Abstract

Copy-choice recombination efficiently reshuffles genetic markers in retroviruses. In vivo, the folding of the genomic RNA is controlled by the nucleocapsid protein (NC). We show that binding of NC onto the acceptor RNA molecule is sufficient to enhance recombination, providing evidence for a mechanism where the structure of the acceptor template determines the template switch. NC as well as another RNA chaperone (StpA) converts recombination into a widespread process no longer restricted to rare hot spots, an effect maximized when both the NC and the reverse transcriptase come from HIV-1. These data suggest that RNA chaperones confer a higher genetic flexibility to retroviruses.

Reverse transcription is a key process in the life cycle of retroviruses, endogenous retroviruses, and class I transposons (1). The knowledge acquired during the last few years on retroviral replication makes retroviruses convenient for investigating the basic features of this process. A salient characteristic of reverse transcription is the high frequency of strand transfer (2). In retroviruses, genetic information is carried by two copies of single-stranded RNA present in the viral capsid. Intramolecular strand transfer is responsible for the generation of insertions and deletions (3), whereas intermolecular template switches eventually yield homologous recombination via a copy-choice mechanism (4). The impact of homologous recombination relies on the transfer, in a single cycle of replication, of a whole set of mutations into a new combination of alleles. In HIV-1, for instance, mutations selected as a result of antiviral treatment can be carried accurately from one genetic background to another, thereby increasing the rate of generation of resistant viral strains (5, 6).

Little is known about the sequence specificity of retroviral copy choice. The mere identification of recombination junctions generated during serial transfers of infective strains does not allow the identification of a sequence context favoring the process, because each recombination event potentially yields a progeny with an altered fitness. Although the development of model systems in cell cultures has allowed the study of recombination without the sieve of natural selection (7–9), a search for the sequence requirements for strand transfer in vivo has thus far demonstrated only the enhancing effect exerted by genomic homopolymeric runs (9).

In vivo, reverse transcription takes place on a ribonucleic complex, of which a major component is the nucleocapsid protein (NCp7 in the case of HIV) (10, 11). Because this protein is essential for viral viability, data concerning in vivo recombination in its absence cannot be obtained. In vitro, copy choice is enhanced strongly by NCp7 (12–14), although the molecular basis of this stimulation is still unknown. The analysis of two specific cases of strand transfer on naked RNA has led to the proposal of few mechanistic models (14, 15). Nevertheless, transposition of these putative models to the more complex situation of templates coated with NCp7 is not straightforward. Toward the understanding of the enhancing effect of NCp7, two salient features must be considered. On one hand, NCp7 acts as an RNA chaperone (16). As such, it favors the transient intramolecular rearrangement of RNA secondary structures (17) and the intermolecular annealing of complementary nucleic acids (18). Another protein, in this case of bacterial origin, has been shown in parallel assays to be also able to promote intermolecular annealing and to resolve misfolded RNA structures (17, 19). The two proteins, both classified as chaperones, display, however, unequal efficiencies depending on the RNA sequence used in the folding assay (17). Studies were therefore performed in this study with both proteins. Furthermore, NCp7 can interact specifically with the homologous HIV-1 reverse transcriptase (RT; ref. 20), a feature that could modify the ability of RT to switch template (21, 22). From these premises, we have investigated the role of NCp7 in RNA copy-choice recombination in a reconstituted in vitro system.

Materials and Methods

Plasmid Constructions and RNA Synthesis.

Plasmid p23P9 was obtained by insertion of four restriction sites by reverse PCR in pΔLA (described in ref. 23). The sites and positions relative to the beginning of the region of homology are given in the legend of Fig. 1. Similarly, pBL4 was obtained by insertion in pLK (described in ref. 23) of the restriction sites given in Fig. 1. These plasmids were used to synthesize the corresponding RNAs after restriction of pBL4 with SnaBI (donor RNA, BL4) or of p23P9 with PvuII (acceptor RNA, Δ23P9). For the experiments in which donor and the acceptor templates were switched, pBL4 was restricted with SnaBI, and p23P9 was restricted with BglI, yielding ΔBL4 and 23P9 RNAs. RNA synthesis by SP6 RNA polymerase (Promega) was performed for 1 h at 37°C, followed by the degradation of the DNA template by incubation with RNase-free DNase (Promega). The labeled RNAs used for gel retardation (see Fig. 3) were synthesized by incorporation of [α-32P]UTP. The RNA was purified by double acidic phenol chloroform extraction followed by double precipitation in ethanol with 3 M ammonium acetate. The integrity of the RNA was verified by agarose gel electrophoresis, and its amount was estimated by spectrophotometry.

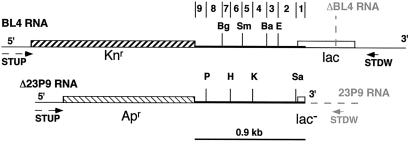

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the RNA templates used in this study. Drawing in black. Primer STDW was used to prime reverse transcription restricted to BL4, which thus constitutes the donor template. The region of homology between the two RNAs, constituted by the origin of replication of ColEI, is shown as a thicker line. The positions of the unique restriction sites present in the region of homology of either RNA are shown by letters: Sa (SacI, nucleotide 53 from the beginning of the region of homology in the sense of reverse transcription); E (EcoRI, nucleotide 212); Ba (BamHI, nucleotide 304); K (KpnI, nucleotide 390), Sm (SmaI, nucleotide 485); H (HindIII, nucleotide 573); Bg (BglII, nucleotide 643); and P (PstI, nucleotide 791). The intervals between the position of two sites define the nine regions into which the region of homology has been subdivided (see text). Dashed arrow, primer STUP, used for second strand synthesis; Apr and Knr, genes conferring resistance to ampicillin and kanamycin, respectively; lac or lac−, functional and nonfunctional copies of the lacZ′ gene, respectively; BL4, 3,250 nucleotides; Δ23P9, 2,200 nucleotides. Drawing in gray. For the experiments where donors and acceptor templates were switched, a truncated version of BL4 (named ΔBL4) was used, ending in the position shown by the dashed line. Conversely, an extended version of Δ23P9 (named 23P9) was used, carrying the same 3′ end as BL4 RNA (dashed line extending Δ23P9 RNA) that allows priming by STDW primer.

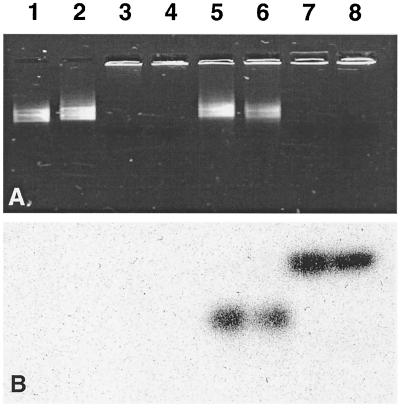

Figure 3.

Analysis by gel retardation of the selective coating of each RNA moiety by NCp7. All of the reactions were performed at 37°C in the buffer for reverse transcription before loading on a 1% agarose gel. (A) Lanes 1 and 2, 50 nM 23P9 or BL4, respectively, incubated for 30 min in the absence of proteins; lane 3, 50 nM 23P9 incubated with 5 μM NCp7 for 30 min; lane 4, 50 nM BL4 incubated with 7 μM NCp7 for 30 min; lane 5, 50 nM 23P9 incubated with 5 μM NCp7 for 5 min before addition of 50 nM labeled BL4 and further incubation for 30 min; lane 6, 50 nM BL4 incubated with 7 μM NCp7 for 5 min before addition of 50 nM labeled 23P9 and further incubation for 30 min; lane 7, 50 nM labeled 23P9 incubated with 5 μM NCp7 for 30 min; lane 8, 50 nM labeled BL4 incubated with 7 μM NCp7 for 30 min. (B) Autoradiogram of the gel shown in A. Quantification has been performed by the phosphorimaging technique and imagequant software (Molecular Dynamics).

Reverse Transcription and Estimation of the Frequency of Recombination.

Reverse transcription was performed in 50 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.8)/75 mM KCl/7 mM MgCl2/1 mM each dNTP/1 mM DTT/100 units of RNasin (Promega). Annealing (at a primer/template ratio of 1.5) was obtained by heating the reaction mixture (before the addition of the enzyme, the RNasin, DTT, and dNTPs) at 65°C for 5 min followed by slow cooling to 45°C. After incubation for 5 min on ice, DTT, RNasin, and nucleotides were included, and the reaction was started by the addition of RT. Each RT was used at final concentration of 400 nM (in active sites), and the RNAs were used at 50 nM each. When NCp7 (72 aa) or StpA was present (6 μM and 4 μM, respectively; concentrations that are sufficient to coat the RNA templates according to Negroni et al., ref. 13), the primer/RNA complex was incubated for 5 min at 37°C before addition of dNTPs and RT. After reverse transcription, these samples were treated with proteinase K (at a final concentration of 8 mg/ml) in 0.4% (wt/vol) SDS and 50 mM EDTA (pH 8.0) for 1 h at 56°C. The reaction was stopped by phenol chloroform extraction followed by incubation for 30 min at 37°C with 1 μg of DNase-free RNase and 0.5 units of Escherichia coli RNase H (both from Roche Molecular Biochemicals). Subsequent steps in the procedure were carried out as described (23): after purification by chromatography of the single-stranded product, the second strand was synthesized by Taq DNA polymerase, and the resulting full-length product was purified on agarose gels. The purified material was circularized by DNA ligase and used for transformation of E. coli. The frequency of recombination, unless otherwise stated, was estimated by the ratio of Apr colonies among the lac+ colonies, either Apr or Knr.

Evaluation of the Strength of Pauses During Reverse Transcription.

A primer hybridizing to region 4 was labeled by T4 DNA kinase and [γ-32P]ATP. Hybridization of the primer was carried out as described for the recombination assay. The reaction was started by addition of dNTPs (1 mM each) and HIV-1 RT and was stopped at various time intervals by addition of EDTA to a final concentration of 15 mM and heating for 5 min at 90°C. The samples containing NCp7 were treated as described above. For all samples, ethanol precipitation was performed before electrophoresis on a 7% (wt/vol) polyacrylamide gel containing 8 M urea in a loading buffer containing 22.5% (vol/vol) formamide. The intensity of each band was estimated with the phosphorimaging technique and imagequant software (Molecular Dynamics). The strength of each stop was evaluated by the equation Ai/(Ai + A>i), where Ai is the area of the peak corresponding to the band considered and A>i is the total area of the peaks corresponding to products longer than the band considered. This quantification was repeated for several incubation times ranging from 5 to 90 min, and the highest value obtained for each band was retained for subsequent computations. The present computation accounts for both reversible and irreversible pauses during reverse transcription (13).

Recombination Under the Conditions of Asymmetric Coating of the RNAs.

The coating of BL4 RNA was performed as follows. The primer for reverse transcription was annealed to 1 pmol of BL4 RNA, and incubation with 190 pmol NCp7 was carried out for 5 min at 37°C in the reverse transcription buffer. Δ23P9 RNA was added immediately before dNTPs and RT. The final concentration for each RNA moiety was 50 nM. The coating of 23P9 RNA was performed as follows. Δ23P9 RNA (1 pmol) was incubated with 130 pmol of NCp7. In parallel, 1 pmol of BL4 RNA was annealed to STDW as a separate sample. The preannealed STDW/BL4 mix was added to the NCp7/Δ23P9 complex immediately before dNTPs and the RT, yielding a final concentration of 50 nM for each RNA. When the donor and the acceptor templates were switched, the procedure followed was the same: BL4 was replaced by 23P9 RNA, and Δ23P9 was replaced by ΔBL4. The amount of NCp7 added for the coating was changed accordingly to the size of the new templates.

For the experiments of asymmetric coating and when HIV-1 was used, the mere ratio Apr/Knr + Apr colonies (or Knr/Knr + Apr for the experiments in which the donor and the acceptor templates were switched) was not a fair estimate of the recombination frequency. In this case, the presence of NCp7 on a given template decreases the yield of the corresponding full-length products that are cloned in our recombination assay (13). If only the acceptor template is coated with NCp7, after strand transfer, the probability of achieving a full-length reverse transcript is decreased, a penalty that does not apply to a reverse transcription that fully takes place on the initial template, devoid of NCp7. Conversely, when it is the donor RNA that is incubated with NCp7, reverse transcription can be interrupted irreversibly all along this template (which gives rise to wild-type DNA colonies), whereas this penalty affects only the recombinant DNA copy before the strand-transfer event. These penalties are a function of the length of the coated RNA that is reverse transcribed, and their values can be estimated from our previous study (see figure 6 in ref. 13). Appropriate corrections were therefore applied to the number of wild-type and recombinant colonies obtained in each assay. Because the donor and the acceptor templates are of unequal lengths, the synthesis of a full-length DNA is more difficult for the longer template. Therefore, a minor correction factor was applied to the overall frequency of strand transfer when NCp7 was present on both templates. NCp7 does not affect the overall yield of reverse transcription in the case of Moloney murine leukemia virus (MoMLV) RT (13), and no correction was applied in this case.

Results

In our recombination assay, reverse transcription is started on a given RNA, which, therefore, constitutes the donor template (BL4, Fig. 1), and is performed in the presence of an equimolar amount of an RNA acceptor template (Δ23P9, Fig. 1). Strand transfer occurring during reverse transcription of the region of homology between these two RNAs leads to the formation of molecules carrying the recombinant genotype lac+/Apr, and processive copying of BL4 yields a lac+/Knr genotype. Conversion of these single-stranded DNAs into a circular, double-stranded form generates plasmids that can be isolated after selection on ampicillin- or kanamycin-containing agar medium as described (23). The overall frequency of recombination is determined by the ratio between the Apr lac+ colonies and the total amount of lac+ clones, either Apr or Knr. Because the region of homology between the two templates includes several unique restriction sites (Fig. 1), each recombinant plasmid will be characterized by a specific restriction pattern that defines the sequence interval where strand transfer occurred. The recombination rate per nucleotide for each interval of the region of homology can thus be computed.

Two RTs on the Same Naked RNA.

A restriction analysis of 126 clones yielded consistent results in three independent experiments run with HIV-1 RT and revealed a nonrandom occurrence of strand transfer in each interval (σ, the standard deviation of the distribution of the crossovers within the intervals, is significantly greater than the uncertainty on the average frequency, Δr; see Table 1, column 3). Although the average recombination rate on the whole region of homology was 1.1 × 10−4 per nucleotide, regions 8 and 9 were found to behave as hot spots in all cases, with an average recombination rate of 2.1 × 10−4 and 3.7 × 10−4 per nucleotide, respectively; 70% of strand transfers occurred within these two regions, which constitute only 28.3% of the region of homology. When the experiment was repeated with MoMLV RT, although the overall average recombination rate was smaller (0.6 × 10−4 instead of 1.1 × 10−4 with HIV-1 RT), similar results were obtained with a bias in favor of the same intervals. Again, a large and significant fluctuation among the various intervals was observed (compare σ and Δr in Table 1, column 6).

Table 1.

Recombination rates

|

|

The weight wi attributed to each interval was its relative size in nucleotides (given in column 2 of the Table).

RNA Chaperones and Strand Transfer.

We studied the effect of the NC protein on the sequence specificity of the copy-choice process by coating the two RNAs by NCp7 before reverse transcription (as described in Materials and Methods). We first used the homologous system (NCp7 and HIV-1 RT): the rate of recombination increased then from 1.1 × 10−4 to 3.2 × 10−4 per nucleotide. The determination of the position of strand transfer showed that the enhancement was accompanied by a significant modification of the pattern of the hot spots (column 4 in Table 1 and Fig. 2A). As shown in Table 1, frequent strand transfer was no longer restricted to intervals 8 and 9. The increase in the overall recombination was mainly observed in regions where strand transfer was infrequent during the assays on naked RNA, with the strongest effect exerted on region 5. Although significant fluctuations in the recombination rates were still present (compare σ and Δr in Table 1, column 4), the distribution of the positions of strand transfer within the nine intervals considered was more homogeneous than for the naked RNA, as illustrated by the decrease in the ratio between standard deviation and average frequency of recombination (σ/r̄, last line in Table 1). NCp7 also enhanced recombination when reverse transcription was performed by MoMLV RT, as previously reported (13). In this case again, a change in the pattern of the positions of recombination was observed (Table 1, column 7). A significant increase was found in some “cold” intervals on naked RNA in regions 1 to 3, but region 8 was not affected, features reminiscent of the pattern obtained when the RNA templates were coated with NCp7 but reverse transcribed with HIV-1 RT.

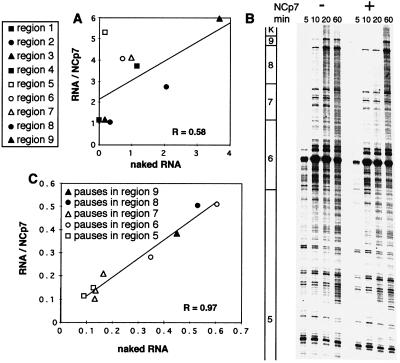

Figure 2.

|

1 |

The importance of the structure of the ribonucleic complex in the determination of the pattern of strand transfer is strengthened by the following experiment. NCp7 was substituted by the E. coli RNA binding protein StpA. An increase in recombination accompanied by a dramatic change in the pattern of strand transfer was again observed. However the new pattern was markedly different from the ones observed in the presence of NCp7. Strand transfer was now inhibited in region 9, increased in region 8, and not modified in regions 1 through 4 (Table 1, column 5).

In the presence of NCp7, the recombination frequency for the whole interval was above 30% for HIV-1 and 20% for MoMLV RTs. Such high frequencies resulted in the appearance of multiple crossovers, a phenomenon known to occur in vivo (8), with 3 triple recombinants found of 89 clones analyzed for HIV-1 RT and 2 found of 42 for MoMLV RT.

Involvement of Donor and Acceptor RNAs in Strand Transfer.

Because the changes in the local frequency of strand transfer triggered by NCp7 could be indirectly caused by a modification of the local parameters of DNA synthesis by RT, we performed labeled primer extension with a primer hybridizing to region 4, and reverse transcription was followed through the intervals from 5 to 9 for various incubation times. NCp7 increased the frequency of strand transfer in this portion of template from 8.6 to 22.1%. From the extension profiles shown in Fig. 2B and from their quantitative analysis through the correlation diagram given in Fig. 2C, it is clear that no equivalent increase is observed in the frequency of pausing and in their positions in the presence of NCp7 (R = 0.97; Fig. 2C). An analysis of the data as a function of the incubation times indicated that the duration of the pauses was not modified significantly either (not shown). Additionally, no significant correlation exists between the pattern of the main pausing sites (Fig. 2 B and C) and frequency of recombination in the intervals analyzed (Table 1, columns 3 and 4).

This lack of correlation led us to investigate further the respective role of the donor and of the acceptor templates in strand transfer. Selective coating by NCp7 either of the donor or of the acceptor RNAs was then attempted. The stability of the complex between NCp7 and these long RNAs was investigated by gel retardation (Fig. 3). To this end, the acceptor RNA was first incubated with the minimum amount of NCp7 required to complex all of the RNA (13). After 5 min of incubation at 37°C in the reverse transcription buffer, an equivalent amount of labeled donor RNA was added to the precomplexed acceptor moiety and incubated for an additional 30 min at 37°C (Fig. 3, lane 5). The same procedure was then applied precomplexing the donor RNA and adding labeled acceptor RNA (Fig. 3, lane 6). If reequilibration of NCp7 between the two templates occurred, we expect to see a partial retardation of the labeled RNA after 30 min of incubation. This retardation was not observed, and we found that the radioactive material retarded in lanes 5 and 6 of Fig. 3 corresponds to less than 5% (two independent experiments) of the radioactivity found in the bands of the free RNA. This incubation time is long enough to allow reverse transcription through the whole region of homology, which, as deduced from previous results, requires 30 min for HIV-1 RT and 10 min for MoMLV RT under our experimental conditions (13). It is thus possible to perform the recombination assay under conditions of selective coating either of the acceptor or of the donor templates. The experiment was run under the following conditions: (i) naked donor and acceptor RNAs; (ii) donor RNA coated with NCp7 and naked acceptor; (iii) acceptor coated with NCp7 and naked donor; and (iv) donor and acceptor both fully coated with NCp7.

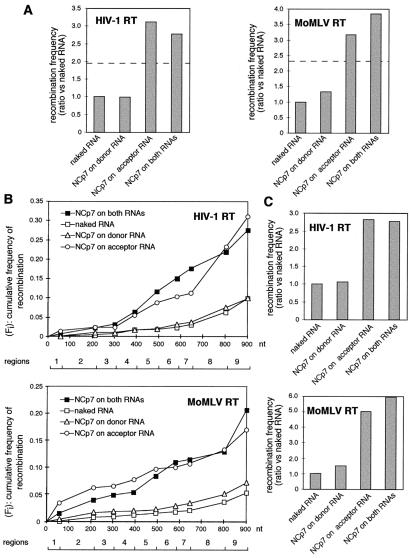

When reverse transcription was performed by HIV-1 RT, the selective complexation of one or the other type of template induced a clearly different effect on the overall frequency of recombination (Fig. 4A). The strongest stimulation was observed when NCp7 was bound to the acceptor RNA, a condition under which the recombination rate reached 3.5 × 10−4 per nucleotide, a value similar to the 3.2 × 10−4 observed when both RNAs were coated completely with NCp7 (Fig. 4A). In contrast, coating the donor template alone yielded a rate of 1.0 × 10−4 per nucleotide, a value almost identical to the one found for naked RNA (1.1 × 10−4). A similar result was obtained with MoMLV RT. In this case, the frequency of recombination underwent a 3.2-fold increase when the acceptor template was coated but only a 1.3-fold increase when the donor RNA was coated (Fig. 4A; recombination rates were 0.6 × 10−4 for naked RNA, 2.3 × 10−4 for both RNAs coated, and 1.9 × 10−4 and 0.8 × 10−4 for a coated acceptor or a coated donor, respectively). For both RTs, the contributions of the individual portions of the region of homology to the global frequency of recombination were strikingly similar when a donor RNA complexed with NCp7 or when naked templates were used (Fig. 4B). The profiles observed when both RNAs were complexed or when only the acceptor was complexed by NCp7 were similar, although not identical (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Frequencies of recombination under conditions of selective coating of donor and acceptor RNAs. (A) The frequency of recombination under each experimental condition is given as a ratio with respect to that occurring on naked RNA templates. Because the amount of NCp7 required to coat selectively either the acceptor or the donor RNAs was approximately half the amount required to coat both RNA moieties, we reasoned that the comparison among the different experimental conditions could be biased by a dose effect of NCp7. For this reason, we also ran a sample where equimolar amounts of both types of RNAs were mixed before adding half the amount of NCp7 required to coat them completely. The dotted horizontal line gives the ratio of enhancement obtained for these samples. (B) Plot of the cumulative frequency of recombination observed as reverse transcription progresses on the region of homology (from left to right in the figure). The gradual appearance of the recombination events is represented as a cumulative graph: if fi is the frequency of recombination in each interval, Fi = Σoifi. The values of Fi are plotted against the distance traveled through the homology region (in nucleotides). The recombination rate per nucleotide ri was assumed to be constant within each interval and is given by the slope of the corresponding segment of the curve. The value of Fi at nucleotide 901 (the end of the region of homology) gives the global frequency of recombination observed in the experiment. The number of individual colonies analyzed to generate the graphs in B for naked RNA, coated donor, coated acceptor, and both templates coated by NCp7 was, respectively, for HIV-1 RT, 126, 41, 39, and 89 and, for MoMLV RT, 92, 47, 49, and 83. (C) Results obtained after switching the role of donor and acceptor templates. The representation is the same as in A.

For the purpose of genetic screening, the region of homology is encompassed by different sequences on the donor and on the acceptor RNAs. To exclude any effect of this sequence context on our results, we have started reverse transcription by HIV-1 RT on 23P9 RNA while avoiding priming of BL4 RNA (see Fig. 1). The frequency of recombination is now given by the ratio between the Knr colonies and the total amount of clones, either Apr or Knr; 23P9 behaves now as donor and BL4 as acceptor template. Under these conditions, coating of the donor RNA alone again did not affect the recombination rate significantly (1.1 × 10−4 compared with 1.0 × 10−4 for naked RNA), and the presence of NCp7 on the acceptor template caused an increase in the frequency of recombination similar to the one observed when both moieties were coated with NCp7 (recombination rates 2.8 × 10−4 and 2.6 × 10−4, respectively). Similar results were obtained with MoMLV RT (Fig. 4C).

In conclusion, for both RTs used, selective coating of the acceptor template with NCp7 was sufficient to enhance the recombination rate to about the same extent as coating both RNAs, and the patterns of enhancement within the various intervals were analogous but not identical. For both RTs, the presence of NCp7 on the donor template did not markedly influence the frequency or the pattern of strand-transfer events observed with naked RNAs.

Discussion

The role of NCp7 in retroviral homologous recombination has been investigated. On naked RNAs, both RTs, from HIV-1 and from MoMLV, gave rise to a nonrandom distribution of template switches with a bias in favor of the same region of template, a feature that suggests a dominant role of the primary and secondary structures of the templates. NCp7 physiologically interacts with the genomic RNA and is known, in vitro, to affect the structures of the nucleic acids and to enhance strand transfer (4, 10, 12–14, 22). Several key features of the effect of NCp7 on strand transfer have been established herein: the extent of enhancement of strand transfer dramatically depends on the region of template considered; StpA, another RNA binding protein, also activates the process, yielding a pattern of strand transfer different from the one observed with NCp7; binding of NCp7 to the acceptor template is sufficient to account for most of the enhancement of recombination; and conversely, coating of the donor RNA does not significantly affect the process. A specific local folding of the RNA and particularly of the acceptor partner seems therefore to be required to optimize strand transfer. In any given region, the enhancement of recombination by NCp7 takes place without any significant change in the location in the intensity or the duration of the pauses detected within the corresponding interval. Therefore, although strand invasion might be favored by a transient arrest of DNA synthesis (15), the strength of this pause is not the parameter responsible for the dramatic improvement caused by NCp7.

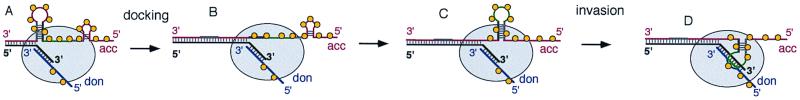

We reason that NCp7 most probably affects other steps of the process. Taking into consideration the different steps that have been proposed (12–15, 21, 22, 24) and the data presented herein, we envisage that strand transfer implies the formation of an intermediate complex containing both RNA templates and proceeds via two main steps: docking of the acceptor RNA on the nascent DNA and strand invasion. A plausible sequential order is depicted schematically in the model shown in Fig. 5. For each step, we can now examine how NCp7 can assist the process on the basis of the redistribution of the positions of strand transfer and the dominant role of the acceptor template reported in the present work. First, because both RNA-binding proteins used in this work promote the hybridization of complementary nucleic acids, they are likely to favor the docking step depicted in Fig. 5 A and B. Second, as a consequence of a more extensive hybridization with the nascent primer during DNA synthesis, the single-stranded region of the acceptor RNA could adopt other secondary structures as shown schematically in Fig. 5 B and C. Part of the enhancing effect of NCp7 and StpA could thus reside in their ability to increase, on the acceptor RNA, the number of secondary structures adopted during the search for the most stable folding, an intrinsic characteristic of RNA chaperones (16, 17). The various conformations explored by the acceptor RNA would display different efficiencies in the next step, the displacement of the DNA primer from the donor template (Fig. 5D). Because NCp7 and StpA vary in their efficiency to promote individual folding steps (17), this feature would account in part for the different local enhancement of strand transfer observed with these two proteins. Finally, the displacement reaction could be favored by interactions of the RT either with the RNA template, as proposed for strong-stop strand transfer (24), or with the RNA-binding protein. In the latter case, faint preferences of binding for certain RNA sequences by NCp7 or StpA could contribute to the differential enhancement observed with these two proteins. Among the possible combinations of chaperons and RTs used in this study, there is only one documented case of interaction: between NCp7 and HIV-1 RT (20). In this particular case, we observed the most homogeneous distribution of strand transfer along the template. We suggest that the interaction between NCp7 and a region of RT spanning the connection region and the RNase H site of the p66 subunit (20) could facilitate the strand displacement for any segment of template by efficiently bringing the acceptor RNA in closer proximity. This possibility is also supported by the higher affinity of the RT for the acceptor template measured in the presence of NCp7 (25). Interactions between NCp7 molecules present on the donor and those present on the acceptor could also participate to the strand displacement mechanism, accounting for the different patterns observed when NCp7 is present only on the acceptor or on both RNAs (Fig. 4B).

Figure 5.

How NCp7 could assist the acceptor template during recombination. Gray ellipse, RT; red and blue lines, acceptor and donor RNA templates, respectively; black lines, nascent DNA; acc, acceptor template; don, donor template. The light and dark boxes on the acceptor template represent stretches of inverted repeats. Strand transfer requires specific structural features on the acceptor template. (A–B) As polymerization proceeds, an efficient docking and an extensive hybridization imply the disruption of preexisting hairpins, as the one represented on the left side of A. (C) The presence of NCp7 on the acceptor template allows a fast search for the formation of new stable structures in the nonhybridized part of this RNA (sketched here as a new hairpin, drawn in green in its loop portion). (D) This particular structure is assumed to be competent for an invasion process, probably beginning from a portion in a single-stranded form. This step, which ultimately diverts the nascent DNA from the donor template, can be facilitated by NCp7–NCp7 and NCp7–RT interactions.

In conclusion, the presence of NCp7 yields recombination rates for HIV-1 RT (3 × 10−4 per nucleotide) in agreement with estimates made in vivo (8) and leads here to a rather homogeneous frequency of strand transfer. This last observation could have a major physiological implication. If efficient recombination on the RNA/NCp7 complex were restricted mostly to specific portions of the template, as for the naked model templates used in the present assays, transfer of genetic information would occur frequently but through the same segments of genome encompassed by rare hot spots. Several markers would thus remain associated in linkage groups. In contrast, a more homogeneous distribution of strand transfer, as observed with NCp7, leads to an efficient reshuffling of a larger number of individual markers, increasing the genetic flexibility of the viral population.

Acknowledgments

We are much indebted to Torsten Unge and Bernard Roques for their generous gifts of HIV-1 RT and NCp7, respectively. We also thank all of the members of the lab who contributed with helpful discussions. This work was supported by grants from the Agence Nationale pour la Recherche sur le SIDA to H.B. (95004 and 97004). M.N. is a recipient of a Sidaction fellowship.

Abbreviations

- RT

reverse transcriptase

- NC

nucleocapsid

- MoMLV

Moloney murine leukemia virus

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Article published online before print: Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 10.1073/pnas.120520497.

Article and publication date are at www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.120520497

References

- 1.Löwer R, Löwer J, Kurth R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:5177–5184. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.11.5177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Temin H M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:6900–6903. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.15.6900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pathak V K, Temin H M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:6024–6028. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.16.6024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coffin J M. J Gen Virol. 1979;42:1–26. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-42-1-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moutouh L, Corbeil J, Richman D D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:6106–6111. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.6106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Larder B A, Kellam P, Kemp S D. Nature (London) 1993;365:451–453. doi: 10.1038/365451a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu W S, Temin H M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:1556–1560. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.4.1556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu H, Jetzt A E, Ron Y, Preston B D, Dougherty J P. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:28384–28391. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.43.28384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wooley D P, Bircher L A, Smith R A. Virology. 1998;243:229–234. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Darlix J-L, Lapadat-Tapolsky M, de Rocquigny H, Roques B. J Mol Biol. 1995;254:523–537. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rein A, Henderson L E, Levin J G. Trends Biochem Sci. 1998;23:297–301. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01256-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rodriguez-Rodriguez L, Tsuchihashi Z, Fuentes G M, Bambara R A, Fay P J. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:15005–15011. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.25.15005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Negroni M, Buc H. J Mol Biol. 1999;286:15–31. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim J K, Palaniappan C, Wu W, Fay P J, Bambara R A. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:16769–16777. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.27.16769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeStefano J J, Bambara R A, Fay P J. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:161–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herschlag D. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:20871–20874. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.36.20871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clodi E, Semrad K, Schroeder R. EMBO J. 1999;18:3776–3782. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.13.3776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Remy E, de Rocquigny H, Petitjean P, Muriaux D, Theilleux V, Paoletti J, Roques B P. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:4819–4822. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.9.4819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang A, Derbyshire V, Salvo J L, Belfort M. RNA. 1995;1:783–793. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Druillennec S, Caneparo A, de Rocquigny H, Roques B P. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:11283–11288. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.16.11283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cameron C E, Ghosh M, Le Grice S F, Benkovic S J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:6700–6705. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.13.6700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peliska J A, Balasubramanian S, Giedroc D P, Benkovic S J. Biochemistry. 1994;33:13817–13823. doi: 10.1021/bi00250a036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Negroni M, Ricchetti M, Nouvel P, Buc H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:6971–6975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.15.6971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peliska J A, Benkovic S J. Science. 1992;258:1112–1118. doi: 10.1126/science.1279806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raja A, DeStefano J J. Biochemistry. 1999;38:5178–5184. doi: 10.1021/bi9828019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller J C, Miller J N. In: Statistics for Analytical Chemistry. 2nd Ed. Chalmers R A, Masson M, editors. Chichester, U.K.: Horwood; 1988. pp. 86–87. [Google Scholar]