Abstract

Transcription is thought to be regulated by recruitment of transcription factors, adaptors, and certain enzymes to cis-acting elements through protein–DNA interactions and protein–protein interactions. To better understand transcription, a method with the capability to detect in vivo recruitment of these individual proteins will be essential. Toward this end, we use a previously undescribed in vivo method that we term protein position identification with nuclease tail (PIN*POINT). In this method, a fusion protein composed of a chosen protein linked to a nonsequence-specific nuclease is expressed in vivo, and the binding of the protein to DNA is made detectable by the nuclease-induced cleavage near the binding site. In this article, we used the technique protein position identification with nuclease tail to study the effect of the β-globin locus control region (LCR) and promoter elements on the recruitment of transcription factor Sp1 to the β-globin promoter. We present evidence that the hypersensitive sites of the LCR synergistically enhance the recruitment of a multimeric Sp1 complex to the β-globin promoter and that this may be accomplished by protein–protein interactions with proteins bound to the LCR, the upstream activator region, and, possibly, general transcription factors bound near the “TATA” box.

Protein–DNA and protein–protein interactions are central to nuclear processes such as transcription and DNA replication. In vitro techniques developed to visualize the protein complex formed on a particular DNA sequence such as electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) and in vitro footprinting have been valuable tools in the understanding of such processes (1). These techniques, however, have serious limitations. Because transcription occurs in an environment far more complex than can be duplicated in vitro, results derived from these techniques may not be applicable in the cellular context (2). In vivo footprinting, on the other hand, reflects protein–DNA interaction in a living cell but does not identify the complex creating the footprint. Another strategy commonly used to determine transcription factor–DNA interaction in vivo is to inactivate or overexpress the transcription factor and assess its effects on the transcription of a gene containing the putative binding site for the transcription factor. Experiments using this type of strategy are difficult to interpret, however. If there is an observed transcriptional effect, one cannot determine whether it is a direct or an indirect effect. Conversely, if inactivating the transcription factor has no effect on the transcription of the gene with the putative binding site, it cannot be concluded that the transcription factor does not play a role in the transcription of that gene because other transcription factors might be taking the place of the inactivated transcription factor. Therefore, to understand transcription regulation at the cellular level, an in vivo method capable of detecting recruitment of individual proteins to cis-acting elements will be valuable. With this in mind, we devised PIN*POINT (protein position identification with nuclease tail; Fig. 1) and used it to study the role of the β-globin locus control region (LCR) in the recruitment of transcription factor Sp1 to the human β-globin promoter.

Figure 1.

PIN*POINT strategy. (a) A diagram of the structure of FokI endonuclease showing the DNA sequence-specific and nuclease domains. (b) The expression vector for Sp1 pointer is cotransfected with a target plasmid that contains the Sp1 binding site into MEL cells. The crescent portion of Sp1 (middle of the diagram) represents the DNA binding domain of Sp1. The flexible linker region and the nuclease domain are represented as a string and an arrowhead, respectively. Low molecular weight DNA is recovered and cleavage in the promoter of the target plasmid is detected by primer extension with a radioactively labeled internal primer (∗). For increased sensitivity, ligation-mediated PCR (LM-PCR) may also be used.

The β-globin LCR is the master regulatory element of the β-globin gene cluster (ɛ-Gγ-Aγ-δ-β) (3). Its functional elements reside in five DNase I-hypersensitive sites (5′HS1–5) that synergistically activate (4–9) the transcription of the β-globin gene cluster in a development-specific order (3). Among the hypersensitive sites, 5′HS2–4 are most important for transcription activation (7). Although each of them contain binding sites for transcriptional activators important for globin gene expression including CACCC and E box factors, GATA-1, and NF-E2 (3), they appear to have different properties. For example, only 5′ HS2 functions as an enhancer in transient transfection assays (10) and 5′HS3 possesses the unique capability to open chromatin (4). However, some redundancy among the hypersensitive sites must exist because deletions of single hypersensitive sites either have no effect on expression or mildly reduce (0–30%) expression of the linked β-globin genes (11, 12).

Exactly how the hypersensitive sites activate the expression of the β-globin gene cluster in a development-specific fashion is not clear, but a widely accepted view proposes a direct LCR–promoter interaction that activates transcription (3). However, if the LCR does interact with the promoter directly, its primary role is probably not in determining developmental switching of the β-like genes (13). A transgenic study of multigene constructs without the LCR has demonstrated that correct developmental expression of the γ- and β-globin genes occur in the absence of the LCR (14), albeit at a much lower level. A study of β-globin transcription at the level of individual cells suggests that the LCR increases the probability of expression by establishing and maintaining transcription rather than increasing the transcription rate (13). In heterochromatic regions, the expression of a reporter gene linked to an incomplete LCR was intermittent or was continuous but occurred only in a subpopulation of cells and thus lowered the total level of expression. In those expressing cells, however, the transcription level of the reporter gene linked to the incomplete LCR was similar to that of the reporter gene linked to a complete LCR (5).

How does the LCR increase the probability of transcription? One possible mechanism is by increasing the recruitment of transcriptional activators and the stability of the transcriptional activator–promoter interaction. Among the cis-actin elements in the β-globin promoter, the CACCC boxes (Fig. 2a) appear to be critical for LCR activation (20, 21). In murine erythroleukemia (MEL) cells, a deletion of the CACCC boxes in the β-globin promoter strongly decreases its LCR-induced activity. Moreover, promoter mutations in β-thalassemia patients that decrease β-globin gene expression cluster in the CACCC and TATA boxes.

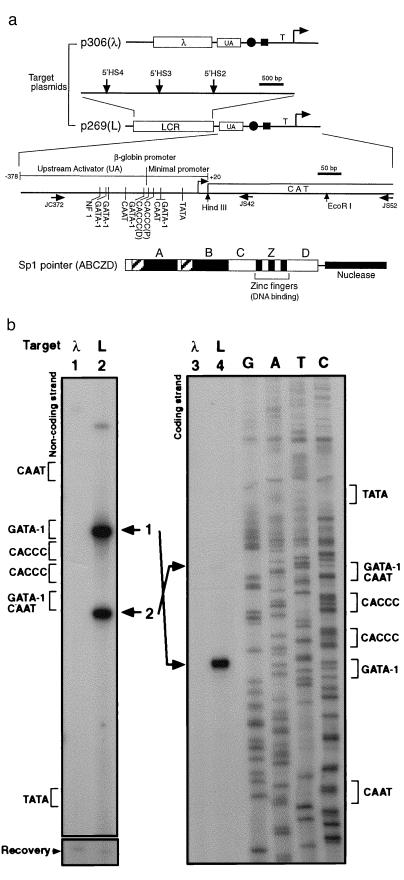

Figure 2.

β-globin LCR recruits Sp1 pointer. (a) Diagram of target plasmids p306 (λ) and p269 (L) is shown at the top. The positions of the hypersensitive sites (β-globin LCR) are indicated with vertical arrows. Also shown are the relative positions of the UA region, the tandem CACCC boxes (solid circle), the overlapping GATA-1/CAAT box (solid rectangle), and the TATA box (T) in the β-globin promoter. The transcription initiation site is indicated by a bent arrow.Transcription factor binding sites in the β-globin upstream activator region and the minimal promoter region (15), the positions of the primers (horizontal arrows) used in this article, and the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase reporter gene (CAT) are shown in the enlarged diagram. The distal and proximal CACCC boxes are indicated as CACCC (D) and CACCC (P), respectively. The structure of the Sp1 pointer ABCZD (16) is shown at the bottom. Domains A and B contain serine/threonine- and glutamine-rich regions, interact with TATA binding protein-associated factors, and are required for transcriptional activation and Sp1 tetramer formation. The zinc fingers (Z) bind DNA in a sequence-specific manner, and domain D is thought to mediate Sp1 tetramer-tetramer interaction (16–18). (b) Recruitment Sp1 pointer ABCZD to target plasmid p306 (λ) (lanes 1 and 3) or p269 (L) (lanes 2 and 4) was detected with PIN*POINT. Primer extensions with radioactively labeled noncoding-strand primer JS42 (Left) and coding-strand primer JC372 (Right) were performed on the recovered DNA. The positions of the promoter elements near the CACCC boxes are indicated for each strand. Bands 1 and 2 (lanes 2 and 4) correspond to the cleavages 5′ and 3′ of the CACCC boxes, respectively. As shown at the bottom (Recovery), the amount of target plasmid in each sample is similar (19).

In the present work, we test whether Sp1 (17), one of the transcriptional activators known to bind to the CACCC boxes, is more efficiently recruited to and stabilized in its interaction with the β-globin promoter in the presence of the LCR. We find that the β-globin LCR strongly promotes the recruitment of a multimeric Sp1 complex to the β-globin promoter in MEL cells. As in transcriptional activation, the individual hypersensitive sites of the β-globin LCR act synergistically in this recruitment. Surprisingly, the TATA box is essential for the recruitment of the Sp1 complex, suggesting that Sp1 and the general transcription factors, which are recruited by transcriptional activators such as Sp1, stabilize or recruit each other.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of Plasmids.

The expression vector for Sp1 pointer ABC (p326) was constructed by linking Sp1 cDNA (containing domains A, B, and C) from pPacSp1 (18) to the nuclease domain of FokI from pCB FOK IR (22) through a linker fragment (encoding amino acids AGGGGGGGGGARL) and inserting it downstream of a fragment containing the cytomegalovirus promoter and an intron from pCIS-2 (obtained from Genentech) (23). Translation initiation site and the nuclear localization signal of simian virus 40 large tumor antigen (24) was inserted at the N terminus of Sp1 cDNA to ensure optimal translation and nuclear localization. The expression vectors for Sp1 pointers ABCZD and ABCD were constructed by adding the missing Sp1 domains to p326. More details on these constructs may be obtained upon request from the authors. Target plasmid p269 was constructed by replacing 5′HS2 of pPN86 (25) [which contains 5′HS2-β-globin promoter (positions −374 to +21) linked to the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase reporter gene] with a fragment containing 5′HS2–4 (mini-LAR) from pHS1234 (26). Target plasmid p306 was constructed by replacing the 5′HS2 of pPN86 with the 2.0-kb HindIII–HindIII fragment of λ phage DNA. The other LCR combination target plasmids were also derived from pPN86 by replacing its 5′HS2 with the indicated hypersensitive site(s) and the flanking regions from pHS1234. Promoter-deletion target plasmids were constructed as follows: The promoter region was first divided into four sections: upstream activator region (UA) (positions −378 to −114), CACCC binding site (positions −113 to −79), CAAT box (positions −78 to −32), and TATA box (positions −31 to +20). Fragments containing the indicated sections flanked by restriction sites NotI (5′) and EcoRI (3′) were amplified by PCR using the following primers: for p405, JS33P (5′-AAGGAAAAAAGCGGCCGCTTAGACCTCACCCTGTGGAGCC-3′) and JS52 (5′-CGTGGTATTCACTCCAGAGCGATGAAAAC-3′); for p407, JS31P (5′-AAGGAAAAAAGCGGCCGCGGCCAATCTACTCCCAGGAGCAG-3′) and JS52; for p403, JS32P (5′-AAGGAAAAAAGCGGCCGCATAAAAGTCAGGGCAGAGCCATCTAT-3′) and JS52; for p404, JS35P (5′-AAGGAAAAAAGCGGCCGCAGCTCTTCCACTTTTAGTGCAT-3′) and JS34P (5′-CCGGAATTCGCCCAGCCCTGGC-3′); for p406, JS33P (5′-AAGGAAAAAAGCGGCCGCTTAGACCTCACCCTGTGGAGCC-3′) and JS34P. After cleaving these fragments with NotI and EcoRI, they were inserted into the NotI–EcoRI sites of p269. The modifications were verified by sequencing.

Transfection and Tissue Culture.

Transient cotransfection of MEL cells was performed with 5–10 μg of the expression vector and 3–5 μg of the target plasmid by electroporating 107 MEL cells at the following settings: 975 μF, 250 V, and resistance level 5 (BTX Electro Manipulator 600) in 0.7 ml of DMEM without serum. After electroporation, the cells were immediately resuspended in 20 ml of DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum and grown in a 5% CO2/95%air incubator at 37°C. Transfected cells were harvested 24–36 hr after transfection and low molecular weight DNA was isolated by a modified Hirt extraction technique (27). Briefly, the harvested cells were washed with PBS (pH 7.4) twice and resuspended in 500 μl of 10 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.8/10 mM EDTA. To this resuspension, 50 μl of 10% SDS was added and the mixture was gently mixed. After 10 min in room temperature, 140 μl of 5 M NaCl was added and the mixture was gently mixed. The resulting mixture was then kept at 4°C overnight. After centrifugation at 15,000 × g at 4°C for 30 min, the supernatant was collected and 20 μg of yeast tRNA and 40 μg of proteinase K were added. After incubation at 50°C for 1–2 hr, the sample was extracted with phenol/chloroform and then with chloroform. After ethanol precipitation, DNA was resuspended in 30 μl of 10 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 8.0).

Primer Extension.

DNA (5 μl) isolated as described above was denatured with 10% dimethyl sulfoxide by heating to 94°C for 2–3 min and quickly cooling on dry ice. To the denatured DNA, 1 μl of 10× Thermo Pol reaction buffer, 2 μl of labeled primer (0.5–1.0 pmol), 1 μl of all four dNTPs (each at 2.5 mM), 0.4 μl of Vent exonuclease-negative polymerase (New England Biolabs), 0.2 μl of distilled H2O, and 0.4 μl of 100 mM MgSO4 were added. This mixture was heated to 94°C for 5 min, annealed at 70°C for 5 min, and primer-extended at 72°C for 5 min. The extended products were electrophoresed on a 6% polyacrylamide gel (National Diagnostics) containing urea in TBE. For the analysis of DNA recovery, 5–10% of the recovered DNA was cleaved with HindIII or EcoRI before primer extension. For the noncoding-strand primer extension, 32P-end-labeled primer JS42 (5′-TACGATGCCATTGGGATATATCAACGGTGG-3′) from the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase gene was used; for the coding-strand primer extension, JC372 (5′-CGATCTTCAATATGCTTACCAAGCTGTG-3′) was used. For p404 and p406 promoter-deletion target plasmids, primer JS52 (5′-CGTGGTATTCACTCCAGAGCGATGAAAAC-3′) was used for primer extension in Fig. 3. The primers JS52 and JS42 were equally effective for primer extension. The analysis of DNA recovery for all samples in this article was performed with JS52.

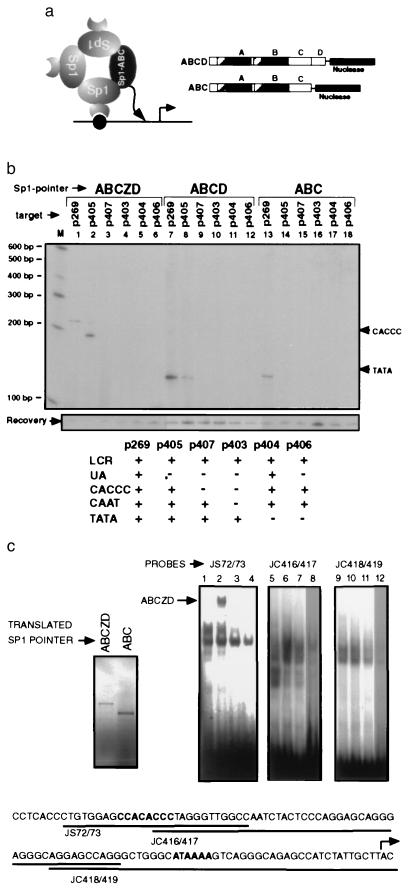

Figure 3.

Promoter elements participate in the formation of a multimeric Sp1 complex. (a) A diagram of hypothetical Sp1–Sp1 interactions that may recruit the Sp1 pointer (solid oval) lacking the DNA binding domain (ABC) is shown on the left and the structure of the Sp1 pointers ABCD and ABC is shown on the right. (b) Recruitment of Sp1 pointers ABCZD (lanes 1–6), ABCD (lanes 7–12), and ABC (lanes 13–18) to target plasmids containing deletions of different promoter elements was analyzed with PIN*POINT. Primer extension on the noncoding strand is shown. The promoter elements that are present (+) and lacking (−) in each of the target plasmids are summarized in the table below. Positions of the distal CACCC box and TATA box are shown on the right. (c) EMSA analysis was performed with in vitro-translated Sp1 pointers ABCZD and ABC (translated product shown in upper left corner) and oligonucleotide probes (JS72/73, JC416/417, and JC418/419) shown below. The proximal CACCC box and TATA box are in boldface type and the transcription initiation site is marked with a bent arrow. EMSA analysis was done with the probes indicated above and rabbit reticulocyte lysate alone (lanes 1, 5, and 9), in vitro-translated Sp1 pointer ABCZD without (lanes 2, 6, and 10) or with competing Sp1 binding oligonucleotide (lanes 3, 7, and 11), and in vitro-translated Sp1 pointer ABC (lanes 4, 8, and 12). The DNA bound ABCZD complex is indicated with an arrow. Competition with a non-Sp1-binding oligonucleotide did not affect this complex, suggesting that it is a sequence specific complex (data not shown).

In Vitro Translation of Sp1–FokI Proteins.

T7 promoter sequence was inserted into the ClaI site of p401 (for p677) and p326 (for p402). In vitro transcription and translation was performed by using the Amersham linked T7 transcription–translation system (rabbit reticulocyte lysate). The [35S]methionine-labeled proteins were electrophoresed in a 4–12% denaturing Tris glycine/acrylamide gel to check for synthesis. Sp1 pointer proteins for EMSA were translated with nonradioactive methionine.

EMSA Analysis.

DNA binding assays were performed in 10 μl containing 5 μl of in vitro-translated Sp1 pointers ABCZD or ABC Sp1–FokI, 0.1 pmol of 32P-labeled oligonucleotides from the β-globin promoter, 4% glycerol, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM DTT, 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.5), and 0.025 unit of poly(dA-dT) (Pharmacia Biotech) at room temperature for 20 min. The samples were resolved on 4% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gels in 0.5× TBE, dried, and subjected to autoradiography. The sequences of the double-stranded oligonucleotide probes are as follows: JS72/73, 5′-CTGTGGAGCCACACCCTAGGGTTGGCCA-3′; JC416/417, 5′-CCCTAGGGTTGGCCAATCTACTCCCAGGAGCAGGGAGGGCAGGAGCCAGG-3′; JC418/419, 5′-AGGAGCCAGGGCTGGGCATAAAAGTCAGGGCAGAGCCATCTATTGCTTAC-3′. For the Sp1 competitor oligonucleotide, 1.75 pmol of Sp1 consensus binding site (Promega; 5′-ATTCGATCGGGGCGGGGCGAGC-3′) was used.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

In PIN*POINT, an expression vector for a fusion protein composed of Sp1, a flexible linker, and the nuclease domain of type IIS endonuclease FokI (22) is transiently transfected with a target plasmid containing the β-globin promoter into MEL cells. The Sp1–nuclease fusion protein (referred to hence forward as the “Sp1 pointer”) then competes with the endogenous pool of Sp1 and other factors in binding to the CACCC boxes in the β-globin promoter of the target plasmid. FokI endonuclease has a sequence-specific DNA binding domain and a separable nuclease domain (Fig. 1a) that cleaves at a defined distance on one side of the recognition sequence, 9 bp for one strand and 13 bp for the other. Because the nuclease domain of FokI lacks sequence specificity, the position and the probability of cleavage by the Sp1 pointer is determined by Sp1 (22, 28, 29). The cleavage site is then detected by primer extension or ligation-mediated PCR.

The PIN*POINT strategy was derived in part from previous in vitro experiments that studied protein–DNA interaction by incorporating cleavage moieties into the protein and more specifically from the work by Kim and Chandrasegaran (22) that showed that chimeric endonucleases can be created by swapping the DNA binding domain of the restriction endonuclease FokI with the DNA binding domain of another protein. However, the present work describes a general approach using protein-directed DNA cleavage to study a complex biological process such as transcription at the level of individual proteins in vivo.

To determine whether the β-globin LCR affects the recruitment of Sp1 to the β-globin promoter, the Sp1 pointer expression vector was cotransfected into uninduced MEL cells with one of two target plasmids: p269 (L), which contains the human β-globin promoter linked to 5′HS2–4 of the human β-globin LCR (mini-LAR) (26), and p306 (λ), which contains the β-globin promoter linked to a fragment of λ phage DNA as a control (Fig. 2a). After the target plasmid was recovered, the cleavage pattern was determined by primer extension (Fig. 2b). We found that the Sp1 pointer cleaved within the β-globin promoter when the promoter was linked to the LCR but not when linked to the λ phage DNA (Fig. 2b, compare lanes 1 and 2 for the noncoding strand and lanes 3 and 4 for the coding strand). The predominant cleavage sites were located approximately 10 bp upstream of the distal CACCC box and 8 bp downstream of the proximal CACCC box in the β-globin promoter (Fig. 2b, bands 1 and 2 in lanes 2 and 4). The extent of the cleavage downstream of the proximal CACCC box varied from experiment to experiment (Figs. 3b and 4). Minor cleavages both upstream and downstream of the CACCC boxes were occasionally seen (Fig. 2b, lane 2). Discrepancies in the intensities of band 2 in the noncoding strand (strong in Fig. 2b, lane 2) and coding strand (weak in Fig. 2b, lane 4) suggest that the nuclease domain does not cleave both strands of DNA at all sites in vivo. We estimate that as much as 10% of the target plasmid was cleaved by the Sp1 pointer (data not shown). Similar results were obtained when the target plasmids were relaxed with topoisomerase I before transfection, suggesting that the superhelicity of the target plasmids is not important for the detection of Sp1 recruitment with PIN*POINT analysis (data not shown). Sp1 specificity of the cleavage shown in Fig. 2b was verified by demonstrating that other control pointers such as Gal4 pointer, composed of the DNA binding domain of Gal4 protein fused to the nuclease domain of FokI, did not cleave the β-globin promoter (data not shown).

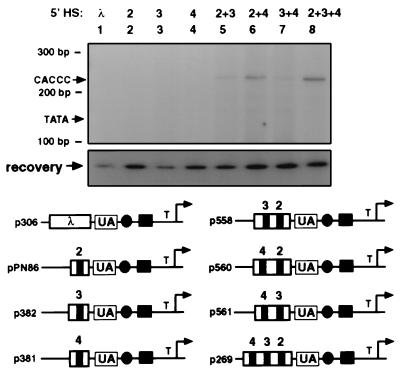

Figure 4.

LCR hypersensitive sites act synergistically in recruiting Sp1 pointer. Recruitment of Sp1 pointer ABCZD to target plasmids containing various combinations of the 5′HSs of the LCR (lanes: 1, p306; 2, pPN86; 3, p382; 4, p381; 5, p558; 6, p560; 7, p561; 8, p269) shown below was analyzed with PIN*POINT. Primer extension on the noncoding strand is shown. Positions of the UA region, the tandem CACCC boxes (solid circle), the overlapping GATA-1/CAAT box (solid rectangle), and the TATA box (T) of the β-globin promoter are also shown. Primer extension was performed as before (Fig. 2b). The site of the cleavage detectable in lanes 5–8 is approximately 10 bp upstream of the distal CACCC box (see Fig. 2b, band 1). The positions of the distal CACCC box and the TATA box are shown with the size markers.

Because Sp1 can exist as homotypic multimers, an Sp1 complex may be composed of two types of Sp1: those that are bound directly to DNA and those that are tethered through protein–protein interactions involving Sp1 domains A, B, and/or D (Fig. 3a) (16). To understand the structure of the Sp1 complex recruited by the LCR, it is important to know whether it contains Sp1 tethered through protein–protein interactions. The cleavage detected in Fig. 2b reflects the recruitment of both Sp1 types because the Sp1 pointer used contained the domains for DNA binding and for Sp1–Sp1 interaction. To determine whether the LCR promotes the recruitment of Sp1 tethered through Sp1–Sp1 interaction, the experiment shown in Fig. 2 was repeated with Sp1 pointers that lacked the Z (DNA binding) domain but contained domains A-C (ABC) or A-D (ABCD) (Fig. 3 a and b). To determine whether other transcription factors binding to the promoter play any role in Sp1 recruitment, target plasmids containing deletions of various promoter elements were tested for each Sp1 pointer. Fig. 3b shows that the Sp1 pointer ABCZD cleaves UA-region-deleted target plasmid p405 albeit with a slightly different cleavage pattern (Fig. 3b, compare lanes 1 and 2). On the other hand, a deletion of the CACCC (Fig. 3b, lane 3) boxes completely abolished detectable cleavage, indicating that the CACCC boxes are essential for Sp1 recruitment. Surprisingly, a deletion of the TATA box also abolished detectable cleavage (Fig. 3b, lane 5). Because the target plasmid p404 also contained a deletion of the transcription initiation site in addition to the TATA box, we repeated the study with a target plasmid containing a site-directed mutation of the TATA box and found that it also did not recruit Sp1 pointer ABCZD (data not shown). Sp1 pointers ABCD and ABC were also recruited to the promoter but unlike the Sp1 pointer ABCZD, the cleavage site was located 4 bp downstream of the TATA box (Fig. 3b, lanes 7 and 13). Cleavage by Sp1 pointer ABCD also required the CACCC (Fig. 3b, lane 9) and TATA (Fig. 3b, lane 11) boxes but not the UA region (Fig. 3b, lane 8). In contrast, the cleavage by the Sp1 pointer ABC was undetectable with the deletion of UA (Fig. 3b, compare lanes 13 and 14), suggesting that additional interactions with factors binding to the UA region may contribute to Sp1 recruitment. The role of this interaction may not have been as prominent for the Sp1 pointers ABCZD and ABCD because of the additional interactions mediated through the zinc finger (30) and D domains (16). It also appears that cleavage by Sp1 pointers ABCD and ABC, when compared with recovered DNA, is slightly weaker than that by ABCZD, indicating that DNA binding is important for recruitment as one would expect. One possible explanation for the difference in the cleavage sites of Sp1 pointers ABCZD and ABC or ABCD is that the zinc finger domain affects the trajectory of the nuclease tail in such a way that the nuclease domain of ABCZD is positioned closer to the CACCC box than the TATA box but that of ABC and ABCD is closer to the TATA box. Without knowing the structure of Sp1 and these Sp1-derived proteins, such issues are difficult to address at this point.

Although the result shown in Fig. 3b is consistent with the notion that Sp1 pointers without the DNA binding domain, ABC and ABCD, are recruited through protein–protein interaction, we had to rule out the possibility that in making these fusion proteins, we created proteins capable of binding to the proximal promoter region. To do this, we performed EMSA analysis with in vitro-translated Sp1 pointers ABCZD and ABC and oligonucleotide fragments spanning the region from the proximal CACCC box to the transcription initiation site of the β-globin promoter (Fig. 3c) as probes. Although the reticulocyte lysate alone contained probe binding complexes (Fig. 3c, lanes 1, 5, and 9), which may partially obscure the complexes formed by the Sp1 pointers, it appears that Sp1 pointer ABCZD bound to the CACCC box-containing probe JS72/73 sequence specifically (Fig. 3c, lanes 2 and 3, and data not shown) but not to the others (Fig. 3c, lanes 6 and 10). On the other hand, Sp1 pointer ABC did not appear to bind any of the probes (Fig. 3c, lanes 4, 8, and 12). Therefore, Sp1 pointer ABC was most likely recruited by protein–protein interaction in vivo.

Because Sp1 pointer is being overexpressed and the target DNA is in a plasmid form in these experiments, it is worth noting that these findings may not mimic Sp1 recruitment to the genomic β-globin locus in all aspects. For example, we cannot rule out the possibility that overexpression of Sp1 pointer might displace other CACCC box binding proteins such as EKLF (31). Whatever CACCC box factor binds to the endogenous β-globin promoter, and there could be more than one, these experiments demonstrate how PIN*POINT can be useful for detecting not only those proteins directly bound to DNA but also those recruited through protein–protein interactions.

Mutations in the proximal CACCC box lead to a much more severe form of β-thalassemia than those in the distal CACCC box, suggesting that the proximal box is more critical to the β-globin promoter activity (20). To study the role of each of the CACCC boxes in Sp1 recruitment, we examined cleavage by ABCZD in target plasmids containing a site-directed mutation of either the proximal or the distal CACCC box. Although the mutation of the distal box did not significantly affect cleavage when compared with the wild-type promoter, the mutation of the proximal box completely abolished cleavage, suggesting that Sp1 is recruited predominantly by the proximal box (data not shown), consistent with the severity of β-thalassemia when it is mutated.

The requirement for the TATA box in Fig. 3b is intriguing in light of the observation that the cleavage sites of the Sp1 pointers ABC and ABCD can be very close to the TATA box. The recruitment of general transcription factors such as TFIID to the TATA box is generally thought to be downstream of the recruitment of transcription activators such as Sp1 (19, 32, 33–35); however, our findings are consistent with the notion that general transcription factors bound to the TATA box (e.g., TFIID) also help recruit transcriptional activators (28). Potential targets of Sp1 interaction might include TATA-binding-protein-associated factors such as hTAFII 55 and dTAFII 110, which have been shown to interact with Sp1 in vitro (19, 33).

The individual hypersensitive sites of the LCR act synergistically to activate transcription. To test whether recruitment of the Sp1 pointer ABCZD to the β-globin promoter was dependent on such synergy, target plasmids containing one or two hypersensitive sites from the LCR in different combinations were tested (Fig. 4). Compared with the target plasmid containing 5′HS2–4 (p269), the cleavage was weaker on the target plasmids containing 5′HS2 and -3 (by 6-fold), 5′HS2 and -4 (by 2-fold), or 5′HS3 and -4 (by 6-fold) but were detectable (Fig. 4, lanes 5–7). There was no detectable cleavage when only one of the hypersensitive sites was present (Fig. 4, lanes 2–4), suggesting that synergy between the hypersensitive sites is important for Sp1 recruitment. Our observation that cleavage by Sp1 pointer is undetectable with 5′HS2 alone was unexpected because it has been shown that it can function as an enhancer (10, 26, 25, 36). One possible explanation is that nuclease cleavage is inefficient in vivo, and as a result, weak Sp1 recruitment and pointer cleavage might be undetectable above the background of endogenous nuclease activity. Therefore, we cannot make any conclusions regarding Sp1 recruitment by 5′HS2 alone other than that it is stronger in combination with other hypersensitive sites.

Understanding transcription in the context of a cell has been hindered by the complexity of the nuclear environment. In addition to transcription factors and cis-acting DNA elements, the chromatin, DNA replication machinery (37), and compartmentalization within the nucleus (38) also affect transcription. Another level of complexity arises from the observation that some transcriptional factors (e.g., TFIID) may be composed of different subunits depending on the gene (39) and the cell type (40). For these reasons, it will be useful to begin defining nuclear complexes in terms of individual proteins bound either directly or indirectly to a specific sequence of DNA. This PIN*POINT study on the role of the β-globin LCR and the promoter elements in the recruitment of transcription factor Sp1 marks a departure point in this direction.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Elliot Epner and Mark Groudine for pHS1234, Dr. Srinivasan Chandrasegaran for pCB FOK IR, Dr. Robert Tjian for Sp1 cDNA, Genentech for pCIS-2, and Dr. Paul Ney for pPN86. We thank Dr. David Levens and the members of the Molecular Hematology Branch (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute) for helpful comments on the manuscript.

ABBREVIATIONS

- LCR

locus control region

- 5′HS

5′ DNase I-hypersensitive site

- EMSA

electrophoretic mobility shift assay

- MEL

murine erythroleukemia

- UA

upstream activator

- PIN*POINT

protein position identification with nuclease tail

References

- 1.Ausubel F M. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. New York: Wiley; 1994. , Chapter 12. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolffe A. In: Chromatin. Wolffe A, editor. London: Academic; 1996. pp. 148–234. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Orkin S H. Eur J Biochem. 1995;231:271–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ellis J, Tan-Un K C, Harper A, Michalovich D, Yannoutsos N, Philipsen S, Grosveld F. EMBO J. 1996;15:562–568. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Milot E, Strouboulis J, Trimborn T, Wijgerde M, de Boer E, Langeveld A, Tan-Un K, Vergeer W, Yannoutsos N, Grosveld F, Fraser P. Cell. 1996;87:105–114. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81327-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bungert J, Dave U, Lim K C, Lieuw K H, Shavit J A, Liu Q, Engel J D. Genes Dev. 1995;9:3083–3096. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.24.3083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fraser P, Pruzina S, Antoniou M, Grosveld F. Genes Dev. 1993;7:106–113. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.1.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collis P, Antoniou M, Grosveld F. EMBO J. 1990;9:233–240. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08100.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fraser P, Hurst J, Collis P, Grosveld F. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:3503–3508. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.12.3503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Talbot D, Grosveld F. EMBO J. 1991;10:1391–1398. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07659.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fiering S, Epner E, Robinson K, Zhuang Y, Telling A, Hu M, Martin D I, Enver T, Ley T J, Groudine M. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2203–2213. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.18.2203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hug B A, Wesselschmidt R L, Fiering S, Bender M A, Epner E, Groudine M, Ley T J. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:2906–2912. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.6.2906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martin D I, Fiering S, Groudine M. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1996;6:488–495. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(96)80072-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Starck J, Sarkar R, Romana M, Bhargava A, Scarpa A L, Tanaka M, Chamberlain J W, Weissman S M, Forget B G. Blood. 1994;84:1656–1665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Antoniou M, deBoer E, Habets G, Grosveld F. EMBO J. 1988;7:377–384. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb02824.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pascal E, Tjian R. Genes Dev. 1991;5:1646–1656. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.9.1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kadonaga J T, Courey A J, Ladika J, Tjian R. Science. 1988;242:1566–1570. doi: 10.1126/science.3059495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Courey A J, Tjian R. Cell. 1988;55:887–898. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90144-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chiang C M, Roeder R G. Science. 1995;267:531–536. doi: 10.1126/science.7824954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weatherall D J, Clegg J B, Wood S G. In: The Metabolic Basis of Inherited Disease. Scriver C R, Beaudet A L, Sly W S, Valle D, editors. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1989. pp. 2281–2339. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Antoniou M, Grosveld F. Genes Dev. 1990;4:1007–1013. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.6.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim Y G, Chandrasegaran S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:883–887. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.3.883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choi T, Huang M, Gorman C, Jaenisch R. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:3070–3074. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.6.3070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rouet P, Smih F, Jasin M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:6064–6068. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.13.6064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ney P A, Sorrentino B P, McDonagh K T, Nienhuis A W. Genes Dev. 1990;4:993–1006. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.6.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Forrester W C, Novak U, Gelinas R, Groudine M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:5439–5443. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.14.5439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anant S, Subramanian K N. Methods Enzymol. 1992;216:20–29. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(92)16005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim Y G, Cha J, Chandrasegaran S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:1156–1160. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.3.1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang B, Schaeffer C J, Li Q, Tsai M D. J Protein Chem. 1996;15:481–489. doi: 10.1007/BF01886856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Merika M, Orkin S H. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:2437–2447. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.5.2437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller I J, Bieker J J. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:2776–2786. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.5.2776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pugh B F, Tjian R. Cell. 1990;61:1187–1197. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90683-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gill G, Pascal E, Tseng Z H, Tjian R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:192–196. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.1.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stargell L A, Struhl K. Trends Genet. 1996;12:311–315. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(96)10028-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Struhl K. Cell. 1996;84:179–182. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80970-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Caterina J J, Ryan T M, Pawlik K M, Palmiter R D, Brinster R L, Behringer R R, Townes T M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:1626–1630. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.5.1626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fox C A, Ehrenhofer-Murray A E, Loo S, Rine J. Science. 1997;276:1547–1551. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5318.1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maillet L, Boscheron C, Gotta M, Marcand S, Gilson E, Gasser S M. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1796–1811. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.14.1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Walker S S, Reese J C, Apone L M, Green M R. Nature (London) 1996;383:185–188. doi: 10.1038/383185a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dikstein R, Zhou S, Tjian R. Cell. 1996;87:137–146. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81330-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]