We read with interest the paper by Granito et al1 reporting on the clinical and diagnostic significance of anti‐filamentous actin antibodies (A‐FAA) in autoimmune hepatitis type 1 (AIH‐1). The authors found that A‐FAA, measured by a new commercially available ELISA based on a modified cut‐off of 30 instead of the manufacturer's 20 arbitary units (AU), strictly correlates with the smooth muscle antibody glomerular/tubular (SMA‐G/T) pattern,2 also known as the microfilament pattern, mostly seen in patients with AIH‐1.1 Their findings further indicate F‐actin as the predominant, if not the sole, target of AIH‐1‐specific SMA reactivity, a notion that has been questioned in the past because of the inconsistent results obtained by several actin‐based assays.3,4

We agree with Granito et al1 that many laboratories are unfamiliar with the interpretation of the immunofluorescence patterns of AIH‐specific SMA; such a problem arguably generates an urgent need for a reliable and observer‐independent molecular‐based SMA detection assay.5 New commercially available A‐FAA ELISAs could be viable alternatives for routine laboratories, as the likelihood of a false‐negative result is relatively low, but the possibility of reporting inaccurate results by immunofluorescence remains high.

We would like to raise a few points on the basis of our recent experience with the A‐FAA ELISA.

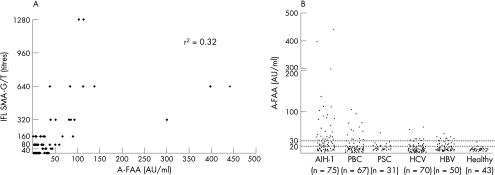

At variance with Granito et al1—and using the same ELISA and modified cut‐off of 30 AU—we found A‐FAA seropositivity in a considerable proportion of SMA‐G/T‐seronegative patients with AIH‐1 (fig 1A). The increased sensitivity of the A‐FAA ELISA comes to the cost of its lower specificity, as it detects A‐FAA in a considerable number of SMA‐seronegative pathological controls, especially in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis and chronic hepatitis C (fig 1B).

Figure 1 (A) Scatter plot representation of the correlation between the ELISA titres (arbitary units, AU) of the anti‐filamentous actin antibodies (A‐FAA; x axis) and the titres of smooth muscle antibody glomerular/tubular (SMA‐G/T) pattern by indirect immunofluorescence (IFL; y axis). (B) ELISA titres for A‐FAA in 75 patients with autoimmune hepatitis type 1 (AIH‐1), 67 with primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC), 31 with primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), 70 with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, 50 with hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection and 43 healthy controls. According to the manufacturer's instructions, a test is strong positive when the ELISA titre is >30 AU; weak positive between 20 and 30 AU; and negative at <20 AU. In agreement with Granito et al,1 the mean (standard deviation) optical density at 450(5) nm in our 50 controls corresponds to 29.6 AU.

We also found through inhibition studies that AIH‐1‐specific SMA‐G/T reactivity is not always abolished by F‐actin as a solid‐phase competitor; only in one of the three patients with AIH‐1 were we able to absorb out immunofluorescence SMA‐G/T reactivity by 70% using F‐actin as a solid‐phase competitor6,7 (in the other two patients, SMA‐G/T reactivity was inhibited by 23% and 47%).

Our inhibition studies suggest that F‐actin is a likely, but not the only, target of AIH‐specific SMA reactivity.5 We agree with the recent consensus statement of the international autoimmune hepatitis group affirming that: (1) the basic technique of choice at present for the routine testing of SMA patterns relevant to AIH is indirect immunofluorescence on a rodent multiorgan (kidney, liver and stomach) substrate and (2) the remaining targets of the AIH‐1‐specific microfilament reactivity will require further identification.5 We also think that larger studies are needed to consider the performance of the newly established A‐FAA ELISA in terms of specificity and sensitivity.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Paul Cheeseman for his help with the artwork.

Footnotes

Funding: This work has been supported in part by a grant (Code Number 2466) of the Research Committee of the University of Thessaly (Code Number 2466).

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Granito A, Muratori L, Muratori P.et al Antibodies to filamentous actin (F‐actin) in type 1 autoimmune hepatitis. J Clin Pathol 200659280–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bottazzo G F, Florin‐Christensen A, Fairfax A.et al Classification of smooth muscle autoantibodies detected by immunofluorescence. J Clin Pathol 197629403–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bretherton L, Brown C, Pedersen J S.et al ELISA assay for IgG autoantibody to G‐actin: comparison of chronic active hepatitis and acute viral hepatitis. Clin Exp Immunol 198351611–616. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leibovitch L, George J, Levi Y.et al Anti‐actin antibodies in sera from patients with autoimmune liver diseases and patients with carcinomas by ELISA. Immunol Lett 199548129–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vergani D, Alvarez F, Bianchi F B.et al Liver autoimmune serology: a consensus statement from the committee for autoimmune serology of the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group. J Hepatol 200441677–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bogdanos D P, Baum H, Gunsar F.et al Extensive homology between the major immunodominant mitochondrial antigen in primary biliary cirrhosis and Helicobacter pylori does not lead to immunological cross‐reactivity. Scand J Gastroenterol 200439981–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bogdanos D P, Baum H, Okamoto M.et al Primary biliary cirrhosis is characterized by IgG3 antibodies cross‐reactive with the major mitochondrial autoepitope and its Lactobacillus mimic. Hepatology 200542458–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]