Abstract

In a recent series of ground-breaking experiments, Nakajima et al. [Nakajima M, Imai K, Ito H, Nishiwaki T, Murayama Y, Iwasaki H, Oyama T, Kondo T (2005) Science 308:414–415] showed that the three cyanobacterial clock proteins KaiA, KaiB, and KaiC are sufficient in vitro to generate circadian phosphorylation of KaiC. Here, we present a mathematical model of the Kai system. At its heart is the assumption that KaiC can exist in two conformational states, one favoring phosphorylation and the other dephosphorylation. Each individual KaiC hexamer then has a propensity to be phosphorylated in a cyclic manner. To generate macroscopic oscillations, however, the phosphorylation cycles of the different hexamers must be synchronized. We propose a novel synchronization mechanism based on differential affinity: KaiA stimulates KaiC phosphorylation, but the limited supply of KaiA dimers binds preferentially to those KaiC hexamers that are falling behind in the oscillation. KaiB sequesters KaiA and stabilizes the dephosphorylating KaiC state. We show that our model can reproduce a wide range of published data, including the observed insensitivity of the oscillation period to variations in temperature, and that it makes nontrivial predictions about the effects of varying the concentrations of the Kai proteins.

Cyanobacteria are the simplest organisms to use circadian rhythms to anticipate the changes between day and night. In the cyanobacterium Synechococcus elongatus, the three genes kaiA, kaiB, and kaiC are the central components of the circadian clock (1). In higher organisms, it is believed that circadian rhythms are driven primarily by transcriptional feedback (2). KaiC phosphorylation, however, shows a circadian rhythm even when transcription and translation are inhibited (3). Still more remarkably, it was recently shown that this rhythmic KaiC phosphorylation can be reconstituted in vitro in the presence of only KaiA, KaiB, and ATP (4). The Kai system thus represents a very rare example of a functional biochemical circuit that can be recreated in the test tube. It is a major open question to explain how stable oscillations can result from the experimentally observed interactions among the different Kai proteins.

In living cells, KaiC phosphorylation increases during the subjective day and decreases during the subjective night, and this phosphorylation in turn regulates KaiC's activity as a global transcriptional repressor (5). KaiC forms a hexamer both in vivo and in vitro (6); KaiA is present in the cell as a dimer (6) and KaiB as a dimer (6, 7) or a tetramer (8). KaiC has both autodephosphorylation and weaker autophosphorylation activity, with the latter dependent on ATP binding (9–14). KaiC phosphorylation is stimulated by KaiA (10, 11, 15), whereas KaiB appears to interfere with this effect (10–12, 16). KaiC hexamers form heteromultimeric complexes with KaiA and KaiB dimers, but one such complex contains no more than one KaiC hexamer (6, 7, 17). The composition of these complexes varies with an ≈24-h period.

The striking observation of Nakajima et al. (4) of in vitro oscillations in KaiC phosphorylation poses an obvious challenge for modelers. Not only is there the potential for detailed comparisons between a model's predictions and the wealth of experimental data, the Kai system also has several novel features. Most notably, ATP is consumed, and the system is driven out of equilibrium, only through the repeated phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of KaiC. Other reactions, such as the (un)binding of KaiA and KaiB to KaiC, should thus obey detailed balance. Moreover, unlike in most biological oscillations (18), in the Kai system the proteins are neither created nor destroyed. This imposes significant constraints on any model that hopes to explain the in vitro oscillations.

Several previous studies have put forward interesting ideas on how these oscillations might occur (19–21). However, they either require that KaiC hexamers can bind to each other to form higher-order complexes (19, 20), a possibility ruled out by recent experiments (6, 7), or they assume that KaiA and KaiB can each take on multiple forms (21). In the latter case, the authors propose that these forms may correspond to different subcellular localizations, but that suggestion cannot hold for the in vitro system. Emberly and Wingreen (19) introduced the elegant hypothesis that exchange of monomers among KaiC hexamers might contribute to oscillations, an idea supported by recent observations (7). Their own work, however, shows that such exchange by itself is insufficient to produce sustained oscillations. Thus, there clearly is another mechanism at work in the Kai system.

Here, we propose such a mechanism. Our model is built on two key elements. First, we hypothesize that an isolated KaiC hexamer already has a tendency to be cyclically phosphorylated and dephosphorylated as it flips between two allosteric states. Second, we suggest that these noisy oscillations of individual hexamers can be synchronized through the phenomenon of differential affinity, whereby the laggards in a population outcompete the other hexamers for a limited number of KaiA molecules that stimulate phosphorylation. The slowest hexamers thus speed up while the fastest are forced to slow down, causing the entire population to oscillate in phase.

In the rest of this article, we first show how a simple picture of allosteric transitions in KaiC leads each hexamer to have an intrinsic phosphorylation cycle. We then use an idealized model to introduce the concept of differential affinity. This model shows that the mechanism requires only a few generic ingredients, suggesting that the same synchronization principle could be at work in other biological systems. Finally, we turn to a more complicated model of the Kai system. This model reproduces the phosphorylation behavior of KaiC not only in the in vitro experiments in which all three Kai proteins are present, but also in systems where KaiA and/or KaiB are absent. In fact, we found that the experiments on the various subsets of the three Kai proteins strongly constrain the model's design. Beyond synchronizing oscillations, KaiA and KaiB must also stabilize one or the other KaiC state by binding to it. When this binding is strong enough, the system moreover exhibits temperature compensation, as observed (4).

Allosteric Model

In this section, we introduce a simple model of allosteric transitions in KaiC that naturally gives rise to repeated rounds of phosphorylation and dephosphorylation within each hexamer. Allosteric conformational changes are widespread in biochemistry, and the conformations of members of the RecA/DnaB superfamily, to which KaiC belongs, have been extensively studied (22, 23).

KaiC Monomers.

Although there is strong evidence that KaiC monomers can be phosphorylated at multiple sites (10, 24, 25), most published data do not distinguish between different phosphorylated forms. We thus assume that KaiC monomers have only two phosphorylation states, phosphorylated and unphosphorylated.

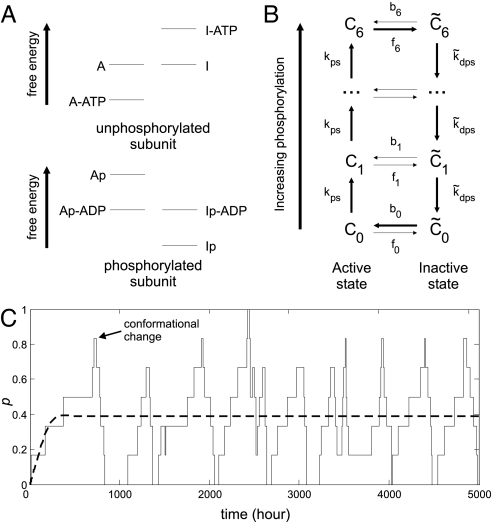

We postulate that an individual KaiC monomer can be in either an active (A) or an inactive (I) conformation. Fig. 1A shows the free energies of the different monomer states; we consider ATP binding only to unphosphorylated and ADP binding only to phosphorylated monomers. As the figure indicates, we assume that phosphorylation favors the inactive over the active state. Nucleotides have a higher affinity for monomers in the active state than for those in the inactive state, so nucleotide binding favors the active state over the inactive one. We also take both the transfer of a phosphate from ATP to a KaiC monomer and the removal of the phosphate from the monomer to be thermodynamically favorable. Taken together, these elements allow for a phosphorylation cycle: unphosphorylated monomers prefer to be in the A state, where ATP hydrolysis drives phosphorylation, whereas phosphorylated monomers prefer to be in the I state, where dephosphorylation occurs spontaneously. Each monomer thus tends to go through the sequence of reactions A → A-ATP → Ap-ADP → Ip-ADP → Ip → I → A, during which one ATP molecule is hydrolyzed.

Fig. 1.

Model of conformational transitions in individual KaiC hexamers. (A) Schematic free energy levels for KaiC subunits. Subunits can be in the active (A) or the inactive (I) state. Furthermore, subunits can be phosphorylated (p) and bind ATP or ADP. Phosphorylation favors the inactive state, and nucleotide binding favors the active state. (B) Reaction network for a KaiC hexamer with six phosphorylation sites. Ci and C̃i denote a hexamer with i phosphorylated monomers in, respectively, the active and inactive state. (C) Phosphorylation cycles for the model in B. The phosphorylation level p of a single KaiC hexamer, as obtained by stochastic simulations (solid line), and of a population of hexamers, obtained from the mean-field rate equations (dashed line). The phosphorylation level p ≡ Σi i([Ci] + [C̃i])/Σi 6([Ci] + [C̃i]), where [Ci] is the concentration of hexamers in state Ci. For parameter values, see SI Appendix.

KaiC Hexamers.

In the spirit of the MWC model (26), we assume that the energetic cost of having two different monomer conformations in the same hexamer is prohibitively large. We can then speak of a hexamer as being in either the A or the I state. The total (free) energy of the hexamer is simply the sum of the contributions from its constituent monomers. Highly phosphorylated hexamers thus prefer to be in the I state, where they will be dephosphorylated, whereas weakly phosphorylated hexamers prefer the A state, where they will be phosphorylated. As a result, each hexamer tends to go through a cycle in which it is first phosphorylated, then dephosphorylated, as indicated in Fig. 1B and Fig. 8 of the supporting information (SI) Appendix.

The transition (or flip) rates fi for a hexamer with i phosphorylated monomers to go from the A to the I state and bi to go from the I to the A state depend on the energy barriers to the conformational changes. If we assume that ATP and ADP exchange are fast, so that the free energy of each state is well defined, then the difference in free energy ΔG between the I and A states grows linearly with i: ΔG(i) = i ΔGp + (6 − i) ΔGu, where the subscripts p and u refer to the free-energy differences for phosphorylated and unphosphorylated monomers, respectively. The natural phenomenological assumption is then that the flip rates depend exponentially on the free-energy difference:

where k0 sets the basic time scale and c = exp[(ΔGp − ΔGu)/2]. Alternatively, one can develop an explicit transition state theory that includes the number of bound nucleotides as one of the order parameters for the conformational transition (see SI Appendix). This leads to flipping rates that vary exponentially with i just as in Eqs. 1 and 2. In either case, the rates depend strongly on the phosphorylation level, with the consequence that hexamers can flip from A to I only when most of their monomers are phosphorylated, and from I to A only when most are not phosphorylated.

In Fig. 1C, we show the time dependence of the phosphorylation level of a single KaiC hexamer obtained by Monte Carlo simulations of the chemical master equation (see SI Appendix) (27). Initially, the KaiC hexamer is in the unphosphorylated active state, C0. KaiC (de)phosphorylation clearly occurs in a cyclic fashion, with few transitions from one conformation to the other occurring at intermediate phosphorylation. However, both the amplitude and the period of the phosphorylation cycle are highly variable. Because of this variability, the phosphorylation cycles of a population of independent KaiC hexamers will quickly dephase. As a result, in Fig. 1C the mean phosphorylation level of the KaiC population calculated by integrating deterministic rate equations based on the law of mass action shows no oscillatory behavior. To explain the oscillations observed in the in vitro Kai system, the uncoupled phosphorylation cycles of the individual KaiC hexamers need to be synchronized.

Synchronization with Differential Affinity

The natural candidates to link the phosphorylation states of different KaiC hexamers are the other two Kai proteins. Here, we present a simple model in which KaiA plays this role by catalyzing phosphorylation in the active state, while KaiB is completely absent. This model will allow us to introduce several important ideas without the distractions that a more faithful description would entail. It shows synchronized limit-cycle oscillations in KaiC phosphorylation, provided that the concentration of KaiA is sufficiently small and that KaiA binds to KaiC with differential affinity: KaiA should bind most strongly to weakly phosphorylated KaiC hexamers. Although here we limit our discussion to a particular model inspired by the Kai system, the differential affinity mechanism is also amenable to a more general, abstract formulation that we describe in SI Appendix, where we also show that the oscillations arise through a supercritical Hopf bifurcation.

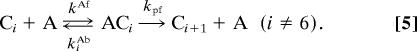

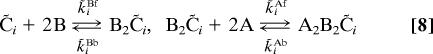

We assume that only a single dimer of KaiA can bind to a KaiC hexamer, and we force every hexamer to proceed through the states C0–C6 and C̃6–C̃0 in order (thus neglecting intermediate flips). This yields

|

We use deterministic, mass-action kinetics to model the effects of these reactions. Here, Ci and C̃i denote i-fold phosphorylated KaiC hexamers in the active and inactive states, and A denotes a KaiA dimer. Eqs. 3–5 describe the same processes within a single hexamer as the diagram in Fig. 1B, with the exception that phosphorylation of the active state now requires KaiA, which associates with active KaiC with on and off rates kAf and kiAb and stimulates phosphorylation with a rate kpf (Eq. 5). We implement differential affinity by setting kiAb = kiAbαi, with α > 1 (see SI Appendix).

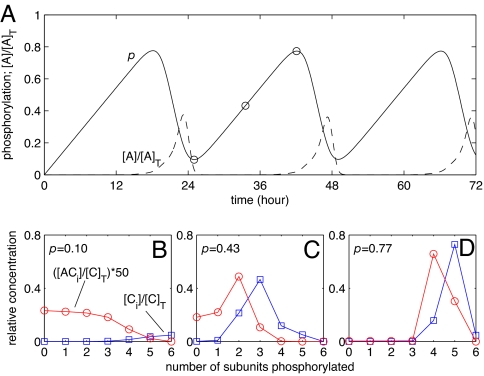

Fig. 2A shows the mean phosphorylation level of a population of KaiC hexamers as a function of time. In contrast to the behavior seen in Fig. 1C, there are clear oscillations: The KaiA dimers effectively couple the phosphorylation cycles of the individual KaiC hexamers. During the phosphorylation phase of the oscillations, most hexamers are in the active form. In this state, they can bind KaiA, which stimulates their phosphorylation. The concentration of KaiA, however, is limited; indeed, in this part of the cycle, the concentration of free KaiA is close to zero (Fig. 2A). This means that the KaiC hexamers compete with one another for KaiA. In this competition, the complexes with a lower degree of phosphorylation have the advantage because they have a higher affinity for KaiA. Hence, during the phosphorylation phase, KaiA will be mostly bound to the lagging hexamers. This is shown in Fig. 2B, where the concentrations [Ci] and [ACi] are plotted versus i for three different time points. The distributions do not overlap: KaiA has a clear preference for the less phosphorylated KaiC hexamers. Because the phosphorylation rate depends on the amount of bound KaiA, laggards with a low degree of phosphorylation will be phosphorylated at a high rate, whereas front-runners with a high degree of phosphorylation will be unable to increase their phosphorylation level further. This is the essence of the differential affinity synchronization mechanism.

Fig. 2.

Limit cycle oscillations in KaiC phosphorylation for the simplified model defined by Eqs. 3–5. (A) Mean phosphorylation level p and normalized concentration of free KaiA [A]/[A]T. During the phosphorylation phase, [A] drops almost to zero. (B–D) KaiA binding at three stages of the phosphorylation phase, marked by circles in A. KaiA favors the less phosphorylated KaiC hexamers. [C]T, total KaiC concentration; ACi, complex of KaiA and Ci. We take [A]T/[C]T = 0.02 and initially set [C0] = [C]T; see SI Appendix for other parameters.

Full Model of the Kai System

The simple model of the previous section showed how differential affinity can synchronize the oscillations of the different KaiC hexamers. This model, however, neglects KaiB completely and is not consistent with the large body of experimental data on the Kai system. Here, we present a more refined allosteric model.

The Model.

The key ingredients of our model are as follows.

KaiA can bind to the active form of KaiC, stimulating KaiC phosphorylation. Recent experiments suggest that, in the absence of KaiB, KaiA binds as a single dimer to the CII domain of the KaiC hexamer (28). Because this is the domain containing KaiC's phosphorylation site, it seems reasonable that the affinity of KaiA might depend on the phosphorylation state of KaiC. We thus assume, as before, that a single KaiA can bind to the active state of KaiC and that the affinity of KaiA for active KaiC decreases as the phosphorylation level increases.

The active state of KaiC is more stable than the inactive one. The experiments described in refs. 3 and 7 show that in the presence of only KaiA, KaiC becomes very highly phosphorylated. In the absence of KaiB, KaiC should thus have no tendency to cyclically phosphorylate and dephosphorylate. This requires that the active state of KaiC has a lower free energy than the inactive one (thus shifting the energy levels in Fig. 1A from their symmetric values).

KaiB can bind to the inactive form of KaiC. The resulting KaiB–KaiC complex can then bind to and sequester KaiA. The phosphorylation behavior of KaiC in the presence of KaiB, but not KaiA, is essentially identical to that of KaiC in the absence of both KaiA and KaiB (11, 12). This observation strongly suggests that KaiB does not directly affect phosphorylation and dephosphorylation rates. We propose instead the following functions for KaiB. (i) KaiB can increase the stability of the inactive state of KaiC by binding to it. This restores the capacity of individual KaiC hexamers to sustain phosphorylation cycles. (ii) Strong binding of KaiA by KaiB associated with the inactive KaiC hexamers reduces the concentration of free KaiA dimers. This leads to a variant of the differential affinity mechanism, which is necessary for synchronizing the oscillations of the different KaiC hexamers, as we clarify below. Based on the measured size of the heteromultimeric complexes (6, 7), we assume that the inactive form of KaiC can bind two KaiB dimers, and that B2C̃4, B2C̃3, B2C̃2, and B2C̃1 can each bind two KaiA dimers with high affinity. Neither assumption is critical: A model in which more than two KaiB and two KaiA dimers can bind also generates oscillations.

The rate of spontaneous phosphorylation is lower than that of spontaneous dephosphorylation. The model includes spontaneous phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of both active and inactive KaiC. Because KaiC reaches a low phosphorylation level in the absence of KaiA (and KaiB) (3, 7, 11), the rate of spontaneous phosphorylation is lower than that of spontaneous dephosphorylation.

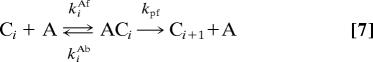

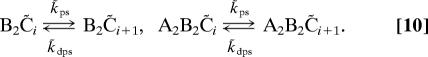

This model is described by the following reactions:

|

|

|

|

As in Synchronization with Differential Affinity above, we assume that the reaction rates are given by deterministic, mass-action kinetics. The most critical parameters are the (de)phosphorylation rates. They have not been directly measured but are strongly constrained by the large number of quantitative in vitro experiments on the subsets of Kai proteins (see below). The model's predictions are much less sensitive to the remainder of its 39 parameters; for these, we have simply chosen plausible values (see SI Appendix).

KaiA + KaiB + KaiC.

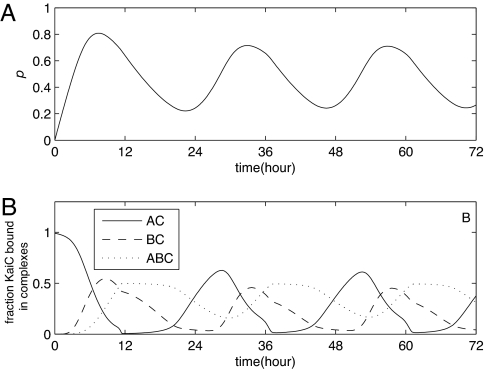

Fig. 3A shows that our model produces sustained oscillations in KaiC phosphorylation when all three Kai proteins are present in the concentrations used in ref. 7. Both the period and the amplitude of the oscillations agree well with those observed in refs. 4 and 7. Fig. 3B shows the concentrations of complexes containing KaiA and KaiC ([AC]); KaiB and KaiC ([BC]); and KaiA, KaiB, and KaiC ([ABC]), as a function of time. In the phosphorylation phase of the oscillations, KaiA binds to KaiC and stimulates its phosphorylation. At the top of the phosphorylation cycle, where KaiC hexamers flip from the active to the inactive state, KaiA is released and KaiB binds to the inactive KaiC hexamers. The binding of KaiB stabilizes the inactive form of KaiC, preventing phosphorylation by KaiA. One critical role of KaiB is thus to allow the KaiC hexamers to enter the dephosphorylation phase of the cycle.

Fig. 3.

Sustained oscillations in the full model defined by Eqs. 6–10. (A) The mean phosphorylation level p of KaiC shows a stable 24-h rhythm. (B) Kai complexes. At t = 0, KaiC is fully unphosphorylated: [C0] = [C]T; [A] = [A]T; [B] = [B]T. The average phosphorylation then increases as KaiA binds KaiC and stimulates phosphorylation. Next, the amount of KaiB–KaiC complex ([BC]) increases at high phosphorylation as KaiB binds to the inactive state of KaiC. Subsequently, KaiA is sequestered into a KaiA–KaiB–KaiC complex (ABC). The total concentrations equal those used in the in vitro experiments described in ref. 3: [C]T = 0.58 μM; [A]T = 1.75 μM; [B]T = 0.58 μM, corresponding to [A]T = [C]T and [B]T = 3[C]T. For other parameter values, see Table 2 of SI Appendix.

Fig. 3B also shows that after [BC] has increased, [ABC] increases. This is because B2C̃4–B2C̃1 can bind KaiA. This illustrates the second function of KaiB: KaiB that is bound to KaiC also sequesters KaiA. This leads to a form of the differential affinity mechanism at the end of the dephosphorylation phase of the cycle: The KaiC hexamers that are still in the inactive form (the laggards) will take away KaiA from those hexamers that have already flipped from the inactive to the active state (the front-runners). This reduces the phosphorylation rate of the front-runners, allowing the laggards to catch up.

In our model, differential affinity acts at the bottom of the dephosphorylation phase of the cycle and throughout the phosphorylation phase. From the perspective of synchronizing the oscillations of the different hexamers, the ideal would be an ever-decreasing affinity between KaiA and KaiC, even as a given hexamer passes through the same sequence of states again and again. Thermodynamics, however, dictates that the affinity of KaiA for KaiC must increase somewhere in the cycle. In our model, this happens at the top of the inactive branch, where B2C̃6 and B2C̃5 do not bind KaiA, but B2C̃4 does have a high affinity for KaiA. To obtain agreement with experiment, it is both necessary and sufficient for differential affinity to act on the inactive branch, although differential affinity on the active branch does enhance the oscillations' amplitude.

KaiA + KaiC.

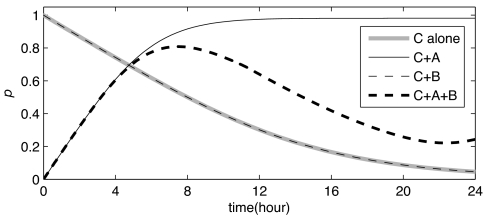

Fig. 4 shows that, in the presence of only KaiA, initially unphosphorylated KaiC reaches a phosphorylation level of ≈90–95% after 6–8 h, in good quantitative agreement with experiment (7). In our model, KaiC is biased toward the active state, and KaiA binding increases the stability of the active state even further. This explains the high steady-state phosphorylation level when only KaiA is present.

Fig. 4.

KaiC phosphorylation in the absence of KaiA and KaiB (C alone), in the presence of KaiA (C+A), in the presence of KaiB (C+B), and in the presence of both KaiA and KaiB (C+A+B). For C+A, KaiC is initially fully unphosphorylated; for C alone and C+B, KaiC is initially fully phosphorylated (see also ref. 7). Parameters are as in Fig. 3.

(KaiB +) KaiC.

Fig. 4 also shows that the phosphorylation behavior of KaiC in the presence of KaiB is very similar to that of KaiC alone, as observed (11, 12). Our model can explain this observation by assuming that the spontaneous dephosphorylation rate of the two KaiC conformations is the same and is unaffected by KaiB binding, which only stabilizes the inactive state with respect to the active one.

Temperature Compensation.

A striking feature of the in vitro oscillations of the Kai system is that they are temperature-compensated (4). Specifically, as the temperature is increased from 25°C to 35°C, the period of the oscillations decreases by only 10%. In general, the oscillation period of a network depends on the rates of all of the reactions in the system. In principle, one could try to achieve temperature compensation by balancing the temperature dependencies of all of these rates (29). We have adopted a different approach that is motivated by the fact that the (de)phosphorylation reactions are each individually temperature-compensated (3): The phosphorylation time courses of KaiC alone and of KaiC with KaiA change little between 25°C and 35°C. Indeed, the key idea of our approach is to construct the model so that the oscillation period is determined by those rates that are known from experiment to be robust against temperature variations while leaving it insensitive to the other rates, which might vary with temperature.

A natural idea is to demand that the rates that can vary with temperature be much faster than the (de)phosphorylation rates, so that the period is dominated by the latter, which are temperature-compensated. This leads to the following ingredient.

5. All (un)binding rates and the flip rates f6 and b0 are much faster than the (de)phosphorylation rates. Most conformational transitions are made at the top and bottom of the cycle; the period is thus less sensitive to flip rates other than f6 and b0.

Even when the (un)binding reactions between the Kai proteins are fast, however, the period can still depend on the ratios of their rates (the dissociation constants), which will vary with temperature. The period becomes independent of the dissociation constants if all binding reactions go to completion. This occurs when the dissociation constants are much smaller than typical protein concentrations; in this limit, a change in the dissociation constants will have no appreciable effect on the fraction of bound proteins. We thus require the following.

6. The affinities among the Kai proteins are high. KaiA, the least abundant of the three proteins, will then be almost entirely bound up in complexes with KaiB and KaiC, in agreement with ref. 7. As long as the relative magnitudes of the dissociation constants do not change with temperature, the composition of these complexes will moreover be unaffected. The phosphorylation rates, which depend on [ACi], are then robust to changes in temperature. Another important consequence of this condition is that a proportional increase in all of the protein concentrations will have no effect on the oscillations, as has been observed (7).

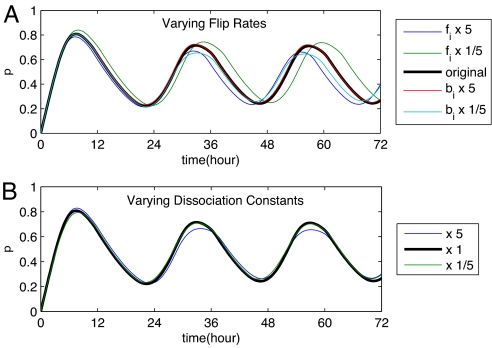

Because no data on the temperature dependence of the dissociation constants and flip rates exists, we made the following estimate. We assumed that both the binding energies and the energy barriers for the conformational transitions are at most 50 kBT. If the temperature is changed from 25°C to 35°C, the dissociation constants and flip rates can then change by about an order of magnitude. To test whether our model is robust against such perturbations, we have varied both dissociation constants and flip rates by a factor of 5 in each direction. Fig. 5 shows that our model withstands these trials: The period varies by ≈5–10%, in very good agreement with the experiment described in ref. 4. This is strong evidence that conditions 5 and 6, together with temperature-compensated (de)phosphorylation rates, are sufficient for temperature-compensated oscillations.

Fig. 5.

Temperature-compensated oscillation period. The period of KaiC phosphorylation changes by 10% when the forward (fi) or backward (bi) flip rates are changed by a factor 25 (A) and by <5% when the dissociation constants for all KaiA and KaiB binding reactions are simultaneously changed by a factor 25 (B). Parameters are as in Fig. 3.

KaiC Dynamics as a Function of KaiA and KaiB Concentration.

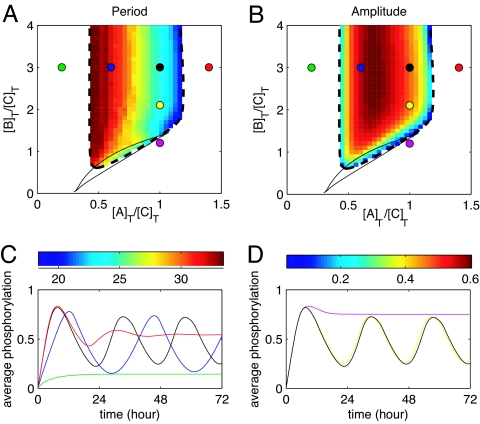

Fig. 6 shows the behavior of our model as a function of the total KaiA and KaiB concentrations [A]T and [B]T. For [A]T ≲ 0.5[C]T, the system exhibits no oscillations. At around [A]T = 0.5[C]T, the system starts to oscillate via a supercritical Hopf bifurcation with a period of ≈35 h (see SI Appendix for details on the bifurcation analysis). As the KaiA concentration is increased, the period monotonically decreases. In contrast, the amplitude first increases to reach a maximum at around [A]T = 0.85[C]T, then decreases until oscillations disappear at around [A]T = 1.25[C]T. The dynamics as a function of the KaiB concentration are markedly different. Fig. 6 shows that a minimum KaiB concentration of about [B]T = [C]T is needed to sustain oscillations. Above that threshold, neither the period nor the amplitude depend strongly on [B]T.

Fig. 6.

KaiC oscillations as a function of KaiA and KaiB concentration. (A and B) Period (A) and amplitude (B) of oscillations in KaiC phosphorylation as a function of the concentration of KaiA and KaiB. The dashed curve shows the location of the supercritical Hopf bifurcation that gives birth to the oscillations, and the color scales give period in hours and amplitude of p oscillation. Note the appearance of a small region of bistability (solid line; see also SI Appendix) at low [A]T and [B]T. The remaining parameters are as in Fig. 3. (C) KaiC oscillations as a function of KaiA concentration. Results are shown for [B]T = 3[C]T and [A]T = 0.2[C]T (green), 0.6[C]T (blue), [C]T (black), and 1.4[C]T (red). (D) KaiC oscillations as a function of KaiB concentration. Results are shown for [A]T = [C]T and [B]T = 1.2[C]T (purple), 2.1 [C]T (yellow), and 3[C]T (black).

The different effects of varying [A]T and [B]T can be understood from the different roles the two dimers play in our model. KaiA stimulates the phosphorylation of KaiC. If the total KaiA concentration is very low, the phosphorylation rate will thus be so slow that it is counterbalanced by the spontaneous dephosphorylation rate. If, on the other hand, the total KaiA concentration is very high, the mechanism of differential affinity no longer functions, because it relies on competition for a limited amount of KaiA. The function of KaiB is to stabilize inactive KaiC and to sequester KaiA. As long as enough KaiB is available to perform these functions, the period and amplitude will not depend on the KaiB concentration.

Interestingly, the very recent experiments described in ref. 7 give strong support for our model. In particular, these experiments show that when the KaiA and KaiB concentrations are reduced from their standard values by a factor of 4 and 3, respectively, all oscillations cease in very good agreement with our results. We further predict that there is an upper bound on the KaiA concentration, but not on the KaiB concentration, for oscillations to exist. Moreover, although the amplitude and the period of the oscillations do not depend in our model on [B]T, they do depend in a very specific manner on [A]T. These dependencies on the KaiA and KaiB concentrations are direct consequences of the basic roles of these proteins in our model. They thus represent some of our most robust and important predictions.

Discussion

We have presented an allosteric model of KaiC phosphorylation that can describe a wealth of experimental data on the Kai system. Its foundation is the assumption that each KaiC hexamer can exist in two distinct conformational states, an active one in which it tends to be phosphorylated and an inactive one in which it tends to be dephosphorylated. Because of the interplay between nucleotide binding, which favors the active state, and phosphorylation, which favors the inactive state, each individual hexamer will repetitively gain and lose phosphate groups. However, if macroscopic oscillations are to be observed, the phosphorylation cycles of the individual hexamers must be synchronized. We introduced a mechanism, called differential affinity, which, in contrast to some previous models (19, 20), allows for synchronization even in the absence of direct interactions between hexamers. The key idea is that although all KaiC hexamers compete to bind KaiA, which stimulates phosphorylation, the laggards in the cycle are continuously being favored in the competition. This mechanism is most effective when KaiB and KaiC bind KaiA very strongly. It is also precisely in this limit that the oscillation period becomes insensitive to changes in the Kai proteins' affinities for each other. Differential affinity and temperature compensation are thus intimately connected. The mechanism of driving two-body reactions to saturation is, however, more general; it could, for instance, be used to make temporal programs of gene expression robust against temperature variation (30).

In S. elongatus, the concentration of KaiA dimers is <10% of that of KaiC hexamers (12). Our model predicts that in this regime, the in vitro oscillations of ref. 4 disappear. The very recent experiments described in ref. 7 support this prediction: They unambiguously demonstrate that in vitro, the oscillations cease to exist if the concentration of the KaiA dimers is <25% of that of the KaiC hexamers. Clearly, in vivo, other processes are at work. It is known, for instance, that both the subcellular localization of the Kai proteins (12) and KaiC's role as a transcriptional repressor (5) affect circadian rhythms, as do other clock proteins such as SasA (6). It is tempting to speculate, however, that these additional effects merely shift the phase boundaries of the model presented here without changing its basic mechanism. One could imagine, for example, that a combination of KaiB localization to the cell membrane and competitive binding by molecules like SasA could reduce the number of sites available to sequester KaiA, thus allowing the oscillator to function at lower KaiA concentrations.

Finally, our model makes a number of predictions that could be verified experimentally. One clear prediction is that KaiC can exist in two distinct conformational states. Moreover, our model suggests that KaiC binds KaiA and KaiB very strongly, with dissociation constants that depend on the conformational state and phosphorylation level of the KaiC hexamer. But perhaps the strongest test of our model concerns the KaiC oscillation dynamics as a function of the KaiA and KaiB concentrations (see Fig. 6): We predict that the oscillations will disappear when the KaiA concentration is increased but not when the KaiB concentration is increased.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Daan Frenkel and Martin Howard for a critical reading of the manuscript and the Aspen Center for Physics for its hospitality to D.K.L. early in this project. The work was supported by Fundamenteel Onderzoek der Materie/Nederlandse Organisatie voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0608665104/DC1.

References

- 1.Ishiura M, Kutsuna S, Aoki S, Iwasaki H, Andersson CR, Johnson CH, Golden SS, Kondo T. Science. 1998;281:1519–1523. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5382.1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dunlap JC, Loros JJ, DeCoursey PJ. Chronobiology: Biological Timekeeping. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tomita J, Nakajima M, Kondo T, Iwasaki H. Science. 2005;307:251–254. doi: 10.1126/science.1102540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakajima M, Imai K, Ito H, Nishiwaki T, Murayama Y, Iwasaki H, Oyama T, Kondo T. Science. 2005;308:414–415. doi: 10.1126/science.1108451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakahira Y, Katayama M, Miyashita H, Kutsuna S, Iwasaki H, Oyama T, Kondo T. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;101:881–885. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307411100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kageyama H, Kondo T, Iwasaki H. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:2388–2395. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208899200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kageyama H, Nishiwaki T, Nakajima M, Iwasaki H, Oyama T, Kondo T. Mol Cell. 2006;23:161–171. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hitomi K, Oyama T, Han S, Arvai AS, Getzoff ED. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:19127–19135. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411284200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nishiwaki T, Iwasaki H, Ishiura M, Kondo T. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:495–499. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.1.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iwasaki H, Nishiwaki T, Kitayama Y, Nakajima M, Kondo T. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:15788–15793. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222467299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu Y, Mori T, Johnson CH. EMBO J. 2003;22:2117–2126. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kitayama Y, Iwasaki H, Nishiwaki T, Kondo T. EMBO J. 2003;22:2127–2134. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nishiwaki T, Satomi Y, Nakajima M, Lee C, Kiyohara R, Kageyama H, Kitayama Y, Temamoto M, Yamaguchi A, Hijikata A, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:13927–13932. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403906101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayashi F, Itoh N, Uzumaki T, Iwase R, Tsuchiya Y, Yamakawa H, Morishita M, Onai K, Itoh S, Ishiura M. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:52331–52337. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406604200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayashi F, Ito H, Fujita M, Iwase R, Uzumaki T, Ishiura M. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;316:195–202. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams SB, Vakonakis I, Golden SS, LiWang AC. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:15357–15362. doi: 10.1073/pnas.232517099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iwasaki H, Taniguchi Y, Ishiura M, Kondo T. EMBO J. 1999;18:1137–1145. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.5.1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldbeter A. Biochemical Oscillations and Cellular Rhythms: The Molecular Bases of Periodic and Chaotic Behaviour. New York: Cambridge Univ Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Emberly E, Wingreen NS. Phys Rev Lett. 2006;96:038303. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.96.038303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mehra A, Hong CI, Shi M, Loros JJ, Dunlap JC, Ruoff P. PLoS Comput Biol. 2006;2:e96. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kurosawa G, Aihara K, Iwasa Y. Biophys J. 2006;91:2015–2023. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.076554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang J. J Struct Biol. 2004;148:259–267. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bell CE. Mol Microbiol. 2005;58:358–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nishiwaki T, Satomi Y, Nakajima M, Lee C, Kiyohara R, Kageyama H, Kitayama Y, Temamoto M, Yamaguchi A, Hijikata A, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:13927–13932. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403906101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu Y, Mori T, Pattanayek R, Pattanayek S, Egli M, Johnson CH. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:13933–13938. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404768101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Monod J, Wyman J, Changeux J-P. J Mol Biol. 1965;12:88–118. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(65)80285-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gillespie DT. J Phys Chem. 1977;81:2340–2361. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pattanaeyk R, Williams DR, Pattanayek S, Xu Y, Mori T, Johnson CH, Stewart PL, Egli M. EMBO J. 2006;25:2017–2028. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruoff P, Rensing L, Kommedal R, Mohsenzadeh S. Chronobiol Int. 1997;14:499–510. doi: 10.3109/07420529709001471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shen-Orr S, Milo R, Mangan S, Alon U. Nat Genet. Vol. 31. 2002. pp. 64–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.