Abstract

Objectives

To investigate whether sildenafil citrate, a selective phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor, may improve endothelial vasomotor and fibrinolytic function in patients with coronary heart disease.

Design

Randomised double blind placebo controlled crossover study.

Patients and methods

16 male patients with coronary heart disease and eight matched healthy men received intravenous sildenafil or placebo. Bilateral forearm blood flow and fibrinolytic parameters were measured by venous occlusion plethysmography and blood sampling in response to intrabrachial infusions of acetylcholine, substance P, sodium nitroprusside, and verapamil.

Main outcome measures

Forearm blood flow and acute release of tissue plasminogen activator.

Results

Mean arterial blood pressure fell during sildenafil infusion from a mean (SEM) of 92 (1) to 82 (1) mm Hg in patients and from 94 (1) to 82 (1) mm Hg in controls (p < 0.001 for both). Sildenafil increased endothelium independent vasodilatation with sodium nitroprusside (p < 0.05) but did not alter the blood flow response to acetylcholine or verapamil in patients or controls. Substance P caused a dose dependent increase in plasma tissue plasminogen activator antigen concentrations (p < 0.01) that was unaffected by sildenafil in either group.

Conclusions

Sildenafil does not improve peripheral endothelium dependent vasomotor or fibrinolytic function in patients with coronary heart disease. Phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors are unlikely to reverse the generalised vascular dysfunction seen in patients with coronary heart disease.

Keywords: coronary heart disease, endothelium, fibrinolysis, forearm blood flow, nitric oxide

The endothelium is important in the regulation of vascular function including local blood flow and endogenous fibrinolysis. Coronary heart disease (CHD) and its risk factors, such as cigarette smoking, hyperlipidaemia, and hypertension,1,2,3 are associated with impaired endothelium dependent vasorelaxation and reduced endothelial release of the endogenous fibrinolytic factor tissue plasminogen activator (t‐PA).4,5 These aspects of endothelial function are important, since plasma fibrinolytic variables and endothelium dependent vasodilatation independently predict future cardiovascular risk.6,7

Nitric oxide is a key factor linked to the beneficial protective effects of the endothelium and a decrease in nitric oxide bioavailability favours atherogenesis.8 Nitric oxide exerts many of its biological effects through generation of cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) after activation of soluble guanylate cyclase. Phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5) inactivates cGMP within vascular smooth muscle and thus negatively regulates nitric oxide mediated cellular actions.9 Recently, highly selective PDE5 inhibitors that prolong the action of cGMP and thereby enhance nitric oxide mediated effects have become available for clinical use.

It has been suggested that the PDE5 inhibitor sildenafil citrate (Viagra; Pfizer) can improve endothelial vasomotor function in the peripheral circulation of healthy cigarette smokers10 and the coronary circulation of patients with CHD.11 Although we have previously reported a link between nitric oxide and acute t‐PA release,12 the potential beneficial effects of sildenafil on t‐PA and its inhibitor, plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 (PAI‐1), are unknown.

We therefore hypothesised that sildenafil would favourably alter endothelium dependent vasomotor function and acute t‐PA release in patients with stable CHD. If so, PDE5 inhibitors may become a useful adjunctive treatment and confer secondary preventative benefits on patients with CHD.

METHODS

Patients

Sixteen male patients with stable CHD and eight age matched healthy control men participated in the study. The investigation was undertaken with the approval of the local research ethics committee, with the written informed consent of each patient, and in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

A history of CHD was confirmed by angiographic evidence of > 50% luminal stenosis of at least one major epicardial coronary vessel or a history of myocardial infarction (confirmed by a serial rise in creatine kinase of twice the upper limit of the normal reference range and the development of pathological Q waves in at least two contiguous leads of the ECG). Nitrate medications were withdrawn for 48 hours before each visit and other medications were withheld on the morning of study. Patient exclusion criteria were significant cardiac failure, renal impairment, systolic blood pressure < 100 or > 190 mm Hg, and diabetes mellitus. Control subjects were healthy normotensive euglycaemic non‐smokers without any history of cardiorespiratory or vascular disease and were not taking any regular medications. No participant had received sildenafil or other phosphodiesterase inhibitors before or during participation in this study.

Measurements

Forearm blood flow (FBF) was measured in both forearms by venous occlusion plethysmography with mercury in silastic strain gauges applied to the widest part of the forearm as previously described.12,13,14 During measurement periods the hands were excluded from the circulation by rapid inflation of the wrist cuffs to a pressure of 220 mm Hg with E20 rapid cuff inflators (DE Hokanson Inc, Bellevue, Washington, USA). Upper arm cuffs were inflated intermittently to 40 mm Hg for 10 seconds in every 15 seconds to achieve venous occlusion and obtain plethysmographic recordings. Analogue voltage output from an EC‐4 strain gauge plethysmograph (DE Hokanson) was processed by an analogue to digital converter and Chart version 5 software (AD Instruments Ltd, Chalgrove, UK). Instruments were calibrated with the internal standard of the plethysmograph. Blood pressure and heart rate were monitored in the non‐infused arm by a semiautomated non‐invasive sphygmomanometer (Agilent V24; Phillips Medical Systems). Mean arterial pressure was defined as the diastolic pressure plus a third of the pulse pressure.

Plasma t‐PA and PAI‐1 antigen concentrations were measured as previously described with enzyme linked immunosorbent assays (Coaliza t‐PA and PAI‐1; Chromogenix AB, Mölndal, Sweden) at baseline, after sildenafil or placebo, and during intra‐arterial substance P.4,12,14 Haematocrit was determined by an automated Coulter counter (ACt.8; Beckman‐Coulter, High Wycombe, UK). Biochemical assays were undertaken on the fasting venous samples by the hospital clinical laboratory facility.

Study design

Participants were requested to abstain from alcohol for 24 hours and from food, caffeine‐containing drinks, and tobacco for at least four hours before each study. All studies were carried out in a quiet temperature controlled room maintained at 22–25°C. Each participant attended at 9 am on two separate occasions at least two weeks apart and received matched placebo and sildenafil in a randomised double blind crossover design.

While participants rested recumbent, strain gauges and cuffs were applied. A 17 gauge venous cannula was inserted into the antecubital vein of each arm and a 23 gauge cannula into the dorsal foot vein for the administration of either intravenous sildenafil or matched placebo. The brachial artery of the non‐dominant arm was cannulated with a 27‐SWG needle (Cooper's Needle Works Ltd, Birmingham, UK) under local anaesthesia. The intra‐arterial infusion rate was maintained constant at 1 ml/min throughout the study with an IVAC syringe pump (Alaris Medical Ltd, Basingstoke, UK).

Saline was infused intra‐arterially for the first 20 minutes to allow recording of resting FBF, blood pressure, and heart rate. After this period, sildenafil or matched placebo (Pfizer UK Ltd, Sandwich, Kent, UK) was administered intravenously as a single 26.25 mg bolus over five minutes, then as a continuous infusion of 10 mg/hour to achieve stable plasma concentrations equivalent to the peak concentration of a single 100 mg oral dose (pharmacokinetic data, Pfizer UK Ltd). Twenty minutes after the sildenafil or placebo infusion was started, basal FBF was determined and thereafter acetylcholine (5, 10, and 20 μg/min; Novartis UK Ltd, Farnborough, UK), substance P (2, 4, and 8 pmol/min; Clinalfa AG, Läufelfingen, Switzerland), sodium nitroprusside (2, 4, and 8 μg/min; David Bull Laboratories, Warwick, UK), and verapamil (10, 30, and 100 μg/min; Abbott UK Ltd) were infused intra‐arterially for six minutes at each dose. Acetylcholine, substance P, and sodium nitroprusside were given in a random order and separated by 20 minute saline washout periods but, because of its prolonged vasodilator action, verapamil was infused last. The order of the infusions was maintained constant for each participant across both visits.

Statistical analysis

Plethysmographic data were extracted from Chart data files from which the last five linear recording in each measurement period were averaged and FBF was calculated. Estimated net t‐PA antigen was defined as the product of the infused forearm plasma flow (based on the haematocrit and the infused FBF) and the concentration difference between the infused ([t‐PA]inf) and non‐infused ([t‐PA]Non‐inf) forearms,12,14 where estimated net t‐PA release = FBF×(1−haematocrit)×([t‐PA]inf) −([t‐PA]Non‐inf).

Data were examined, where appropriate, by analysis of variance with repeated measures and two tailed Student's t test by GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California, USA). All results are expressed as mean (SEM). Significance was assigned at the 5% level. On the basis of a previous study,15 this study had an 80% power to detect a 23% change in plasma t‐PA concentrations and a 22% difference in FBF in patients with CHD between sildenafil and placebo at the 5% level.

RESULTS

Most patients with CHD had a history of myocardial infarction, hypertension, and hyperlipidaemia (table 1). Reflecting concomitant treatment, mean resting heart rate (55 (1) v 63 (2) beats/min, respectively, p < 0.001, unpaired t test) and serum total cholesterol concentration (4.2 (0.2) v 5.5 (0.2) mmol/l, p < 0.001) were lower in patients with CHD than in controls. Baseline mean arterial pressure, resting heart rate, baseline FBF, or haematocrit did not differ between the two study visits. Infusions were well tolerated and there were no serious adverse events. For technical reasons, one control subject was unable to complete both visits.

Table 1 Baseline characteristics.

| Patients | Controls | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 57 (2) | 54 (2) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 27 (1) | 27 (1) |

| Co‐morbidity | ||

| Myocardial infarction | 10 | 0 |

| Hypertension | 12 | 0 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0 | 0 |

| Previous hyperlipidaemia | 15 | 0 |

| Smoker/non‐smoker | 1/15 | 0/8 |

| Medications | ||

| Aspirin | 16 | 0 |

| β Adrenergic blocker | 13 | 0 |

| Calcium antagonist | 3 | 0 |

| Long acting nitrate/nicorandil | 2 | 0 |

| ACE inhibitor, AT II antagonist | 5 | 0 |

| Lipid lowering agent | 16 | 0 |

| Serum urea (mmol/l) | 5.5 (0.3) | 5.1 (0.4) |

| Serum creatinine (μmol/l) | 92 (3) | 95 (4) |

| Glucose (mmol/l) | 5.6 (0.2) | 5.5 (0.3) |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/l) | 4.2 (0.2) | 5.5 (0.2)* |

| HDL cholesterol (mmol/l) | 1.0 (0.0) | 1.1 (0.1) |

| Triglycerides (mmol/l) | 1.7 (0.2) | 1.2 (0.2) |

| Placebo visit | ||

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 55 (1) | 61 (3)* |

| MAP (mm Hg) | 95 (2) | 95 (4) |

| FBF (ml/100 ml/min) | ||

| Infused arm | 2.5 (0.2) | 2.2 (0.2) |

| Non‐infused arm | 2.3 (0.2) | 2.1 (0.4) |

| Sildenafil visit | ||

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 55 (1) | 65 (3)* |

| MAP (mm Hg) | 95 (2) | 91 (3) |

| FBF (ml/100 ml/min) | ||

| Infused arm | 2.5 (0.2) | 2.6 (0.3) |

| Non‐infused arm | 2.5 (0.2) | 2.4 (0.3) |

Data are mean (SEM) or number.

*p<0.001 unpaired t test, patients v controls.

ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme; AT II, angiotensin II type I receptor; FBF, forearm blood flow; HDL, high density lipoprotein; MAP, mean arterial pressure.

Haemodynamic effects

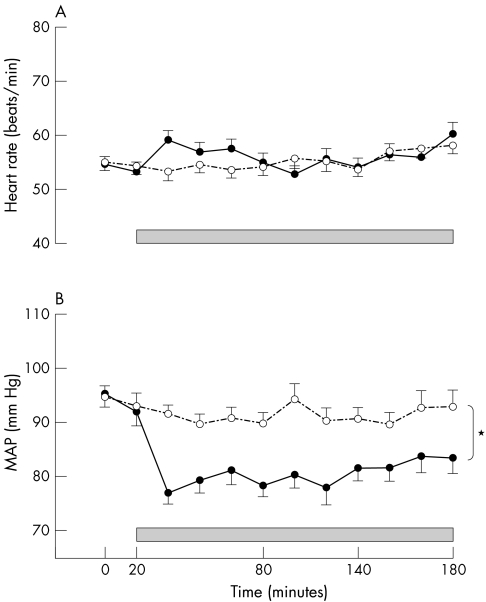

Over the course of the study, the average mean arterial pressure was lower during sildenafil than placebo infusion in patients with CHD (82 (1) v 92 (1) mm Hg, p < 0.001 paired t test sildenafil versus placebo) (fig 1) and control subjects (82 (1) v 94 (1) mm Hg, p < 0.001 paired t test). It returned to baseline after discontinuation of infusion (data not shown). Heart rate rose transiently after the sildenafil bolus in both groups (fig 1 and data on file).

Figure 1 (A) Heart rate and (B) mean arterial pressure (MAP) during sildenafil (closed circles, solid line) or placebo (open circles, dashed line) infusion (shaded box) in patients with coronary heart disease (CHD). *p < 0.001 analysis of variance, sildenafil versus matched placebo. Control subject data on file (p < 0.001, analysis of variance, MAP sildenafil versus matched placebo).

Placebo visit

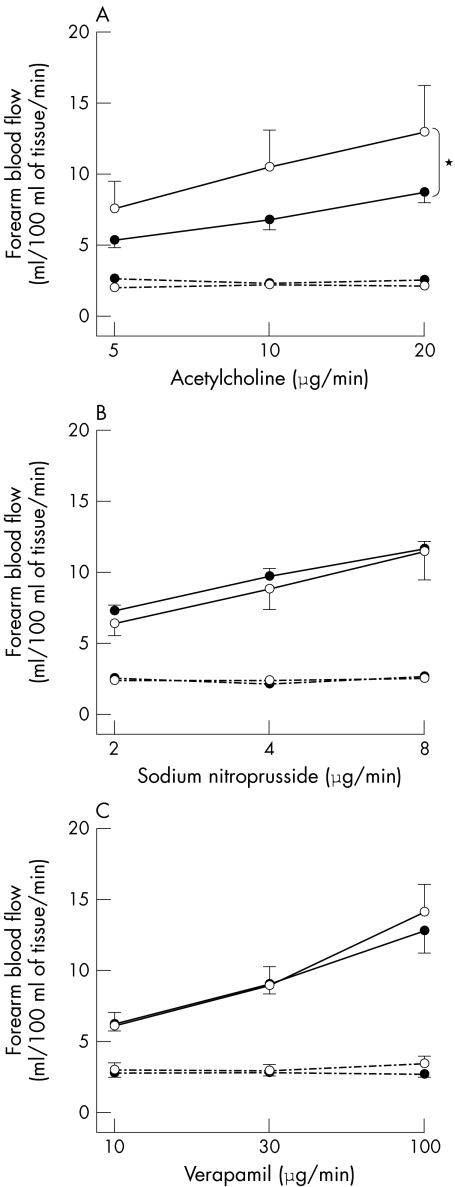

Acetylcholine caused a dose dependent increase in FBF in both groups, although this rise was significantly less in patients with CHD than in controls (p = 0.005, analysis of variance) (fig 2). FBF responses did not differ between the two groups during sodium nitroprusside and verapamil infusions (fig 2). There were no significant changes in the non‐infused FBF.

Figure 2 Infused (solid line) and non‐infused (dashed line) forearm blood flow in patients with CHD (•) and controls (○) during intrabrachial acetylcholine (panel A), sodium nitroprusside (panel B), and verapamil (panel C) with placebo infusion. p < 0.001 analysis of variance, dose response in infused arm; *p = 0.005 analysis of variance patients with CHD versus controls.

Sildenafil and vascular function

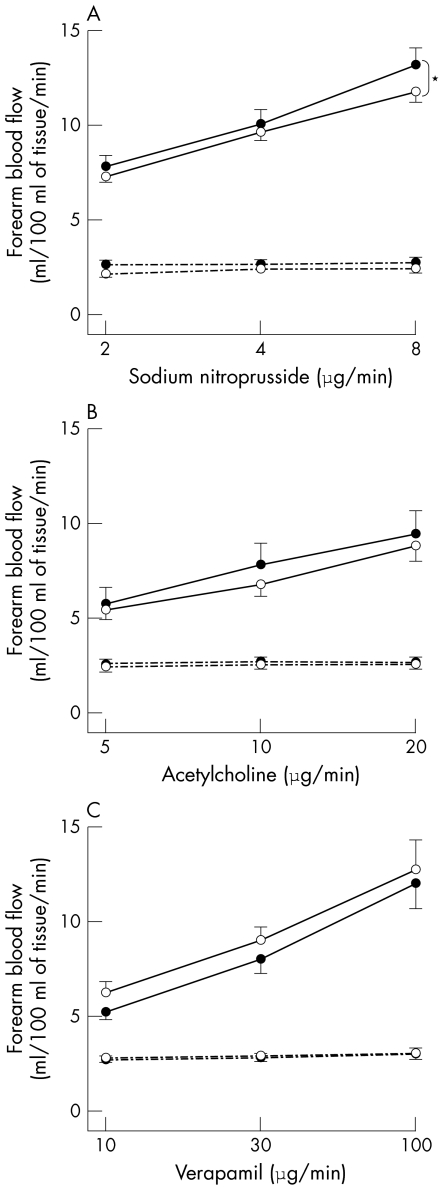

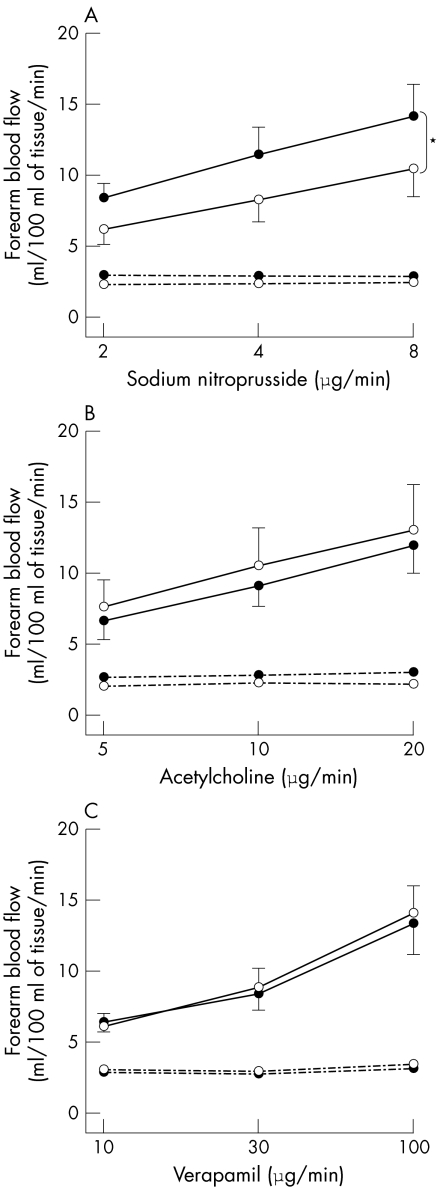

Compared with placebo, administration of sildenafil caused no significant difference in the infused FBF during intra‐arterial infusion of acetylcholine (at 20 μg/min, mean difference 0.1 ml/100 ml/min, 95% confidence interval (CI) −0.2 to 0.4), substance P (at 8 pmol/min, mean difference 0.5 ml/100 ml/min, 95% CI 0.00 to 0.9), or verapamil (at 8 pmol/min, mean difference 0.3 ml/100 ml/min, 95% CI −0.1 to 0.7). However, sildenafil augmented the vasodilatation to sodium nitroprusside in both patients with CHD (p < 0.05, analysis of variance) (fig 3) and control subjects (p < 0.001, analysis of variance) (fig 4).

Figure 3 Infused (solid line) and non‐infused (dashed line) forearm blood flow in patients with CHD during intrabrachial sodium nitroprusside (panel A), acetylcholine (panel B), and verapamil (panel C) with sildenafil (•) and matched placebo (○) infusion. p < 0.001 analysis of variance, dose response in infused arm; *p < 0.05 analysis of variance, sildenafil versus matched placebo.

Figure 4 Infused (solid line) and non‐infused (dashed line) forearm blood flow in healthy controls during intrabrachial sodium nitroprusside (panel A), acetylcholine (panel B), and verapamil (panel C) with sildenafil (•) and matched placebo (○) infusion. p ⩽ 0.01 analysis of variance, dose response in infused arm; *p < 0.001 analysis of variance, sildenafil versus matched placebo.

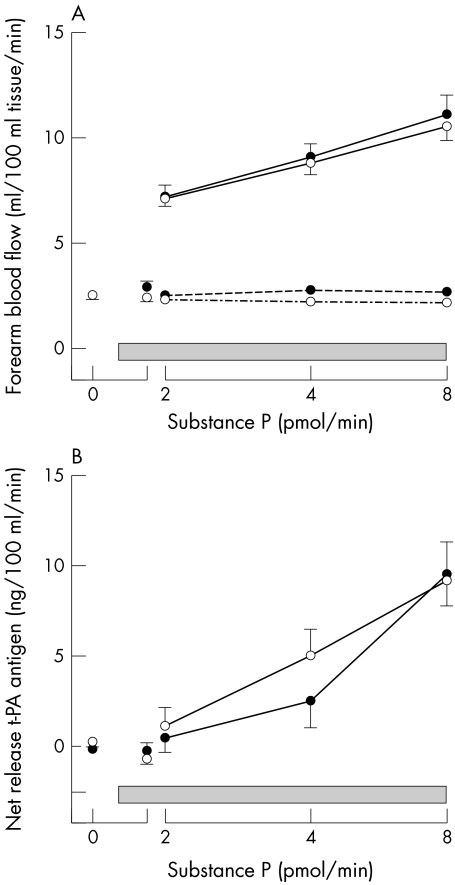

Plasma fibrinolytic variables

Baseline plasma t‐PA antigen concentrations were unchanged by sildenafil in either group (table 2, fig 5). Substance P caused a dose dependent increase in plasma t‐PA concentrations in both patients and controls (p < 0.01 for both, analysis of variance) (table 2). The substance P induced increase in plasma t‐PA concentrations did not differ during the sildenafil or placebo infusion (at 8 pmol/min, mean difference 0.02 ng/ml, 95% CI −1.15 to 1.18) (table 2) and plasma PAI‐1 concentrations did not change significantly throughout either study.

Table 2 Plasma tissue plasminogen activator (t‐PA) and plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 (PAI‐1) concentrations at baseline and during sildenafil and matched placebo infusion in patients with coronary heart disease.

| Sildenafil/placebo Substance P dose (pmol/min) | 0 | Bolus | Continuous infusion (10 mg/h) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 4 | 8 | |||

| Placebo | |||||

| Plasma t‐PA antigen (ng/ml) | |||||

| Infused arm | 9.0 (0.7) | 8.7 (0.6) | 9.3 (0.6) | 9.8 (0.7) | 10.5 (0.8)* |

| Non‐infused arm | 9.0 (0.6) | 9.1 (0.6) | 9.1 (0.6) | 8.9 (0.6) | 9.1 (0.6) |

| Plasma PAI‐1 antigen (ng/ml) | |||||

| Infused arm | 46.8 (6.9) | 43.1 (6.0) | 0 | 0 | 34.4 (5.4) |

| Non‐infused arm | 45.2 (7.1) | 45.5 (7.6) | 0 | 0 | 36.4 (6.3) |

| Sildenafil | |||||

| Plasma t‐PA antigen (ng/ml) | |||||

| Infused arm | 9.0 (0.6) | 8.7 (0.6) | 9.1 (0.6) | 9.4 (0.6) | 10.5 (0.7)* |

| Non‐infused arm | 9.1 (0.6) | 8.8 (0.6) | 9.0 (0.6) | 8.9 (0.6) | 9.0 (0.6) |

| Plasma PAI‐1 antigen (ng/ml) | |||||

| Infused arm | 44.0 (5.6) | 39.6 (4.6) | 0 | 0 | 36.0 (3.8) |

| Non‐infused arm | 47.9 (5.6) | 43.2 (4.9) | 0 | 0 | 38.6 (4.2) |

*p<0.001, analysis of variance for t‐PA response.

Control subject data on file (p = 0.003, analysis of variance for t‐PA response).

Figure 5 Infused (solid line) and non‐infused (dashed line) forearm blood flow (panel A) and estimated net release of tissue plasminogen activator (t‐PA) antigen (panel B) at baseline, during sildenafil (•) and matched placebo (○) infusion (shaded box), and subsequently with intrabrachial substance P (2, 4, 8 pmol/min) in patients with CHD. p < 0.01 analysis of variance for all, dose response for infused arm FBF and net t‐PA release.

DISCUSSION

We have shown that sildenafil, a selective PDE5 inhibitor, does not modify endothelium dependent vasodilatation or acute t‐PA release in men with stable CHD. However, sildenafil did augment the vasodilator effect of the exogenous nitric oxide donor sodium nitroprusside. Thus, while our study confirms the well described interaction of sildenafil with nitric oxide donors,10,16 we have found no evidence to support the contention that PDE5 inhibitors improve endothelium dependent vasomotor or fibrinolytic function in patients with CHD.

Compared with matched controls, patients with CHD exhibited impaired endothelium dependent responses to acetylcholine while having preserved vasodilator responses to the endothelium independent agonists sodium nitroprusside and verapamil. This prognostically significant impairment7,17 was evident in patients who were already receiving standard antianginal, antiplatelet, and lipid lowering treatments.

Sildenafil had no effect on peak flow mediated dilatation of the brachial artery in patients with CHD11 and reports on the vasomotor responses of the coronary vessels to sildenafil are conflicting. Herrmann et al18 found no change in coronary artery diameter, blood flow, or coronary vascular resistance, whereas Halcox et al11 reported enhanced coronary artery vasodilatation to acetylcholine. Unlike previous studies, we used a more robust double blind randomised placebo controlled crossover study design and have shown that PDE5 inhibition does not alter either endothelium dependent vasomotor or fibrinolytic function in patients with CHD or in age matched controls. Moreover, we used a bolus and continuous intravenous sildenafil infusion to minimise variations in plasma concentrations during the administration of each of the intra‐arterial vasodilators. This is an important study consideration given the short half life of sildenafil in humans.

We observed a decrease in mean arterial pressure in both patients and controls during administration of sildenafil that presumably reflected an augmentation of the vascular effects of basal vascular nitric oxide release and is mediated through an increase in cGMP. Our findings are consistent with the published haemodynamic data from both healthy volunteers19 and patients with CHD18,19,20 and confirm that we achieved a physiological effect with sildenafil infusion. The consistent vasodilatory response to the nitric oxide independent agonist verapamil makes it unlikely that administration of the PDE5 inhibitor impaired vascular smooth muscle function or obscured potentially beneficial effects on endothelial function. Moreover, both acetylcholine and substance P produced similar, consistent, and reproducible responses on both study days. This suggests that prolonging cGMP actions in patients with established atherosclerosis would not reverse endothelial dysfunction. As would be predicted from its mechanism of action, sildenafil augmented the responses to sodium nitroprusside, an exogenous nitric oxide donor, in both controls and patients with CHD.

There are several potential reasons for the differences observed in the effect of sildenafil on the acetylcholine and sodium nitroprusside responses. The modest decrease in acetylcholine induced vasodilatation21,22 seen after nitric oxide synthase inhibition suggests that non‐nitric oxide dependent pathways such as endothelium derived hyperpolarising factor (EDHF) may predominate particularly in the presence of endothelial dysfunction.23,24 Furthermore, differences in the relative contribution of endothelium derived nitric oxide across vascular beds may explain some of the previously conflicting data on the vascular responses to sildenafil.11,25,26 As well as endothelial dysfunction, atherosclerosis is associated with high concentrations of free radicals such as superoxide anion that rapidly react with nitric oxide to generate peroxynitrite, a powerful oxidant species that induces significant cellular damage and directly inhibits soluble guanylate cyclase.27 Elegant studies in animals with specific knockouts of nitric oxide dependent pathways also suggest that tissue specific downregulation of nitric oxide/cGMP, including cGMP dependent protein kinase, may be an early feature of endothelial dysfunction in atherosclerotic conditions.28,29 PDE5 inhibition would not be anticipated to influence changes in oxidative stress or directly affect cGMP independent nitric oxide molecular targets that contribute to endothelial dysfunction and atherogenesis. Therefore, the contrasting effects of sildenafil on acetylcholine and sodium nitroprusside induced vasodilatation are likely to reflect a major dependence on non‐nitric oxide mediated pathways, increased oxidative stress, and decreased nitric oxide bioavailability associated with CHD.

Although the precise mechanism underlying acute t‐PA release remains uncertain, several reports have previously suggested involvement of nitric oxide and cyclic nucleotides regulated by phosphodiesterases. In animals, pentoxifylline and its analogues, non‐selective phosphodiesterase inhibitors, increased acute t‐PA release30 and potentiated the effects of thrombolytic treatment.31 We and others have reported acute endothelial t‐PA release during intra‐arterial substance P,4,14 bradykinin,32 and methacholine33 infusions, as well as an inverse relation between acute t‐PA release and atherosclerotic plaque burden within the coronary circulation.34 In the present study, we have again shown a rise in both plasma t‐PA antigen concentrations and net t‐PA release with local intra‐arterial substance P infusion. However, infusion of sildenafil did not change basal plasma t‐PA concentrations or substance P induced t‐PA release. Therefore, enhancement of cGMP apparently does not directly augment endothelial t‐PA release in humans.

Although we found no such change in acute t‐PA release with substance P, sildenafil may improve the response to other agonists such as bradykinin, which causes B2 receptor mediated prostacyclin and nitric oxide generation.35 However, the dominant mechanism of t‐PA release with bradykinin appears to be nitric oxide and prostacyclin independent with coupling of the B2 receptor to the calcium dependent Gq/phospholipase C‐beta pathway.36 Some of the conflicting results on the effect of nitric oxide synthase inhibitors on t‐PA release may suggest that there is physiological redundancy within the nitric oxide dependent pathways which contribute to the regulation of acute t‐PA release in humans.

Study limitations

In light of the haemodynamic changes seen in our study, intrabrachial infusion of sildenafil in subsystemic locally active doses would be one approach to assess the direct vascular actions of PDE5 inhibition. However, sildenafil is metabolised by the liver to an active metabolite that accounts for nearly half of its phosphodiesterase inhibitory activity. Local intra‐arterial infusion would not assess the action of this important metabolite. The effect of long term PDE5 inhibitor therapy remains unclear, and further studies with women and patients with diabetes mellitus would be of interest, as these groups may show differences within nitric oxide dependent pathways.37,38

Conclusion

Despite being highly effective in the management of erectile dysfunction, sildenafil does not modify endothelium dependent vasomotor or fibrinolytic function in patients with CHD. Phosphodiesterase inhibitors have already shown promise as novel treatments for conditions such as chronic heart failure25 and pulmonary hypertension,39 and these areas clearly warrant further research. However, on the basis of our results, we believe that PDE5 inhibitors are unlikely to reverse the generalised vascular dysfunction seen in patients with CHD.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Geraldine Cummings, the Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Facility and Pamela Dawson for their assistance with this study.

Abbreviations

cGMP - cyclic guanosine monophosphate

CHD - coronary heart disease

FBF - forearm blood flow

PAI‐1 - plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1

PDE5 - phosphodiesterase type 5

t‐PA - tissue plasminogen activator

Footnotes

Grant support: This work was supported by an educational award from the Sildenafil Research Grants Programme 2002, Pfizer Inc, New York, USA. Dr Robinson is the recipient of a British Heart Foundation Junior Research Fellowship (FS/2001/047).

Competing interests: SDR has received financial support for attending scientific meetings from Pfizer Ltd; NAB was a member of a drug advisory committee evaluating sildenafil and has received and supervised research grants from Pfizer Ltd; DEN holds unrestricted educational grant awards and has undertaken paid consultancy for Pfizer Ltd.

References

- 1.Celermajer D S, Sorensen K E, Georgakopoulos D.et al Cigarette smoking is associated with dose‐related and potentially reversible impairment of endothelium‐dependent dilation in healthy young adults. Circulation 1993882149–2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Creager M A, Cooke J P, Mendelsohn M E.et al Impaired vasodilation of forearm resistance vessels in hypercholesterolemic humans. J Clin Invest 199086228–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Panza J A, Quyyumi A A, Callahan T S.et al Effect of antihypertensive treatment on endothelium‐dependent vascular relaxation in patients with essential hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 1993211145–1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Newby D E, Wright R A, Labinjoh C.et al Endothelial dysfunction, impaired endogenous fibrinolysis, and cigarette smoking: a mechanism for arterial thrombosis and myocardial infarction. Circulation 1999991411–1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pretorius M, Rosenbaum D A, Lefebvre J.et al Smoking impairs bradykinin‐stimulated t‐PA release. Hypertension 200239767–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meade T W, Ruddock V, Stirling Y.et al Fibrinolytic activity, clotting factors, and long‐term incidence of ischaemic heart disease in the Northwick Park heart study. Lancet 19933421076–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suwaidi J A, Hamasaki S, Higano S T.et al Long‐term follow‐up of patients with mild coronary artery disease and endothelial dysfunction. Circulation 2000101948–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cayatte A J, Palacino J J, Horten K.et al Chronic inhibition of nitric oxide production accelerates neointima formation and impairs endothelial function in hypercholesterolemic rabbits. Arterioscler Thromb 199414753–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wallis R M, Corbin J D, Francis S H.et al Tissue distribution of phosphodiesterase families and the effects of sildenafil on tissue cyclic nucleotides, platelet function, and the contractile responses of trabeculae carneae and aortic rings in vitro. Am J Cardiol 199983(5A)3C–12C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kimura M, Higashi Y, Hara K.et al PDE5 inhibitor sildenafil citrate augments endothelium‐dependent vasodilation in smokers. Hypertension 2003411106–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halcox J P J, Nour K R A, Zalos G.et al The effect of sildenafil on human vascular function, platelet activation, and myocardial ischemia. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002401232–1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Newby D E, Wright R A, Dawson P.et al The L‐arginine/nitric oxide pathway contributes to the acute release of tissue plasminogen activator in vivo in man. Cardiovasc Res 199838485–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benjamin N, Calver A, Collier J.et al Measuring forearm blood flow and interpreting the responses to drugs and mediators. Hypertension 199525918–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Newby D E, Wright R A, Ludlam C A.et al An in vivo model for the assessment of acute fibrinolytic capacity of the endothelium. Thromb Haemost 1997781242–1248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Newby D E, Witherow F N, Wright R A.et al Hypercholesterolaemia and lipid lowering treatment do not affect the acute endogenous fibrinolytic capacity in vivo. Heart 20028748–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ishikura F, Beppu S, Hamada T.et al Effects of sildenafil citrate (Viagra) combined with nitrate on the heart. Circulation 20001022516–2521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heitzer T, Schlinzig T, Krohn K.et al Endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and risk of cardiovascular events in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation 20011042673–2678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herrmann H C, Chang G, Klugherz B D.et al Hemodynamic effects of sildenafil in men with severe coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med 20003421622–1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jackson G, Benjamin N, Jackson N.et al Effects of sildenafil citrate on human hemodynamics. Am J Cardiol 199983(5A)13C–20C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Webb D J, Muirhead G J, Wulff M.et al Sildenafil citrate potentiates the hypotensive effects of nitric oxide donor drugs in male patients with stable angina. J Am Coll Cardiol 20003625–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vallance P, Collier J, Moncada S. Effects of endothelium‐derived nitric oxide on peripheral arteriolar tone in man. Lancet . 1989;ii997–1000. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Kamper A M, Paul L C, Blauw G J. Prostaglandins are involved in acetylcholine‐ and 5‐hydroxytryptamine‐induced, nitric oxide‐mediated vasodilatation in human forearm. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 200240922–929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bauersachs J, Popp R, Hecker M.et al Nitric oxide attenuates the release of endothelium‐derived hyperpolarizing factor. Circulation 1996943341–3347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Katz S D, Krum H. Acetylcholine‐mediated vasodilation in the forearm circulation of patients with heart failure: indirect evidence for the role of endothelium‐derived hyperpolarizing factor. Am J Cardiol 2001871089–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Katz S D, Balidemaj K, Homma S.et al Acute type 5 phosphodiesterase inhibition with sildenafil enhances flow‐mediated vasodilation in patients with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 200036845–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dishy V, Harris P A, Pierce R.et al Sildenafil does not improve nitric oxide‐mediated endothelium‐dependent vascular responses in smokers. Br J Clin Pharmacol 200457209–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vallance P, Chan N. Endothelial function and nitric oxide: clinical relevance. Heart 200185342–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ruetten H, Zabel U, Linz W.et al Downregulation of soluble guanylyl cyclase in young and aging spontaneously hypertensive rats. Circ Res 199985534–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Munzel T, Feil R, Mulsch A.et al Physiology and pathophysiology of vascular signaling controlled by cyclic guanosine 3′,5′‐cyclic monophosphate‐dependent protein kinase. Circulation 20031082172–2183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tranquille N, Emeis J J. The effect of pentoxifylline (Trental) and two analogues, BL 194 and HWA 448, on the release of plasminogen activators and von Willebrand factor in rats. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 19911835–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ambrus J L, Ambrus C M, Stadler S.et al Potentiation of thrombolytic therapy by enzyme combinations and with aspirin or pentoxifylline. J Med 199425145–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brown N J, Gainer J V, Stein C M.et al Bradykinin stimulates tissue plasminogen activator release in human vasculature. Hypertension 1999331431–1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stein C M, Brown N, Vaughan D E.et al Regulation of local tissue‐type plasminogen activator release by endothelium‐dependent and endothelium‐independent agonists in human vasculature. J Am Coll Cardiol 199832117–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Newby D E, McLeod A L, Uren N G.et al Impaired coronary tissue plasminogen activator release is associated with coronary atherosclerosis and cigarette smoking: direct link between endothelial dysfunction and atherothrombosis. Circulation 20011031936–1941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cockcroft J R, Chowienczyk P J, Brett S E.et al Effect of NG‐monomethyl‐L‐arginine on kinin‐induced vasodilation in the human forearm. Br J Clin Pharmacol 199438307–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brown N J, Gainer J V, Murphey L J.et al Bradykinin stimulates tissue plasminogen activator release from human forearm vasculature through B2 receptor‐dependent, NO synthase‐independent, and cyclooxygenase‐independent pathway. Circulation 20001022190–2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Forte P, Kneale B J, Milne E.et al Evidence for a difference in nitric oxide biosynthesis between healthy women and men. Hypertension 199832730–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brodsky S V, Morrishow A M, Dharia N.et al Glucose scavenging of nitric oxide. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2001280F480–F486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Michelakis E D, Tymchak W, Noga M.et al Long‐term treatment with oral sildenafil is safe and improves functional capacity and hemodynamics in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation 20031082066–2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]