Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Limited data suggest that psychological factors, including binge eating, dieting, and depressive symptoms, may predispose children to excessive weight gain. We investigated the relationship between baseline psychological measures and changes in body fat (measured with dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry) over time among children thought to be at high risk for adult obesity.

METHODS

A cohort study of a convenience sample of children (age: 6–12 years) recruited from Washington, DC, and its suburbs was performed. Subjects were selected to be at increased risk for adult obesity, either because they were overweight when first examined or because their parents were overweight. Children completed questionnaires at baseline that assessed dieting, binge eating, disordered eating attitudes, and depressive symptoms; they underwent measurements of body fat mass at baseline and annually for an average of 4.2 years (SD: 1.8 years).

RESULTS

Five hundred sixty-eight measurements were obtained between July 1996 and December 2004, for 146 children. Both binge eating and dieting predicted increases in body fat. Neither depressive symptoms nor disturbed eating attitudes served as significant predictors. Children who reported binge eating gained, on average, 15% more fat mass, compared with children who did not report binge eating.

CONCLUSIONS

Children’s reports of binge eating and dieting were salient predictors of gains in fat mass during middle childhood among children at high risk for adult obesity. Interventions targeting disordered eating behaviors may be useful in preventing excessive fat gain in this high-risk group.

Keywords: child, disturbed eating behaviors, depression, adiposity, overweight

Strong predictors of adult obesity include having overweight parents and having been overweight during middle childhood.1 However, the specific mechanisms promoting weight gain for such children remain unclear. Among the genetic and environmental factors that underlie the propensity to gain weight, behavioral and psychological phenotypes are important potential targets because they may be amenable to modification.

Limited prospective data support the importance of depressive symptoms and self-reported dieting and binge eating for development of overweight. Some,2–5 but not all,6,7 longitudinal studies found major depression or depressive symptoms to be predisposing factors for later weight gain among children and adolescents. Self-reported dieting5,8,9 and binge eating8,9 were found to be associated with gains in self-reported BMI9,10 and measured BMI5,8 among preadolescents and adolescents. However, no study examined variables of disturbed eating patterns in combination with depressive symptoms among young children at high risk for adult obesity. Furthermore, no prior study examined body fat mass to investigate how these psychological factors affect gain of adipose tissue rather than gain of total body mass. Therefore, we assessed prospectively the relationships of children’s self-reported binge eating and dieting behaviors, depressive symptoms, and disordered eating attitudes to increases in body fat mass among children thought to be at high risk for adult obesity. We hypothesized that each psychological variable at baseline would contribute significantly to fat mass gain.

METHODS

Subjects

Children thought to be at increased risk (beyond shared environmental risk) for adult obesity were recruited through mailed notices to parents of 6- to 12-year-old black and white children in 3 Maryland school districts and through physician referrals and advertisements in the Washington, DC, metropolitan area. Mailings requested participation of children who were overweight or had ≥1 overweight parent and were willing to undergo radiographic examinations and to participate in metabolic studies. Approximately 7% of families responded to the school mailings, and subjects recruited directly from these mailings constituted 88% of the subjects studied. Inclusion criteria required that all children be considered at increased risk for overweight in adulthood by virtue of their own overweight (BMI for age and gender of ≥95th percentile)11 or their parents’ overweight (BMI of >25 kg/m2). No study subject was undergoing weight loss treatment. All subjects also understood that they would not receive treatment as part of the study but would be compensated financially for their participation. Subjects were healthy and medication-free for ≥2 weeks before baseline evaluation. Children provided written assent and parents gave written consent for participation in the study. This study was approved by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development institutional review board.

From 482 responses to mailings, 200 subjects enrolled in the present study. On the basis of parent-reported heights and weights for children who did not enroll (n = 282), enrolled children had significantly higher BMI z scores12,13 (mean: 2.64; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.26 to 3.03; vs mean: 0.84; 95% CI: 0.63 to 1.06), were significantly older (mean: 8.5 years; 95% CI: 8.3 to 8.7 years; vs mean: 7.7 years; 95% CI: 7.5 to 7.9 years), and were more likely to be white (64.7% vs 36%). There were no differences in the proportions of boys between children enrolled (46.4%) and those not enrolled (42.4%). Of the 200 children enrolled, 146 children (6–12 years of age at baseline) for whom body fat mass data were collected at ≥1 follow-up visit were included in the present study. The 54 children who were excluded from the present analyses because they did not return for ≥1 follow-up visit were not significantly different from those included with respect to age (mean: 8.5 years vs 8.5 years), socioeconomic status score14 (median: 3 vs 3), BMI z score (mean: 1.5 vs 1.6), fat mass (mean: 17.0 vs 16.3 kg), gender (proportion of boys: 55.3% vs 46.4%), or race distribution (proportion white: 59.6% vs 64.7%).

Procedures

Subjects were seen for a baseline assessment, during which physical and psychological measurements were obtained, and then annually for physical assessments. Children underwent dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scans, in the pencil-beam (QDR-2000; Hologic, Bedford, MA) or fan-beam (QDR-4500A; Hologic) mode, for determination of body fat mass. Body fat measurements obtained in the pencil-beam or fan-beam mode are each correlated strongly with fat mass determined with criterion methods; however, compared with the pencil-beam mode, our fan-beam mode instrument underestimated body fat mass for children by ~2.47 kg.15 To rectify this discrepancy, we added 2.47 kg to all total body fat measurements generated by the DXA densitometer in the fan-beam mode. Each child’s height was measured 3 times, to the nearest millimeter, with a stadiometer (Holtain, Crymmych, Wales) that was calibrated to the nearest millimeter before each child’s height measurement. Each child’s weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg with a calibrated digital scale (Scale-Tronix, Wheaton, IL). Height and weight measurements were conducted after a 12-hour fast, and children were clothed but with shoes removed. Parents’ height and weight values were self-reported. Questionnaires completed by children at baseline included the following: (1) The Children’s Depression Inventory16–18 is a validated, 27-item, self-report, symptom-oriented scale designed for school-aged children and adolescents (age: 6–17 years); it was validated with samples including black and white children.17 The cutoff score for clinical depression (total score of 19, of a maximal score of 54) represents the 90th percentile for children.19 The total score represents the sum of depressive symptoms related to negative mood, interpersonal problems, ineffectiveness, an-hedonia, and negative self-esteem. (2) The Adolescent Health Habits Survey20 is a self-report measure that assesses the frequency of dieting with the following question: “How many weight-loss diets have you started in the past?” Children were categorized as those who reported never dieting and those who reported dieting ≥1 time. This measure was used successfully with a sample of black and white adolescents.20 (3) The Questionnaire on Eating and Weight Patterns, Adolescent Version,21 is a self-report measure based on the adult Questionnaire on Eating and Weight Patterns-Revised22 and is designed to identify children with bulimia nervosa or binge eating disorder, according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision.23 Responses allow subjects to be classified according to the frequency of their reported binge eating (eating a large amount of food while experiencing a sense of loss of control). Children were categorized as those who reported never binge eating and those who reported ≥1 episode of binge eating in the past 6 months. (4) The Children’s Version of the Eating Attitude Test (ChEAT)24 is a self-report questionnaire designed to assess food preoccupation, dieting patterns, eating attitudes, and concerns about weight among children as young as 8 years of age. A score ≥20 (74th percentile) identifies disturbed eaters.25 The ChEAT total score was used as a general measure of disturbed eating and weight-related attitudes, because it correlates26 with the global score of the Eating Disorder Examination27 adapted for children.28 The Questionnaire on Eating and Weight Patterns, Adolescent Version, and the ChEAT have been administered to black and white children as young as 6 years of age.26,29 Because several of the children in the present sample were younger than the ages for which these measures were validated, questionnaires were read aloud, by a research assistant, to subjects with limited reading proficiency.

Statistical Analyses

Originally this study was powered to allow examination of several metabolic and behavioral outcomes and was expected to have >80% power (with α = .05) for the outcomes examined if >130 subjects were studied longitudinally. In this data set, both the number and timing of repeated observations varied among children; therefore, the statistical design was highly unbalanced, as is typically the case in observational studies, especially when the period of observation is several years.30 We used a mixed model with fixed effects for the independent variables of interest and a random child effect. In addition, the error structure included serial correlation, with a power structure that allowed the correlation to depend on the time interval between repeated observations for the same child. This variance structure has proved to be appropriate in a wide range of applications.30 Model parameters were estimated with maximal likelihood and restricted maximal likelihood analyses, with SAS 9.0 software (SAS Institute,, Cary, NC). CIs were computed by using approximate t statistics. Residual analysis confirmed the need for logarithmic transformation of the DXA scores. Effects were illustrated with partial residual plots and adjusted (least-squares) means. In addition to the main effects of the independent variables, the original mixed model included interaction effects of gender with both race and time in the study. Because neither of these interactions was significant for DXA fat mass, the interactions were removed to simplify the presentation of the results. Results of the models with and without interactions were very similar. On the basis of longitudinal studies examining child growth patterns,31,32 we included age at baseline, gender, race, socioeconomic status, baseline fat mass, pubertal stage, and time in the study as covariates in our model. To consider the relative contributions of the psychological variables in predicting increases in fat mass, for each model we included covariates and the 4 variables of interest, ie, depressive symptoms, self-reported dieting, binge eating, and ChEAT total score. Dieting and binge eating were categorical variables, and the remaining variables were continuous.

RESULTS

Data collection began in July 1996, and the follow-up period ended in December 2004. Follow-up periods ranged from 0.10 years to 7.9 years (mean: 4.2 years; SD: 1.8 years). A total of 568 measurements were obtained for study subjects. Study children gained, on average, 5.9 pounds of fat mass and 15.9 pounds of body weight per year.

Baseline demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1. All subjects completed the Children’s Depression Inventory and ChEAT at their first visit and 141 completed the Adolescent Health Habits questionnaire. At baseline, 6 children scored at or above the cutoff score (≥19) for clinical depression. At baseline, most children reported never having attempted dieting, whereas 45 children reported having attempted dieting ≥1 time. A total of 134 children completed the Questionnaire on Eating and Weight Patterns, Adolescent Version. At baseline, 88 subjects reported never binge eating and 46 children reported binge eating ≥1 time in the past 6 months. Twenty-one children (15.7%) reported both attempted dieting and binge eating. Bivariate correlations between baseline psychological variables and baseline body fat mass are presented in Table 2.

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Study Sample (N = 146)

| Characteristics | 6–7 y | 8–9 y | 10–12 y |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of subjects | 48 | 63 | 35 |

| Age, y | 7.2 ± 0.6 | 9.0 ± 0.5 | 10.8 ± 0.7 |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Female | 23 (15.8) | 37 (25.3) | 18 (12.3) |

| Male | 25 (17.1) | 26 (17.8) | 17 (11.6) |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| Black | 14 (9.6) | 21 (14.4) | 13 (8.9) |

| White | 34 (23.3) | 42 (28.8) | 22 (15.1) |

| Socioeconomic status score,14 mediana | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 |

| Fat mass, kg | 11.4 ± 7.9 | 17.5 ± 9.9 | 23.9 ± 14.0 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 20.6 ± 5.7 | 23.3 ± 5.9 | 25.50 ± 7.2 |

| BMI, z scoreb | 1.3 ± 1.2 | 1.5 ± 1.0 | 1.5 ± 1.1 |

| Weight status according to percentile, n (%) | |||

| <85th | 20 (13.7) | 20 (13.7) | 11 (7.5) |

| ≥85th to <95th | 10 (6.8) | 8 (5.5) | 4 (2.7) |

| ≥95th | 18 (12.3) | 35 (24.0) | 20 (13.7) |

| Overweight parents (BMI of >25 kg/m2), n (%)c | |||

| Neither parent overweight | 3 (2.1) | 2 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| One parent overweight | 4 (2.7) | 7 (4.8) | 8 (5.5) |

| Both parents overweight | 41 (28.1) | 51 (34.9) | 27 (18.5) |

| Reported dieting, n (%)d | |||

| Never dieted | 35 (24.0) | 45 (30.8) | 21 (14.4) |

| ≥1 diet | 13 (8.9) | 18 (12.3) | 14 (9.6) |

| Reported binge eating, n (%)e | |||

| No binge eating in past 6 mo | 34 (23.3) | 42 (28.8) | 24 (16.4) |

| ≥1 episode of binge eating in past 6 mo | 14 (9.6) | 21 (14.4) | 11 (7.5) |

| Depressive symptoms scoref | 8.7 ± 6.9 | 7.8 ± 6.1 | 5.1 ± 4.2 |

| Disordered eating attitudes scoreg | 9.7 ± 8.7 | 9.5 ± 7.3 | 8.6 ± 5.2 |

Values are means ± SD unless otherwise indicated.

For socioeconomic status, higher numbers are indicative of lower social status (range: 1–5).

BMI z scores indicate BMI accounting for differences among growing children based on their age and gender.12,13

Data were unavailable for 3 adopted subjects (2.1%), all of whom were overweight at baseline.

For 5 children, the Adolescent Health Habits Survey was not completed; demographic data for these children are included in the “never dieted” category.

For 12 children, the Questionnaire on Eating and Weight Patterns was not completed; demographic data for these children are included in the “no binge eating” category.

Children’s Depression Inventory Total Scale scores may range from 0 to 54; a score of ≥19 is indicative of clinical depression.

ChEAT scores may range from 0 to 78; a score of ≥20 identifies disturbed versus nondisturbed eaters.

TABLE 2.

Bivariate Correlation Coefficients of Baseline Psychological Predictors and Baseline Body Fat Mass

| Variable | Summary Statistics

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dieting Attempts | Depressive Symptoms | ChEAT Score | Fat Mass | |

| Binge eating | 0.21a | 0.25b | 0.26b | 0.20a |

| Dieting attempts | 0.13 | 0.21a | 0.49b | |

| Depressive symptoms | 0.38b | 0.02 | ||

| ChEAT total | 0.26b | |||

N =146; binge eating, n =134; dieting attempts, n =141.

P <.05.

P <.01.

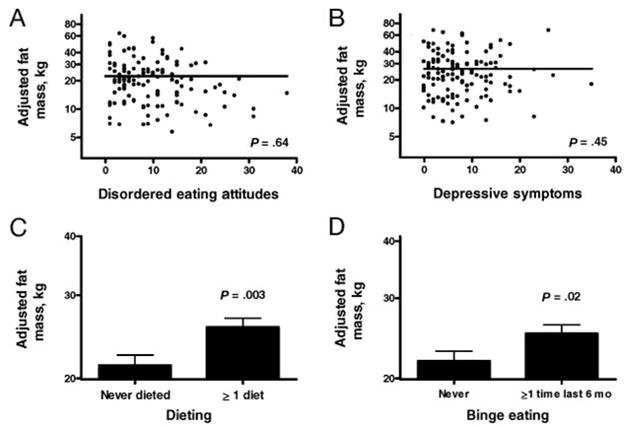

For the prediction of DXA fat mass, 134 subjects had complete baseline data. Taking into account correlations between yearly DXA fat mass measurements, the baseline fat mass (slope: 0.58; 95% CI: 0.48 to 0.68), years of follow-up assessment (slope: 0.11; 95% CI: 0.09 to 0.13), baseline dieting attempts (P = .003), and binge eating (P = .02), but neither depressive symptoms (slope: 0.004; 95% CI: −0.007 to 0.014) nor ChEAT total score (slope: 0.002; 95% CI: −0.007 to 0.011), were statistically significant predictors of increases in body fat mass (Fig 1). Table 3 provides the adjusted estimates based on all variables in the model. Children who reported dieting (point estimate: 0.19; 95% CI: 0.05 to 0.33) or binge eating in the past 6 months (point estimate: 0.14; 95% CI: 0.004 to 0.28) had significantly larger increases in fat mass than did those who did not report such behaviors. Children who reported binge eating gained, on average, an additional 15% more fat mass, compared with children with no binge eating.

FIGURE 1.

Associations between baseline psychological factors and changes in body fat mass over time. Fat mass values were logarithmically transformed for analysis. For disordered eating attitudes (A) and depressive symptoms (B), each subject’s partial residual was added to mean fat mass before retransformation to conventional units. For dieting attempts (C) and binge eating (D), retransformed least-squares means for fat mass are shown.

TABLE 3.

Mixed Regression Model for Predicting Increase in Body Fat Mass

| Predictor Variable | Adjusted β Coefficient in Model | SE | df | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female gender | 0.11 | 0.06 | 119 | −0.03 to 0.25 | .08 |

| Black race | 0.02 | 0.06 | 114 | −0.12 to 0.16 | .80 |

| Socioeconomic status | |||||

| 1 | 0.19 | 0.14 | 125 | −0.13 to 0.51 | .17 |

| 2 | −0.01 | 0.12 | 124 | −0.28 to 0.26 | .92 |

| 3 | 0.04 | 0.12 | 125 | −0.23 to 0.31 | .73 |

| 4 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 124 | −0.20 to 0.34 | .58 |

| Tanner pubertal stage | |||||

| 1 | 0.10 | 0.34 | 139 | −0.67 to 0.87 | .78 |

| 2 | 0.05 | 0.33 | 140 | −0.70 to 0.80 | .87 |

| 3 | −0.02 | 0.34 | 143 | −0.79 to 0.75 | .95 |

| Years of follow-up assessment | 0.11 | 0.01 | 372 | 0.09 to 0.13 | <.0001 |

| Age | 0.02 | 0.02 | 118 | −0.03 to 0.07 | .34 |

| Baseline body fat mass | 0.58 | 0.04 | 114 | 0.48 to 0.68 | <.0001 |

| Dieting attempts | 0.19 | 0.06 | 112 | 0.05 to 0.33 | .003 |

| Binge eating | 0.14 | 0.06 | 117 | 0.004 to 0.28 | .02 |

| ChEAT score | 0.002 | 0.004 | 115 | −0.007 to 0.011 | .64 |

| Depressive symptoms | 0.004 | 0.005 | 117 | −0.007 to 0.014 | .45 |

Predictor variables, other than years of follow-up assessment, were measured at the baseline assessment. Body fat mass was estimated with DXA. Socioeconomic status was calculated as described by Hollingshead.14 Pubertal stage, as described by Marshall and Tanner,42,43 was assessed through physical examination (Tanner stage: 1, prepubertal; 2, earliest signs of puberty; 3, midpuberty). For socioeconomic status and pubertal stage, the reference group was 5 and 3, respectively. For both dieting and binge eating, the reference group was the “never” category (0).

DISCUSSION

Among children at high risk for adult obesity, we found that reported binge eating and dieting attempts predicted increases in body fat mass. Neither depressive symptoms nor disturbed eating attitudes contributed significantly to body fat mass gain.

Our findings are notable because they are the first to examine psychological predictors of changes in body fat mass, as opposed to BMI. DXA is a highly accurate method for measuring body fat mass.33–35 Unlike BMI assessments, it allows for the examination of body fatness, exclusive of muscle mass and other organ weights that contribute to BMI. Particularly during adolescence, when gains in both muscle and bone mass can be substantial, changes in BMI may not directly reflect changes in fat mass.

The finding that children who reported dieting experienced greater fat mass growth supports 3 prior investigations that found self-labeled dieting to be a significant predictor of increased body mass among cohorts of adolescents.5,8,9 A number of hypotheses may account for this seemingly contradictory finding. First, dieting might not have been successful; restrictive diets are rarely maintained over a period of time necessary to lose substantial weight,36 and self-reported caloric intake is frequently inconsistent with actual intake.37–40 Second, successful dietary restriction might trigger compensatory overeating,41 contributing to an increased trajectory of weight gain. Last, and perhaps most likely, repeated dieting attempts before adolescence may reflect efforts by children and their parents to prevent the onset or worsening of obesity among children with unusually rapid, unremitting, weight gain. Multiple childhood dieting efforts would then be a marker for extreme susceptibility for weight gain.

Three previous prospective studies reported that binge eating was associated with gains in BMI over 2 to 4 years among adolescent girls8,10 and boys,9 whereas 1 study of adolescent girls did not find binge eating to predict obesity onset.5 Two studies by Stice et al8,10 are of note because both evaluations used measured (rather than self-reported) BMI. Consistent with most previous studies, the presence of binge eating was associated with greater fat gain in our sample.

In contrast to some studies that reported that depression in childhood3 or adolescence2,4,5 may predict weight gain, we did not find childhood depressive symptoms to be a significant independent predictor of changes in fat mass. Pine et al3 reported that children and adolescents with major depression had a twofold increased relative risk of reporting they were overweight as adults, and 3 other studies2,4,5 found that adolescents who reported depressed mood at baseline had greater increases in BMI 1 to 5 years later. The lack of relationship between depressive symptoms and weight changes in the present study might be a consequence of the age and psychological profile of our sample. Many subjects had not initiated puberty (when depression often manifests), and few children met criteria for clinical depression. It is possible that depressive symptoms, and perhaps other psychological variables, are more potent predictors of fat gain among older children. Moreover, our lack of findings may be attributable to the use of a questionnaire to assess depressive symptoms. Although the Children’s Depression Inventory is a well-validated and widely used questionnaire, 3 of the 4 prior studies that found a relationship between depression and weight gain used interview methods to assess depressive symptoms.3–5 In the present investigation, when measures of disturbed eating behaviors were also studied, depressive symptoms no longer served as a salient predictor of fat gain among children at high risk for obesity.

Limitations of the current study include the relatively small sample and the reliance on questionnaires, rather than clinical interviews, for assessment of psychological and behavioral variables. Also of note, subjects were recruited purposely either to be overweight or to be at high risk for overweight by virtue of having ≥1 overweight parent. Therefore, these findings may not be generalizable to children who are not at similar increased risk for adult obesity. Because one half of our sample was already overweight at the first assessment, our results may be most reflective of outcomes among overweight children. However, the sample is representative of a population in urgent need of intervention. Children in our sample gained almost 16 pounds per year, ~2.5 times the expected weight gain for children growing at the 50th percentile.12 Finally, although a non–treatment-seeking sample was recruited, families willing to participate in longitudinal studies may differ from those in the general population. Strengths of this investigation include the repeated measurement of body fat mass with a criterion method, the young age of participants at their initial visits, and the inclusion of measures of disturbed eating attitudes and behaviors as well as depressive symptoms.

Among children at high risk for adult obesity, those reporting dieting attempts and binge eating have greater gains in body fat mass during middle childhood. Studies evaluating the efficacy of interventions targeting disordered eating and dieting behaviors among children at high risk for obesity may lead to more-effective approaches for prevention of inappropriate weight gain.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health (grant Z01-HD-00641 to Dr. Yanovski from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development).

Abbreviations

- CI

confidence interval

- DXA

dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry

- ChEAT

Children’s Eating Attitude Test

Footnotes

The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

References

- 1.Whitaker RC, Wright JA, Pepe MS, Seidel KD, Dietz WH. Predicting obesity in young adulthood from childhood and parental obesity. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:869–873. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709253371301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goodman E, Whitaker RC. A prospective study of the role of depression in the development and persistence of adolescent obesity. Pediatrics. 2002;110:497–504. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.3.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pine DS, Goldstein RB, Wolk S, Weissman MM. The association between childhood depression and adulthood body mass index. Pediatrics. 2001;107:1049–1056. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.5.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richardson LP, Davis R, Poulton R, et al. A longitudinal evaluation of adolescent depression and adult obesity. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157:739–745. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.8.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stice E, Presnell K, Shaw H, Rohde P. Psychological and behavioral risk factors for obesity onset in adolescent girls: a prospective study. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73:195–202. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.2.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pine DS, Cohen P, Brook J, Coplan JD. Psychiatric symptoms in adolescence as predictors of obesity in early adulthood: a longitudinal study. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:1303–1310. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.8.1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bardone AM, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Dickson N, Stanton WR, Silva PA. Adult physical health outcomes of adolescent girls with conduct disorder, depression, and anxiety. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37:594–601. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199806000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stice E, Cameron RP, Killen JD, Hayward C, Taylor CB. Naturalistic weight-reduction efforts prospectively predict growth in relative weight and onset of obesity among female adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67:967–974. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.6.967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Field AE, Austin SB, Taylor CB, et al. Relation between dieting and weight change among preadolescents and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2003;112:900–906. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.4.900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stice E, Presnell K, Spangler D. Risk factors for binge eating onset in adolescent girls: a 2-year prospective investigation. Health Psychol. 2002;21:131–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hedley AA, Ogden CL, Johnson CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among US children, adolescents, and adults, 1999–2002. JAMA. 2004;291:2847–2850. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.23.2847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ogden CL, Kuczmarski RJ, Flegal KM, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2000 growth charts for the United States: improvements to the 1977 National Center for Health Statistics version. Pediatrics. 2002;109:45–60. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Guo SS, et al. 2000 CDC growth charts for the United States: methods and development. Vital Health Stat. 2000;11(246):1–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hollingshead A. Four Factor Index of Social Status. New Haven, CT: Yale University; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robotham D, Schoeller D, Mercado AB, Yanovski JA. Body fat in children is underestimated by the QDR4500 DXA relative to deuterium dilution. Presented at the Pediatric Academic Societies’ annual meeting; May 1–4, 2004; San Francisco, CA. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kovacs M. The Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) Psychopharmacol Bull. 1985;21:995–998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kovacs M. Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) Manual. North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kovacs M, Beck A. An empirical-clinical approach toward a definition of childhood depression. In: Schulterbrandt JG, Raskin AJ, editors. Depression in Childhood: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Conceptual Models. New York, NY: Raven; 1977. pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kazdin A, Petti T. Self-report and interview measures of childhood and adolescent depression. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1982;23:437–457. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1982.tb00089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson WG, Rohan KJ, Kirk AA. Prevalence and correlates of binge eating in white and African American adolescents. Eat Behav. 2002;3:179–189. doi: 10.1016/s1471-0153(01)00057-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson WG, Grieve FG, Adams CD, Sandy J. Measuring binge eating in adolescents: adolescent and parent versions of the Questionnaire of Eating and Weight Patterns. Int J Eat Disord. 1999;26:301–314. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199911)26:3<301::aid-eat8>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yanovski S. Binge eating disorder: current knowledge and future directions. Obes Res. 1993;1:306–324. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1993.tb00626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.American Psychiatric Association. Text Revision. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maloney MJ, McGuire JB, Daniels SR. Reliability testing of a children’s version of the Eating Attitude Test. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1988;27:541–543. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198809000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garner DM, Garfinkel PE, O’Shaughnessy M. The validity of the distinction between bulimia with and without anorexia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142:581–587. doi: 10.1176/ajp.142.5.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Morgan CM, Yanovski SZ, Marmarosh C, Wilfley DE, Yanovski JA. Comparison of assessments of children’s eating-disordered behaviors by interview and questionnaire. Int J Eat Disord. 2003;33:213–224. doi: 10.1002/eat.10128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fairburn C, Cooper Z. The Eating Disorder Examination. In: Fairburn CG, Wilson GT, editors. Binge Eating: Nature, Assessment and Treatment. 12. New York, NY: Guilford; 1993. pp. 317–360. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bryant-Waugh RJ, Cooper PJ, Taylor CL, Lask BD. The use of the Eating Disorder Examination with children: a pilot study. Int J Eat Disord. 1996;19:391–397. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199605)19:4<391::AID-EAT6>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steinberg E, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Cohen ML, et al. Comparison of the child and parent forms of the Questionnaire on Eating and Weight Patterns in the assessment of children’s eating-disordered behaviors. Int J Eat Disord. 2004;36:183–194. doi: 10.1002/eat.20022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Diggle PJ, Heagerty P, Liang K-Y, Zeger SL. Analysis of Longitudinal Data. 2. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sun M, Gower BA, Bartolucci AA, Hunter GR, Figueroa-Colon R, Goran MI. A longitudinal study of resting energy expenditure relative to body composition during puberty in African American and white children. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;73:308–315. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/73.2.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnson M, Figueroa-Colon R, Huang T, Dwyer J, Goran M. Longitudinal changes in body fat in African American and Caucasian children: influence of fasting insulin and insulin sensitivity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;86:3182–3187. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.7.7665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brunton JA, Bayley HS, Atkinson SA. Validation and application of dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry to measure bone mass and body composition in small infants. Am J Clin Nutr. 1993;58:839–845. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/58.6.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ellis KJ, Shypailo RJ, Pratt JA, Pond WG. Accuracy of dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry for body-composition measurements in children. Am J Clin Nutr. 1994;60:660–665. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/60.5.660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Figueroa-Colon R, Mayo MS, Treuth MS, Aldridge RA, Weinsier RL. Reproducibility of dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry measurements in prepubertal girls. Obes Res. 1998;6:262–267. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1998.tb00348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blackburn GL, Wilson GT, Kanders BS, et al. Weight cycling: the experience of human dieters. Am J Clin Nutr. 1989;49:1105–1109. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/49.5.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lichtman SW, Pisarska K, Berman ER, et al. Discrepancy between self-reported and actual caloric intake and exercise in obese subjects. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:1893–1898. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199212313272701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kretsch MJ, Fong AK, Green MW. Behavioral and body size correlates of energy intake underreporting by obese and normal-weight women. J Am Diet Assoc. 1999;99:300–306. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(99)00078-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Briefel RR, Sempos CT, McDowell MA, Chien S, Alaimo K. Dietary methods research in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: underreporting of energy intake. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;65(suppl):1203S–1209S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/65.4.1203S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Black AE, Cole TJ. Biased over- or under-reporting is characteristic of individuals whether over time or by different assessment methods. J Am Diet Assoc. 2001;101:70–80. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(01)00018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Polivy J, Herman CP. Dieting and binging: a causal analysis. Am Psychol. 1985;40:193–201. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.40.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Variations in the pattern of pubertal changes in boys. Arch Dis Child. 1970;45:13–23. doi: 10.1136/adc.45.239.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Variations in pattern of pubertal changes in girls. Arch Dis Child. 1969;44:291–303. doi: 10.1136/adc.44.235.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]