Abstract

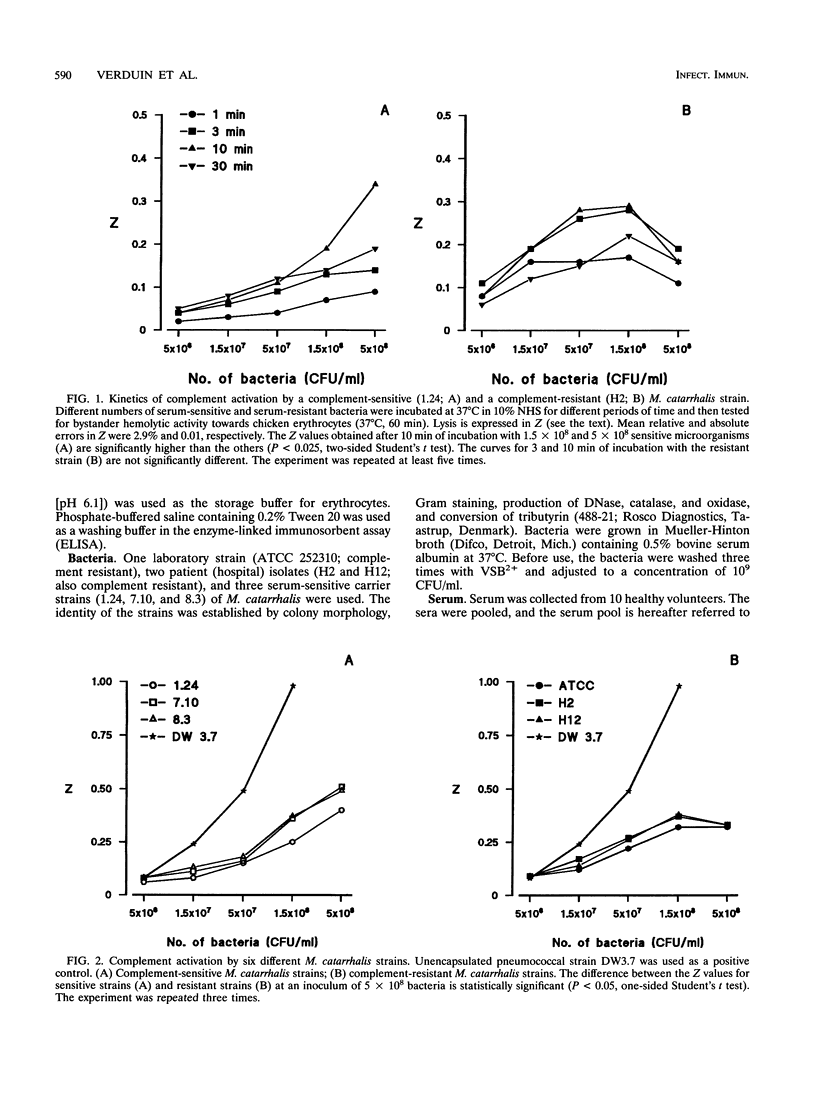

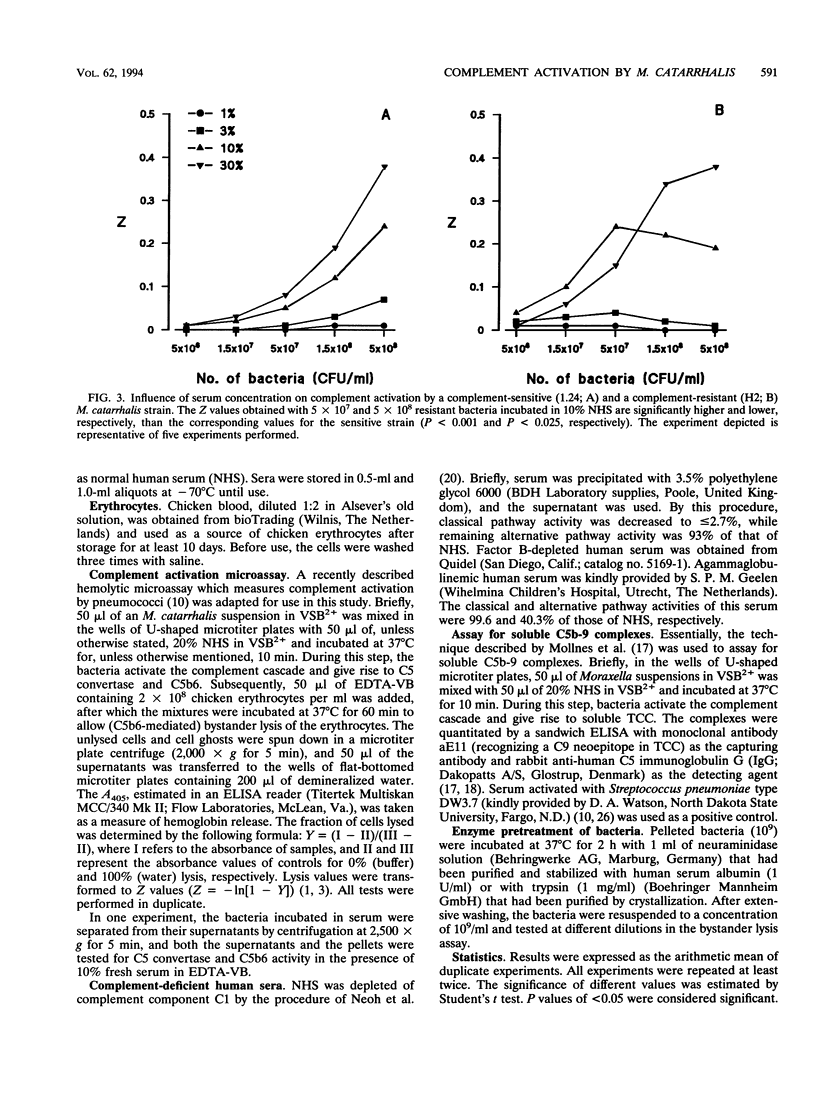

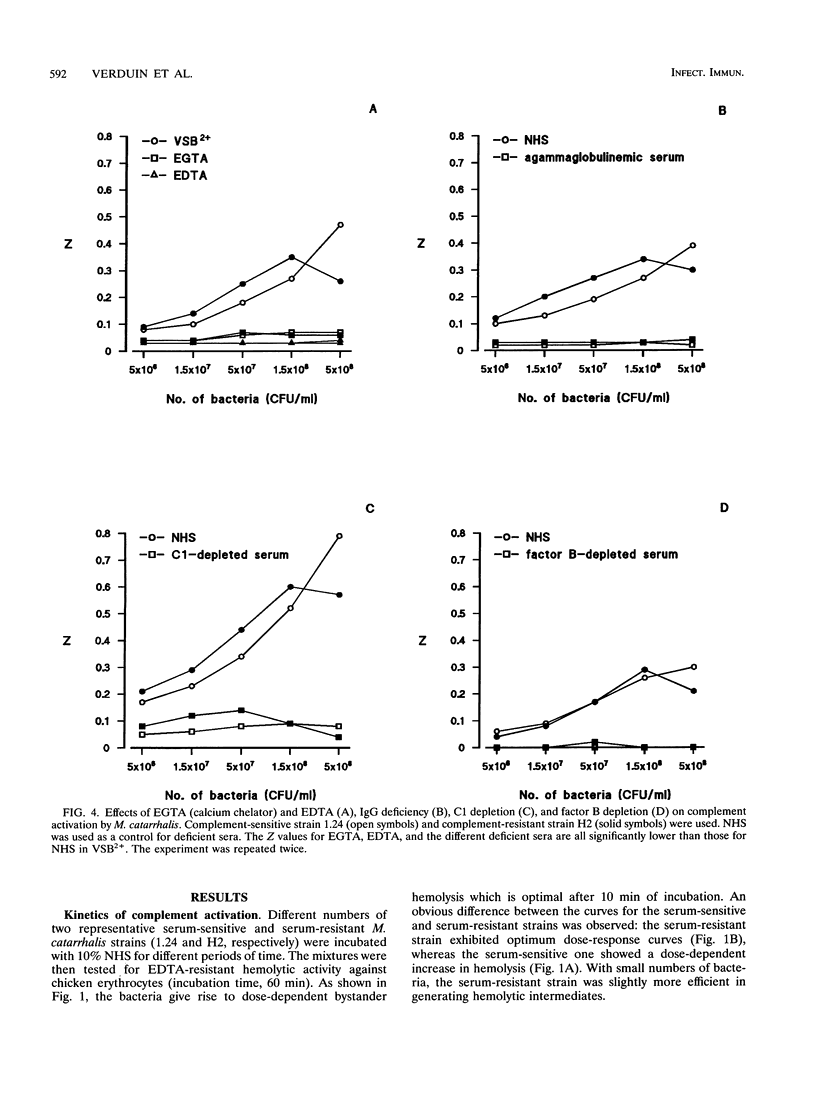

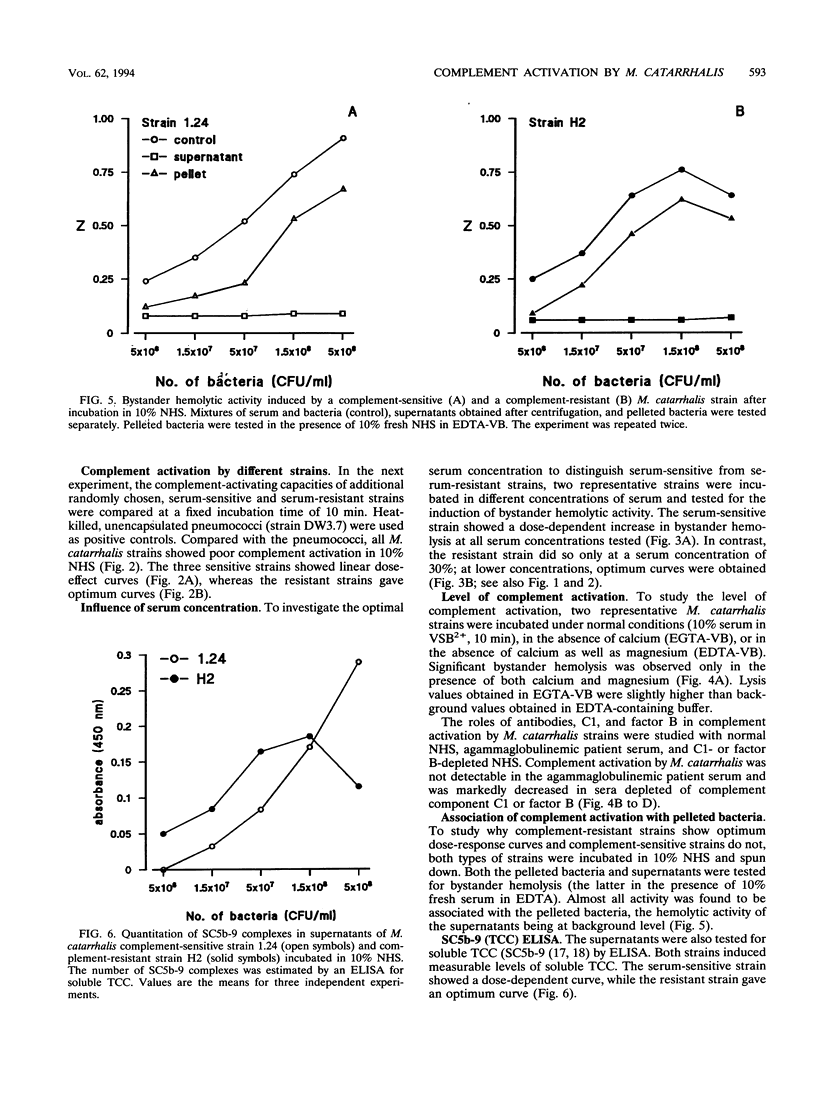

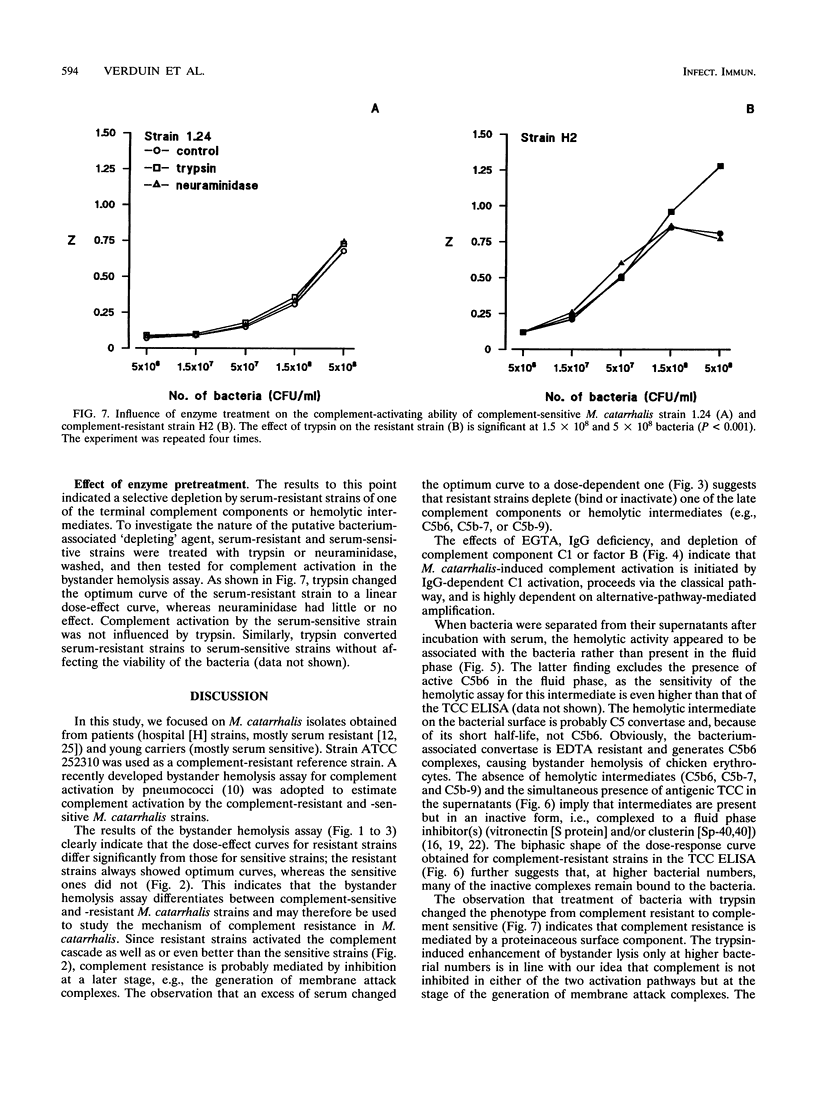

The mechanism of resistance to human complement-mediated killing in Moraxella catarrhalis was studied by comparing different complement-sensitive and complement-resistant M. catarrhalis strains in a functional bystander hemolysis assay and an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for soluble terminal complement complexes. Complement-resistant stains appeared to activate complement to the same extent as, or even slightly better than, complement-sensitive strains. This indicates that complement-resistant strains do not inhibit classical or alternative pathway activation but interfere with complement at the level of membrane attack complex formation. A clear difference in dose-response curves for resistant and sensitive strains was observed both in the bystander hemolysis assay and in the ELISA. Complement-resistant strains showed optimum curves, whereas complement-sensitive strains gave almost linear curves. We conclude that resistant strains bind and/or inactivate one of the terminal complement components or intermediates involved in membrane attack complex formation. Trypsin, known to abolish complement resistance, changed the optimum dose-response curve of a resistant strain to a linear one, which strongly suggests that complement resistance is mediated by an M. catarrhalis-associated protein. This protein acts directly or through the binding of a terminal complement inhibitor present in serum.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- BORSOS T., RAPP H. J. CHROMATOGRAPHIC SEPARATION OF THE FIRST COMPONENT OF COMPLEMENT AND ITS ASSAY ON A MOLECULAR BASIS. J Immunol. 1963 Dec;91:851–858. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle F. M., Georghiou P. R., Tilse M. H., McCormack J. G. Branhamella (Moraxella) catarrhalis: pathogenic significance in respiratory infections. Med J Aust. 1991 May 6;154(9):592–596. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1991.tb121219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle M. D., Gee A. P., Okada M., Borsos T. Differences in cell-bound C8 sites on chicken erythrocytes measured by their reactivity with guinea pig and human C9. J Immunol. 1980 Dec;125(6):2818–2822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandtzaeg P., Mollnes T. E., Kierulf P. Complement activation and endotoxin levels in systemic meningococcal disease. J Infect Dis. 1989 Jul;160(1):58–65. doi: 10.1093/infdis/160.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brorson J. E., Axelsson A., Holm S. E. Studies on Branhamella Catarrhalis (Neisseria catarrhalis) with special reference to maxillary sinusitis. Scand J Infect Dis. 1976;8(3):151–155. doi: 10.3109/inf.1976.8.issue-3.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catlin B. W. Branhamella catarrhalis: an organism gaining respect as a pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1990 Oct;3(4):293–320. doi: 10.1128/cmr.3.4.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman A. J., Jr, Musher D. M., Jonsson S., Clarridge J. E., Wallace R. J., Jr Development of bactericidal antibody during Branhamella catarrhalis infection. J Infect Dis. 1985 May;151(5):878–882. doi: 10.1093/infdis/151.5.878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Densen P. Complement deficiencies and meningococcal disease. Clin Exp Immunol. 1991 Oct;86 (Suppl 1):57–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1991.tb06209.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hager H., Verghese A., Alvarez S., Berk S. L. Branhamella catarrhalis respiratory infections. Rev Infect Dis. 1987 Nov-Dec;9(6):1140–1149. doi: 10.1093/clinids/9.6.1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hol C., Verduin C. M., van Dijke E., Verhoef J., van Dijk H. Complement resistance in Branhamella (Moraxella) catarrhalis. Lancet. 1993 May 15;341(8855):1281–1281. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)91185-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner K. A., Warren K. A., Hammer C., Frank M. M. Bactericidal but not nonbactericidal C5b-9 is associated with distinctive outer membrane proteins in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Immunol. 1985 Mar;134(3):1920–1925. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandrell R. E., Kim J. J., John C. M., Gibson B. W., Sugai J. V., Apicella M. A., Griffiss J. M., Yamasaki R. Endogenous sialylation of the lipooligosaccharides of Neisseria meningitidis. J Bacteriol. 1991 May;173(9):2823–2832. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.9.2823-2832.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milis L., Morris C. A., Sheehan M. C., Charlesworth J. A., Pussell B. A. Vitronectin-mediated inhibition of complement: evidence for different binding sites for C5b-7 and C9. Clin Exp Immunol. 1993 Apr;92(1):114–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1993.tb05956.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollnes T. E., Lea T., Frøland S. S., Harboe M. Quantification of the terminal complement complex in human plasma by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay based on monoclonal antibodies against a neoantigen of the complex. Scand J Immunol. 1985 Aug;22(2):197–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1985.tb01871.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollnes T. E., Lea T., Harboe M., Tschopp J. Monoclonal antibodies recognizing a neoantigen of poly(C9) detect the human terminal complement complex in tissue and plasma. Scand J Immunol. 1985 Aug;22(2):183–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1985.tb01870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy B. F., Kirszbaum L., Walker I. D., d'Apice A. J. SP-40,40, a newly identified normal human serum protein found in the SC5b-9 complex of complement and in the immune deposits in glomerulonephritis. J Clin Invest. 1988 Jun;81(6):1858–1864. doi: 10.1172/JCI113531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neoh S. H., Gordon T. P., Roberts-Thomson P. J. A simple one-step procedure for preparation of C1-deficient human serum. J Immunol Methods. 1984 Apr 27;69(2):277–280. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(84)90325-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons N. J., Curry A., Fox A. J., Jones D. M., Cole J. A., Smith H. The serum resistance of gonococci in the majority of urethral exudates is due to sialylated lipopolysaccharide seen as a surface coat. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992 Jan 15;69(3):295–299. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(92)90663-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preissner K. T. Structure and biological role of vitronectin. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1991;7:275–310. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.07.110191.001423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto-Hernandez J. L., Holtsclaw-Berk S., Harvill L. M., Berk S. L. Phenotypic characteristics of Branhamella catarrhalis strains. J Clin Microbiol. 1989 May;27(5):903–908. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.5.903-908.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verduin C. M., Hol C., Bootsma H. J., Verhoef J., van Dijk H. Observations on constitutional resistance to infection. Immunol Today. 1993 Jan;14(1):44–45. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90329-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D. A., Musher D. M. Interruption of capsule production in Streptococcus pneumonia serotype 3 by insertion of transposon Tn916. Infect Immun. 1990 Sep;58(9):3135–3138. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.9.3135-3138.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]