Abstract

Objectives

To study the clinical significance of infarct location during long term follow up in a trial comparing thrombolysis with primary angioplasty.

Design

Retrospective longitudinal cohort analysis of prospectively entered data.

Setting

Patients with acute ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

Patients

In the Zwolle trial 395 patients with acute STEMI were randomly assigned to intravenous streptokinase or PCI.

Main outcome measures

Survival according to infarct location and treatment after 8 (2) years of follow up.

Results

105 patients died: 63 patients in the streptokinase group and 42 patients in the primary PCI group (relative risk (RR) 1.6, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.0 to 2.6; p = 0.03). In patients with non‐anterior STEMI there was no difference in mortality between streptokinase and PCI treated patients (RR 1.1, 95% CI 0.6 to 2.1; p = 0.68) but the streptokinase group had significantly more major adverse cardiac events (MACE) than the PCI group (RR 2.1, 95% CI 1.2 to 3.6). The number needed to treat to prevent one MACE was four. In patients with anterior STEMI, mortality was higher in the streptokinase group than in the PCI group (RR 2.7, 95% CI 1.4 to 5.5; p = 0.004). The number needed to treat to prevent one death was five. Kaplan‐Meier analysis confirmed the benefits of primary angioplasty in the first year and showed additional benefit of PCI compared with streptokinase between 1–8 years after the acute event.

Conclusions

Patients with anterior STEMI have better long term survival when treated with PCI than with streptokinase. In patients alive one year after the acute event, PCI confers a significant additional survival benefit, probably due to better preserved residual left ventricular function.

Keywords: acute myocardial infarction, angioplasty, streptokinase, outcome

Reperfusion treatment in acute myocardial infarction aims at early and sustained reperfusion of the myocardium at risk.1 Reperfusion can be obtained by thrombolysis or by primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Several studies have reported better survival among patients with acute ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) treated with primary PCI than with thrombolysis.2,3 A previous pooled analysis of all randomised studies showed that clinical outcome was better with primary PCI than with thrombolysis.4 Therefore, nowadays more patients with acute STEMI are being treated with primary PCI. Recent studies have shown better survival among patients with acute STEMI treated with primary PCI, even when patients need to be transported for this treatment.5,6,7,8 A recent pooled analysis9 of all randomised trials, and a separate quantitative review of 23 randomised trials, comparing both reperfusion modalities10 confirmed better survival among patients with acute STEMI treated with primary PCI than with thrombolytic on site even when they had to be transported to a PCI centre. However, in daily clinical practice patients are still being treated with thrombolysis for logistical and non‐medical reasons, such as reimbursement.

Patients with anterior STEMI have worse clinical outcome than do patients with non‐anterior STEMI.11,12 This worse clinical outcome is related to a larger final infarct size and a subsequent lower residual left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), which is a powerful predictor of outcome.13,14 The clinical significance of infarct location during long term follow up in trials comparing thrombolysis with primary angioplasty has not been studied. We studied survival in the Zwolle trial patients according to infarct location, with a mean long term follow up of eight years.

METHODS

The patients have been described before.15 Briefly, 395 patients with acute STEMI were randomly selected for primary PCI or thrombolytic treatment. Baseline characteristics and clinical data, including infarct location and outcomes, were recorded on a dedicated database. Patients were enrolled if they had no contraindications for thrombolytic treatment; had symptoms of acute myocardial infarction lasting longer than 30 minutes, accompanied by an ECG with ST segment elevation of more than 1 mm (0.1 mV) in two or more contiguous leads; and presented within six hours or between 6–24 hours if there was evidence for continuing ischaemia. After providing informed consent, patients were randomly assigned to undergo primary PCI or to receive streptokinase. All patients received heparin and aspirin.

Patients assigned to streptokinase treatment received 1.5 MU intravenously over one hour. Patients assigned to primary PCI were immediately transported to the catheterisation laboratory. If the coronary anatomy was suitable for PCI, the procedure was performed with standard techniques. Global LVEF was measured by equilibrium radionuclide ventriculography between days 4–10 after treatment.16 Enzymatic infarct size was measured by cumulative enzyme release from five to seven serial measurements up to 72 hours after symptom onset was calculated.16 For all patients, additional revascularisation procedures were performed if indicated for symptoms or signs of myocardial ischaemia.17 Follow up information was obtained in September 2000. All outpatients' reports were reviewed and general practitioners were contacted by telephone. For patients who had sustained clinical events during follow up, hospital records were reviewed. Non‐fatal recurrent myocardial infarction was defined as the combination of chest pain, changes in the ST‐T segment, and a second increase in the serum creatine kinase concentration to more than twice the upper limit of normal. If the creatine kinase concentration had not decreased to normal, a second increase of more than 200 U/l over the previous value was regarded as indicating a recurrent infarction.16

Statistical analysis

The primary end points were death and the combined incidence of death and non‐fatal reinfarction (major adverse cardiac events (MACE)). All outcomes were analysed according to the intention to treat principle. Data were statistically analysed with SPSS 10.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA). Differences between group means were tested by two tailed Student's t test. A χ2 statistic was calculated to test differences between proportions, with calculation of relative risks (RRs) and exact 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The Fisher exact test was used when the expected value of cells was smaller than 5. Significance was defined as a value of p < 0.05. Cumulative survival (and mortality) curves were constructed according to the Kaplan‐Meier method,18 and differences between the curves were tested for significance by the log rank statistic.19 Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to estimate hazard ratios of variables that were significantly different in univariate analysis.20 Age (> 60 years) and left ventricular function (LVEF < 40%) were dichotomised for the multivariate analysis.

RESULTS

Of the 395 patients enrolled, 194 were randomly selected to undergo primary PCI and 201 to receive streptokinase. The groups were similar in age, sex, infarct location, previous myocardial infarction, and history of diabetes mellitus (table 1).

Table 1 Clinical variables and infarct size in the Zwolle trial patients.

| PCI (n = 194) | SK (n = 201) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age >60 | 94 (48%) | 109 (54%) | 0.25 |

| Men | 160 (82%) | 158 (79%) | 0.37 |

| Hypertension | 36 (19%) | 40 (20%) | 0.73 |

| Anterior MI | 77 (40%) | 74 (34%) | 0.60 |

| Previous MI | 38 (20%) | 31 (15%) | 0.29 |

| Diabetes | 16 (8%) | 16 (8%) | 1.00 |

| Infarct size | |||

| LVEF (%) | 49.8 (10.3) | 44.9 (11.3) | <0.001 |

| LDHQ72 | 939 (738) | 1289 (1144) | <0.001 |

LDHQ72, enzymatic infarct size, LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; SK, streptokinase.

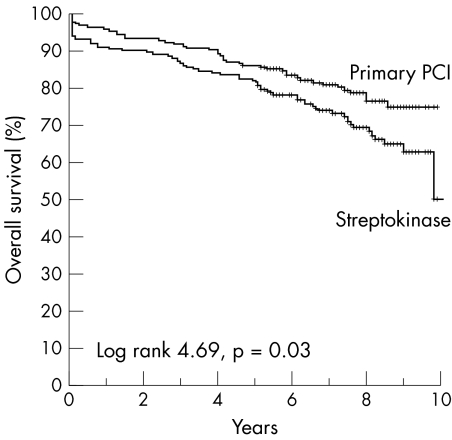

The residual LVEF was measured in 189 patients of the PCI group and in 188 patients of the streptokinase group. The mean LVEF was higher in the PCI group than in the streptokinase group (50% v 45%, p < 0.001). Enzymatic infarct size was measured in 367 patients (93%). Mean (SD) follow up was 8 (2) years. One patient was lost to follow up. At follow up a total of 105 patients had died. In the streptokinase group 63 (31%) patients died compared with 42 (22%) patients in the PCI group (RR 1.65, 95% CI 1.05 to 2.60). Fifty eight patients had a non‐fatal recurrent myocardial infarction: 13 (7%) patients in the PCI group and 45 (22%) in the streptokinase group (RR 0.25, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.48). All reinfarctions that occurred within the first 30 days affected the region of the index infarction. Of the 38 reinfarctions after day 30 (15 during the first year of follow up and 23 afterwards), 20 involved the original infarct related artery. The difference in the reinfarction rate was thus entirely due to events in the original infarct related artery. Figure 1 shows Kaplan‐Meier curves for overall survival of patient treated with streptokinase or with PCI.

Figure 1 Kaplan‐Meier curves for overall survival in the Zwolle trial in the percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and streptokinase groups during eight years of follow up.

Patients with non‐anterior STEMI in the Zwolle trial

Table 2 shows the baseline characteristics of the Zwolle trial patients according to the infarct location, either anterior or non‐anterior. In the group with non‐anterior STEMI baseline characteristics did not differ significantly between patients who underwent primary PCI and those who received streptokinase (table 2).

Table 2 Clinical variables and infarct size in the Zwolle trial patients according to infarct location.

| Anterior STEMI (n = 151) | Non‐anterior STEMI (n = 244) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCI (n = 77) | SK (n = 74) | p Value | PCI (n = 117) | SK (n = 127) | p Value | |

| Clinical variables | ||||||

| Age >60 | 31 (40%) | 43 (58%) | 0.03 | 63 (54%) | 66 (52%) | 0.78 |

| Men | 61 (79%) | 54 (73%) | 0.37 | 99 (85%) | 104 (82%) | 0.57 |

| Hypertension | 18 (24%) | 16 (22%) | 0.80 | 18 (15%) | 24 (19%) | 0.47 |

| Previous MI | 20 (26%) | 9 (12%) | 0.03 | 18 (15%) | 22 (17%) | 0.68 |

| Diabetes | 6 (8%) | 9 (12%) | 0.37 | 10 (8%) | 7 (5%) | 0.35 |

| Infarct size | ||||||

| LVEF (%) | 47 (12) | 38 (12) | <0.001 | 52 (9) | 48 (9) | 0.005 |

| LDHQ72 | 1117 (917) | 1592 (1261) | 0.01 | 822 (566) | 1099 (1027) | 0.01 |

STEMI, ST elevation myocardial infarction.

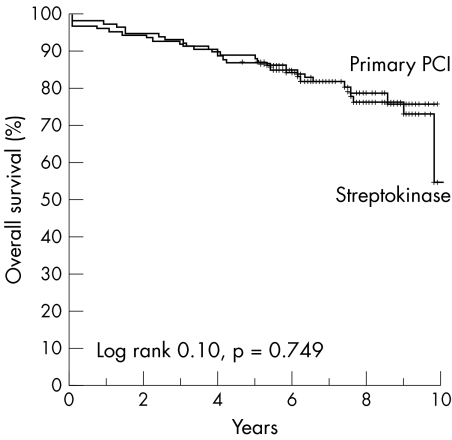

Enzymatic infarct size was larger in patients treated with streptokinase than in patients treated with primary PCI (1099 (1027) v 822 (566), p = 0.01). Residual LVEF was lower in patients treated with streptokinase than in patients treated with primary PCI (48 (9) v 52 (9), p = 0.005). At follow up, 23 (20%) patients with non‐anterior STEMI died in the group treated with PCI compared with 28 (22%) patients treated with streptokinase (RR 1.1, 95% CI 0.6 to 2.1; p = 0.68). Figure 2 shows Kaplan‐Meier curves for overall survival of patients with non‐anterior STEMI treated with streptokinase or PCI. The combined end point of MACE was significantly higher in the streptokinase group than in the PCI group: 50 (39%) patients in the streptokinase group and 28 (24%) patients in the PCI group (RR 2.1, 95% CI 1.2 to 3.6). The number needed to treat to prevent one MACE was four.

Figure 2 Kaplan‐Meier curves for overall survival after non‐anterior ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) in the PCI and streptokinase groups during eight years of follow up.

Patients with anterior STEMI in the Zwolle trial

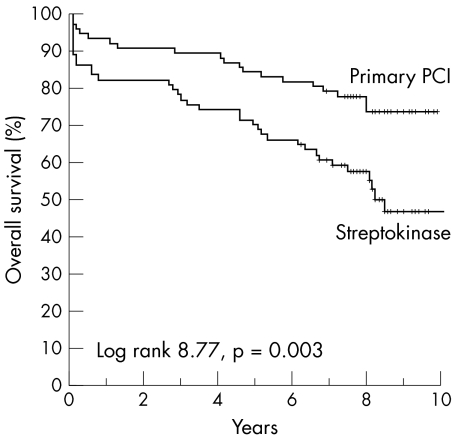

In the anterior STEMI patient group, the two treatment arms did not differ significantly in terms of sex and history of diabetes mellitus. In the anterior STEMI group, more patients with previous myocardial infarction were treated with PCI (26% v 12%, p = 0.03). The anterior STEMI patient group that received streptokinase was older than the patient group treated with PCI (age > 60 years: 58% v 40%, p = 0.03). Enzymatic infarct size was larger in patients treated with streptokinase than in patients treated with primary PCI (1592 (1261) v 1117 (917), p = 0.01). Residual LVEF was lower in patients treated with streptokinase than in patients treated with primary PCI (38 (12) v 47 (12), p < 0.001). At follow up, in patients with anterior STEMI, 35 (47%) patients in the streptokinase treated group died compared with 19 (25%) in the PCI treated group (RR 2.7, 95% CI 1.4 to 5.5; p = 0.004). The number needed to treat to prevent one death was five. Figure 3 shows Kaplan‐Meier curves for overall survival of patients with anterior STEMI according to treatment with streptokinase or PCI. In univariate analysis of patients with anterior STEMI, some baseline characteristics and residual left ventricular function differed between the PCI group and the streptokinase group. We included these variables (age > 60, previous MI, randomisation, and left ventricular function) in a multivariate model to study their independent value in assessing long term mortality. Multivariate analysis showed that age > 60 and random assignment to PCI treatment were equally strong predictors of long term mortality (table 3).

Figure 3 Kaplan‐Meier curves for overall survival after anterior STEMI in the PCI and streptokinase groups during eight years of follow up.

Table 3 Predictors of long term mortality in patients with anterior STEMI in the Zwolle trial.

| OR* | 95% CI | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age >60 v <60 | 2.2 | 1.2 to 3.8 | 0.01 |

| SK v PCI | 2.2 | 1.2 to 3.8 | 0.01 |

| Previous MI | 1.3 | 0.7 to 2.6 | 0.40 |

*Cox regression analysis.

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

When LVEF was included in the same model, the only two predictors of long term mortality were age > 60 and LVEF < 40% (table 4).

Table 4 Predictors of long term mortality in patients with anterior STEMI in the Zwolle trial with LVEF included in the model.

| OR* | 95% CI | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| LVEF <40% v >40% | 3.5 | 1.8–6.7 | <0.001 |

| Age >60 v <60 | 2.2 | 1.2–4.3 | 0.01 |

| Previous MI | 1.2 | 0.5–2.4 | 0.69 |

| SK v PCI | 1.2 | 0.6–2.4 | 0.54 |

*Cox regression analysis.

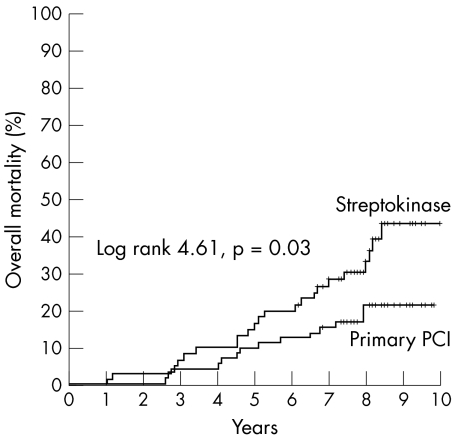

Significantly more patients in the streptokinase group than in the PCI group reached the combined end point of MACE: 44 (59%) patients in the streptokinase group and 25 (32%) in the PCI group (RR 3.0, 95% CI 1.7 to 5.9). The number needed to treat to prevent one MACE was four. We additionally analysed mortality in patients with anterior STEMI excluding deaths in the first year after the index myocardial infarction. From the total of 395 patients, 25 died in the first year. After the first year, 14 (19%) patients from the PCI treatment group died and 21 (36%) from the streptokinase treatment group (RR 2.3, 95% CI 1.1 to 5.1). Figure 4 shows significantly better survival for patients with anterior STEMI treated with PCI than with streptokinase, even when first year deaths are excluded from analysis.

Figure 4 Kaplan‐Meier curves for overall mortality after anterior STEMI without deaths in the first year of eight years of follow up in the PCI and streptokinase groups.

DISCUSSION

This study strongly supports our principal goal: that all patients with anterior STEMI should be treated with primary PCI. In the western world where randomised trials have shown PCI to be superior to thrombolysis, some patients are still being treated with thrombolytic regimens for several reasons. Although these reasons may be valid in some cases, it is essential that we treat patients who have proven long term benefit with primary PCI.

Non‐anterior STEMI: primary PCI versus streptokinase

In our study we did not find that patients treated with PCI had better long term survival than those treated with streptokinase. To show differences in outcome between treatment arms of patients with non‐anterior STEMI, large sample sizes, such as those used in thrombolysis studies, are necessary to show benefit of one regimen over another. Although we did not observe better long term survival, patients treated with PCI clearly had a significantly smaller infarct size as measured by residual LVEF (52 (9) v 48 (9), p = 0.005) and by enzymatic infarct size over 72 hours (822 (566) v 1099 (1027), p = 0.01). Residual LVEF is a known important end point of reperfusion and a strong predictor of long term outcome.13,14 Additionally, patients with non‐anterior STEMI who were treated with streptokinase had more recurrent myocardial infarctions needing additional admissions and treatment as shown by a significantly higher incidence of MACE in patients treated with streptokinase. Therefore, although long term survival did not differ significantly between treatment modalities, we conclude that for non‐anterior STEMI, primary PCI offers clinical benefits over treatment with streptokinase. In addition, patients with uncomplicated non‐anterior STEMI can be discharged 2–3 days after primary PCI.21

Anterior STEMI: primary PCI versus streptokinase

Our study clearly confirms that primary PCI is the treatment of choice for anterior STEMI. Patients treated with primary PCI had higher residual LVEF (47 (12) v 38 (12), p < 0.001) and smaller enzymatic infarct size (1117 (917) v 1592 (1261), p = 0.01). The absolute difference of residual LVEF was 9% in anterior STEMI when both treatment arms were compared, whereas this absolute difference was only 4% in the patients with non‐anterior STEMI in both treatment arms. These differences have been described before, but their importance becomes clear in the long term outcome.12 Furthermore, residual LVEF after primary PCI improves over time, especially in patients with anterior STEMI. Therefore, not only is residual LVEF better immediately after the index acute STEMI, but also long term recovery after STEMI, when treated with PCI, may contribute importantly to better survival.12,13

Patients with anterior STEMI had a much better survival when treated with primary PCI than when treated with streptokinase. Long term mortality was 25% in the PCI group and 47% in the streptokinase group. Therefore, there was a 22% absolute risk reduction for long term mortality; the number needed to treat to save one life is only five patients. Since some baseline characteristics differed between patients treated with primary PCI and with streptokinase, we studied the independent predictors of long term mortality with multivariate regression analysis. This analysis showed that age (> 60 years) and random assignment to PCI were the two predictors for long term survival among patients with anterior STEMI. However, when residual LVEF (< 40%) was included in this model, the two predictors for long term survival among patients with anterior STEMI were age (> 60 years) and residual LVEF (< 40%). This analysis shows that the long term improved survival of patients with anterior STEMI treated with PCI results from better preserved LVEF than when treated with streptokinase. Treatment with thrombolysis, as in our study with streptokinase, results in more recurrent myocardial infarction than after primary PCI. It is therefore conceivable that the better survival of patients treated with primary PCI would in part be due to the recurrent (fatal) reinfarctions that occur mainly within one year after the acute event. We therefore analysed long term mortality after excluding all deaths in the first year after the index acute STEMI. Figure 4 clearly shows the difference in mortality of patients with anterior STEMI when the two treatment modalities are compared.

Limitations

While multicentre thrombolysis trials have enrolled many thousands of patients with acute myocardial infarction undergoing reperfusion, we studied only 395 patients from a single centre. During the study period intracoronary stenting and glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor antagonists were not used. These two new treatments may well have a profound effect on clinical outcome.22,23,24

Conclusion

In all patients with acute STEMI, left ventricular function is better preserved by primary PCI than by treatment with streptokinase. In patients with acute anterior STEMI treated with primary PCI, the additional mortality benefit during long term follow is probably due to better preserved residual left ventricular function. The number needed to treat to prevent one death is five and the number needed to treat to prevent one MACE is four. In patients with non‐anterior STEMI treated with primary PCI, the principle benefit is the reduction in MACE. Independent predictors of long term mortality after acute anterior STEMI are age and residual left ventricular function.

Abbreviations

CI - confidence interval

LVEF - left ventricular ejection fraction

MACE - major adverse cardiac events

PCI - percutaneous coronary intervention

RR - relative risk

STEMI - ST elevation myocardial infarction

Footnotes

No conflicts of interest

References

- 1.Mukherjee D, Moliterno D J. Achieving tissue‐level perfusion in the setting of acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 20008539C–46C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Every N R, Parsons L S, Hlatky M.et al A comparison of thrombolytic therapy with primary coronary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 19963351253–1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zijlstra F, de Boer M J, Hoorntje J C A.et al A comparison of immediate coronary angioplasty with intravenous streptokinase in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 1993328680–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weaver W D, Simes R J, Betriu A.et al Comparison of primary coronary angioplasty and intravenous thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: a quantitative review. JAMA 19972782093–2098. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Madsen J K, Grande P, Saunamaki K.et al Danish multicenter randomized study of invasive versus conservative treatment in patients with inducible ischemia after thrombolysis in acute myocardial infarction (DANAMI). Circulation 199796748–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Andersen HR, Nielsen TT, Rasmussen K, et al; DANAMI‐2 Investigators. A comparison of coronary angioplasty with fibrinolytic therapy in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2003349733–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Widimsky P, Groch L, Zelizko M.et al Multicentre randomized trial comparing transport to primary angioplasty vs immediate thrombolysis vs combined strategy for patients with acute myocardial infarction presenting to a community hospital without a catheterization laboratory. The PRAGUE study. Eur Heart J 200021823–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Widimsky P, Budesinsky T, Vorac D, for the PRAGUE Study Group Investigators et al Long distance transport for primary angioplasty versus immediate thrombolysis in acute myocardial infarction: final results of the randomised national multicenter trial ‘Prague‐2'. Eur Heart J 20032494–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zijlstra F. Angioplasty vs thrombolysis for acute myocardial infarction: a quantitative overview of the effects of interhospital transportation. Eur Heart J 20032421–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keeley E C, Boura J A, Grines C L. Primary angioplasty versus intravenous thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: a quantitative review of 23 randomized trials. Lancet 200336113–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brener S J, Ellis S G, Sapp S K.et al Predictors of death and reinfarction at 30 days after primary angioplasty: the GUSTO IIb and RAPPORT trials. Am Heart J 2000139476–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ottervanger J P, van't Hof A W J, Reiffers S.et al Long‐term recovery of left ventricular function after primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J 200122785–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.St John Sutton M, Pfeffer M A, Plappert T.et al Quantitative two‐dimensional echocardiographic measurements are major predictors of adverse cardiovascular events after acute myocardial infarction: the protective effects of captopril. Circulation 19948968–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Norris R M, White H D. Therapeutic trials in coronary thrombosis should measure left ventricular function as primary end‐point of treatment. Lancet . 1988;i104–106. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Zijlstra F, Hoorntje J C A, de Boer M J.et al Long‐term benefit of primary angioplasty as compared with thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 19993411413–1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Boer M J, Suryapranata H, Hoorntje J C A.et al Limitation of infarct size and preservation of left ventricular function after primary coronary angioplasty compared with intravenous streptokinase in acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 199490753–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.European Society of Cardiology The task force on the management of acute myocardial infarction of the European Society of Cardiology. Acute myocardial infarction: pre‐hospital and in‐hospital management, Eur Heart J 19961743–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaplan E L, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc 195853457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Savage I R. Contributions to the theory of rank order statistics: the two‐sample case. Ann Math Stat 195627590–615. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cox D R. Regression models and life‐tables. J R Stat Soc [B] 197234187–202. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grines C L, Marsalese D L, Brodie B.et al Safety and cost‐effectiveness of early discharge after primary angioplasty in low risk patients with acute myocardial infarction. PAMI‐II investigators. Primary angioplasty in myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 199831967–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neumann F J, Blasini R, Schmitt C.et al Effect of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor blockade on recovery of coronary flow and left ventricular function after the placement of coronary‐artery stents in acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 1998982695–2701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stone G W, Brodie B R, Griffin J J.et al Clinical and angiographic follow‐up after primary stenting in acute myocardial infarction: the primary angioplasty in myocardial infarction (PAMI) stent pilot trial. Circulation 1999991548–1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stone G W, Grines C L, Cox D A, for the Controlled Abciximab and Device Investigation to Lower Late Angioplasty Complications (CADILLAC) Investigators et al Comparison of angioplasty with stenting, with or without abciximab, in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2002346957–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]