Abstract

Somatic cell clones often fail at a developmental stage coincident with commencement of differentiation. The transcription factor Oct4 is expressed during cleavage stages and is essential for the differentiation of the blastocyst. Oct4 expression becomes restricted to the inner cell mass and epiblast. After gastrulation Oct4 is active only in germ cells and is silent in somatic cells. Here, Oct4 and an Oct4–GFP transgene were used as markers for which gene reprogramming could be directly related to the developmental potential of somatic cell clones. Cumulus cell clones initiated Oct4 expression at the correct stage but showed an incorrect spatial expression in the majority of blastocysts. The ability of clones to form outgrowths was reduced, and the outgrowths had low or even undetectable levels of Oct4 RNA or GFP. The quality of GFP signals in blastocysts correlated with the ability to generate outgrowths that maintain GFP expression and the frequency of embryonic stem (ES) cell derivation. Abnormal Oct4 expression in clones is either directly or indirectly caused by reprogramming errors and is indicative of a general failure to reset the genetic program. The abnormal Oct4 expression may be associated with aberrant expression of other crucial developmental genes, leading to abnormalities at various embryonic stages. Regardless of other genes, the variations observed in Oct4 levels alone account for the majority of failures currently observed for somatic cell cloning.

Keywords: Oct4, pluripotency, Oct4–GFP transgene, gene reprogramming failure, nuclear transfer, blastocyst stage clones

Normal development and adulthood are definite measures of successful nuclear reprogramming in somatic cell cloning. However, development rates to term are extremely low in the mammalian species that have been cloned so far, particularly in the mouse (<3%; Wakayama and Yanagimachi 1999b). In mammalian clones, it has been consistently observed that the majority of developmental attrition occurs early in pregnancy (Solter 2000). Typically, less than half of all somatic cell clones develop to the blastocyst stage. Of those, less than one-third develop beyond implantation. In the mouse, it has been observed that the vast majority of somatic cell clones transferred in vivo at the morula/blastocyst stage did not develop past 6–7 days postcoitum (dpc; Wakayama and Yanagimachi 2001), and implantation rates are <10% of embryos transferred (Kishikawa et al. 1999). Therefore, most clones are not able to develop past the late preimplantation or early postimplantation stages. The basis for failure is unknown.

A favored hypothesis for the developmental incompetence of clones is inadequate reprogramming of the transplanted nucleus to a state equivalent to that of an early embryonic nucleus. To detect changes in the nucleus upon transfer into a recipient oocyte, studies have focused on morphology, gene expression, and genomic methylation. Several studies have shown that the transplanted nucleus undergoes extensive morphological changes such as nuclear swelling, dispersal of nucleoli, nuclear envelope breakdown, and premature chromosome condensation. These observations were made following transfer of embryonic (Stice and Robl 1988; Prather et al. 1989; Collas and Robl 1991; Kanka et al. 1991) as well as somatic (Czolowska et al. 1984) nuclei. Global changes in transcriptional activity of the transplanted nuclei have also been observed (Kanka et al. 1996; Schultz et al. 1996; Smith et al. 1996; Lavoir et al. 1997). Expression analysis using RT-PCR revealed similar patterns of transcription between clones and fertilized embryos in porcine (β-actin–GFP; Koo et al. 2001) and bovine preimplantation embryos (TEC-3; van Stekelenburg-Hamers et al. 1994); Oct4, FGF2, FGFr2, gp130, and poly(A) polymerase (Daniels et al. 2000); lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), citrate synthase, and phosphofructokinase (PFK; Winger et al. 2000). In blastocyst stage bovine clones, aberrant gene expression has been detected for several genes—increase of Mash2; decrease of DNMT; absence of Hsp70; and variability of INFτ (Wrenzycki et al. 2001), FGF4, and IL6 in clones derived from granulosa (Daniels et al. 2000) but not from fetal epithelial cells (Daniels et al. 2001). None of these studies, however, can attribute the large proportion of clones failing around the time of implantation to altered gene expression profiles. Epigenetic studies revealed mostly normal X-chromosome inactivation (Eggan et al. 2000; Wrenzycki et al. 2002) but showed methylation instability at specific CpG islands in cloned mouse embryos obtained from somatic (Ohgane et al. 2001) and embryonic stem (ES) cells (Humpherys et al. 2001). Studies on epigenetic changes have also been conducted on the small proportion of clones that become fetuses or develop to term, indicating that imprinting is largely normal or that mammalian development is tolerant of epigenetic aberrations (Humpherys et al. 2001; Inoue et al. 2002).

Few genes have been shown both to be essential during preimplantation development and to exhibit an early embryonic phenotype. Oct4 encodes a transcription factor required for mouse embryo development past the blastocyst stage (Ovitt and Schöler 1998). Oct4 influences several genes expressed during early development, including Fgf4, Rex-1, Sox-2, OPN, hCG, Utf-1 (Pesce and Schöler 2001), INFτ (Ezashi et al. 2001) and other putative downstream genes, Creatine kinase B, Makorin 1, Importin β, Histone H2A.Z, and Ribosomal protein S7 (Du et al. 2001). Fgf4 is a target gene of Oct4 (Dailey et al. 1994; Yuan et al. 1995; Botquin et al. 1998), and is one of the few genes found to have aberrant levels in cloned bovine blastocysts (Daniels et al. 2000, 2001). In the mouse, Oct4 expression begins at the 4- to 8-cell stage and becomes restricted to inner cell mass (ICM) cells of the blastocyst and then to the epiblast, founder cells of the embryo proper (Palmieri et al. 1994). After gastrulation, Oct4 expression is restricted to the germ cell lineage (Yeom et al. 1996; for review, see Pesce et al. 1998). Although mouse embryos homozygous for a targeted deletion of Oct4 can develop into structures resembling blastocysts (Nichols et al. 1998), they do not form a pluripotent ICM and die shortly after implantation from an inability to differentiate into embryonic lineages. In vitro, variations in the level of Oct4 expression, as little as 30% above or below the normal level, regulate the differentiation of embryonic stem cells into putative endoderm or trophectoderm (TE), respectively (Niwa et al. 2000). Thus, subtle changes in Oct4 expression have predictable consequences for the early postimplantation embryo.

The aim of the present study was to follow the reprogramming of cellular potency in clones, from the differentiated state of the nucleus donor cell to the pluripotent state of the ICM cell, using Oct4 as a marker. Development to cleavage stages is a limited indicator for assessing potency and viability, because a large proportion of morula-stage clones does not form blastocysts. The blastocyst stage obviously has more potential for further development, and, hence, represents a useful stage at which to assess reprogramming of a gene essential for subsequent development. The blastocyst stage also has the advantage of being the first stage with distinct lineages—ICM and TE. Practically, it is the last stage that can be analyzed in vitro prior to transfer into the uterus. Furthermore, the blastocyst stage is required for the generation of ES cell lines from clones for therapeutic purposes.

Blastocysts were cloned from somatic cell nuclei (not expressing Oct4) and germ cell nuclei (already expressing Oct4). Developmental rates and Oct4 expression of clones were compared with those of synchronous blastocysts produced by in vitro fertilization (IVF) and intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), as a control group independent of cloning but involving micromanipulation. The developmental prospects of cumulus-cell-cloned blastocysts were subsequently evaluated in vitro and in vivo. A minor proportion of blastocyst-stage clones and subsequent outgrowths showed a normal Oct4 pattern. In the majority of clones, Oct4 transcripts were distributed abnormally in both mosaic and ectopic patterns. This suggests that reprogramming also occurs after the first cleavage and is not restricted to the metaphase oocyte cytoplasm. Furthermore, Oct4–GFP (Szabó et al. 2002) in blastocysts correlates with the ability of blastocysts to form outgrowths and with formation of outgrowths that maintain an Oct4–GFP signal. These findings are consistent with the hypothesis that the failure of cloned mouse embryos to develop past implantation is related to an incorrect lineage determination in the blastocyst as directed by Oct4.

Results

Development of clones in vivo and in vitro

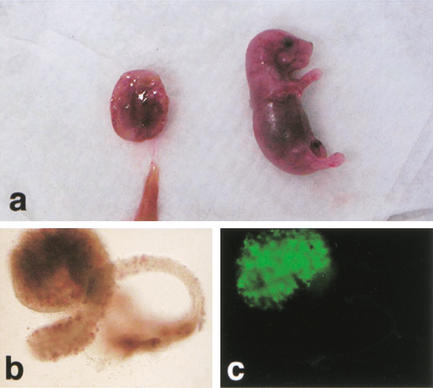

Reprogramming of a somatic cell nucleus after transplantation into an ooplasm can at least in part be measured by the subsequent development of the clone. To assay the success of reprogramming in cumulus cell clones, we first analyzed development in vivo and during preimplantation development in vitro. Clones were constructed by injection of Oct4–GFP transgenic and wild-type cumulus cell nuclei into enucleated oocytes. Of the clones produced, >80% survived manipulation and underwent the first cleavage to the two-cell stage (Table 1). Of 1472 clones transferred to 41 recipients, 24 of the recipients became pregnant and seven fetuses were recovered at midgestation (Table 1). From additional transfers of 173-morula-stage clones to eight recipients, four recipients became pregnant and two pups were recovered at term. The genotype of the pups was verified by visualizing Oct4–GFP in germ cells within the gonads. In the pups, Oct4–GFP was only detected in germ cells, not in any other tissue, indicating appropriate regulation of expression of a gene that was previously silent in the somatic-cell donor nucleus (Fig. 1). To determine whether our system was optimal for micromanipulation and culture, we generated embryos by ICSI. Transfer of ICSI embryos in vivo resulted in development to term at rates comparable to previous studies (Table 1; Kimura and Yanagimachi 1995).

Table 1.

In vivo development of Oct4–GFP clones and ICSI embryos

| Nucleus donor

|

Reconstructed oocytes n

|

Transferred two-cell stage n (%)

|

Pregnancies/recipients n

|

Decidua 10.5 dpc n (%)

|

Fetuses 10.5 dpc n

|

Replicates n

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cumulus cell | 1792 | 1472 (82) | 24/41 | 105 (7.1) | 7 | 19 |

| Germ cell | 425 | 349 (82) | 14/20 | 136 (32.0) | 2 | 6 |

| ICSI | 122 | 117 (96) | 5/7 | 19a (NA) | 8a + 18b | 2 |

NA: not applicable.

Partial, from two out of five pregnant females sacrified at midgestation.

Partial, number of live pups from the remaining three out of five pregnant females that were allowed to deliver.

Figure 1.

Term development of Oct4–GFP cumulus cell clones. (a) Female pup and placenta recovered 19.5 dpc; (b) Ovary (brightfield); (c) ovary (fluorescence), identifying Oct4–GFP-positive germ cells.

The rate of in vivo development for cumulus cell clones shown here is low, but is consistent with the general rates of development reported for somatic cell cloning in the mouse (Wakayama and Yanagimachi 2001). The number of fetuses developing was dramatically lower than the number of clones transferred into recipient mice. As indicated by the number of empty decidua, most clones failed to develop past implantation and were resorbed. Therefore, development of clones was assessed in vitro. Initial cleavage to the two-cell stage was similar for cumulus cell clones (80%), ICSI (71%), and IVF (culture control; 74%) embryos. However, in subsequent development to the morula and blastocyst stages, cumulus cell clones developed poorly (30% morula, 10% blastocyst) compared with IVF and ICSI (Table 2). Although cleavage is an indicator of development, the early stages of preimplantation development are largely supported by the oocyte cytoplasm. In contrast, development to the blastocyst stage cannot occur without substantial contribution from the zygotic genome. The blastocyst is the most meaningful preimplantation stage at which to analyze participation of the transplanted nucleus in development.

Table 2.

In vitro development of clones, IVF and ICSI embryos, and expression of GFP

| Nucleus donor

|

Reconstructed oocytes n

|

Two-cell stage n (%)

|

Morulae (% of 2 cells)

|

Blastocysts n (% of 2 cells)

|

GFP fluorescent blastocysts n (%)

|

Replicates n

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type nuclei | ||||||

| Cumulus cell | 1065 | 852 (80)a | 30 | 85 (10)a | NA | 20 |

| Oct4-GFP nuclei | ||||||

| Cumulus cell | 2513 | 1935 (77)ab | 30 | 165 (9)a | 135 (82)a | 39 |

| Germ cell | 603 | 500 (83)ac | 81 | 278 (56)b | 272 (98)b | 15 |

| IVF | 895e | 665 (74)d | 91 | 490 (74)c | 485 (99)b | 12 |

| ICSI | 1135f | 806 (71)d | 86 | 440 (55)b | 395 (90)c | 18 |

IVF, in vitro fertilized; ICSI, intracytoplasmic sperm injection; GFP, Green Fluorescent Protein; NA, not applicable.

Comparison of proportions (%) based on Student t test (two tails); superscripts a–d indicate significant difference (p < 0.05) between the values within the same column.

Inseminated.

Survived sperm injection.

Distribution and levels of Oct4 mRNA in clones

Oct4 is spatially and temporally regulated during preimplantation development but silent in somatic cells. Zygotic expression of Oct4 is initiated after the four-cell stage. At the blastocyst stage, Oct4 is down-regulated in the TE and maintained in the ICM (Fig. 2a). In the following experiments, we determined whether the silent state of Oct4 in the somatic nucleus could change to the active state in the preimplantation-stage embryo after nuclear transfer.

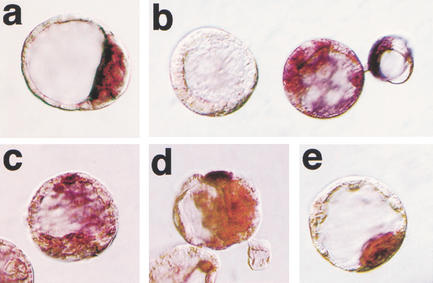

Figure 2.

Oct4 mRNA distribution in blastocysts. Whole-mount in situ hybridization. (a) Blastocyst-stage fertilized embryo showing restriction of Oct4 mRNA to the ICM caused by down-regulation of transcription in the TE. (b–e) Blastocyst-stage cumulus cell clones with lack of expression (b, left embryo), random expression in ICM and trophectoderm (b, right embryo; c, d), and ICM-specific expression (e). The color reaction in samples b–e was for 3 h to verify lack of signal in negative embryos.

Cumulus cell clones were evaluated for distribution of Oct4 mRNA at the blastocyst stage using in situ hybridization. Aberrant spatial distribution of Oct4 transcript was detected in the majority of clones. Restriction of Oct4 transcript to the ICM was observed in only 34% of somatic cell clones (Table 3). Patterns of abnormal Oct4 expression in clones included expression in both TE and ICM cells of the same embryo, as well as absence of expression in all cells (Fig. 2b–e). Although lack of Oct4 expression was observed at a similar frequency in IVF and ICSI embryos, ectopic expression was more frequent in somatic cell clones. In vitro culture did not have an impact on the spatial distribution of Oct4 mRNA, as indicated by in vivo fertilized but in vitro cultured embryos with ICM restriction in 93% of embryos analyzed (Table 3).

Table 3.

Expression of Oct4 in clone and control blastocysts

| Blastocyst type

|

n

|

Oct4 mRNA n (%)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICM restricted

|

ICM and TE

|

not detected

|

||

| Cumulus cell clone | 53d | 18 (34.0)a | 29 (54.7)a | 6 (11.3)a |

| IVF | 30 | 23 (76.7)b | 4 (13.3)b | 3 (10)a |

| ICSI | 80 | 60 (75.0)b | 9 (11.3)b | 11 (13.8)ab |

| In vivo fertilized | 75 | 70 (93.3)c | 3 (4.0)b | 2 (2.7)ac |

ICM, inner cell mass; TE, trophectoderm; NT, somatic cell clones; IVF, in vitro fertilized; ICSI, intracytoplasmic sperm injection.

Of 53 blastocysts, 8 were from B6C3 nuclei and 45 were from Oct4–GFP transgenic nuclei. Of the 45, 33 were GFP positive and 12 were GFP negative.

Comparison of proportions (%) based on Student t test (two tails); superscripts a–c indicate significant difference (P < 0.05) between the values within the same column.

Additionally, there were inter- as well as intraembryo variations in Oct4 mRNA expression levels (Figs. 2b–e, 3c). A common finding was a visibly lower level of Oct4 mRNA in clones than in the fertilized counterparts (Fig. 4).

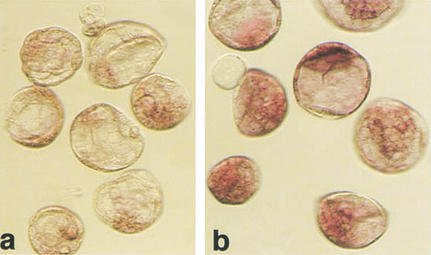

Figure 4.

Expression level of Oct4 in cumulus cell clones and fertilized blastocysts detected by in situ hybridization. Processing of embryos in the reaction was simultaneous, documentation after 1 h of color reaction. (a) Blastocyst-stage cumulus cell clones; (b) fertilized controls.

Oct4 expression in cloned blastocysts visualized by GFP

The observed lack of expression or improper spatial Oct4 distribution may be caused by a failure of onset of Oct4 gene expression in clones or down-regulation events in late preimplantation development. To distinguish between these possibilities, Oct4 expression in clones was monitored using the Oct4–GFP transgene. This was considered to be a suitable marker, as GFP correlates with Oct4 expression in preimplantation embryos (Palmieri et al. 1994; Yoshimizu et al. 1999). No difference was observed between Oct4–GFP transgenic and wild-type cumulus cell nuclei in the rate of blastocyst formation (Table 2). Cumulus cell nuclei transgenic for Oct4–GFP were transplanted, and GFP signal was observed during preimplantation development. When Oct4–GFP was expressed in clones, the onset was at the four- to eight-cell stage as observed in control Oct4–GFP transgenic embryos. However, 18% of somatic cell clones that developed to the blastocyst stage did not express Oct4–GFP at the four-cell or subsequent stages (Table 2; Fig. 3). This proportion is significantly higher than that observed with IVF embryos (Table 2). Presence of the transgene in the GFP-negative cloned blastocysts was ascertained by PCR, excluding loss of genetic material (e.g., aneuploidy) as the reason for absence of transgene expression.

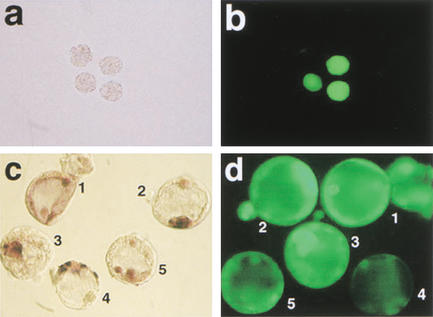

Figure 3.

Oct4 and Oct4–GFP in cumulus cell clones at preimplantation stages. (a,b) Oct4–GFP expression in cumulus cell clones at the morula stage. (a) Bright field morphology, (b) GFP fluorescence with examples of clones both expressing and lacking Oct4–GFP. (c,d) Whole-mount in situ hybridization for Oct4 mRNA (c) and GFP fluorescence (d) in clones at the blastocyst stage. Consistency between Oct4–GFP and Oct4 in situ signal is observed in embryos 2 and 3, whereas embryo 4 lacks GFP signal but shows strong Oct4 expression in trophectoderm cells. Embryos 1 and 5 lack an ICM-specific signal.

To delineate whether failure to initiate Oct4–GFP expression is due to the somatic nature of the nucleus or to the cloning procedure, we used cells expressing Oct4–GFP as nuclear donors. Clones were constructed with nuclei from Oct4–GFP transgenic fetal germ cells (13.5 to 16.5 dpc). Germ cell clones showed onset of Oct4–GFP expression at the four- to eight-cell stage; and GFP was present in 98% of clones developing to the blastocyst stage (Table 2). Germ cell clones had a higher proportion of both blastocyst and decidua formation than somatic cell clones. However, the rate of fetal development at midgestation was not superior to somatic cell clones (Table 1).

To determine whether the Oct4–GFP transgene, which is silent in somatic cell nuclei, was activated in a nondevelopmentally regulated pattern following nuclear transfer, clones were generated with fibroblast nuclei containing a lymphocyte-specific fusion transgene (CD8–GFP; Manjunath et al. 1999). In all clones constructed, GFP was not visible at preimplantation stages (188 oocytes injected; 173 two-cells; 66 morulae/blastocysts). Functionality of the CD8–GFP transgene was tested by exposing cloned embryos to trichostatin A (TSA) at the four-cell stage, resulting in the induction of GFP expression at the eight-cell stage. TSA is a histone deacetylase inhibitor that causes the nucleosomal structure of chromatin to relax (Thompson et al. 1995) and can facilitate transcription of silent genes.

In the majority of clones analyzed, Oct4–GFP signal was predictive of the presence of Oct4 mRNA. Only in rare cases did GFP-positive blastocysts lack Oct4 transcripts (2 of 33 blastocysts analyzed; Table 3), and, conversely, several blastocysts with very low or absent GFP were found to express Oct4 mRNA (8 of 12 GFP-negative blastocysts; 2 had an ICM-restricted signal, and 6 an aberrant signal; 4 were negative; Table 3). An example is shown in Figure 3c,d, embryo 4. Such a discrepancy between activity of Oct4–GFP and Oct4 was never observed in controls.

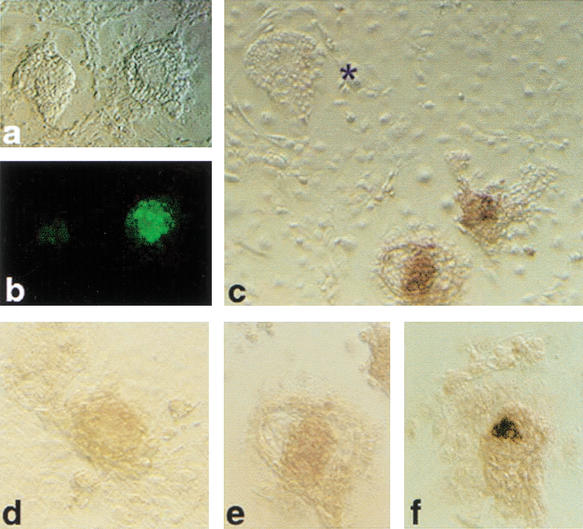

Outgrowth formation and presence of a pluripotent cell population in cloned blastocysts

The abnormalities in Oct4 expression in clones suggest that pluripotency is compromised in a large proportion of cloned blastocysts. This is difficult to verify by subsequent transfer in vivo because of large periimplantation losses precluding efficient recovery of material. We therefore used outgrowth formation as an in vitro model for implantation and immediate postimplantation development. Cumulus cell-derived clones at 96 h of development were placed on feeder layers to support outgrowth formation. Compared with controls (IVF), clones were limited in their ability to form outgrowths (Table 4). Furthermore, half (52%) of all clone outgrowths lacked Oct4-mRNA-expressing cells (Table 4; Fig. 5c), indicating defects in lineage formation. In clone outgrowths with Oct4-expressing cells, levels of Oct4 mRNA were generally lower (Fig. 5d,e) than in controls (Fig. 5f). Several clone morulae (13) that failed to cavitate attached and formed outgrowths; however, all (n = 7) that were analyzed by in situ hybridization lacked Oct4 expression. In contrast to somatic cell clones, all 43 germ-cell-derived clones were able to attach and outgrow and contained Oct4–GFP-expressing cells.

Table 4.

Expression of Oct4 in outgrowths from clone and control embryos

|

|

Morulae on feeders n

|

Outgrowths formed n

|

Outgrowths analyzed n

|

Oct4 mRNA signal

|

Replicates n

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| absent

|

present

|

|||||||

|

n (%)

| ||||||||

| Cumulus cell clones | 143 | 55 | 29a | 15 (52) | 14 (42) | 6 | ||

| IVF embryos | 140 | 115 | 115 | 0 (0) | 115 (100) | 5 | ||

Fisher exact test on the Oct4 mRNA signal: P < 0.001.

A total of 26 of 55 clones were analyzed for expression of other genes for which data were inconclusive.

Figure 5.

Outgrowths from cumulus cell clones after 3 d of culture on a feeder layer. (a) Bright field; (b) Oct4–GFP fluorescence on same outgrowths as in a; (c) in situ hybridization for Oct4 mRNA on synchronous clone outgrowths; (*) outgrowth lacking Oct4 mRNA-expressing cells. (d,e) Clone outgrowths and (f) outgrowth from fertilized blastocyst illustrating level of Oct4 expression detected after 2 h of color reaction.

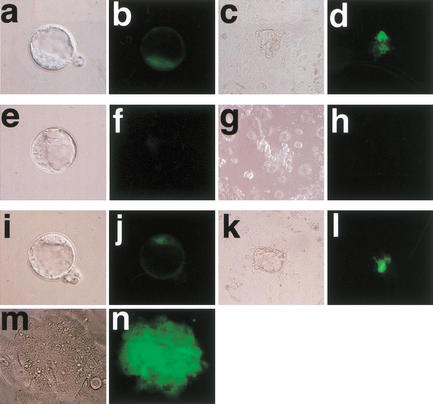

To determine whether the Oct4–GFP signal within the blastocyst-stage clone related to subsequent development, Oct4–GFP was graded in blastocysts as being either absent, weak, or strong (according to a relative scale of intensity; Fig. 6). The blastocysts were placed on a feeder layer and assessed for outgrowth formation. Clones with strong Oct4–GFP had a higher probability of forming outgrowths than did those with weak or absent signal (Fig. 6). In most cases, a strong GFP signal in the blastocyst corresponded to a strong signal in the outgrowths. The potential of outgrowths to develop further was tested by determining whether they could form ES cells. ES cell line derivation was only achieved from outgrowths with strong GFP (3/13), but not from outgrowths with weak or absent GFP (0/15; Figs. 6 and 7).

Figure 6.

Oct4–GFP level in clone blastocysts and outgrowth formation.

Figure 7.

Oct4–GFP in blastocyst-stage clones, outgrowths, and ES cells. (a–d) Fertilized embryo and (e–l) clones at the blastocyst stage and their subsequent outgrowth; (m,n) ES cell formation from the last embryo illustrated in i–l including corresponding GFP signals. The clone in e and f is almost negative for GFP, and shows no GFP in the outgrowths. The clone in i and j has GFP comparable to the control and shows GFP-positive cells in both ICM and outgrowth, and formed ES cells.

Discussion

In this study, we show that cloned mouse blastocysts seldom show Oct4 spatial distribution and gene activity compatible with normal embryonic development. Previous studies have shown that development beyond the blastocyst stage depends on Oct4 (Nichols et al. 1998), and the Oct4 level determines the fate of embryonic stem cells in vitro (Niwa et al. 2000). Analysis of the immediate postimplantation period, using an in vitro outgrowth model, was used to correlate development and Oct4 expression. We showed that if the inner cell mass of cloned blastocysts has inappropriate levels of Oct4, the capacity of these cells to form embryonic lineages is reduced. Strikingly, the frequency of abnormal Oct4 expression patterns in blastocyst-stage mouse clones alone can account for the low rates of postimplantation survival of clones. This is supported by the observation that Oct4–GFP signal in blastocysts correlates with subsequent outgrowth formation, Oct4–GFP in outgrowths, and the ability to form ES cells. These data suggest that Oct4 is either preferentially subject to reprogramming errors and/or reflects reprogramming failures of other genes.

The postimplantation development of clones (Table 1) indicates that most clones that develop to the morula and blastocyst stages have limited developmental potential. Usually, blastocyst formation is an indicator of development proceeding normally. However, blastocysts can also be formed in the absence of essential genes or in embryos with abnormal imprinting, as is the case for several null mutants (Fässler and Meyer 1995; Feldman et al. 1995; Stephens et al. 1995; Chawengsaksophak et al. 1997; Nichols et al. 1998) as well as tetraploid, androgenetic, and parthenogenetic embryos, all of which fail after implantation. Absence of Oct4 is known to be compatible with formation of blastocyst-like structures. However, cells located in the inner cell mass of Oct4−/− blastocysts have an altered cell fate, precluding subsequent development. This highlights the importance of molecular markers to identify true blastocysts. Expression patterns of Oct4 in blastocyst-stage somatic cell clones, as seen by in situ analysis, predict limitations in, or preclusion of, subsequent development. The effect of aberrations in Oct4 levels in live blastocysts has been analyzed by generating Oct4-deficient embryos and ES cells. In both, low Oct4 levels resulted in differentiation into trophectoderm (Nichols et al. 1998; Niwa et al. 2000). Assuming a similar effect in clones, this would lead to an alteration in the potency of ICM cells and lineages arising thereof. This was consistent with the observation that 11% of blastocyst-stage clones lacked Oct4, and that with abnormal expression in the majority at the blastocyst stage, half of the outgrowths derived from these clones lacked Oct4-expressing cells. Furthermore, blastocysts and outgrowths with low or absent Oct4–GFP did not give rise to ES cells.

Somatic and embryonic cell cloning experiments have shown that, compared with the metaphase II ooplasm, the zygotic cytoplasm is an inadequate host to the transplanted nucleus (McGrath and Solter 1984; Robl et al. 1986; Willadsen 1986; Howlett et al. 1987; Cheong et al. 1993, 1994). It is generally assumed that reprogramming subsequent to activation is minor; therefore, much effort to improve clone development has focused on the metaphase II ooplasm (Sun and Moor 1995; DiBerardino 1997; for review, see Solter 2000). However, reprogramming of transplanted nuclei is not totally restricted to the metaphase II oocyte, as somatic cell nuclei reconstituted with a zygotic cytoplasm, although not viable, can undergo some extent of preimplantation development (McGrath and Solter 1984; Wakayama et al. 2000). If reprogramming after nuclear transfer continues during cleavage, it would extend the period during which factors could influence reprogramming of the nucleus. An extended window of reprogramming would also facilitate increased variability in gene function between clones but also between cells of the same clone. In this study, we observed features in Oct4 and Oct4–GFP expression consistent with this hypothesis. Blastocyst-stage clones had a mosaic pattern of Oct4, suggesting a stable reprogramming event in some cells but not others, which could be owing to reprogramming influences subsequent to the four- to eight-cell stage.

The Oct4 gene is temporally and spatially regulated throughout development (Pesce et al. 1998). Zygotic Oct4 expression starts at the four- to eight-cell stage. Zygotic expression is the first event to test reprogramming from a somatic cell nucleus. In our studies, regardless of the origin of the nucleus, somatic or germ cell, the time of onset of Oct4–GFP signal was the same as in normal embryos. The correct temporal onset of Oct4–GFP expression in the majority of clones contrasts with correct distribution of Oct4 in only a minority of blastocyst-stage clones. Thus, whereas Oct4 activation appears to be normal, maintenance of expression and cell-type-specific Oct4 regulation in the first two lineages established in the embryo (TE, ICM) is not. Activation of Oct4 is unlikely to be attributable to a general opening of chromatin after nuclear transfer. If this were the case, we would have expected CD8–GFP to be activated as well. However, in agreement with CD8–GFP not being expressed during preimplantation stages, the transgene was not activated in clones at any preimplantation stage. As shown by the induction of transgene activity by TSA treatment, transcription factors required for CD8 activation are present in the early embryo. Therefore, factor accessibility appears to be different for both genes, suggesting at least some degree of specificity in the process of gene reprogramming at the four- to eight-cell stage. The fact that gene activation is normal but gene regulation in subsequent stages is not, may suggest that different processes are involved in reprogramming in early- versus later-stage clones. In particular, factors in the oocyte cytoplasm may be responsible for gene-specific expression at the four-cell stage, whereas regulation at later stages is likely to require the presence of newly expressed proteins.

Inadequate maintenance of Oct4 expression reflects improper regulation. Transcription factors that were initially present in the oocyte may not have been resynthesized, or factors that normally repress Oct4 in the TE might have been expressed in the ICM. Alternatively, the process of chromatin remodeling might be dysfunctional, thus randomly silencing Oct4 or the Oct4–GFP transgene. However, comparison of the endogenous Oct4 and Oct4–GFP shows that in rare cases, only one is active within the same cell. Thus, absence of activators or presence of repressors cannot be the reason in both cases.

Abnormal pattern of Oct4 expression and Oct4–GFP in somatic cell mouse clones suggests that developmental competence of clones is already compromised at the blastocyst stage and reflected in subsequent development. Defects in the expression of other genes besides Oct4 would compound the extent of developmental failure and could explain why many clones with correct Oct4 expression fail, as evident from the low number of fetuses developing. Our results with cloning from germ cells show that a high proportion of clones that developed to the blastocyst stage and had normal Oct4–GFP levels, nonetheless failed at a dramatic rate postimplantation. This shows that there are considerable additional requirements that need to be fulfilled, other than reprogramming of Oct4, that do not obviously affect preimplantation development. Therefore, it would be interesting to examine other genes essential for periimplantation development for both the level of expression and spatial distribution. This could include genes that have been previously found, by RT-PCR analysis but not spatial distribution, to be similar to controls (Daniels et al. 2000, 2001; Wrenzycki et al. 2001).

Besides reprogramming, other factors may be involved in the poor development of clones both during preimplantation and postimplantation development, including effects of micromanipulation, oocyte activation, and in vitro culture. As seen for development of ICSI and IVF control embryos compared with somatic cell clones, these factors most likely contribute in part. In contrast, clones reconstituted from Oct4–GFP-positive fetal germ-cell nuclei developed and showed Oct4–GFP similarly to controls despite identical treatment to somatic cell clones. Therefore, features specific to the somatic nature of the donor nucleus are implicit to poor development. The superior development of germ cell clones during preimplantation development and implantation compared with somatic cell clones does not necessarily indicate a higher degree of reprogramming. Different cell types show different rates of success in cloning that could reflect more or less compatibility of the somatic cell genome with a preimplantation-stage embryo (Wakayama et al. 1999; Wakayama and Yanagimachi 1999a, 2001; Ogura et al. 2000a,b). A particularly good example consistent with this hypothesis is that of ES-cell-derived clones, which show extremely poor development until clones develop to the stage at which ES cells are derived (Wakayama et al. 1999; Rideout et al. 2000; Amano et al. 2001; Humpherys et al. 2001).

Consequences of disturbances in gene expression, epigenetic state, or chromatin structure may be obvious only in the adult organism. A well-known problem of cloning is that mice often develop obesity (Tamashiro et al. 2000). A recent report shows that this phenotype is not transmitted to their offspring, even if two obese parents are mated (Tamashiro et al. 2002). This shows that an epigenetic disturbance that had been introduced by the cloning procedure has an apparent effect only much later in the adult. Furthermore, this epigenetic disturbance can be corrected or reset during gametogenesis. Understanding how the perturbances in Oct4 expression in clones are or can be normalized is likely to enhance further developmental success and may also reduce the long-term effects in the adult. However, although such studies may help to reduce epigenetic problems, we foresee that it will not be possible to exclude genetic problems such as the presence of somatic DNA mutations in the nuclei used for cloning. As many examples show, one single point mutation may have a detrimental impact on the embryo or in the adult.

Materials and methods

Reagents

All reagents were purchased from Sigma unless stated otherwise.

Mice

Mice were purchased from Taconic (C57Bl/6J X C3H/HeN, referred to as B6C3) or Charles River (albino ICR). Oct4–GFP homozygous transgenic mice (OG2), described previously (Yoshimizu et al. 1999; Szabo et al. 2002), were kindly provided by J.R. Mann (Beckman Research Institute of the City of Hope, Duarte, CA). Female B6C3 mice, four- to six-week-old, were superovulated with 7.5 U of pregnant mare's serum gonadotropin (PMSG), followed by 7.5 U of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) 48 h later, to provide the recipient oocytes for nuclear transfer. The nucleus-donor cells were obtained from ICR × OG2 mice (OG2F1) and were therefore Oct4–GFP+/−. Female ICR mice were used as recipients for embryo transfer. Animals were maintained and used for experimentation according to the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Pennsylvania.

Recipient oocytes for nuclear transfer

Ovulated cumulus–oocyte complexes were collected 14 h after hCG injection of PMSG-primed B6C3 females. Cumulus cells were removed by hyaluronidase treatment (50 U/mL in HEPES-buffered CZB medium at 20°C). Cumulus-free oocytes were washed free of hyaluronidase and incubated in M16 medium (see Embryo Culture).

Nucleus-donor cells

Oct4–GFP transgenic donor cells were used to visualize (re-) expression of the transgene after nuclear transfer. Adult cumulus cells were isolated from the cumulus–oocyte complexes ovulated by OG2F1 females as described above. Fetal germ cells were mechanically isolated from the gonads of 13.5–16.5-dpc OG2F1 male fetuses and used within 3 h. The identity of germ cells was ascertained by morphology and Oct4–GFP expression, germ cells being the only GFP-positive cells after gastrulation (Yoshimizu et al. 1999). Mouse embryonic fibroblasts carrying the CD8–GFP transgene (unknown genomic background) were obtained from U. von Andrian (The Center for Blood Research, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA). The nucleus-donor cells were washed in HEPES-CZB medium, centrifuged, and suspended in the micromanipulation medium (see below).

Microsurgery and activation of reconstructed oocytes

Removal of metaphase chromosomes (enucleation) and nuclear transfer were carried out as described (Wakayama et al. 1998) with the following modifications: Recipient oocytes and nucleus-donor cells were handled in modified HEPES-buffered CZB medium (BSA-free, PVP 1% w/v). Oocytes were processed in batches of 20 within a 10-min window at 28°C using piezo-driven (PMM 150 FU, PrimeTech) borosilicate needles and DIC optics (Nikon). After microsurgery, the nucleus-transplanted oocytes were incubated in M16 medium at 37°C; 2–3 h later, they were activated in modified (Ca-free, SrCl2 10 mM) M16 medium for 6 h in the presence of cytochalasin B (5 μg/mL, from a 200× stock solution in DMSO) to prevent polar body extrusion. The reconstructed oocytes were routinely scored for pronuclear formation, and two pronuclei were typically observed.

In vitro fertilization (IVF) and intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI)

Sperm was isolated by swim-up from the cauda epididymis of mature OG2 (Oct4+/+) males and allowed to capacitate in Whittingham medium (3% BSA, fraction V) for 1.5 h prior to oocyte insemination or injection. Fertilized oocytes were recovered from the insemination drop 2 h later. ICSI was performed by piezo-driven injection into oocytes of acrosome-reacted sperm heads without a tail (Kimura and Yanagimachi 1995). Polar body extrusion usually occurred within 2 (IVF) or 3 (ICSI) h. Zygotes and embryos were cultured in M16 medium as described above. These embryos provided the controls for blastocyst development, outgrowth formation, and in situ analysis.

Embryo culture

Cloned and fertilized embryos were cultured in groups of 50–100 in 30-μL drops of M16 medium in 35-mm dishes (Falcon 3001, Becton & Dickinson) covered with light mineral oil under 5% CO2 at 37°C. They were assessed at 72 and 96 h for the rate of morula and blastocyst formation, respectively, and for the presence of GFP activity.

Clones obtained from CD8–GFP nucleus-donor cells were treated with TSA at the four-cell stage, as described (Thompson et al. 1995). TSA is a histone deacetylase inhibitor that causes the nucleosomal structure of chromatin to relax, thereby facilitating transcription.

Embryonic outgrowths and ES cell derivation

Cloned embryos were collected at the morula (data shown in Table 4) or blastocyst stage (Figs. 6 and 7) and their zonae pellucidae removed by brief exposure to acidic Tyrode solution. The denuded embryos were placed on a feeder layer of mitomycin C-inactivated confluent STO cells in a 4-well plate (Nunc). Culture of STO cells and embryos (outgrowths) was in DMEM (Specialty Media SLM-220B: 4.5 g/L glucose supplemented with 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids, 2 mM L-glutamine, 0.5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 14% HyClone fetal bovine serum, 50 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin). Morulae underwent cavitation in 24 h, and blastocysts attached within 48 h. Subsequent outgrowth formation was defined by the observation of trophoblast cells spreading from the attached blastocyst.

For ES cell derivation, clones were collected at 96 h of development and cultured for 72 h on feeder layers to form outgrowths as described above. Outgrowths were disaggregated by trypsinization and grown on feeder layers for 6 d. Subsequent passaging of ES colonies was performed as described by Abbondanzo et al. (1993).

Transfer of embryos in foster mothers

Two-cell-stage cloned and control embryos were transferred into the oviducts of pseudopregnant ICR females that had been mated with vasectomized ICR males and were used on the day of the copulation plug (0.5 dpc). Occasionally, morula-stage clones were transferred into the uteri of 2.5-dpc pseudopregnant ICR females. The females were monitored daily for weight increase. Those ascertained pregnant by significant weight increase were killed 10.5 dpc. Decidua were scored to determine the number of implantations. Cloned fetuses were genotyped from cells of the amniotic sac following the same procedure as described below.

Verification of transgene in GFP-negative clones

Blastocysts were prepared in 2 μL of lysis buffer (5 mM DTT, 0.8% Igepal CA630, 900 μg/mL proteinase K in milliQ water). Samples were heated at 65°C for 15 min and 94°C for 15 min prior to PCR. Two units of Taq Gold polymerase (Perkin Elmer–Applied Biosystems) was used per reaction volume (25 μL) in each of the two rounds of nested amplification. The thermal profile was as follows: Taq preactivation at 95°C for 12 min; 40 cycles at 94°C for 1 min, at 58°C for 1 min, and at 72°C for 2 min; final extension at 72°C for 10 min. Nested products (222 bp) were visualized by gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide staining. The primers for the first PCR were: GOF18-1, 5′-CAA AGA CCC CAA CGA GAA GC-3′; GOF18-2, 5′-GTC AAG AAG GCG ATA GAA GG-3′; for the second PCR: GOF18-3, 5′-GGC GCC CGG TTC TTT TTG TC-3′; GOF18-4, 5′-CCA TGA TGG ATA CTT TCT CG-3′. IVF transgenic (B6C3F1 × OG2) and wild-type (B6C3) blastocysts were used as positive and negative controls, respectively.

Whole-mount in situ hybridization (ISH) of mouse embryos and outgrowths

Digoxigenin-labeled riboprobes (Oct4 cDNA, sense and antisense) were generated by T3 and T7 polymerases from linearized pBluescript containing a full-length Oct4 cDNA insert (Schöler et al. 1990) using Dig-labeling components (Roche Bioscience), according to the manufacturer's protocol. Control and cloned embryos were cultured to the blastocyst stage. Embryos and outgrowths were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde/0.1% glutaraldehyde at room temperature for 30 min. ISH was performed as described (Oblin and Clarke 1997), with the following modifications. Hybridization was at 58°C overnight, in 5× SSC (pH 5), 50% formamide, 50 μg/mL heparin, 0.1% Tween-20, 100μg/mL tRNA, and 100 μg/mL denatured sheared salmon sperm DNA. Posthybridization washes were in 2× SSC (pH 4.5), 50% formamide, 0.1% Tween-20, twice at room temperature and three times at 59°C for 30 min each. Embryos were mounted in microdrops and positioned to localize the ICM.

Statistical analysis

Proportions were compared by a simple two-tailed z test not requiring the square root and arc sin transformation. Counts were analyzed in cross tabs through χ2 and the Fisher's exact test. Tests were performed as described (Glantz 1992).

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Marianne Friez for technical assistance. We thank J.R. Mann (Division of Biology, Beckman Research Institute of the City of Hope, Duarte, CA) for providing the OG2 mouse strain, and U.H. von Andrian (The Center for Blood Research, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA) for supplying the CD8–GFP mouse fibroblasts. We also thank Fatima Cavaleri, James Kehler, Katharina Lins, and Alexey Tomilin for critical suggestions. We thank Areti Malapetsa for editing the manuscript. This work was supported by the Marion Dilley and David George Jones Funds and the Commonwealth and General Assembly of Pennsylvania.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL scholer@vet.upenn.edu; FAX (610) 925-8121.

Article and publication are at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.966002.

References

- Abbondanzo SJ, Gadi I, Stewart CL. Derivation of embryonic stem cell lines. Methods Enzymol. 1993;225:803–823. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(93)25052-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amano T, Tani T, Kato Y, Tsunoda Y. Mouse cloned from embryonic stem (ES) cells synchronized in metaphase with nocodazole. J Exp Zool. 2001;289:139–145. doi: 10.1002/1097-010x(20010201)289:2<139::aid-jez7>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botquin V, Hess H, Fuhrmann G, Anastassiadis C, Gross MK, Vriend G, Schöler HR. New POU dimer configuration mediates antagonistic control of an osteopontin preimplantation enhancer by Oct-4 and Sox-2. Genes & Dev. 1998;12:2073–2090. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.13.2073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chawengsaksophak K, James R, Hammond VE, Kontgen F, Beck F. Homeosis and intestinal tumours in Cdx2 mutant mice. Nature. 1997;386:84–87. doi: 10.1038/386084a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheong HT, Takahashi Y, Kanagawa H. Birth of mice after transplantation of early cell-cycle-stage embryonic nuclei into enucleated oocytes. Biol Reprod. 1993;48:958–963. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod48.5.958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheong HT, Takahashi Y, Kanagawa H. Relationship between nuclear remodeling and subsequent development of mouse embryonic nuclei transferred to enucleated oocytes. Mol Reprod Dev. 1994;37:138–145. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1080370204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collas P, Robl JM. Relationship between nuclear remodeling and development in nuclear transplant rabbit embryos. Biol Reprod. 1991;45:455–465. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod45.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czolowska R, Modlinski JA, Tarkowski AK. Behaviour of thymocyte nuclei in non-activated and activated mouse oocytes. J Cell Sci. 1984;69:19–34. doi: 10.1242/jcs.69.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dailey L, Yuan H, Basilico C. Interaction between a novel F9-specific factor and octamer-binding proteins is required for cell-type-restricted activity of the fibroblast growth factor 4 enhancer. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:7758–7769. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.12.7758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels R, Hall V, Trounson AO. Analysis of gene transcription in bovine nuclear transfer embryos reconstructed with granulosa cell nuclei. Biol Reprod. 2000;63:1034–1040. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod63.4.1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels R, Hall VJ, French AJ, Korfiatis NA, Trounson AO. Comparison of gene transcription in cloned bovine embryos produced by different nuclear transfer techniques. Mol Reprod Dev. 2001;60:281–288. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiBerardino MA. Genomic potential of differentiated cells. New York, NY: Columbia University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Du Z, Cong H, Yao Z. Identification of putative downstream genes of Oct-4 by suppression–subtractive hybridization. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;282:701–706. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggan K, Akutsu H, Hochedlinger K, Rideout W, Yanagimachi R, Jaenisch R. X-Chromosome inactivation in cloned mouse embryos. Science. 2000;290:1578–1581. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5496.1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezashi T, Ghosh D, Roberts RM. Repression of Ets-2-induced transactivation of the τ interferon promoter by Oct-4. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:7883–7891. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.23.7883-7891.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fässler R, Meyer M. Consequences of lack of β 1 integrin gene expression in mice. Genes & Dev. 1995;9:1896–1908. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.15.1896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman B, Poueymirou W, Papaioannou VE, DeChiara TM, Goldfarb M. Requirement of FGF-4 for postimplantation mouse development. Science. 1995;267:246–249. doi: 10.1126/science.7809630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glantz SA. Primer of biostatistics. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Howlett SK, Barton SC, Surani MA. Nuclear cytoplasmic interactions following nuclear transplantation in mouse embryos. Development. 1987;101:915–923. doi: 10.1242/dev.101.4.915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humpherys D, Eggan K, Akutsu H, Hochedlinger K, Rideout WM, III, Biniszkiewicz D, Yanagimachi R, Jaenisch R. Epigenetic instability in ES cells and cloned mice. Science. 2001;293:95–97. doi: 10.1126/science.1061402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue K, Kohda T, Lee J, Ogonuki N, Mochida K, Noguchi Y, Tanemura K, Kaneko-Ishino T, Ishino F, Ogura A. Faithful expression of imprinted genes in cloned mice. Science. 2002;295:297. doi: 10.1126/science.295.5553.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanka J, Fulka J, Jr, Fulka J, Petr J. Nuclear transplantation in bovine embryo: Fine structural and autoradiographic studies. Mol Reprod Dev. 1991;29:110–116. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1080290204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanka J, Hozak P, Heyman Y, Chesne P, Degrolard J, Renard JP, Flechon JE. Transcriptional activity and nucleolar ultrastructure of embryonic rabbit nuclei after transplantation to enucleated oocytes. Mol Reprod Dev. 1996;43:135–144. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(199602)43:2<135::AID-MRD1>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura Y, Yanagimachi R. Intracytoplasmic sperm injection in the mouse. Biol Reprod. 1995;52:709–720. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod52.4.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishikawa H, Wakayama T, Yanagimachi R. Comparison of oocyte-activating agents for mouse cloning. Cloning. 1999;1:153–159. doi: 10.1089/15204559950019915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo DB, Kang YK, Choi YH, Park JS, Kim HN, Kim T, Lee KK, Han YM. Developmental potential and transgene expression of porcine nuclear transfer embryos using somatic cells. Mol Reprod Dev. 2001;58:15–21. doi: 10.1002/1098-2795(200101)58:1<15::AID-MRD3>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavoir MC, Kelk D, Rumph N, Barnes F, Betteridge KJ, King WA. Transcription and translation in bovine nuclear transfer embryos. Biol Reprod. 1997;57:204–213. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod57.1.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manjunath N, Shankar P, Stockton B, Dubey PD, Lieberman J, von Andrian UH. A transgenic mouse model to analyze CD8+ effector T cell differentiation in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1999;96:13932–13937. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.13932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath J, Solter D. Inability of mouse blastomere nuclei transferred to enucleated zygotes to support development in vitro. Science. 1984;226:1317–1319. doi: 10.1126/science.6542249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols J, Zevnik B, Anastassiadis K, Niwa H, Klewe-Nebenius D, Chambers I, Schöler H, Smith A. Formation of pluripotent stem cells in the mammalian embryo depends on the POU transcription factor Oct4. Cell. 1998;95:379–391. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81769-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa H, Miyazaki J, Smith AG. Quantitative expression of Oct-3/4 defines differentiation, dedifferentiation or self-renewal of ES cells. Nat Genet. 2000;24:372–376. doi: 10.1038/74199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oblin C, Clarke HJ. Rapid whole-mount in situ hybridization protocol for mammalian oocytes and preimplantation embryos. Elsevier Trends Journals Tech Tips Online TTO. 1997;1:5. [Google Scholar]

- Ogura A, Inoue K, Ogonuki N, Noguchi A, Takano K, Nagano R, Suzuki O, Lee J, Ishino F, Matsuda J. Production of male cloned mice from fresh, cultured, and cryopreserved immature Sertoli cells. Biol Reprod. 2000a;62:1579–1584. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod62.6.1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogura A, Inoue K, Takano K, Wakayama T, Yanagimachi R. Birth of mice after nuclear transfer by electrofusion using tail tip cells. Mol Reprod Dev. 2000b;57:55–59. doi: 10.1002/1098-2795(200009)57:1<55::AID-MRD8>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohgane J, Wakayama T, Kogo Y, Senda S, Hattori N, Tanaka S, Yanagimachi R, Shiota K. DNA methylation variation in cloned mice. Genesis. 2001;30:45–50. doi: 10.1002/gene.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ovitt CE, Schöler HR. The molecular biology of Oct-4 in the early mouse embryo. Mol Hum Reprod. 1998;4:1021–1031. doi: 10.1093/molehr/4.11.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmieri SL, Peter W, Hess H, Schöler HR. Oct-4 transcription factor is differentially expressed in the mouse embryo during establishment of the first two extraembryonic cell lineages involved in implantation. Dev Biol. 1994;166:259–267. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesce M, Schöler HR. Oct-4: Gatekeeper in the beginnings of mammalian development. Stem Cells. 2001;19:271–278. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.19-4-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesce M, Gross MK, Schöler HR. In line with our ancestors: Oct-4 and the mammalian germ. Bioessays. 1998;20:722–732. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199809)20:9<722::AID-BIES5>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prather RS, Sims MM, First NL. Nuclear transplantation in early pig embryos. Biol Reprod. 1989;41:414–418. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod41.3.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rideout WM, Wakayama T, Wutz A, Eggan K, Jackson-Grusby L, Dausman J, Yanagimachi R, Jaenisch R. Generation of mice from wild-type and targeted ES cells by nuclear cloning. Nat Genet. 2000;24:109–110. doi: 10.1038/72753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robl JM, Gilligan B, Critser ES, First NL. Nuclear transplantation in mouse embryos: Assessment of recipient cell stage. Biol Reprod. 1986;34:733–739. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod34.4.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schöler HR, Ruppert S, Suzuki N, Chowdhury K, Gruss P. New type of POU domain in germ line-specific protein Oct-4. Nature. 1990;344:435–439. doi: 10.1038/344435a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz GA, Harvey MB, Watson AJ, Arcellana-Panilio MY, Jones K, Westhusin ME. Regulation of early embryonic development by growth factors: Growth factor gene expression in cloned bovine embryos. J Animal Sci. 1996;75:50–57. [Google Scholar]

- Smith SD, Soloy E, Kanka J, Holm P, Callesen H. Influence of recipient cytoplasm cell stage on transcription in bovine nucleus transfer embryos. Mol Reprod Dev. 1996;45:444–450. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(199612)45:4<444::AID-MRD6>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solter D. Mammalian cloning: Advances and limitations. Nat Rev. 2000;1:199–207. doi: 10.1038/35042066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens LE, Sutherland AE, Klimanskaya IV, Andrieux A, Meneses J, Pedersen RA, Damsky CH. Deletion of β 1 integrins in mice results in inner cell mass failure and peri-implantation lethality. Genes & Dev. 1995;9:1883–1895. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.15.1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice SL, Robl JM. Nuclear reprogramming in nuclear transplant rabbit embryos. Biol Reprod. 1988;39:657–664. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod39.3.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun FZ, Moor RM. Nuclear transplantation in mammalian eggs and embryos. Curr Top Dev Biol. 1995;30:147–176. doi: 10.1016/s0070-2153(08)60566-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabó, P.E., Hübner, K., Schöler, H., and Mann, J.R. 2002. Allele specific expression of imprinted genes in mouse migratory primordial germ cells. Mech. Dev. (in press). [DOI] [PubMed]

- Tamashiro KL, Wakayama T, Blanchard RJ, Blanchard DC, Yanagimachi R. Postnatal growth and behavioral development of mice cloned from adult cumulus cells. Biol Reprod. 2000;63:328–334. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod63.1.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamashiro KLK, Wakayama T, Akutsu H, Yamazaki Y, Lachey JL, Wortman MD, Seeley RJ, D'Alessio DA, Woods SC, Yanagimachi R, et al. Cloned mice have an obese phenotype not transmitted to their offspring. Nat Med. 2002;8:262–264. doi: 10.1038/nm0302-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson EM, Adenot P, Tsuji FI, Renard JP. Real time imaging of transcriptional activity in live mouse preimplantation embryos using a secreted luciferase. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1995;92:1317–1321. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Stekelenburg-Hamers AE, Rebel HG, van Inzen WG, de Loos FA, Drost M, Mummery CL, Weima SM, Trounson AO. Stage-specific appearance of the mouse antigen TEC-3 in normal and nuclear transfer bovine embryos: Re-expression after nuclear transfer. Mol Reprod Dev. 1994;37:27–33. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1080370105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakayama T, Yanagimachi R. Cloning of male mice from adult tail-tip cells. Nat Genet. 1999a;22:127–128. doi: 10.1038/9632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— Cloning the laboratory mouse. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 1999b;10:253–258. doi: 10.1006/scdb.1998.0267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— Mouse cloning with nucleus donor cells of different age and type. Mol Reprod Dev. 2001;58:376–383. doi: 10.1002/1098-2795(20010401)58:4<376::AID-MRD4>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakayama T, Perry AC, Zuccotti M, Johnson KR, Yanagimachi R. Full-term development of mice from enucleated oocytes injected with cumulus cell nuclei. Nature. 1998;394:369–374. doi: 10.1038/28615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakayama T, Rodriguez I, Perry AC, Yanagimachi R, Mombaerts P. Mice cloned from embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1999;96:14984–14989. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.14984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakayama T, Tateno H, Mombaerts P, Yanagimachi R. Nuclear transfer into mouse zygotes. Nat Genet. 2000;24:108–109. doi: 10.1038/72749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willadsen SM. Nuclear transplantation in sheep embryos. Nature. 1986;320:63–65. doi: 10.1038/320063a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winger QA, Hill JR, Shin T, Watson AJ, Kraemer DC, Westhusin ME. Genetic reprogramming of lactate dehydrogenase, citrate synthase, and phosphofructokinase mRNA in bovine nuclear transfer embryos produced using bovine fibroblast cell nuclei. Mol Reprod Dev. 2000;56:458–464. doi: 10.1002/1098-2795(200008)56:4<458::AID-MRD3>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrenzycki C, Wells D, Herrmann D, Miller A, Oliver J, Tervit R, Niemann H. Nuclear transfer protocol affects messenger RNA expression patterns in cloned bovine blastocysts. Biol Reprod. 2001;65:309–317. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod65.1.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrenzycki C, Lucas-Hahn A, Herrmann D, Lemme E, Korsawe K, Niemann H. In vitro production and nuclear transfer affect dosage compensation of the X-linked gene transcripts G6PD, PGK, and Xist in preimplantation bovine embryos. Biol Reprod. 2002;66:127–134. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod66.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeom YI, Fuhrmann G, Ovitt CE, Brehm A, Ohbo K, Gross M, Hubner K, Schöler HR. Germline regulatory element of Oct-4 specific for the totipotent cycle of embryonal cells. Development. 1996;122:881–894. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.3.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimizu T, Sugiyama N, De Felice M, Yeom YI, Ohbo K, Masuko K, Obinata M, Abe K, Schöler HR, Matsui Y. Germline-specific expression of the Oct-4/green fluorescent protein (GFP) transgene in mice. Dev Growth Differ. 1999;41:675–684. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-169x.1999.00474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan H, Corbi N, Basilico C, Dailey L. Developmental-specific activity of the FGF-4 enhancer requires the synergistic action of Sox2 and Oct-3. Genes & Dev. 1995;9:2635–2645. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.21.2635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]