Abstract

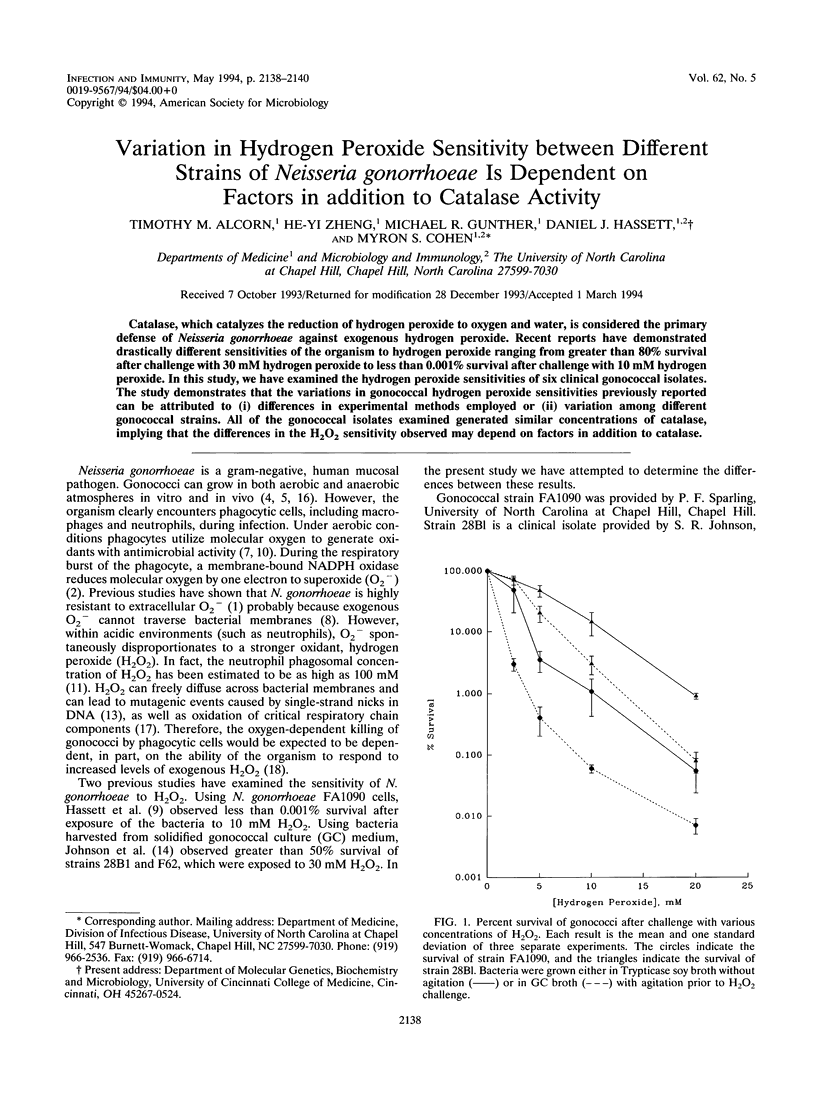

Catalase, which catalyzes the reduction of hydrogen peroxide to oxygen and water, is considered the primary defense of Neisseria gonorrhoeae against exogenous hydrogen peroxide. Recent reports have demonstrated drastically different sensitivities of the organism to hydrogen peroxide ranging from greater than 80% survival after challenge with 30 mM hydrogen peroxide to less than 0.001% survival after challenge with 10 mM hydrogen peroxide. In this study, we have examined the hydrogen peroxide sensitivities of six clinical gonococcal isolates. The study demonstrates that the variations in gonococcal hydrogen peroxide sensitivities previously reported can be attributed to (i) differences in experimental methods employed or (ii) variation among different gonococcal strains. All of the gonococcal isolates examined generated similar concentrations of catalase, implying that the differences in the H2O2 sensitivity observed may depend on factors in addition to catalase.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Archibald F. S., Duong M. N. Superoxide dismutase and oxygen toxicity defenses in the genus Neisseria. Infect Immun. 1986 Feb;51(2):631–641. doi: 10.1128/iai.51.2.631-641.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BEERS R. F., Jr, SIZER I. W. A spectrophotometric method for measuring the breakdown of hydrogen peroxide by catalase. J Biol Chem. 1952 Mar;195(1):133–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babior B. M., Curnutte J. T., Kipnes B. S. Pyridine nucleotide-dependent superoxide production by a cell-free system from human granulocytes. J Clin Invest. 1975 Oct;56(4):1035–1042. doi: 10.1172/JCI108150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark V. L., Knapp J. S., Thompson S., Klimpel K. W. Presence of antibodies to the major anaerobically induced gonococcal outer membrane protein in sera from patients with gonococcal infections. Microb Pathog. 1988 Nov;5(5):381–390. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(88)90038-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen M. S., Chai Y., Britigan B. E., McKenna W., Adams J., Svendsen T., Bean K., Hassett D. J., Sparling P. F. Role of extracellular iron in the action of the quinone antibiotic streptonigrin: mechanisms of killing and resistance of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1987 Oct;31(10):1507–1513. doi: 10.1128/aac.31.10.1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen M. S., Sparling P. F. Mucosal infection with Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Bacterial adaptation and mucosal defenses. J Clin Invest. 1992 Jun;89(6):1699–1705. doi: 10.1172/JCI115770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassett D. J., Britigan B. E., Svendsen T., Rosen G. M., Cohen M. S. Bacteria form intracellular free radicals in response to paraquat and streptonigrin. Demonstration of the potency of hydroxyl radical. J Biol Chem. 1987 Oct 5;262(28):13404–13408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassett D. J., Charniga L., Cohen M. S. recA and catalase in H2O2-mediated toxicity in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Bacteriol. 1990 Dec;172(12):7293–7296. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.12.7293-7296.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassett D. J., Cohen M. S. Bacterial adaptation to oxidative stress: implications for pathogenesis and interaction with phagocytic cells. FASEB J. 1989 Dec;3(14):2574–2582. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.3.14.2556311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurst J. K., Barrette W. C., Jr Leukocytic oxygen activation and microbicidal oxidative toxins. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 1989;24(4):271–328. doi: 10.3109/10409238909082555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imlay J. A., Linn S. Bimodal pattern of killing of DNA-repair-defective or anoxically grown Escherichia coli by hydrogen peroxide. J Bacteriol. 1986 May;166(2):519–527. doi: 10.1128/jb.166.2.519-527.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imlay J. A., Linn S. DNA damage and oxygen radical toxicity. Science. 1988 Jun 3;240(4857):1302–1309. doi: 10.1126/science.3287616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson S. R., Steiner B. M., Cruce D. D., Perkins G. H., Arko R. J. Characterization of a catalase-deficient strain of Neisseria gonorrhoeae: evidence for the significance of catalase in the biology of N. gonorrhoeae. Infect Immun. 1993 Apr;61(4):1232–1238. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.4.1232-1238.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klotz M. G., Hutcheson S. W. Multiple periplasmic catalases in phytopathogenic strains of Pseudomonas syringae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992 Aug;58(8):2468–2473. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.8.2468-2473.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp J. S., Clark V. L. Anaerobic growth of Neisseria gonorrhoeae coupled to nitrite reduction. Infect Immun. 1984 Oct;46(1):176–181. doi: 10.1128/iai.46.1.176-181.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohen R., Chevion M. Cytoplasmic membrane is the target organelle for transition metal mediated damage induced by paraquat in Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 1988 Apr 5;27(7):2597–2603. doi: 10.1021/bi00407a049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng H. Y., Hassett D. J., Bean K., Cohen M. S. Regulation of catalase in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Effects of oxidant stress and exposure to human neutrophils. J Clin Invest. 1992 Sep;90(3):1000–1006. doi: 10.1172/JCI115912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]