Abstract

Pathological conditions linked to imbalances in oxygen supply and demand (for example, ischaemia, hypoxia and heart failure) are associated with disruptions in intracellular sodium ([Na+]i) and calcium ([Ca2+]i) concentration homeostasis of myocardial cells. A decreased efflux or increased influx of sodium may cause cellular sodium overload. Sodium overload is followed by an increased influx of calcium through sodium-calcium exchange. Failure to maintain the homeostasis of [Na+]i and [Ca2+]i leads to electrical instability (arrhythmias), mechanical dysfunction (reduced contractility and increased diastolic tension) and mitochondrial dysfunction. These events increase ATP hydrolysis and decrease ATP formation and, if left uncorrected, they cause cell injury and death. The relative contributions of various pathways (sodium channels, exchangers and transporters) to the rise in [Na+]i remain a matter of debate. Nevertheless, both the sodium-hydrogen exchanger and abnormal sodium channel conductance (that is, increased late sodium current (INa)) are likely to contribute to the rise in [Na+]i. The focus of this review is on the role of the late (sustained/persistent) INa in the ionic disturbances associated with ischaemia/hypoxia and heart failure, the consequences of these ionic disturbances, and the cardioprotective effects of the antianginal and anti-ischaemic drug ranolazine. Ranolazine selectively inhibits late INa, reduces [Na+]i-dependent calcium overload and attenuates the abnormalities of ventricular repolarisation and contractility that are associated with ischaemia/reperfusion and heart failure. Thus, inhibition of late INa can reduce [Na+]i-dependent calcium overload and its detrimental effects on myocardial function.

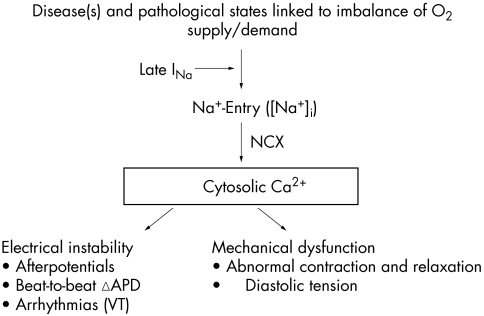

Cardiac function is dependent on homeostasis of the intracellular concentrations of sodium ([Na+]i) and calcium ([Ca2+]i). Pathological conditions such as ischaemia and heart failure are often associated with changes of intracellular concentrations of these ions and subsequent mechanical dysfunction (fig 1).1 An increase of [Na+]i may be the first step in disruption of cellular ionic homeostasis. This step may be followed by increases in sodium–calcium exchange, cellular uptake of calcium, and excessive calcium loading of the sarcoplasmic reticulum.2 Calcium overload of myocardial cells is associated with electrical instability, increased diastolic and reduced systolic force generation, and an increase in oxygen consumption.3 At the same time, the increase of diastolic force causes vascular compression and reduces blood flow and oxygen delivery to myocardium.4 Calcium overload may lead to cell injury and death if it is not corrected.

Figure 1 Increase in intracellular sodium concentration ([Na+]i) in pathological conditions linked to imbalances between oxygen supply and demand causes calcium entry through the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX). A pathologically enhanced late sodium current (INa) contributes to [Na+]i-dependent calcium overload, leading to electrical instability and mechanical dysfunction. APD, action potential duration; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

Cellular sodium and calcium homeostasis is maintained by ion channels, pumps and exchangers. This review summarises the cell processes involved in cardiac sodium and calcium homeostasis, the pathophysiology causing disruption of this homeostasis and the benefits of inhibiting the persistent or “late” sodium current (INa) to maintain ionic homeostasis and reduce cardiac dysfunction. Sodium and calcium ion channels, pumps and exchangers are prime targets for drugs intended to reduce [Na+]i, calcium overload and cardiac dysfunction. In the second half of this review we describe the cardioprotective effects of ranolazine, a selective inhibitor of late INa that is in clinical development for the treatment of angina pectoris.

SODIUM HOMEOSTASIS IN CARDIAC MYOCYTES

Homeostasis of [Na+]i is the result of a balance between the influx and efflux of sodium ions. Sodium influx and efflux occur by multiple pathways (table 1), many of which are subject to regulation.5 Depending on species and conditions, [Na+]i varies from 4–16 mmol/l in normal cardiomyocytes.5 The extracellular sodium concentration is about 140 mmol/l. The large transmembrane sodium concentration gradient, in conjunction with a negative resting membrane potential of about −90 mV, results in a substantial electrochemical gradient that favours sodium influx across the cell membrane. When sodium influx exceeds efflux, [Na+]i rises.

Table 1 Main pathways involved in the regulation of intracellular sodium concentration ([Na+]i) in cardiomyocytes.

| Pathway | Stoichiometry | Abbreviation |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium influx pathways | ||

| Sodium channel current (peak and late, through the voltage-gated sodium channel) | – | INa |

| Sodium-hydrogen exchanger | 1 Na+:1 H+ | NHE |

| Sodium-calcium exchanger (in forward mode) | 3 Na+:1 Ca2+ | NCX |

| Sodium-bicarbonate co-transporter | 1 Na+:1 HCO3− | NBC |

| Sodium-potassium-chloride co-transporter | 1 Na+:1 K+:2 Cl− | NKCC |

| Sodium-magnesium antiporter | 2 Na+:1 Mg2+ | NaMgX |

| Sodium efflux pathways | ||

| Sodium-potassium ATPase | 3 Na+:2 K+ | Sodium pump |

| Sodium-calcium exchanger (in reverse mode) | 3 Na+:1 Ca2+ | NCX |

Modified from Bers et al.5

There is general agreement that [Na+]i is raised in some pathological conditions, including cardiac ischaemia and reperfusion, hypertrophy and heart failure.6,7 The rise in [Na+]i during ischaemia and reperfusion appears to involve one or more of the following mechanisms: increased sodium-hydrogen exchange,7,8,9,10 decreased activity of the sodium-potassium ATPase (sodium pump)11 and increased sodium entry through sodium channels.7,8,9,10 The contributions of the sodium-bicarbonate co-transporter, the sodium-potassium-chloride co-transporter and the sodium-magnesium antiporter to the increase of [Na+]i during ischaemia and reperfusion appear to be minimal but have not been thoroughly investigated.5

Sodium-hydrogen exchanger

The sodium-hydrogen exchanger (NHE) is a proton (H+) extruder and an important regulator of intracellular pH and cell volume.12 NHE facilitates an electroneutral, passive exchange of intracellular hydrogen for extracellular sodium. The large transmembrane electrochemical potential gradient for sodium provides the energy that drives proton extrusion. The activity of NHE is very sensitive to small changes in the intracellular proton concentration, being low at the normal intracellular pH of 7.2 but greatly increased when intracellular pH decreases.13 Extracellular acidosis (that is, increased extracellular proton concentration) decreases the concentration gradient favouring hydrogen efflux and inhibits proton extrusion through NHE.

The relative contribution of NHE to total sodium influx at normal intracellular pH in stimulated (1 Hz) rabbit ventricular myocytes is < 5%.5 During acidosis (intracellular pH ⩽ 6.9), however, sodium influx through NHE may be as much as 39% of total sodium influx.5 Cellular depletion of ATP14 and extracellular acidosis are associated with a reduction of NHE. Regardless, inhibition of NHE during an ischaemic episode attenuates the ischaemia-induced rise in [Na+]i,10,15 suggesting that NHE is active during ischaemia. On reperfusion following ischaemia, extracellular pH rises towards normal and NHE increases, further loading the myocardial cell with sodium.9 The NHE-mediated increases of sodium influx and [Na+]i during reperfusion lead to increases in reverse mode sodium-calcium exchange and influx of calcium (see below). This series of events may explain the effect of the NHE inhibitors to protect against reperfusion injury.10

Sodium-potassium ATPase

The sarcolemmal sodium-potassium ATPase ion pump creates and maintains the differences in the extracellular and intracellular concentrations of sodium and potassium that are necessary for cell function.16 The free energy of hydrolysis of ATP is used by the ATPase to translocate three sodium ions from the cell cytoplasm to the extracellular fluid in exchange for two potassium ions that move in the opposite direction. This coupled transport is electrogenic and creates a small outward (repolarising) current. An increase of the [Na+]i increases the activity of the pump. Pump activity is decreased when the free energy of hydrolysis of ATP is less than that needed for ion transport. This may occur during prolonged, severe ischaemia17 when the intracellular concentration of ATP falls and concentrations of ADP and inorganic phosphate increase. The contribution of reduced sodium-potassium ATPase activity during mild ischaemia to increased [Na+]i may not be significant, however,9 and the activity of the sodium pump is not decreased but may be increased in heart failure.18

Sodium channel currents

Voltage-gated sodium channels are transiently activated on depolarisation of the cardiac cell membrane. The INa flowing through these channels is responsible for the upstroke (phase 0) of the action potential.19 It has been estimated that influx of sodium through sodium channels is about 19% of total sodium entry into rabbit ventricular myocytes when myocytes are stimulated at a rate of 1 Hz.5 Depolarisation of the cell membrane leads to a rapid increase of INa that lasts for a few milliseconds before sodium channels inactivate (that is, close). Recovery of each channel from inactivation requires repolarisation of the cell membrane and a change of the conformation of the channel from an inactivated to a resting closed state.

Although most sodium channels are inactivated within a few milliseconds and remain closed and non-conducting throughout the plateau phase of the cardiac action potential, a small percentage of channels either do not close, or close and then reopen.20,21,22 These channels may continue to open and close spontaneously during the action potential plateau for reasons that are not understood. The late channel openings allow a sustained current of sodium ions to enter myocardial cells throughout systole.23,24 This current has been referred to as late, sustained or persistent to distinguish it from the peak or transient INa. The amplitude of late INa is less than 1% of peak INa25 but it is sufficient to prolong action potential duration (APD).26 Thus, although the amplitude of late INa is small, because it persists for hundreds of milliseconds the influx of sodium by this mechanism may be substantial.2 The magnitude of late INa in canine mid-myocardial cells and Purkinje fibres is greater than that in either epicardial or endocardial myocytes (but see Noble and Noble2).27 The duration of action potentials in mid-myocardial cells and Purkinje fibres is also longer than in other cells of the heart.28 A role for late INa as a contributor to prolongation of APD is suggested by observations that lidocaine and tetrodotoxin shorten APDs of Purkinje fibres and ventricular mid-myocardial myocytes.26 Furthermore, transmural heterogeneity in the magnitude of late INa can cause transmural heterogeneity of APD that may have pathophysiological significance as a mechanism of ventricular tachyarrhythmias such as torsade de pointes.29

In recent years it has become clear that several experimental and pathological conditions can significantly increase the late component of the sodium channel current.30,31 These conditions (table 232,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40) include: (1) exposure of myocytes to peptides (for example, the sea anemone toxin, ATX-II),41 chemicals (for example, veratridine)42 and oxygen free radicals that slow the rate of inactivation of the sodium channel; (2) mutations in the sodium channel gene SCN5A that are associated with the long QT-3 syndrome43; and (3) disease states such as hypoxia, heart failure and post-myocardial infarction. It has been shown that hypoxia increases the amplitude of “persistent tetrodotoxin-sensitive sodium currents” (that is, late INa) in rat ventricular myocytes.32 The hypoxia-induced increase of late INa was observed experimentally at both the whole cell and the single channel current levels.32 The amplitude of late INa is reported to be increased 2–4-fold from 50–100 pA during normoxia to 180–205 pA during hypoxia.32 The mechanism of the hypoxia-induced increase of late INa has not been explained. Nevertheless, evidence exists that specific domains in an intracellular loop of the α subunit of the sodium channel play a part in channel inactivation and are targets for phosphorylation by protein kinase C.44,45

Table 2 Pathological and physiological conditions in which late sodium current is increased.

| Acquired pathological conditions |

| 1. Hypoxia32 |

| 2. Ischaemic metabolites (amphiphiles)33 34 |

| 3. Oxygen free radicals35 |

| 4. Heart failure (human and dog myocytes)30 36 37 |

| 5. Post-myocardial infarction “remodelled” myocytes38 |

| Physiological conditions |

| 6. Rat fetal ventricular myocytes39 |

| 7. Purkinje fibres and M cells from canine hearts27 |

| 8. Myocytes from subendocardium and epicardium of guinea pig hearts2 40 |

Sodium influx through late INa appears to be a major contributor to the rise of [Na+]i that is observed during ischaemia15 and hypoxia.32 Exposure of hearts to ischaemia is known to increase lysophosphatidylcholine, palmitoyl-l-carnitine and reactive oxygen species (for example, hydrogen peroxide), and these substances are themselves reported to increase late INa.31,35 Sodium channel blockers (for example, tetrodotoxin and lidocaine) have been shown to reduce the rise in [Na+]i in rat ventricular myocytes and isolated hearts during hypoxia and ischaemia, respectively.9,32,46,47 This action of sodium channel blockers is associated with an improvement of contractile function and with reduction of the hypoxia/ischaemia-induced increase in [Ca2+]i. Late INa is more sensitive to block by tetrodotoxin than is peak INa, and is also reduced by lidocaine, mexiletine, R-56865, flecainide, amiodarone, and ranolazine.31

Sodium-calcium exchanger

The major fraction (perhaps two thirds) of sodium influx into contracting myocytes is facilitated by the cell membrane sodium-calcium exchanger (NCX) and is thus in exchange for calcium efflux.5 The NCX is a facilitated diffusion whereby the electrochemical potential gradients of sodium and calcium are the source of energy to drive the transport. NCX generates an electrical potential because three sodium ions are exchanged for each calcium ion. In the “forward” mode, NCX facilitates the influx of sodium and efflux of calcium, and generates a net inward (that is, depolarising) transmembrane current. In the “reverse” mode, NCX facilitates the efflux of sodium and influx of calcium, and generates a net outward (that is, repolarising) current. The net transport of sodium by NCX is therefore sensitive to changes in the cellular concentrations of both sodium and calcium and the transmembrane electrical potential. During diastole, sodium influx and calcium efflux (the forward mode of NCX) are favoured. During the plateau of the action potential, calcium influx and sodium efflux (the reverse mode of NCX) are favoured. Conditions that increase the duration of the action potential plateau (as a portion of the cardiac cycle) are therefore associated with an increase of the reverse mode of NCX and increased net calcium influx.

Sodium-dependent calcium accumulation

A rise in the [Na+]i leads to an increased exchange of intracellular sodium for extracellular calcium through the reverse mode of NCX. There is general agreement that the cellular calcium overload that occurs during ischaemia and reperfusion is a result of a combination of decreased efflux of calcium ions through the forward mode of NCX and increased influx of calcium ions through the reverse mode of NCX.5,48,49 A relative increase of activity of NCX in the reverse mode (sodium efflux and calcium influx) is a predictable outcome of both a rise in [Na+]i and an increase in APD. As noted above, an increase of late INa causes both an increase of [Na+]i and a prolongation of APD, and thus increased activity of NCX in the reverse mode, and calcium influx. Direct evidence in support of the critical role of the reverse mode of NCX in intracellular calcium overload during reperfusion or reoxygenation after ischaemia is derived from the observations that inhibitors of NCX, and antisense inhibition of NCX, greatly decrease the rise in [Ca2+].50,51 Furthermore, a reduction of the rise in [Na+]i (caused by sodium channel blockers or inhibitors of sodium-hydrogen exchange) can greatly decrease intracellular calcium overload.7,8,9,46,47,50 This in turn reduces the cellular dysfunction and injury associated with ischaemia and reperfusion.

PROPOSED MECHANISM FOR THE CARDIOPROTECTIVE ACTIONS OF RANOLAZINE

Ranolazine has been reported to reduce the effects of ischaemia or simulated ischaemia on animal hearts in vivo52,53,54,55,56 or isolated, in vitro cardiac preparations,57,58,59,60 respectively. The cardioprotective effects of ranolazine are observed at concentrations that have minimal or no effect on heart rate, coronary blood flow and systemic arterial blood pressure.61 Likewise, in patients with chronic ischaemic heart disease (angina pectoris), ranolazine is an effective anti-ischaemic and antianginal drug at concentrations that cause minimal or no changes in heart rate and blood pressure.62,63 These observations led to the hypothesis that ranolazine exerts its antianginal and cardioprotective effects through a primary mode of action distinct from that of typical antianginal drugs such as calcium channel blockers, β adrenoceptor antagonists and nitrates.62,63

The mechanism of action of ranolazine has been difficult to elucidate and has only recently begun to be clarified. Results of early studies suggested that ranolazine altered myocardial energy metabolism to reduce fatty acid oxidation and increase glucose oxidation, although a reduction by ranolazine of fatty acid oxidation was observed only under selected experimental conditions.64,65,66,67 The inhibition by ranolazine of fatty acid oxidation appears to require relatively high concentrations of ranolazine (12% inhibition at 100 μmol/l),60 whereas cardiac function can be seen to improve in the presence ⩽ 20 μM ranolazine.57,68,69 Furthermore, ranolazine was found to improve heart function after exposure to hydrogen peroxide,69 ischaemia and reperfusion57,60 or palmitoyl-l-carnitine68 and during heart failure70 in the absence of fatty acids in the heart perfusion solution 57,69 and changes in fatty acid β oxidation,60 carbohydrate metabolism68 and fatty acid/glucose uptake,70 respectively. No specific step or enzyme in a metabolic pathway has been identified as a site of ranolazine action at concentrations that are similar to those at which ranolazine has beneficial effects in vitro and in vivo. In contrast, evidence is increasing that ranolazine is an inhibitor of late INa at concentrations ⩽ 10 μmol/l and that ranolazine reduces the electrical and mechanical dysfunction associated with conditions known to cause [Na+]i-dependent calcium overload. This evidence is reviewed below.

Inhibitions of late and peak INa by ranolazine

Ranolazine causes a concentration-, voltage- and frequency-dependent inhibition of late INa in canine71 and guinea pig41 ventricular myocytes. The potency of ranolazine to inhibit late INa varies from 5–21 μmol/l,31,71 depending on the experimental preparation, conditions and species, and possibly the sodium channel isoform (for example, brain or cardiac). Ranolazine has notably less effect on peak than on late INa.31 In isolated ventricular myocytes of dogs with chronic heart failure, ranolazine was found to inhibit peak INa and late INa with potencies (50% inhibitory concentrations) of 244 and 6.5 μmol/l, respectively.31 Hence, ranolazine was about 38-fold more potent in inhibiting late INa than peak INa.31 Amiodarone was about 13-fold more potent in inhibiting late than peak INa in the same preparation.72 The velocity of the upstroke (phase 0) of the action potential is proportional to the magnitude of peak INa. Thus, it is not surprising that the maximum upstroke velocity of phase 0 of the action potential (+Vmax) of canine Purkinje fibres is reduced by ranolazine only at high concentrations (⩾ 50 μmol/l).71 Additional evidence that ranolazine is a weak inhibitor of peak INa comes from a study of transepicardial activation times that used a high-resolution optical mapping system to measure action potentials.73 Ranolazine (⩽ 30 μmol/l) had no effect on transepicardial activation times, whereas lidocaine (75 μmol/l) increased total activation time from 15 to 24 ms.73 This finding suggests that the effect of ranolazine on peak INa at concentrations as high as 30 μmol/l is of little functional consequence for action potential +Vmax and impulse propagation, and that ranolazine is a selective blocker of late INa compared with peak INa at concentrations ⩽ 10 μmol/l.

The effects of ranolazine on various ion currents in ventricular potassium myocytes have been investigated.71,74 Table 371,75 summarises the potencies of ranolazine to affect these ion conductances in canine ventricular myocytes. Of note, ranolazine inhibits the potassium rapid delayed-rectifier current (IKr), with a potency of 11.5 μmol/l.71 This action of ranolazine is likely responsible for its effect to prolong the ventricular APD and the QT interval.62,76 In comparison, ranolazine is a very weak inhibitor of either the peak L-type inward calcium current (ICa,L) or the current generated by the NCX. The potencies of ranolazine to inhibit peak ICa,L and sodium-calcium exchange current (INa/Ca) were 296 and 91 μmol/l, respectively.71 This suggests that neither current is likely to play a part in the mechanism(s) underlying the therapeutic effects of ranolazine. There is no evidence that ranolazine inhibits the reverse mode of NCX. Reduction of the [Na+]i by ranolazine, however, could be expected to reduce both sodium efflux and calcium influx through the reverse mode of NCX.

Table 3 Potencies of ranolazine to inhibit transmembrane ion channel currents in canine ventricular myocytes.

| Inward currents | IC50 (μmol/l) | |

|---|---|---|

| INa | Peak INa | 240 |

| Late INa | ⩾5 | |

| ICa,L | Peak ICa,L | 296 |

| Late ICa,L | 50 | |

| INa/Ca | 91 | |

| Outward currents | ||

| IKr | 12 | |

| IKs | <20% at ⩾30 μmol/l | |

| IK1 | No effect | |

| Ito | No effect | |

IC50, concentrations of ranolazine that inhibit a given ion current by 50%.

All IC50 values are from Antzelevitch et al71 except for inhibition of peak INa (Undrovinas et al75).

ICa,L, L-type inward calcium current; IK1, inward rectifier current; IKr, rapid delayed-rectifier current; IKs, slow delayed-rectifier current; INa, late sodium current; INa/Ca, sodium-calcium exchange current; Ito, transient outward current.

The results of studies showing that ranolazine did not depress ventricular contractility or slow either heart rate in the conscious dog or atrioventricular nodal conduction in the rabbit heart77 are consistent with the results of studies of effects of ranolazine on cellular ion currents. Ranolazine at a concentration of 20 μmol/l had no effect on the NHE in MDCK cells.77 In summary, the transmembrane ion conductances most sensitive to ranolazine are the late INa and IKr. Therapeutic concentrations of ranolazine appear to have no effect on ICa,L, INa/Ca (NCX) or NHE, three important contributors to [Ca2+]i and [Na+]i homeostasis.

Reversal by ranolazine of ventricular repolarisation abnormalities in disease models and in the presence of drugs that increase late INa

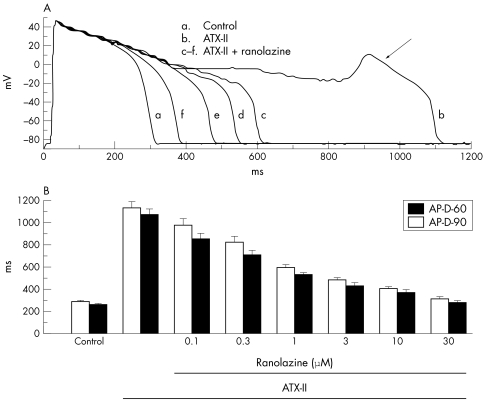

Cellular calcium overload can lead to spontaneous release of calcium from the sarcoplasmic reticulum, which in turn may cause repolarisation abnormalities.2,78,79 Raised [Ca2+]i activates [Ca2+]i-dependent ion currents (for example, INa/Ca; calcium-dependent chloride current; calcium-activated non-specific cation current) that can give rise to afterdepolarisations80 and an increase of beat-to-beat variability of APD. Both are harbingers of arrhythmias.81,82 An augmentation of late INa is expected to increase [Na+]i-dependent calcium entry through NCX, and thereby calcium loading of the sarcoplasmic reticulum, spontaneous calcium release and electrical instability. Consistent with this, some conditions known to increase late INa (table 2) and [Ca2+]i have been shown to cause arrhythmias. As summarised below, ranolazine reverses the ventricular repolarisation abnormalities associated with conditions and drugs known to increase late INa. Thus, the following findings are in keeping with the observation that ranolazine inhibits late INa of ventricular myocytes: (1) ranolazine decreases APD, measured at either 50% or 90% of repolarisation (APD50 or APD90, respectively), and abolishes early afterdepolarisations (EADs) of guinea pig ventricular myocytes treated with ATX-II41 (fig 2); (2) the potency of ranolazine to reverse these effects of ATX-II is 0.41 μmol/l41; and (3) tetrodotoxin, which reverses the increase in late INa caused by ATX-II, similarly reverses the ventricular repolarisation abnormalities (for example, APD prolongation and EADs) induced by ATX-II.41

Figure 2 Ranolazine attenuates the effects of the Anemonia sulcata toxin (ATX-II) on action potential duration (APD) and early afterdepolarisations (EADs) in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. (A) Recordings of action potentials from a ventricular myocyte in the absence of drug (control, (a)), in the presence of 10 nM ATX-II (b), and in the presence of ATX-II and increasing concentrations (1, 3, 10 and 30 μM) ranolazine (c–f). An EAD is indicated by the arrow in recording (b). (B) Concentration–response relationship for ranolazine to decrease APD in the presence of 10 nM ATX-II. Bars indicate the mean (SEM) of measurements from five to 10 cells. All values of APD in the presence of ranolazine are significantly different from ATX-II alone (p < 0.01). Reproduced with permission from Song et al.41

Ranolazine has been shown to have antiarrhythmic effects in a guinea pig in vitro model of the long QT-3 syndrome.83 Ranolazine (5, 10, and 30 μmol/l) attenuated the effect of 20 nM ATX-II to prolong the duration of the monophasic action potential in the guinea pig isolated perfused heart and suppressed the formation of EADs and occurrences of ventricular tachycardias.83 Ranolazine similarly antagonised the proarrhythmic actions of combinations of ATX-II and either the IKr blocker E-4031 or the slow delayed-rectifier current (IKs) blocker chromanol 293B.83 In the same long QT-3 model, ranolazine was found to suppress spontaneous and pause-triggered ventricular arrhythmic activity caused by a diverse group of IKr blockers (that is, moxifloxacin, cisapride, quinidine and ziprasidone).84 Thus, although ranolazine itself is an inhibitor of IKr (table 3), it appears not to potentiate (but may inhibit) the effects of other inhibitors of IKr.41,76,83,84 An effect of ranolazine (10 and 20 μmol/l) to reduce the incidence of ventricular fibrillation was also shown in a study of the rabbit isolated heart exposed to hypoxia and reperfusion in the presence of 2.5 mM external potassium concentration and the KATP channel opener pinacidil.59

In ventricular myocytes from dogs and humans with chronic heart failure (in which late INa is augmented), the APD is prolonged30,36,85 and EADs, aftercontractions and abnormal [Ca2+]i transients are common.85 Ranolazine inhibits late INa in ventricular myocytes from dogs with chronic heart failure with a potency of 6.4 μmol/l75 and, as expected, shortens APD and suppresses EADs in these myocytes at concentrations of 5 and 10 μmol/l.75 The sodium channel blockers tetrodotoxin, saxitoxin and lidocaine have likewise been shown to shorten the APD and suppress EADs in ventricular myocytes from failing hearts.36,37

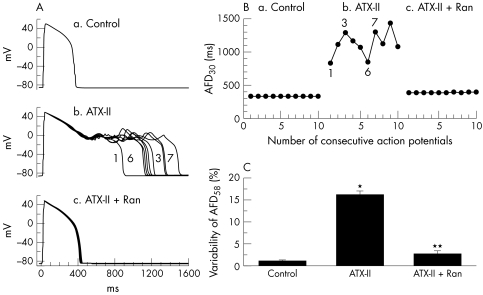

Dispersion and/or beat-to-beat variability of APD (also referred to as instability of APD) are often observed in myocytes from failing dog hearts, in ischaemic preparations and in myocytes exposed to either ATX-II or to drugs that prolong the QT interval. An increased dispersion of repolarisation is associated with electrical (T wave) and mechanical alternans and is proarrhythmic.86 The role of late INa in increasing beat-to-beat variability of APD and the suppression of this variability by tetrodotoxin, saxitoxin and lidocaine has been reported.36,37,87 Ranolazine (5 and 10 μmol/l) also reduces the variability of APD in single ventricular myocytes from dogs with heart failure75 and in myocytes exposed to ATX-II (fig 3).41 Thus, inhibition of late INa with ranolazine and other sodium channel blockers suppresses arrhythmogenic abnormalities of ventricular repolarisation (that is, EADs and increased dispersion of repolarisation) that are associated with abnormal intracellular calcium homeostasis and with the occurrence of torsade de pointes ventricular tachycardias.41,76,83,84

Figure 3 Effect of ranolazine (Ran) on variability of action potential duration (APD) in guinea pig ventricular myocytes exposed to Anemonia sulcata toxin (ATX-II). (A) Superimposed recordings of 10 consecutive action potentials from a myocyte in the absence of drug (a), in the presence of 10 nM ATX-II (b) and in the presence of 10 nM ATX-II and 10 μM ranolazine (c). (B) Graphic summary of the experiment shown in panel A. Each point represents the duration of a single action potential from a series of 10 action potentials recorded consecutively. (C) Summary of the results of all experiments similar to that shown in panels A and B. *p < 0.001 versus control; **p < 0.001 versus ATX-II. Reproduced with permission from Song et al.41

Reversal by ranolazine of mechanical dysfunction in disease models and in the presence of drugs that increase late INa

Intracellular calcium homeostasis has an important role in the regulation of left ventricular (LV) mechanical function.78 A significant increase in [Ca2+]i has been reported under a variety of experimental conditions involving exposures of cardiac tissues to ischaemia, hypoxia, oxygen free radicals, ischaemic metabolites, toxins and drugs. The excessive accumulation of intracellular calcium has been suggested to explain the ischaemic (and post-ischaemic) diastolic and systolic dysfunction and myocardial cell injury.1,3,49 As discussed above, this calcium overload is coupled to an increase in [Na+]i caused in part by an enhanced late INa. Hence, inhibition by ranolazine of this increased late INa should attenuate the LV mechanical dysfunction associated with several pathological conditions (see below).

Results of in vitro and in vivo studies of various cardiac preparations show that ranolazine can either prevent or reverse contractile and biochemical dysfunction in the ischaemic57 and failing heart,88 as well as in hearts exposed to the ischaemic metabolites palmitoyl-l-carnitine68 and hydrogen peroxide.69 Relevant to the hypothesis that ranolazine exerts its cardioprotective effect through inhibition of late INa, and consequently by reducing the sodium-dependent rise in [Ca2+]i is the substantial literature showing that sodium channel blockers are cardioprotective.1,6,7,8,42,46,47,89,90,91 The concept that the cytoprotective activity of sodium channel blockers to reduce ischaemia/reperfusion injury is principally mediated by inhibition of late INa has been proposed.1,9,47

Ranolazine attenuates contractile and biochemical dysfunction associated with ischaemia/reperfusion and anoxia/reoxygenation. Ischaemia/reperfusion and anoxia/reoxygenation increase LV diastolic pressure, a phenomenon attributed to calcium overload triggered by a rise in [Na+]i. The increases in LV diastolic pressure and tension can be mimicked by ischaemic metabolites such as palmitoyl-l-carnitine, lysophosphatidylcholine and reactive oxygen species.33,48,68,69 Common to all these conditions is an increase in late INa (table 2). The consequent rises in LV diastolic pressure and tension are associated with an increased rate of ATP hydrolysis, increased [Ca2+]i, increased release of creatine kinase, and histological evidence of cell damage.47,57,68,69,89

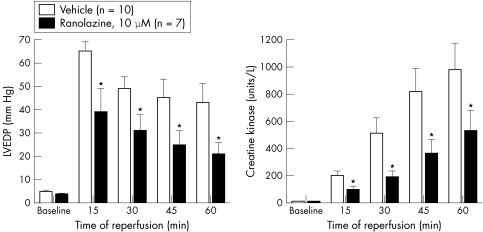

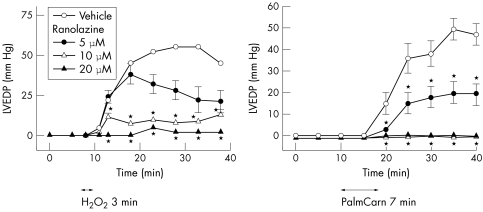

In rabbit and rat isolated perfused hearts, ranolazine (5–20 μmol/l) has been shown to significantly reduce ischaemia/reperfusion-, palmitoyl-l-carnitine- and hydrogen peroxide-induced increases in LV diastolic pressure and creatine kinase release, and decreases in tissue levels of ATP57,68,69 (figs 4 and 5). The reduction in ischaemia/reperfusion injury by ranolazine was associated with electron microscopic evidence of preservation of ultrastructural cell integrity.57

Figure 4 Effect of ranolazine on the left ventricular end diastolic pressure (LVEDP) and creatine kinase release of rabbit isolated Langendorff-perfused hearts. Hearts were subjected to 30 min of global ischaemia followed by 60 min of reperfusion. Hearts were treated with either ranolazine (10 μmol/l) or drug vehicle (dimethylsulfoxide plus saline) 10 min before ischaemia and throughout the period of ischaemia and reperfusion. Each value represents the mean (SEM).* Values significantly different (p < 0.05) from drug vehicle. Modified with permission from Gralinski et al.57

Figure 5 Effect of ranolazine to attenuate hydrogen peroxide- (H2O2; left graph) and palmitoyl-l-carnitine- (PalmCarn; right graph) induced increases of left ventricular end diastolic pressure (LVEDP) of rat isolated Langendorff-perfused hearts. Each value represents the mean (SEM) from six to eight hearts. *Values significantly different (p<0.05) from drug vehicle. Modified and reproduced with permission from Maruyama et al68 and Matsumura et al.69

The observation that ranolazine decreases post-ischaemic contracture (that is, increase of LV end diastolic pressure on reperfusion) has been recently confirmed.31 The post-ischaemic increase in LV end diastolic pressure, decrease in the rate of LV pressure development (LV+dP/dt), and decrease in the rate of LV pressure decline (LV−dP/dt), which are indices of contracture, contractility and relaxation, respectively, were significantly less in hearts treated with 5.4 μM ranolazine than in vehicle-treated hearts.31 Ranolazine, as well as lidocaine and mexiletine, increase the time to onset and reduce the rate of development of contracture of isolated rat left atria that are exposed to ATX-II.92

The most plausible explanation for the cardioprotective effect of ranolazine is its action to inhibit late INa, and consequently to reduce pathological increases of [Na+]i and [Ca2+]i. Two recent studies support this hypothesis.93,94 Ranolazine was found to attenuate significantly the increases in diastolic and systolic [Ca2+]i caused by the sea anemone toxin ATX-II. ATX-II increases late INa and thereby mimics the effects of ischaemia/reperfusion to increase [Na+]i and [Ca2+]i. The concentration-dependent attenuation by ranolazine (4.4 and 8.5 μmol/l) of the rise in [Ca2+]i caused by ATX-II was accompanied by a reduction of the ATX-II-induced (a) decrease in LV minute work (LV mechanical function), (b) decrease in LV systolic pressure and rise in LV end diastolic pressure, (c) decreases in both peak LV+dP/dt and LV−dP/dt, and (d) increase of myocardial lactate release.93,94 In addition, ATX-II decreased coronary flow and coronary vascular conductance (caused by the increase in LV end diastolic pressure, and hence diastolic stiffness), and this effect was also reversed by ranolazine (CV Therapeutics, unpublished data). This finding shows that ranolazine reverses the ATX-II-induced increase in extravascular compression and may account for the effect of ranolazine to maintain coronary flow near normal levels during exposure to ATX-II. An increase in extravascular compression is an important contributor to the decrease in myocardial blood flow when LV wall tension is increased during demand-induced ischaemia.4 Thus, ranolazine significantly reduces the LV mechanical dysfunction due to the sustained rises in diastolic and systolic [Ca2+]i caused by ATX-II.94 These data are consistent with the findings that ranolazine attenuates LV diastolic dysfunction caused by [Na+]i-dependent calcium overload during ischaemia/reperfusion57 in the presence of ischaemic metabolites,68 in the presence of reactive oxygen species69 and in ventricular myocytes from dogs with ischaemic heart failure.75

CONCLUSION

Impaired inactivation of INa increases late INa, leading to increased [Na+]i. The increase of [Na+]i leads to cellular calcium overload. Calcium overload is arrhythmogenic and causes abnormal LV relaxation and diastolic dysfunction. Strong evidence supports the hypothesis that ranolazine suppresses late INa and by this action reduces intracellular calcium overload and [Na+]i-dependent calcium-mediated arrhythmias and LV diastolic dysfunction. Ranolazine improves diastolic function without decreasing systolic function, because ranolazine does not reduce either the peak inward sodium current or the peak inward calcium current.

Abbreviations

APD - action potential duration

[Ca2+]i - intracellular calcium concentration

EAD - early afterdepolarisation

ICa - L, L-type calcium current

IKr - potassium rapid delayed-rectifier current

INa - sodium current

INa - Ca, sodium-calcium exchange current

[Na+]i - intracellular sodium concentration

LV - left ventricular

NCX - sodium-calcium exchanger

NHE - sodium-hydrogen exchanger

+Vmax - maximum upstroke velocity of phase 0 of the action potential

Footnotes

All authors are full-time employees of CV Therapeutics, Inc, which has ownership of intellectual property rights for ranolazine

References

- 1.Ver D L, Borgers M, Verdonck F. Inhibition of sodium and calcium overload pathology in the myocardium: a new cytoprotective principle. Cardiovasc Res 199327349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Noble D, Noble P J. Late sodium current in the pathophysiology of cardiovascular disease: consequences of sodium–calcium overload. Heart 200692(suppl IV)iv1–iv5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Houser S R. Can novel therapies for arrhythmias caused by spontaneous sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release be developed using mouse models? Circ Res 2005961031–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bache R J, Vrobel T R, Arentzen C E.et al Effect of maximal coronary vasodilation on transmural myocardial perfusion during tachycardia in dogs with left ventricular hypertrophy. Circ Res 198149742–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bers D M, Barry W H, Despa S. Intracellular Na+ regulation in cardiac myocytes. Cardiovasc Res 200357897–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pieske B, Houser S R. [Na+]i handling in the failing human heart. Cardiovasc Res 200357874–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eng S, Maddaford T G, Kardami E.et al Protection against myocardial ischemic/reperfusion injury by inhibitors of two separate pathways of Na+ entry. J Mol Cell Cardiol 199830829–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eigel B N, Hadley R W. Contribution of the Na+ channel and Na+/H+ exchanger to the anoxic rise of [Na+] in ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol 1999277H1817–H1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xiao X H, Allen D G. Role of Na+/H+ exchanger during ischemia and preconditioning in the isolated rat heart. Circ Res 199985723–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Avkiran M. Basic biology and pharmacology of the cardiac sarcolemmal sodium/hydrogen exchanger. J Card Surg 2003183–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bielen F V, Bosteel S, Verdonck F. Consequences of CO2 acidosis for transmembrane Na+ transport and membrane current in rabbit cardiac Purkinje fibres. J Physiol (Lond) 1990427325–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Putney L K, Denker S P, Barber D L. The changing face of the Na+/H+ exchanger, NHE1: structure, regulation, and cellular actions. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 200242527–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leem C H, Lagadic-Gossmann D, Vaughan-Jones R D. Characterization of intracellular pH regulation in the guinea-pig ventricular myocyte. J Physiol (Lond) 1999517159–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Orlowski J, Grinstein S. Diversity of the mammalian sodium/proton exchanger SLC9 gene family. Pflugers Arch Eur J Physiol 2004447549–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baetz D, Bernard M, Pinet C.et al Different pathways for sodium entry in cardiac cells during ischemia and early reperfusion. Mol Cell Biochem 2003242115–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stein W D. Cell volume homeostasis: ionic and nonionic mechanisms: the sodium pump in the emergence of animal cells. Int Rev Cytol 2002215231–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cross H R, Radda G K, Clarke K. The role of Na+/K+ ATPase activity during low flow ischemia in preventing myocardial injury: a 31P, 23Na and 87Rb NMR spectroscopic study. Magn Reson Med 199534673–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Despa S, Islam M A, Weber C R.et al Intracellular Na+ concentration is elevated in heart failure but Na/K pump function is unchanged. Circulation 20021052543–2548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hodgkin A L, Katz B. The effect of sodium ions on the electrical activity of the giant axon of the squid. J Physiol (Lond) 194910837–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu Y, DeFelice L J, Mazzanti M. Na channels that remain open throughout the cardiac action potential plateau. Biophys J 199263654–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li C - Z, Wang X - D, Wang H - W.et al Four types of late Na channel current in isolated ventricular myocytes with reference to their contribution to the lastingness of action potential plateau. Acta Physiol Sinica 199749241–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clancy C E, Tateyama M, Liu H.et al Non-equilibrium gating in Na+ channels: an original mechanism of arrhythmia. Circulation 20031072233–2237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kiyosue T, Arita M. Late sodium current and its contribution to action potential configuration in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. Circ Res 198964389–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gintant G A, Datymer N B, Cohen I S. Slow inactivation of texrodotroxin-sensitive current in canine cardiac Purkinje fibers. Biophys J 198445509–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saint D A, Ju Y K, Gage P W. A persistent sodium current in rat ventricular myocytes. J Physiol (Lond) 1992453219–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wasserstrom J A, Salata J J. Basis for tetrodotoxin and lidocaine effects on action potentials in dog ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol 1988254H1157–H1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zygmunt A C, Eddlestone G T, Thomas G P.et al Larger late sodium conductance in M cells contributes to electrical heterogeneity in canine ventricle. Am J Physiol 2001281H689–H697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Antzelevitch C, Shimizu W, Yan G - Z.et al The M cell: its contribution to the ECG and to normal and abnormal electrical function of the heart. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 1999101124–1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shimizu W, Antzelevitch C. Cellular basis for long QT, transmural dispersion of repolarization, and torsade de pointes in the long QT syndrome. J Electrocardiol 199932(Suppl)177–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Valdivia C R, Chu W W, Pu J.et al Increased late sodium current in myocytes from a canine heart failure model and from failing human heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol 200538475–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Belardinelli L, Antzelevitch C, Fraser H. Inhibition of late (sustained/persistent) sodium current: a potential drug target to reduce intracellular sodium-dependent calcium overload and its detrimental effects on cardiomyocyte function. Eur Heart J 20046(Suppl I)13–17. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ju Y K, Saint D A, Gage P W. Hypoxia increases persistent sodium current in rat ventricular myocytes. J Physiol (Lond) 1996497337–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu J, Corr P B. Palmitoyl carnitine modifies sodium currents and induces transient inward current in ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol 1994266H1034–H1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Undrovinas A I, Fleidervish I A, Makielski J C. Inward sodium current at resting potentials in single cardiac myocytes induced by the ischemic metabolite lysophosphatidylcholine. Circ Res 1992711231–1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ward C A, Giles W R. Ionic mechanism of the effects of hydrogen peroxide in rat ventricular myocytes. J Physiol (Lond) 1997500631–642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Undrovinas A I, Maltsev V A, Sabbah H N. Repolarization abnormalities in cardiomyocytes of dogs with chronic heart failure: role of sustained inward current. Cell Mol Life Sci 199955494–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maltsev V A, Sabbah H N, Higgins R S.et al Novel, ultraslow inactivating sodium current in human ventricular cardiomyocytes. Circulation 1998982545–2552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang B, El-Sherif T, Gidh-Jain M.et al Alterations of sodium channel kinetics and gene expression in the postinfarction remodeled myocardium. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 200112218–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Conforti L, Tohse N, Sperelakis N. Tetrodotoxin-sensitive sodium current in rat fetal ventricular myocytes: contribution to the plateau phase of action potential. J Mol Cell Cardiol 199325159–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sakmann B, Spindler A J, Bryant S M.et al Distribution of a persistent sodium current across the ventricular wall in guinea pigs. Circ Res 200087910–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Song Y, Shryock J C, Wu L.et al Antagonism by ranolazine of the pro-arrhythmic effects of increasing late INa in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 200444192–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Le Grand B, Coulombe A, John G W. Late sodium current inhibition in human isolated cardiomyocytes by R56865. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 199831800–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bennett P B, Yazawa K, Makita N.et al Molecular mechanism for an inherited cardiac arrhythmia. Nature 1995376683–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stühmer W, Conti F, Suzuki H.et al Structural parts involved in activation and inactivation of the sodium channel. Nature 1989339597–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vassilev P M, Scheuer T, Catterall W A. Identification of an intracellular peptide segment involved in sodium channel inactivation. Science 19882411658–1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Haigney M C P, Lakatta E G, Stern M D.et al Sodium channel blockade reduces hypoxic sodium loading and sodium-dependent calcium loading. Circulation 199490391–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Van Emous J G, Nederhoff M G, Ruigrok T J.et al The role of the Na+ channel in the accumulation of intracellular Na+ during myocardial ischemia: consequences for post-ischemic recovery. J Mol Cell Cardiol 19972985–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zeitz O, Maass E, Van Nguyen P.et al Hydroxyl radical-induced acute diastolic dysfunction is due to calcium overload via reverse-mode Na+-Ca2+ exchange. Circ Res 200290988–995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Silverman H S, Stern M D. Ionic basis of ischaemic cardiac injury: insights from cellular studies. Cardiovasc Res 199428581–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eigel B N, Hadley R W. Antisense inhibition of Na+/Ca2+ exchange during anoxia/reoxygenation in ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol 2001281H2184–H2190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schäfer C, Ladilov Y, Inserte J.et al Role of the reverse mode of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger in reoxygenation-induced cardiomyocyte injury. Cardiovasc Res 200151241–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Allely M C, Alps B J, Kilpatrick A T. The effects of the novel anti-anginal agent RS-43285 on [lactic acid], [K+] and pH in a canine model of transient myocardial ischemia. Biochem Soc Trans 1987151057–1058. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Allely M C, Alps B J. A comparison of the effects of a series of anti-anginal agents in a novel canine model of transient myocardial ischemia. Br J Pharmacol 198996977–985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Allely M C, Alps B J. Prevention of myocardial enzyme release by ranolazine in a primate model of ischemia with reperfusion. Br J Pharmacol 1990995–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Black S C, Gralinski M R, McCormack J G.et al Effect of ranolazine on infarct size in a canine model of regional myocardial ischemia/reperfusion. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 199424921–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hayashida W, van Eyll C, Rousseau M F.et al Effects of ranolazine on left ventricular diastolic function in patients with ischemic heart disease. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 19948741–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gralinski M R, Black S C, Kilgore K S.et al Cardioprotective effects of ranolazine (RS-43285) in the isolated perfused rabbit heart. Cardiovasc Res 1994281231–1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McCormack J G, Barr R L, Wolff A A.et al Ranolazine stimulates glucose oxidation in normoxic, ischemic, and reperfused ischemic rat hearts. Circulation 199693135–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gralinski M R, Chi L, Park J L.et al Protective effects of ranolazine on ventricular fibrillation induced by activation of the ATP-dependent potassium channel in the rabbit heart. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther 19961141–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.MacInnes A, Fairman D A, Binding P.et al The antianginal agent trimetazidine does not exert its functional benefit via inhibition of mitochondrial long-chain 3-ketoacyl coenzyme A thiolase. Circ Res 200393e26–e32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tavazzi L. Ranolazine, a new antianginal drug. Future Cardiol 200511–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chaitman B R, Pepine C J, Parker J O, for the Combination Assessment of Ranolazine In Stable Angina (CARISA) Investigators et al Effects of ranolazine with atenolol, amlodipine, or diltiazem on exercise tolerance and angina frequency in patients with severe chronic angina: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2004291309–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chaitman B R, Skettino S L, Parker J O, for the MARISA Investigators et al Anti-ischemic effects and long-term survival during ranolazine monotherapy in patients with chronic severe angina. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004431375–1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Clarke B, Spedding M, Patmore L.et al Protective effects of ranolazine in guinea-pig hearts during low-flow ischemia and their association with increases in active pyruvate dehydrogenase. Br J Pharmacol 1993109748–750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Clarke B, Wyatt K M, McCormack J G. Ranolazine increases active pyruvate dehydrogenase in perfused normoxic rat hearts: evidence for an indirect mechanism. J Mol Cell Cardiol 199628341–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.McCormack J G, Barr R L, Wolff A A.et al Ranolazine stimulates glucose oxidation in normoxic, ischemic, and reperfused ischemic rat hearts. Circulation 199693135–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stanley W C. Myocardial energy metabolism during ischemia and the mechanisms of metabolic therapies. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther 20049(Suppl 1)S31–S45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Maruyama K, Hara A, Hashizume H.et al Ranolazine attenuates palmitoyl-L-carnitine-induced mechanical and metabolic derangement in the isolated, perfused rat heart. J Pharm Pharmacol 200052709–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Matsumura H, Hara A, Hashizume H.et al Protective effects of ranolazine, a novel anti-ischemic drug, on the hydrogen peroxide-induced derangements in isolated, perfused rat heart: comparison with dichloroacetate. Jpn J Pharmacol 19987731–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chandler M P, Stanley W C, Morita H.et al Short-term treatment with ranolazine improves mechanical efficiency in dogs with chronic heart failure. Circ Res 200291278–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Antzelevitch C, Belardinelli L, Zygmunt A C.et al Electrophysiological effects of ranolazine, a novel antianginal agent with antiarrhythmic properties. Circulation 2004110904–910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Maltsev V A, Sabbah H N, Undrovinas A I. Late sodium current is a novel target for amiodarone: studies in failing human myocardium. J Mol Cell Cardiol 200133923–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kozhevnikov D O, Dhalla A, Shryock J.et al Ranolazine reverses the changes in cardiac depolarization-repolarization patterns caused by E-4031 and ATX-II: an optical mapping study using experimental models of LQT-2 and LQT-3 syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol 20054581A [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schram G, Zhang L, Derakhchan K.et al Ranolazine: ion-channel-blocking actions and in vivo electrophysiological effects. Br J Pharmacol 20041421300–1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Undrovinas A I, Undrovinas N A, Belardinelli L.et al Ranolazine inhibits late sodium current in isolated left ventricular myocytes of dogs with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 200443178A [Google Scholar]

- 76.Antzelevitch C, Belardinelli L, Wu L.et al Electrophysiologic properties and antiarrhythmic actions of a novel antianginal agent. J Cardiovasc PharmacolTher20049(Suppl I)S65–S83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.CV Therapeutics Ranexa (ranolazine) FDA review documents. NDA 21–526. Palo Alto: CV Therapeutics, 2003

- 78.Bers D M. Cardiac excitation-contraction coupling. Nature 2002415198–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Katra R P, Laurita K R. Cellular mechanism of calcium-mediated triggered activity in the heart. Circ Res 200596535–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pogwizd S M, Schlotthauer K, Li L.et al Arrhythmogenesis and contractile dysfunction in heart failure: roles of sodium-calcium exchange, inward rectifier potassium current, and residual β-adrenergic responsiveness. Circ Res 2001881159–1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Belardinelli L, Antzelevitch C, Vos M A. Assessing predictors of drug-induced torsade de pointes. Trends Physiol Sci 200324619–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Thomsen M B, Verduyn S C, Stengl M.et al Increased short-term variability of repolarization predicts d-sotalol-induced torsades de pointes in dogs. Circulation 20041102453–2459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wu L, Shryock J C, Song Y.et al Antiarrhythmic effects of ranolazine in a guinea pig in vitro model of long-QT syndrome. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2004310599–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wu L, Shryock J C, Song Y.et al An increase in late sodium current potentiates the proarrhythmic activities of low-risk QT-prolonging drugs in female rabbit hearts. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2006316718–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Li G R, Lau C P, Ducharme A.et al Transmural action potential and ionic current remodeling in ventricles of failing canine hearts. Am J Physiol 2002283H1031–H1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Shimizu W, Antzelevitch C. Cellular and ionic basis for T-wave alternans under long-QT conditions. Circulation 1999991499–1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zaniboni M, Pollard A E, Yang L.et al Beat-to-beat repolarization variability in ventricular myocytes and its suppression by electrical coupling. Am J Physiol 2000278H677–H687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sabbah H N, Chandler M P, Mishima T.et al Ranolazine, a partial fatty acid oxidation (pFOX) inhibitor, improves left ventricular function in dogs with chronic heart failure. J Card Fail 20028416–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chen C C, Morishige N, Masuda M.et al R56865, a Na+- and Ca2+-overload inhibitor, reduces myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury in blood-perfused rabbit hearts. J Mol Cell Cardiol 1993251445–1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Le Grand B, Vie B, Talmant J M.et al Alleviation of contractile dysfunction in ischemic hearts by slowly inactivating Na+ current blockers. Am J Physiol 1995269H533–H540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hara A, Arakawa J, Hashizume H.et al Beneficial effects of dilazep on the palmitoyl-L-carnitine-induced derangements in isolated, perfused rat heart: comparison with tetrodotoxin. Jpn J Pharmacol 199774147–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Fraser H, Ivey P E, Kato J.et al Ranolazine reduces ATX-II-induced contracture in rat left atria. In: 25th European Section Meeting. International Society for Heart Research, Bologna, Italy: Medimond 200527–32.

- 93.Fraser H, McVeigh J J, Belardinelli L. Inhibition of late INa by ranolazine improves left ventricular relaxation in a model of Na+-induced Ca2+ overload. Eur Heart J 200526(suppl I)150 [Google Scholar]

- 94.Fraser H, Belardinelli L, Wang L.et al Inhibition of late INa by ranolazine reduces Ca2+ overload and LV mechanical dysfunction in ejecting rat hearts. Eur Heart J 200526(suppl I)414 [Google Scholar]