Abstract

Background:

Asymptomatic deep venous thrombosis (DVT) has been reported in 60% to 100% of persons with spinal cord injury (SCI). Several guidelines have been published detailing recommended venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis after acute SCI. Low-molecular-weight heparin, intermittent pneumatic compression (IPC) devices, and/or graduated compression stockings are recommended. Vena cava filters (VCFs) are recommended for secondary prophylaxis in certain situations.

Objective:

To clarify the use of vena cava filters in patients with SCI.

Methods:

Literature review.

Results:

Prophylactic use of vena cava filters has expanded in trauma patients, including individuals with SCI. Filter placement effectively prevents pulmonary emboli and has a low complication rate. Indications include pulmonary embolus while on anticoagulant therapy, presence of pulmonary embolus and contraindication for anticoagulation, and documented free-floating ileofemoral thrombus. VCFs should be considered in patients with complete motor paralysis caused by lesions in the high cervical cord (C2 and C3), with poor cardiopulmonary reserve, or with thrombus in the inferior vena cava despite anticoagulant prophylaxis. Three optional retrievable filters that are approved for use are discussed.

Conclusion:

Retrievable VCFs are a safe, feasible option for secondary prophylaxis of VTE in patients with SCI. Objective criteria for temporary and permanent placement need to be defined.

Keywords: Spinal cord injuries, Deep vein thrombosis, Venous thromboembolism, Pulmonary embolism, Trauma, Thromboprophylaxis, Vena cava filters, Greenfield filters, Recovery, OptEase, TrapEase

INTRODUCTION

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a well-recognized complication of spinal cord injury (SCI) and one that may lead to significant morbidity and mortality. Although the exact incidence of deep venous thrombosis (DVT) after SCI is unknown, asymptomatic DVT has been reported in 60% to 100% of persons with SCI (1). DVT occurs most frequently during the first 2 weeks after injury; the incidence is low in the first 72 hours (2). Most thromboembolic events occur within 3 months of acute SCI. (3,4). Pulmonary embolism (PE) has been reported to occur in approximately 5% of patients with SCI, and it is the third leading cause of death in all patients in the first year after injury (2). With increasing awareness of and prophylaxis for VTE, more recent Model SCI System data reveal the incidences of DVT and PE during acute rehabilitation are 9.8% and 2.6%, respectively. The incidence falls to 2.1% and 1% at 1- and 2-year follow-ups, respectively (5). Although all persons with SCI are at increased risk of VTE, there is a greater risk of DVT in men, in those with motor complete injuries, and in paraplegia compared with tetraplegia (2).

Nontraumatic SCI comprises a significant proportion of inpatient SCI rehabilitation admissions, ranging from 25% to 35% (6). Nontraumatic SCI includes sources of injury such as neoplasms, spinal stenosis, and myelopathies. Unfortunately, there are few published data on the medical complications of nontraumatic SCI including the incidences of VTE. In the largest series reported to date (6) (117 consecutive SCI rehabilitation inpatient admissions), there was a statistically significant difference between rates of DVT after nontraumatic compared with traumatic SCI (8% and 23%). In the same series, the proportion of complete injury comparing nontraumatic and traumatic SCI was 5.3% and 45.6%, respectively. This implies that, in general, persons with traumatic SCI incur relatively greater neurologic impairment and corresponding venous stasis and possible endothelial injury. Nevertheless, because the risk of VTE in persons with nontraumatic SCI is still high, strategies for prophylaxis and treatment of VTE in traumatic SCI may still be pertinent and applicable to the nontraumatic SCI population.

VENOUS THROMBOEMBOLISM AND TRAUMA

The reported incidence of VTE after trauma in general varies from 7% to 58% depending on the demographics, nature of injuries, method of detection, and type of VTE prophylaxis (if any) used in the study population (7–11). Until the National Trauma Data Bank analysis by Knudson et al (11), the best estimate of the incidence came from the 1994 prospective venographic study of trauma patients by Geerts et al (10). In this study, 201 of 349 (58%) trauma patients who did not receive prophylaxis developed DVT. DVT was diagnosed in 81% of patients with SCI. Only 2% (3 of 201) of the patients with venographic evidence of thrombosis in this series had clinical features suggesting DVT. Pulmonary embolism was suspected clinically in 11% (39 of 349) but was confirmed in only 2%. The rate of fatal PE was less than 1% (3 of 349), and all of these events occurred without warning. More recently, a study by Schultz et al (12) of 90 patients with moderate to severe injuries observed a 24% incidence of asymptomatic PE through the use of helical computed tomography scan screening.

An analysis of the National Trauma Data Bank from 1994 to 2001 (131 participating trauma centers) revealed 1,602 VTE cases from a total of 450,375 trauma admissions (0.36%) (11). There were 998 DVTs, 522 PE (0.12% incidence of PE), and 82 occurrences of DVT with PE. The mortality rate among patients with PE was 18.6%. There were 2,852 cases of SCI with paralysis. Logistic regression analysis identified SCI with paralysis as a significant risk factor for development of VTE (odds ratio: 3.39).

A 5-year retrospective review from one trauma institution (13) identified 4 injury patterns that accounted for 92% of pulmonary emboli: SCI with paraplegia or tetraplegia, severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) with a Glasgow Coma Scale score (GCS) of 8 or less, isolated long bone fractures in patients older than 55 years of age, and complex pelvic fractures associated with long bone fractures. The relative risk of PE in patients with SCI was 54 times that of the general trauma population without identifiable risk factors, the highest of all the high-risk groups. The incidence of PE was 25 in 2,525 admitted trauma patients (1% incidence) during the review period. Another review of 9,721 trauma patients showed that the high-risk categories include TBI plus SCI, TBI plus long bone fracture, severe pelvic fracture plus long bone injury, and multiple long bone fractures (14).

VENOUS THROMBOEMBOLISM PROPHYLAXIS

Several guidelines have been published detailing recommended VTE prophylaxis regimens after an acute SCI (1,15,16). According to the Seventh American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) Conference on Antithrombotic and Thrombolytic Therapy (1), all patients with acute SCI should receive thromboprophylaxis. Low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) has been recommended as the preferred agent when hemostasis is evident. When LMWH is contraindicated, which is common early after injury, mechanical prophylaxis with intermittent pneumatic compression (IPC) devices and/or graduated compression stockings are recommended. However, IPC and graduated compression stockings are both considered by this consensus panel as inferior prophylaxis options, and a strong recommendation against their use as single prophylaxis modalities is also made. The ACCP guidelines also recommend against the use of a vena cava filters (VCFs) as primary prophylaxis. However, some debate exists regarding the data and references cited in reaching this conclusion, which are discussed later in this report.

According to the Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine's Clinical Practice Guidelines published in 1997 (16), VCF placement is indicated in patients with SCI who have failed anticoagulant prophylaxis or who have a contraindication to anticoagulation, such as active or potential bleeding sites not amenable to local control. Additionally, the guidelines state that VCFs should be considered in patients with complete motor paralysis caused by lesions in the high cervical cord (C2 and C3), with poor cardiopulmonary reserve, or with thrombus in the inferior vena cava (IVC) despite anticoagulant prophylaxis. The recommendations were based on non-randomized studies with historic controls and had a moderate consensus of expert opinion from the consortium panel members. They also commented specifically that the VCF is not a substitute for VTE prophylaxis and that VTE prophylaxis should be commenced as soon as feasible.

In 2002, the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma (EAST) analyzed the available medical literature and set forth guidelines regarding prophylactic VCF insertion in high-risk injured patients (15). Cross-referencing "vena cava filters" with "trauma," 31 references were identified in a MEDLINE search. Although there were no Class 1 data (large, well-designed prospective randomized trials) to support prophylactic VCF insertion in high-risk injured patients, there were some Class 2 and Class 3 data to support the recommendation for the consideration of VCF insertion in high-risk patients who cannot receive prophylactic doses of anticoagulation. Contraindications for anticoagulation include brain hemorrhage, solid organ injuries, or any injury in which the risk of further hemorrhage is too great for even prophylactic doses of anticoagulation. The high-risk criteria include TBI (GCS, 8), SCI, TBI plus long bone fractures, severe pelvic fracture plus long bone fracture, and multiple long bone fractures.

At first glance, it seems that the EAST guidelines conflict with the American College of Chest Physicians' Evidence-Based Guidelines for SCI thromboprophylaxis, which recommends against the use of a VCF as primary prophylaxis against PE. The ACCP recommendation is primarily based on the potential risks of VCFs and the costs associated with placement of these devices. The EAST guidelines recommend consideration of VCF insertion in patients considered hemorrhagic risks to even prophylactic doses of LMWH (ie, not as primary prophylaxis). The PE risk is highest in the acute postinjury phase, which is also the time when the hemorrhagic risks (concomitant solid organ injuries, brain injuries) are the greatest, thus contraindicating anticoagulant prophylaxis. The clinician must also weigh the risk of anticoagulant prophylaxis to the SCI itself. In the thoracic region, the loss of an additional spinal cord level may not be clinically significant; however, the extension of a single cervical or lumbar level caused by hemorrhage is likely to be functionally significant.

The complication rates in SCI cited in the ACCP statement are misleading because they are depicted as high complication rates but are, overall, very small numbers (17). The same misuse of statistics was exposed by Rogers et al (18) in responding to a report titled, "Routine Prophylactic Vena Cava Filtration is not Indicated after Spinal Cord Injury," published in the Journal of Trauma in 2002 (19). The conclusions of this analysis provided no confidence intervals, and the results were in stark contrast to a meta-analysis by Velmahos et al (20), who confirmed that patients with SCI trauma are at highest risk for venous thromboembolism.

VENA CAVA FILTERS

Interruption of the IVC with a mechanical barrier to prevent PE was first suggested by Trousseau in 1868 (21). The procedure gained significant clinical application with the introduction of the Greenfield stainless steel VCF in 1973 (21). The Greenfield filter was a marked improvement over the previous models in its enhanced clot-trapping capability and reduced rates of caval occlusion. Continued advances in filter designs have led to a dramatic increase in their use—from 2,000 in 1979 to 49,000 in 1999 in the United States (22). This has skyrocketed to more than 140,000 VCFs inserted worldwide in 2003 (23).

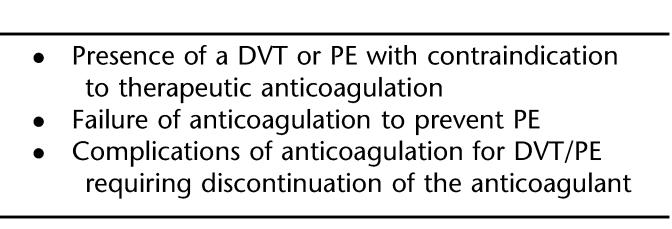

The most striking trend in vena cava filtration over the past decade has been the increase in the use of "prophylactic" VCFs (22). In 1999, 45% of VCFs were used in patients with DVT alone, 36% were in patients with PE, and presumably 19% were used for prophylaxis. Technically, all VCFs are prophylactic in that they do not treat PE or DVT but are intended to prevent further thrombi from traveling to the lungs. The classic indications for VCFs include the presence of DVT and/or PE (Table 1). Relative indications for VCF include a free-floating ileofemoral thrombus concurrent with pulmonary thrombectomy, thrombolysis of lower extremity DVT, and patients with limited cardiopulmonary reserve who otherwise "could not tolerate" even a small PE. The latter indication is different from the others in that there is no documented DVT or PE; therefore, it is truly a prophylactic indication. Because the ease of use and safety profile of VCFs have improved, the prophylactic use of VCFs in patients without a documented acute DVT or PE has increased. The trauma population has been the patient group most often receiving prophylactic VCFs (14,22,24,25).

Table 1.

Classic Indications for VCFs

The use of a VCF for PE has been advocated in the trauma population, which includes persons with SCI (24,26–28). Most medical literature concerning VCF use after SCI involves persons with SCI of traumatic rather than nontraumatic etiology. This review, therefore, focuses primarily on this group.

VCF EFFICACY AND COMPLICATIONS

It is well established that VCFs are efficacious. They prevent PE from lower-extremity DVT at a rate of about 98% (29). Jarrell et al (26) studied 21 Greenfield filters placed in patients with SCI with DVT or PE and reported 1 death caused by PE after filter placement.

In a meta-analysis of trauma literature on prevention of VTE after injury, Velmahos et al (20) stated that spinal fractures and SCI increase the risk for development of DVT twofold and threefold, respectively, compared with the rest of the trauma population. In the same report, patients with prophylactically placed VCFs had a lower incidence of PE (0.2%) compared with concurrently managed patients without VCFs (1.5%) or historical controls without VCFs (5.8%). These data were obtained mostly from uncontrolled and nonrandomized studies, however, and do not allow firm conclusions to be drawn about VCFs.

Wojcik et al (30) reported on their follow-up (mean of 28.9 months) of 105 trauma patients with VCFs placed at their institution between 1993 and 1997. Forty-one filters were placed in patients with DVT or PE; 64 were placed in patients for prophylactic indications per the guidelines developed by EAST (31). There were no clinically significant complications related to insertion of VCFs, and no PE was detected after VCF insertion.

In a 5-year review of prophylactic VCFs at their institution during the first half of the 1990s, Wilson et al (28) placed VCFs in 15 patients with SCI who were concurrently treated with either low-dose heparin or IPCs. None had a PE during a 1-year follow-up period. The 1-year caval patency rate was 81.8%. The authors reported that their results were superior to those in a historical cohort treated without VCFs, of whom 7 of 111 cohort patients had a PE; however, 6 of the 7 were not receiving concurrent VTE prophylaxis at the time of their PE.

In 1998, Rogers et al (32) reported their 5-year follow-up experience with prophylactic VCFs in high-risk trauma patients with diagnoses including SCI, severe fractures of the pelvis or long bone (or both), and severe TBI and a contraindication to anticoagulation. There was a 3.1% rate of asymptomatic insertion-related DVT. The caval patency rate was 97% after 1, 2, and 3 years.

Before the report by Duperier et al (33), no other study had investigated thrombotic complications exclusively in trauma patients before and after VCF insertion. This study is unique because of the large number of filters placed within 1 year at one institution and the large number of duplex examinations obtained before and after VCF placement. One hundred thirty-three patients received a VCF through a percutaneous approach. Of these, 16 had SCI and 3 had vertebral fractures. Filters were inserted an average of 6.8 days after trauma. Indications for filter placement included development of DVT despite prophylaxis or contraindications to anticoagulation. All patients received IPC devices and/or graduated stockings when not precluded by external fixation devices. Prophylactic LMWH was administered except in patients with closed head trauma or SCI. A new DVT was diagnosed after VCF placement in 26% of the 58 patients who had both the pre- and postinsertion duplex scans. Of these, only 4 DVTs were located solely in the ipsilateral extremity, and 3 were in both extremities. Sing et al (34) identified 8 DVTs in 158 patients with filters; 2 of these occurred at the insertion site. These data suggest that the VCF does not directly cause insertion site thrombosis. In theory, the percutaneous technique is less likely than the open technique to cause thrombus formation, because it does not require a suture line. Other acute complications of VCF placement include local hematoma (35), strut malposition, and filter tilt (36). Chronic complications include caval thrombosis (14) and chronic venous insufficiency (37).

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS IN CERVICAL SCI

Previous studies have identified problems associated with IVC filtration when the original stainless steel Greenfield VCF was used in patients with tetraplegia (38,39). In the largest series consisting of 13 patients with tetraplegia who had VCFs placed after documented DVT or PE, 11 of the patients had follow-up abdominal radiographs (mean, 75 weeks after insertion). Five patients had abnormalities related to the Greenfield filter, and 4 of these were caudal migration of the filter. The majority of the patients in this study had been treated with assisted cough and the authors hypothesized that these maneuvers exert significant forces on the vena cava and filter, potentially leading to filter migration and vena cava perforation. Only one patient in this report had radiographic indication of one of the filter's struts having penetrated the caval wall; however, the patient remained without symptoms over the ensuing 5-year period (38).

Similarly, Kinney et al (40) suggested in their series of 11 patients that acute cervical SCI and the associated supportive care may be associated with an increased risk of complications after prophylactic IVC filter use. They observed that filter migration was the most common complication (5 patients), followed by vena caval thrombus formation (2 patients) and caval perforation (1 patient).

A survey conducted of 136 Level 1 trauma centers (63% survey response rate) during the late 1990s by Maxwell et al (19) revealed that 124 of the centers routinely provided care for patients with acute SCI. Among the centers, 56 (45.2%) placed prophylactic IVC filters in greater than 50% of their patients with acute SCI. In the same survey, 82 centers (66.1%) also routinely used IPCs, 71 (57.3%) used LMWH, and 17 (13.7%) used heparin; 83 (66.9%) centers used routine venous Doppler ultrasound screening.

Quirke et al (24) also completed a survey of 210 US trauma centers and found that VCF insertion was performed by radiologists at 81% of the centers, trauma surgeons at 34%, vascular surgeons at 33%, and general surgeons at 13%. Respondents agreed that absolute indications for VCFs were PEs while on anticoagulation (93%), presence of DVT and contraindication for anticoagulation (89%), and free-floating ileofemoral thrombus by venogram (54%) and duplex imaging (45%). Relative indications were DVT by duplex imaging (41%) or venogram (38%), SCI (40%), pelvic fractures (39%), multiple lower extremity fractures (29%), concurrent cancer (19%), prolonged bed rest (14%), and obesity (10%). Respondents also stated that VCF removability would significantly increase prophylactic placement from 40% to 53% in persons with SCI.

OPTIONAL VENA CAVA FILTERS

Notwithstanding the good safety profiles for VCFs, concerns remain regarding the use of prophylactic VCFs in subjecting patients with a relatively defined period of thromboembolic risk to the possible long-term complications of a permanent device (24). Of these complications, caval occlusion is the most important. Acute caval occlusion is likely the result of thrombus trapping, an otherwise fatal event. Chronic caval occlusion is theorized to occur from the slow intimal overgrowth of the device. The clinical support for this theory is that acute occlusions commonly result in hemodynamic compromise (decreased venous return) and leg swelling. Chronic occlusions (slowly evolving) allow for the development of venous collaterals and frequently are asymptomatic (41).

Whatever the case, these concerns may be addressed by the development of removable or "optional" filters. In theory, the patients are protected during the high-risk period, and the VCF can be removed at a later time when the high-risk period is over, thus removing the long-term risk of the VCF. Moreover, in cases of contraindication to therapeutic anticoagulation, the filter can be removed when the contraindication has subsided and therapeutic anticoagulation can be started.

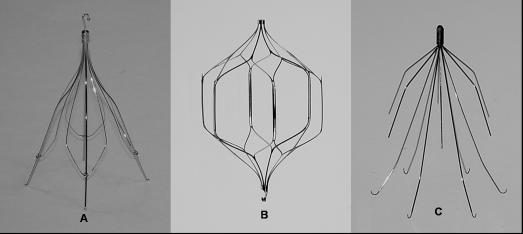

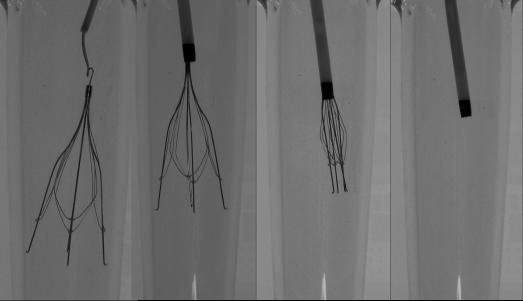

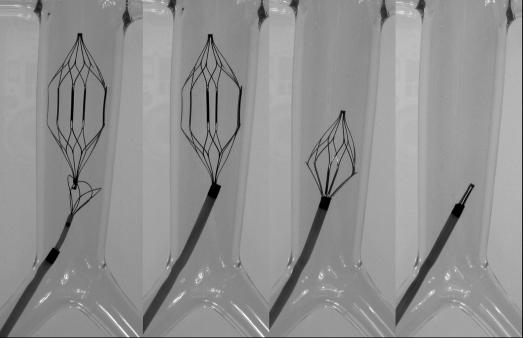

Three optional VCFs are now available and approved by the Food and Drug Administration (Figure 1). All 3 devices were introduced for permanent implantation; however, over the past 2 years, retrieval has been added to their approved information for use. These filters are retrieved using endovascular techniques. The Günther Tulip (Cook Inc., Bloomington, IL) and the OptEase (Cordis Endovascular, Warren, NJ) are retrieved using an endovascular snare grasping a hook on the end of the filter. The filters are withdrawn into a sheath and removed. The Recovery (CR Bard Inc., Murray Hill, NJ) is retrieved with a designated cone that engages the tip of the filter, collapses the struts, and can be withdrawn into an introducer sheath.

Figure 1. (A) Günther Tulip. (B) OptEase. (C) Recovery.

Günther Tulip

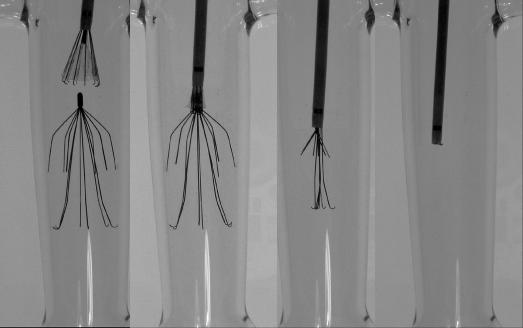

The Günther Tulip has a conical-shaped design (similar to the Greenfield filter) and can be inserted percutaneously through the femoral or jugular approach using an 8.5F introducer sheath. The retrieval technique for the Tulip is through the jugular vein using an endovascular snare, which grasps a hook located on the apex of the filter (Figure 2). After snaring, the filter is pulled into an 8F or larger sheath. The early retrieval experience from the Registry of the Canadian Interventional Radiology Association recommended a limited duration of implantation to 15 days (42). There were early reports extending the implantation intervals by repositioning the filter endo-vascularly at 15-day intervals (43,44). More recent experience has shown that retrievals can be safely accomplished after extended periods of implantation (42,45,46).

Figure 2. Retrieval of a Günther Tulip VCF using a gooseneck snare.

Optease

The OptEase is a modification of an earlier design, the TrapEase filter (Cordis Endovascular). This device has a biconvex design, which gives the filter 2 levels of filtration. The TrapEase has a symmetric design with barbs in both directions that allows for insertion without concern for direction. The OptEase modification added a double hook on the caudal end and unidirectional barbs. This filter must be inserted with the hook caudally. Approved for caval diameters up to 30 mm, it can be inserted through the jugular, femoral, and antecubital approaches using its 6F introducer.

The retrieval technique for the OptEase is similar to the Tulip using an endovascular snare, but is through the femoral route (Figure 3). The recommended duration of implantation is 23 days.

Figure 3. Retrieval of an OptEase VCF using an Ensnare (InterV, Gainesville, FL).

Recovery

The Recovery was the first filter approved for retrieval in the United States by the FDA (2003). A modification of the Simon Nitinol filter, it also has 2 levels of filtration. Presently only available in a femoral insertion kit, a jugular insertion kit is in the final stages of clearance by the FDA. Endovascular retrieval of this filter is accomplished using a dedicated retrieval cone (CR Bard, Inc.). This cone has inward-facing wires covered by a urethane sheath, which aids in guiding the tip of the filter into the retrieval sheath. The inward wires aid in securely grasping the apex of the filter (Figure 4). There is no recommended limit on implantation duration for the Recovery, and several studies have reported uneventful retrievals after more than 100 days, with the longest implant by one of the authors (RFS) being greater than 500 days.

Figure 4. Retrieval of a Recovery VCF using the Recovery Cone (CR Bard Inc.).

CLINICAL DATA

The present literature on the use of optional VCFs is limited. Many, if not all, of these studies focus on the feasibility of removing the filters. Of the 3 optional filters, the Tulip has the most published data regarding both permanent implantation and retrieval (42–45,47–50). Much of the clinical data concerning retrievable VCFs examined their use in trauma patients. Offner et al (50) placed optional filters in 44 critically ill patients (37 trauma patients). There were no complications associated with filter insertion or removal. Three filters could not be removed, 2 because of trapped thrombus and 1 for technical reasons. Rosenthal et al (51) placed 94 OptEase filters under ultrasound guidance in trauma patients. One patient developed a PE after filter retrieval. Thirty-one patients underwent uneventful filter retrieval. Three patients had significant trapped thrombus that prevented their filters from being removed. Forty-one filters were not removed because of a continuing contraindication to anticoagulation. Hoff et al (43) inserted 35 Günther Tulip filters in patients with high-risk orthopedic injuries. VCFs were removed in 18 patients (51%) without complications. Similarly, Morris et al (44) reported 136 trauma and nontrauma patients who received Tulip filters. Twenty-two were repositioned or removed. One major complication was recorded, a nonfatal PE, which occurred after removal. Allen et al (49) reported 53 filters (Günther Tulip) in 51 trauma patients.

Overall, these studies show the safety and feasibility of retrievable filters in injured patients. Objective criteria for the appropriate timing of removal (or the decision to leave the filter as a permanent device) need to be defined and are presently being evaluated.

CONCLUSION

Patients with SCI have been repeatedly identified as a high-risk population for VTE. Pharmacologic (LMWHs) and mechanical techniques (IPC) remain the primary prophylaxis against VTE. However, in the acute setting, the consideration of VCFs in patients with early contra-indication to even prophylactic doses of LMWH may be reasonable. This consideration has support in the medical literature. Continued advancements in VCFs, most notably the ability to remove them, have dramatically increased their "prophylactic" use. The ability to retrieve filters once the highest PE risk has resolved offers patients the benefit of the filter without its long-term risks. Large, preferably multicenter, trials are necessary to show a benefit of this practice. Future research should evaluate the impact of filter retrieval on the outcome of both the prophylaxis against PE and the impact on the long-term complications of optional filters that are removed compared with filters left as a permanent device.

Acknowledgments

We thank Cissy Moore-Swartz for assistance editing this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Geerts WH, Pineo GF, Heit JA, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism: the Seventh ACCP Conference on Antithrombotic and Thrombolytic Therapy. Chest. 2004;126(suppl 3):338S–400S. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.3_suppl.338S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirshblum S. Rehabilitation of spinal cord injury. In: DeLisa JA, Gans BM, editors. Rehabilitation Medicine: Principles and Practice. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005. pp. 1715–1751. [Google Scholar]

- El Masri WS, Silver JR. Prophylactic anticoagulant therapy in patients with spinal cord injury. Paraplegia. 1981;19:334–342. doi: 10.1038/sc.1981.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naso F. Pulmonary embolism in acute spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1974;55:275–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinley WO, Jackson AB, Cardenas DD, et al. Long-term medical complications after traumatic spinal cord injury: a regional model systems analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;80:1402–1410. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(99)90251-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinley WO, Tewksbury MA, Godbout CJ. Comparison of medical complications following nontraumatic and traumatic spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2002;25:88–93. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2002.11753607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudson MM, Collins JA, Goodman SB, McRory DW. Thromboembolism following multiple trauma. J Trauma. 1992;32:2–11. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199201000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudson MM, Lewis FR, Clinton A, Atkinson K, Megerman J. Prevention of venous thromboembolism in trauma patients. J Trauma. 1994;37:480–487. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199409000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers FB. Venous thromboembolism in trauma patients: a review. Surgery. 2001;130:1–12. doi: 10.1067/msy.2001.114558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geerts WH, Code KI, Jay RM, Chen E, Szalai JP. A prospective study of venous thromboembolism after major trauma. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1601–1606. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199412153312401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shackford SR, Davis JW, Hollingsworth-Frielund P, et al. Venous thromboembolism in patients with major trauma. Am J Surg. 1990;159:365–369. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)81272-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudson MM, Ikossi DG, Khaw L, Morabito D, Speetzen LS. Thromboembolism after trauma: an analysis of 1602 episodes from the American College of Surgeons National Data Bank. Ann Surg. 2004;240:490–498. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000137138.40116.6c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz DJ, Brasel KJ, Washington L, et al. Incidence of asymptomatic pulmonary embolus in moderately to severely injured trauma patients. J Trauma. 2004;56:727–733. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000119687.23542.ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers FB, Shackford SR, Wilson J, Ricci MA, Morris CS. Prophylactic vena cava filter insertion in severely injured trauma patients: indications and preliminary results. J Trauma. 1993;35:637–642. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199310000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez JL, Lopez JM, Proctor MC, et al. Early placement of prophylactic vena caval filters in injured patients at high risk for pulmonary embolism. J Trauma. 1996;40:797–804. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199605000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers FB, Cipolle MD, Velmahos G, Rozycki G, Luchette FA. Practice management guidelines for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in trauma patients: the EAST Practice Management Guidelines Work Group. J Trauma. 2002;53:142–164. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200207000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine. Prevention of thromboembolism in spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 1997;20:259–283. doi: 10.1080/10790268.1997.11719479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield LJ. Does cervical spinal cord injury induce a higher incidence of complications after prophylactic Greenfield filter usage? J Vasc Intervent Radiol. 1997;8:719–720. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(97)70650-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers FB, Osler TM, Sing RF. Pulmonary embolism (letter) J Trauma. 2002;53:1032–1034. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000031941.42769.B1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell RA, Chavarria-Aguilar M, Cockerham WT, et al. Routine prophylactic vena cava filtration is not indicated after acute spinal cord injury. J Trauma. 2002;52:902–906. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200205000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velmahos GC, Kern J, Chan LS, Oder D, Murray JA, Shekelle P. Prevention of venous thromboembolism after injury: an evidence-based report—part II: analysis of risk factors and evaluation of the role of vena caval filters. J Trauma. 2000;49:140–144. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200007000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield LJ, McCurdy JR, Brown PP, Elkins RC. A new intracaval filter permitting continued flow and resolution of emboli. Surgery. 1973;73:599–606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oschner A, Oschner JK, Saunders HS. Prevention of pulmonary embolism by caval ligation. Ann Surg. 1970;171:923–938. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197006010-00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein PD, Kayali F, Olson RE. Twenty-one year trends in the use of inferior vena cava filters. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1541–1545. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.14.1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IMS HSI Database. Available at: www.IMSHealth.com. Accessed April 15, 2006.

- Quirke TE, Ritota PC, Swan KG. Inferior vena caval filter use in U.S. trauma centers: a practitioner survey. J Trauma. 1997;43:333–337. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199708000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers FB, Shackford SR, Ricci MA, Wilson JT, Parsons S. Routine prophylactic vena cava filter insertion in severely injured trauma patients decreases the incidence of pulmonary embolism. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;180:641–647. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrell BE, Posuniak E, Roberts J, Osterholm J, Cotler J, Ditunno J. A new method of management using the Kim-Ray Greenfield filter for deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in spinal cord injury. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1983;157:316–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khansarinia S, Dennis JW, Veldenz HC, Butcher JL, Hartland L. Prophylactic Greenfield filter placement in selected high-risk trauma patients. J Vasc Surg. 1995;22:231–236. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(95)70135-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JT, Rogers FB, Wald SL, Shackford SR, Ricci MA. Prophylactic vena cava filter insertion in patients with traumatic spinal cord injury: preliminary results. Neurosurgery. 1994;35:234–239. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199408000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield LJ, Proctor MC. Recurrent thromboembolism in patients with vena cava filters. J Vasc Surg. 2001;33:510–514. doi: 10.1067/mva.2001.111733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojcik R, Cipolle MD, Fearen I, Jaffe J, Newcomb J, Pasquale MD. Long-term follow-up of trauma patient with a vena caval filter. J Trauma. 2000;49:839–843. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200011000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquale M, Fabian TC. Practice management guidelines for trauma from the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma. J Trauma. 1998;44:941–957. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199806000-00001. EAST Ad Hoc Committee on Practice Management Guideline Development. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers FB, Strindberg G, Shackford SR, et al. Five-year follow up of prophylactic vena cava filters in high-risk trauma patients. Arch Surg. 1998;133:406–412. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.133.4.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duperier T, Mosenthal A, Swan K, Kaul S. Acute complications associated with Greenfield filter insertion in high-risk trauma patients. J Trauma. 2003;54:545–549. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200303000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sing RF, Jacobs DG, Heniford BT. Bedside insertion of vena cava filters in the intensive care unit. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;192:570–576. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(01)00837-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aswad MA, Sandager GP, Pais S, et al. Early duplex scan evaluation of four vena caval interruption devices. J Vasc Surg. 1996;24:809–818. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(96)70017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker DM, Philbrick JT, Selby B. Inferior vena caval filters, indications, safety, effectiveness. Arch Intern Med. 1992;152:1985–1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield LJ, Proctor MC, Michaels AJ, Taheri PA. Prophylactic vena caval filters in trauma: the rest of the story. J Trauma. 2000;32:490–497. doi: 10.1067/mva.2000.108636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balshi JD, Cantelmo NL, Menzoian JO. Complications of caval interruption by Greenfield filter in quadriplegics. J Vasc Surg. 1989;9:558–562. doi: 10.1067/mva.1989.vs0090558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidawy AN, Menzoian JO. Distal migration and deformation of the Greenfield vena cava filter. Surgery. 1986;99:369–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinney TB, Rose SC, Valji K, Oglevie SB, Roberts AC. Does spinal cord injury induce a higher incidence of complications after prophylactic Greenfield inferior vena cava filter usage. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1996;7:907–915. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(96)70869-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sing RF, Rogers FB, Novitsky YW, Heniford BT. Optional vena cava filters for patients with high thromboembolic risk: questions to be answered. Surg Innov. 2005;12:195–202. doi: 10.1177/155335060501200303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millward SF, Oliva VL, Bell SD, et al. Gunther Tulip retrievable vena cava filter: results from the Registry of the Canadian Interventional Radiology Association. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2001;12:1053–1058. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(07)61590-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoff WS, Hoey BA, Wainwright GA, et al. Early experience with retrievable inferior vena cava filters in high-risk trauma patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;199:869–874. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2004.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris CS, Rogers FB, Najarian KE, Bhave AD, Shackford SR. Current trends in vena cava filtration with the introduction of a retrievable filter at a level I trauma center. J Trauma. 2004;57:32–36. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000135497.10468.2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binkert CA, Bansal A, Gates JD. Inferior vena cava filter removal after 317-day implantation. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2005;16:395–398. doi: 10.1097/01.RVI.0000150029.86869.DE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kachura JR. Inferior vena cava filter removal after 475-day implantation. J Vasc Intervent Radiol. 2005;16:1156–1158. doi: 10.1097/01.RVI.0000173279.32274.BD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terhaar OA, Lyon SM, Given MF, Foster AE, McGrath F, Lee MJ. Extended interval for retrieval of Gunther Tulip filters. J Vasc Intervent Radiol. 2004;15:1257–1262. doi: 10.1097/01.RVI.0000134497.50590.E2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wicky S, Doenz F, Meuwly JY, Portier F, Schnyder P, Denys A. Clinical experience with retrievable Gunther Tulip vena cava filters. J Endovasc Ther. 2003;10:994–1000. doi: 10.1177/152660280301000524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen TL, Carter JL, Morris BJ, Harker CP, Stevens MH. Retrievable vena cava filters in trauma patients for high-risk prophylaxis and prevention of pulmonary embolism. Am J Surg. 2005;189:656–661. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Offner PJ, Hawkes A, Madayag R, Seale F, Maines C. The role of temporary inferior vena cava filters in critically ill surgical patients. Arch Surg. 2003;138:591–595. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.138.6.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal D, Wellons ED, Levitt AB, Shuler FW, O'Conner RE, Henderson VJ. Role of prophylactic temporary inferior vena cava filters placed at the ICU bedside under intravascular ultrasound guidance in patients with multiple trauma. J Vasc Surg. 2004;40:958–964. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2004.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]