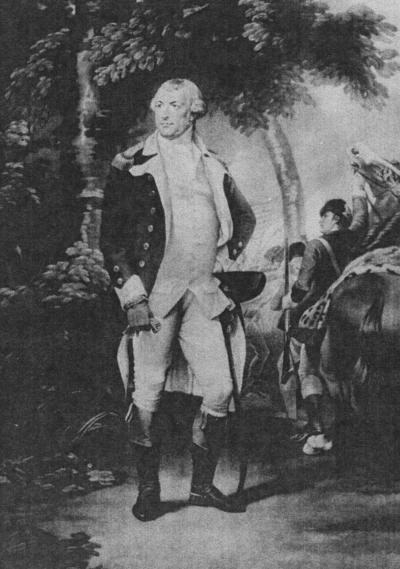

From the outset of the American War for Independence, military leaders on both sides recognized the perils of warm weather campaigning in the feverish lowcountry of South Carolina and Georgia. Yet that knowledge did not stop them from doing so. American military leaders mounted several costly and fruitless summer campaigns against British forces in Florida and Georgia. It was the British that suffered the most significant losses from the region's fevers, however, particularly during the campaign of 1780. It began well, with Sir Henry Clinton's capture of Charleston in May. Yet Clinton's southern strategy seriously undermined the health of his forces, and may have cost the British the war. To secure control over the Lower South required keeping thousands of their soldiers in what was then the unhealthiest region of British North America. Despite winning another key victory at Camden, British forces in the region sustained heavy casualties from disease in the summer and fall of 1780. In April 1781 Lord Cornwallis (Figure 1) cited saving his army from another Carolina fever season as one of the main reasons for his decision to move north to Virginia and his fateful encounter at Yorktown that October.

Fig. 1.

Earl Cornwallis, Commander of British Forces in the South, 1780–81.

With some exceptions, historians of the Revolution have either ignored or understated the influence of disease on the war in the Lower South. A few historians mention disease as an important factor in the campaigns, and others point to instances when the sickness of a particular officer or unit may have affected the outcome of an engagement.† But none have attempted to investigate the impact of disease on the conduct of the campaigns in a systematic way. Those involved in the war, however, were keenly aware of the large role sickness played in the war in the Lower South, and it is on their accounts that this paper is largely based.

Although it would be simplistic to say that disease determined the outcome of the Southern Campaign, it unquestionably affected its conduct and commanders' decisions in significant ways. Malaria and other fevers killed and incapacitated large numbers of soldiers and felled key officers and commanders at critical moments. Reading the evidence in contemporary accounts, it is hard to escape the conclusion that the microbes may have done more than the patriots to ensure an American victory.

British commanders understood the danger of campaigning in the Deep South. A few years before the Revolution, naval surgeon James Lind had written that the danger to Europeans from tropical fevers was far greater in South Carolina than in the colonies to the north, and was similar to that of the West Indies (1). Some South Carolina patriots saw the local diseases as a potential ally. In the spring of 1776, the British sent a fleet and army to seize Charleston. In late May, Richard Hutson predicted that if the British did not move against Charleston soon, the city could breathe freely at least until November, “for it would be the height of madness and folly for them to come here during” the sickly season (2).

Hutson's confidence was not entirely misplaced. The British commander, Sir Henry Clinton (Figure 2), fretted as June approached and the fleet sat off the South Carolina coast: “I had the mortification to see the sultry, unhealthy season approaching us with hasty strides, when all thoughts of military operations in the Carolinas must be given up” (3). On June 28, the British fleet under Sir Peter Parker tried to force its way into Charleston harbor, only to be repulsed by the cannon mounted in a hastily built palmetto log fort on Sullivan's Island. It was the first patriot victory of the war. After the battle, Clinton insisted on moving his troops back north as quickly as possible, even though their health was good. One of Clinton's officers reported that despite the heat they had fewer sick “than might have been expected in a country town in England” (4). But Clinton feared that his men would not remain healthy long in the Carolina climate” (5). His fears were justified. In late September, Hutson wrote a friend that the summer in Charleston had been “very sickly, and the mortality unusually great so early in the season” (6).

Fig. 2.

Sir Henry Clinton, British Commander in America. The Southern Strategy that began with Siege of Charleston was Clinton's Idea.

The patriots did not share Clinton's fear of fevers, at least not to the same extent. True, some of their commanders, such as Gen. William Moultrie (Figure 3) hero of the Battle of Sullivan's Island, cautioned against the perils of warm weather campaigning in the Southern lowcountry. But others insisted on pursuing offensive operations during the sickly months. Patriots in the Carolinas and Georgia tried to attack British Florida in the summers of 1776 and 1778, but in both cases suffered heavy casualties from fevers virtually without firing a shot at the British (7–11).

Fig. 3.

Gen. William Moultrie of South Carolina.

Following the failure of the second patriot campaign, the British took the offensive. Reinforced by an expedition from New York, Gen. Augustine Prevost captured Savannah in December 1778. In the spring of 1779 he moved part of his army north and briefly threatened Charleston before retreating to Georgia. Prevost withdrew in the face of two enemies: a larger patriot force under Gen. Benjamin Lincoln (Figure 4) and the advancing sickly season (2,3). Lincoln's army followed Prevost south as far as the Savannah River, but both armies suspended major operations during July and August (14). Prevost told Clinton that his own poor health, weakened by seven years in hot climates, was largely to blame for his failure to capture Charleston, and predicted that the city would fall easily to “four thousand effective British troops” (15).

Fig. 4.

Gen. Benjamin Lincoln, Patriot Commander, Charleston, 1779–80.

Prevost's troops were far from effective in the summer of 1779. When he returned to Savannah in mid-July, he found the men he had left behind to protect Georgia were suffering from widespread sickness. He soon found himself forced to defend Savannah against an assault by combined American and French forces. Despite being badly outnumbered, the British repulsed their attackers with heavy losses. But they lost one of their most talented officers, Col. John Maitland, to a “bilious fever,” probably malaria. Maitland's death was a serious blow for the British. One historian has argued that the southern campaign might have taken a different course “had this exceedingly capable officer lived” (16).

Prevost's incursion into South Carolina in 1779 accomplished little beyond infuriating the patriots, but it was strategically significant. It convinced Clinton and the home government that the southern strategy could win the war. He agreed with Prevost that the town could be captured without great difficulty. Clinton believed that if he could seize Charleston, he could gain control of the Carolinas and draw on the strong loyalist support in that region. But he was determined that the operation should take place during the healthy season. At his insistence, the expedition that captured Savannah had taken place in the late fall and early winter. In the case of Charleston, he intended to leave New York in late September and arrive in South Carolina in early October. Had this happened, the British would have had about eight relatively healthy months in which to secure the Carolinas. But several unforeseen developments delayed his departure. As a result, the expedition did not leave for South Carolina until December 24. The voyage south was unusually long and stormy and the expedition did not land in South Carolina until February 11, four months later than Clinton had planned. Those four months may have cost the British the war (17).

Prevost joined Clinton with part of his army from Savannah, and soon the British had Charleston surrounded by 11,000 men (18). The defenders held out until May 11, when Lincoln accepted Clinton's terms. It was the greatest British victory of the war to that point, and cause for great celebration at home. One observer predicted that it would lead to “the submission of the Carolinas and maybe some other Provinces and terminate the rebellion ere the year is finished.” He added that he had “feared the heats and the many other events that frequently defeat the best connected measures” (19). Despite his late start, Clinton had beaten the “heats” to capture Charleston, and he apparently also believed that the Carolinas would quickly come to heel. He returned to New York in June with about a third of the army, leaving Lord Cornwallis to finish the job. But given his earlier concerns about the climate, it is hard to see how Clinton could have been complacent about leaving thousands of troops in the southern lowcountry with the sickly season rapidly approaching (20).

The city and its hinterland were in prime condition for the spread of epidemics. The region had suffered badly from the siege and years of privation and stagnant trade. Many of the formerly wealthy inhabitants were reduced to penury, and the poor and blacks to utter destitution (21). Charleston was extremely filthy in the wake of the siege, and remained so for months, partly due to hygienic carelessness on the part of the soldiers (22). Health conditions in the town and surrounding area deteriorated through the summer and into the fall. Large numbers of American prisoners, especially those on the filthy prison ships, died of smallpox and fevers, which may have included yellow fever as well as malaria, and typhus or typhoid (23,24). Thousands of slaves were fleeing to the British lines in hopes of freedom, and by mid-July a malignant fever and smallpox was killing large numbers of them (25,26). In February 1781, planter William Burrows wrote that Charleston and its hinterland had been sickly all the previous year, and he had never been more ill in his life. He had lost thirty slaves to smallpox, and was in danger of losing seven more (27).

Partisans and Pestilence: Summer and Fall of 1780

According to one official report, the British army remained “reasonably” healthy in mid-July (28). But if so, their health quickly deteriorated after that time and they remained sickly throughout the fall (29). The spread of diseases was facilitated by the constant movement of British soldiers and camp followers to and from the lowcountry. Following the surrender of Charleston, the British quickly moved forces inland to secure control and recruit soldiers over the interior of South Carolina, with the intention of doing the same in North Carolina. Neither goal was accomplished. Harsh British policies and actions towards the inhabitants were partly to blame for this outcome. The region contained substantial numbers of Loyalists, but there were also many people who were not committed to either side; they simply desired to be left alone. The British alienated many of these people by heavy-handed attempts to force men to take loyalty oaths and then fight for the Crown. Allegations of British and Loyalist brutality also tarnished their cause, although both sides behaved atrociously at times (30,31).

For all their blundering, the British might well have succeeded in their southern strategy had it not been for the diseases that weakened their army (32). The garrison at Charleston became increasingly sickly throughout the fall, with the Hessians suffering especially heavily (33). According to Surgeon Robert Jackson, the most common illnesses Cornwallis's army suffered in 1780 were “intermittents,” probably vivax malaria. But he also noted the presence of more deadly malignant fevers, probably falciparum malaria or perhaps yellow fever. Some contemporaries also reported the presence of breakbone (dengue) fever in the region. Dysentery was also a problem. But the most commonly used terms in the British correspondence relating to the soldiers' sickness are “intermittents,” “agues and fevers,” “malignant fevers,” “putrid fevers,” and “bilious fevers,” all of which point to malaria and perhaps yellow fever and/or typhus (34). In combating disease, the British everywhere were hampered by inadequate medical facilities, supplies, and personnel. The personnel problems were increased by widespread illness among the British surgeons, including the chief surgeon, John McNamara Hayes. In November, most of the surgeon's mates in Charleston were sent back to Britain because they were too ill to continue working (35).

The situation in Savannah was much the same as in Charleston. Its commander, Lt. Col Alured Clarke, reported in early July that the heat and sickness was “beyond anything you can conceive.” By late August, his force was so depleted by sickness that he was begging for reinforcements from South Carolina. In early October, Clarke reported to Cornwallis, “Our suffering from sickness in this vile climate is terrible and continues in a very great degree.” He had been “extremely ill” himself. A Hessian regiment had lost “many men and some officers, and at present has not really above sixty men fit for duty” (36,37).

In August, Cornwallis wrote Clinton that his efforts to subdue the South Carolina lowcountry were hindered not only by the rebelliousness of the people but by the “terrible climate, which except in Charleston, is so bad within an hundred miles of the coast, from the end of June to the middle of October, that troops could not be stationed among them during that period without a certainty of their being rendered useless for some time for military service, if not entirely lost.” An indication of the seriousness of the problem was that even local loyalists were eager to abandon the malarious country for Charleston during the summer: “our principal friends,” he wrote, “are extremely unwilling to remain in the country during that period, to assist forming the militia and establishing some kind of government” (38). From Georgetown, Maj. Wemyss wrote on July 29, that his men were “falling down very fast” with intermitting fevers. A few days later, he reported that 6 men had died of putrid fevers within the past three days and 30 other men were ill (39). On July 30, Cornwallis ordered Wemyss to leave Georgetown, where he was having little success in recruiting men for the militia, and move inland along the Black River. He cautioned him not to stay long in any place along the river, “which is a very sickly country” and to move by “short and easy marches” to encamp in the High Hills of Santee, an area reputedly much healthier (40).

The British leaders were not unduly surprised by the unhealthiness of the lowcountry. They knew its reputation. But they did not expect to find similar conditions in the upper part of the state, which many writers had commended for its healthy climate. As they moved into the upcountry, they expected to have the aid of better health and a large body of loyalists. Both expectations were rudely shattered. They found far more rebels and a far unhealthier situation than they had been led to believe. It is difficult to determine which was the more shocking, but disease, particularly malaria, reduced British fighting capacity more effectively than patriot bullets. From nearly every outpost and detachment in upcountry South Carolina and Georgia, Cornwallis received similar tales throughout the summer and fall: widespread and sometimes deadly sickness was felling officers and men. Lt. Col. Balfour wrote Cornwallis on July 17 that “we are turning sickly fast and our surgeon [is] very ill” (41). The main body of the British army, camped in and near Camden under Lord Rawdon (Figure 5), was also suffering. On August 1, Rawdon reported that he had sent many of his men to posts outside the town to what he believed were healthier locations. He had himself suffered a “severe attack of the ague” (42). Cornwallis had picked Camden as a site for the main army partly because “for this country, [it] is reckoned a tolerably healthy place” where the troops could also be conveniently supplied from Charleston. On July 25, Cornwallis received a request from the officers of the provincial regiments to recruit in Carolina because their detachments had been so depleted by disease (43).

Fig. 5.

Francis, Lord Rawdon, Cornwallis's Second-in-Command.

Perhaps no British unit was more reduced by fevers than the 71st (Highland) regiment, and in no case were the consequences more serious for the British. During June, Cornwallis posted the 71st to Cheraw Hill east of Camden, which had “the appearance of being healthy, but it proved so much the contrary and sickness came on so rapidly” that during July two-thirds of them were seized with “fevers and agues and rendered unfit for service” (44). The ill officers included their commander, Maj. Archibald McArthur (45).

McArthur remained at Cheraw longer than Cornwallis intended him to, because he believed it to be both secure and strategically important. But on July 24 he “found it absolutely necessary to move” his men because of the fevers. McArthur's move had serious political repercussions. Patriot leaders represented it as a retreat and a sign of weakness. In its wake, many people in the Peedee and Black River region took up arms against the British. Some local men who had joined the loyalist militia switched sides and helped to capture about 100 sick Highlanders McArthur had sent down the Peedee to get medical care in Georgetown. The capture of McArthur's men caused Cornwallis great alarm. He called it a “disaster” (46). A few days later, the patriot General Thomas Sumter captured about seventy more prisoners from Ninety Six, many of them sick (47). By early August, Cornwallis reported, the whole region was “in an absolute state of rebellion” (48).

Shortly after these events, Cornwallis, who was still in Charleston, learned that a large patriot army under Gen. Horatio Gate (Figure 6) was advancing south from Virginia. He rushed to Camden to find that about one-third of the British and Loyalist regulars were too ill to fight. The returns of August 13 show about 2000 men fit for duty, perhaps 1400 of them regulars, and over 800 sick. But according to one British officer, the whole army “was extremely sickly” when it went into battle. The 71st regiment was in the worst condition, with only 230 of their 700 men able to fight. Cornwallis believed that Gates had about 7000 men, although it was probably only a little over 3000. Under these conditions, Cornwallis might have retreated, but he decided to fight, and he later wrote that the sickness in his army actually encouraged him to do so. To retreat to Charleston, he later argued, would have required leaving many of the sick to be captured by the enemy, along with magazines and supplies, with the probable loss of most of the state to the rebels (49).

Fig. 6.

Gen. Horatio Gates, American Commander at Camden.

As it turned out, Cornwallis won a crushing victory at Camden, as the patriots retreated in disarray, and hundreds were killed or captured. But the battle did not solve his two key problems: the partisan rising and the sickness in his army. A few days after the battle, he informed Clinton that his army's “sickness was very great, and truly alarming.” His officers were especially hard-hit, and the head surgeon and almost all of his assistants were ill: “Every member of my family, and every public officer is now incapable of doing his duty” (50). To Balfour, he confided that if his men did not get healthier, it would be impossible to accomplish anything. But the troops did not get healthier for months. The 63d regiment arrived in Camden a few days later from the High Hills of Santee in a “very sickly state” and unfit for active duty. In one unit, nearly half the men had died. The 71st regiment remained largely incapacitated by fevers (51). The situation was complicated by the large number of prisoners from Gates' army captured in battle. Cornwallis decided to move them to Charleston as quickly as possible because Camden was “so crowded, and so sickly, I was afraid that the close place in which we were obliged to confine them might produce some pestilential fever during the excessive hot weather” (52). That Cornwallis was not exaggerating the direness of the situation is indicated by a letter from Eliza Pinckney to her son Thomas—a wounded prisoner—that she wished him “out of so sickly a place as Camden” (53).

Cornwallis wanted to get his own men out of sickly Camden, as well. Although he dreaded “the convalescents not being able to march,” he was advised that a move of forty or fifty miles northwest to the Waxhaws region would put the army “in a much better climate.” From there, after a few days, he hoped to march on into North Carolina to capitalize on his recent victory and rouse the Loyalists there (54). In early September, he marched the bulk of the army to the Waxhaws, leaving hundreds of sick behind in Camden. Some of the healthy troops left there also soon became sick with fevers or smallpox (55). At first, Cornwallis was pleased by his new location: “We have a pleasant camp, hilly and pretty open, dry ground, excellent water and plenty of provisions, and if that will not keep us from falling sick I shall despair” (56). Soon, he began to sound desperate: “the great sickness of the army” did not relent. Soon after his arrival at the Waxhaws, he had so many men still sick he decided that he would have to remain longer than he had hoped to allow them to recover. But while they sat, more men became sick in the new camp (57). He kept hoping that a different topography or the approaching cool weather would solve the sickness problem. In late September, he informed Clinton that the army's sickness had been increasing all month. Many men of the 71st were still in Camden, too weak to march to the new camp. The 63d was “so totally demolished by sickness that it will not be fit for actual service for some months.” As the weather was now growing cooler he hoped that would produce a “favorable change” (58).

But the army's sickliness continued into the late fall. Many men suffered relapses of their fevers and the new cases of fever were more severe than before (59). Cornwallis grew increasingly frustrated. No matter where he moved his army, fevers accompanied them: “They say go 40 or 50 miles farther and you will be healthy. It was the same language before we left Camden. There is no trusting to such experiments.” What he did not realize is that the problem was not so much the unhealthiness of the climate as the microorganisms in the bodies of his men. Wherever they moved, they took their diseases with them, and in the case of malaria and other mosquito borne fevers, all that was needed was the vectors to transmit them from one man to another. The only solution was what one colonial officer called “Good Doctor Frost.”

The continuing sickness in his army greatly delayed Cornwallis's intended advance into North Carolina, where he hoped to rouse Loyalists there and smash the patriot militias before they had time to regroup. One of his biggest headaches was securing sufficient wagons to move the large number of soldiers who were too ill to march (60). Before he moved his army into North Carolina, Cornwallis wanted to establish a post at Charlotte, where he believed he could secure needed provisions, especially wheat, as he was informed that his sick could not stomach the local corn meal. But renewed sickness once again thwarted him. He ordered Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton (Figure 7), commander of the cavalry of the British Legion, to reconnoiter and rid the army's route of hostile forces. But after thinking that Tarleton had gone, Cornwallis learned that he was prostrated by a severe fever at Fishing Creek. Cornwallis was almost frantic at the news and asked for constant updates on Tarleton's condition. He also feared that Tarleton might be captured, which would be an enormous propaganda victory for the enemy. Tarleton's cavalry was in a dangerously exposed position, without infantry support, more then twenty miles from the main army. Cornwallis wanted to move up to support Tarleton; but to do so would require abandoning the Waxhaws to the enemy and leaving some of his sick, which were “so numerous” he did not have enough wagons to move them. In addition, all the captains of Tarleton's Legion, and all but one officer of the cavalry in general was sick (61).

Fig. 7.

Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton, Commander of British Legion.

Tarleton was Cornwallis's eyes and ears, and one of his most vigorous and feared commanders. But he could not be moved, and Cornwallis hesitated to send the Legion without him, lest he risk his capture by the enemy. To Balfour, he wrote that Tarleton's illness was “of the greatest inconvenience to me at present, as I not only lose his services but the whole corps must remain quite useless in order to protect him. I do not think I can move to Charlotte without the greatest difficulty unless the Legion can advance to clear the country of all the parties who would certainly infest our rear” (62). Finally, on September 22, Tarleton was moved to a safer location, and Cornwallis ordered an advance guard of the Legion under Maj. George Hanger (Figure 8) to secure Charlotte. As they entered the town on Sept. 24, the British met fierce resistance from rebel militia. Cornwallis had to order the infantry to disperse an enemy the cavalry should have handled easily. Worse, shortly afterwards, Hanger and five other Legion officers were prostrated by a malignant fever, which Hanger later claimed was yellow fever. He also claimed it was the same disease that had struck Tarleton. Yellow fever may seem an unlikely diagnosis, given the army's distance from the coast and dense settlements where the disease normally became epidemic. But it is not impossible, when one considers that armies are highly dense communities, and the British were supplied and reinforced via river transport from Charleston and Georgetown. Aedes aegypti mosquitoes are poor fliers but excellent sailors and yellow fever moved inland via river traffic on numerous occasions in the nineteenth century. Whatever it was, the disease was highly virulent. The other officers died within a week, and Hanger barely survived, his health so shattered he was sent first to Charleston, then to Bermuda to recover, and finally back to Britain. Hanger later wrote that only those who had experienced “the miseries of ill health…in those intensely hot and sickly climates” could understand their “baneful influence” (63).

Fig. 8.

Maj. George Hanger of the British Legion.

By the time the British entered Charlotte, Tarleton was recovering, but he remained too ill to ride for several weeks. His continuing sickness helped the patriots to gain one of their most important victories. On October 7, Col. Isaac Shelby's “Over Mountain Men” destroyed a Loyalist force under Col. Patrick Ferguson at King's Mountain west of Charlotte. Cornwallis had been fretting about Ferguson's exposed position for days. He warned Ferguson about his danger and ordered him to retire if he felt at all threatened. He also requested Tarleton to go to Ferguson's aid, but Tarleton replied that he was too ill to ride. Again, Cornwallis was reluctant to send the Legion without Tarleton in command. Their performance under Hanger at Charlotte had convinced him that the Legion “are different when Tarleton is present or absent” (64). After the war, Tarleton blamed Cornwallis for the defeat, by not sending Ferguson reinforcements. After reading Tarleton's account, Cornwallis protested, “My not sending relief to Col. Ferguson…was owing to Tarleton himself: he pleaded illness from a fever, and refused to make the attempt, although I used the most earnest entreaties” (65).

But there may have been another reason for Cornwallis's failure to reinforce Ferguson and for the chaos that followed. When Cornwallis learned of the defeat at King's Mountain on Oct. 9, he, too, was down with a fever, and he may not have been thinking clearly during this critical time (66). He remained severely ill for much of the rest of the month, leaving a leadership vacuum (67,68). For more than two weeks, he was unable to write and sometimes unable to move (69). After Cornwallis had recovered in late October, Balfour wrote to him that they never knew how dangerously ill he was until he had nearly recovered (70).

A few days after King's Mountain, Cornwallis called in his exposed detachments, and ordered the army to move back to Winnsboro, South Carolina, to regroup. Reeling from attacks by partisans and fevers, the British army which seemed invincible a few weeks before, was stopped in its tracks and rolled back. The retreat from Charlotte was chaotic, and the troops suffered terribly. It rained constantly for several days, and they had no tents and very little rum, which many doctors considered a requisite in unhealthy tropical climates (71). Disease continued to haunt the army. Smallpox struck the blacks working on the defenses of Camden; many died or fled (72). The 7th regiment was “reduced to nothing by sickness” (73). Lt. Col. Turnbull asked to be relieved of his command at Camden, claiming his health had suffered so much that “I do believe that nothing but a northern climate will reestablish it, nor do I believe that ever my constitution will bear much service in this southern climate” (74). Sickness also played havoc with communications. On one occasion, a letter from Rawdon to Cornwallis was never delivered because the man who was ordered to take it became ill and failed to inform the commander or give it to someone else (75).

During November, the army's health finally began to improve. Cornwallis found Winnsboro to be “a healthy spot.” What made it healthy, of course, was the onset of colder weather. Cornwallis wrote Clinton he would remain there until he was joined by reinforcements under General Alexander Leslie. Things were improving in Charleston as well. The chief medical officer informed Cornwallis that “health once more begins to shine upon us” (76). But the effects of the fevers lingered in some cases into the colder months, as soldiers suffered relapses or long periods of convalescence (77). As late as the middle of December, Rawdon reported that he was unable to send a trusted officer on a mission to attack Gen. Francis Marion because he had “not yet conquered his ague” (78). In a letter to Lord George Germain in December, Patrick Tonyn, the royal governor of British East Florida, effectively summed up the campaign of 1780 in the Lower South when he wrote, “sickness and disease have made more havoc in the neighboring colonies than the sword” (79).

In January 1781, with his men rested and reinforced by 2000 soldiers brought by Gen. Leslie, Cornwallis resumed his march into North Carolina (80). In March he defeated a larger patriot army under Nathanael Greene (Figure 9) at Guilford Court House. But once again, victory did not solve Cornwallis's key problems. Greene's army remained intact and the country hostile. Cornwallis's army had sustained heavy casualties, and was exhausted and short of supplies. Sickness, wounds, desertion, and losses at Guilford had reduced it to about 1500 effectives. He decided to retreat southeast to Wilmington on the coast to get reinforcements and supplies. He arrived there in early April. Meanwhile, Greene moved behind him into South Carolina to attack Lord Rawdon's force at Camden.

Fig. 9.

Gen. Nathanael Greene, Commander of American Army in the South after Camden.

Cornwallis now faced a major decision. Should he return to South Carolina to help Rawdon or go elsewhere? He wrote Clinton on April 10 that he thought it best to move north into Virginia, and link up with a British army corps there. He argued that he was too far away to reach Rawdon in time and that the Carolinas could be subdued only when Virginia was securely under British control. But he gave another major reason for his preference: only by moving north could he “hope to preserve the troops, from the fatal sickness, which so nearly ruined the army last autumn” (81). No doubt Cornwallis was concerned about preserving his own health, too, after having experienced such a close call in the fall. Perhaps he recalled the words of Balfour at the time, who had rejoiced that the approaching healthy season would remove from him the danger of fever, but added “if fortune puts you another summer in this climate more care will be absolutely necessary for your health” (82).

On April 25 Cornwallis began the march north that was to lead to his fateful encounter at Yorktown in October. Fighting continued in South Carolina for two more warm seasons, producing immense suffering for both armies and the civilian population, and fevers were responsible for much of it (83). After the British evacuated Charleston in December 1782, the fighting ceased, but the American commander in South Carolina, Nathanael Greene, was ordered to keep his army intact until a peace treaty had been signed. That came in April 1783, but by then, Greene's army was on the verge of mutiny, with many of the northern soldiers threatening to desert rather than spend another fever season in the lowcountry. One of his officers had written him that nothing was “more dreadful to the soldiers than the thoughts of continuing in this country another autumn.” He declared that many of them would rather face the risks of a military court than those of “this destructive climate” (84).

We should give the last word to Henry Clinton, whose concerns about campaigning in the Lower South in the fever season proved so well-founded. In December 1781 he wrote to Lord George Germain that he expected an attack on New York or Charleston in the spring. If the attack was on Charleston, he declared, he would go there himself—“unless it takes place later than the beginning of April.” It was unfortunate for the British army that he did not feel the same concern about leaving thousands of his soldiers there in the summer of 1780 (85). Had Clinton been as careful of their health as his own, the British might not have lost their American colonies.

Footnotes

Works that emphasize the importance of disease's impact on particular aspects of the southern campaigns include Sylvia Frey, The British Soldier in the American Revolution (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1981), 42–44; Franklin and Mary Wickwire, Cornwallis: the American Adventure (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1970); Henry Lumpkin, From Savannah to Yorktown: The American Revolution in the South (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1981), 27, 39, 43, 59–61, 89, 105; Robert Bass, The Green Dragoon: The Life of Banastre Tarleton and Mary Robinson (London: Alan Redman, 1957), 106; David K. Wilson, The Southern Strategy: Britain's Conquest of South Carolina and Georgia, 1775–1780 (Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press, 2005; Elizabeth Fenn, Pox Americana: The Great Smallpox Epidemic of 1775–1782 (New York: Hill and Wang, 2001; John Pancake, This Destructive War; the British Campaign in the Carolinas, 1780–1782 (Tuscaloosa and London: University of Alabama Press, 1985), 115, 120, 235, 239.

REFERENCES

- 1.James Lind. London: 1768. An Essay on Diseases Incidental to Europeans in Hot Climates; pp. 36–37.pp. 132–33.pp. 148 [Google Scholar]

- 2.SCHS. Hutson to Isaac Hayne. Richard Hutson Letterbook, Langdon Cheves III Papers: Extracts from Private Journals. 1776. May 27, 12/99/2.

- 3.Henry Clinton. The American Rebellion. In: Willcox William B., editor. Vol. 26. New Haven: Yale University Press; 1954. pp. 28–29. (quotation) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Report of the Manuscripts of Reginald Rawdon Hastings, Esq. 3. 4 vols. London: 1776. Jul 3, Francis, Lord Rawdon to Francis, 10th Earl of Huntingdon; p. 177. 1934. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henry Clinton. The American Rebellion. In: Willcox William B., editor. New Haven: Yale University Press; 1954. p. 375. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hutson to John Godfrey. Richard Hutson Papers. 1776. Sep 26, see also, “Extracts from the Journal of Ann Manigault, 1754–1781,” SCHM 21 (1920), 113; “Letters of Thomas Pinckney, 1775–1780,” SCHM 58(1957), 72–75.

- 7.Edward McCrady. New York: The Macmillan Co.; 1902. History of South Carolina in the Revolution, 1775–1780; pp. 201–02. Charles E. Bennett and Donald R. Lennon, A Quest for Glory: Major General Robert Howe and the American Revolution (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991), 47–50. [Google Scholar]

- 8.John Fauchereau Grimke. “Journal of the Campaign to the Southward. May 9 to July 1778,”. SCHM. 1911;12:61. 190–203; William Moultrie, Memoirs of the American Revolution 2 vols. (New York, 1802), 1: 221–237; “Letters of Thomas Pinckney, 1775–1780,” SCHM 58 (1957), 155–56; Charles E. Bennett and Donald R. Lennon, A Quest for Glory: Major General Robert Howe and the American Revolution (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991), 72–82; Edward McCrady, History of South Carolina in the Revolution, 1775–1780 (New York: The Macmillan Co., 1902), 321–24; Joseph Johnson, Traditions and Reminiscences of the American Revolution in the South (Charleston, 1851), 89; H. H. Ravenel, Eliza Pinckney (New York, 1925), 272. [Google Scholar]

- 9.William Moultrie. Memoirs of the American Revolution. 1. 2 vols. New York: 1802. p. 238. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moultrie Memoirs. (1):212–20. 227, quotations on 216, 218. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moultrie Memoirs. (1):240. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robert Jackson. A Treatise on the Fevers of Jamaica with some Observations on the Intermitting Fever of America. London: 1791. pp. 90–91. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilson David K. The Southern Strategy: Britain's Conquest of South Carolina and Georgia, 1775–1780. Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press; 2005. p. 270. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Charles Stedman. The History of the Origin, Progress, and Termination of the American War. 2. 2 vols. London: 1794. p. 119. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Augustine Prevost to Sir Henry Clinton, Savannah. July 14 and July 30, 1779, Carleton Papers, PRO/30/55/17.

- 16.Augustine Prevost to Sir Henry Clinton, Savannah. July 14 and July 30, 1779, Carleton Papers, PRO 30/55/17; Sylvia Frey, The British Soldier in the American Revolution (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1981), 42–43; David K. Wilson, The Southern Strategy: Britain's Conquest of South Carolina and Georgia, 1775–1780 (Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press, 2005, parenthesis, 143–44, 176, 273.

- 17.Clinton to Lord George Germain. Germain to Clinton. 1779. Aug 21, Aug. 12, 1780, Carleton Papers, PRO 30/55/18, Clinton to Germain, Sept. 26, 1779, Germain to Clinton, Sept. 27, 1779, Clinton to Germain, Oct. 26, 1779, Carleton Papers, PRO 30/55/19; Clinton to Lord Auckland, Oct. 10, 1779, Auckland Papers, vol. 5, British Library, Add. Mss. 34416; Henry Clinton, The American Rebellion, ed. by William B. Willcox (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1954), 140–52, 426–434; David K. Wilson, The Southern Strategy: Britain's Conquest of South Carolina and Georgia, 1775–1780 (Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press, 2005, parenthesis, 71.

- 18.William Moultrie. Memoirs of the American Revolution. 2. 2 vols. New York: 1802. pp. 43–44.pp. 48–49. 55–56; David Ramsay, The History of the Revolution of South Carolina (Trenton: Collins, 1785), 2:46; Benjamin Franklin Hough, The Siege of Charleston, 1780 (Spartanburg, S.C.: The Reprint Co. 1975; originally published, Albany, N.Y., 1867), 37; David B. Mattern, Benjamin Lincoln and the American Revolution (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1995), 90; David K. Wilson, The Southern Strategy: Britain's Conquest of South Carolina and Georgia, 1775–1780 (Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press, 2005), 203–205, 218. [Google Scholar]

- 19.G. Cressener to Charles Jenkinson. Liverpool Papers, British Library, Add Mss. 1780. Jun 29, 38214.

- 20.Roger Lamb. An Original and Authentic Journal of Occurrences during the Late American War. New York: New York Times and Arno Press; 1968. p. 294. Dublin, 1809, Reprint. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Great Britain, Historical Manuscripts Commission. Report on American Manuscripts in the Royal Institution of Great Britain. 4 vols. Boston: Gregg Press; 1780. Jul 1, James Simpson to Clinton. 1972, reprint of original edition, London, 1904–09), 2: 149–50. Eliza Lucas Pinckney agreed with Simpson's assessment: “So scarce is gold and silver and such is the deplorable state of our country from two armies being in it for near two years the plantations have been some quite, some nearly ruined.” Eliza Pinckney to [?], Charleston, Sept. 25, 1780, Charles Cotesworth Pinckney Family Papers, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., 1st ser., box 5. I owe this reference to Elizabeth Fenn. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Board of Police Proceedings. 1780. Jul 7, p. 4. Jan. 5, 1781, 24L, CO5/519, National Archives, Kew.

- 23.William Moultrie. 2 vols. New York: 1802. Memoirs of the American Revolution; pp. 112–13. 2. to General Patterson, June 15, 1780. Smallpox epidemics spread throughout the state during 1780 and into 1781. James Wemyss to Cornwallis, July 11, 1780, PRO 30/11/2/269–70; Banastre Tarleton to George Turnbull, Nov. 5, 1780, PRO 30/11/4/63–64; Keating Simons to Cornwallis, Aug. 11, 1780, PRO 30/11/63/36–37; Josiah Smith, “Diary, 1780–1781,” South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine 33 (1932), 21, 113; Letters of Eliza Wilkinson arr. By Caroline Gilman (New York: 1839), 93; Uzal Johnson, Loyalist Surgeon: A Revolutionary War Diary, ed, by Bobby Gilmer Moss (Blacksburg, S,C., Scotia-Hibernia Books, 2000), 89–92; James Thacher, A Military Journal of the American Revolution (Boston: Richardson and Lord, 1823), 294, 355. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Balfour claimed that he had originally put the prisoners on ships because he lacked proper facilities and sufficient men to guard the prisoners. Balfour to Cornwallis. Oct. 22 and 29, 1780, PRO 30/11/259–60 and 309–310; Cornwallis to Clinton, Dec. 3, 1780, Carleton Papers, PRO 30/55/27; Peter Fayssoux to David Ramsay, Mar. 26, 1785, Documentary History of the American Revolution, ed. Robert Wilson Gibbes (1853–57; reprint, 3 vols. in 1, New York, 1971), 117–121, also quoted in David Ramsay, The History of the Revolution of South Carolina (Trenton, N.J., 1785), 2:527–35.

- 25.Simpson to Clinton. 1780. Jul 16, Carleton Papers, PRO 30/55/24.

- 26.Board of Police Proceedings. 1780. Jul 18, 4L, CO5/519, National Archives, Kew; Alexander Innes to [John André], Camp at Manigault[']s House, May 21, 1780, Henry Clinton Papers, 1730–1795, William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor; Eliza Pinckney to [?], Charleston, Sept. 25, 1780, Charles Cotesworth Pinckney Family Papers, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., 1st ser., box 5; Josiah Smith to George Appleby, St. Augustine, Dec. 2, 1780, “Josiah Smith Letter Book, 1771–1784,” Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 405–406; Josiah Smith to George Smith, St. Augustine, Dec. 5, 1780, “Josiah Smith Letter Book, 1771–1784,” Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 412; Boston King, “Memoirs of the Life of Boston King, a Black Preacher,” The Methodist Magazine 21 (Mar.–June 1798): 107; David Ramsay, The History of the Revolution of South Carolina 2 vols. (Trenton, 1785), 67; H. H. Ravenel, Eliza Pinckney (New York, 1925), 272; Letters of Eliza Pinckney,” SCHM 76 (1975), 165–66.

- 27.William Burrows to ? 1781. Feb 27, PRO 30/11/105/4–5.

- 28.Simpson to Clinton. 1780. Jul 16, Carleton Papers, PRO 30/55/24. According to Robert Bass, an unusually rainy summer had produced a larger than usual crop of malarial mosquitoes. Robert D. Bass, Swamp Fox: The Life and Campaigns of General Francis Marion (New York: Henry Holt and Co., 1959), 61–62.

- 29.Davies K. G, editor. James Simpson to William Knox. Documents of the American Revolution, 1770–1783 Colonial Office Series. 1780 Dec 31;18:268. Transcripts, 1780. Among those who would die of fever in Charleston that year was the British commissary of barracks, whose wife, Mary O'Callaghan Baddeley, became Clinton's mistress. William H. Hallahan, The Day the Revolution Ended: 19 October 1781 (New York: Wiley, 2004), 89. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walter Edgar. Partisans and Redcoats: the Southern Conflict that Turned the Tide of the American Revolution. New York: Perennial; 2001. On the atrocity issue in South Carolina. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Charles Stedman. The History of the Origin, Progress, and Termination of the American War. 2 vols. London: 1794. 2: 193n, 217n; H. H. Ravenel, Eliza Pinckney (New York, 1925), 290. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Uhlendorf Bernhard A., translator and editor. Cornwallis to Clinton. 1780. Jul 16, PRO 30/55/24; Cornwallis to Clinton, July 16, 1780, PRO 30/72/34–35; Revolution in America: Confidential Letters and Journals 1776–1784 of Adjutant General Major Baurmeister of the Hessian Forces, (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1957), 369.

- 33.Balfour to Rawdon. 1780. Oct 29, PRO 30/11/3/359–60; Balfour to Rawdon, Nov. 1, 1780, PRO 30/11/4/9–10; Balfour to Cornwallis, Nov. 17, 1780, PRO 30/11/4/152.

- 34.Robert Jackson. A Treatise on the Fevers of Jamaica with Some Observations on the Intermitting Fever of America. Vol. 301. London: 1791. p. 303. [Google Scholar]

- 35.John McNamara Hayes to Cornwallis. 1780. Nov 15, PRO, 30/11/4/134; Alured Clarke to Cornwallis, Nov. 29, 1780, PRO 30/11/4/236; Franklin and Mary Wickwire, Cornwallis: the American Adventure (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1970), 245–46.

- 36.Alured Clarke to Cornwallis. 1780. Jul 10, PRO 30/11/2/258–61, Clarke to Cornwallis, Aug. 30, 1780, PRO 30/11/63/83–84; Clarke to Cornwallis, Oct. 5, 1780, PRO 30/11/3/86–87.

- 37.Cornwallis to Balfour. 1780. Sep 27, PRO 30/11/80/48–49.

- 38.Cornwallis to Clinton. 1780. Aug 20, PRO 30/11/76/3–4.

- 39.Wemyss to Cornwallis. 1780. Jul 29, PRO 30/11/2/389–90; Wemyss to Cornwallis, Aug. 4, 1780, PRO 30/11/63/17–18; Franklin and Mary Wickwire, Cornwallis: the American Adventure (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1970), 245.

- 40.Cornwallis to Wemyss. 1780. Jul 30, PRO 30/11/78/61–63.

- 41.Balfour to Cornwallis. 1780. Jul 17, PRO 30/11/2/317–318.

- 42.Rawdon to Cornwallis. 1780. Jul 17, PRO 30/11/2/329–30; Rawdon to Cornwallis, August 1, 1780, PRO 30/11/63/3–4.

- 43.Memorial from Officers of the Provincial Regiments. 1780. Aug 25, PRO 30/11/2/362.

- 44.Cornwallis to Clinton. 1780. Aug 20, PRO 30/11/76; Cornwallis to Clinton, Aug. 10, 1780, Carleton Papers, PRO 30/55/25; Rawdon to Cornwallis, Aug. 1, 1780, PRO 30/11]63/3–4.

- 45.Robert Jackson. A Treatise on the Fevers of Jamaica, With Some Observations on the Intermitting Fever of America. London: 1791. pp. 83–84. McArthur to Cornwallis, July 29, 1780, PRO 30/11/2/383–84. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cornwallis to Wemyss. 1780. Jul 30, PRO 30/11/78/61; Cornwallis to Rawdon, Aug. 1, 1780, PRO 30/11/79/2.

- 47.Banastre Tarleton. A History of the Campaigns of 1780 and 1781 in the Southern Provinces of North America. London: 1787. p. 152. I owe this reference to Elizabeth Fenn. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cornwallis to Clinton. 1780. Aug 6, Carleton Papers, PRO 30/55/25, Cornwallis to Clinton, Aug. 20, 1780, PRO 30/11/76; Cornwallis to Wemyss, July 30, 1780, PRO 30/11/78/61–64; Cornwallis to Rawdon, Aug. 1, 1780, PRO 30/11/79/2–3; Rawdon to Cornwallis, Aug. 1, 1780, PRO 30/11/63/3–4. In November, Banastre Tarleton wrote from Singleton's Mills that all the people in the area were up in arms “except such as have the smallpox.” Tarleton to Turnbull, Nov. 5, 1780, PRO 30/11/4/63.

- 49.Return of the Army in Camden. 1780. Aug 13, PRO 30/11/103/3; Cornwallis to Lord George Germain, Aug. 20, 1780, Aug. 21, 1780, PRO 30/11/76; James Martin to Lord George Germain, Aug. 18, 1780, CO5/176, America and West Indies, National Archives, Kew; Charles Stedman, The History of the Origin, Progress, and Termination of the American War 2 vols. (London, 1794) 2: 205; George Hanger, An Address to the Army; in Reply to Strictures, By Roderick Mackenzie on Tarleton's History of the Campaigns of 1780 and 1781 (London, 1789), 9n; Banastre Tarleton, A History of the Campaigns of 1780 and 1781, in the Southern Provinces of North America (Dublin, 1787), 137–38, 191; John Buchanan, The Road to Guilford Courthouse: The American Revolution in the Carolinas (New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1997), 157. Many of Gates' men were also ill—mainly with diarrhea—from the effects of marches, fatigue, and poor food. See Christopher Ward, The War of the Revolution 2 vols. (New York: The Macmillan Co., 1952), 724.

- 50.Cornwallis to Clinton. 1780. Aug 23, Carleton Papers, PRO 30/55/25.

- 51.Cornwallis to Balfour. Sept. 12, 13, 18, 1780, PRO 30/11/80/16, 17, 20–21, 25–26; Cornwallis to Turnbull, Sept. 11, 1780, PRO 30/11/80/16; Cornwallis to Lt. Col. Cruger, Sept. 12, 1780, PRO 30/11/80/19; Wemyss to Cornwallis, Aug. 28, 1780, PRO 30/11/63/79–80; Wemys to Cornwallis, Sept. 3, 1780, The Cornwallis Papers: Abstracts of Americana comp. George Reese (Charlottesville: The University Press of Virginia, 1970), 103; Franklin and Mary Wickwire, Cornwallis: the American Adventure (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1970), 245. Oddly, Cornwallis wrote that he had “great hopes of the 63d recovering [in Camden] for the troops never suffered much at that place.”.

- 52.Cornwallis to Lord George Germain. 1780. Sep 19, PRO 30/11/76/17.

- 53.SCHM. “Letters of Eliza Pinckney,”. 1975;76:163. see also, Thomas Pinckney to Maj. J. Money, Sept. 22, 1780, PRO 30/11/3/84–85. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Charles Ross., editor. The Correspondence of Charles, First Marquis Cornwallis. 3 vols. London: 1780. Aug 29, Cornwallis to Clinton; p. 1. 1859. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maj. England to Cornwallis. 1780. Oct 1, PRO 30/11/3/162–63; Lt. Col. George Turnbull to Cornwallis, Oct. 2, 1780, PRO 30/11/3/172–73.

- 56.Cornwallis to Balfour. 1780. Sep 15, PRO 30/11/80/23.

- 57.Cornwallis to Maj. Patrick Ferguson. 1780. Sep 20, p. 196. PRO 30/11/80/33; Banastre Tarleton, A History of the Campaigns of 1780 and 1781, in the Southern Provinces of North America (Dublin, 1787)

- 58.Cornwallis to Clinton. 1780. Sep 22, PRO 30/11/72/5.

- 59.Cornwallis to Wemyss. 1780. Oct 7, PRO 30/11/81/26A–27; Cornwallis to Lt. Col. Turnbull, Oct. 7, 1780, PRO 30/11/81/30.

- 60.Cornwallis to Maj. England. 1780. Sep 20, PRO 30/11/80/31; Maj. Archibald McArthur to Cornwallis, Oct. 7, 1780, PRO 30/11/3/199–200.

- 61.Cornwallis to Clinton. 1780. Sep 22, PRO 30/11/72/54; Cornwallis to Maj. England, Sept. 20, 1780, PRO 30/11/80/31; Cornwallis to Lt. Archibald Campbell, Sept. 20, 1780, PRO/30/11/80/29; Cornwallis to Maj. Patrick Ferguson, Sept. 20, 1780, PRO 30/11/80/33; Robert Bass, The Green Dragoon: The Life of Banastre Tarleton and Mary Robinson (London: Alan Redman, 1957), 106; Robert D. Bass Swamp Fox: The Life and Campaigns of General Francis Marion (New York: Henry Holt and Co., 1959, 72–73.

- 62.Cornwallis to Balfour. 1780. Sep 21, PRO 30/11/80/35; Cornwallis to Clinton, Sept. 22, 1780, PRO 30/11/72/54–55; Robert Bass, The Green Dragoon: The Life of Banastre Tarleton and Mary Robinson (London: Alan Redman, 1957), 106; Robert Bass, The Gamecock: The Life and Campaigns of General Thomas Sumter (New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1961), 86.

- 63.Cornwallis to Clinton. 1780. Sep 22, PRO 30/11/72/56; George Hanger, The Life, Adventures, and Opinions of George Hanger (London, 1801), 172 (quotation), 179–181; George Hanger, An Address to the Army; in Reply to Strictures, By Roderick Mackenzie on Tarleton's History of the Campaigns of 1780 and 1781 (London, 1789), 68–70; Charles Stedman, The History of the Origin, Progress, and Termination of the American War 2 vols. (London, 1794) 2: 216; John Buchanan, The Road to Guilford Courthouse: The American Revolution in the Carolinas (New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1997), 186–90.

- 64.Cornwallis to Balfour. 1780. Oct 1, PRO 30/11/81/2; Cornwallis to Ferguson, Oct. 6, 1780, PRO 30/11/81/23; Cornwallis to Balfour, Oct. 7, 1780, PRO30/11/81/25; Cornwallis to Ferguson, Oct. 8, 1780, PRO 30/11/81/31; Robert Bass, The Green Dragoon: The Life of Banastre Tarleton and Mary Robinson (London: Alan Redman, 1957), 107–08; Franklin and Mary Wickwire, Cornwallis: the American Adventure (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1970), 195; W. J. Wood, Battles of the Revolutionary War, 1775–1781 (Chapel Hill: Algonquin Books, 1990), 197.

- 65.Charles Ross. The Correspondence of Charles, First Marquis Cornwallis. 1. 3 vols. London: 1859. p. 59. footnote. [Google Scholar]

- 66.J. Money to Balfour. 1780. Oct 10, PRO 30/11/81/34.

- 67.Balfour to Cornwallis. 1780. Aug 31, PRO 30/11/63/87–88.

- 68.Balfour to Cornwallis. 1780. Oct 10, PRO 30/11/3/205–06.

- 69.Rawdon to Turnbull. Oct. 19, 20, 21, 22, 1780, PRO 30/11/3/241–242, 245–46, 251–252, 257–58; Rawdon to Balfour, Oct. 21, 1780, PRO 30/11/3/253–54; Rawdon to Gen. Alexander Leslie, Oct. 24, 1780, PRO 30/11/3/267–70; Rawdon to Col. Cruger, Oct. 26, 1780, PRO 30/11/3/285–86; Balfour to Rawdon, Oct. 26, 1780, PRO 30/11/3/289–90; Rawdon to Clinton, Oct. 28, 1780, PRO 30/11/3/297–98; Lt. Col. Alexander Innes to Cornwallis, Oct. 31, 1780, PRO 30/11/3/344–45.

- 70.Balfour to Cornwallis. 1780. Nov 5, PRO 30/11/4/27–34.

- 71.Charles Stedman. The History of the Origin, Progress, and Termination of the American War. 2 vols. London: 1794. pp. 224–25. 2. 225n, quotation on 225; Rawdon to Clinton, Oct. 28, 1780, Documents of the American Revolution, 1770–1783 Colonial Office Series, edited by. K. G. Davies, 18: Transcripts, 1780, 215. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Turnbull to Cornwallis. Nov. 3, 4, 1780, PRO 30/11/4/14–15, 25–26.

- 73.Rawdon to Balfour. 1780. Oct 21, PRO 30/11/3/253–54.

- 74.Turnbull to Cornwallis. 1780. Nov 10, PRO 30/11/4/93–94.

- 75.Rawdon to Cornwallis. 1780. Nov 15, PRO 30/11/4/132–33; John Buchanan, The Road to Guilford Courthouse: The American Revolution in the Carolinas (New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1997), 242.

- 76.John McNamara Hayes to Cornwallis. 1780. Nov 15, PRO 30/11/4/134.

- 77.Cruger to Cornwallis. Nov. ? 1780, PRO/30/11/4/225–26.

- 78.Rawdon to Cornwallis. 1780. Dec 17, PRO 30/11/4/343–44.

- 79.Davies K. G, editor. Documents of the American Revolution, 1770–1783: Colonial Office Series. Vol. 18. Dublin: Irish University Press; 1780. Dec 9, Tonyn to Germain; p. 253. 1978) Transcripts, 1780. About the same time, Carolinian Josiah Smith wrote a friend that “Since the capitulation of Charles Town…a scene of devastation & distress has marked the route of both armies & their various detachments that I may in truth say, the sword, the pestilence and fire hath ravaged our Land” Josiah Smith to James Poyas St. Augustine, Dec. 5, 1780, “Josiah Smith Letter Book, 1771–1784,” Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, p. 411. (Thanks to Elizabeth Fenn for giving me this excerpt) [Google Scholar]

- 80.Willcox William B., editor. The American Rebellion. New Haven: Yale University Press; 1781. Jan 8, Leslie to Cornwalis; p. 231. Carleton Papers, PRO 30/55/27 Henry Clinton. 1954) [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cornwallis to Clinton. 1781. Apr 10, PRO 30/11/5/207–08. This letter is also in Henry Clinton, The American Rebellion, ed. by William B. Willcox (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1954), 508–10, and The Clinton-Cornwallis Controversy ed. by Benjamin Franklin Stevens, 2 vols. (London, 1888), 1: 395–99; Cornwallis to Maj. Gen. Phillips, April 10, 1781, in Charles Ross, ed., The Correspondence of Charles, First Marquis Cornwallis 3 vols. (London, 1859), 1: 87–88; Themistocles, A Reply to Sir Henry Clinton's Narrative (London, 1783), 14n; Charles Stedman, The History of the Origin, Progress, and Termination of the American War 2 vols. (London, 1794) 2: 353–55; 247.

- 82.Balfour to Cornwallis. 1780. Nov 7, PRO 30/11/4/57–58.

- 83.Edgar South Carolina: A History. :236–37. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Papers of Nathanael Greene. 12. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press; 1783. Mar 28, Maj. Joseph Eggleston to Greene; p. 545. 1976– ) Greene to Benjamin Guerard, March 31, 1783, Papers of Nathanael Greene (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1976– ), 12: 553. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Colonial Office Series. Clinton to Germain. In: Davies K. G, editor. Documents of the American Revolution. Dublin: Irish University Press; 1781. Dec 26, pp. 1770–1783. 1978), Calendar, 1781–1783, 19: 234. [Google Scholar]