Idiopathic giant‐cell myocarditis (IGCM) is a rare and highly malignant form of inflammatory heart disease of unknown origin. Pathognomonic histological features are the presence of multinucleated giant cells and a widespread lymphocytic inflammatory infiltration in association with myocyte necrosis.1 IGCM predominantly affects previously healthy young and middle‐aged people. Association with autoimmune disorders has been described in 19% of cases.2

Clinically, IGCM often shows a rapid onset of symptoms followed by a fulminant course resulting in congestive heart failure, progressive heart block and ventricular arrhythmias. The response to treatment is poor, and affected patients are often referred to cardiac transplantation.2

Although IGCM is highly associated with ventricular tachycardia,3 the features of ventricular arrhythmias have not been dealt with. We characterise the type of ventricular tachycardias, the recognition of which might initiate measures to promptly diagnose and treat IGCM.

Methods

Clinical, electrocardiographic, echocardiographic and histopathological data were extracted from the medical records of nine patients diagnosed with IGCM in Helsinki University Hospital, Helsinki, Finland, between 1991 and 2004.

On the basis of electrocardiographic recordings and intracardiac electrophysiological studies, ventricular tachycardias were classified as monomorphic or polymorphic, and the morphological pattern of monomorphic ventricular tachycardia was categorised as right bundle branch block (RBBB) or left bundle branch block (LBBB), and superior or inferior axis in the frontal plane. In electrophysiological studies, programmed ventricular stimulation was carried out from two right ventricular sites using two drive cycle lengths and up to three extra stimuli.

A cardiac pathologist (AR‐S) re‐evaluated all histological samples using the criteria of IGCM.1 Left ventricular ejection fraction was determined by echocardiography or cineangiography.

Results

Table 1 shows the clinical characteristics and course of the nine patients. At the time of diagnosis, the PR interval was <200 ms in five patients. First‐degree atrioventricular block was seen in two patients on admission, and in two patients during progression of the disease. Two patients had QRS duration ⩾120 ms and seven had at least partial bundle branch block, with complete atrioventricular dissociation developing in one patient. In one patient, the electrocardiogram showed marked Q‐waves and persistent ST‐segment elevation in anterior leads (V2–V5) mimicking infarct scar and left ventricular aneurysm. Arteriography showed normal coronary arteries. The diagnosis of IGCM was confirmed in all the patients by histological samples.

Table 1 Clinical characteristics and clinical course of the nine patients.

| Age (years)/sex | Clinical presentation | Time from symptom onset to diagnosis (weeks) | Comorbidities | LVEF (%) at recognition of ventricular arrhythmia | Response of arrhythmia to medical therapy | Time from diagnosis to heart transplantation (months) | Follow‐up time from diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 65/Female | Chest pain | 2 | History of breast cancer | 30 | No VT recurrence | – | 7 months |

| 51/Female | Dyspnoea | 12 | None | 30% | Recurrent VT | 11 | 13 months |

| 52/Female | VT | 104 | None | 60 | No VT recurrence | – | 36 months |

| 44/Male | VT | 52 | None | 17 | No VT recurrence | 0 | 36 months |

| 46/Male | VT | 8 | None | 60 | Recurrent VT | 12 | Died 4 days after HTX |

| 29/Female | Dyspnoea | 2 | Orbital polymyositis | 20 | Recurrent VT | 1 | Died 38 days after HTX |

| 31/Female | VT | 16 | None | 36 | Recurrent VT | 0 | 70 months |

| 47/Male | Dyspnoea | 8 | None | 15 | Recurrent VT | 1 | 162 months |

| 47/Female | VT | 20 | None | 45 | No VT recurrence | – | 1 month |

HTX, heart transplantation; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

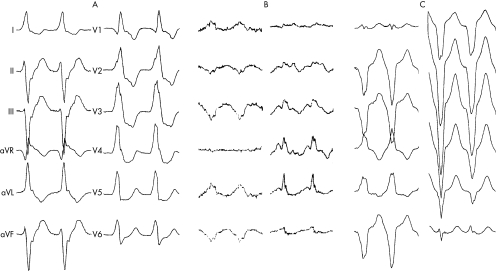

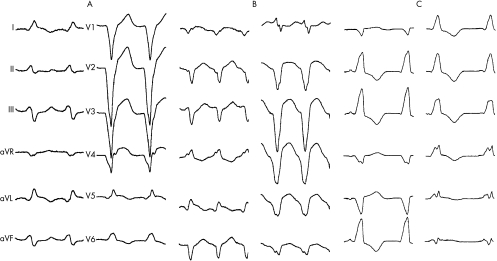

Spontaneous sustained monomorphic ventricular tachycardia occurred in all patients. Five patients presented with monomorphic ventricular tachycardia. Three patients had monomorphic ventricular tachycardia shortly after admission and one had ventricular fibrillation as first documented arrhythmia. The number of different ventricular tachycardia morphologies ranged from 1–6, with median as 3 (mean 3) per patient. Of the 27 different ventricular tachycardia morphologies, 9 showed RBBB pattern (fig 1), with additional superior axis in 3 and inferior axis in 3 patients; 17 tachycardias showed LBBB pattern (fig 2), with superior axis in 7 and inferior axis in 5 patients. One recurrent tachycardia was polymorphic. Of the five patients undergoing electrophysiological studies, four had induced ventricular tachycardias. The heart rate in ventricular tachycardias ranged from 100 to 200 beats/min and was 155 beats/min on average. QRS duration during ventricular tachycardia ranged from 120 to 200 ms and was 157 ms on average. QRS duration was ⩽150 ms in 13 (48%) of the ventricular tachycardias.

Figure 1 Electrocardiograms of spontaneous arrhythmias in patient 5 showing multiple forms of monomorphic ventricular tachycardia. (A) Right bundle branch block (RBBB) pattern and superior axis, rate 130 beats/min. (B) RBBB pattern and superior axis, rate 180 beats/min. (C) Left bundle branch block (LBBB) pattern and superior axis, rate 160 beats/min.

Figure 2 Arrhythmias in patient 7 showing different morphologies of ventricular tachycardias (VT). (A) Left bundle branch block (LBBB) pattern and superior axis, rate 130 beats/min. (B) LBBB pattern and superior axis, rate 180 beats/min. (C) Right bundle branch block (RBBB) pattern and inferior axis, rate 120 beats/min.

β‐adrenergic antagonists and amiodarone were initiated as anti‐arrhythmic treatments concurrently with immunosuppressive therapy. A cardioverter‐defibrillator was implanted in three patients. Ventricular arrhythmias recurred in five patients. Two patients had episodes of ventricular fibrillation at the end stage of the disease.

As a bridge to heart transplantation, two patients were treated with a ventricular assist device. Cardiac transplantation was carried out in six patients. Two of these patients died as a result of bleeding and multiple‐organ failure. Subsequent biopsies during follow‐up of the remaining seven patients have shown no recurrence of IGCM.

Discussion

The characteristics of ventricular arrhythmias in IGCM have not been previously described, although their presence is well recognised.2,3 In the largest published series comprising 63 patients,2 14% presented with ventricular arrhythmias. In our series, most of the patients presented with sustained monomorphic ventricular tachycardia. Arrhythmias showed frequent recurrences and required urgent measures to bring them under control.

At recognition of ventricular arrhythmias, most of our patients had depressed cardiac function but, insidiously, cardiac function was normal in two patients. Typical for ventricular arrhythmias were sustained nature, moderate QRS width and pleomorphism—that is, the presence of multiple morphological patterns in a person. The tachycardia rate was relatively slow, thus not necessarily resulting in haemodynamic compromise. With the progression of IGCM, the ventricular arrhythmias became more malignant and atrioventricular conduction disorders worsened.

Sustained monomorphic nature and inducibility in programmed stimulation suggest that ventricular tachycardias in IGCM are based on a re‐entrant mechanism. Increased myocardial fibrosis and separated myocardial strands, which are observed in histological samples of inflammatory heart disease,4 may provide substrate for unidirectional block and re‐entry. The common appearance of atrioventricular conduction abnormalities also support the view that slow conduction could be present to favour re‐entry. Pleomorphism has been related to different sites of origin and to variation in tachycardia wavefront propagation after myocardial infarction and other aetiologies.5

Our study indicates that sustained ventricular tachycardia can occur early in the course of IGCM, and implies the need to urgently diagnose the underlying heart disease. The disease can also mimic recent myocardial infarction, as seen in our series and previously.2 Finding IGCM as underlying disease should lead to protection with implantable cardioverter‐defibrillator even when the presenting ventricular tachycardias are haemodynamically tolerable.

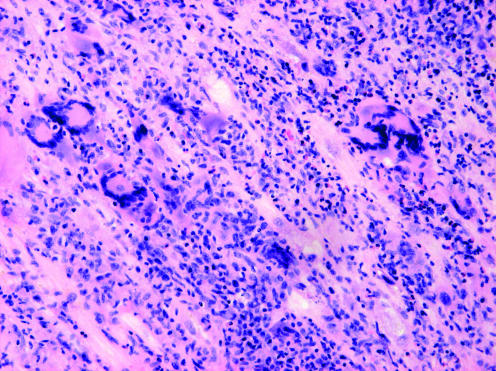

Endomyocardial biopsy is necessary for the diagnosis of IGCM (fig 3) and should be considered for patients with recent onset left ventricular dysfunction and pleomorphic ventricular tachycardias. The prognosis of IGCM is poor, with immunosuppressive therapy giving some benefit, but cardiac transplantation remaining the only possibility for long‐term survival.2

Figure 3 Endomyocardial biopsy specimen from patient 1 showing multinucleated giant cells and extensive lymphocytic infiltration in the myocardium.

In conclusion, IGCM ventricular arrhythmias may appear even before any ventricular dysfunction is obvious. The possibility of IGCM should be considered, particularly if a patient develops multiple forms of monomorphic ventricular tachycardias with relatively slow heart rate. Unless a disorder commonly associated with ventricular tachycardias is recognised, prompt diagnostic evaluation using endomyocardial biopsy is warranted.

Abbreviations

IGCM - idiopathic giant cell myocarditis

LBBB - left bundle branch block

RBBB - right bundle branch block

References

- 1.Okura Y, Dec G W, Hare J M.et al A clinical and histopathologic comparison of cardiac sarcoidosis and idiopathic giant cell myocarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol 200341322–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cooper L T, Jr, Berry G J, Shabetai R. Idiopathic giant‐cell myocarditis–natural history and treatment. Multicenter Giant Cell Myocarditis Study Group Investigators. N Engl J Med 19973361860–1866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davidoff R, Palacios I, Southern J.et al Giant cell versus lymphocytic myocarditis. A comparison of their clinical features and long‐term outcomes. Circulation 199183953–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hsia H H, Marchlinksi F E. Characterization of the electroanatomic substrate for monomorphic ventricular tachycardia in patients with nonischemic cardiomyopathy. Pacing clin Electrophysiol 2002251114–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kimber S K, Downar E, Harris L.et al Mechanisms of spontaneous shift of surface electrocardiographic configuration during ventricular tachycardia. J Am Coll Cardiol 1994201397–1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]