Abstract

Background/Objective:

Chronic pain is common in patients with spinal cord injury (SCI). Any new strategy that is effective in treating this problem would be welcomed by this patient population.

Methods:

A case series is presented of SCI with neuropathic pain. In these 3 cases, interventional spine therapy is used as a diagnostic and/or therapeutic tool in the management of pain.

Results:

In the cases presented, interventional spine therapy proved useful in identifying the patient's pain generator. In most cases, the intervention was effective in reducing pain for a long enough period to serve as an effective pain management strategy. Other associated problems, such as spasticity, were similarly reduced.

Conclusion:

Interventional spine therapy should be considered as a tool in the armamentarium of any SCI physician managing their patient's chronic pain.

Keywords: Spinal cord injuries, Neuropathic pain, Epidural injection, Pain management

INTRODUCTION

Chronic pain, a frequent complication of spinal cord injury (SCI), impairs rehabilitation and quality of life. SCI professionals need to be knowledgeable about pain management and open to novel methods of pain relief. In this series of 3 patients with neuropathic pain that was poorly controlled by traditional means, epidural administration of pain medication provided prolonged relief. Interventional spine therapy offers another means of managing chronic pain in this population, and may relieve spasticity and prevent autonomic dysreflexia as well.

Case 1

A previously healthy 37-year-old woman sustained an L2 burst fracture in a motor vehicle crash. She required an L2 to L3 decompression and a left lateral fusion with an L1 to L5 posterior spinal fusion, with hardware including two fusion rods and cerclage wires for stabilization. The grade of impairment was an American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) T10 Grade A with a zone of incompletion through L3. Strength testing (right/left) was 5/4 for hip flexors, 5/5 for knee extensors, 2/2 for knee flexors, 2/2 for hip abduction, 5/5 for hip adduction, and absent in ankles and toes. Deep tendon reflexes were trace at the knees and absent at the ankles. Lumbar disk space heights were initially well maintained.

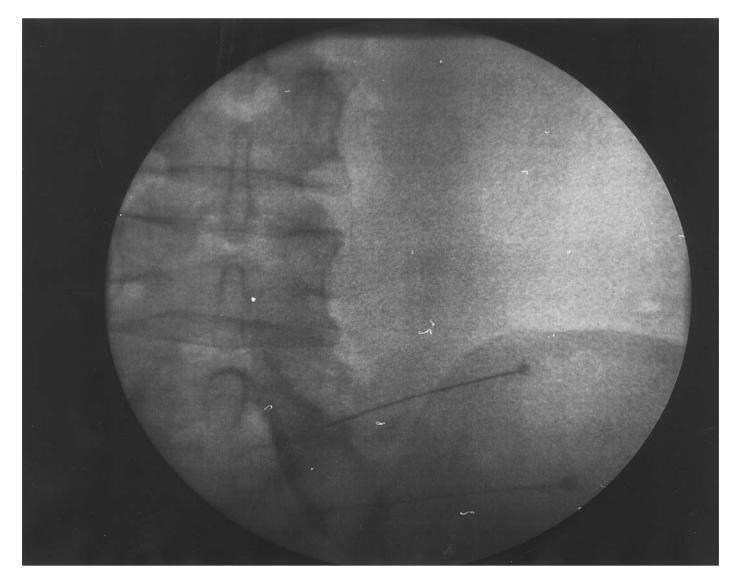

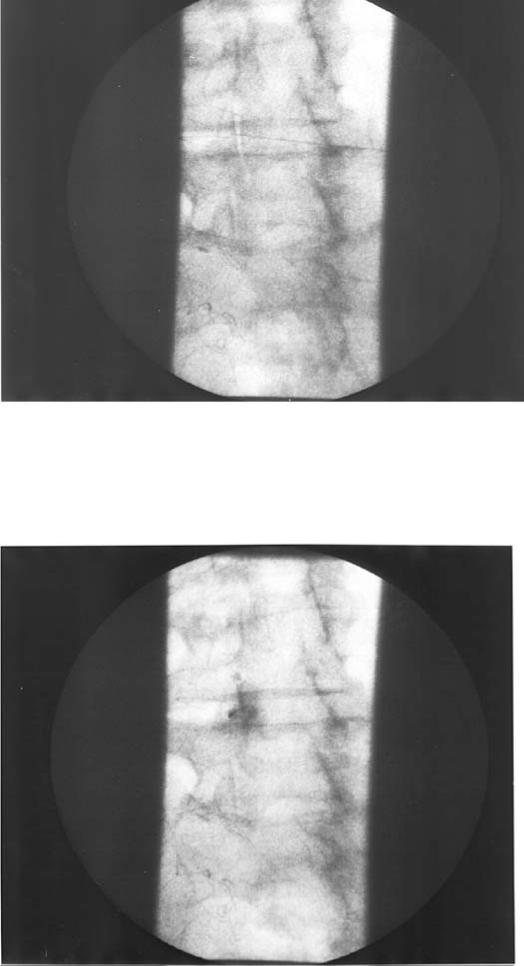

Six years later, the patient complained of progressive left lower extremity pain, which improved with standing and worsened with prolonged sitting. Her neurological examination was unchanged. Past medical history was significant for a pituitary adenoma with hypopituitarism. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the lumbar spine revealed severe L4–L5 facet hypertrophy with lateral recess stenosis and L5–S1 disk degeneration without bulge with mild facet hypertrophy without stenosis. Left L4–L5 and L5–S1 transforaminal epidural injections (Figure 1), each with 1 mL of 1% lidocaine and 1 mL of 40 mg/mL Depo Medrol, resulted in many months of decreased left leg pain. A repeat injection 12 months later again resulted in a marked decrease in pain for 2 months. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication relieved her pain significantly, but not as well as the initial epidural injection. Left L4–L5 intra-articular facet block (Figure 2) with left L5–S1 transforaminal epidural injection with lidocaine and Depo Medrol resulted in complete resolution of left leg pain for at least 6 months, allowing her to discontinue all narcotic, anti-inflammatory and neuropathic pain medications.

Figure 1. A right L5–S1 transforaminal and right S1 foraminal epidural injection. Injection contrast highlights the L5 and S1 nerve roots with epidural flow.

Figure 2. A left L4–L5 intra-articular facet block. The top radiograph shows the needle in the joint, the bottom radiograph shows the injection of omnipaque. An arthrogram indicated the vertical placement of dye (the blob of dye in the middle of the bottom picture that occurred with initial dye injection, showing the needle posterior to the joint capsule).

Case 2

A previously healthy 36-year-old man sustained an L1 burst fracture in a motor vehicle accident, requiring an L1 laminectomy and decompression with T12 to L1 posterior spinal fusion. The ASIA grade of impairment was T12 Grade A. He continued to have problems with back pain and right back spasms without relief from physical therapy, botulinum toxin A injections, and morphine pump. MRI examination revealed a right T9–T10 paracentral disk bulge. Transforaminal epidural injection with 1 mL of 1% lidocaine and 1 mL of 80 mg/mL Depo Medrol at that level resulted in a marked decrease in right back pain and spasm, allowing for discontinuation of all oral pain medication.

Case 3

A 31-year-old man was healthy until he sustained a T8 fracture-dislocation in a motor vehicle crash, requiring a T7 to T11 posterior fixation with T7 to T12 laminar hooks, and a T9 to T10 iliac crest bone graft. The ASIA grade of impairment was T7 Grade A. The patient presented with left chest wall pain. Physical examination revealed that pin sensation was intact to T10 on the right and T7 on the left with dysesthesias noted on the left at T8 and T9. Computed tomography (CT) myelogram revealed epidural adhesions at T8–T9 with nerve root distortion and no dye signal noted below T9, and a bone fragment extending into the thecal sac at T10. Left T8–T9 transforaminal epidural injection showed omnipaque highlight of the T8 and, minimally, the T9 nerve roots, and reproduced the patient's pain. The T8–T9 level was injected with 1 mL of 1% lidocaine and 1 mL of 80 mg/mL Depo Medrol. The T9–T10 level could not be injected foraminally or translaminarly because of bony fusion. Injection at the T10–T11 foramen showed restriction to flow and did not reproduce the patient's symptoms. The patient's left chest wall pain was relieved for 2 hours.

Case 4

A previously healthy 37-year-old man sustained a T4 burst fracture in a motorcycle crash and was treated nonoperatively. The ASIA grade of impairment was T4 Grade A. He presented with lower back pain radiating to the right leg and heel and associated with increased spasticity. MRI revealed bilateral L4–L5 facet hypertrophy and disk degeneration with disk space narrowing at L5–S1 with a small central disk bulge. Right L5–S1 transforaminal epidural injection did not help. Bilateral L4–L5 facet blocks with 0.5 mL of 40 mg/mL Depo Medrol and 1 mL of 0.5% bupivacaine resulted in an 80% pain improvement for at least 7 weeks.

Case 5

A healthy 34-year-old man sustained a C6 burst fracture during a motor vehicle crash, requiring an anterior C5 to C7 fusion and decompression. The ASIA grade of impairment was C7 Grade A. He presented with a 3-year history of chronic right shoulder pain refractory to physical therapy and trigger point injections. Cervical MRI revealed mild degenerative changes at C3–C4 and C4–C5 with right paracentral disk bulges causing mild neuroforaminal stenosis at both levels. Transforaminal injection at C4–C5 with 1 mL of 80 mg/mL Depo Medrol and 1 mL of 1% lidocaine resulted in resolution of his shoulder pain.

DISCUSSION

Pain is an ongoing management issue in individuals with SCI. The incidence of chronic pain in this population varies with the study cited, but a fair working prevalence is that 1 in 3 SCI patients experience severe chronic pain (1,2). However, in a postal survey, up to 80% of SCI patients reported pain, with upper extremity (69%) and back (61%) being the most common locations (3). This pain can affect mood (2–4), function (2), and quality of life (5,6). Despite this impact, patients with SCI are typically not satisfied with treatments directed to manage their pain (7). Effective interventions to diminish pain would, therefore, greatly impact the lives of patients with SCI.

Interventional spine therapy has become a mainstay in the management of spine and radicular pain (8,9). Temporary and sustaining relief can be achieved and can prevent the need for surgical treatment. A greater than 50% improvement in pain for at least 1 year is achieved in 75% of patients with fluoroscopically guided epidural steroid injections, whether radicular pain is from a herniated disk (9,10) or lumbar stenosis (11). Additionally, this type of intervention, if done selectively, provides diagnostic evaluation of a pain generator, providing confirmatory evidence that is beneficial when relying on diagnostic tools with high sensitivity but low specificity (ie, MRI scans). A number of spine pain generators can be evaluated in this manner, including the nerve root, annulus, disk, facet joint, and muscle. The site of injection and the level chosen further improves specificity in this assessment (12).

The management of pain disorders in the SCI population, as in all patients, depends on identification of the pain generator. To assist in this process, pain in the SCI population was differentiated by Siddal (13) based on pain location. In many patients, the location and type of pain allows the differential diagnosis and possible treatments to be narrowed. Pain is identified as above the level of injury, at the level of injury, or below the level of injury.

Pain above the level of injury can be somatic, sympathetic, or neuropathic. This pain can be related to the cause of SCI or can be unrelated. The stress force that occurs at a level of the vertebral column to cause a SCI is dissipated at the time of vertebral column failure (by fracture, dislocation, or both). Until that time, these forces act throughout that region of the spinal column, with at least the theoretical risk of early degenerative changes or instability at these locations (14). Additionally, the level or levels of fusion will increase the daily stresses on adjacent levels. More rapid degenerative disk or spine disease can occur by these two phenomena, with a subsequent risk of somatic and/or neuropathic pain (15). Case 5 is an example of neuropathic pain of this nature. It is important to rule out a syrinx or myelopathy caused by stenosis in these cases (16).

Pain at the level of injury is typically neuropathic or sympathetic. It can be caused by nerve root damage at the time of injury, incomplete spinal cord damage at the time of injury, syrinx, epidural fibrosis, or arachnoiditis. MRI with gadolinium enhancement or CT myelogram can clarify these possibilities. Confirmation can be obtained with selective transforaminal epidural steroid injection with epidurogram. Lysis of adhesions can be attempted to treat fibrosis. Chronic neuropathic pain without fibrosis can be transiently helped with epidural injection and then may be treated with antiseizure medication or a dorsal column stimulator. In such cases, if the nerve root involved is in the thoracic spine, consideration for dorsal root entry zone lesion can be given.

Pain below the level of injury can be somatic, sympathetic, or neuropathic. Spasticity or autonomic dysreflexia may accompany the pain. Somatic pain is seen in patients with incomplete injury although, as in Case 4, vague symptoms may be seen in otherwise complete SCI patients. Neuropathic pain can be caused by injury-related phenomenon such as syrinx, tethered cord, or arachnoiditis. It can also be caused by an unrelated spine phenomenon, such as disk herniation, degenerative disk disease, degenerative spine disease, or spinal stenosis.

In the cases cited, the pain generator was effectively found in the cervical spine in 1 case, in the thoracic spine in 2 cases, and in the lumbar spine in the other 2 cases. For 4 of the 5 cases, the success of the injection was sustained for long enough that the injection served as an adequate treatment modality. In the fourth case, Case 3, the injection was not an effective treatment, but suggested other treatment modalities (not undertaken because of additional medical complications). In 3 cases, epidural injection identified radicular pain as the cause for the pain complaint. In the fourth case, facet-mediated pain resulted in pain and an increase in spasticity, both of which were effectively treated by the block. The fifth case is an example of shoulder pain that was treated as musculoskeletal pain for years, although the final diagnosis was neuropathic pain caused by cervical degenerative disk disease, treated effectively with transforaminal epidural injection.

A curiosity we noted in cases 1 and 4 is the phenomenon of patients with motor and sensory complete, ASIA Grade A, neurological examinations with pain below the level of their injury. Additionally, these 2 patients experienced pain relief with interventional spine therapy. One cannot ignore the possible influence of placebo effect, although, in both cases, certain fluoroscopically confirmed injections were not helpful whereas others were effective. Theoretical considerations could include influence of sympathetic mediators of pain where afferents could extend cephalad around the spinal cord. This would be difficult to see in Case 4, where the level of injury is T4. However, it would be possible in Case 1, where the patient has a zone of incompletion through L3 and where the sympathetic afferents typically enter the spinal canal at L2. Alternatively, it is possible that a patient may be ASIA Grade A by the strict classification, but may have some incomplete spinal cord signaling through afferent or interneuron pathways, which might make vague pain sensation possible. Further evaluation of these possibilities will require a larger treatment group.

CONCLUSION

Interventional spine therapy has a role in the management of spine pain or radicular pain in patients with SCI. Other possible uses would include the treatment of spine triggers of spasticity or autonomic dysreflexia in patients with degenerative spine and degenerative disk disease. Further research into these uses in individuals with SCI is indicated, given these examples and the known power and low complications of these tools in the able-bodied population.

REFERENCES

- Siddall PJ, Loeser JD. Pain following spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2001;39:63–73. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravenscroft A, Ahmed YS, Burnside IG. Chronic pain after SCI. A patient survey. Spinal Cord. 2000;38:611–614. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns DM, Atkins RH, Scott MD. Pain and depression in acute traumatic spinal cord injury: origins of chronic problematic pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1996;77:329–335. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(96)90079-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summers JD, Rapoff MA, Varghese G, Porter K, Palmer RE. Psychosocial factors in chronic spinal cord injury pain. Pain. 1991;47:183–189. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(91)90203-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JA, Cardenas DD, Warms CA, McClellan CB. Chronic pain associated with spinal cord injuries: a community survey. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82:501–509. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2001.21855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stormer S, Gerner HJ, Gruninger W, et al. Chronic pain/dysaesthesiae in spinal cord injury patients: results of a multicentre study. Spinal Cord. 1997;35:446–455. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3100411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy D, Reid DB. Pain treatment satisfaction in spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2001;39:44–46. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huston CW, Slipman CW. Diagnostic selective nerve root blocks: indications and usefulness. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2002;13:545–565. doi: 10.1016/s1047-9651(02)00011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vad VB, Bhat AL, Lutz GE, Cammisa F. Transforaminal epidural steroid injections in lumbosacral radiculopathy: a prospective randomized trial. Spine. 2002;27:11–66. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200201010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JC, Lin E, Brodke DS, Youssef JA. Epidural injections for the treatment of symptomatic lumbar herniated discs. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2003;15:269–272. doi: 10.1097/00024720-200208000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botwin KP, Gruber RD, Bouchlas CG, et al. Fluoroscopically guided lumbar transformational epidural steroid injections in degenerative lumbar stenosis: an outcome study. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;81:898–905. doi: 10.1097/00002060-200212000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slipman CW, Chow DW. Therapeutic spinal corticosteroid injections for the management of radiculopathies. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2002;13:697–711. doi: 10.1016/s1047-9651(02)00004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddal P, Taylor D, Cousins M. Classification of pain after spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 1997;35:69–75. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3100365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Standert C, Cardenas DD, Anderson P. Charcot spine as a late complication of traumatic spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1997;78:221–225. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(97)90267-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima A, Nakajima A, Koyama K. Cervical spondylosis in paraplegic patients and analysis of the wheelchair driving action. Spinal Cord. 1997;35:768–772. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3100551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryce TN, Ragnarsson KT. Pain after spinal cord injury. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2000;11:157–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]