Abstract

IL-17 is the founding member of a novel family of proinflammatory cytokines that defines a new class of CD4+ effector T cells, termed “Th17.” Mounting evidence suggests that IL-17 and Th17 cells cause pathology in autoimmunity, but little is known about mechanisms of IL-17RA signaling. IL-17 through its receptor (IL-17RA) activates genes typical of innate immune cytokines, such as TNFα and IL-1β, despite minimal sequence similarity in their respective receptors. A previous bioinformatics study predicted a subdomain in IL-17-family receptors with homology to a Toll/IL-1R (TIR) domain, termed the “SEFIR domain.” However, the SEFIR domain lacks motifs critical for bona fide TIR domains, and its functionality was never verified. Here, we used a reconstitution system in IL-17RA-null fibroblasts to map functional domains within IL-17RA. We demonstrate that the SEFIR domain mediates IL-17RA signaling independently of classic TIR adaptors, such as MyD88 and TRIF. Moreover, we identified a previously undescribed“TIR-like loop” (TILL) required for activation of NF-κB, MAPK, and up-regulation of C/EBPβ and C/EBPδ. Mutagenesis of the TILL domain revealed a site analogous to the LPSd mutation in TLR4, which renders mice insensitive to LPS. However, a putative salt bridge typically found in TIR domains appears to be dispensable. We further identified a C-terminal domain required for activation of C/EBPβ and induction of a subset IL-17 target genes. This structure-function analysis of a IL-17 superfamily receptor reveals important differences in IL-17RA compared with IL-1/TLR receptors.

Keywords: BB-loop, cytokine, inflammation, Toll/IL-1R domain, CCAAT/Enhancer binding protein

Interleukin-17 (IL-17A) is the best characterized member of a newly described cytokine family (1). Consisting of six ligands and five receptors, the IL-17 family shares minimal homology with other cytokines, and little is known about its mechanisms of signaling. IL-17 is produced primarily by T cells, particularly CD4+ but also CD8+ and γδ populations (2–4). In the classic view of T cell differentiation, T helper cells are divided into Th1 and Th2 subsets based on cytokine profiles. A major insight into IL-17's place in the immune network was made with the discovery that IL-23 promotes IL-17 expression in a unique CD4+ T cell population (5, 6), now termed “Th17” (7). Development of Th17 cells in mice is driven by TGFβ and IL-6 (8–10) via the RORγt transcription factor (11). Th17 cells produce IL-17 as well as IL-17F, TNFα, IL-6, and IL-22 (12, 13) and regulate various aspects of inflammation and autoimmunity.

The discovery of the Th17 subset resolved important ambiguities that were not adequately explained by the Th1/Th2 paradigm. For example, several diseases considered to be Th1-dominated nonetheless can develop in mice deficient in Th1 cytokines such as IL-12 or IFNγ (14, 15). Moreover, Th17 cells, IL-17, and/or IL-23 are sufficient to drive pathology in various autoimmune models, particularly rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and EAE (14, 16–19). Indeed, IL-17 is elevated in human RA (20), blocking IL-17 in collagen-induced arthritis (CIA) reduces disease (21), overexpression of IL-17 causes arthritis in rodents (22), and IL-17KO (23) or ICOSKO mice (which cannot make IL-17) are also resistant to CIA (24). In addition, IL-17 negatively impacts certain infectious conditions, such as Shistosomiasis and Helicobacter pylori infections (25–28). Accordingly, IL-17 is considered an appealing target for new anticytokine therapies (29). In contrast to its pathological properties, IL-17 is essential for mounting effective responses to many extracellular microbes, largely through regulation of neutrophil migration and granulopoiesis (30–33).

Surprisingly little is known about the nature of the IL-17R complex or its mechanisms of signaling. The first IL-17 binding protein to be identified was IL-17RA, a single transmembrane receptor with an unusually long cytoplasmic tail and almost no homology to known receptors (34). IL-17RA is ubiquitously expressed at the mRNA level, although surface expression varies widely (34, 35). Recent studies showed that IL-17RA is part of a preassembled complex that undergoes major conformational alterations after ligand binding (36). Moreover, another IL-17R superfamily member, IL-17RC, has been implicated in IL-17-mediated signal transduction (37). Thus, the IL-17R is a multimeric complex with dynamic subunit interactions.

The signaling pathways induced by IL-17 are just beginning to be elucidated. IL-17 induces most of the same genes as IL-1β and TLR ligands (38), and a complex bioinformatics analysis predicted a potential Toll-IL-1 Receptor (TIR)-like signaling domain in IL-17R family members, termed “SEFIR” (39). TRAF6 is necessary for IL-17 target gene expression (40), and two new reports show that the Act1 adaptor is downstream of IL-17 (41, 42). Both TRAF6 and Act1 are needed to activate NF-κB, and the majority of IL-17 target genes are NF-κB-dependent (35). In addition, IL-17 activates CCAAT/Enhancer binding proteins (C/EBP), particularly C/EBPβ and C/EBPδ, which are also vital for target gene expression (35, 43). Currently, very little is known about how IL-17 connects to C/EBP proteins or whether C/EBPβ and C/EBPδ are functionally redundant.

The goal of this study was to define motifs within IL-17RA that mediate signaling. Using bioinformatics and genetic approaches, we found that a membrane-proximal region encompassing the SEFIR domain is necessary for activation of NF-κB, ERK, and C/EBP and subsequent gene expression. We also identified a critical extension of this region with homology to a TIR BB-loop that is absolutely required for IL-17 function. In addition, a separable signaling motif was located in the C-terminal region of the IL-17RA cytoplasmic tail that contributes to activation of C/EBPβ but not C/EBPδ, as well as a subset of IL-17 target genes. This identifies functional subdomains in any IL-17R family member and establishes a basis to analyze this unique receptor family.

Results

System for Evaluating Functional Domains of IL-17RA.

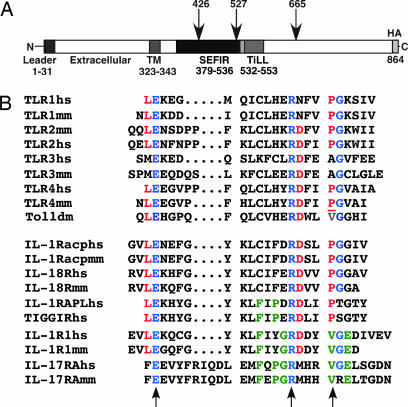

IL-17 receptors are notably distinct from other cytokine receptors in amino acid sequence (1). However, a domain with similarity to the well studied TIR domain was predicted based on sophisticated biostatistical methods, termed a “SEFIR” domain, for SEF (“similar expression to FGF receptor”) and IL-17R (39) (Fig. 1A). However, the SEFIR domain lacks important structural elements found in bona fide TIR domains, such as the “BB loop” known to be crucial for interactions between TIR-containing molecules (44). To gain insight into structure-function relationships within IL-17RA, we performed scanning and alignment of the IL-17RA cytoplasmic tail with IL-1 and TLR family members. We identified a short region downstream and slightly overlapping the SEFIR motif with homology to a BB-loop (Fig. 1B). This domain contains the glutamic acid and arginine residues that are conserved in all IL-1 and TLR BB domains (blue) (45) as well as a number of additional residues shared with IL-1R but not TLR family receptors (green). Finally, there is a valine at position 553 whose location is homologous to a valine in Drosophila Toll, where mutation destroys function (44). This site also aligns with proline-712 in murine TLR4, where a naturally occurring mutation to histidine blocks TLR4 function in LPS-resistant strains of mice (44, 46). We term this motif the “TIR-like loop” (TILL), which we hypothesized may be important for mediating IL-17RA-dependent signaling.

Fig. 1.

IL-17RA structure. (A) IL-17RA mutants used in this study. HA, hemagglutinin. TM, transmembrane. (B) Identification of a TILL. Alignment of human (hs), mouse (mm) or Drosophila (dm) TLR and IL-1R BB-loops with IL-17RA. Blue indicates amino acids conserved between the TLR/IL-1 families and IL-17RA. Red amino acids are conserved in IL-1/TLR but not in IL-17RA. Green residues are conserved in IL-1R and IL-17RA but not TLRs. The site of the LPSd mutation in mouse TLR4 is underlined. Arrows indicate conserved residues that form a salt bridge in BB-loops.

To date, structure-function studies of IL-17RA have been technically challenging because of its ubiquitous expression (34). Therefore, we immortalized tail tip fibroblasts (MFs) from IL-17RAKO mice. This system is relevant for evaluating IL-17RA function, because cells of mesenchymal origin such as fibroblasts, osteoblasts, and stromal cells are highly responsive to IL-17 (38, 47). To define regions of IL-17RA important for signaling, we created HA-tagged internal deletions and point mutations of the SEFIR and TILL domains [Fig. 1 and supporting information (SI) Fig. 6]. Constructs were transfected into IL-17RAKO MF cells, and lines that expressed high, comparable levels of receptor were chosen for analysis (SI Fig. 6A). The ability of each mutant to bind IL-17 also was verified (SI Fig. 7). In some clones, IL-17RA expression diminished over time, so expression of IL-17RA was monitored for each clone within 2 days of all experiments (data not shown).

The SEFIR and TILL Domains Are Necessary for IL-17-Dependent Signaling.

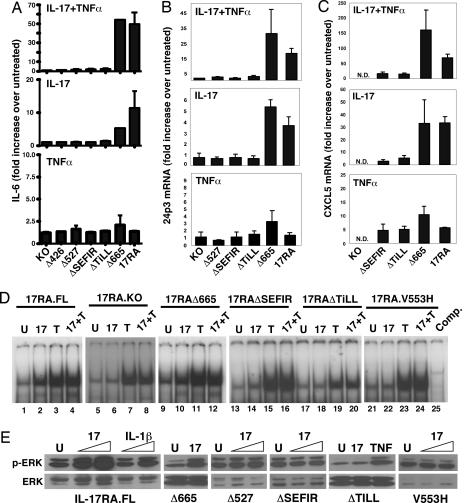

We and others have identified panels of IL-17 target genes in mesenchymal cell types (38, 47). We used representative genes to monitor signaling by the IL-17RA mutants described above, including IL-6, 24p3, and CXCL5 (LIX) and C/EBPδ. The full length (FL) IL-17RA and the IL-17RAΔ665 deletion both induced strong secretion of IL-6 after IL-17 treatment. Similar results were seen with IL-17 in combination with suboptimal doses of TNFα (Fig. 2A). As shown, the dose of TNFα used in these experiments did not trigger appreciable IL-6 expression. Cells expressing the IL-17RAΔ527 mutant, which deletes the TILL and part of the SEFIR, did not produce IL-6 after IL-17 and/or TNFα treatment. Consistently, the IL-17RAΔ426 mutant was completely defective in IL-17 signaling to IL-6. Finally, deletion of either the SEFIR or TILL domains individually resulted in a failure to respond to IL-17 (Fig. 2A). A similar pattern was seen for IL-17 induction of 24p3, CXCL5, and CXCL1; that is, IL-17RA.FL and IL-17RAΔ665 induced IL-17-dependent expression, whereas receptors lacking the SEFIR or TILL domains failed to respond to IL-17 (Fig. 2 B and C and data not shown). Also consistent with this, activation of the 24p3 promoter was induced by IL-17RA.FL and IL-17RAΔ665 but not by deletions lacking SEFIR and/or TILL (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

The SEFIR and TILL domains are required for IL-17 target gene expression and NF-κB activation. IL-17RAKO cells expressing the indicated receptors were stimulated in triplicate with IL-17 (100 ng/ml) and/or TNFα (2 ng/ml) for 4 h. (A) Expression of IL-6 was assessed by ELISA. (B and C) 24p3 and CXCL5 were assessed by real-time RT-PCR. Data are presented as fold increase over untreated (normalized to GAPDH) for each cell line. (D) IL-17RAKO cells stably expressing the indicated IL-17RA constructs were stimulated for 30 min with nothing (“U”), IL-17, and/or TNFα. Nuclear extracts were subjected to EMSA with an NF-κB probe. (E) The indicated cell lines were stimulated with IL-17 (100 ng/ml), IL-1β (20 ng/ml), or TNFα (20 ng/ml) and lysates were immunoblotted with Abs to phospho-ERK1/2 (Upper) or total ERK (Lower).

Because IL-6, 24p3, CXCL5, and CXCL1 are regulated by NF-κB, we examined the ability of IL-17RA mutants to activate NF-κB by EMSA. As expected, IL-17RA.FL triggered a strong DNA binding activity (Fig. 2D), which was confirmed to be NF-κB by competition and supershifting (data not shown). The IL-17RAΔ665 mutant induced NF-κB to a similar magnitude, but the IL-17RAΔSEFIR and IL-17RAΔTILL mutants failed to induce NF-κB. Thus, the SEFIR and TILL domains mediate NF-κB activation and expression of NF-κB-dependent genes.

IL-17 has been reported to activate various MAPK pathways, and AP1 sites are statistically overrepresented in IL-17 target promoters (35, 40, 48–50). Neither p38 nor JNK were activated by IL-17 in this cell background (data not shown). However, activation of ERK1/2 was preserved in the FL and IL-17RAΔ665 mutant, but not in receptors with mutations in SEFIR or TILL (Fig. 2E). Therefore, the SEFIR/TILL motif is also upstream of ERK.

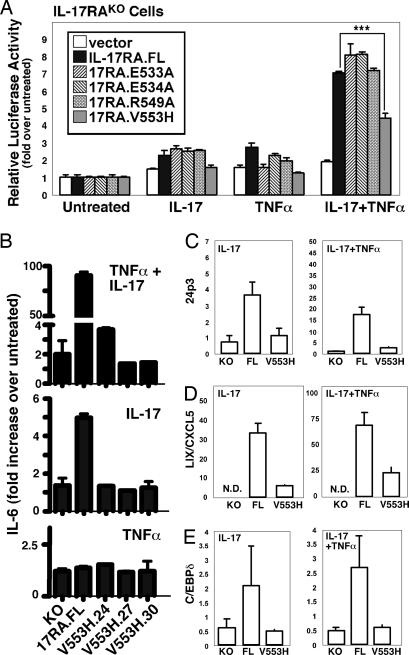

C/EBPβ Is Activated by Two Distinct Domains Within IL-17RA.

C/EBPβ and C/EBPδ are key transcription factors activated by IL-17, and both IL-6 and 24p3 contain essential C/EBP sites in their proximal promoters (35, 43). The mechanism by which IL-17 activates C/EBP is unclear, but expression of C/EBPβ and C/EBPδ mRNA and protein are enhanced in response to IL-17 and/or TNFα. Moreover, overexpression of C/EBPβ or C/EBPδ can partially substitute for IL-17 signaling (38, 43). Here, we show that the TILL and SEFIR domains are required for up-regulation of C/EBPδ (Fig. 3 A and B). C/EBPβ mRNA was not substantially enhanced by IL-17 and/or TNFα in IL-17RA.FL cells (data not shown). However, the LAP* isoform of C/EBPβ was strongly induced in IL-17RA.FL but not IL-17RAKO, IL-17RAΔSEFIR, or IL-17RAΔTILL cells. Unexpectedly, IL-17-mediated induction of C/EBPβ was impaired in IL-17RAΔ665 cells (Fig. 3B), indicating that C/EBPβ expression also is regulated by a region downstream of residue 665. Consistent with this observation, IL-17-mediated induction of C/EBP DNA binding was reduced in cells expressing IL-17RAΔ665 compared with IL-17RA.FL (Fig. 3C). In light of this finding, it was surprising that IL-17 induction of 24p3, IL-6, and CXCL5 were not compromised in IL-17RAΔ665-expressing cells (Fig. 2). However, expression of CCL2 and CCL7 were reduced in IL-17RAΔ665 cells (Fig. 3D), suggesting that certain genes may have a stronger dependence on C/EBPβ than others. Collectively, these data indicate that (i) expression of both C/EBPδ and C/EBPβ is regulated through the SEFIR/TILL domain, (ii) regulation of C/EBPβ also involves signals from a distal region in the IL-17RA tail, and (iii) signals through this distal domain activate some but not all IL-17 target genes (SI Fig. 8).

Fig. 3.

Activation of C/EBP transcription factors requires the SEFIR/TILL domain and a distal domain of the IL-17RA tail. (A) Up-regulation of C/EBPδ requires the SEFIR/TILL domain. C/EBPδ mRNA was assessed by real-time RT-PCR after 4 h of stimulation. Data are presented as fold increase over untreated (normalized to GAPDH) for each line. (B) Compromised expression of C/EBPβ in IL-17RAΔ665 cells. Expression of C/EBPβ and C/EBPδ was assessed by Western blotting lysates from the indicated cell lines. (C) Compromised C/EBPβ DNA binding in IL-17RAΔ665 cells. Indicated cells were stimulated for 4 h with IL-17 and/or TNFα and nuclear extracts subjected to EMSA with a probe corresponding to the 24p3 C/EBP site (35). Competition with 50× unlabeled probe confirms specificity (lane 12). (D) Compromised expression of CCL2 and CCL7 in IL-17RAΔ665 cells. Indicated lines were stimulated with IL-17 and/or TNFα for 4 h, and gene expression was assessed by real-time RT-PCR. Data are presented as fold increase over untreated (normalized to GAPDH) for each line.

Identification of Essential Amino Acid Residues in the TILL Motif.

Some of the conserved residues within the TILL motif correspond to residues in the BB-loop that form a key salt bridge; namely, Glu-533 or Glu-534 with Arg-549. In addition, the TILL contains a conserved valine at position 553 that corresponds to an essential residue in Drosophila Toll and murine TLR4 (44, 46). To test the hypothesis that the TILL domain forms a structure similar to a BB-loop, we mutated the charged residues to Ala or Val-553 to His and evaluated the ability to activate IL-17-dependent signaling. IL-17RAKO cells were transiently transfected with IL-17RA.FL or the mutant receptors and a 24p3 promoter-luciferase reporter (38). Surprisingly, all of the putative salt bridge mutants were fully competent to activate the reporter in response to IL-17 and/or TNFα (Fig. 4A). However, the IL-17RA.V553H mutant showed considerably impaired signaling activity. Therefore, stable IL-17RAKO cells expressing IL-17RA.V553H were created to determine whether this mutant was defective in other TILL-dependent signaling events. In three independent lines, IL-17-mediated IL-6 expression was blocked (Fig. 4B). Similarly, IL-17-mediated induction of 24p3, CXCL5, C/EBPδ, C/EBPβ, and NF-κB were impaired (Figs. 2D and 4 C–E). Thus, the TILL domain appears to contain some structural similarities to a genuine TIR domain but also has important disparities that are likely to be the basis for differences between IL-17RA and classic TIR domain-containing receptors.

Fig. 4.

A point mutation in TILL renders IL-17RA nonfunctional. (A) Valine-553 is an essential residue in the TILL domain. IL-17RAKO cells were transiently transfected in triplicate with a vector control, IL-17RA.FL, or the indicated mutations together with a 24p3-promoter-luciferase reporter. Cells were stimulated with IL-17 and/or TNFα for 6h and normalized to Renilla-Luciferase. (B–E) Valine-553 in the TILL domain is essential for IL-17 target gene expression. The indicated cell lines were incubated with IL-17 and/or TNFα for 24 h, and IL-6 was assessed in triplicate by ELISA (A). 24p3, CXCL5, and C/EBPδ were assessed by real-time RT-PCR (C–E). Data are presented as fold increase over untreated (normalized to GAPDH) for each line.

IL-17RA Does Not Use Canonical TIR Signaling Intermediates.

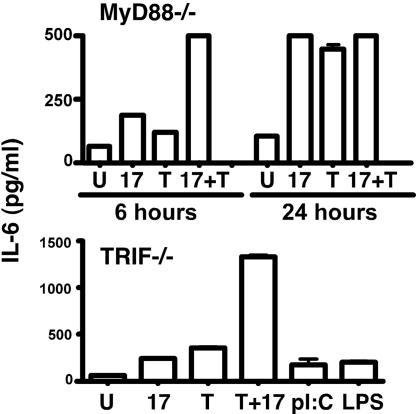

In the IL-1/TLR family, the TIR domain is critical for engaging adaptors that lead to activation of TRAF6. There is convincing evidence that TRAF6 is a key downstream mediator of IL-17-dependent signal transduction, and IL-17RA can bind TRAF6 in overexpression systems (40). However, IL-17RA does not contain a canonical TRAF6-binding motif (51) and, thus, is unlikely to bind TRAF6 directly. Because TILL resembles the TIR BB-loop, we speculated that IL-17 might employ the canonical TLR and IL-1R adaptor, MyD88. However, MyD88-deficient fibroblasts induced potent IL-17-dependent IL-6 expression (Fig. 5). Similarly, TRIF-deficient cells also induced strong IL-17-dependent signaling (Fig. 5). Coupled with the recent finding that IL-17 activates Act1 (41, 42), these data suggest that immediate proximal mediators of IL-17R signaling are distinct from IL-1/TLR family adaptors.

Fig. 5.

IL-17 signals independently of MyD88 and TRIF. Murine embryonic fibroblast cells from MyD88KO or TRIFKO mice (61, 62) were treated with IL-17 and/or TNFα, poly I:C (12.5 μg/ml), or LPS (10 ng/ml) for 6 or 24 h, and IL-6 was assessed in triplicate.

Discussion

Cytokines receptors are classified into limited groups based on sequence homology, which generally share common signaling pathways. For example, Type I and II hematopoietin receptors use the JAK-STAT pathway, whereas TIR-domain receptors typically activate TRAF6 and NF-κB. Because the IL-17R superfamily shares only minimal homology with other receptors, we undertook to delineate regions within IL-17RA critical for signal transduction. We found that the “SEFIR” domain, predicted to be a potential signaling motif with distant similarity to TIR domains (39), is indeed required for IL-17-induced signaling. Consistent with this, Qian et al. (42) recently showed that a SEFIR deletion in human IL-17RA fails to bind Act1, a newly identified IL-17RA signaling molecule. In addition, we identified a region downstream of the SEFIR domain termed a TILL that is critically important for activation of NF-κB and C/EBP transcription factors and subsequent gene expression. Detailed mutagenesis of TILL indicates that this region contains features similar to TIR domains such as a key residue at position V553, analogous to Toll and TLR4, but also important differences, such as the lack of an apparent salt bridge (44). Furthermore, the C-terminal location of the TILL with respect to the SEFIR is different from TIR BB-loops, which link the second β-strand to the second α-helix (45). Therefore, it will be interesting to determine whether the TILL adopts a conformation similar to a BB-loop, or links to an as-yet-unidentified functional domain in IL-17RA. Surprisingly, we also discovered a distal domain in the IL-17RA tail that contributes to activation of C/EBPβ and is necessary for optimal induction of a subset of IL-17 target genes. To date, we have found no homology of this subdomain to other molecules.

Molecular studies of IL-17RA have been hindered by its widespread expression. In the present study, we developed an unambiguous system to analyze IL-17RA by reconstituting IL-17RA mutants in fibroblasts from IL-17RAKO mice (30). Fibroblasts and other mesenchymal cells contribute to IL-17-mediated pathology in rheumatoid synovium, probably by expression of inflammatory effectors with joint-destructive potential (20, 29). Importantly, IL-17RAKO cells reconstituted with IL-17RA activate the same genes that are induced by IL-17 in cultured fibroblasts (38, 47). Although the in vivo relevance of many IL-17 target genes has not been determined, IL-17-mediated regulation of neutrophil migration via CXC chemokines is well established in infection models (30, 52). For example, we found that IL-17RAKO mice are highly susceptible to periodontal infections; this phenotype is due largely to a severe reduction in expression of CXCL1 and CXCL5, leading to a failure of neutrophils to reach the infected gingiva (33).

Although IL-17RA was initially considered to be structurally unique (34), a bioinformatics study predicted a “SEFIR” region with homology to TIR domains (39). However, important elements were absent in this alignment, such as the BB-loop. We found a region with homology to a BB-loop within IL-17RA located downstream and slightly overlapping the SEFIR domain (Fig. 1), which we termed a TILL. Deletion of either SEFIR or TILL eliminated NF-κB- and C/EBP-dependent signaling as well as ERK activation (Figs. 2–4). Thus, the SEFIR and TILL domains comprise an extended functional region in IL-17RA required for activating downstream events. Although the three-dimensional structure of this motif remains unknown, we identified an essential amino residue, V553. This residue lies in an analogous position to Pro-712 in TLR4, which is altered to histidine in LPS-resistant C3H/HeJ mice (46). In TLRs, this residue is not required for structural integrity (44), but whether this is also true for IL-17 receptors remains to be determined. Unlike true TIR domains, there is no evidence for a stabilizing salt bridge in the TILL, because the E533A, E534A, and R549A mutants all reconstituted IL-17 signaling indistinguishably from wild type (Fig. 4A). Accordingly, it was not surprising that IL-17 signals independently of MyD88 and TRIF, adaptors that interact with TIR domains (Fig. 5). It was discovered recently that Act1 may be a key link to IL-17R signaling, and Act1 could be coimmunoprecipitated with IL-17RA through the Act1 SEFIR-like domain (41). Thus, homotypic SEFIR interactions may be analogous to TIR–TIR associations.

Whereas NF-κB is an important IL-17 signaling pathway, C/EBP transcription factors are also vital for induction of many IL-17 target genes (43). Our microarray studies showed that C/EBPδ and C/EBPβ themselves are induced by IL-17, suggesting a positive feedback loop whereby up-regulation of C/EBP amplifies expression of IL-6 and other target genes (38, 43). Although induced only mildly at the mRNA level, protein expression of both C/EBPβ and C/EBPδ is strongly enhanced by IL-17 (Fig. 3). Reconstitution of C/EBPβδKO cells with C/EBPβ or C/EBPδ can rescue IL-17-dependent IL-6 secretion and 24p3 promoter activity (53), suggesting that there is considerable redundancy in C/EBP function. However, the present study shows that regulation of C/EBPδ and C/EBPβ by IL-17 occurs by separable pathways, because the IL-17RAΔ665 mutant induces normal expression of C/EBPδ but not C/EBPβ (Fig. 3). Moreover, IL-17RAΔ665 activates some IL-17-dependent genes normally (IL-6, CXCL5, and 24p3), but not others (CCL2 and CCL7). Therefore, IL-17 uses C/EBPδ and C/EBPβ differentially to control gene expression, and these factors are clearly not entirely redundant.

Regulation of C/EBP proteins is highly complex. C/EBPδ is controlled primarily by expression rather than by posttranslational modifications. At the transcriptional level, both 5′ and 3′ promoter/enhancer regions have been described (54, 55), although the mechanism by which IL-17 regulates C/EBPδ is undefined. Our data indicate that C/EBPδ expression is downstream of SEFIR/TILL, perhaps mediated by NF-κB or ERK (Fig. 3). In contrast, C/EBPβ is largely controlled posttranslationally. C/EBPβ exists in multiple isoforms (56), and IL-17 seems to preferentially induce the largest of these, LAP* (Fig. 3). Moreover, C/EBPβ is phosphorylated on several sites, and numerous serine-threonine kinases have been implicated in its regulation (55–58). Determining the target sites on C/EBPβ required for IL-17-mediated activation and the upstream signals responsible will be essential for fully understanding the IL-17 signaling cascade.

Mapping functional domains in cytokine receptors has been enlightening in terms of understanding signal transduction. In the IL-2R, different tyrosine residues preferentially mediate STAT5 versus phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (59). Similarly, separable regions within gp130 are required for STAT activation versus MAPK activation and mediate different activities in vivo (60). The present report reveals two separable motifs involved in IL-17RA signal transduction (SI Fig. 8). The biological significance of these signaling pathways is still not fully known, but this work sets the stage for probing IL-17R superfamily members functions in vivo.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and Luciferase Assays.

IL-17RAKO fibroblasts from IL-17RAKO mice (30, 36) were immortalized with the SV40 T antigen. Murine embryonic fibroblasts were obtained from TRIF−/− (61) and MyD88−/− mice (62). All cells were cultured in α-MEM (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), with 10% FBS and antibiotics (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Cells were transfected with FuGENE 6 (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) and stable lines were selected in Zeocin (Invitrogen). Cytokines were from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). LPS and Poly I:C were from Sigma. Luciferase assays were performed as described (38).

Plasmids.

IL-17RA was generated by RT-PCR from HT-2 cells. Mutations were made by PCR and subcloned in pcDNA3.1-Zeocin (Invitrogen). Point mutations were made with the QuikChange mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and confirmed by sequencing.

ELISA and Flow Cytometry.

IL-6 ELISAs were performed with commercial kits (eBioscience, San Diego, CA). For FACS, 106 cells were stained with mAbs M177, M750, or M751, followed by anti-rat-PE (BD PharMingen, San Jose, CA). For binding studies, a cDNA encoding huIL17 fused to huFc (IgG1) was expressed in COS cells and purified over Protein A columns. Cells were stained with huIL17.Fc, followed by anti-huIgG-APC (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA). Data were analyzed on a FACSCalibur with Cell Quest software (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA).

Western Blotting, Immunoprecipitation, and EMSA.

EMSAs were performed as described (35). Antibodies to C/EBP and histone were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA), HA Abs were from Roche, and ERK Abs were from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Hummel for preparation of murine embryonic fibroblasts and S. Akira (Osaka University, Osaka, Japan) for MyD88−/− and TRIF−/− mice. S.L.G. was supported by the Arthritis Foundation and National Institutes of Health Grants AR050458 and AI43929. K.M. was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Abbreviations

- C/EBP

CCAAT/Enhancer binding protein

- FL

full length

- RA

rheumatoid arthritis

- SEFIR

SEF/IL-17R domain

- TILL

TIR-like loop

- TIR

Toll/IL-1 receptor domain.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: J.T. and D.S. own stock in Amgen.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0611589104/DC1.

References

- 1.Aggarwal S, Gurney AL. J Leukoc Biol. 2002;71:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fossiez F, Djossou O, Chomarat P, Flores-Romo L, Ait-Yahia S, Maat C, Pin J-J, Garrone P, Garcia E, Saeland S, et al. J Exp Med. 1996;183:2593–2603. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.6.2593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu XK, Clements JL, Gaffen SL. Mol Cells. 2005;20:329–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lockhart E, Green AM, Flynn J. J Immunol. 2006;177:4662–4669. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.7.4662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aggarwal S, Ghilardi N, Xie MH, De Sauvage FJ, Gurney AL. J Biol Chem. 2002;3:1910–1914. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207577200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Happel KI, Zheng M, Young E, Quinton LJ, Lockhart E, Ramsay AJ, Shellito JE, Schurr JR, Bagby GJ, Nelson S, et al. J Immunol. 2003;170:4432–4436. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.9.4432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weaver CT, Harrington LE, Mangan PR, Gavrieli M, Murphy KM. Immunity. 2006;24:677–688. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Veldhoen M, Hocking RJ, Atkins CJ, Locksley RM, Stockinger B. Immunity. 2006;24:179–189. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mangan PR, Harrington LE, O'Quinn DB, Helms WS, Bullard DC, Elson CO, Hatton RD, Wahl SM, Schoeb TR, Weaver CT. Nature. 2006;441:231–234. doi: 10.1038/nature04754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bettelli E, Carrier Y, Gao W, Korn T, Strom TB, Oukka M, Weiner HL, Kuchroo VK. Nature. 2006;441:235–238. doi: 10.1038/nature04753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ivanov I, McKenzie B, Zhou L, Tadokoro C, Lepelley A, Lafaille J, Cua D, Littman D. Cell. 2006;126:1121–1133. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tato CM, Laurence A, O'Shea JJ. J Exp Med. 2006;203:809–812. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liang SC, Tan XY, Luxenberg DP, Karim R, Dunussi-Joannopoulos K, Collins M, Fouser LA. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2271–2279. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cua DJ, Kastelein RA. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:557–559. doi: 10.1038/ni0606-557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gor DO, Rose NR, Greenspan NS. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:503–505. doi: 10.1038/ni0603-503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lubberts E, Koenders MI, van den Berg WB. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7:29–37. doi: 10.1186/ar1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Langrish CL, Chen Y, Blumenschein WM, Mattson J, Basham B, Sedgwick JD, McClanahan T, Kastelein RA, Cua DJ. J Exp Med. 2005;201:233–240. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sato K, Suematsu A, Okamoto K, Yamaguchi A, Morishita Y, Kadono Y, Tanaka S, Kodama T, Akira S, Iwakura Y, et al. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2673–2682. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lubberts E, van den Bersselaar L, Oppers-Walgreen B, Schwarzenberger P, Coenen-de Roo CJ, Kolls JK, Joosten LA, van den Berg WB. J Immunol. 2003;170:2655–2662. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.5.2655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kotake S, Udagawa N, Takahashi N, Matsuzaki K, Itoh K, Ishiyama S, Saito S, Inoue K, Kamatani N, Gillespie MT, et al. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:1345–1352. doi: 10.1172/JCI5703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lubberts E, Koenders MI, Oppers-Walgreen B, van den Bersselaar L, Coenen-de Roo CJ, Joosten LA, van den Berg WB. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:650–659. doi: 10.1002/art.20001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lubberts E, Joosten LA, van de Loo FA, Schwarzenberger P, Kolls J, van den Berg WB. Inflamm Res. 2002;51:102–104. doi: 10.1007/BF02684010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakae S, Nambu A, Sudo K, Iwakura Y. J Immunol. 2003;171:6173–6177. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.11.6173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nurieva RI, Treuting P, Duong J, Flavell RA, Dong C. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:701–706. doi: 10.1172/JCI17321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 25.Luzza F, Parrello T, Monteleone G, Sebkova L, Romano M, Zarrilli R, Imeneo M, Pallone F. J Immunol. 2000;165:5332–5337. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.9.5332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kullberg MC, Jankovic D, Feng CG, Hue S, Gorelick PL, McKenzie BS, Cua DJ, Powrie F, Cheever AW, Maloy KJ, et al. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2485–2494. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hue S, Ahern P, Buonocore S, Kullberg M, Cua D, McKenzie B, Powrie F, Malloy K. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2473–2483. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rutitzky LI, Lopes da Rosa JR, Stadecker MJ. J Immunol. 2005;175:3920–3926. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.6.3920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lubberts E. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2003;4:572–577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ye P, Rodriguez FH, Kanaly S, Stocking KL, Schurr J, Schwarzenberger P, Oliver P, Huang W, Zhang P, Zhang J, et al. J Exp Med. 2001;194:519–527. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.4.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang W, Na L, Fidel PL, Schwarzenberger P. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:624–631. doi: 10.1086/422329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kelly MN, Kolls JK, Happel K, Schwartzman JD, Schwarzenberger P, Combe C, Moretto M, Khan IA. Infect Immun. 2005;73:617–621. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.1.617-621.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu J, Ruddy M, Wong G, Sfintescu C, Baker P, Smith J, Evans R, Gaffen S. Blood. 2007 Jan 3; doi: 10.1182/blood-2005–09-010116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yao Z, Fanslow WC, Seldin MF, Rousseau A-M, Painter SL, Comeau MR, Cohen JI, Spriggs MK. Immunity. 1995;3:811–821. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90070-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shen F, Hu Z, Goswami J, Gaffen SL. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:24138–24148. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604597200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kramer J, Yi L, Shen F, Maitra A, Jiao X, Jin T, Gaffen S. J Immunol. 2006;176:711–715. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.2.711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Toy D, Kugler D, Wolfson M, Vanden Bos T, Gurgel J, Derry J, Tocker J, Peschon JJ. J Immunol. 2006;177:36–39. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shen F, Ruddy MJ, Plamondon P, Gaffen SL. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;77:388–399. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0904490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Novatchkova M, Leibbrandt A, Werzowa J, Neubuser A, Eisenhaber F. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28:226–229. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00067-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schwandner R, Yamaguchi K, Cao Z. J Exp Med. 2000;191:1233–1239. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.7.1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chang SH, Park H, Dong C. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:35603–35607. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600256200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Qian Y, Liu C, Hartupee J, Altuntas CZ, Gulen MF, Jane-Wit D, Xiao J, Lu Y, Giltiay N, Liu J, et al. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:247–256. doi: 10.1038/ni1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ruddy MJ, Wong GC, Liu XK, Yamamoto H, Kasayama S, Kirkwood KL, Gaffen SL. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:2559–2567. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308809200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu Y, Tao X, Shen B, Horng T, Medzhitov R, Manley J, Tong L. Nature. 2000;408:111–115. doi: 10.1038/35040600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rock F, Hardiman G, Timans J, Kastelein R, Bazan J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:588–593. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.2.588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Poltorak A, He X, Smirnova I, Liu MY, Van Huffel C, Du X, Birdwell D, Alejos E, Silva M, Galanos C, et al. Science. 1998;282:2085–2088. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Park H, Li Z, Yang XO, Chang SH, Nurieva R, Wang YH, Wang Y, Hood L, Zhu Z, Tian Q, et al. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1133–1141. doi: 10.1038/ni1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jovanovic D, di Battista JA, Martel-Pelletier J, Jolicoeur FC, He Y, Zhang M, Mineau F, Pelletier J-P. J Immunol. 1998;160:3513–3521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Faour WH, Mancini A, He QW, Di Battista JA. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:26897–26907. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212790200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Granet C, Miossec P. Cytokine. 2004;26:169–177. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pullen SS, Dang TT, Crute JJ, Kehry MR. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:14246–14254. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.20.14246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Linden A, Laan M, Anderson G. Eur Respir J. 2005;25:159–172. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00032904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ruddy MJ, Shen F, Smith J, Sharma A, Gaffen SL. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;76:135–144. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0204065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cantwell CA, Sterneck E, Johnson PF. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:2108–2117. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.4.2108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yamada T, Tsuchiya T, Osada S, Nishihara T, Imagawa M. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;242:88–92. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ramji DP, Foka P. Biochem J. 2002;365:561–575. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tang QQ, Gronborg M, Huang H, Kim JW, Otto TC, Pandey A, Lane MD. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:9766–9771. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503891102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kalvakonalu D, Roy S. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2005;25:757–769. doi: 10.1089/jir.2005.25.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gaffen SL. Cytokine. 2001;14:63–77. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2001.0862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sims N, Jenkins B, Quinn J, Nakamura A, Glatt M, Gillespie M, Ernst M, Martin T. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:379–389. doi: 10.1172/JCI19872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yamamoto M, Sato S, Hemmi H, Hoshino K, Kaisho T, Sanjo H, Takeuchi O, Sugiyama M, Okabe M, Takeda K, et al. Science. 2003;301:640–643. doi: 10.1126/science.1087262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Adachi O, Kawai T, Takeda K, Matsumoto M, Tsutsui H, Sakagami M, Nakanishi K, Akira S. Immunity. 1998;9:143–150. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80596-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.