Commencing next year, acute-care hospitals, nursing homes and other institutions will be asked to report their rates of either Clostridium difficile or methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus as part of the process for obtaining Canadian Council on Health Services Accreditation (CCHSA).

But unlike increasing numbers of hospitals in the United States, where new legislation is forcing mandatory public disclosure of nosocomial infection rates, the Canadian institutions will not have to make their numbers public.

In Canada, performance measures in the area of patient safety, including infection control, are an “integral part” of the CCHSA's new accreditation program, says President and CEO Wendy Nicklin.

“We're being asked by clients and by our stakeholders to be more specific in this area because of the priority,” says Nicklin. The CCHSA will request that all institutions seeking accreditation report on whichever infection is more pressing; C. difficile or MRSA.

Starting this year, CCHSA accreditation will be mandatory in Quebec. While not mandatory in other provinces, CCHSA accreditation is necessary for hospitals with Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada-approved residency programs.

The Council will use the information to help institutions resolve infection problems by providing them with prevention and control standards, Nicklin says, stressing that reporting infection rates is part of a quality improvement exercise, not a licensing requirement for the 923 institutions (and 3750 sites) it serves.

Although the Council encourages institutions to share their report externally, they aren't, and won't be required to do so. “It is their report to share,” Nicklin says. “We release aggregate data and information about what the survey reports have shown and trends related to the nature of the recommendations.”

By contrast, hospitals in the US will increasingly have no choice about releasing their infection information. As of February 2007, 14 US states had passed legislation requiring hospitals to publicize their rates of hospital-acquired infections. In addition, California and Rhode Island require hospitals to report on how well they are following infection control policies. Nevada and Nebraska report hospital infection rates to their respective health departments, but don't share the information with the public. Another 18 states are considering bills that would require some kind of public reporting of hospital infection rates.

Infections are one of the top 3 adverse events that patients in hospitals face, so the accreditation program is needed to improve patient safety, says Dr. Susan Brien, the Canadian Patient Safety Institute's director of operations for Quebec, Nunvaut and Atlantic Canada.

“One of the things that we know about the safety and quality business is that if you don't measure it, it doesn't change,” Brien says, arguing that once institutions begin to collect the information about infection rates, their commitment to preventing and reducing hospital-acquired infections will improve.

Although Brien thinks it's important that patients know what the infection situation is at the hospitals that serve them, she's not convinced public reporting is the best way to pass on that information. Instead, she'd like to target hospital boards and surgeons.

“I think surgeons need to know their own infection rates,” says Brien, a neurosurgeon. “As part of the standard consent process they need to disclose what the infection rates are for the patient, so the patient can make the appropriate decision.”

Hospital boards are responsible for the quality of care within their organizations, so month-to-month updates would help them track improvements in infection rates by specialties and monitor high-risk infections like C. difficile and MRSA, she says.

Once institutions know what their infection rates are, they need to communicate that widely throughout the hospital to encourage infection control procedures, like hand-washing, Brien stresses.

Concern about the prevalence and virulence of C. difficile and MRSA has been rising, particularly since the so-called Quebec strain of C. difficile was credited with causing as many as 2000 deaths. Thus far, though, only Quebec and Manitoba have made C. difficile a reportable disease, even though the move was recommended for all provinces by the Public Health Agency of Canada's National Notifiable Disease Working Group.

The Canadian Nosocomial Infection Surveillance System is surveying 48 sentinel institutions to measure the incidence of a virulent strain of C. difficile, says Shirley Paton, director of Health-Care Acquired Infections at the Public Health Agency of Canada. Thus far, it has found that the strain involved in the original Quebec outbreak has migrated to every province except PEI, which does not have a sentinel hospital. “It's obviously spread very rapidly. There's still a lot more to find out about it, like when and how the extra toxins are being produced,” Paton says.

The program has been monitoring MRSA since 1995, and has discovered that rates are rising steadily. Such developments have left the Public Health Agency increasingly concerned about the emergence of community-acquired MRSA and C. difficile, Paton says.

Canada has more to do in terms of understanding and communicating infection rates both within hospitals and in the community, she adds. Among the problems is comparing posted public data in the absence of comparable reporting standards. For instance, should hospitals report the presence of the Staph. aureus organisms, she asks, which may or may not result in outbreaks, or only report outbreaks of MRSA? Unless a standard is agreed upon, it will hard for patients to compare institutional performance, Paton says. But the Canadian Council on Health Services Accreditation's new program “is a huge first step.” — Laura Eggertson, Ottawa

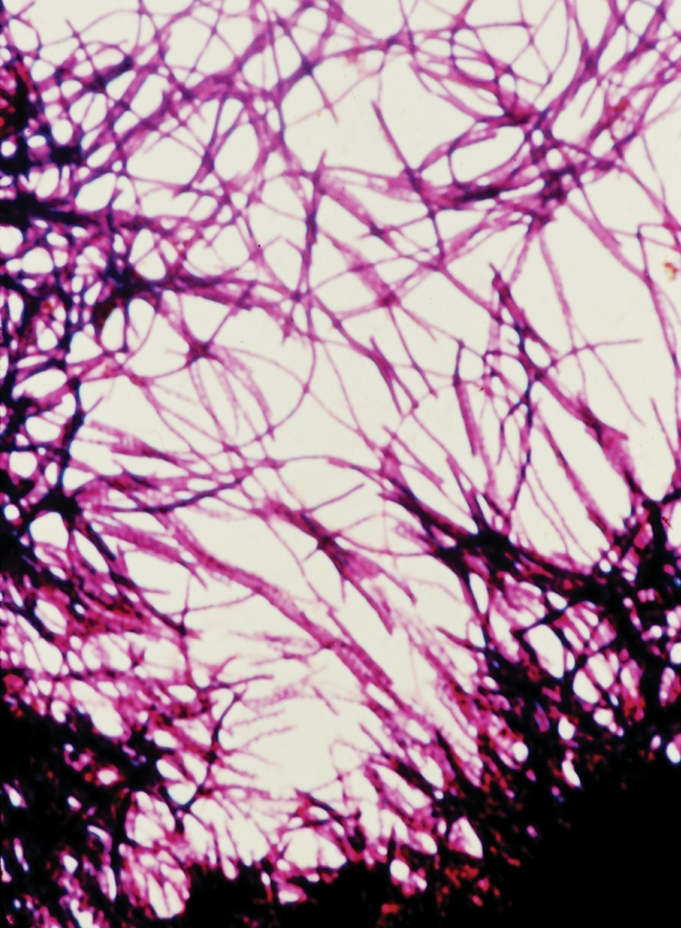

Figure. The Canadian Nosocomial Infection Surveillance System is surveying 48 sentinel institutions to measure the incidence of a virulent strain of C. difficile. Photo by: US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention