Abstract

Genital tract bacterial infections could induce abortion and are some of the most common complications of pregnancy; however, the mechanisms remain unclear. We investigated the role of prostaglandins (PGs) in the mechanism of bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced pregnancy loss in a mouse model, and we hypothesized that PGs might play a central role in this action. LPS increased PG production in the uterus and decidua from early pregnant mice and stimulated cyclooxygenase (COX)-II mRNA and protein expression in the decidua but not in the uterus. We also observed that COX inhibitors prevented embryonic resorption (ER). To study the possible interaction between nitric oxide (NO) and PGs, we administered aminoguanidine, an inducible NO synthase inhibitor. NO inhibited basal PGE and PGF2α production in the decidua but activated their uterine synthesis and COX-II mRNA expression under septic conditions. A NO donor (S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine) produced 100% ER and increased PG levels in the uterus and decidua. LPS-stimulated protein nitration was higher in the uterus than in the decidua. Quercetin, a peroxynitrite scavenger, did not reverse LPS-induced ER. Our results suggest that in a model of septic abortion characterized by increased PG levels, NO might nitrate and thus inhibit COX catalytic activity. ER prevention by COX inhibitors adds a possible clinical application to early pregnancy complications due to infections.

Keywords: embryonic resorption, uteri, decidua, peroxynitrite, sepsis

Maternal infections could cause abortion in humans (1, 2), but their mechanism is not clear. Spontaneous and cytokine-boosted abortion rates have been linked to exposure to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in the environment (3). Bacteria could enter the uterus with ejaculate or by intestinal absorption (4). Previously, we developed a mouse model to study LPS-induced pregnancy loss (5). LPS (1 μg/g i.p.) injected on day 7 of pregnancy produced 100% embryonic resorption (ER) at 24 h, with fetal expulsion at 48 h. Nitric oxide (NO) produced by inducible NO synthase (iNOS) plays a key role in ER (5). LPS produced systemic effects but did not affect the mothers' survival or future pregnancies.

Prostaglandin (PG) biosynthesis is catalyzed by cyclooxygenase (COX) I and II, the later being inducible by proinflammatory agents such as cytokines and LPS (6–8). It is well known that PGs mediate septicemic signs and symptoms of Gram-negative bacterial infections and stimulate contractility of the myometrium (9, 10). Thus, PGs are considered to be effective abortifacients and are important mediators of LPS-induced ER and preterm labor. Silver et al. (11) showed that deciduae from LPS-treated mice produce inflammatory eicosanoids as PGE2, PGF2α, and thromboxane B2 and that indomethacin (Indo), a nonselective COX inhibitor, prevents abortion.

A significant body of experimental evidence suggests a relationship between NO and PGs (12, 13), particularly in pathophysiologic events associated with gestation. In our laboratory we found that epidermal growth factor and IL-1α enhance PG production by stimulating iNOS activity (14, 15) and that Indo stimulates NO during the implantation period in the rat (16). The aim of this study was to characterize PGE and PGF2α generation in the LPS-induced ER model and to determine whether NO and PGs interact in this model.

Results

Participation of PGs in LPS-Induced ER.

Effect of COX inhibitors.

We have previously observed (5) that relatively low doses of LPS on day 7 of pregnancy produced 100% ER. The resorption process finishes when the remaining implantation sites are totally expelled by the mother without evidence of gestation a few days later.

Here we found that coinjection of LPS and Indo, a nonselective COX inhibitor, partially blocked LPS-induced ER (Table 1). Furthermore, Melo and Cele, two selective COX-II inhibitors, diminished to a higher extent the abortogenic phenotype. Animals treated with LPS + COX inhibitors did not show signs of fetal expulsion, and all of the females delivered live litters. COX inhibitors produced lower birth weight pups with normalization during lactation (data not shown). These results suggest that PGs might be involved in LPS-induced ER and that COX-II could be the implicated isoform.

Table 1.

Rate of embryonic resorption

| Treatment | % ER |

|---|---|

| Control | 5.0 ± 3.1 (n = 6) |

| LPS | 100 ± 0.0* (n = 6) |

| LPS + Indo | 53.4 ± 4.3† (n = 14) |

| LPS + Melo | 27.2 ± 2.9† (n = 8) |

| LPS + Cele | 35.6 ± 5.1† (n = 7) |

| SNAP | 100 ± 0.0* (n = 6) |

| LPS + quercetin | 85.0 ± 10.2* (n = 16) |

Day-7 pregnant mice were injected with PBS (control), LPS (1 μ g/g), LPS + Indo (2.5 mg/kg), LPS + Melo (4 mg/kg), LPS + Cele (3 mg/kg), LPS + quercetin (10 mg/kg), or SNAP alone (3 mg/kg) and were killed on day 12; % ER was calculated as mentioned before. Values are means ± SEM. ∗, P < 0.001 vs. control group; †, P < 0.01 vs. LPS-treated group.

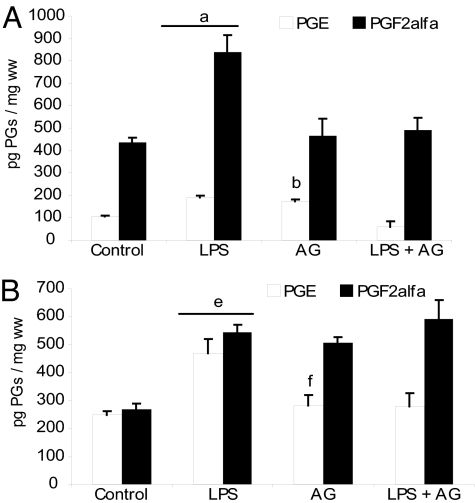

PG synthesis.

PGE and PGF2α production was detectable in both the decidua and uterus in control animals after 6 h of PBS administration. LPS increased PG production in the uterus and decidua (Fig. 1), and Indo decreased basal and LPS-stimulated PG levels in both tissues. Melo, a COX-II selective inhibitor, partially reversed PG increases in the uterus (Fig. 1A) and PGF2α synthesis in the decidua (Fig. 1B), where it completely abolished the PGE increase due to LPS. These results reinforce the idea that COX-II might be responsible for the augmented synthesis of PGs due to LPS.

Fig. 1.

In vivo effect of LPS and COX inhibitors on PG production. (A) Uterus. (B) Decidua. Day-7 pregnant mice were injected with PBS (control), LPS (1 μg/g), LPS + Melo (4 mg/kg), or LPS + Indo (2.5 mg/kg) and were killed 6 h after LPS treatment. Values are means ± SEM (n = 8). a and b, P < 0.001 vs. control group; c, P < 0.001 vs. LPS-treated mice; d, P < 0.001 vs. control group; e and f, P < 0.05 vs. control group; g, P < 0.001 vs. control group; h, P < 0.001 vs. LPS-treated mice; and i, P < 0.05 vs. LPS-treated mice.

In vitro treatment with another COX-II inhibitor, NS-398 (30 ng/ml), completely reversed PGE (uterus: LPS 459.5 ± 18.2 vs. LPS + NS-398 336.4 ± 33.1 pg/mg wet weight (ww), P < 0.05; decidua: LPS 950.6 ± 96 vs. LPS + NS-398 335.6 ± 37.2 pg/mg ww, P < 0.001) and PGF2α increases (uterus: LPS 1,034 ± 72 vs. LPS + NS-398 818.4 ± 35.8 pg/mg ww, P < 0.05; decidua: LPS 541.3 ± 20.4 vs. LPS + NS-398 407.3 ± 16.7 pg/mg ww, P < 0.05), suggesting that COX-II may increase PG synthesis due to LPS.

Although the dose of LPS administered was quite low, it produced visible systemic inflammatory effects such as diarrhea, piloerection, and bent posture (5). LPS-induced PG synthesis was only observed at the implantation sites. Other tissues such as adrenal glands did not show any change in PG content (PGF2α: control 577.4 ± 47 vs. LPS 659.7 ± 61.3 pg/mg ww; PGE: control 676.9 ± 40.5 vs. LPS 770.9 ± 56.43 pg/mg ww).

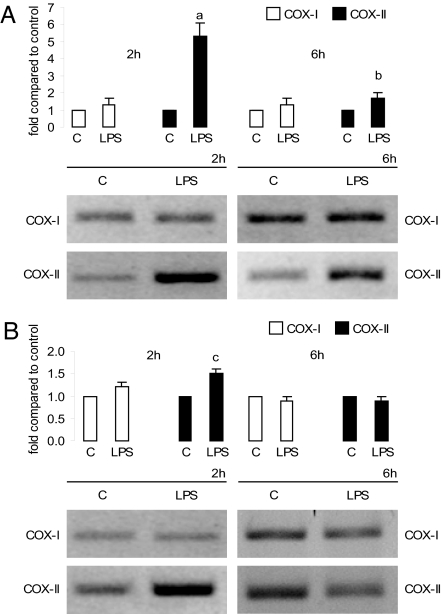

COX mRNA.

We investigated whether LPS could modulate the COX synthesis pathway. COX-I mRNA did not change in the uterus or decidua. In contrast, 2 h after LPS treatment, uterine COX-II mRNA was increased 4-fold compared with the control group (Fig. 2A). After 6 h, COX-II mRNA expression was strongly stimulated. However, in the decidua only a slight augmentation was observed (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

In vivo effect of LPS on COX mRNA levels. Uterus (A) and decidua (B) after LPS (1 μg/g) or PBS [control (C)] injection on day 7 of pregnancy. Animals were killed 2 and 6 h after treatment. (Upper) Densitometric analysis of the bands. (Lower) Representative PCR of COX-I and COX-II mRNA. Values are means ± SEM of three experiments (n = 4). a, P < 0.001 vs. control group; b and c, P < 0.05 vs. control value.

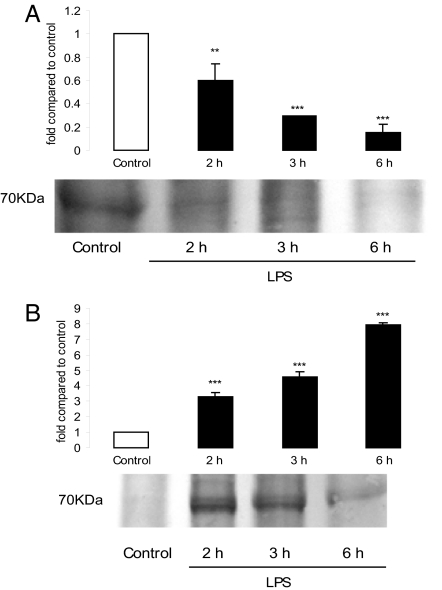

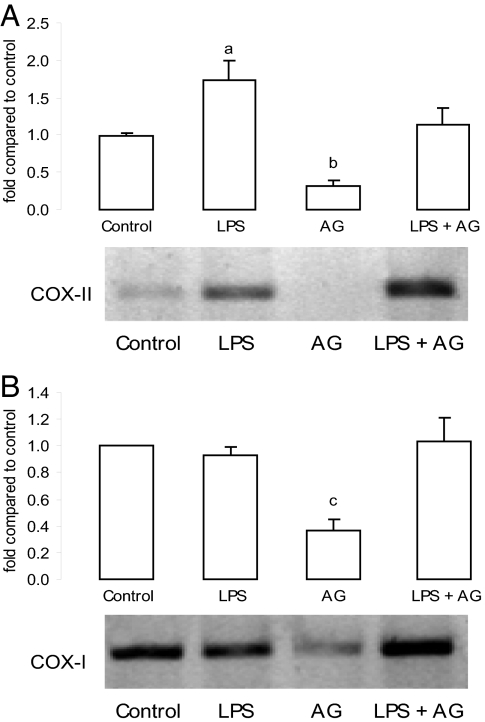

COX protein levels.

COX-I was undetectable by Western blot analysis in the uterus and decidua at any time and under any treatment (data not shown). We found a tissue and temporal regulation pattern for COX-II protein expression. Uterine COX-II protein levels decreased 3 h after LPS administration and remained low at 6 h (Fig. 3A). In the decidua, LPS increased COX-II protein levels by 2-, 4-, and 7-fold at 2, 3, and 6 h, respectively (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Effect of LPS on COX-II protein levels at 2, 3, and 6 h. (A) Uterus. (B) Decidua. (Upper) Densitometric analysis of the bands. (Lower) Representative COX-II Western blot analysis. Values are means ± SEM of three experiments (n = 4). ∗∗, P < 0.01; ∗∗∗, P < 0.001 vs. control value.

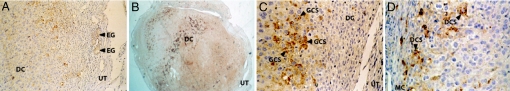

Immunolocalization of COX isoforms.

Localization of COX protein among treatment groups was examined by immunohistochemistry on day-7 implantation site sections. Tissues were removed 6 h after LPS administration when maximal NO synthesis was detected (5). Immunoreactive COX-I (sections not shown) and COX-II were present in implantation sites in all groups analyzed. Both isoforms were localized only in the decidual tissue and were not detected in the nonmodified endometrium, myometrium, or vascular smooth muscle (Fig. 4). Glandular epithelium showed low COX staining in only a few glands.

Fig. 4.

Immunolocalization of COX-II in implantation sites of treated mice. Pregnant mice were injected with PBS (control), LPS, AG (6 mg per mouse), or LPS + AG and killed 6 h after LPS injection. (A) COX-II in control animals (×100). (B) COX-II in LPS-treated deciduae (×25). (C) COX-II-positive decidual cells in AG-treated animals (×250). (D) COX-II-positive decidual cells in LPS + AG-treated animals (×250). n = 6. DC, decidua; UT, uterus; EG, endometrial glands; GCS, granular cytoplasmic stain; MC, myometrial cells; DCS, diffuse cytoplasmic stain.

The subcellular distribution patterns of COX-I and COX-II proteins were localized exclusively in the cytoplasm of decidual cells. Many decidual cells showed perinuclear labeling. These findings are in accordance with the well known subcellular localization of COX in the luminal surfaces of the endoplasmic reticulum and nuclear envelope. Some cells showed granular staining, whereas others presented a diffuse gold color throughout the cytoplasm.

Interaction Between COX and NOS Pathways.

Effect of NO on COX pathway.

It was reported that eicosanoid production may interact with the NO biosynthetic pathway (17–19). We have found that LPS produced a significant NO increase at implantation sites (5), and it is well known that PGs augment during implantation (20) and sepsis (21, 22). Thus, we investigated the possible crosstalk between NO and PG pathways in our model.

Aminoguanidine (AG), a selective iNOS inhibitor, reversed LPS-induced ER by 52% (5). Here we found that AG increased basal PGE synthesis and abolished LPS-induced PG production in the uterus (Fig. 5A). In the decidua, AG increased basal PGF2α production and did not alter PG levels in LPS + AG-treated animals (Fig. 5B). Thus, NO could have a dual role in PG synthesis. In a physiological context such as normal pregnancy, NO might inhibit PG synthesis, thus contributing to uterine quiescence. In a pathological event such as septic abortion, NO might participate in the mechanism of the LPS-induced PG increase.

Fig. 5.

In vivo effect of AG on PGE and PGF2α production. (A) Uterus. (B) Decidua. Day-7 pregnant mice were injected with PBS (control), LPS, LPS + AG (6 mg per mouse), or AG alone and killed 6 h after LPS administration. Values are means ± SEM (n = 6). a and b, P < 0.001 vs. control group; c, P < 0.001 vs. LPS-treated group; d, P < 0.05 vs. LPS-treated group; e and f, P < 0.001 vs. control group.

Then, we examined the effect of S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine (SNAP), a NO donor. SNAP administration to day-7 pregnant mice elicited 100% ER as previously observed for LPS (Table 1). In the uterus, SNAP increased PGE and PGF2α just 1 h after its administration, and they remained high until 4 and 2 h, respectively, after the SNAP treatment (Fig. 6A). In decidua, SNAP increased PGF2α at 2 h and PGE production 1, 2, and 4 h after its administration (Fig. 6B). These results suggest a critical role for NO in PG augmentation and the progression of ER.

Fig. 6.

In vivo effect of SNAP on PGE and PGF2α production. (A) Uterus. (B) Decidua. Day-7 pregnant mice were injected with PBS (control) or SNAP (3 mg/kg) and killed at 1, 2, 4, and 6 h after treatment. n = 8. a and c, P < 0.001; b, d, and g, P < 0.01; e, f, and h, P < 0.05 vs. control group.

AG decreased COX-I and COX-II mRNA levels in decidua and uterus, respectively (Fig. 7), suggesting that basal iNOS-derived NO might positively regulate COX mRNA expression. AG partially abrogated uterine LPS-induced COX-II mRNA, suggesting that NO could be participating in the effect of LPS on PG synthesis. Also, strong COX-II immunostaining was observed in AG-treated animals (Fig. 4). This suggests that NO or its metabolites could inhibit COX-II expression in LPS-treated animals.

Fig. 7.

In vivo effect of AG on COX mRNA levels. (A) Uterine COX-II mRNA. (B) Decidual COX-I mRNA. (Upper) Densitometric analysis of the bands. (Lower) Representative PCR of COX mRNA after AG (6 mg per mouse) injection on days 6 and 7 of pregnancy. Values are means ± SEM of three experiments (n = 4). a, P < 0.05 vs. LPS group; b, P < 0.001; c, P < 0.05 vs. control group.

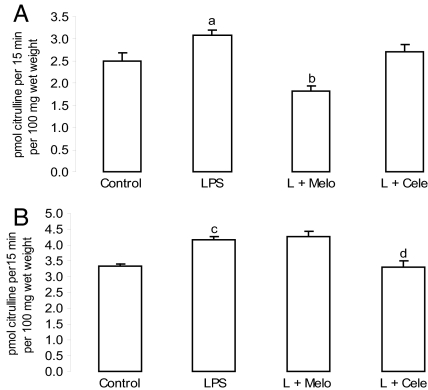

Effect of PGs on NO pathway.

COX products could modulate NOS activity (23, 24). Thus, we investigated NOS activity in the presence of selective COX inhibitors 6 h after treatment, when maximum NO production occurs because of LPS administration (5). Melo administration inhibited the LPS effect on uterine NOS activity (Fig. 8A), whereas Cele diminished it in the decidua (Fig. 8B).

Fig. 8.

In vivo effects of COX inhibitors on NOS activity. (A) Uterus. (B) Decidua. Day-7 pregnant mice were injected with PBS (control), LPS (1 μg/g), LPS + Melo (4 mg/kg), and LPS + Cele (3 mg/kg) and were killed 6 h later. Values are means ± SEM (n = 6). a, P < 0.05; c, P < 0.001 vs. control group; b and d, P < 0.001 vs. LPS group.

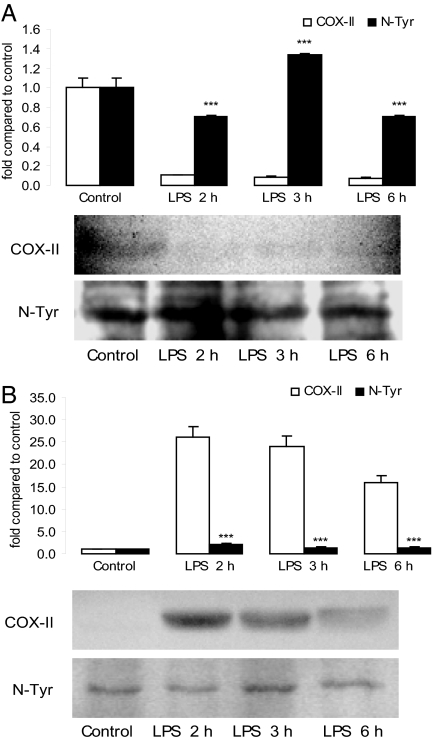

Participation of NO-derived reactive species.

Several forms of NO-derived reactive species could be synthesized in different biological systems. The administration of quercetin, a peroxynitrite scavenger (25), with LPS did not prevent LPS-induced ER (Table 1), indicating that peroxynitrite is not involved in the ER process.

Tyrosine nitration is becoming increasingly recognized as a functionally significant posttranslational protein modification that serves as an indicator of NO-mediated oxidative inflammatory reactions (26–28). We detected nitration of COX-II tyrosine residues (29, 30) at each time analyzed and in control mice injected with PBS. After LPS administration, uterine nitrated levels were higher than nonmodified COX-II expression (Fig. 9). This result suggests that LPS might induce a rapid nitration of uterine COX-II protein, which reached a maximum 3 h later. In contrast, decidual COX-II protein levels were significantly higher than nitrate COX-II expression after LPS treatment, which did not differ from control (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

COX-II tyrosine nitration (N-Tyr) pattern. (A) Uterus. (B) Decidua. (Upper) Representative densitometric analysis of the bands. (Lower) Representative COX-II Western blot analysis and nitrotyrosine immunoblot of the same membrane after stripping the first antibody. Values are means ± SEM of three experiments (n = 4). ∗∗∗, P < 0.001 vs. COX-II protein.

Discussion

Genitourinary tract or systemic infections with Gram-negative bacteria in pregnant women could cause abortion and several other perinatal complications. LPS is the most potent antigenic component of the Gram-negative bacterial cell wall and is known to modulate the expression of various proinflammatory cytokines (31). Also, it is a well-known inducer of abortion in mice as implantation sites are very sensitive to inflammation (32, 33). Relatively low doses of LPS do not endanger the survival of the mother but produce complete ER after local activation of NO production (33, 34). NO is a key signaling molecule implicated in central physiological functions (35, 36) but has toxic effects at high concentrations such as those produced in sepsis (37, 38). Some of these effects are due to peroxynitrites, which could initiate toxic reactions by introducing tyrosine nitration (39). Previously, we found that LPS-induced pregnancy loss was strongly associated with NO production in the uterus and decidua, as AG partially inhibited ER (5).

During inflammation, PGs are released in large amounts simultaneously with NO, and their overproduction could be detrimental. PGs promote uterine contractions, possibly contributing to embryonic expulsion (40, 41). Thus, the aim of this study was to characterize PG/COX pathway modulation in a mouse model of septic pregnancy loss.

We observed that COX-II-derived PG synthesis was stimulated under septic conditions in the uterus and decidua. Although COX-II mRNA expression and PG synthesis were stimulated in the uterus, COX-II protein was not increased after LPS treatment as would be expected. One possible explanation is that under septic conditions, NO-derived species could specifically modulate COX expression.

Recent results showed that NO could interfere not only with COX activity but also with COX expression. We hypothesized that NO could be regulating the COX pathway. The literature is divided with respect to whether NO activates or inhibits PG production. Here we observed that NO exerted a tissue-dependent modulation on PG production and elicited different effects, depending on whether basal or LPS-induced conditions were assessed. Thus, we decide to study the possible interaction between PG and oxidant NO-derived molecules in the ER model.

The chemistry of NO at any given moment is the key feature that determines its biological action (42, 43). NO could react with the superoxide radical and generate peroxynitrite, a key oxidant and nitrating molecule. Indeed, we identified a nitrated band that coincided with COX-II molecular weight in control and LPS-treated implantation sites and whose expression depended on the time and tissue analyzed. This result is in accordance with the reported “peroxide tone” (44) necessary for COX activation. Beharka et al. (45) provided strong evidence indicating that peroxynitrite increases COX activity (45). Our results show that LPS and SNAP increased PG synthesis and the COX-II mRNA level. These could be interpreted as an initial activation after arachidonic acid release, because uterine COX-II expression was decreased whereas nitrotyrosine-COX-II was augmented. Once the synthesizing cascade is initiated, peroxynitrite might nitrate an essential tyrosine residue in COX-II protein, making it incapable of catalysis. COX-II strong immunostaining in the AG-treated group supports this supposition. These results suggest that the NO inhibitory effect might involve nitration of COX tyrosine residues, whereas the stimulatory effect is likely to be the result of peroxynitrite functioning as a peroxide activator of PG signaling.

There is some evidence that LPS treatment decreases activity of prostaglandin 15-hydroxydehydrogenase (46), the enzyme responsible for the first step in PG degradation, in term fetal membranes (47) and that LPS alters PG 15-dehydrogenase mRNA and protein levels in mouse lung after stress (48). Therefore, LPS-induced PG levels may be due to not only increased PG synthesis but also decreased PG 15-dehydrogenase activity/expression and hence PG degradation. A possible effect of LPS on PG degradation could not be ruled out in this model. Finally, although SNAP, a NO donor, produced ER, quercetin, a flavonoid with antioxidant activity including scavenging of radicals and inhibition of lipid peroxidation, did not reverse ER, suggesting that NO per se could be an effective inducer of abortion and nitration but might not be the prevalent mechanism underlying septic pregnancy loss.

All together our work shows the relevant role that PGs might have in LPS-induced ER and the dual effect of NO on their synthesis. Importantly, the fact that COX inhibitors partially prevented septic abortion suggests that they could be used in the future as therapeutic agents in this pathological condition.

Materials and Methods

Drugs and Chemicals.

l-[14C(U)]Arginine (specific activity 360 mCi/mmol) and [5,6,8,11,12,14,15-3H(N)]-PGE2 (specific activity 150 Ci/mmol) were purchased from PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences; [5,6,8,9,11,12,14,15-3H(N)]PGFα2 (specific activity 200 Ci/mmol) was purchased from GE Healthcare Biosciences; Melo was purchased from Boehringer Ingelheim and Cele was purchased from Panalab S.A. Argentina. LPS of Escherichia coli 05:B55, Indo, AG, PGE, and PGF2α standards and secondary antibodies were from Sigma Chemical. The Dowex AG50-X8 column (Na+ form), nitrocellulose membranes, and all other Western blot reagents were from Bio-Rad. NS-398 and primary COX antibodies for Western blots were from Cayman Chemical. Polyclonal COX-I and COX-II antibodies for immunohistochemistry were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. The CSA/HRP kit and preimmune sera were purchased from Dako. All other chemicals were analytical grade.

Animals and Treatments.

BALB/c female mice from 8 to 12 weeks old were paired with adult BALB/c male mice. Day 0 of gestation was determined when the vaginal plug was observed. Animals received food and water ad libitum and were housed under controlled conditions of light (12-h light, 12-h dark) and temperature (23−25°C). Females were killed by cervical dislocation. The experimental procedures reported here were approved by the Animal Care Committee of the Centro de Estudios Farmacologicos y Botanicus-Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas de Argentina and carried out in accordance with the internationally accepted principles for the use of experimental animals.

The uterus and decidua from each implantation site were separated and immediately frozen at −70°C. For RT-PCR assays, tissues were immediately homogenized in TRIzol and frozen at −20°C. In vitro assays were performed using NS-398 (30 ng/ml). Control and LPS groups of mice were injected i.p. with PBS or LPS (1 μg/g), respectively, on day 7 of pregnancy. Cele (3 mg/kg) and Melo (4 mg/kg) were injected together with LPS and alone 4 h later. AG (6 mg per mouse) and LPS + AG groups received three doses of AG: the first dose on day 6, the second together with PBS or LPS on day 7, and the third dose 4 h later. Groups of animals injected with Indo (2.5 mg/kg), SNAP (3 mg/kg), or quercetin (10 mg/kg) received only one dose of the drug on day 7. To determine the percentage of ER, animals were injected on day 7 of pregnancy and killed on day 12.

Determination of NOS Activity.

Animals were killed 6 h after LPS injection. NOS enzyme activity was quantified by the modified method of Bredt and Snyder (49), which measures the conversion of l-[14C]arginine into l-[14C]citrulline. Samples were weighed, homogenized in Hepes buffer (20 mM Hepes, 25 mM l-valine, 0.45 mM CaCl2, and 1 mM DTT), and incubated at 37°C with 10 μM l-[14C]arginine (0.3 μCi) and 0.5 mM NADPH. After 15 min, samples were centrifuged for 10 min at 10,000 × g and applied to a Dowex AG50-X8 column (Na+ form), and l-[14C]citrulline was eluted. l-[14C]Citrulline radioactivity was measured by liquid scintillation counting. Enzyme activity is reported as picomoles of l-citrulline per 100 mg ww per 15 min.

COX Immunohistochemistry.

Animals were killed 6 h after LPS injection. Tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4°C. Paraffin-embedded tissue sections were cut at a thickness of 4 μm. Endogenous peroxidase activity was inhibited using 10% H2O2 in methanol. Sections were blocked in 5% normal horse serum and incubated overnight with either goat polyclonal IgG anti-COX-II (1:250) or mouse monoclonal IgG1 anti-COX-I (1:400). Indirect immunoperoxidase detection using a Dako LSAB+Systems K0679 kit was performed with slides without the first antibody as negative controls. Tissue sections were counterstained with hematoxylin. COX content was evaluated as the presence or absence of stained cells all over the entire section observed at different magnifications. Results were evaluated as positive fields for each section.

RT-PCR for COX-I and COX-II.

Animals were killed 2 and 6 h after LPS injection, and tissues were quickly removed. TRIzol reagent was added to samples and tissues were homogenized. RNA was extracted and transcribed with Maloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase. cDNA amplifications were performed with the following primers for COX-I (50) and COX-II: forward, 5′-TCC TCC TGG AAC ATG GAC TC-3′; reverse, 5′-CCC CAA AGA TAG CAT CTG GA-3′. β-Actin was amplified as a housekeeping control (primers: forward, 5′-TGT TAC CAA CTG GGA CGA CA-3′; reverse, 5′-TCT CAG CTG TGG TGG TGA AG-3′). PCR was performed as follows: for COX-I, 94°C, 1 min; 60°C, 30 s; 72°C, 2 min, 30 cycles; 72°C, 7 min; for COX-II and β-actin, 94°C, 5 min; 94°C, 40 s; 57°C, 30 s, 30 cycles; 72°C, 60 s; 72°C, 5 min. PCR products (COX-I, 449 bp; COX-II, 320 bp; and β-actin, 392 bp) were separated on 1.5% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide and recorded under UV light with a digital camera. The relative COX mRNA level was normalized to β-actin. Results are expressed as fold increases compared with control.

Western Blot Analysis.

Animals were killed 2, 3, and 6 h after LPS injection. Samples for COX detection were homogenized in radioimmunoprecipitation assay modified buffer (50 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.4, containing 1% Triton X-100, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, 2 μg/ml aprotinin, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 10 μg/ml DTT, 100 μg/ml soybean trypsin inhibitor, 1 mg/ml caproic acid, and 1 mg/ml benzamidine). Homogenates were sonicated for 30 s and centrifuged at 1,500 × g for 5 min. Protein concentration was determined by the Bradford assay (51). Total protein (1 mg) was immunoprecipitated with concentrated COX antibody overnight at 4°C. Samples were incubated with A-Sepharose protein and centrifuged at 15,700 × g for 1 min. Finally, samples were boiled in sample buffer. Positive controls were mouse macrophage lysate for COX-II and rat seminal vesicle for COX-I. Nitrotyrosine-COX samples were homogenized in PBS buffer with inhibitors. All samples were run in a 4% 0.125 M Tris (pH 6.8) stacking polyacrylamide gel, followed by a 10% 0.375 M Tris (pH 8.8) separating polyacrylamide gel. Proteins were transferred overnight at 4°C. Membranes were blocked in PBS containing 5% milk powder and incubated overnight at 4°C with the murine COX-II polyclonal antibody (1:500). Then they were stripped and incubated with rabbit anti-nitrotyrosine immunoaffinity-purified IgG (1:200). The second antibody (anti-rabbit Ig peroxidase, 1:5,000, containing 5% milk powder) was incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Proteins were detected using HRP-conjugated secondary antibody or chemiluminescence. Blots were recorded with a digital camera, and the intensity of bands was determined using the Image J (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) program. β-Actin was used as the loading control.

PG RIA.

PG levels were determined as in ref. 52. Values were expressed as picograms of PG synthesized per milligram of wet weight per hour.

ER Rate.

Resorption rates were calculated as (number of dead embryos/number of healthy embryos + number of dead embryos) × 100. Animals were tested for term labor, and pups were weighed until 1 month of age.

Statistics.

Statistical analyses were performed using the Instat Program (Graph Pad Software). Comparisons between values were performed using Student-Newman-Keuls multiple comparison tests and one-way ANOVA (ANOVA and significances were determined using Tukey's multiple comparison test) for unequal replicates. Differences between means were considered significant at P ≤ 0.05. Percent ER was analyzed using a χ2 test.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Fondo para la Investigación Científica y Tecnológica Grant PICT2002/10901.

Abbreviations

- PG

prostaglandin

- COX

cyclooxygenase

- ER

embryonic resorption

- NOS

NO synthase

- iNOS

inducible NOS

- AG

aminoguanidine

- Indo

indomethacin

- Melo

meloxicam

- Cele

celecoxib

- ww

wet weight.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Lamont RF, Sawant SR. Minerva Ginecol. 2005;57:423–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Penta M, Lukic A, Conte MP, Chiarini F, Fioriti P, Longhi C, Pietropaolo V, Vetrano G, Villaccio B, Deneger AM, et al. New Microbiol. 2003;26(4):329–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clark DA, Manuel J, Lee L, Chaoaut G, Gorczynski RM, Levy GA. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2004;52:370–378. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2004.00237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hamrick TS, Horton JR, Spears PA, Havell EA, Smoak IW, Orndorff PE. Infect Immun. 2003;71:5202–5209. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.9.5202-5209.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ogando DG, Paz D, Cella M, Franchi AM. Reproduction. 2003;125:95–110. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1250095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McAdam BF, Mardini IA, Habib A, Burke A, Lawson JA, Kapoor S, FitzGerald GA. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1473–1482. doi: 10.1172/JCI9523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith WL, Langenbach R. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:1491–1495. doi: 10.1172/JCI13271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Warner TD, Mitchell JA. FASEB J. 2004;18:790–804. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0645rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacobi J. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2002;59:3–8. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hertelendy F, Zakár T. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2004;70:207–222. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2003.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silver RM, Edwin SS, Trautman MS, Simmons DL, Branch DW, Dudley DJ, Mitchell MD. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:725–731. doi: 10.1172/JCI117719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salvemini D, Masferrer JL. Methods Enzymol. 1996;269:12–25. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)69005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mollace V, Muscoli C, Masini E, Cuzzocrea S, Salvemini A. Pharmacol Rev. 2005;57:217–252. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.2.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ribeiro ML, Perez Martínez S, Farina M, Ogando D, Gimeno M, Franchi AM. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 1999;61:353–358. doi: 10.1054/plef.1999.0110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farina M, Ribeiro ML, Ogando D, Gimeno M, Franchi AM. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2000;62:243–247. doi: 10.1054/plef.2000.0150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ribeiro ML, Cella M, Farina M, Franchi AM. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2004;11:191–198. doi: 10.1159/000076768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Devaux Y, Seguin C, Grosjean S, De Talancé N, Camaeti V, Burlet A, Zannad F, Meistelman C, Mertes PM, Longrois D. J Immunol. 2001;167:3962–3971. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.7.3962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clancy R, Varenika B, Huang W, Ballou L, Attur M, Amin A, Abramson SB. J Immunol. 2000;165:1582–1587. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.3.1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salvemini D. Cell Mol Life Sci. 1997;53:576–582. doi: 10.1007/s000180050074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pakrasi PL. J Exp Zool. 1997;278:53–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Homaidan FR, Chakroun I, Haidar HA, El-Sabban ME. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2002;3:467–484. doi: 10.2174/1389203023380585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fink MP. Am J Physiol. 2001;281:L534–L536. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.281.3.L534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hori M, Kita M, Torihashi S, Miyamoto S, Won KJ, Sato K, Ozaki H, Karaki H. Am J Physiol. 2001;280:G930–G938. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.280.5.G930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Uno K, Luchi Y, Fujii J, Sugata H, Iijima K, Kato K, Shimosegawa T, Yoshimura T. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;309:995–1002. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.061283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shen S-C, Lee W-R, Lin H-Y, Huang H-C, Ko C-H, Yang L-L, Chen Y-C. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002;446:187–194. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)01792-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schopfer FJ, Baker P, Freeman BA. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28:646–654. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2003.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beckman JS. Chem Res Toxicol. 1996;9:836–844. doi: 10.1021/tx9501445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Elasser T, Kahl S, Macleod C, Nicholson B, Sartin J, Li C. Endocrinology. 2004;145:3413–3423. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schildknecht S, Heinz K, Daiber A, Hamacher J, Kavalkí C, Ullrich V, Bachschmid M. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;340:318–325. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boulos C, Jiang H, Balazy M. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;293:222–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blatteis CM, Li S, Li Z, Feleder C, Perlik V. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2005;76(1–4):1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Athanassakis I, Aifantis I, Ranella A, Giouremou K, Vassiliadis S. Nitric Oxide. 1999;3:216–224. doi: 10.1006/niox.1999.0224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haddad EK, Duclos AJ, Baines MG. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1143–1152. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.4.1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gendron RL, Nestel FP, Lapp WS, Baines MG. J Reprod Fertil. 1990;90:395–402. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0900395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hertelendy F, Zakar T. Curr Pharm Des. 2004;10:2499–2517. doi: 10.2174/1381612043383926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maul H, Longo M, Saade GR, Garfield RE. Curr Pharm Des. 2003;9:359–380. doi: 10.2174/1381612033391784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coleman JW. Int Immunopharmacol. 2001;1:1397–1406. doi: 10.1016/s1567-5769(01)00086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grisham MB, Jourd′heuil D, Wink DA. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:315–321. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.276.2.G315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alvarez B, Radi R. Amino Acids. 2003;25:295–311. doi: 10.1007/s00726-003-0018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bygdeman M. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;17:707–716. doi: 10.1016/s1521-6934(03)00043-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsatsanis C, Androulidaki A, Venihaki M, Margioris AN. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2006;38:1654–1661. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brune B. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:864–869. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Colasanti M, Suzuki H. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2000;21:249–252. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01499-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bachschmid M, Schildknecht S, Ullrich V. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;338:536–542. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.08.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Beharka AA, Wu D, Serafini M, Meydani SN. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;32:503–511. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00817-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ivanov AI, Romanovsky AA. Front Biosci. 2004;9:1977–1993. doi: 10.2741/1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brown NL, Alvi SA, Elder MG, Bennet PR, Sullivan HF. Placenta. 1998;19:625–630. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4004(98)90024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hahn EL, Clancy KD, Tai HH, Ricken JD, He LK, Gamelli RL. J Trauma. 1998;44:777–782. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199805000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bredt DS, Snyder SH. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;66:9030–9033. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.22.9030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Przybylkowski A, Kurkowska-Jastrzebska I, Joniec I, Ciesielska A, Czlonkowska A, Czlonkowski A. Brain Res. 2004;1019:144–151. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.05.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bradford MM. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ribeiro ML, Aisemberg J, Billi S, Farina M, Meiss R, McCann S, Rettori V, Villalón M, Franchi AM. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:8048–8053. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502899102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]