Abstract

An extensive conformational study of the analgesic dipeptide kyotorphin (L-Tyr-L-Arg) at different pH values was performed using a constant-pH molecular dynamics method. This dipeptide showed a remarkable pH-dependent conformational variety. The protonation of the N-terminal amine was identified as a key element in the transition between the more extended and the more packed conformational states, as monitored by the dihedral angle defined by the atoms 1Cβ-1Cα-2Cα-2Cβ. The principal-component analysis of kyotorphin identified two major conformational populations (the extended trans and the packed cis) together with conformations that occur exclusively at extreme pH values. Other, less stable conformations were also identified, which help us to understand the transitions between the predominant populations. The fitting of kyotorphin's conformational space to the structure of morphine resulted in a set of conformers that were able to fulfill most of the constraints for the μ-receptor. These results suggest that there may be strong similarities between the kyotorphin receptor and the structural family of opioid receptors.

INTRODUCTION

The structure, function, and dynamics of most biomolecules in solution are very dependent on pH (1). pH effects occur via electrostatic interactions, one of the strongest forces at the molecular level, and can have a direct influence on molecular structure. However, a small peptide does not exhibit a preferred structure in aqueous solution, but rather an ensemble of interconverting conformations (2). In this case, pH has a more subtle effect by changing the distribution of the conformer populations (3).

Until recently, computational studies dealt with pH using mostly two simplified approaches. The first consists of setting the solute (e.g., protein) protonable groups to the states they would have in a solution at the intended pH and then performing molecular mechanics/dynamics (MM/MD) simulations. This means that any desolvation and site-site interaction effects caused by the solute environment upon protonation are entirely neglected. The second way consists of using a rigid solute structure and simplified electrostatic-oriented models, such as Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) (4–12), generalized Born (13–15), or protein dipoles and Langevin dipoles (16,17). (Several other approaches are discussed in the literature as well (18–24).) The protonation free energies thus obtained can then be used for sampling protonation states by Monte Carlo (MC) (7,25–27) or other approximate methods (7,16,28–31), making possible the calculation of pKa values. This approach explicitly considers the effect of desolvation and site-site interactions, but the use of a single solute conformation makes it impossible to account for structural reorganization and protonation-conformation coupling in general (32–35). These problems can be attenuated by the use of linear response approximations that combine MD with simplified approaches (16,17,32,36). Another, more general route is to use recently developed methods for constant-pH MD (37–50), some of which explore the complementarity between standard MD and simplified methods (see Machuqueiro and Baptista (50) for a more detailed comparison). One of these constant-pH MD methods, called stochastic titration (39), assumes that the dynamics of a solute with a fixed protonation state can be obtained from MM/MD, as usual, and that its electrostatics at fixed conformation can be captured by a PB model (followed by MC sampling of protonation states). Stochastic titration could successfully predict pKas for succinic acid (a ΔpKa of 1.75 for an experimental value of 1.45) (39) and decalysine (pKa of 10.2 for both simulation and experiment) (50), showing that the method can properly model the coupling between protonation and conformation in small and relatively large molecules.

Kyotorphin (KTP) was first isolated from bovine brain by Takagi and co-workers (51,52). The name was assigned to reflect an endorphin-like substance and the fact that it was discovered in Kyoto, Japan. This endogenous dipeptide (L-Tyr-L-Arg) belongs to the neuropeptide family (53–58) due to its opiate-like activity. KTP is distributed unevenly in regions of rat brain (52) and may be formed both by processing precursor proteins and by the biosynthesis from Tyr and Arg (57). The Tyr-Arg motif exists widely throughout the brain, not only as KTP, but also as the N-terminal part of several endogenous analgesic peptides (59,60). Also, this peptide is very rapidly degraded by aminopeptidases (61). Many of these properties are typical of neurotransmitters and it is not surprising that KTP has also nonopioid actions independent of enkephalin release (62). There is evidence suggesting that KTP does not bind the opiate receptors (μ, δ, κ) but that instead it exerts a Met-enkephalin-releasing force (53). These results led to the suggestion that the dipeptide binds to a specific receptor (KTP receptor, KTPr) (56), triggering a cascade of events that leads to strong analgesia in the brain (57,63). Two mechanisms of action have been proposed: 1), direct activation of the KTPr, inducing Met-enkephalin release (which can activate the δ-receptor), followed by Gαi and phospholipase C activations (64,65); 2), a fast degradation of KTP, resulting in L-Arg, which is a potent substrate for nitric oxide synthase, with the NO thus formed inducing the release of Met-enkephalin (66). Despite the fact that several studies (45,53,54) confirm the existence of a KTPr, it has not yet been identified. There is still the question of whether the KTPr is specific (45) or the result of a mixed oligomerization of μ- and δ-opioid receptors (67). Recent results suggest that KTP can also release opioid peptides from rat cardiac muscle and have an indirect regulatory role in β-adrenergic action through cross-talk with opioid receptors (68).

The molecular interaction between KTP and its receptor remains unknown. In fact, not much is known besides the fact that the receptor seems to be functionally coupled to Gαi and that it is strongly antagonized by the dipeptide L-Leu-L-Arg (64). There are obvious similarities between KTP and most of the endogenous opioid peptides and even with morphine. The L-Tyr residue at the first position of the peptide is present in most of the opioid peptides and is believed to be crucial for receptor recognition (69,70) due to both π-stacking (71) and hydrogen-bonding with the alcohol of the phenol group (72). A protonable N-terminal group is also present in KTP and, when protonated, can form a salt bridge with an anionic group in the receptor, which is typical for the morphine/μ-receptor interaction (72). Also, when KTP's N-terminal group is protonated, the molecule becomes positively charged, which is an important characteristic present in both dynorphin A and nociceptin/orphanine FQ. These cationic peptides bind to two receptors that exhibit a highly acidic second exofacial loop (κ-receptor for dynorphin A and ORL1 receptor for nociceptin/orphanine FQ) (69,70). On the other hand, there is an important difference between KTP and the opioid peptides. The introduction of two methyl groups (orto position) in the phenol ring of the Tyr residue in KTP (H-Dmt-Arg-OH) is detrimental to the interaction with the KTPr (62), unlike in the case of opioid peptides, where replacement of Tyr with Dmt produces a very significant potency enhancement (73). Thus, the binding site of KTPr interacting with the Tyr residue of KTP has structural requirements that differ from those of the binding sites of opioid receptors interacting with the Tyr residue of opioid peptides (62).

Recently, the structural constraints needed for KTP-receptor interactions were addressed with a combination of experimental and theoretical approaches (74). The study showed that pH has a strong influence on the conformational behavior of KTP and an acylated KTP derivative, both in water and in model systems of membranes. In fact, the conformational space of KTP is expected to depend strongly on pH, due to its four titrable sites. Around physiological pH, the N-terminus protonation state should have a strong effect on both the conformation and total charge of the molecule.

The aim of this work is threefold. First, this work intends to study KTP using the stochastic titration method for constant-pH MD (39,50), which is theoretically more rigorous than the linear response approximation (LRA) method used previously (74); analogously to stochastic titration, that LRA method combines PB/MC and MM/MD, but it introduces further assumptions (32). The second aim of this work is to carry out a more extensive conformational analysis of the system than the one presented by Lopes and co-workers (74). Third, this work also intends to further test the performance of the stochastic titration method, which has so far only been applied to succinic acid (39) and decalysine (50). Overall, our general objective is to elucidate KTP's preferred conformations at different pH values and how they correlate with known structural constraints needed for opioid ligand-receptor interactions.

COMPUTATIONAL DETAILS AND METHODS

Constant-pH MD method

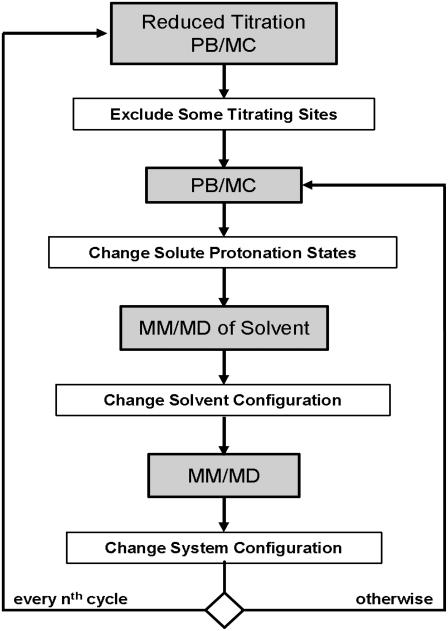

The constant-pH MD method implemented is the stochastic titration method previously proposed (39). The current implementation is described in a recent publication (50), which should be consulted for further details. The method relies on different sequential blocks (Fig. 1). The first block is a PB/MC calculation. The protonation states resulting from the last MC step are assigned to the protein. The second block is the solvent-relaxation dynamics, a short MM/MD simulation of the system with frozen protein, which allows the solvent to adapt to the new protonation states (the duration of this block is hereafter designated as τrlx). The last block is a full MM/MD simulation of the unconstrained system (the duration of this block is hereafter designated as τprt). A variant of the reduced titration method is used (31,50), in which we run a full PB/MC calculation on the system every 10th step to assign a fixed state to all the sites whose mean occupancies fall outside a predefined threshold (0.001). This approach is very useful, because, when simulating pH values too far away from certain site pKas, these become temporarily excluded from the calculations, hence strongly decreasing the computational cost.

FIGURE 1.

Schematic representation of the algorithm used.

For the PB and MC calculations we used the programs MEAD (75) and MCRP (27), respectively. The atomic charges and radii used in the PB calculations were derived from the GROMOS 43A1 force field (76,77). All PB calculations consisted of finite-difference linear Poisson-Boltzmann calculations performed with the program MEAD (version 2.2.0) (75) at a temperature of 300 K, a molecular surface defined with a solvent probe radius of 1.4 Å, and a Stern (ion-exclusion) layer of 2.0 Å. The dielectric constants were 2 for KTP and 80 for the solvent. A two-step focusing procedure (78) was used, with consecutive grid spacings of 1.0 and 0.25 Å. The MC runs were performed using 105 MC cycles, one cycle consisting of sequential state changes over all individual sites and also all pairs of sites with at least one interaction term above 2.0 pKa units (27). In all cases, the computed average protonations had errors lower than 0.0001; for each site, this error is computed as the correlation-corrected standard deviation of the average, taking as correlation time the value at which the autocorrelation of the protonations goes below 0.1.

MM/MD settings

All simulations were performed with the GROMOS 43a1 force field (76,77) for the GROMACS 3.2.1 distribution (79,80) (with some modifications (50)) and with the SPC water model (81). Periodic boundary conditions were used with a rhombic dodecahedral unit cell. A twin-range cutoff was used, with short- and long-range cutoffs of 8 Å and 14 Å, respectively, and with neighbor lists updated every five steps. Long-range electrostatics interactions were treated using the generalized-reaction-field method (82). The ionic strength in the simulations was set as an external parameter using a modified version of the GROMACS 3.2.1 distribution (50). All bond lengths were constrained using the LINCS algorithm, and a time step of 2 fs was used. Two Berendsen's temperature couplings to baths at 300 K, and with a relaxation time of 0.1 ps (83), were used for both the solute and solvent. A Berendsen's pressure coupling (83) was used with a relaxation time of 0.5 ps and a compressibility of 4.5 × 10−5 bar−1.

The dipeptide was built in an extended conformation, placed in the center of the box and filled with 1199 water molecules. The system was minimized first with ∼40 steps of steepest descent followed by ∼700 steps using the low-memory Broyden-Fletcher-Goldfarb-Shanno algorithm. The initiation was achieved by harmonically restraining all atoms in a 50-ps MD simulation, followed by another 50 ps simulation with only the CA atoms restrained. Note that this initiation was done for two different startup systems, one with the N-terminus deprotonated and the other with the N-terminus protonated (Tyr and Arg side chains were protonated and the C-terminus was deprotonated). The charged N-terminus conformation was used as the starting structure for the simulations at pH 2–7, whereas simulations at pH 8–12 started with the neutral N-terminus conformation.

Runs of 100 ns were performed and the first 5 ns were discarded to get the system equilibrated. The relaxation of the solvent (τrlx) and the full system dynamics segment (τprt) were done for 1.0 ps each. If τprt is too short, there will be an increase of computational cost, and if it is too long, we will have a slower conformational sampling. In this work, the τrlx and τprt values were optimized to get high conformational sampling and good system stability at the expense of a high computational cost (we “waste” 50% of our MM/MD time).

The main simulations were performed at ionic strength of 0.1 M. Two extra sets of simulations of 30 ns were performed at ionic strengths 0.0 and 1.0 M and at pH values 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 11.

General analysis

All structural analyses were done using GROMACS (79,80) or in-house tools. Errors were computed using standard methods (84).

Principal-component analysis

Principal-component analysis (PCA) is a method that can be used to simplify a dataset (85). It is a linear transformation that changes a set of (possibly) correlated variables into a set of uncorrelated variables called principal components (PCs). The first PC (i.e., the PC with the largest eigenvalue) accounts for as much of the variability in the data as possible, and each succeeding PC (in order of decreasing eigenvalues) accounts for as much of the remaining variability as possible, while being uncorrelated with the previous ones. The strongest correlations in the dataset tend to be captured by the first PCs. PCA can be used for reducing dimensionality by retaining only a few of the first PCs, hopefully without much loss of information. PCA is algebraically equivalent to the diagonalization of the covariance matrix: each PC is the variable associated with an eigenvector, and its variance is given by the corresponding eigenvalue.

In our analysis, we fitted separately all our trajectories at different pH values to a fixed KTP structure; changing this structure had no major effect on the results (data not shown). The atoms subsequently used to calculate the covariance matrix were CA, CB, CG, and C from Tyr, and N, CA, CB, CG, and NE from Arg. The trajectories were projected on the first three principal components, which account for ∼75% of the information available. The set of all points (conformations) thus projected was used to obtain a kernel estimate of the corresponding probability density (86), which was computed on a grid of (0.1 Å)3 bins, using a Gaussian kernel and a bandwidth of 0.2 Å. This probability density is the projection of the original isothermal-isobaric distribution onto the subspace spanned by the first three PCs, and is expected to retain the major features of the original distribution. The most populated peaks of the density (usually the higher ones) were then selected using an energy cutoff of 2RT, where the energy was computed according to

|

where x is the coordinate in the 3D space of the first PCs and P(x) is the probability density at point x. A representative conformation was chosen for each peak, namely the one closest to the peak top.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Titration with constant-pH MD

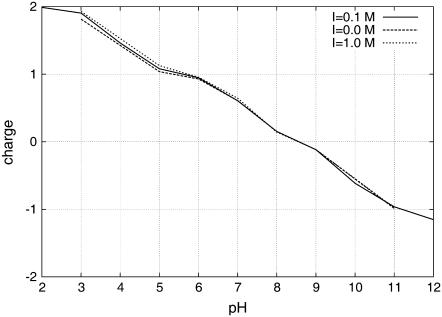

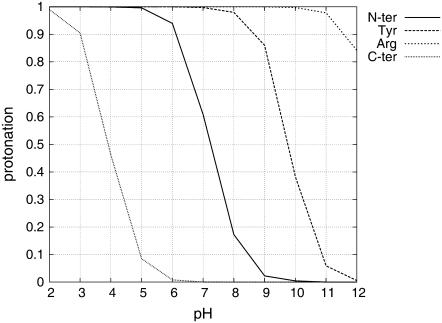

The titration of KTP (Figs. 2 and 3) was computed by averaging at each pH value the occupancy states of all four titrable sites over 95 ns for the simulations at ionic strength 0.1 M, and over 25 ns for the simulations at ionic strengths 0.0 and 1.0 M.

FIGURE 2.

Titration curves of KTP at different values of ionic strength.

FIGURE 3.

Titration curves of KTP titrable sites at 0.1 M.

From the titration curves, we observe that the ionic-strength effect is very weak (Fig. 2). These results are not surprising because ionic strength works by shielding the interactions between close charged groups, and KTP is a small molecule without a unique conformation in water. According to these results, KTP is only mildly positively charged at physiological pH, reaching the isoelectric point around pH 8.5. When looking at each site specifically (Fig. 3), we obtain pKa values for the three relevant titrable sites (Arg guanidinium is titrating very far away from physiologic conditions) (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

pKa values obtained from the titration curves at I = 0.1 M

| Titration site | pKa values |

|---|---|

| N-ter | 7.14 ± 0.14 |

| Tyr | 9.94 ± 0.26 |

| Arg | >12 |

| C-ter | 4.04 ± 0.15 |

pKa values were computed using a third-order polynomial interpolation.

It is interesting to compare the N-terminus titration observed here with the theoretical and experimental ones in Lopes et al. (74). The pKa of 7.14 computed here with constant-pH MD is higher than the 6.2 value previously computed with the LRA method (74). Given that both methods rely on the same PB/MC and MM/MD approaches (but combined differently), this discrepancy may be due to sampling problems in either method or to failure of the linear response assumption. In particular, we show below (see “Detailed conformational analysis with PCA”) that some conformational classes show sudden changes upon N-terminus titration, which could result in poor distribution overlap and consequent breakdown of the linear response assumption (see Eberini et al. (32) for details). On the other hand, 6.2 is also the pKa value estimated from the ion exchange experiment (74) (we note that Fig. 6 a in Lopes et al. (74) shows the release of positively-charged KTP from an anionic resin, thus corresponding only to the N-terminus group. This value seems too low for such an exposed group and actually makes problematic the interaction with the negatively charged membrane (74). In any case, this issue could probably be clarified by further experimental studies.

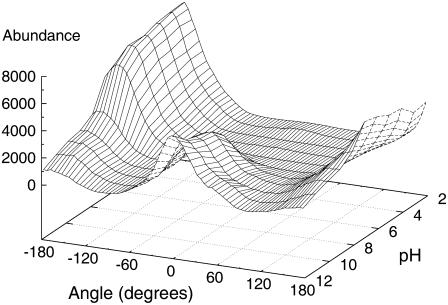

FIGURE 6.

Histogram surface of the dihedral angle CB-CA-CA-CB for KTP at ionic concentration of 0.1 M at different pH values. Ninety-five thousand conformations are used for each pH value. Similar data is observed for 0.0 and 1.0 M ionic strength (data not shown).

Conformational mapping with constant-pH MD

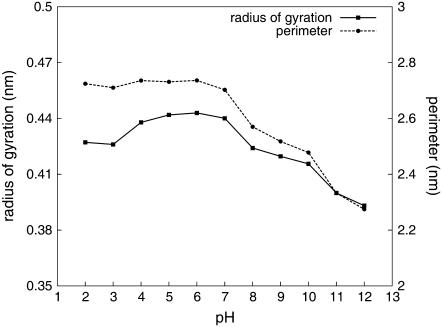

As anticipated, our simulations clearly show that KTP does not have a unique structure in solution. In fact, this dipeptide showed a remarkable conformational freedom, especially at low pH values. We started by measuring the molecule packing at different pH values. This was done by computing the radius of gyration and the perimeter of the triangle formed by the following atoms: N from the N-terminus; O from Tyr hydroxyl; and C from Arg guanidinium. Both the radius of gyration and the perimeter are expected to be higher when the molecule is in an extended conformation and lower when the molecule is more packed. As seen in Fig. 4, there is a clear gain of packing with pH increase. Also, the radius of gyration indicates a slight structural packing at lower pH values, suggesting that some structure other than the extended one is being preferred.

FIGURE 4.

Average radius of gyration and average perimeter (triangle formed between N-terminus, OH (Tyr), and CZ (Arg)) over pH, at 0.1 M ionic strength.

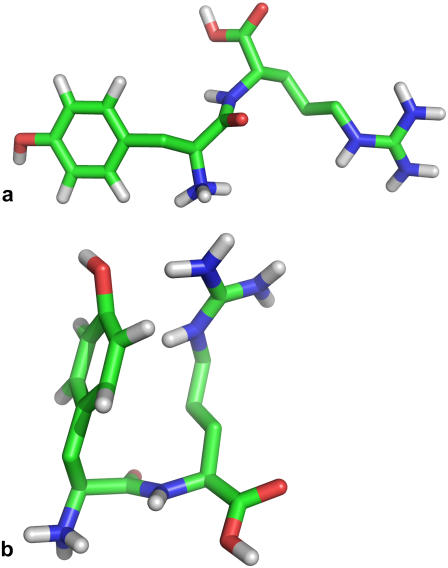

From these results, an obvious question arises, namely what kind of structures are being formed at lower and higher pH values. A possibility would be that conformational changes involve an interaction between the two side chains. For this interaction to take place, the correct alignment between the Cα and Cβ atoms of both residues would be of major importance. With this in mind, we monitored the dihedral angle formed between the atoms CβTyr-CαTyr-CαArg-CβArg. When KTP is in an extended conformation (Fig. 5 a), this dihedral angle takes values around 180° (trans), and when the side chains interact with each other (Fig. 5 b), the dihedral angle takes values around 0° (cis).

FIGURE 5.

Two typical conformations of KTP in water. (a) trans extended conformation; (b) cis packed conformation. The fully protonated form is represented.

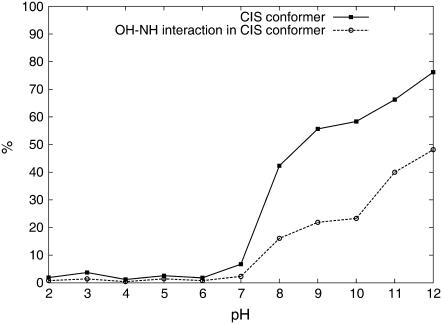

Our simulations indicate that KTP has a clear preference for the cis conformation upon pH increase (Fig. 6). Interestingly, at relatively low pH both the N- and C-terminus are charged and KTP is preferably in the trans conformation, keeping both termini far apart. Upon pH increase, the N-terminus looses the charge and KTP prefers the cis conformations. These results might seem contradictory at first glance because opposite charges should attract each other. However, these groups are very exposed to water, and thus solvation can easily overcome this attraction (see Suppl. Mat.). In fact, salt bridges between solvent-exposed groups are usually very weak (87,88), often breaking during simulations (89,90).

When looking at the histogram surface (Fig. 6), two distinct populations can be separated from each other. We considered a conformation to be cis if the dihedral angle is between −70° and 100°, and trans otherwise. In this way, we can quantify the amount of cis KTP at different pH values (Fig. 7, solid squares). From these results, it is clear that the trans/cis transition is induced not only by the deprotonation of the N-terminus (pH 7–8) but also by the deprotonation of the Tyr-OH (pH 10–11).

FIGURE 7.

Percentage of cis conformations over pH (solid squares) and the percentage of cis conformations with Tyr-Arg interactions (cutoff = 6 Å) (dashed circles).

The interaction of the side chains was monitored by following the distance between Tyr-OH and the closest Arg- NH atoms. From the minima in the histograms (data not shown), we chose a cutoff of 6 Å to define an interaction, and used this criterion to determine the number of cis conformations with packed side chains (Fig. 7, dashed circles). These results show that there is a very relevant number of cis conformations in which one or both of the side chains prefer to be solvated rather than interact with each other.

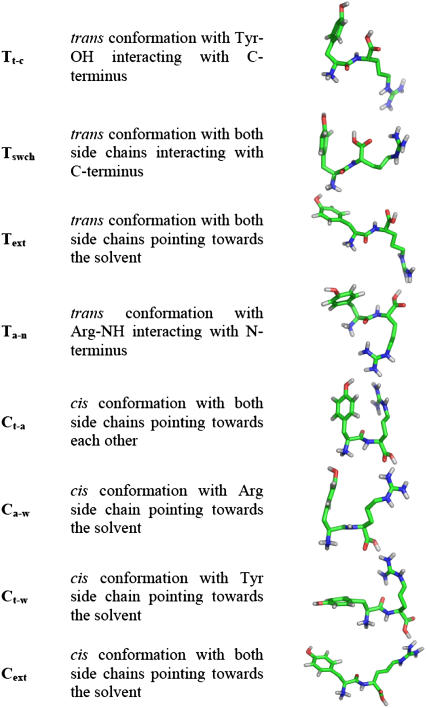

Detailed conformational analysis with PCA

From analysis of the dihedral angle CB-CA-CA-CB we observed that there is a clear transition from trans to cis upon pH increase, but the question remains whether all trans and cis conformers are in extended or packed conformations. In Fig. 7, we showed that there are cis conformers with noninteracting side chains. To better characterize the occurring conformations, we did a PCA analysis at different pH values, whose results are shown in Fig. 8 and Table 2. We observe that at very low pH values, the C-terminus is protonated, leading to the preference for a trans conformation with Tyr-OH interacting with the C-terminus (Tt-c). The Tswch conformation seems to be a particular case of the Tt-c peak where the Arg's side chain is also interacting with the C-terminus. With the increase of pH, the C-terminus deprotonates and prefers to become solvated, favoring the trans conformation with both side chains pointing toward the solvent (Text). Above pH 8.0, the N-terminus is mainly deprotonated, which favors the formation of cis conformers. PCA was able to identify at least four distinct cis peaks, with the differences lying in the positions of the side chains. By far the largest peak is the one where both side chains are pointing toward each other (Ct-a). The conformations where one or both the side chains are pointing toward the solvent (Ct-w, Ca-w, and Cext) can be seen as transient. At very high pH values, the Arg side chain deprotonates and allows an interaction between Arg-NH and the N-terminus in a trans conformation (Ta-n).

FIGURE 8.

Representative conformations from most populated peaks. The fully protonated forms are represented.

TABLE 2.

Population percentage of each conformational peak at different pH values

| pH

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structure | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| Tt-c | 80.7 | 71.1 | 51.4 | 29.3 | 25.5 | 12.8 | 2.4 | — | — | — | — |

| Tswch | — | 6.0 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Text | 17.1 | 18.2 | 47.7 | 68.5 | 72.3 | 84.4 | 56.6 | 43.6 | 42.9 | 33.1 | 20.8 |

| Ta-n | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 2.4 | 4.5 |

| Ct-a | 1.6 | 4.2 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 1.9 | 34.0 | 42.2 | 44.7 | 54.1 | 66.8 |

| Ca-w | — | — | — | — | — | 0.5 | 3.9 | 2.7 | 8.0 | 10.1 | 4.7 |

| Ct-w | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1.2 | 2.2 | 2.3 | — | 2.1 |

| Cext | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1.6 | 8.8 | 1.7 | — | 1.0 |

These PCA results are in good agreement with the cluster-analysis study of Lopes et al. (74), which reports that the main conformation clusters obtained for the charged and neutral N-terminus states were, respectively, the Text and the Ct-a conformers (using the nomenclature discussed above).

Conformational fit to morphine

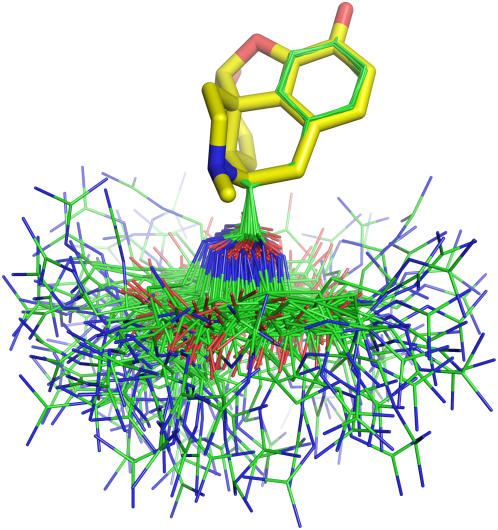

Morphine is a pentacyclic compound where almost all atoms are constrained with little freedom. Part of the structure of KTP has a strong resemblance to morphine. In fact, the Tyr residue at the N-terminus of KTP can be mapped on morphine, fully matching its aromatic ring, as well as part of its cyclohexane and piperidine rings. For the conformational fit, we computed the non-mass-weighted root mean-square deviation (RMSD) between all the conformations at all pH values (1.1 × 106), and the morphine structure taken from its complex with an antimorphine antibody (PDB code 1Q0Y) (91). In this calculation, the atoms N, CA, CB, CG, CD1, CD2, CE1, CE2, CZ, and OH were considered. Due to the possible rotation of the phenol ring, two RMSD calculations were done for each conformation (CD1-CE1 exchanged with CD2-CE2), and the lowest value was chosen. Since most of the superimposed atoms are geometrically constrained by the phenol ring, the RMSD value essentially measures the different orientation of the N and CA atoms in both molecules. In this way, we obtained an RMSD value of 1.083 Å for the worse fit and a value of 0.142 Å for the best fit. When a cutoff of 0.2 Å was applied, we obtained 156 structures (0.014%) which showed an almost perfect overlap with morphine (Fig. 9). This shows that KTP can fulfill the structural constraints present in morphine. In this set of conformers, there are conformations coming from all pH values, with no clear preference for any particular one (data not shown). There is also no preference for any cis or trans conformation (data not shown). Fig. 9 also shows that a very good fit to morphine turns out to select conformers in which the Arg side chain never approaches the phenol ring, nor even the morphine template.

FIGURE 9.

Fit of the 156 best conformations of KTP (lines, carbons in green) to the structure of morphine (sticks, carbons in yellow). All protons are omitted for clarity.

CONCLUSIONS

We have reported a full conformational study of KTP at different pH values, using a constant-pH MD simulation method. We showed that KTP does not have a unique structure in aqueous solution and that the pKa values are not significantly shifted from those of the individual amino acids. Furthermore, ionic strength does not have a relevant effect on the titration curves.

The protonation of the N-terminus amine is a preponderant factor in the definition of both the charge and the conformation of KTP for receptor interaction. Even though we predict a pKa of 7.14 for the amine, it is generally accepted that the pKa can be slightly higher close to the negatively charged membrane, and that the local pH should be lower than that of the cytoplasmatic (92). Therefore, it is likely that, when interacting with its receptor, KTP is mainly protonated at the N-terminus.

We observed that pH has a strong influence on KTP's conformational preferences. From the packing and the side-chain position studies, we were able to identify one of the most important conformational transitions in KTP: the preference for the cis in detriment of the trans conformations upon pH increase. The key points for this transition are the deprotonation of both the N-terminus and the Tyr-OH sites. With PCA, we were able to characterize the different populations within the cis and trans groups. The two main populations were the trans extended conformation (Text) and the cis packed conformation with both side chains interacting with each other (Ct-a). Besides the low-populated peaks with a transient character (Tswch; Ct-w; Ca-w and Cext), the method was able to identify two populations that are only present at extreme pH values (Tt-c and Ta-n).

The structural information about the KTPr is scarce. We know that its binding pocket has to be different from the opioid receptors (53,62,73). Nevertheless, there are certain features in KTP that are common to the opioid analgesics, and which may direct the interaction with its receptor: 1), the phenolic ring can interact with the receptor both by π-stacking and hydrogen bonding; and 2), the N-terminus amine group, when protonated, can make an ionic bond with an acidic residue in the receptor. Another important aspect of the KTP-receptor interaction is orientation. The question of whether KTP can adopt the correct orientation for receptor binding is difficult to answer due to the absence of structural information on the receptor. By fitting the KTP conformations to the structure of morphine, we tried to exclude the hypothesis that the KTPr pocket is similar to that of the μ-receptor. Interestingly, we observed exactly the opposite. The best-fitted KTP conformations revealed several nonobvious aspects: 1), there was no preference for any N-terminus charge or cis/trans conformation in the set; and 2), the predominance of the extended conformations (both cis and trans) results in the Arg side chain not invading the vicinities of the phenol group of the Tyr, allowing this to be presented to the receptor without any hindering effects. These results suggest that, despite the fact that KTP does not bind to the opioid receptors, there is no indication for the KTPr pocket to be very different from those of the opioid receptors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

An online supplement to this article can be found by visiting BJ Online at http://www.biophysj.org.

Acknowledgments

We thank Cláudio M. Soares for helpful discussions, Sara R. R. Campos for help with the PCA analysis, and Paulo J. Martel for providing a modified version of the g_rms GROMACS program.

We acknowledge financial support from Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, Portugal, through fellowship SFRH/BPD/14540/2003 and grant POCTI/BME/45810/2002.

References

- 1.Stryer, L. 1995. Biochemistry, 4th ed. Freeman, New York.

- 2.Dyson, H. J., and P. E. Wright. 1991. Defining solution conformations of small linear peptides. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biophys. Chem. 20:519–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aburi, M., and P. E. Smith. 2002. A conformational analysis of leucine enkephalin as a function of pH. Biopolymers. 64:177–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Warwicker, J., and H. C. Watson. 1982. Calculation of the electric-potential in the active-site cleft due to α-helix dipoles. J. Mol. Biol. 157:671–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharp, K. A., and B. Honig. 1990. Electrostatic interactions in macromolecules: theory and applications. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biophys. Chem. 19:301–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bashford, D., and M. Karplus. 1990. pKa's of ionizable groups in proteins: atomic detail from a continuum electrostatic model. Biochemistry. 29:10219–10225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang, A. S., M. R. Gunner, R. Sampogna, K. Sharp, and B. Honig. 1993. On the calculation of pKa's in proteins. Proteins Struct. Funct. Genet. 15:252–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simonson, T. 2001. Macromolecular electrostatics: continuum models and their growing pains. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 11:243–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bashford, D. 2004. Macroscopic electrostatic models for protonation states in proteins. Front. Biosci. 9:1082–1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beroza, P., and D. A. Case. 1996. Including side chain flexibility in continuum electrostatic calculations of protein titration. J. Phys. Chem. 100:20156–20163. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Demchuk, E., and R. C. Wade. 1996. Improving the continuum dielectric approach to calculating pKas of ionizable groups in proteins. J. Phys. Chem. 100:17373–17387. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Georgescu, R. E., E. G. Alexov, and M. R. Gunner. 2002. Combining conformational flexibility and continuum electrostatics for calculating pKas in proteins. Biophys. J. 83:1731–1748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bashford, D., and D. A. Case. 2000. Generalized Born models of macromolecular solvation effects. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 51:129–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feig, M., and C. L. Brooks. 2004. Recent advances in the development and application of implicit solvent models in biomolecule simulations. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 14:217–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luo, R., M. S. Head, J. Moult, and M. K. Gilson. 1998. pKa shifts in small molecules and HIV protease: electrostatics and conformation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120:6138–6146. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee, F. S., Z. T. Chu, and A. Warshel. 1993. Microscopic and semimicroscopic calculations of electrostatic energies in proteins by the Polaris and Enzymix programs. J. Comput. Chem. 14:161–185. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sham, Y. Y., Z. T. Chu, and A. Warshel. 1997. Consistent calculations of pKa's of ionizable residues in proteins: semi-microscopic and microscopic approaches. J. Phys. Chem. B. 101:4458–4472. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wisz, M. S., and H. W. Hellinga. 2003. An empirical model for electrostatic interactions in proteins incorporating multiple geometry-dependent dielectric constants. Proteins Struct. Funct. Genet. 51:360–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li, H., A. W. Hains, J. E. Everts, A. D. Robertson, and J. H. Jensen. 2002. The prediction of protein pKa's using QM/MM: The pKa of lysine 55 in turkey ovomucoid third domain. J. Phys. Chem. B. 106:3486–3494. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mehler, E. L., and F. Guarnieri. 1999. A self-consistent, microenvironment modulated screened coulomb potential approximation to calculate pH-dependent electrostatic effects in Proteins. Biophys. J. 75:3–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Del Buono, G. S., F. E. Figueirido, and R. M. Levy. 1994. Intrinsic pKas of ionizable residues in proteins: an explicit solvent calculation for lysozyme. Proteins: Struct. Funct. Genet. 20:85–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jorgensen, W. L., and J. M. Briggs. 1989. A priori pKa calculations and the hydration of organic anions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 111:4190–4197. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen, J. L., L. Noodleman, and D. Bashford. 1994. Incorporating solvation effects into density functional electronic structure calculations. J. Phys. Chem. 98:11059–11068. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Topol, I. A., G. J. Tawa, S. K. Burt, and A. A. Rashin. 1997. Calculation of absolute and relative acidities of substituted imidazoles in aqueous solvent. J. Phys. Chem. A. 101:10075–10081. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Antosiewicz, J., and D. Porschke. 1989. The nature of protein dipole-moments-experimental and calculated permanent dipole of α-chymotrypsin. Biochemistry. 28:10072–10078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beroza, P., D. R. Fredkin, M. Y. Okamura, and G. Feher. 1991. Protonation of interacting residues in a protein by a Monte Carlo method: application to lysozyme and the photosynthetic reaction center of Rhodobacter-sphaeroides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 88:5804–5808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baptista, A. M., P. J. Martel, and C. M. Soares. 1999. Simulation of electron-proton coupling with a Monte Carlo method: application to cytochrome c3 using continuum electrostatics. Biophys. J. 76:2978–2998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tanford, C., and R. Roxby. 1972. Interpretation of protein titration curves: application to lysozyme. Biochemistry. 11:2192–2198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gilson, M. K. 1993. Multiple-site titration and molecular modeling: two rapid methods for computing energies and forces for ionizable groups in proteins. Proteins Struct. Funct. Genet. 15:266–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spassov, V. Z., and D. Bashford. 1999. Multiple-site ligand binding to flexible macromolecules: separation of global and local conformational change and an iterative mobile clustering approach. J. Comput. Chem. 20:1091–1111. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bashford, D., and M. Karplus. 1991. Multiple-site titration curves of proteins: an analysis of exact and approximate methods for their calculation. J. Phys. Chem. 95:9556–9561. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eberini, I., A. M. Baptista, E. Gianazza, F. Fraternali, and T. Beringhelli. 2004. Reorganization in apo- and holo-β-lactoglobulin upon protonation of Glu89: molecular dynamics and pKa calculations. Proteins. 54:744–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Warshel, A., and J. Åqvist. 1991. Electrostatic energy and macromolecular function. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biophys. Chem. 20:267–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sham, Y. Y., I. Muegge, and A. Warshel. 1998. The effect of protein relaxation on charge-charge interactions and dielectric constants of proteins. Biophys. J. 74:1744–1753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Simonson, T., G. Archontis, and M. Karplus. 1999. A Poisson-Boltzmann study of charge insertion in an enzyme active site: the effect of dielectric relaxation. J. Phys. Chem. B. 103:6142–6156. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Archontis, G., and T. Simonson. 2005. Proton binding to proteins: A free-energy component analysis using a dielectric continuum model. Biophys. J. 88:3888–3904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mertz, J. E., and B. M. Pettitt. 1994. Molecular-dynamics at a constant pH. Int. J. Supercomput. Ap. 8:47–53. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baptista, A. M., P. J. Martel, and S. B. Petersen. 1997. Simulation of protein conformational freedom as a function of pH: constant-pH molecular dynamics using implicit titration. Proteins Struct. Funct. Genet. 27:523–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baptista, A. M., V. H. Teixeira, and C. M. Soares. 2002. Constant-pH molecular dynamics using stochastic titration. J. Chem. Phys. 117:4184–4200. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Walczak, A. M., and J. M. Antosiewicz. 2002. Langevin dynamics of proteins at constant pH. Phys. Rev. E. 66:051911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dlugosz, M., J. M. Antosiewicz, and A. D. Robertson. 2004. Constant-pH molecular dynamics study of protonation-structure relationship in a heptapeptide derived from ovomucoid third domain. Phys. Rev. E. 69:021915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dlugosz, M., and J. M. Antosiewicz. 2004. Constant-pH molecular dynamics simulations: a test case of succinic acid. Chem. Phys. 302:161–170. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mongan, J., D. A. Case, and J. A. McCammon. 2004. Constant pH molecular dynamics in generalized Born implicit solvent. J. Comput. Chem. 25:2038–2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Burgi, R., P. A. Kollman, and W. F. van Gunsteren. 2002. Simulating proteins at constant pH: An approach combining molecular dynamics and Monte Carlo simulation. Proteins Struct. Funct. Genet. 47:469–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Börjesson, U., and P. H. Hünenberger. 2001. Explicit-solvent molecular dynamics simulation at constant pH: methodology and application to small amines. J. Chem. Phys. 114:9706–9719. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Börjesson, U., and P. H. Hünenberger. 2004. pH-dependent stability of a decalysine α-helix studied by explicit-solvent molecular dynamics simulations at constant pH. J. Phys. Chem. B. 108:13551–13559. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baptista, A. M. 2001. Comment on “Explicit-solvent molecular dynamics simulation at constant pH: methodology and application to small amines”. J. Chem. Phys. 116:7766. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee, M. S., F. R. Salsbury, and C. L. Brooks. 2004. Constant-pH molecular dynamics using continuous titration coordinates. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinf. 56:738–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Khandogin, J., and C. L. Brooks. 2005. Constant pH molecular dynamics with proton tautomerism. Biophys. J. 89:141–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Machuqueiro, M., and A. M. Baptista. 2006. Constant-pH molecular dynamics with ionic strength effects: protonation-conformation coupling in decalysine. J. Phys. Chem. B. 110:2927–2933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Takagi, H., H. Shiomi, H. Ueda, and H. Amano. 1979. Morphine-like analgesia by a new dipeptide, L-tyrosyl-L-arginine (kyotorphin) and its analog. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 55:109–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ueda, H., H. Shiomi, and H. Takagi. 1980. Regional distribution of a novel analgesic dipeptide kyotorphin (Tyr-Arg) in the rat-brain and spinal-cord. Brain Res. 198:460–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Takagi, H., H. Shiomi, H. Ueda, and H. Amano. 1979. Novel analgesic dipeptide from bovine brain is a possible Met-enkephalin releaser. Nature. 282:410–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shiomi, H., H. Ueda, and H. Takagi. 1981. Isolation and identification of an analgesic opioid dipeptide kyotorphin (Tyr-Arg) from bovine brain. Neuropharmacology. 20:633–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ueda, H., Y. Yoshihara, A. Nakamura, H. Shiomi, M. Satoh, and H. Takagi. 1985. How is kyotorphin (Tyr-Arg) generated in the brain. Neuropeptides. 5:525–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ueda, H., Y. Yoshihara, and H. Takagi. 1986. A putative met-enkephalin releaser, kyotorphin enhances intracellular Ca2+ in the synaptosomes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 137:897–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ueda, H., Y. Yoshihara, N. Fukushima, H. Shiomi, A. Nakamura, and H. Takagi. 1987. Kyotorphin (tyrosine-arginine) synthetase in rat-brain synaptosomes. J. Biol. Chem. 262:8165–8173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Karelin, A. A., M. M. Philippova, and V. T. Ivanov. 1995. Proteolytic degradation of hemoglobin in erythrocytes leads to biologically-active peptides. Peptides. 16:693–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fukui, K., H. Shiomi, H. Takagi, K. Hayashi, Y. Kiso, and K. Kitagawa. 1983. Isolation from bovine brain of a novel analgesic pentapeptide, neo-kyotorphin, containing the Tyr-Arg (kyotorphin) unit. Neuropharmacology. 22:191–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Amano, H., Y. Morimoto, S. Kaneko, and H. Takagi. 1984. Opioid activity of enkephalin analogs containing the kyotorphin-related structure in the N-terminus. Neuropharmacology. 23:395–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ueda, H., G. Ming, T. Hazato, T. Katayama, and H. Takagi. 1985. Degradation of kyotorphin by a purified membrane-bound-aminopeptidase from monkey brain: potentiation of kyotorphin-induced analgesia by a highly effective inhibitor, bestatin. Life Sci. 36:1865–1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ueda, H., M. Inoue, G. Weltrowska, and P. W. Schiller. 2000. An enzymatically stable kyotorphin analog induces pain in subattomol doses. Peptides. 21:717–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ueda, H., and M. Inoue. 2000. In vivo signal transduction of nociceptive response by kyotorphin (tyrosine-arginine) through Gαi and inositol trisphosphate-mediated Ca2+ influx. Mol. Pharmacol. 57:108–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ueda, H., Y. Yoshihara, H. Misawa, N. Fukushima, T. Katada, M. Ui, H. Takagi, and M. Satoh. 1989. The kyotorphin (tyrosine-arginine) receptor and a selective reconstitution with purified Gi, measured with GTPase and phospholipase-C assays. J. Biol. Chem. 264:3732–3741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shiomi, H., Y. Kuraishi, H. Ueda, Y. Harada, H. Amano, and H. Takagi. 1981. Mechanism of kyotorphin-induced release of met-enkephalin from guinea-pig striatum and spinal-cord. Brain Res. 221:161–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Arima, T., Y. Kitamura, T. Nishiya, T. Taniguchi, H. Takagi, and Y. Nomura. 1997. Effects of kyotorphin (L-tyrosyl-L-arginine) on [3H]NG-nitro-L-arginine binding to neuronal nitric oxide synthase in rat brain. Neurochem. Int. 30:605–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.George, S. R., T. Fan, Z. D. Xie, R. Tse, V. Tam, G. Varghese, and B. F. O'Dowd. 2000. Oligomerization of μ- and δ-opioid receptors: generation of novel functional properties. J. Biol. Chem. 275:26128–26135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li, Y., Y. Saito, M. Suzuki, H. Ueda, M. Endo, and K. Maruyama. 2006. Kyotorphin has a novel action on rat cardiac muscle. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 339:805–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lapalu, S., C. Moisand, H. Mazarguil, G. Cambois, C. Mollereau, and J. C. Meunier. 1997. Comparison of the structure-activity relationships of nociceptin and dynorphin A using chimeric peptides. FEBS Lett. 417:333–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lapalu, S., C. Moisand, J. L. Butour, C. Mollereau, and J. C. Meunier. 1998. Different domains of the ORL1 and κ-opioid receptors are involved in recognition of nociceptin and dynorphin A. FEBS Lett. 427:296–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zacharias, N., and D. A. Dougherty. 2002. Cation-π interactions in ligand recognition and catalysis. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 23:281–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Patrick, G. L. 2001. An Introduction to Medicinal Chemistry, 2nd ed. Oxford University Press, New York, 511–550.

- 73.Hansen, D. W., A. Stapelfeld, M. A. Savage, M. Reichman, D. L. Hammond, R. C. Haaseth, and H. I. Mosberg. 1992. Systemic analgesic activity and δ-opioid selectivity in [2,6-dimethyl-Tyr1, D-Pen2, D-Pen5]enkephalin. J. Med. Chem. 35:684–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lopes, S. C. D. N., C. M. Soares, A. M. Baptista, E. Goormaghtigh, B. J. C. Cabral, and M. A. R. B. Castanho. 2006. Conformational and orientational guidance of the analgesic dipeptide kyotorphin induced by lipidic membranes: putative correlation toward receptor docking. J. Phys. Chem. B. 110:3385–3394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bashford, D., and K. Gerwert. 1992. Electrostatic calculations of the pKa values of ionizable groups in bacteriorhodopsin. J. Mol. Biol. 224:473–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Scott, W. R. P., P. H. Hünenberger, I. G. Tironi, A. E. Mark, S. R. Billeter, J. Fennen, A. E. Torda, T. Huber, P. Kruger, and W. F. van Gunsteren. 1999. The GROMOS biomolecular simulation program package. J. Phys. Chem. A. 103:3596–3607. [Google Scholar]

- 77.van Gunsteren, W. F., and H. J. C. Berendsen. 1990. Computer-simulation of molecular-dynamics: methodology, applications, and perspectives in chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 29:992–1023. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gilson, M. K., K. A. Sharp, and B. Honig. 1987. Calculating the electrostatic potential of molecules in solution: method and error assessment. J. Comput. Chem. 9:327–335. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Berendsen, H. J. C., D. van der Spoel, and R. Van Drunen. 1995. GROMACS: a message-passing parallel molecular-dynamics implementation. Comput. Phys. Commun. 91:43–56. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lindahl, E., B. Hess, and D. van der Spoel. 2001. GROMACS 3.0: a package for molecular simulation and trajectory analysis. J. Mol. Model. (Online). 7:306–317. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hermans, J., H. J. C. Berendsen, W. F. van Gunsteren, and J. P. M. Postma. 1984. A consistent empirical potential for water-protein interactions. Biopolymers. 23:1513–1518. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tironi, I. G., R. Sperb, P. E. Smith, and W. F. van Gunsteren. 1995. A generalized reaction field method for molecular-dynamics simulations. J. Chem. Phys. 102:5451–5459. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Berendsen, H. J. C., J. P. M. Postma, W. F. van Gunsteren, A. Dinola, and J. R. Haak. 1984. Molecular dynamics with coupling to an external bath. J. Chem. Phys. 81:3684–3690. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Allen, M. P., and D. J. Tildesley. 1987, Computer Simulations of Liquids. Oxford University Press, New York.

- 85.Jolliffe, I. T. 2002, Principal Components Analysis, 2nd ed. Springer-Verlag, New York.

- 86.Silverman, B. W. 1986, Density Estimation for Statistics and Data Analysis. Chapman & Hall/CRC, London.

- 87.Serrano, L., J. T. Jr. Kellis, P. Cann, A. Matouschek, and A. R. Fersht. 1992. The folding of an enzyme. II. Substructure of barnase and the contribution of different interactions to protein stability. J. Mol. Biol. 224:783–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hendsch, Z. S., and B. Tidor. 1994. Do salt bridges stabilize proteins? A continuum electrostatic analysis. Protein Sci. 3:211–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Caflisch, A., and M. Karplus. 1995. Acid and thermal denaturation of barnase investigated by molecular dynamics simulations. J. Mol. Biol. 252:672–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tirado-Rives, J., and W. L. Jorgensen. 1991. Molecular dynamics simulations of an α-helical analogue of RNAse AS-peptide in water. Biochemistry. 30:3864–3871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Pozharski, E., M. A. Wilson, A. Hewagama, A. B. Shanafelt, G. Petsko, and D. Ringe. 2004. Anchoring a cationic ligand: the structure of the Fab fragment of the anti-morphine antibody 9B1 and its complex with morphine. J. Mol. Biol. 337:691–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Cevc, G., and D. Marsh. 1987. Solute-bilayer interactions, binding, and transport. In Phospholipid Bilayers. Physical Principles and Models. E. E. Bittar, ed. John Wiley and Sons, New York.