Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the long‐term clinical and exercise effect of chronic oral administration of the non‐selective endothelin receptor antagonist bosentan in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) related to congenital heart disease (CHD).

Design

Extension of a preceding prospective non‐randomised open clinical study on bosentan treatment in PAH related to CHD.

Setting

A tertiary referral centre for cardiology.

Patients

19 of the original 21 patients of mean (standard deviation (SD)) age 22 (3) years (13 with Eisenmenger syndrome) in World Health Organization (WHO) class II–IV and having a mean (SD) oxygen saturation of 87 (2) %.

Intervention

Patients received bosentan treatment for 2.4 (0.1) years and underwent clinical and exercise evaluation at baseline, 16 weeks and 2 years of treatment, with haemodynamic assessment at baseline and 16 weeks.

Results

All patients remained stable with sustained subjective clinical and WHO class improvement (p<0.01) at 16 weeks and 2 years of treatment without significant side effects or changes in oxygen saturation. After the initial 16‐week improvement (p<0.05) in peak oxygen consumption and exercise duration at treadmill test, and walking distance and Borg dyspnoea index at 6‐min walk test, all exercise parameters appeared to return to their baseline values at 2 years of follow‐up.

Conclusions

Long‐term bosentan treatment in patients with PAH related to CHD is safe and induces clinical stability and improvement, but the objective exercise values appear to slowly return to baseline. Larger studies on long‐term endothelin receptor antagonism including quality of life assessment are needed to evaluate the therapeutic role of bosentan in this population.

Congenital heart disease (CHD) associated with large aortopulmonary shunts and high pulmonary pressure induces pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) as a result of chronic exposure of the pulmonary vasculature to increased blood flow, pressure and shear stress leading to pulmonary vascular injury.1 Progressive increase in pulmonary vascular resistance is characterised by vascular wall remodelling with intimal fibrosis, increased medial thickness and plexiform lesions.2 Eisenmenger physiology with reversal of shunt causing cyanosis occurs when pulmonary vascular resistance exceeds the systemic vascular resistance,3 and is characterised by poor exercise tolerance and quality of life as well as high morbidity and mortality in a population of relatively young patients.4

Endothelin induces smooth muscle cell proliferation, vascular hypertrophy, inflammation and fibrosis as well as vasoconstriction through ETA and ETB receptors on smooth muscle cells and vasodilation through ETB receptors on the endothelium.5 It has been implicated in endothelial dysfunction and vascular remodelling,6 whereas increased endothelin levels have been correlated with the severity of PAH.7 Acute intravenous ETA receptor antagonism has been shown to improve haemodynamics in patients with PAH, including PAH related to CHD.8 Bosentan is the first oral non‐selective endothelin receptor antagonist shown to be effective in placebo‐controlled trials on adults with PAH,9,10 with sustained long‐term effects.11 Bosentan improved oxygenation and the functional status of adults with Eisenmenger syndrome in a small study without exercise or haemodynamic evaluation12; it also induced long‐term improvement in the functional and exercise status of adults with PAH due to CHD.13 Bosentan also improved the exercise capacity and haemodynamics over 16 weeks in the first placebo‐controlled trial on patients with Eisenmenger syndrome.14 We have previously reported clinical, exercise and haemodynamic improvement at 16 weeks of bosentan treatment in a population of paediatric and adult patients with PAH related to CHD.15

The purpose of this study, an extension of our above‐mentioned 16‐week trial to 2 years, was to assess the long‐term safety and tolerability as well as the clinical and exercise effect of oral bosentan treatment in patients with PAH related to CHD.

Patients and methods

Patient population

All patients had participated in the preceding open‐labelled non‐controlled trial involving 16 weeks of bosentan treatment; inclusion and exclusion criteria for the preceding study have been described previously.15 Briefly, all enrolled patients had severe PAH related to CHD with or without prior surgical repair with fixed elevated pulmonary vascular resistance that precluded further surgical intervention. Patients had no treatment regimen changes within the last month before enrolment and during the study period aside from the addition of bosentan treatment; none were taking epoprostenol, glibenclamide or ciclosporin to avoid drug interactions, or calcium channel blockers, as they were unresponsive to vasodilators.

Study protocol

This was an open‐label non‐controlled extension study approved by the institutional review committee and conducted according to institutional guidelines after obtaining written informed consent from the patients or their parent/guardian. Patients received oral bosentan regimen 125 mg twice daily if over 40 kg and 62.5 mg twice daily if between 20–40 kg after an initial 4‐week treatment period with half of the above dose, following previously published guidelines.16

All patients were evaluated before initiation, at 16 weeks and 2 years of treatment regarding history and subjected to clinical examination to define WHO functional class, unstructured interview including questions about perceived well‐being and exercise ability, maximal and submaximal exercise capacity; a complete haemodynamic study was performed at 0 and 16 weeks of treatment as part of the preceding study. Treatment safety was evaluated bimonthly by monitoring adverse events such as flushing and nasal congestion, laboratory tests such as liver function tests and haemoglobin concentration, electrocardiogram, vital signs, pulse oximetry recordings and discontinuations.

Maximal exercise capacity with recording of peak oxygen consumption, exercise duration and exercise capacity in metabolic equivalents was evaluated with the treadmill Dargie protocol as described previously.14 Submaximal exercise capacity was assessed by the 6‐min walk test16 with continuous pulse oximetry monitoring and recording of the Borg dyspnoea index17 experienced at completion of the test.

Statistical analysis

The descriptive data are presented as the mean (standard error of the mean), with median and range as appropriate. Changes from baseline are reported with 95% confidence interval. Significance of the differences from baseline to 16 weeks and 2 years was calculated using analysis of variances for repeated measures. Change in the WHO functional Class from baseline to 16 weeks and 2 years was analysed using the Wilcoxon's rank‐sum test. All p values were two‐tailed, with the required level of significance being p<0.05.

Results

Patients

Among the initial 21 patients with severe chronic PAH related to CHD reported previously, 2 patients expired presumably due to arrhythmic events.15 The remaining 19 patients, 10 (53%) males and 9 (47%) females, mean (standard deviation (SD)) 22 (3) years (range 6 to 43 years, median 19 years), were followed in this study. Table 1 describes the patients' demographic and baseline haemodynamic and exercise data.

Table 1 Demographic and baseline, haemodynamic and exercise data.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 22 (3) |

| Follow‐up period (years) | 2.4 (0.06) |

| Male:female | 10:9 |

| Diagnosis | |

| VSD with or without PDA | 6 |

| PDA | 1 |

| Aortopulmonary window | 3 |

| Complete atrioventricular canal, Down's syndrome | 1 |

| ASD | 1 |

| Double‐outlet right ventricle/VSD | 2 |

| Double‐inlet left ventricle/TGA | 2 |

| Congenitally corrected TGA/VSD | 1 |

| TGA/VSD after repair | 1 |

| VSD/PDA after repair | 1 |

| WHO class | |

| II | 5 |

| III | 12 |

| IV | 2 |

| Pulse oximetry (%) | 87 (2) |

| Mean pulmonary pressure (mm Hg) | 86 (3) |

| Pulmonary flow index (1/min/m2) | 4.1 (0.6) |

| Systemic flow index (1/min/m2) | 2.6 (0.2) |

| Pulmonary vascular resistance index (dyne·s/cm5·m2) | 1946 (290) |

| Systemic vascular resistance index (dyne·s/cm5·m2) | 2775 (156) |

| Peak oxygen consumption (ml/kg/min) | 17.3 (1.4) |

| 6‐min walking distance (m) | 417 (25) |

ASD, atrial septal defect; PDA, patent ductus arteriosus; TGA, transposition of the great arteries; VSD, ventricular septal defect; WHO, World Health Organization.

In this cohort, 16 patients had PAH associated with uncorrected unrestrictive communications at ventricular or great artery level without pulmonary stenosis, allowing complete mixing and equal pressures in the pulmonary and systemic circulation. Four of these patients had only left‐to‐right shunt at baseline, and the rest had baseline right‐to‐left shunt and cyanosis, as in Eisenmenger syndrome. The patient with atrial septal defect had unrestrictive atrial level shunt with fixed increased pulmonary vascular resistance associated with a ⩾35 mm defect. Two patients were born with unrestrictive ventricular and great artery level communications, which had been surgically repaired. Clinical evaluation and 6‐min walk test were performed on all patients, whereas treadmill exercise testing with oxygen consumption measurements was performed on all patients except the youngest, 6‐year‐old, patient and an adult patient with Downs syndrome.

Baseline characteristics

Most patients (74%) were significantly symptomatic (12 patients in WHO functional class III and 2 patients in class IV), except for five patients <12 years of age who were in WHO class II (table 1). Most patients (68%) were cyanotic with pulse oximetry <95% at rest in room air, whereas the four patients with unrestrictive mixing but absence of right to left shunt and the two completely repaired patients had normal baseline pulse oximetry. All patients had severe right ventricular dilation and hypertrophy on echocardiography with moderate to severe tricuspid regurgitation. Baseline maximal and submaximal exercise capacity as well as haemodynamic parameters (table 1) were considerably impaired, with median mean pulmonary artery pressure 84 mm Hg (range 55–100 mm Hg), median systemic blood flow index 2.5 1/min/m2 (range 1.6–3.8 1/min/m2) and median pulmonary vascular resistance index 1871 dyne·s/cm5·m2 (range 508–4387 dyne·s/cm5·m2).

Treatment effect

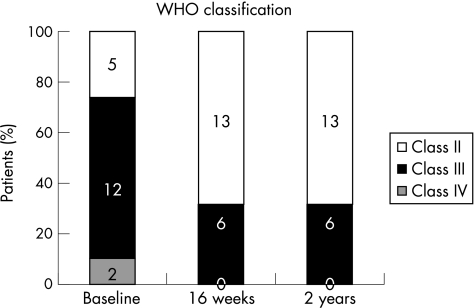

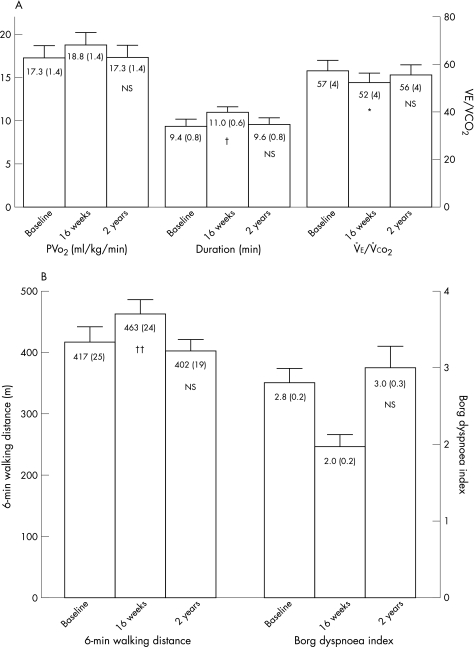

All 19 patients remained stable on oral bosentan treatment over a follow‐up period of 2.4 (0.1) years (1.7–2.6 years). All patients were active at work and school without hospitalisations, reporting “feeling considerably improved” and “performing better” especially during exercise. Figures 1 and 2 depict the changes from baseline observed after 16 weeks and 2 years of bosentan treatment in the WHO classification, and the maximal and submaximal exercise tolerance.

Figure 1 Change in World Health Organization functional class from baseline to 16 weeks and 2 years of bosentan treatment (higher classes indicate greater severity of disease). Numbers inside bars indicate the number of patients in each class.

Figure 2 Change in maximal (A) and submaximal (B) exercise parameters from baseline to 16 weeks and 2 years of bosentan treatment. Numbers inside bars denote mean (standard error of the mean); mets, metabolic equivalents; PVO2, peak oxygen consumption; * p<0.05 v baseline; † p<0.01 v baseline; †† p<0.0001 v baseline.

At week 16, 10 patients had WHO functional class improved by one (the two class IV patients improved to class III and eight class III patients improved to class II), whereas the four class III patients and the five class II patients remained stable (fig 1). This improvement in WHO classification was sustained without changes over the 2 years' follow‐up period (fig 1).

Exercise evaluation at 16 weeks with Dargie treadmill protocol showed, compared with baseline, a mild but significant increase in peak oxygen consumption by 1.5 (95% CI 0.002 to 3) ml/kg/min, exercise capacity by 0.4 (95% CI –0.005 to 0.8) metabolic equivalents and duration by 1.6 (95% CI 0.5 to 2.7) min, with all parameters returning to their baseline values at 2 years' follow‐up (fig 2). The ventilatory equivalent for carbon dioxide (VE/VCO2) at anaerobic threshold at 16 weeks also decreased significantly (p<0.05) from 57 (4) to 52 (4) (95% CI 0.9 to 9.1), also returning to baseline values at 2 years' follow‐up. During the 6‐min walk test, patients at 16 weeks showed an increase in walk distance by 46 (95% CI 18 to 73) m and a reduction in Borg dyspnoea index by 0.8 (95% CI 0.3 to 1.4), again reaching baseline values at 2 years' follow‐up (fig 2).

Safety and tolerability

Flushing and dizziness were reported once each, but resolved within 2 weeks without regimen changes. Liver function tests increased to twice the upper limit of normal in two patients, but returned to normal within 2 months without regimen changes. Interference with the international normalised ratio, other adverse events or discontinuations were not observed in this study. Pulse oximetry in room air and haemoglobin concentration did not change significantly in this cohort, regardless of the presence or not of cyanosis at baseline, and no patient required phlebotomy or red cell depletion during the study.

One patient reported disappearance of her bimonthly mild haemoptysis episodes, whereas another was hospitalised once with her first moderate haemoptysis episode, which resolved conservatively and did nor recur during the study period. One patient exhibited non‐sustained ventricular tachycardia in surveillance Holter monitor and was started on oral amiodarone therapy.

Discussion

This study is an extension of our previous open‐label trial investigating the long‐term safety and effect of bosentan in patients with PAH related to CHD. In the preceding study, 16 weeks' treatment with bosentan induced improved haemodynamics including decrease in pulmonary pressures and resistance in this population, as well as functional class and maximal and submaximal exercise tolerance.15 In the present open‐label extension study, long‐term oral treatment with bosentan for over 2 years in patients with PAH related to CHD proved to be safe and induced clinical stability and consistent improvement in WHO classification. After the initial improvement at 16 weeks of treatment in maximal and submaximal exercise, however, all exercise parameters at 2 years seem to be slowly returning to baseline.

Aside from the two probably arrhythmic deaths during the initial 16‐week study15 in WHO class IV patients despite their clinical improvement, bosentan administration for 2–3 years was well tolerated in this cohort of patients with PAH related to CHD without increased cyanosis, serious side effects or discontinuations. These results are in agreement with previous clinical studies with bosentan in PAH in the adult11 and paediatric population.17 PAH related to CHD is a progressive and fatal disease, and clinical improvement and stability appear very encouraging in this population, given the unattractive options of continuous intravenous epoprostenol or lung transplantation that these patients have to face on clinical worsening. These results become more exciting in view of the growing evidence for cardiac remodelling and improved right ventricular function observed with bosentan in PAH both by echocardiographic indices18 and by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy.19 Clinical stability and delay of deterioration for over 2 years in these patients may present an important gain in their management towards combination treatments with endothelin antagonism, phosphodiesterase‐5 inhibition and inhaled prostacyclin analogues, as supported by recent reports.20

The slow return of objective exercise parameters to baseline despite sustained clinical improvement after 2–3 years of bosentan treatment is certainly disconcerting and different from previous observations with 6–22 months' follow‐up in idiopathic PAH21 and 2 years' follow‐up in PAH due to CHD.13 This discrepancy between our study and the other CHD PAH report13 may be due to the higher cardiac output with lower pulmonary vascular resistance of their population, despite their older age, possibly indicating less advanced disease stage. Also, that report had a more variable follow‐up of 1– 3 years and included a considerable number of postoperative patients and patients with atrial septal defects, both possibly resembling idiopathic PAH in behaviour. The mechanism of improvement with bosentan in PAH due to CHD remains unclear, as the only placebo‐controlled trial over 16 weeks showed exercise improvement without increase in pulmonary blood flow.14

Clinical deterioration after long‐term treatment with bosentan has been reported before in idiopathic PAH, leading to combination therapy.22 Decline of exercise data in our study may be due to tachyphylaxis, which should probably have become apparent within the initial 16‐week trial period, or due to natural progression of the disease, which, although relatively slow in this population, can be accelerated in WHO class III patients. This decline certainly indicates the need for large placebo‐controlled studies with extended follow‐up in order to assess the long‐term effect of endothelin antagonism in PAH related to CHD and delineate the organisation and timing of escalation of treatment. This study examines, unlike most others, strictly patients with PAH related to CHD with the longest follow‐up period yet and adds, we think, important information in this exciting field of clinical research.

It is unclear whether exercise deterioration after 2 years on bosentan would merely precede clinical worsening in this study, as these patients have usually adapted their lifestyle to decreased need for exercise, especially maximal. The discrepancy between clinical and exercise behaviour of this patient cohort stresses the importance of quality of life assessment as a major outcome measure in clinical PAH studies, as has been advocated before.23 Patients with PAH have functional limitations with moderate to severe impairment in multiple domains of health‐related quality of life,24 whereas haemodynamic measurements do not always correlate with quality of life scores.25 Evaluation of quality of life as an outcome marker becomes increasingly important in this population, especially now that appropriate questionnaires for PAH are being developed.26

The limitations of this study, including the lack of a placebo group, the absence of objective quality of life assessment, the relatively small sample size, and the patients' heterogeneity in age and diagnosis, may render its interpretation problematic. Against these limitations, this study reports the clinical and exercise effects of bosentan in the infrequently studied population of PAH related to CHD, including mainly patients with the Eisenmenger syndrome, and, moreover, shows possible decline of the observed effect on exercise parameters with time. Obviously, further long‐term placebo‐controlled studies are warranted to evaluate fully the effect and survival benefit of endothelin antagonism in PAH related to CHD and guide further management of this population.

In conclusion, this study shows that long‐term oral administration of the non‐selective endothelin antagonist bosentan for over 2 years induces sustained clinical improvement in patients with chronic PAH related to CHD, including Eisenmenger syndrome, whereas the objective maximal and submaximal exercise parameters appear to slowly return to baseline. Additional, larger and longer studies with endothelin antagonism in PAH related to CHD are needed to assess the safety and duration of the effect and influence of combination treatments and escalation of treatment in this patient population.

Abbreviations

CHD - congenital heart disease

PAH - pulmonary arterial hypertension

WHO - World Health Organization

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

This study was conducted with the approval of the Onassis Cardiac Surgery Centre Ethics Committee and after obtaining informed consent from the patients or their parent/guardian.

References

- 1.Vongpatanasin W, Brickner M E, Hillis L D.et al The Eisenmenger syndrome in adults. Ann Intern Med 1998128745–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farber H W, Loscalzo J. Pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med 20043511655–1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wood P. The Eisenmenger syndrome or pulmonary hypertension with reversed central shunt. BMJ 195846755–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Daliento L, Somerville J, Presbitero P.et al Eisenmenger syndrome. Factors relating to deterioration and death. Eur Heart J 1998191845–1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clozel M. Effects of bosentan on cellular processes involved in pulmonary arterial hypertension: do they explain the long‐term benefit? Ann Med 200335605–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wort S J, Woods M, Warner T D.et al Endogenously released endothelin‐1 from human pulmonary artery smooth muscle promotes cellular proliferation: relevance to pathogenesis of pulmonary hypertension and vascular remodeling. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 200125104–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allen S W, Chatfield B A, Koppenhafer S A.et al Circulating immunoreactive endothelin‐1 in children with pulmonary hypertension. Association with acute hypoxic pulmonary vasoreactivity. Am Rev Respir Dis 1993148519–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Apostolopoulou S C, Rammos S, Kyriakides Z S.et al Acute endothelin A receptor antagonism improves pulmonary and systemic haemodynamics in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension that is primary or autoimmune and related to congenital heart disease. Heart 2003891221–1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Channick R N, Simonneau G, Sitbon O.et al Effects of the dual endothelin‐receptor antagonist bosentan in patients with pulmonary hypertension: a randomised placebo‐controlled study. Lancet 20013581119–1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rubin L J, Badesch D B, Barst R J.et al Bosentan therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med 2002346896–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sitbon O, Badesch D B, Channick R N.et al Effects of the dual endothelin receptor antagonist bosentan in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension: a 1‐year follow‐up study. Chest 2003124247–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Christensen D D, McConnell M E, Book W M.et al Initial experience with bosentan therapy in patients with the Eisenmenger syndrome. Am J Cardiol 200494261–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schulze‐Neick I, Gilbert N, Ewert R.et al Adult patients with congenital heart disease and pulmonary arterial hypertension: first open prospective multicenter study of bosentan therapy. Am Heart J 2005150716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galie N, Beghetti M, Gatzoulis M A.et al Bosentan therapy in patients with Eisenmenger syndrome: a multicenter, double‐blind, randomized, placebo‐controlled study. Circulation 200611448–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Apostolopoulou S C, Manginas A, Cokkinos D V.et al Effect of the oral endothelin antagonist bosentan on the clinical, exercise, and haemodynamic status of patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension related to congenital heart disease. Heart 2005911447–1452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barst R J, Ivy D, Dingemanse J.et al Pharmacokinetics, safety, and efficacy of bosentan in pediatric patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Clin Pharmacol Ther 200373372–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenzweig E B, Ivy D D, Widlitz A.et al Effects of long‐term bosentan in children with pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 200546697–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Galie N, Hinderliter A L, Torbicki A.et al Effects of the oral endothelin‐receptor antagonist bosentan on echocardiographic and Doppler measures in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003411380–1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spindler M, Schmidt M, Geier O.et al Functional and metabolic recovery of the right ventricle during bosentan therapy in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 20057853–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoeper M M, Markevych I, Spiekerkoetter E.et al Goal‐oriented treatment and combination therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J 200526858–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seyfarth H J, Pankau H, Hammerschmidt S.et al Bosentan improves exercise tolerance and Tei index in patients with pulmonary hypertension and prostanoid therapy. Chest 2005128709–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoeper M M, Faulenbach C, Golpon H.et al Combination therapy with bosentan and sildenafil in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J 2004241007–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peacock A, Naeije R, Galie N.et al End points in pulmonary arterial hypertension: the way forward. Eur Respir J 200423947–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shafazand S, Goldstein M K, Doyle R L.et al Health‐related quality of life in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Chest 20041261452–1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taichman D B, Shin J, Hud L.et al Health‐related quality of life in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Respir Res 2005692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McKenna S P, Doughty N, Meads D M.et al The Cambridge Pulmonary Hypertension Outcome Review (CAMPHOR): a measure of health‐related quality of life and quality of life for patients with pulmonary hypertension. Qual Life Res 200615103–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]