Abstract

The classic definition of cardiac syndrome X (CSX) seems inadequate both for clinical and research purposes and should be replaced with one aimed at including a sufficiently homogeneous group of patients with the common plausible pathophysiological mechanism of coronary microvascular dysfunction. More specifically, CSX should be defined as a form of stable effort angina, which, according to careful diagnostic investigation, can reasonably be attributed to abnormalities in the coronary microvascular circulation.

The classic definition of cardiac syndrome X (CSX) is angina‐like pain on effort, ST segment depression on exercise stress test and totally normal coronary arteries at angiography in the absence of any other cardiac or systemic diseases (for example, hypertension or diabetes) known to influence vascular function.1

Although the origin of the syndrome is still debated, several studies have suggested that CSX is mainly caused by coronary microvascular dysfunction, and indeed the term is often used as a synonym for microvascular angina.

The usual definition of CSX, however, seems inadequate both for clinical and research purposes. Indeed, it does not encompass all patients with microvascular angina and, in the medical literature, it is often discussed interchangeably with the broader syndrome of “chest pain and normal coronary arteries”, which, however, includes more heterogeneous groups of patients. At the same time, some patients with diagnosed CSX may not have any coronary microvascular abnormality.

For these reasons the usual definition of CSX should be abandoned and replaced with one aimed at including a sufficiently homogeneous group of patients with the common plausible pathophysiological mechanism of coronary microvascular dysfunction. More specifically, CSX should be defined as a form of stable effort angina, which, according to careful diagnostic investigation, can reasonably be attributed to abnormalities in the coronary microvascular circulation.

Accordingly, CSX should be diagnosed in the presence of the following findings (table 1): (1) angina episodes ensuing exclusively or predominantly on effort and typical enough to suggest coronary artery disease (CAD); (2) findings compatible with myocardial ischaemia or coronary blood flow (CBF) abnormalities during spontaneous or provoked angina; (3) normal (or near normal) coronary arteries at angiography; (4) absence of other specific forms of cardiac disease (for example, variant angina, cardiomyopathies and valvular heart disease).

Table 1 Proposed definition of cardiac syndrome X.

| • Typical stable angina, exclusively or predominantly induced by effort |

| • Findings compatible with myocardial ischaemia/coronary microvascular dysfunction on diagnostic investigation* |

| • Normal (or near normal†) coronary arteries at angiography |

| • Absence of any other specific cardiac disease (for example, variant angina, cardiomyopathy, valvular disease) |

*Including one or more of (1) diagnostic ST segment depression during spontaneous or stress‐induced typical chest pain; (2) reversible perfusion defects on stress myocardial scintigraphy; (3) documentation of stress‐related coronary blood flow abnormalities by more advanced diagnostic techniques (for example, cardiac magnetic resonance (MR), positron emission tomography (PET) or Doppler ultrasound); (4) metabolic evidence of transient myocardial ischaemia (cardiac PET or MR, invasive assessment).

†Vascular wall irregularities or discrete very mild stenosis (<20%) in epicardial vessels at angiography.

The differences between this and the usual definition of CSX merit some comments. Firstly, in the proposed definition, exercise‐induced ST segment depression is not required; indeed, as in patients with obstructive CAD, exercise ECG may be negative in patients with coronary microvascular disease, whereas findings compatible with myocardial ischaemia can be detected by other diagnostic techniques (for example, ST segment changes during ECG Holter monitoring or pharmacological stress tests; reversible perfusion defects during stress myocardial scintigraphy). On the other hand, clinicians should be careful in excluding from the diagnosis patients with exercise‐induced ST segment depression who clearly have atypical or non‐cardiac chest pain when no other evidence of microvascular dysfunction can be obtained.

Secondly, patients with hypertension and diabetes are not excluded from the definition. These patients have, indeed, often been included in studies on patients with angina and normal coronary arteries, and patients included in studies on classic CSX often had borderline or mild hypertension, glucose intolerance or insulin resistance; furthermore, hypertensive patients with normal coronary arteries have been reported to have stress test results similar to those of typical patients with CSX.2 Lastly, hypertension and diabetes were previously excluded from CSX, as they were known risk factors for microvascular abnormalities, whereas CSX was intended as a form of “idiopathic microvascular dysfunction”. However, it is now clear that CAD risk factors, including hypercholesterolaemia, obesity, smoking and low‐grade inflammation, may all cause microvascular dysfunction in the absence of coronary atherosclerosis, mainly as a result of endothelial dysfunction. These CAD risk factors are often present in patients with CSX and probably contribute to the microvascular abnormality. Accordingly, hypertension and diabetes should also be considered to be risk factors for microvascular dysfunction in CSX, as they are for obstructive CAD.

Some patients with CSX, in fact, have no apparent CAD risk factors and microvascular dysfunction seems to be caused by unknown mechanisms. This is not surprising, however, as up to 15–20% of patients with obstructive CAD also have no apparent risk factor.

A further point of the proposed definition of CSX concerns patients with minor atherosclerotic lesions (that is, irregularities or very mild stenosis of < 20%) in epicardial vessels at angiography. The inclusion of these patients is justified by the fact that these abnormalities cannot be responsible for angina symptoms, that some degree of coronary atherosclerosis may also be found by intracoronary ultrasound imaging in a proportion of patients with classic CSX,3 and that their clinical outcome seems similar to that of patients with classic CSX.

Finally, it should be stressed that coronary microvascular abnormalities may be involved in angina syndromes other than CSX, including angina after successful percutaneous coronary interventions, microvascular vasospastic angina and some cases of non‐ST elevation acute coronary syndromes with normal coronary arteries. These conditions have distinct clinical features and different possible mechanisms. Thus, they should be kept separate from CSX.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGIC MECHANISMS

Several studies have shown that patients with CSX have coronary microvascular abnormalities. Other data, on the other hand, point out that abnormal cardiac pain sensitivity also has a significant role in determining the clinical syndrome in most of these patients.

MICROVASCULAR DYSFUNCTION

A major problem in the assessment of coronary microcirculation in humans is that the structure and function of small coronary vessels cannot be studied directly. Thus, attempts to find evidence of coronary microvascular abnormalities in CSX have been based on two major kinds of studies: (1) those assessing the response of CBF or coronary vascular resistance, which strictly depends on microvascular integrity, to vasoactive stimuli; and (2) those aimed at directly showing the occurrence of myocardial ischaemia.

In fact, in some studies, histopathological examination of endomyocardial biopsies has shown structural abnormalities of small coronary arteries in patients with CSX, including medial hypertrophy ad lumen narrowing.4 Overall, however, the data have been discordant and the actual role of structural microvascular alterations remains to be established.

Coronary microvascular response to vasoactive stimuli

Both vasodilator stimuli and vasoconstrictor stimuli have been used to assess coronary microvascular function in patients with CSX. The study of vasodilator function has further concerned the assessment of endothelium‐independent and endothelium‐dependent mechanisms.

Endothelium‐independent vasodilatation

In 1981 Opherk et al5 first reported a reduced CBF response to dipyridamole, an endothelium‐independent arteriolar vasodilator, in CSX. By using the argon washout method, they found that CBF increased 3.8‐fold in controls but only 2.0‐fold in patients with CSX (p < 0.001), thus suggesting an impairment of smooth muscle cell relaxation of small coronary artery vessels.

Since then a large number of studies have confirmed reduced endothelium‐independent coronary microvascular dilatation in patients with CSX, by using different stimuli (dipyridamole, adenosine or papaverine) and methods (thermodilution, intracoronary Doppler recording, positron emission tomography (PET) or cardiac magnetic resonance (MR)) to measure CBF and coronary vascular resistance.1

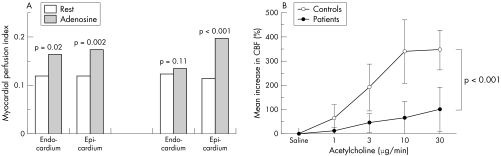

Thus, Bøttcher et al,6 by using PET, showed a reduced CBF increase in response to dipyridamole in 25 women with CSX compared with controls (2.96 (0.63) v 2.03 (0.53), p < 0.01). Panting et al,7 by using cardiac MR, showed that, compared with rest, the myocardial perfusion index in response to adenosine did not increase in the subendocardium in patients with CSX, whereas it did increase in healthy controls (fig 1A).

Figure 1 (A) Change in myocardial perfusion index in subendocardial and subepicardial layers in response to adenosine (140 µg/kg/min), as assessed by gadolinium cardiac magnetic resonance, in a group of 20 patients with cardiac syndrome X and in a group of 10 control subjects. A blunted vasodilator response in the subendocardium is observed in patients with syndrome X. Adapted with permission from Panting et al.7 (B) Increase in coronary blood flow (CBF), as assessed by intracoronary Doppler recording of CBF velocity, in response to increasing doses of intracoronary acetylcholine in a group of nine patients with cardiac syndrome X and in 10 control subjects. A reduced vasodilator response is observed in patients with syndrome X for all doses of acetylcholine. Adapted with permission from Egashira et al.9

Endothelium‐dependent vasodilatation

Endothelium‐dependent coronary microvascular function has mainly been studied by assessing the CBF response to acetylcholine, the vasodilator effect of which is mediated by nitric oxide release by endothelial cells. An impairment of coronary endothelial function in CSX was first suggested by Motz et al,8 who assessed CBF response to intracoronary acetylcholine and to intravenous dipyridamole in 23 such patients. In six patients CBF did not increase significantly in response to both drugs, whereas no significant microvascular dilatation was detectable in response to either acetylcholine (eight patients) or dipyridamole (three patients).

In a subsequent study, Egashira et al9 showed that injection of increasing doses of acetylcholine into the left coronary artery caused a lower dose‐dependent increase in CBF in patients with CSX compared with control subjects with atypical chest pain (fig 1B).

In interpreting these results it should be observed that acetylcholine not only is an endothelium‐dependent vasodilator but also can induce vasoconstriction in susceptible vessels through direct stimulation of muscarinic receptors on smooth muscle cells. Thus, the impaired increase in CBF response may result, at least in some patients, from a combination of reduced endothelium‐dependent vasodilatation and increased vasoconstrictive reactivity of smooth muscle cells (see below).

Data showing that l‐arginine (the substrate for nitric oxide synthesis) and tetrahydrobiopterin (a nitric oxide synthase cofactor) normalised the vasodilator response to acetylcholine in patients with CSX, however, suggest that impaired nitric oxide function is a major cause of the reduced acetylcholine‐mediated vasodilatation in these patients.

Increased vasoconstrictor response

Several studies have suggested that an increased reactivity of small coronary artery vessels to vasoconstrictor stimuli may also have a significant role in CSX.

Cannon et al10 first reported that intravenous ergonovine administration (0.15 mg) facilitated the appearance of chest pain and blunted CBF increase during atrial pacing, compared with atrial pacing alone, in patients with CSX. Furthermore, several studies have shown a CBF reduction in response to intracoronary low‐dose acetylcholine in some patients,8 thus suggesting that an increased vasoconstrictor response may significantly contribute to the abnormal vasomotor response to this substance, at least in some patients (see above).

A decrease in CBF, suggesting coronary microvascular vasoconstriction, was also found in patients with CSX after acid oesophageal stimulation, hyperventilation and mental stress.11

Indirect clues to coronary microvascular dysfunction

Some studies have shown reduced endothelium‐dependent vasodilatation or increased vasoconstriction, or both, in response to various stimuli (for example, exercise, acetylcholine and ergonovine) in epicardial coronary artery vessels12 of patients with CSX. Other studies have found abnormalities in the vascular function of resistance or conductance arteries of the peripheral circulation, mainly involving endothelium‐dependent vasodilatation.13 These findings indirectly support the presence of coronary microvascular abnormalities in CSX, also suggesting that, at least in some patients, coronary microvascular abnormalities are not isolated but are part of a more generalised abnormality of vascular function.

Assessment of myocardial ischaemia

In the classic definition of CSX the basic clue to myocardial ischaemia is the induction of ST segment depression on exercise stress testing. Furthermore, as discussed above, in patients with CSX ST segment depression can also be induced by atrial pacing or ischaemia‐inducing drugs, or it can be detected on ECG Holter monitoring. Moreover, reversible perfusion defects on stress myocardial scintigraphy, compatible with myocardial ischaemia, can be found in about 50%, and up to > 90%, of patients.14

Some authors, however, have questioned the microvascular/ischaemic origin of these findings, objecting that proof of myocardial ischaemia would require evidence of more specific and convincing alterations, including typical metabolic changes and left ventricular (LV) wall motion abnormalities.15

In fact, some studies failed to find metabolic abnormalities indicative of myocardial ischaemia during stress testing.16 A global assessment of published data, however, shows that metabolic evidence of stress‐induced myocardial ischaemia, including myocardial lactate production, coronary sinus oxygen desaturation and coronary sinus pH reduction, has clearly been obtained in at least a subgroup (⩾ 20%) of patients with CSX.1

Notably, in a recent study Buchthal et al,17 by assessing myocardial phosphorus‐31 metabolism by MR spectroscopy, showed typical metabolic ischaemic changes during a handgrip test in about 20% of women with CSX, a proportion similar to that observed in a group of patients with CAD. As the stressor used was mild and only the territory of the left anterior descending artery could be analysed, it can be argued that the proportion of patients with evidence of myocardial ischaemia might have been higher if a more stressful stimulus had been used and other cardiac territories could have been explored.

Impressively, Buffon et al,18 in a group of patients with CSX, found a high level of myocardial release of lipoperoxide products in the coronary circulation after atrial pacing, similar to that found in patients with CAD after coronary occlusion induced by balloon inflation during percutaneous coronary intervention.

LV contractile abnormalities, on the other hand, have consistently been undetectable by two‐dimensional echocardiographic stress tests in patients with CSX.19 Maseri et al,20 however, plausibly explained the difficulty in detecting LV dysfunction, as well as ischaemic metabolites, by the usual diagnostic methods, suggesting that, in patients with CSX, microvascular dysfunction is patchily distributed across the myocardial wall, rather than being diffuse. This implies that reduced LV function in the small involved segments can usually be obscured by the normal, or even increased, function of adjacent interposed myocardial areas. Similarly, ischaemic metabolites released by the small ischaemic areas may not be detected as diluted in the coronary blood draining from normal myocardial areas. This situation contrasts with that of patients with flow‐limiting epicardial stenosis, in whom stress tests induce ischaemia in large subendocardial areas, thus more easily resulting in abnormal LV function and metabolic evidence of ischaemia.

The hypothesis that the microvascular abnormality can be patchily distributed in the myocardium of patients with CSX has been supported by PET studies, which showed a higher heterogeneity in CBF among small myocardial areas after dipyridamole administration in patients with CSX than in healthy controls.21 Accordingly, in their cardiac MR study Panting et al7 showed that in patients with CSX the reduced CBF response to adenosine in subendocardial layers, rather than being diffuse, concerned only 47% of the regions of interest into which the subendocardium was divided.

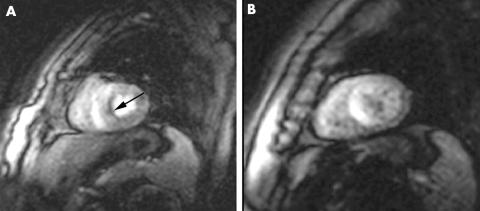

Of note, our group has recently detected dobutamine stress‐induced gadolinium defects on cardiac MR imaging that are compatible with subendocardial ischaemia, despite the absence of LV wall motion abnormalities, in a significant proportion of patients with CSX (fig 2) (unpublished data).

Figure 2 Evidence of subendocardial septal perfusion defect (panel A, arrow) at peak dobutamine infusion (40 µg/kg/min) and its absence at rest (panel B) on gadolinium cardiac magnetic resonance in a patient with cardiac syndrome X. No abnormalities in left ventricular function were detectable.

Mechanisms of microvascular dysfunction

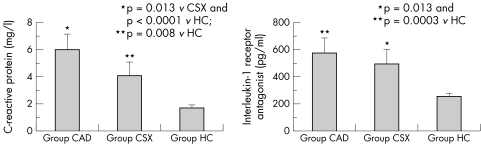

Several abnormal findings that potentially can cause abnormalities in the coronary microcirculation have been described in CSX. As previously observed, traditional cardiovascular risk factors, including hypertension and diabetes, probably contribute to coronary microvascular dysfunction, in particular through impairment of endothelium‐dependent vasodilatation. Furthermore, other abnormalities that can cause endothelial dysfunction have been reported in patients with CSX, including insulin resistance,22 oestrogen deficiency (in women)23 and low‐grade inflammation.24,25 Indeed, we have shown increased blood concentrations of C reactive protein and interleukin 1 receptor antagonist in patients with CSX, compared with matched healthy subjects, with concentrations of interleukin 1 receptor antagonist similar to those of patients with stable CAD24 (fig 3). Some data also suggest a correlation of C reactive protein concentrations with severity of symptoms in patients with CSX.25

Figure 3 Plasma concentrations of C reactive protein and of interleukin 1 receptor antagonist, two markers of inflammation, in 55 patients with cardiac syndrome X (group CSX), in 49 patients with obstructive coronary artery disease (group CAD) and in 60 healthy controls (group HC). Significantly higher concentrations of both CRP and IL‐1Ra were found in patients with CSX, than in controls; of note, IL‐1Ra concentrations were not statistically different between patients with CAD and patients with CSX. Adapted from Lanza et al.24

Abnormal function of the coronary endothelium, however, can not only impair endothelium‐mediated vasodilatation but also increase endothelial vasoconstrictor activity, mainly mediated by endothelin 1 production. Indeed, increased concentrations of endothelin 1 have been reported in patients with CSX and shown to correlate with impaired CBF reserve26; moreover, we have shown a significant increase in endothelin 1 concentrations in the coronary circulation of patients with CSX during atrial pacing, whereas no changes were observed in matched controls.27

Increased adrenergic function has also been suggested to have a pathogenetic role in CSX, and impaired cardiac uptake of metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG), indicating abnormal handling of norepinephrine in cardiac sympathetic nerve endings, has been shown in about 75% of patients.28 Although the exact mechanism responsible for this finding remains to be clarified, it is worth noting that impaired cardiac uptake of the norepinephrine analogue 11C‐hydroxyephedrine in transplanted and in diabetic hearts is associated with a reduced microvascular vasodilator response to cold pressor test,29 suggesting that a similar abnormality may exist in myocardial territories with MIBG defects in patients with CSX.

Lastly, increased membrane Na+/H+ exchanger activity, the major regulator of intracellular pH,30 which can also influence cellular Ca2+ handling and therefore favour vasoconstriction, has also been described in patients with CSX.

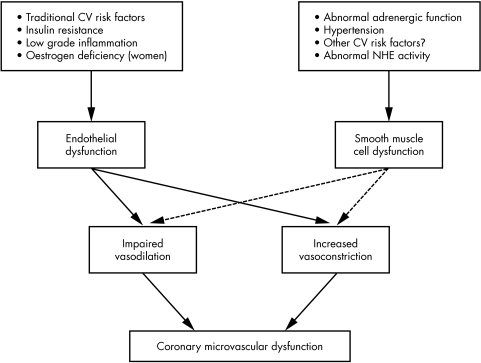

Thus, the mechanisms involved in the microvascular abnormalities in patients with CSX are likely to be multiple and heterogeneous and may result in a variable combination of impaired vasodilator function and increased vasoconstrictor activity, with vasodilator abnormalities variably involving endothelium‐dependent and endothelium‐independent mechanisms (fig 4).

Figure 4 Scheme of the main pathogenetic mechanisms and functional abnormalities that may variably contribute to microvascular dysfunction in patients with cardiac syndrome X, according to data reported in the medical literature. CV, cardiovascular; NHE, Na+/H+ exchanger.

This heterogeneity of causes and microvascular abnormalities may, at least in part, explain some differences in the characteristics of microvascular dysfunction between published studies and may have also contributed to the failure to find evidence of microvascular abnormalities or myocardial ischaemia in some studies; this failure may have variably been related to inadequate patient selection criteria, use of inappropriate diagnostic techniques or stress stimuli and spontaneous variability of the pathophysiological mechanisms responsible for the syndrome.

ABNORMAL CARDIAC PAIN PERCEPTION

In 1988, Shapiro et al31 reported that the mere intra‐atrial injection of saline solution in the right atrium caused chest pain in a group of patients with angina and normal coronary arteries. Subsequently, several studies have consistently shown enhanced pain perception of cardiac stimuli in patients with CSX, including intracardiac catheter manipulation and electrical stimulation.32 Furthermore, the administration of dipyridamole, adenosine and dobutamine often causes severe typical chest pain in these patients, in contrast with the lack of severe ischaemic myocardial pain.

Whether the increased cardiac pain sensitivity is a specific cardiac abnormality or is part of a generalised pain disorder is controversial. Some studies have shown that peripheral stimuli (electrical skin stimulation, cold stimulation, forearm ischaemia and oesophageal stimulation) may cause pain more easily in patients with CSX than in healthy controls, but these findings should be viewed with caution, as the studies were uncontrolled. Indeed, in studies that followed controlled protocols, general pain sensitivity, as assessed by thermal or laser skin stimuli, was not found to be increased in patients with CSX.32,33 On the other hand, in a randomised, double‐blind, sham‐controlled study, we have confirmed that pain can be elicited by low‐rate ventricular pacing in patients with CSX but not in controls, thus clearly showing the presence of increased pain sensitivity to cardiac stimuli.34

The site of the “neural” abnormality responsible for the enhanced cardiac pain perception is also a matter of discussion. Rosen et al35 have shown activation of the right anterior insula cortex in patients with CSX during angina and ST segment depression induced by dobutamine stress test, in the absence of LV wall motion abnormalities, suggesting a cortical origin of the nociceptive abnormality.

Other findings concur to suggest that the abnormality involves cardiac afferent nerve endings, however, including (1) the clinical observation that recurrent chest pain is usually the only kind of pain these patients have; (2) evidence that abnormal pain sensitivity is confined to the heart32,33,34; and (3) evidence of abnormal efferent adrenergic fibre nerve function in the heart but not in other organs (lung, liver and salivary glands).28

We have recently shown, however, that patients with CSX may lack habituation to pain stimuli, which may contribute to the clinical features of chest pain episodes.33 The exact mechanism of this abnormality and the relation with abnormal cardiac nerve function, however, remain to be established.

Relation between coronary microvascular dysfunction and abnormal cardiac pain sensitivity

Whereas microvascular dysfunction, patchily distributed in the myocardium,20 would usually result in mild degrees of subendocardial ischaemia and stable or tolerable symptoms, the presence of increased cardiac pain sensitivity in a sizeable proportion of patients with CSX would predispose them to frequent and severe angina episodes, even for mild degrees of ischaemia.

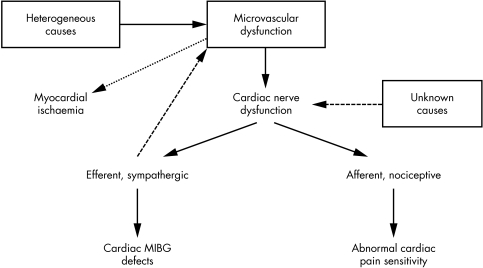

The causes of the abnormal cardiac pain sensitivity and the relationship with the coronary microvascular abnormality, however, remain unknown. We recently hypothesised that enhanced cardiac pain sensitivity may actually be a consequence of microvascular dysfunction, suggesting that repeated subclinical episodes of myocardial ischaemia may alter cardiac nerve fibres involving both afferent endings (resulting in increased response to usually innocuous stimuli) and efferent endings (causing, for example, impaired cardiac MIBG uptake in sympathetic fibres) (fig 5).36

Figure 5 Possible relations between microvascular dysfunction and cardiac nerve ending abnormalities in cardiac syndrome X (CSX). Microvascular dysfunction in patients with CSX may cause repeated episodic reduction of coronary blood flow, which may induce alterations in both efferent and afferent cardiac nerve fibres. The abnormal efferent adrenergic function can be indicated by the reduced uptake of meta‐121iodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) by the heart, whereas abnormalities in afferent cardiac fibres may lead to increased generation and transmission of pain signals (increased cardiac pain perception). Abnormal activity of adrenergic fibres may, in turn, influence microvascular function. Pathological mechanisms different from microvascular dysfunction, however, may be responsible for primary cardiac nerve abnormalities, leading to the same clinical picture. Adapted from Lanza.36

Alternative relationships are clearly possible, however, including (1) a primary abnormality of cardiac nerves (caused, for example, by inflammatory processes), the efferent arm of which may adversely affect microvascular function; (2) a common pathogenetic cause that simultaneously affects coronary microvascular and cardiac nerve function; and (3) a casual independent occurrence of both abnormalities in the same patient.

It should be stressed that in patients with CSX with increased cardiac pain sensitivity, cardiac stimuli other than ischaemia may also cause angina pain. On the other hand, increased cardiac nociception can also be the only cause of angina‐like symptoms in some patients with chest pain and normal coronary arteries, such as the few patients who develop chest pain in relation to intermittent left bundle branch block. In these patients several stimuli, including the physiological cardiac release of adenosine during exercise, may cause chest pain. These patients can be identified by the failure to find any evidence of microvascular dysfunction or ischaemia and by eliciting pain during intracardiac manoeuvres (for example, heart pacing). This group of patients should clearly be excluded from the diagnosis of CSX.

DIAGNOSIS

According to the proposed definition (see above), the diagnosis of CSX would require, together with the presence of typical angina and normal (or near normal) coronary arteries at angiography, some findings compatible with myocardial ischaemia or coronary microvascular dysfunction, or both.

A major diagnostic challenge for the cardiologist, however, is whether patients with CSX can be distinguished with sufficient reliability from those with obstructive CAD on the basis of a careful assessment of clinical findings and non‐invasive investigation, which would avoid subjecting the patient to the small but definite risk associated with coronary angiography and would also have favourable effects on costs and use of medical resources.

General data are of limited diagnostic help in individual patients. Compared with those with obstructive CAD, patients with CSX are more commonly women, in whom angina often appears after menopause (either spontaneous or surgical); however, female patients with CAD are also more likely to have angina symptoms after menopause.

The characteristics of chest pain also do not often permit distinguishing between the two groups of patients. However, the presence of some findings strongly orient the diagnosis towards CSX. These, in particular, are a prolonged (> 15–20 min) dull persistence of chest discomfort after resolution of typical chest pain induced by exercise and a lack of response, or a slow or incomplete response, to administration of short‐acting nitrates to relieve pain, both features occurring in about 50% of patients.37

Among diagnostic stress tests, the careful analysis of abnormal exercise and stress scintigraphic results also does not usually help to identify patients with CSX. In contrast, the induction of typical, often severe angina during echocardiographic stress test (for example, with dipyridamole or dobutamine) in the presence of ST segment depression, but in the absence of LV contractile abnormalities, strongly suggests CSX, although LV dysfunction can also be undetectable in patients with mild forms of CAD.

Repeating exercise testing after giving sublingual nitrates may also help to identify patients with CSX. Indeed, preventive administration of short‐acting nitrates usually improves exercise‐induced ST segment changes and symptoms in patients with CAD, whereas short‐acting nitrates may paradoxically induce earlier ST segment changes during the test in some patients with CSX.38

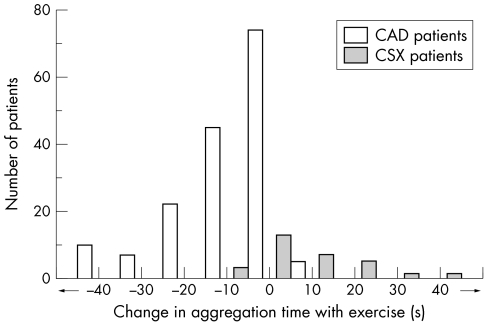

Lastly, although unpractical for clinical use, assessing platelet reactivity in response to ADP/collagen after exercise may provide a further clue to CSX diagnosis in patients with angina. Indeed, by using the platelet function analyser‐100 method, we have recently found that a lengthening by ⩾ 10 s of the aggregation time after exercise (implying a reduction of platelet reactivity) was detectable only in patients with CSX, whereas a reduction ⩾ 10 s (implying an increase of platelet reactivity) was detectable only in patients with CAD (fig 6).39

Figure 6 Distribution of the differences of aggregation times in response to platelet stimulation with collagen/adenosine diphosphate, observed after exercise and at rest, in 163 patients with stable obstructive coronary artery disease (CAD) and in 31 patients with cardiac syndrome X (CSX). About 50% of patients with CSX had significantly lengthened (⩾ 10 s) aggregation time after exercise, compatible with a reduction of platelet reactivity. This pattern was not observed in patients with CAD, most of whom had increased platelet reactivity after exercise. Adapted from Lanza et al.39

Thus, careful clinical and non‐invasive diagnostic assessment of patients with effort angina can find strong clues to the diagnosis of CSX, which may lead to a sufficiently reliable diagnosis of probable CSX, in particular when more suggestive findings are detected together in individual patients.

In the presence of probable CSX, when a definitive diagnosis is required, the preferred test to document the presence of normal coronary arteries should perhaps now be considered to be multislice spiral computed tomography coronary angiography, which has a high negative predictive value for significant CAD (> 95%) and would avoid the small but definite risk of invasive coronary angiography to the patient.

CLINICAL OUTCOME

Only a few studies, with limited numbers of patients, have specifically investigated the long‐term clinical outcome of patients with an accurate diagnosis of CSX at presentation,37 whereas follow up of larger populations of patients has concerned the broader cohort of patients with chest pain and normal coronary arteries or non‐significant CAD. Although an unidentifiable number of study participants might have had CSX, patients included in these latter studies were very heterogeneous, with chest pain likely related to different causes, both cardiac and non‐cardiac. Accordingly, these studies should be considered with caution when trying to define accurately the clinical outcome of patients with CSX.

Prognosis

All studies on patients with CSX have consistently reported an excellent clinical outcome at long‐term follow up, with a total absence of major acute coronary events (that is, cardiac death or acute myocardial infarction).37

The favourable prognosis of patients with CSX can be challenged by some recent data showing increased occurrence of events among patients with chest pain and normal or near normal coronary arteries who had evidence of coronary endothelial dysfunction.40 However, these studies included patients with characteristics (for example, with LV dysfunction or subcritical coronary artery stenoses) clearly different from those of CSX. Thus, these studies cannot be taken as a clue to a possible prognostic value of endothelial dysfunction in patients with CSX. In fact, a recent study showed no spontaneous acute coronary events at the 12‐year follow up of women with CSX who also had evidence of coronary endothelial dysfunction at enrolment.41

Although studies have consistently shown a good prognosis for patients with CSX, no attempts have been made to understand whether this finding may have some specific explanation. Indeed, these patients present a risk profile largely similar to that of patients with obstructive CAD, including, together with a significant prevalence of traditional cardiovascular risk factors, a higher prevalence of inflammation, insulin resistance and endothelial dysfunction.

Thus, a challenging clinical question is whether patients with CSX may have some protective factor that, despite the evidence of coronary microvascular dysfunction, may delay the development of critical atherosclerotic lesions in large coronary vessels and prevent acute coronary events. This possibility is suggested by our data showing a reduction in platelet reactivity after stress stimuli (for example, exercise or mental stress) in patients with CSX, in contrast to patients with CAD and to normal subjects, in whom an increase (fig 6) and no changes in platelet reactivity, respectively, are observed.39,42,43 Whether these findings really imply vascular protection and whether other potential protective factors against acute thrombotic coronary events exist in patients with CSX are challenging issues that would merit investigation in future studies.

Quality of life

In contrast to the excellent prognosis, patients with CSX may have a significantly impaired quality of life. Symptoms improve over time in only about one third of patients. In 10–20% of patients, on the other hand, anginal symptoms worsen progressively during follow up, becoming more frequent and long lasting, ensuing at lower levels of exercise or even at rest and becoming less sensitive or refractory to drug treatment, thus impairing usual daily activities, which also results in high rates of absence and retirement from work.37 The most symptomatic patients also may often have recurrent medical visits, emergency room admissions and hospital admissions, and have repeat non‐invasive diagnostic tests and coronary angiography. Thus, although prognostically benign, CSX is an individually, socially and economically relevant condition.

Although a psychological component has been suggested to be involved in patients with CSX with severe chest pain, it is not clear whether psychological disturbances have a causal role or are rather a consequence of the persistent invalidating symptoms. Some data, indeed, suggest that the prevalence of psychological disorders is similar in patients with CSX and in those with obstructive CAD, thus supporting the second hypothesis (F Creed, personal communication, 2005).

THERAPEUTIC APPROACH

Treatment of patients with CSX has recently been discussed in detail, and we refer the reader elsewhere for a comprehensive review of the topic.1 As major cardiac events are not increased, the main goal of clinical management is the control of symptoms. Accordingly, interventions found to have beneficial effects on chest pain and quality of life in appropriate studies should be preferred to those tested only on surrogate end points, including ischaemic ECG changes or CBF response to vasoactive stimuli.

As the response to treatment is unpredictable, therapeutic management is necessarily empirical and requires an optimal interaction between the caring physician and the patient in the attempt to achieve optimal symptom control. Thus, adequate medical support is crucial for patients with debilitating symptoms, in particular when psychological involvement is evident. An exercise rehabilitation programme can also help to improve effort tolerance in patients with severe symptoms.

According to the most important pathogenetic components, drug treatment in patients with CSX is mainly directed to improve coronary microvascular function or decrease abnormal cardiac pain sensitivity. If β blockers are not contraindicated, we prefer to start treatment with a β blocking agent, although a non‐dihydropyridine calcium antagonist is an alternative choice. A dihydropyridine calcium antagonist or a long‐acting nitrate, or both, can be added as a second line treatment.

Several other drugs have been tried, with variable results, and can be variably added to the classic ischaemia drugs in patients with persisting symptoms. Beneficial effects have been reported, in particular, with xanthine derivatives (which can cause an antialgogenic effect, due to the direct involvement of adenosine in cardiac pain generation, and an anti‐ischaemic effect, due to a favourable redistribution of CBF), imipramine (which inhibits pain transmission from visceral tissues), angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors (on the assumption that the renin–angiotensin system may have a role in causing microvascular dysfunction), α antagonist drugs (which may decrease α‐mediated vasoconstriction), statins and, in postmenopausal women, oestrogens (both of which may improve endothelium‐mediated coronary vasodilatation).

For refractory angina episodes, spinal cord stimulation (which may favourably affect cardiac pain transmission and CBF through modulation of sympathetic efferent nerves) has been reported to be helpful in a significant proportion of patients.

CONCLUSIONS

Several reasons for CSX merit the attention of clinicians and researchers. Firstly, patients with CSX constitute a consistent part (10–20%) of the high number of patients who undergo coronary angiography and often pose important diagnostic and therapeutic problems for cardiologists. Secondly, the study of patients with CSX may help to clarify the pathophysiology of coronary microcirculation and its clinical manifestations, as well as to improve understanding of the mechanisms and pathophysiology of cardiac pain. Lastly, it is time to consider that studying patients with CSX may help to identify favourable characteristics that may be protective factors against the development of obstructive CAD and acute coronary events.

Additional references are available on the Heart website—http://www.heartjnl.com/supplemental

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I thank Professor Filippo Crea for his critical review of the manuscript. Thanks to Dr Gregory A Sgueglia for his assistance in the preparation of the manuscript. I am deeply grateful to Professor Attilio Maseri for his invaluable teachings about ischaemic heart disease.

Abbreviations

CAD - coronary artery disease

CBF - coronary blood flow

CSX - cardiac syndrome X

LV - left ventricular

MIBG - metaiodobenzylguanidine

MR - magnetic resonance

PET - positron emission tomography

Footnotes

Additional references are available on the Heart website—http://www.heartjnl.com/supplemental

References

- 1.Crea F, Lanza G A. Angina pectoris and normal coronary arteries. Heart 200490457–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brush J E, Cannon R O, III, Schenke W H.et al Angina due to coronary microvascular disease in hypertensive patients without left ventricular hypertrophy. N Engl J Med 19883191302–1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wiedermann J G, Schwartz A, Apfelbaum M. Anatomic and physiologic heterogeneity in patients with syndrome X: an intravascular ultrasound study. J Am Coll Cardiol 1995251310–1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mosseri M, Yarom R, Gotsman M S.et al Histologic evidence for small‐vessel coronary artery disease in patients with angina pectoris and patent large coronary arteries. Circulation 198674964–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Opherk D, Zebe H, Weihe E.et al Reduced coronary dilator capacity and ultrastructural changes of the myocardium in patients with angina pectoris but normal coronary arteriograms. Circulation 198163817–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bøttcher M, Bøtker H E, Sonne H.et al Endothelium‐dependent and ‐independent perfusion reserve and the effect of L‐arginine on myocardial perfusion in patients with syndrome X. Circulation 1999991795–1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Panting J R, Gatehouse P D, Yang G Z.et al Abnormal subendocardial perfusion in cardiac syndrome X detected by cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging. N Engl J Med 20023461948–1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Motz W, Vogt M, Rabenau O.et al Evidence of endothelial dysfunction in coronary resistance vessels in patients with angina pectoris and normal coronary angiograms. Am J Cardiol 199168996–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Egashira K, Inou T, Hirooka Y.et al Evidence of impaired endothelium‐dependent coronary vasodilation in patients with angina pectoris and normal coronary angiograms. N Engl J Med 19933281659–1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cannon R O, 3rd, Watson R M, Rosing D R.et al ngina caused by reduced vasodilator reserve of the small coronary arteries. J Am Coll Cardiol 198311359–1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chauhan A, Mullins P A, Taylor G.et al Effect of hyperventilation and mental stress on coronary blood flow in syndrome X. Br Heart J 199369516–524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bugiardini R, Pozzati A, Ottani F.et al Vasotonic angina: a spectrum of ischemic syndromes involving functional abnormalities of the epicardial and microvascular coronary circulation. J Am Coll Cardiol 199322417–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sax F L, Cannon R O, 3rd, Hanson C.et al mpaired forearm vasodilator reserve in patients with microvascular angina: evidence of a generalized disorder of vascular function? N Engl J Med 19873171366–1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tweddel A C, Martin W, Hutton I. Thallium scan in syndrome X. Br Heart J 19926848–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cannon RO I I I, Camici P G, Epstein S E. Pathophysiological dilemma of syndrome X. Circulation 199285883–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Camici P G, Marraccini P, Lorenzoni R.et al Coronary hemodynamics and myocardial metabolism in patients with syndrome X: response to pacing stress. J Am Coll Cardiol 1991171461–1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buchthal S D, den Hollander J A, Merz C N B.et al Abnormal myocardial phosphorus‐31 nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy in women with chest pain but normal coronary angiograms. N Engl J Med 2000342829–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buffon A, Rigattieri S, Santini S A.et al Myocardial ischemia‐reperfusion damage after pacing‐induced tachycardia in patients with cardiac syndrome X. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2000279H2627–H2633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nihoyannopoulos P, Kaski J C, Crake T.et al Absence of myocardial dysfunction during stress in patients with syndrome X. J Am Coll Cardiol 1991181463–1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maseri A, Crea F, Kaski J C.et al Mechanisms of angina pectoris in syndrome X. J Am Coll Cardiol 199117499–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galassi A R, Crea F, Araujo L I.et al Comparison of myocardial blood flow in Syndrome X and one‐vessel coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol 199372134–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bøtker H E, Moller N, Ovesen P.et al Insulin resistance in microvascular angina (syndrome X). Lancet 1993342136–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosano G M, Collins P, Kaski J C.et al Syndrome X in women is associated with oestrogen deficiency. Eur Heart J 199516610–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lanza G A, Sestito A, Cammarota G.et al Assessment of systemic inflammation and infective pathogen burden in patients with cardiac syndrome X. Am J Cardiol 20049440–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cosin‐Sales J, Pizzi C, Brown S.et al C‐reactive protein, clinical presentation, and ischemic activity in patients with chest pain and normal coronary angiograms. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003411468–1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cox I D, Botker H E, Bagger J P.et al Elevated endothelin concentrations are associated with reduced coronary vasomotor responses in patients with chest pain and normal coronary arteriograms. J Am Coll Cardiol 199934455–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lanza G A, Lüscher T F, Pasceri V.et al Effects of atrial pacing on arterial and coronary sinus endothelin‐1 levels in syndrome X. Am J Cardiol 1999841187–1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lanza G A, Giordano A G, Pristipino C.et al Abnormal cardiac adrenergic nerve function in patients with syndrome X detected by [123I]metaiodobenzylguanidine myocardial scintigraphy. Circulation 199796821–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Di Carli M F, Tobes M C, Mangner T.et al Effects of cardiac sympathetic innervation on coronary blood flow. N Engl J Med 19973361208–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gaspardone A, Ferri C, Crea F.et al Enhanced activity of sodium‐lithium countertransport in patients with cardiac syndrome X: a potential link between cardiac and metabolic syndrome X. J Am Coll Cardiol 1998322031–2034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shapiro L M, Crake T, Poole‐Wilson P A. Is altered cardiac sensation responsible for chest pain in patients with normal coronary arteries? Clinical observations during cardiac catheterization. BMJ 1988296170–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cannon R O, 3rd, Quyyumi A A, Schenke W H.et al bnormal cardiac sensitivity in patients with chest pain and normal coronary arteries. J Am Coll Cardiol 1990161359–1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Valeriani M, Sestito A, Le Pera D.et al Abnormal cortical pain processing in patients with cardiac syndrome X. Eur Heart J 200526975–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pasceri V, Lanza G A, Buffon A.et al Role of abnormal pain sensitivity and behavioral factors in determining chest pain in syndrome X. J Am Coll Cardiol 19983162–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosen S D, Paulesu E, Wise R J S.et al Central neural contribution to the perception of chest pain in cardiac syndrome X. Heart 200287513–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lanza G A. Abnormal cardiac nerve function in syndrome X. Herz 19992497–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaski J C, Rosano G M C, Collins P.et al Cardiac syndrome X: clinical characteristics and left ventricular function. Long‐term follow‐up study. J Am Coll Cardiol 199525807–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lanza G A, Manzoli A, Bia E.et al Acute effects of nitrates on exercise testing in patients with syndrome X: clinical and pathophysiological implications. Circulation 1994902695–2700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lanza G A, Sestito A, Iacovella S.et al Relation between platelet response to exercise and coronary angiographic findings in patients with effort angina. Circulation 20031071378–1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Halcox J P, Schenke W H, Zalos G.et al Prognostic value of coronary vascular endothelial dysfunction. Circulation 2002106653–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bugiardini R, Manfrini O, Pizzi C.et al Endothelial function predicts future development of coronary artery disease: a study of women with chest pain and normal coronary angiograms. Circulation 20041092518–2523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lanza G A, Andreotti F, Sestito A.et al Platelet aggregability in cardiac syndrome X. Eur Heart J 2001221924–1930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sestito A, Maccallini A, Sgueglia G A.et al Platelet reactivity in response to mental stress in syndrome X and in stable or unstable coronary artery disease. Thromb Res 200511625–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.