Abstract

A unique case of prostatic stromal sarcoma (PSS) that recurred in the pelvic cavity with massive high‐grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia is described. A 52‐year‐old man who presented with urinary retention underwent a radical cystoprostatectomy. Tumour tissues of the prostate showed an admixture of hyperplastic glands and markedly cellular stroma of spindle cells arranged in a fascicular pattern, and the tumour was diagnosed as PSS. 66 months after the operation, CT scans revealed three recurrent tumours around the bilateral obturator and left fore iliopsoas. The recurrent tumours were biphasic neoplasms, as before, but the epithelial component had grown prominent and manifested overt atypia in a manner resembling high‐grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia. Our findings suggest that not only the stromal component but also and the epithelial components of PSS may have malignant potential.

Mixed epithelial–stromal tumour of the prostate is a rare lesion composed of spindle to pleomorphic stromal cells and an intervening benign glandular element.1,2 In 1998, Gaudin et al classified sarcomas and related proliferative lesions of the specialised prostatic stroma, including prostatic phyllodes tumours, into two categories: prostatic stromal sarcoma (PSS) and prostatic stromal proliferation of uncertain malignant potential.1,3 PSS and prostatic stromal proliferation of uncertain malignant potential often recur with increasing atypia of neoplastic stromal cells, especially after incomplete resection.1,2,4,5,6,7,8,9 Less attention has been focused on the epithelial component of these tumours, a component that has been consistently considered non‐neoplastic.1 Here, we report a case of extraprostatic recurrent PSS in which the epithelial component represented massive high‐grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (HGPIN).

Case history

A 52‐year‐old man presented with urinary retention. Digital rectal examination revealed a markedly enlarged prostate with soft consistency. The serum prostate‐specific antigen (PSA) level was 7.25 ng/ml (normal: <4 ng/ml). CT showed a 7 cm mass in the posterior prostate, with some compression of both the bladder and rectum. A needle biopsy specimen was histologically diagnosed as prostatic sarcoma. The patient underwent a radical cystoprostatectomy and ileal conduit construction without a pelvic lymphadenectomy. The serum PSA fell to <0.1 ng/ml after the operation.

CT performed 66 months after the operation revealed three recurrent tumours around the bilateral obturator and left fore iliopsoas (fig 1). Serum PSA had risen to 3.3 ng/ml. The patient was diagnosed with recurrent prostatic sarcoma and treated with a combination chemotherapy (three cycles of cisplatin, pirarubicin and ifosfamide). The recurrent tumours were resected and the patient was discharged. The serum PSA fell to 0.2 ng/ml after the second operation; however, 12 months after the operation, the serum PSA rose again to 3.7 ng/ml and CT revealed a 4 cm recurrent tumour around the right obturator.

Figure 1 CT scans shows two recurrent tumours (*) around the bilateral psoas major muscles.

Methods

Gross examination of the cystoprostatectomy specimen revealed a cavity in the posterior prostate from which the soft tumour material had flowed out during the operation. A fragmented, soft and greyish tumour was submitted separately. The recurrent tumours consisted of fragments of soft, grey to brown tissue. Whole portions of both of the primary and recurrent tumours were embedded in paraffin wax and examined histologically.

Immunostaining of formalin‐fixed paraffin‐wax‐embedded sections of the tissue was performed by the labelled streptavidin using biotin method with an LSAB2 kit (DacoCytomation, Carpinteria, California, USA) and the following antibodies: PSA (polyclonal, DakoCytomation; prediluted), Ki‐67 (MIB‐1, Immunotech, Marseille, France; 1:200 dilution), high‐molecular‐weight cytokeratin (HMWCK) (34βE12, DakoCytomation; 1:100 dilution) and α‐methylacyl‐coenzyme A racemase (AMACR) (polyclonal, Diagnostic Biosystems, Pleasanton, California, USA; 1:100 dilution).

Results

Primary tumour

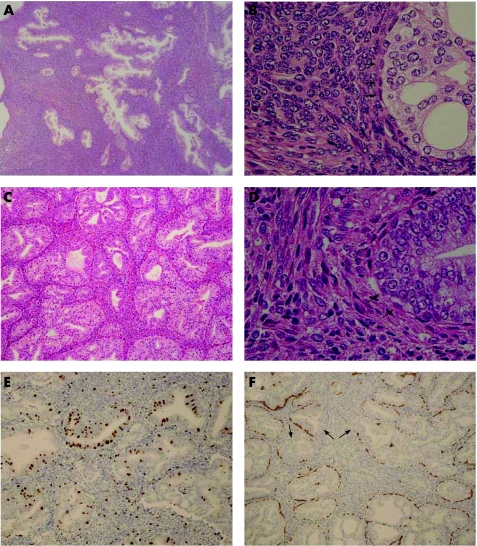

Microscopically, the tumour was biphasic, with markedly cellular stroma interspersed with glands (fig 2A). The ratio between the epithelial and stromal components (E:S ratio) was about 1:4. The glands appeared hyperplastic, and no slit‐like phyllodes pattern was apparent. Cribriform glands were also sporadically observed. The secretory cells had uniformly enlarged nuclei with inconspicuous nucleoli, with a lining of single‐layered basal cells (fig 2B). A few glands manifested squamous metaplasia. The stroma was markedly cellular with spindle cells arranged in a fascicular pattern. The tumour was diagnosed as PSS based on the marked stromal cellularity and scattered mitotic figures (4 mitoses per 10 high‐power fields).

Figure 2 (A,B) Histological findings of the primary tumour. (A) Admixture of glands and highly cellular stroma. (B) Cribriform glands were sporadically observed. The secretory cells have uniformly enlarged nuclei and inconspicuous nucleoli, with a lining of single‐layered basal cells (arrowheads). (C,D) Histological findings of the recurrent tumour. (C) Admixture of glands and cellular stroma; the former is predominant and cribriform glands were frequently observed. (D) The secretory cells are densely stratified and have prominent nucleoli, with a lining of single‐layered basal cells (arrowheads). (E,F) Immunostaining in the recurrent tumour. (E) More Ki‐67 immunoreactive nuclei are observed in the epithelia than in the stroma. (F) Immunostaining for high‐molecular‐weight cytokeratin demonstrates a partly discontinuous pattern of basal cell reactivity (arrowheads).

Recurrent tumours

Microscopically, the tumours were biphasic, as before, with an admixture of glands and cellular stroma (fig 2C). In contrast to the primary tumour, however, the glandular component was predominant (the E:S ratio was about 3:2). Cribriform glands were frequently observed. Moreover, the epithelial cells exhibited a diffuse pattern of prominent atypia with dense stratification and prominent nucleoli (fig 2D). A distinct layer of basal cells still remained, although often obscurely. The stromal component, on the other had, closely resembled that of the primary tumour with some degeneration. No lymph node examined was involved by the tumour.

Immunohistochemistry

The epithelial cells of both primary and recurrent tumours were diffusely immunoreactive for PSA. Three of the findings in the epithelia differed considerably between the primary tumour and recurrent tumours, however: (1) a marked increase of the Ki‐67 labelling index from 1.2% in the primary tumour to 17.1% in the recurrent tumour (fig 2E); (2) a discontinuous pattern of basal cell layer in HMWCK staining of the recurrent tumours (fig 2F) versus continuous staining in the primary tumour; (3) a weak immunoreactivity for AMACR in the recurrent tumours versus no immunoreactivity in the primary tumour.

Discussion

In the present case, the whole epithelia in the recurrent tumours manifested prominent structural and nuclear atypia suggestive of HGPIN. The following immunohistochemical results in the epithelia of the recurrent tumours were compatible with HGPIN: (1) markedly higher levels of Ki‐67 labelling index (which rises higher in prostatic adenocarcinoma and HGPIN than in benign glands10,11) in the epithelia; (2) discontinuous staining for HMWCK (a staining pattern typical of HGPIN12); (3) weak staining for AMACR (which stains the majority of prostatic adenocarcinoma and HGPIN13). The malignant transformation of the epithelia surrounded by malignant stromal cells implies the existence of an epithelial–stromal interaction—that is, an aberrant stromal microenvironment promoted malignant transformation of the epithelia.14

Take‐home message

Prostatic stromal sarcoma is not simply a stromal neoplasm as previously believed. Not only the stromal component but also the epithelial component may have a malignant potential.

Another remarkable finding in the present case was that basal cells, in addition to atypical stromal and secretory cells, existed in multiple recurrent tumours outside the prostate. Although a recent molecular genetic study has demonstrated that both epithelial and stromal components of prostatic phyllodes tumours are clonal,15 the clonality of basal cells in prostatic stromal tumours has not been examined. In a previous study, McCarthy et al concluded that epithelial and stromal components might have different clonal origins.15 Contrary to McCarthy et al's study, our finding raises the possibility that both components, including basal cells, have a common clonal origin.

In summary, we report a previously unreported case of extraprostatic recurrent PSS in which the epithelial component represented massive HGPIN. It is important to note that mixed epithelial–stromal tumour of the prostate is not solely a stromal neoplasm as previously believed, and that not only the stromal but also the epithelial component of this tumour may have a malignant potential.

Abbreviations

AMACR - α‐methylacyl‐coenzyme A racemase

HGPIN - high‐grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia

PSA - prostate‐specific antigen

PSS - prostatic stromal sarcoma

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Gaudin P B, Rosai J, Epstein J I. Sarcomas and related proliferative lesions of specialized prostatic stroma: a clinicopathologic study of 22 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 199822148–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bostwick D G, Hossain D, Qian J.et al Phyllodes tumor of the prostate: long‐term followup study of 23 cases. J Urol 2004172894–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheville J, Cheng L, Algaba F.et al Mesenchymal tumours. In: Eble JN, Sauter G, Epstein JI, et al eds. Pathology and genetics of tumours of the urinary system and male genital organs. Lyon, France: IARC Press, 2004209–211.

- 4.Lopez‐Beltran A, Gaeta J F, Huben R.et al Malignant phyllodes tumor of prostate. Urology 199035164–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yum M, Miller J C, Agrawal B L. Leiomyosarcoma arising in atypical fibromuscular hyperplasia (phyllodes tumor) of the prostate with distant metastasis. Cancer 199168910–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Young J F, Jensen P E, Wiley C A. Malignant phyllodes tumor of the prostate. A case report with immunohistochemical and ultrastructural studies. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1992116296–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watanabe M, Yamada Y, Kato H.et al Malignant phyllodes tumor of the prostate: retrospective review of specimens obtained by sequential transurethral resection. Pathol Int 200252777–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agrawal V, Sharma D, Wadhwa N. Case report: malignant phyllodes tumor of prostate. Int Urol Nephrol 20033537–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen T A, Chou J M, Sun G H.et al Malignant phyllodes tumor of the prostate. Int J Urol 2005121007–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tamboli P, Amin M B, Schultz D S.et al Comparative analysis of the nuclear proliferative index (Ki‐67) in benign prostate, prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia, and prostatic carcinoma. Mod Pathol 199691015–1019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haussler O, Epstein J I, Amin M B.et al Cell proliferation, apoptosis, oncogene, and tumor suppressor gene status in adenosis with comparison to benign prostatic hyperplasia, prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia, and cancer. Hum Pathol 1999301077–1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bostwick D G, Brawer M K. Prostatic intra‐epithelial neoplasia and early invasion in prostate cancer. Cancer 198759788–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang Z, Woda B A, Wu C L.et al Discovery and clinical application of a novel prostate cancer marker: alpha‐methylacyl CoA racemase (P504S). Am J Clin Pathol 2004122275–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cunha G R, Hayward S W, Wang Y Z. Role of stroma in carcinogenesis of the prostate. Differentiation 200270473–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCarthy R P, Zhang S, Bostwick D G.et al Molecular genetic evidence for different clonal origins of epithelial and stromal components of phyllodes tumor of the prostate. Am J Pathol 20041651395–1400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]