Abstract

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common sustained arrhythmia, that substantially increases morbidity and mortality. AF is gaining in clinical and economic importance, with stroke and thromboembolism being major complications. In this article, the evidence for AF treatment trial of antithrombotic therapy is reviewed. Stroke risk stratification of patients with AF is discussed, and practical recommendations for thromboprophylaxis are presented.

Keywords: atrial fibrillation, stroke, anticoagulation, warfarin, aspirin

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a condition of increasing clinical and economic importance, being the most commonly encountered tachyarrhythmia in clinical practice.1,2 Of note, AF accounts for 1% of all National Health Service expenditures in the UK.3 The prevalence of AF is strongly age dependent, affecting 5% of people older than 65 years and nearly 10% of those aged > 80 years.4,5 Given the clear trend towards an increasingly aging population, the improved survival of patients with cardiovascular disease and the predominance of AF among older patients, the health care burden of AF is set to increase dramatically.6 Indeed, hospitalisation rates for AF have increased by two‐ to threefold in recent years and the prevalence of AF is projected to double over the next two generations.3,4,5,6,7

AF AND STROKE

AF is an independent predictor of mortality, as well as contributing to substantial morbidity and mortality from stroke, thromboembolism, and heart failure, and adversely affects quality of life.4,5,7

AF increases the risk of stroke four‐ to fivefold across all age groups, accounting for 10–15% of all ischaemic strokes and nearly a quarter of strokes in people aged > 80 years.8,9 This equates to an increased incidence of stroke, approximating 5% a year for primary events and 12% a year for recurrent events.2 Indeed, the age adjusted prevalence of AF among patients with ischaemic stoke has already risen by greater than 40% over the past 30 years.10 Of greater concern is that patients with AF who have a stroke have a worse outcome, with a higher mortality and morbidity, as reflected by greater disability, longer hospital stays, and lower rates of discharge than for those who have a stroke in the absence of AF.11,12,13

Even patients with paroxysmal (self terminating) and persistent AF (lasting more than seven days or requiring cardioversion) have a risk of stroke that is similar to that for patients with permanent AF.1,14 Patients with asymptomatic AF often have less serious heart disease (with a lower incidence of coronary artery disease, and better left ventricular function) but still have more cerebrovascular disease; importantly, the absence of symptoms does not confer a more favourable prognosis when differences in base line clinical parameters are considered.15

Ischaemic strokes among patients with AF are commonly caused by cardioemboli, most commonly from within the left atrial appendage.2,16 In addition, AF fulfils the Virchow's triad for thrombogenesis, with abnormal blood flow (for example, stasis within the left atrium or poor left ventricular function), abnormalities of the vessel wall (for example, endothelial/endocardial damage or other structural heart disease), and abnormalities of blood constituents (with abnormalities of coagulation, fibrinolysis, platelets, etc), resulting in a prothrombotic or hypercoagulable state.17,18 In AF, intracardiac thrombus in situ contains primarily fibrin and amorphous debris, whereas embolised thrombi comprise primarily fibrin and platelets, providing a plausible pathophysiological basis for why anticoagulation greatly reduces thromboembolism in AF.19 Indeed, abnormalities of platelets seen in AF may reflect underlying vascular disease rather than being due to AF itself, where abnormalities of coagulation predominate.20 Of note, the abnormalities of haemostasis in AF appear to be unrelated to underlying structural heart disease or aetiology of AF but can be altered by antithrombotic treatment and cardioversion, and have been related to adverse outcomes, including stroke and vascular events.17,18,21,22

ANTITHROMBOTIC TREATMENT FOR AF

Warfarin versus control/placebo

Five randomised controlled clinical trials have compared warfarin with either control or placebo for the primary prevention of stroke among patients with non‐valvar AF (see web table 1 on the Heart website–www.heartjnl.com/supplemental).w1–12 The EAFT (European atrial fibrillation trial) was a secondary prevention study comparing warfarin, aspirin, and placebo in patients with non‐valvar AF who had experienced a transient ischaemic attack or stroke within the previous three months.w6

Table 1 Summary of the main stroke risk stratification schemes for patients with atrial fibrillation.

| Risk stratification scheme | Risk strata | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Intermediate | Low | ||

| AFI (1994)w22 | High to intermediate risk: aged ⩾65 years; history of hypertension, CAD, or diabetes mellitus | Aged <65 years; no high risk features | ||

| SPAF (1995)w23 | Women aged >75 years; SBP >160 mm Hg; LV dysfunction (on echocardiography or clinically) | History of hypertension; no high risk features | No history of hypertension; no high risk features | |

| Lip (1999)w24 | All patients with previous TIA or cerebrovascular accident; all patients aged ⩾75 with diabetes or hypertension; all patients with clinical evidence of valve disease, heart failure, thyroid disease, and impaired LV function on echocardiography | All patients ⩾65 with clinical risk factors: diabetes, hypertension, peripheral vascular disease, ischaemic heart disease; all patients ⩾65 not in high risk group | All patients aged <65 with no history of embolism, hypertension, diabetes, or other clinical risk factors | |

| ACC/AHA/ESC guidelines (2001)1 | Aged ⩾60 years with diabetes or CAD; aged ⩾75 years (especially women); any age with risk factors (clinical heart failure, LVEF ⩽35%; thyrotoxicosis, or hypertension); rheumatic heart disease, prosthetic heart valves; previous thromboembolism; persistent atrial thrombus on TOE | Aged <60 years with CAD but no risk factors; aged ⩾60 years and risk factors | Aged <60 years and no risk factors | |

| CHADS2* (2001)w25, (2004)w26 | 3–6 | 1–2 | 0 | |

| Framingham (2003)w27 | Complicated weighted point scoring system—points are given for the following risk factors: ↑ age (maximum score ⩽10); sex (female = 6, male = 0); ↑ blood pressure (⩽4); and diabetes (6). Total score (maximum 31 points) corresponds to a predicted 5 year stroke risk | |||

| ACCP (2004)2 | Prior stroke, TIA, or systemic embolic event; aged >75 years; moderately to severely impaired LV function with or without CHF; hypertension or diabetes | Aged 65–75 years with no other risk factors | Aged <65 years with no risk factors | |

*Score one for each of the following: recent congestive heart failure, hypertension, aged ⩾75 years, diabetes. Score two if there is a history of stroke or transient ischaemic attack. Total score available is six. Although the original CHADS paperw25 did distinguish between high and low risk, the intermediate risk category was not defined until a subsequent analysis.w26

ACC, American College of Cardiology; ACCP, American College of Chest Physicians; AFI, Atrial Fibrillation Investigators; AHA American Heart Association; CAD coronary artery disease; CHF congestive heart failure; ESC European Society of Cardiology; LV, left ventricular; LVEF left ventricular ejection fraction; SBP systolic blood pressure; SPAF, stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation; TIA transient ischaemic attack; TOE transoesophageal echocardiography.

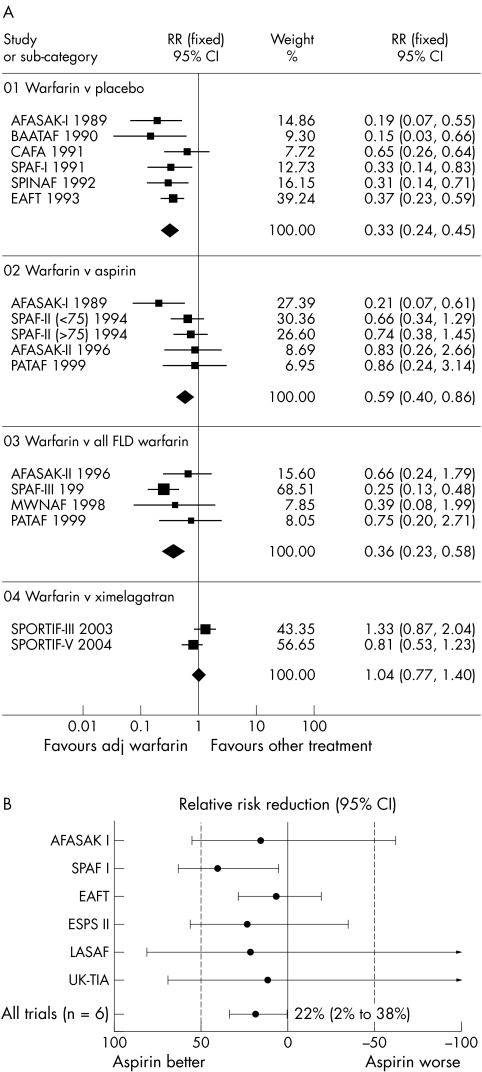

In a recent meta‐analysis of 13 trials (n = 14 423 participants) of thromboprophylaxis in AF, adjusted dose warfarin significantly reduced the risk of ischaemic stroke or systemic embolism compared with placebo (relative risk (RR) 0.33, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.24 to 0.45) (fig 1A).8,9 The risk reduction in total stroke did not differ statistically between the primary prevention studies and the single secondary prevention study (relative risk reduction (RRR) 59% v 68% in one analysis) but the absolute risk reduction for all stroke was far greater for secondary stroke prevention (8.4% a year; number needed to treat (NNT) for one year to prevent one stroke, 12) than for primary prevention (2.7% a year; NNT 37).w6 The rate of intracranial haemorrhage averaged 0.3% a year with oral anticoagulation versus 0.1% with placebo (not significant).w6 Furthermore, oral anticoagulation reduces all cause mortality (RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.53 to 0.89).8

Figure 1 (A) Meta‐analysis of ischaemic stroke or systemic embolism for adjusted dose (adj) warfarin compared with placebo, aspirin, fixed low dose (FLD) warfarin (with or without aspirin), and ximelagatran in patients with non‐valvar atrial fibrillation.8 AFASAK, Copenhagen atrial fibrillation, aspirin, and anticoagulation study; BAATAF, Boston area anticoagulation trial for atrial fibrillation; CAFA, Canadian atrial fibrillation anticoagulation study; CI, confidence interval; EAFT, European atrial fibrillation trial; MWNAF, minidose warfarin in non‐rheumatic atrial fibrillation; PATAF, primary prevention of arterial thromboembolism in non‐rheumatic atrial fibrillation; RR, relative risk; SPAF, stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation study; SPINAF, stroke prevention in nonrheumatic atrial fibrillation; SPORTIF, stroke prevention using the oral thrombin inhibitor in patients with non‐valvar atrial fibrillation. (B) Metaanalysis of trials comparing aspirin with placebo in reducing risk of thromboembolism in patients with atrial fibrillation.9 ESPS, European stroke prevention study; LASAF, low dose aspirin, stroke, and atrial fibrillation pilot study; UKTIA, United Kingdom transient ischaemic attack.

It is important to note that these trials had very different study designs, with varying intensity of anticoagulation used (international normalised ratio (INR) target range 1.4–4.5 for the five studies), follow up, and inclusion criteria. Warfarin was the oral vitamin K antagonists (VKA) of choice in all the studies, with the exception of EAFT, which used phenprocoumon or acenocoumarol.

Aspirin versus placebo

One meta‐analysis of the six main randomised trials of aspirin versus placebo has shown that aspirin significantly reduces the risk of stroke by 22% (95% CI 2% to 38%), with no significant increase in the risk of major haemorrhage (fig 1B).9 w1 w2 w6–9 Aspirin led to an absolute stroke risk reduction of 1.5% a year for primary prevention and 2.5% a year for secondary prevention (NNT of 67 and 40, respectively).9 In these studies, the dose of aspirin use was highly variable, ranging from 50–1200 mg/day. Furthermore, the inclusion criteria and length of follow up varied greatly (1.2–4 years) between the studies. While all six trials did show trends towards reduced stroke with aspirin, this result was driven largely by the SPAF (stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation) study, which was the only study to show a significant benefit, although aspirin had less effect in those aged > 75, nor did it prevent severe or recurrent strokes.w2

Indeed, analysis of stroke subtypes would support the beneficial effects of aspirin being largely driven by a reduction in non‐disabling (rather than disabling) stroke.9w2 Also, the RRR of stroke by aspirin compared with placebo of 22% is similar to the stroke risk reduction (22%) seen for the use of antiplatelets in high risk patients with vascular disease in the Antithrombotic Trialists' Collaboration.9w13 As AF commonly coexists with vascular disease, the effect of aspirin on stroke reduction in AF may simply reflect the effect on vascular disease, rather than AF.

Warfarin versus aspirin

One meta‐analysis of five randomised trials (AFASAK I (Copenhagen atrial fibrillation, aspirin, and anticoagulation study), SPAF II, EAFT, AFASAK II, and PATAF (primary prevention of arterial thromboembolism in non‐rheumatic atrial fibrillation)) comparing aspirin with warfarin for the primary prevention of stroke in AF showed that warfarin significantly reduced the risk of stroke compared with aspirin by 35% (95% CI 14% to 51%, p = 0.003, NNT 71).9 w1 w6 w10–12 w14 This was confirmed in the more recent meta‐analysis by Lip and Edwards,8 where adjusted dose warfarin was superior to aspirin in reducing the risk of ischaemic stroke or systemic embolism (RR 0.59, 95% CI 0.40 to 0.86) (fig 1A).

When only ischaemic strokes were considered, adjusted dose warfarin was associated with a 44% (95% CI 24% to 59%) RRR compared with aspirin (p < 0.001).w14 Furthermore, relative to aspirin, warfarin reduced cardiovascular events (RRR 24%, 95% CI 7% to 38%, p = 0.02). This was a heterogeneous group of clinical studies that all differed from each other in design. There was a non‐significant trend to increased haemorrhagic stroke risk with warfarin compared with aspirin (0.5% v 0.2%, hazard ratio 2.26, p = 0.06)

Combination VKA and antiplatelets

The initial trials testing the efficacy of either low intensity or normal intensity oral anticoagulation, in combination with antiplatelets, for the prevention of stroke for nonvalvar atrial fibrillation (AFASAK II, PATAF, SPAF III, and MIWAF (minidose warfarin in atrial fibrillation)) failed to achieve consistent superiority over traditional anticoagulation with VKA alone.w11 w12 w15 w16

The FFAACS (fluindione, fibrillation auriculaire, aspirin et contraste spontané (fluindione‐aspirin combination in high risk patients with AF)) study, which compared adjusted dose VKA plus aspirin against VKA alone, was stopped early for low recruitment and, thus, was underpowered (target was > 600) for the primary end point. Importantly, this study showed a high bleeding rate in the adjusted dose VKA plus aspirin combination treatment arm.w17

A recent multicentre randomised trial (NASPEAF (national study for primary prevention of embolism in non‐rheumatic atrial fibrillation)) of adjusted dose (INR 2.0–3.0) acenocumarol (a VKA), trifusal 600 mg/day (an antiplatelet agent), and acenocumarol‐trifusal combination in 1209 patients found the primary outcome was lower in the combined treatment than in the anticoagulant arm in both the intermediate risk (hazard ratio 0.33, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.91, p = 0.02) and the high risk group (hazard ratio 0.51, 95% CI 0.27 to 0.96, p = 0.03).w18 In this study, the combined antiplatelet plus moderate intensity anticoagulation did significantly decrease the vascular events compared with anticoagulation alone and proved to be safe in AF.w18 w19 Further studies with trifusal are needed to assess the role of this agent and of trifusal‐VKA combination treatment in AF.

Other strategies

Some studies have assessed very low intensity or fixed low dose anticoagulation in an attempt to reduce both the known haemorrhagic side effects of VKA and the burden of anticoagulation (SPAF III, AFASAK II, PATAF, and MIWAF) but results of these studies were inferior to treatment with conventional adjusted dose (INR 2.0–3.0) anticoagulation with VKA.w11 w12 w15 w16 In one meta‐analysis,8 adjusted dose warfarin was superior to fixed low dose warfarin in reducing the risk of ischaemic stroke or systemic embolism (RR 0.36, 95% CI 0.23 to 0.58) (fig 1A).

The SIFA (studio Italiano fibrillazione atriale) investigators compared indobufen, a reversible inhibitor of platelet cyclo‐oxygenase, with dose adjusted warfarin among 916 patients with non‐rheumatic AF and found a non‐significant trend towards benefit with warfarin; however, this was offset by a significantly increased intracerebral bleeding risk of warfarin compared with indobufen.w20

The ESPS‐2 (second European stroke prevention study) was a large trial comparing treatment with aspirin alone (50 mg daily), modified release dipyridamole alone (400 mg daily), aspirin–dipyridamole combination, or placebo among 6602 patients with prior stroke or transient ischaemic attack.w7 While the majority of included patients were in sinus rhythm, a post hoc retrospective subgroup analysis of the patients with AF reported a 36% RRR in stroke with combination treatment compared with placebo.w21

RISK STRATIFICATION IN AF

Given the established efficacy of anticoagulation among patients with increased risk of stroke and thromboembolism, it is important that treating physicians be given some guidance as to which patients should be considered for anticoagulation. Anticoagulation treatment needs to be tailored individually for patients on the basis of their age, co‐morbidities, contraindications, and most importantly individual stroke risk. Consequently, several risk stratification models of differing complexity have been introduced (table 1).2 w22–27 These schemes have been largely derived from the pooled analysis of the original antithrombotic treatment trials, although some have been derived from consensus. As table 1 shows, the identified clinical predictors tend to overlap across the various stratification schemes.

It is worth emphasising that risk factors are not mutually exclusive and are additive to each other in producing a composite risk. In the CHADS2 risk stratification scheme (recent congestive heart failure, hypertension, age, diabetes mellitus, history of stroke or transient ischaemic attack), for example, a numerical score is given to each of five risk factors, and the total score (⩽ 6) equates to a recognised future stroke risk (table 2).w25 In a study of pooled individual data from 2580 participants with non‐valvar AF who were prescribed aspirin in the AFASAK I and II, SPAF, and EAFT trials, the CHADS2 scheme appeared to have a greater predictive value for stroke than either the AF Investigators, SPAF criteria, Framingham score, or American College of Chest Physicians guidelines.w26 However, the incremental difference in risk between sequential CHADS2 scores makes it difficult to establish cut off values for antithrombotic treatment and, while a CHADS2 score of 0 would define a person as being at low risk (and suitable for aspirin) and ⩾ 3 as a high risk (and, thus, suitable for warfarin), therapeutic guidelines for intermediate risk CHADS2 values have not been clearly established. Moreover, patients with AF with previous stroke or thromboembolism are considered to be at high risk of a further stroke or thromboembolic event, but such patients with this risk factor alone would have a CHADS2 score of only 2, which would classify them as being at moderate risk.

Table 2 Relation between individual CHADS2 scores and risk of future strokew25.

| Risk factor | Individual score | Total CHADS2 score | % Adjusted stroke rate (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nil | 0 | 0 | 1.9 (1.2 to 3.0) |

| C (recent CHF) | 1 | 1 | 2.8 (2.0 to 3.8) |

| H (hypertension) | 1 | 2 | 4.0 (3.1 to 5.1) |

| A (age ⩾75 years) | 1 | 3 | 5.9 (4.6 to 7.3) |

| D (diabetes mellitus) | 1 | 4 | 8.5 (6.3 to 11.1) |

| S2 (history of stroke or TIA) | 2 | 5 | 12.5 (8.2 to 17.5) |

| 6 | 18.2 (10.5 to 27.4) |

CHF, congestive heart failure; CI, confidence interval; TIA, transient ischaemic attack.

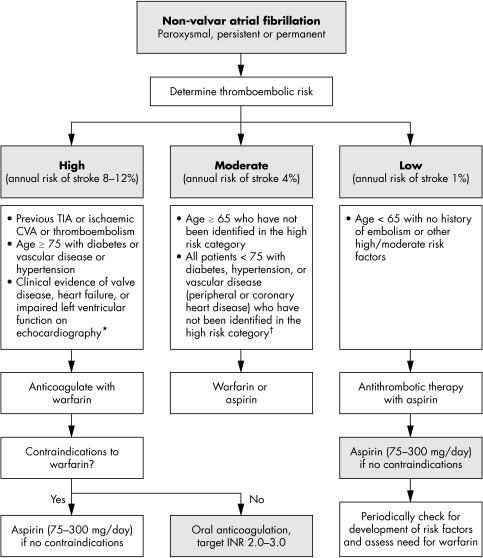

While these stroke risk stratification schema are important for identifying the high risk patients, more practical treatment guidelines are also clearly needed for antithrombotic treatment to direct treating physicians in their decision making process, offering a balance between evidence and practical applicability as fig 2 illustrates.23,24w26

Figure 2 Practical guidelines for antithrombotic therapy in nonvalvar atrial fibrillation.10 24 Assess risk, and reassess regularly. Note that risk factors are not mutually exclusive and are additive to each other in producing a composite risk. *An echocardiogram is not needed for routine risk assessment but refines clinical risk stratification in case of moderate or severe left ventricular dysfunction and valve disease. †Owing to lack of sufficient clear cut evidence, treatment may be decided on an individual basis, and the physician must balance the risks and benefits of warfarin versus aspirin; as stroke risk factors are cumulative, warfarin may, for example, be used in the presence of two or more risk factors. Referral and echocardiography may help in cases of uncertainty. Since the incidence of stroke and thromboembolic events in patients with thyrotoxicosis appears similar to other aetiologies of atrial fibrillation, antithrombotic treatments should be chosen based on the presence of validated stroke risk factors. CVA, cerebrovascular accident; INR, international normalised ratio; TIA, transient ischaemic attack.

ADMINISTERING ORAL ANTITHROMBOTICS IN AF?

When adjusted dose warfarin (or other VKA) is used, the INR should be maintained between 2.0–3.0 (target 2.5).2 At INRs > 3.0, the risk of haemorrhage increases exponentially and at INRs < 2.0 the risk of stroke increases.2 The increasing prevalence of AF means greater strains on anticoagulation monitoring clinics and the move to point of care testing or self monitoring strategies.w28–30

The dose of aspirin for AF thromboprophylaxis is more controversial, as aspirin doses below 75 mg daily have been suggested to be more effective than higher doses because such low doses are reported to “spare” prostacyclin (a platelet antiaggregant and vasodilator) and result in less gastrointestinal toxicity. In the large Antithrombotic Trialists' Collaboration meta‐analysis, the proportional reduction in vascular events was 19% with aspirin 500–1500 mg daily, 26% with 160–325 mg daily, and 32% with 75–150 mg daily; however, daily doses of aspirin < 75 mg had a somewhat smaller effect (proportional reduction 13%).w31 The RRR of aspirin versus control in the meta‐analysis of AF thromboprophylaxis trials was also 22%, which is similar to that seen in the Antithrombotic Trialists' Collaboration, for the reduction of vascular events (22%) by aspirin versus control in patients with vascular disease risk factors.9w31

As mentioned above, AF commonly coexists with vascular disease, and the benefits of aspirin in AF may simply relate to the effect on vascular disease, rather than thrombogenesis in AF. In trials involving AF populations alone, aspirin 75 mg/day was ineffective in the prevention of stroke in patients with permanent AF in one trial (AFASAK).w1 Aspirin 325 mg was beneficial in some studies, although in the SPAF trial, as mentioned above, aspirin appeared to be best for those aged < 75 years and did not prevent severe strokes or recurrent strokes.w2 The recent American College of Chest Physicians and American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/European Society of Cardiology guidelines recommend a dose of aspirin 300–325 mg, whereas other schema have recommended 75–300 mg daily.1,2 w25

Nonetheless, many patients with AF have concomitant vascular disease (coronary artery disease or peripheral artery disease) and anticoagulation is generally given based on the same criteria used for patients without such vascular disease (INR 2–3). Many clinicians administer a low dose of aspirin (< 100 mg/day) or clopidogrel (75 mg/day) concurrently with anticoagulation, supposedly for the vascular disease component, but such a strategy has not been evaluated sufficiently and may even be associated with an increased risk of bleeding. Indeed, in the AFFIRM (atrial fibrillation follow up investigation of rhythm management) trial, the most important predictor of bleeding in anticoagulated patients was concomitant aspirin use.w32 With the increasing use of coronary artery stents, the paucity of evidence—and the likely bleeding risk with triple treatment (warfarin and aspirin plus clopidogrel)—also means that many patients with AF have their warfarin temporarily stopped after coronary stent implantation and the aspirin–clopidogrel combination given for 2–4 weeks, followed by warfarin plus clopidogrel 75 mg. As recent guidelines recommend 12 months' aspirin–clopidogrel use with drug eluting coronary stents, the evidence is lacking on how best to manage patients with AF who have a drug eluting stent but need anticoagulation prophylaxis.w33

For patients with atrial flutter, it is generally recommended that patients follow the same risk stratification recommendations as for AF.2 For patients with AF ⩾ 48 hours (or of unknown or uncertain duration) for whom elective cardioversion is planned (electrical or pharmacological), anticoagulation with an oral VKA, such as warfarin (target INR 2.5, range 2.0–3.0), for at least three weeks before elective cardioversion and for a minimum of four weeks after successful cardioversion is recommended (table 3).2 An alternative strategy is anticoagulation and screening multiplane transoesophageal echocardiography (transoesophageal echocardiography guided cardioversion); if no thrombus is seen and cardioversion is successful, anticoagulation is continued for at least four weeks. However, adequate equipment and human resources are essential to implement a successful transoesophageal echocardiography guided cardioversion programme. This strategy may, however, be useful to allow early cardioversion of patients with AF > 48 hours or where a minimal period of anticoagulation is preferred. It is important to stress that in following cardioversion of all patients at high risk of AF recurrence or with stroke risk factors, consideration should be given towards long term anticoagulation, as thromboembolism may occur during (asymptomatic) recurrence of AF.

Table 3 Recommendations for anticoagulation for cardioversion of persistent atrial fibrillation (AF).

| • Administer warfarin for 3 weeks before elective cardioversion of AF of >48 hours' duration; and continue warfarin for 4 weeks after cardioversion |

| • An alternative strategy is anticoagulation and screening multiplane TOE; if no thrombus is seen and cardioversion is successful, anticoagulate for at least 4 weeks |

| • For patients with AF of known duration <48 hours, suggest cardioversion without anticoagulation; however, in patients without contraindications to anticoagulation, start intravenous heparin or low molecular weight heparin at presentation |

| • For patients with stroke risk factors or those at high risk of recurrence, consider long term treatment |

Based on the 7th ACCP Consensus Conference on Antithrombotic Therapy.2

Antithrombotic treatment of patients with AF presenting with acute stroke presents a problem, as there are few trials in this arena. Before starting any antithrombotic agent, a computed tomogram or magnetic resonance image should be obtained to confirm the absence of intracranial haemorrhage. In patients with AF with no evidence of haemorrhage and small infarct size (or no evidence of infarction) anticoagulation (aiming for INR 2–3) can be started, provided the patient is normotensive. In patients with AF with a large cerebral infarction, the initiation of anticoagulation should be delayed for 2–4 weeks due to the potential risk of haemorrhagic transformation. The presence of intracranial haemorrhage is an absolute contraindication to the immediate and future use of anticoagulation for stroke prevention in AF.

FROM CLINICAL TRIALS TO EVERYDAY PRACTICE

Despite the overwhelming evidence in support of adjusted dose warfarin in the prevention of stroke among patients with AF, there remains genuine concern as to how well this impressive trial data translates into the real world clinical setting. Patients in clinical practice are perceived to be sicker with less intensive anticoagulation monitoring than that undertaken in clinical trials. Nonetheless, several studies have confirmed the effectiveness of oral anticoagulation versus no anticoagulation for patients with AF in a variety of real world clinical settings, although these were all observational and non‐randomised studies.w34–38

We certainly know that the risk of stroke is greatest among very elderly patients (> 75 years) with AF, yet these are the patients who have been poorly represented in the antithrombotic treatment trials.w38 Most of these patients are in a high risk category but may equally have co‐morbidities and polypharmaceutical treatment that increases their risk of bleeding. Thus, careful assessment of risk to benefit ratio is needed and assessment of biological age rather than chronological age is sometimes helpful, as a fit active elderly person with a good quality of life would benefit from stroke prevention. The proposed protocol for the BAFTA (Birmingham atrial fibrillation treatment of the aged) study will assess the risks and benefits of aspirin 75 mg daily versus adjusted dose warfarin in elderly patients (age > 75 years) with AF in the primary care setting.w39

VKA such as warfarin also pose some practical issues. Warfarin has a slow onset and offset of action that extends over several days, with large inter‐ and intraindividual variability in dose response.w40 The therapeutic range for warfarin is also narrow, necessitating frequent venepuncture and dose adjustments to maintain a recommended INR range of 2.0–3.0.2 This narrow therapeutic range is important, as there is an increased propensity to ischaemic stroke with an INR < 2.0, whereas an INR > 3.0 has been shown to dramatically increase the risk of intracranial haemorrhage.w38 w41 In addition, warfarin is influenced by numerous food and drug–drug interactions, hepatic dysfunction, dietary vitamin K intake, and genetic variation in enzyme activity, as well as alcohol intake.w42–44

Despite well established evidence to support the clinical efficacy of warfarin, numerous observational studies have confirmed that under half of all patients eligible for warfarin for AF actually receive it.2 w45 Furthermore, even among patients prescribed warfarin (for AF), therapeutic anticoagulation (INR range 2.0–3.0) was achieved only about 50% of the time, with a greater tendency for patients to be subtherapeutically treated (INR < 2.0).w46 This is consistent with recent UK data where patients taking warfarin were outside the INR target range 32.1% of the time, with 15.4% INR values > 3.0 and 16.7% INR values < 2.0.w47 Of concern, a 10% increase in time out of range was associated with an increased risk of death (odds ratio 1.29, p < 0.001), ischaemic stroke (odds ratio 1.10, p = 0.006), other thromboembolic events (odds ratio 1.12, p < 0.001), and rates of hospitalisation.w47

Apart from the issues intrinsic to warfarin itself, anticoagulation for AF in clinical practice is still underused, with a prescription rate of only 15–44% among eligible AF patients.23 It is clear that several important barriers remain to the use of oral anticoagulation for AF. These can be broadly divided into barriers that are patient related (advanced age, poor understanding of the importance of anticoagulation, inconvenience of dosing, and perceived increased bleeding risks), physician related (poor application of clinical guidelines), and health care related (for example, the limited availability of anticoagulation monitoring systems).w48–50 There is no doubt that patients who are well informed about particular treatments have higher compliance rates, less anxiety, and improved outcomes over poorly informed patients.25 However, even despite careful counselling many patients still decline warfarin—the so called “informed dissent”.26 This further emphasises the responsibility to improve patient information and understanding regarding the importance, risks, and benefits of anticoagulation for AF.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS OF THROMBOPROPHYLAXIS FOR AF

The oral direct thrombin inhibitor ximelagatran was compared with warfarin in the SPORTIF (stroke prevention using the oral thrombin inhibitor in patients with non‐valvar atrial fibrillation) III and V trials, which have suggested the non‐inferiority of ximelagatran to dose adjusted warfarin (target INR 2.5, range 2.0–3.0) in moderate to high risk patients with non‐valvar AF.27,28 In the meta‐analysis by Lip and Edwards,8 ximelagatran was as effective as adjusted dose warfarin in the prevention of ischaemic strokes or systemic emboli (RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.40) with less risk of major bleeding (RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.56 to 0.96) (fig 1A). This new drug has few food, drug, or alcohol interactions and does not need anticoagulation monitoring; however, initial optimism has been tempered by the consistent association between ximelagatran and adverse alterations in liver enzyme activity, with alanine transaminase concentrations more than three times the upper limit of normal in about 6% of patients treated with ximelagatran versus 0.8% treated with warfarin for > 35 days.29 Other oral direct thrombin inhibitors are in clinical development and may prove to be viable alternatives to VKA.

Combination antiplatelet with clopidogrel and aspirin may be an alternative to VKA, by negating the need for anticoagulation monitoring. This hypothesis will be tested in the ongoing ACTIVE (atrial fibrillation clopidogrel trial with irbesartan for the prevention of vascular events) trial, which would be the first large scale trial (about 1400 patients) to assess the efficacy of combined antiplatelet and aspirin plus clopidogrel versus either warfarin (ACTIVE W) or aspirin (ACTIVE A) for the prophylaxis of vascular events with AF (permanent, paroxysmal, or persistent).30 However, enthusiasm for the aspirin–clopidogrel combination in AF has to be tempered by the lack of reduction of indices of thrombogenesis in AF and by the results of the MATCH (management of atherothrombosis with clopidogrel in high risk patients with recent transient ischaemic attack or ischaemic stroke) study, where combination treatment provided no significant clinical benefit, but substantially increased bleeding.20,31 Indeed, the ACTIVE W component of this trial was stopped in September 2005 on the recommendation of the trial data safety monitoring committee because warfarin appeared superior to the aspirin/clopidogrel combination arm in preventing vascular events.

Idraparinux is a long acting indirect factor Xa inhibitor, which is a synthetic analogue of the antithrombin binding pentasaccharide sequence found in heparin and low molecular weight heparin.32 The ongoing AMADEUS (atrial fibrillation trial of monitored, adjusted dose vitamin K antagonist, comparing efficacy and safety with unadjusted SanOrg 34006/idraparinux) study is comparing once weekly subcutaneous dosing with idraparinux versus warfarin in the thromboprophylaxis of stroke in AF, but bleeding risks with this once weekly administration of a drug with no specific antidote await evaluation.33 Oral factor Xa inhibitors are also in clinical development and may provide other viable alternatives to VKA.

CONCLUSION

AF can significantly increase morbidity and mortality, with stroke being the most serious complication. VKA such as warfarin are the mainstay of current anticoagulation practice for patients with AF at moderate to high risk of stroke. Aspirin use is reserved for patients at lower stroke risk or for those unable to tolerate VKA. Patients should be thoroughly educated about the rationale for anticoagulation before starting this treatment. The use of practice based guidelines and risk stratification schemes is to be encouraged so that evidence based practice can be implemented in the clinical arena.

Additional references appear on the Heart website—http://www.heartjnl.com/supplemental

Web table 1 and additional references appear on the Heart website—http://www.heartjnl.com/supplemental

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations

ACTIVE - atrial fibrillation clopidogrel trial with irbesartan for the prevention of vascular events

AF - atrial fibrillation

AFASAK - Copenhagen atrial fibrillation, aspirin, and anticoagulation study

AFFIRM - atrial fibrillation follow up investigation of rhythm management

AMADEUS - atrial fibrillation trial of monitored, adjusted dose vitamin K antagonist, comparing efficacy and safety with unadjusted SanOrg 34006/idraparinux

BAFTA - Birmingham atrial fibrillation treatment of the aged

CHADS2 - recent congestive heart failure, hypertension, age, diabetes mellitus, history of stroke or transient ischaemic attack

CI - confidence interval

EAFT - European atrial fibrillation trial

ESPS - European stroke prevention study

FFAACS - fluindione, fibrillation auriculaire, aspirin et contraste spontané

INR - international normalised ratio

MATCH - management of atherothrombosis with clopidogrel in high risk patients with recent transient ischaemic attack or ischaemic stroke

MIWAF - minidose warfarin in atrial fibrillation

NASPEAF - national study for primary prevention of embolism in non‐rheumatic atrial fibrillation

NNT - number needed to treat

PATAF - primary prevention of arterial thromboembolism in non‐rheumatic atrial fibrillation

RR - relative risk

RRR - relative risk reduction

SIFA - studio Italiano fibrillazione atriale

SPAF - stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation

SPORTIF - stroke prevention using the oral thrombin inhibitor in patients with non‐valvar atrial fibrillation

VKA - vitamin K antagonists

Footnotes

Competing interests: GL has received funding for research, educational symposia, consultancy and lecturing from different manufacturers of drugs used for the treatment of atrial fibrillation and thrombosis. He is Clinical Adviser to the Guideline Development Group writing the United Kingdom National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) Guidelines on atrial fibrillation management (www.nice.org.uk).

Web table 1 and additional references appear on the Heart website—http://www.heartjnl.com/supplemental

References

- 1.Fuster V, Ryden L E, Asinger R W.et al ACC/AHA/ESC guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: executive summary a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology committee for practice guidelines and policy conferences (committee to develop guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation) developed in collaboration with the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. Circulation 20011042118–2150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singer D E, Albers G W, Dalen J E.et al Antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation: the Seventh ACCP Conference on Antithrombotic and Thrombolytic Therapy. Chest 2004126(suppl)429S–56S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stewart S, Murphy N, Walker A.et al Cost of an emerging epidemic: an economic analysis of atrial fibrillation in the UK Heart 200490286–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freestone B, Lip G Y H. Epidemiology and costs of cardiac arrhythmias. In: Lip GYH, Godtfredsen J, eds. Cardiac arrhythmias: a clinical approach. Edinburgh: Mosby, 20033–24.

- 5.Go A S, Hylek E M, Phillips K A.et al Prevalence of diagnosed atrial fibrillation in adults: national implications for rhythm management and stroke prevention: the anticoagulation and risk factors in atrial fibrillation (ATRIA) study.JAMA 20012852370–2375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wattigney W A, Mensah G A, Croft J B. Increasing trends in hospitalization for atrial fibrillation in the United States, 1985 through 1999: implications for primary prevention. Circulation 2003108711–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benjamin E J, Wolf P A, D'Agostino R B.et al Impact of atrial fibrillation on the risk of death: the Framingham heart study. Circulation 199898946–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lip G Y H, Edwards S J. Stroke prevention with aspirin, warfarin and ximelagatran in patients with non‐valvular atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Thromb Res 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2005.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Hart R G, Benavente O, McBride R.et al Antithrombotic therapy to prevent stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta‐analysis. Ann Intern Med 1999131492–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsang T S, Petty G W, Barnes M E.et al The prevalence of atrial fibrillation in incident stroke cases and matched population controls in Rochester, Minnesota: changes over three decades. J Am Coll Cardiol 20034293–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marini C, De Santis F, Sacco S.et al Contribution of atrial fibrillation to incidence and outcome of ischemic stroke: results from a population‐based study. Stroke 2005361115–1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kimura K, Minematsu K, Yamaguchi T. Japan Multicenter Stroke Investigators' Collaboration (J‐MUSIC). Atrial fibrillation as a predictive factor for severe stroke and early death in 15,831 patients with acute ischaemic stroke. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 200576679–683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steger C, Pratter A, Martinek‐Bregel M.et al Stroke patients with atrial fibrillation have a worse prognosis than patients without: data from the Austrian stroke registry. Eur Heart J 2004251734–1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hart R G, Pearce L A, Rothbart R M.et al Stroke with intermittent atrial fibrillation: incidence and predictors during aspirin therapy. Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation Investigators.J Am Coll Cardiol 200035183–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flaker G C, Belew K, Beckman K.et al Asymptomatic atrial fibrillation: demographic features and prognostic information from the atrial fibrillation follow‐up investigation of rhythm management (AFFIRM) study. Am Heart J 2005149657–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manning W J, Silverman D I, Waksmonski C A.et al Prevalence of residual left atrial thrombi among patients with acute thromboembolism and newly recognized atrial fibrillation. Arch Intern Med 19951552193–2198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lip G Y H. Does atrial fibrillation confer a hypercoagulable state? Lancet 19953461313–1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choudhury A, Lip G Y H. Atrial fibrillation and the hypercoagulable state: from basic science to clinical practice. Pathophysiol Haemost Thromb 200333282–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wysokinski W E, Owen W G, Fass D N.et al Atrial fibrillation and thrombosis: immunohistochemical differences between in situ and embolized thrombi. J Thromb Haemost 200421637–1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kamath S, Blann A D, Chin B S.et al A prospective randomized trial of aspirin‐clopidogrel combination therapy and dose‐adjusted warfarin on indices of thrombogenesis and platelet activation in atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol 200240484–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vene N, Mavri A, Kosmelj K.et al High D‐dimer levels predict cardiovascular events in patients with chronic atrial fibrillation during oral anticoagulant therapy. Thromb Haemost 2003901163–1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Conway D S, Pearce L A, Chin B S.et al Prognostic value of plasma von Willebrand factor and soluble P‐selectin as indices of endothelial damage and platelet activation in 994 patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Circulation 20031073141–3145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iqbal M B, Taneja A K, Lip G Y H.et al Recent developments in atrial fibrillation BMJ2005330238–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chugh S S, Blackshear J L, Shen W K.et al Epidemiology and natural history of atrial fibrillation: clinical implications. J Am Coll Cardiol 200137371–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lane D, Lip G Y H. Anti‐thrombotic therapy for atrial fibrillation and patients' preferences for treatment.Age Ageing 2005341–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Howitt A, Armstrong D. Implementing evidence based medicine in general practice: audit and qualitative study of antithrombotic treatment for atrial fibrillation.BMJ 19993181324–1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olsson S B. Executive Steering Committee on behalf of the SPORTIF III Investigators. Stroke prevention with the oral direct thrombin inhibitor ximelagatran compared with warfarin in patients with non‐valvular atrial fibrillation (SPORTIF III): randomised controlled trial, Lancet 20033621691–1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.SPORTIF Executive Committee for the SPORTIF V Investigators Ximelagatran versus warfarin for stroke prevention in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. JAMA 2005293690–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boos C J, Hinton A, Lip G Y H. Ximelagatran: a clinical perspective. Eur J Intern Med 200516267–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hohnloser S H, Connolly S J. Combined antiplatelet therapy in atrial fibrillation: review of the literature and future avenues. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 200314S60–S63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Diener H C, Bogousslavsky J, Brass L M.et al MATCH investigators. Aspirin and clopidogrel compared with clopidogrel alone after recent ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack in high‐risk patients (MATCH): randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial, Lancet 2004364331–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tan K T, Makin A, Lip G Y H. Factor X inhibitors. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 200312799–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Idraparinux sodium: SANORG 34006, SR 34006. Drugs R D 20045164–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.