐Lindau associated cystic neoplasm.

A review of the literature and of the present cases suggests that the association of a serous cystadenoma with an endocrine tumour of the pancreas is not probably as rare as believed previously.

At least two hypotheses may be formulated to explain this association: (1) if we believe that the endocrine component is only incidentally found, as happens for some endocrine microadenomas, then it is quite difficult to explain the close relationship between the two intermingled components, found six times in single cases reported to date in the literature; (2) these associations may all represent unrecognised VHL‐associated lesions, but the clinicopathological features are different and there is no convincing evidence.

Further studies on the molecular basis are required to establish the exact framework within which these associated pancreatic tumours must be placed, because at present there is no convincing evidence for stating that they should be considered as separate entities. The hypothesised common histogenesis of the two types of tumours also requires further study before being definitely accepted, and their true malignant potential needs to be verified in a larger series.

In conclusion, we believe that study of the pancreas for such an association of neoplasms may represent a useful model for establishing the common ductular/centroacinar origin of both types of tumours.

Abbreviations

MEN - multiple endocrine neoplasia

MUC - mucin

NSE - neurone‐specific enolase

PAS - periodic acid Schiff

SCN - serous cystic neoplasm

SMA - serous microcystic adenoma

SOIA - serous oligocystic ill‐defined adenoma

VHL - von Hippel‐Lindau disease

VHL‐CN - von Hippel‐Lindau‐associated cystic neoplasm

References

- 1.Heresbach D, Robert I, Le Berre N.et al Cystic tumors and endocrine tumor of the pancreas. An unusual association. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 199317968–971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keel S B, Zukerberg L, Graeme‐Cook F.et al A pancreatic endocrine tumor arising within a serous cystadenoma of the pancreas. Am J Surg Pathol 199620471–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim Y W, Park Y K, Lee S.et al Pancreatic endocrine tumor admixed with a diffuse microcystic adenoma—a case report. J Korean Med Sci 199712469–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ustun M O, Tugyan N, Tunakan M. Coexistence of an endocrine tumour in a serous cystadenoma (microcystic adenoma) of the pancreas, an unusual association. J Clin Pathol 200053800–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Slukvin I I, Hafez G R, Niederhuber J E.et al Combined serous microcystic adenoma and well‐differentiated endocrine pancreatic neoplasm: a case report and review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med 20031271369–1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alasio T M, Vine A, Sanchez M A.et al Pancreatic endocrine tumor coexistent with serous microcystic adenoma: report of a case and review of the literature. Ann Diagn Pathol 20059234–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Persaud V, Walrond E R. Carcinoid tumor and cystadenoma of the pancreas. Arch Pathol 19719228–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu H M, Potter E L. Development of the human pancreas. Arch Pathol 196274439–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vortmeyer A O, Huang S, Irina Lubensky I.et al Non‐islet origin of pancreatic islet cell tumors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004891934–1938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brugge W, Lauwers G, Sahani D.et al Cystic neoplasm of the pancreas. N Engl J Med 20043511218–1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kloppel G, Solcia E, Longnecker D S.et alHistological typing of tumours of the exocrine pancreas: World Health Organization international histological classification of tumours. 2nd edn. Springer, Berlin: Springer, 1996

- 12.Fernandez‐del Castillo C, Targarona J, Thayer S P.et al Incidental pancreatic cysts: clinicopathologic characteristic and comparison with symptomatic patients. Arch Surg 2003138427–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilentz R E, Albores‐Saavedra J, Zahurak M.et al Pathologic examination accurately predicts prognosis in mucinous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. Am J Surg Pathol 1999231320–1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.George D H, Murphy F, Michalski R.et al Serous cystadenocarcinoma of the pancreas: a new entity? Am J Surg Pathol 19891361–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kamei K, Funabiki T, Ochiai M.et al Multifocal pancreatic serous cystadenoma with atypical cells and focal perineural invasion. Int J Pancreatol 199110161–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoshimi N, Sugie S, Tanaka T.et al A rare case of serous cystadenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Cancer 1992692449–2453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bordi C, Bussolati G. Immunofluorescence, histochemical and ultrastructural studies for the detection of multiple endocrine polypeptide tumours of the pancreas. Virchows Arch B Cell Pathol 19741713–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Solcia E, Sessa F, Rindi G.et al Pancreatic endocrine tumors: general concepts; non‐functioning tumors and tumors with uncommon function. In: Dayal Y, ed. Endocrine pathology of the gut and pancreas. Boca Raton: CRC Press, 1991105–131.

- 19.Kosmahl M, Wagner J, Peters K.et al Serous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. An immunohistochemical analysis revealing alpha‐inhibin, neuron‐specific enolase, and MUC6 as new markers. Am J Surg Pathol 200428339–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buisine M P, Devisme L, Degand P.et al Developmental mucin gene expression in the gastroduodenal tract and accessory digestive glands. II. Duodenum and liver, gallbladder, and pancreas. J Histochem Cytochem 2000481667–1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lubensky I A, Pack S, Ault D.et al Multiple neuroendocrine tumors of the pancreas in von Hippel‐Lindau disease patients: histopathological and molecular genetic analysis. Am J Pathol 1998153223–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hammel P R, Vilgrain V, Terris B.et al Pancreatic involvement in von Hippel‐Lindau disease. The Groupe Francophone d'Etude de la Maladie de von Hippel‐Lindau. Gastroenterology 20001191087–1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Libutti S K, Choyke P L, Alexander H R.et al Clinical and genetic analysis of patients with pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors associated with von Hippel‐Lindau disease. Surgery 20001281022–1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Solcia E, Kloppel G, Sobin L H. eds. Histological typing of endocrine tumours. 2nd edn. Berlin: Springer Verlag, 2000

- 25.Baek S Y, Kang B C, Choi H Y.et al Pancreatic serous cystadenoma associated with islet cell tumour. Br J Radiol 20007383–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heitz P U. Pancreatic endocrine tumours. In: Kloppel G, Heitz PU, eds. Pancreatic pathology. Edinburgh: Churchill‐Livingstone, 1984206–232.

- 27.Heitz P U, Kasper M, Polak J M.et al Pancreatic endocrine tumors. Hum Pathol 198213263–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamaguchi K, Enjoji M. Cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. Gastroenterology 1987921934–1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alpert L C, Truong L D, Bossart M I.et al Microcystic adenoma (serous cystadenoma) of the pancreas. A study of 14 cases with immunohistochemical and electron microscopic correlation. Am J Surg Pathol 198812251–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Warshaw A L, Compton C C, Lewandrowsky K.et al Cystic tumors of the pancreas. New clinical, radiologic, and pathologic observations in 67 patients. Ann Surg 1990212432–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Egawa N, Maillet B, Schroder S.et al Serous oligocystic and ill‐demarcated adenoma of the pancreas: a variant of serous cystic adenoma. Virchows Arch 199442413–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kent R B, van Heerden J A, Weiland R H. Nonfunctioning islet cell tumors. Ann Surg 1981193185–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]