Abstract

Inflammatory cell activation by chemokines requires intracellular signaling through phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3-kinase) and the PI3-kinase-dependent protein serine/threonine kinase Akt. Atherosclerosis is a chronic inflammatory process driven by oxidatively modified (atherogenic) lipoproteins, chemokines, and other agonists that activate PI3-kinase. Here we show that macrophage PI3-kinase/Akt is activated by oxidized low-density lipoprotein, inflammatory chemokines, and angiotensin II. This activation is markedly reduced or absent in macrophages lacking p110γ, the catalytic subunit of class Ib PI3-kinase. We further demonstrate activation of macrophage/foam cell PI3-kinase/Akt in atherosclerotic plaques from apolipoprotein E (apoE)-null mice, which manifest an aggressive form of atherosclerosis, whereas activation of PI3-kinase/Akt was undetectable in lesions from apoE-null mice lacking p110γ despite the presence of class Ia PI3-kinase. Moreover, plaques were significantly smaller in apoE−/−p110γ−/− mice than in apoE−/−p110γ+/+ or apoE−/−p110γ+/−mice at all ages studied. In marked contrast to the embryonic lethality seen in mice lacking class Ia PI3-kinase, germ-line deletion of p110γ results in mice that exhibit normal viability, longevity, and fertility, with relatively well tolerated defects in innate immune and inflammatory responses that may play a role in diseases such as atherosclerosis and multiple sclerosis. Our results not only shed mechanistic light on inflammatory signaling during atherogenesis, but further identify p110γ as a possible target for pharmacological intervention in the primary and secondary prevention of human atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

Keywords: Akt, inflammation, macrophage, lipoproteins, G protein-coupled receptors

Akt regulates downstream signaling and effector molecules in the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3-kinase) pathway and is activated by phosphatidylinositol (3, 4, 5)-trisphosphate (PIP3)-dependent phosphorylation and localization. The catalytic subunits (p110α, p110β, and p110δ) of class Ia PI3-kinase produce PIP3 in response to growth factors, insulin, and other receptor tyrosine kinase agonists. p110γ, the catalytic subunit of class Ib PI3-kinase, produces PIP3 in response to chemokines and other G protein-coupled receptor agonists (1). Germ-line deletion of p110α or p110β results in embryonic lethality, suggesting a fundamental role in the development of class Ia PI3-kinase (2–5). In contrast, germ-line deletion of p110γ results in mice that display normal viability, longevity, and fertility (6–8). p110α and p110β are ubiquitous, whereas p110γ is expressed primarily in hematopoietic cells, muscle, and the pancreas. p110γ-deficient mice display defects in responses of immune and inflammatory cells to agonists of heterotrimeric G protein-coupled receptors (6–8). Mice lacking p110γ display impaired neutrophil chemotaxis and respiratory burst in response to fMLP and C5a, as well as reduced thymocyte survival and activation of mature T lymphocytes (6–8). PIP3 production and activation of Akt are markedly reduced in p110γ−/− neutrophils compared with wild-type neutrophils (8). p110γ−/− peritoneal macrophages display reduced migration toward many chemotactic factors, as well as diminished accumulation in a septic peritonitis model (8). These studies in p110γ−/− mice demonstrate the critical role of p110γ in the activation of cells that participate in a wide range of inflammatory processes.

Numerous studies have established the importance of PI3-kinase in responses of macrophages, vascular smooth muscle cells, and T lymphocytes to atherogenic mediators. Oxidatively modified low-density lipoprotein (LDL), one of the most potent of such mediators, exerts multiple effects on these cell types, including induction of protein tyrosine phosphorylation and PI3-kinase activation (9). Oxidized LDL is a survival factor for bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) in culture, inhibiting apoptosis after withdrawal of macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF), whereas native and acetylated LDL have no effect on apoptosis (10). Two specific, structurally unrelated inhibitors of PI3-kinase, LY294002 and wortmannin, block the survival-promoting effect of oxidized LDL as well as phosphorylation of Akt, a major PI3-kinase-dependent antiapoptotic mediator. In addition to having a direct effect on macrophage survival, oxidized LDL plays a priming role in macrophage proliferation in atherosclerotic lesions by triggering the release of granulocyte/M-CSF (GM-CSF) via activation of PI3-kinase and protein kinase C (PKC) (11–13). GM-CSF release from macrophages in response to oxidized LDL induces proliferation in an autocrine or a paracrine fashion, suggesting that both the antiapoptotic and proliferative effects are PI3-kinase-dependent. Because inflammatory cell migration, proliferation, and activation require signaling through PI3-kinase, we hypothesized that, to the extent that it is driven by these processes, atherogenesis should be attenuated by blocking p110γ, a major PI3-kinase isoform in inflammatory cells.

Results

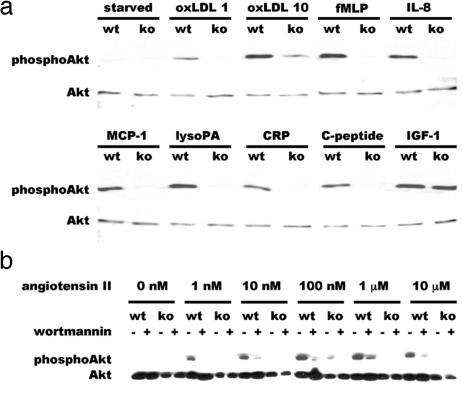

The ability of oxidized LDL and atherogenic cytokines/chemokines to trigger PI3-kinase signaling and Akt activation in inflammatory cells is well established (11, 12, 14). To determine whether p110γ is the specific isoform of PI3-kinase involved in this pathway, we exposed BMDMs to these G protein-coupled receptor agonists and immunoblotted lysates with a phosphospecific antibody that recognizes activated Akt. Akt phosphorylation in response to oxidized LDL, fMLP, IL-8, MCP-1, and lysophosphatidic acid was strongly induced in wild-type macrophages, but absent or barely detectable in p110γ−/− macrophages (Fig. 1a). C-reactive protein, an acute-phase reactant that rises in inflammatory conditions, and C-peptide, a cleavage product of proinsulin that is elevated in type 2 diabetes mellitus, have been implicated recently as proatherogenic agents (15–18) that can activate PI3-kinase (15, 18–20). Both C-reactive protein (10 μg/ml) and C-peptide (1 nM) induced PI3-kinase/Akt activation in wild-type but not in p110γ−/− macrophages (Fig. 1a). Angiotensin II, which elicits numerous responses in the cardiovascular system, some of which are deleterious when the renin-angiotensin system is chronically hyperactivated, induced phosphorylation of Akt in a dose-dependent manner in p110γ+/+ but not in p110γ−/− BMDMs (Fig. 1b). In contrast, both p110γ−/− and wild-type BMDMs showed similar Akt activation in response to IGF-1 (Fig. 1a), demonstrating that class Ia PI3-kinase is present and capable of activating Akt in p110γ-null BMDMs. Wortmannin, an inhibitor of all class I PI3-kinases, blocked Akt phosphorylation in response to all agonists tested in both wild-type and p110γ−/− BMDMs (Fig. 1b and data not shown). The presence or absence of apoE had no effect on PI3-kinase activation because Akt phosphorylation in response to all agonists used was similar in apoE−/− and apoE+/+ BMDMs (data not shown). In addition, Akt activation in p110γ+/+ and p110γ+/− macrophages in response to all agonists tested was identical (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Western blot analysis of macrophage lysates from p110γ+/+ and p110γ−/− mice. (a) Lysates of BMDMs exposed (15 min at 37°C) to various agonists after 24 h of serum deprivation were separated by SDS/PAGE and immunoblotted with phosphospecific Akt (Ser473) antibody (Upper). Separate but identical blots were probed with nonphosphospecific Akt antibody to demonstrate equal loading of lanes (Lower). Agonist concentrations were oxidized LDL, 1 and 10 μg/ml; fMLP, 10 μM; IL-8, 10 ng/ml; MCP-1, 20 ng/ml; lysophosphatidic acid, 10 μM; C-reactive protein, 10 μg/ml; C-peptide, 1 nM; IGF-1, 20 nM. (b) Cultured BMDMs were exposed to angiotensin II at the concentrations indicated, for 5 min at 37°C before cell lysis, in the presence (20 nM) or absence of wortmannin. wt, wild type; ko, p110γ−/−.

Deletion of the apoE gene in mice causes marked elevation of proatherogenic lipoproteins and marked reduction of antiatherogenic high-density lipoprotein (HDL), resulting in an aggressive form of atherosclerosis (21). We performed an analysis of atherosclerotic lesions in animals fed a standard laboratory chow diet rather than in those fed a “Western”-type diet (rich in cholesterol and saturated fat) because feeding apoE−/− mice a Western diet is known to accelerate and exacerbate an atherosclerotic process that is already highly exuberant in apoE−/− animals fed a standard chow diet. Hence, we felt that biologically important differences in atherogenesis between apoE−/−p110γ+/+ and apoE−/−p110γ−/− mice would tend to be obscured if the animals were fed a Western diet.

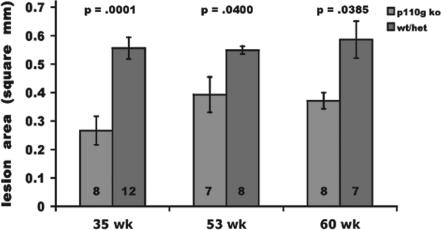

To determine the contribution of p110γ to atherosclerotic plaque progression, we cross-bred p110γ−/− and apoE−/− mice. At 36 and 55 weeks, plasma total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, non-HDL cholesterol, and triglycerides were similar among apoE−/−p110γ+/+, apoE−/−p110γ+/−, and apoE−/−p110γ−/− mice, although after 60 weeks there was a modest but statistically significant reduction of plasma total and non-HDL cholesterol in apoE−/−p110γ−/− mice [supporting information (SI) Table 1]. Most notably, atherosclerotic lesions were smaller in apoE−/−p110γ−/− mice than in age-matched apoE−/−p110γ+/+ or apoE−/−p110γ+/− littermates at all time points. In apoE−/−p110γ−/− mice, aortic root lesion size was reduced by 52% (P = 0.0001), 32% (P = 0.0400), and 36% (P = 0.0385) at 35, 53, and 60 weeks of age, respectively (Fig. 2). Reduction of lesion size, although statistically significant in older mice (53 and 60 weeks), was less than in younger mice (35 weeks) due to progression of atherosclerosis in the double knockout mice. Our hypothesis was that reduced reactivity of inflammatory cells deficient in p110γ in response to atherogenic agonists and chemokines should result in attenuation of atherosclerosis in apoE knockout mice. p110γ+/+ and p110γ+/− macrophages displayed similar Akt activation in response to these agonists/chemokines when tested in vitro. Furthermore, immunohistochemical analysis of PI3-kinase/Akt activation in aortic root lesions from apoE−/−p110γ+/+ and apoE−/−p110γ+/− mice yielded similar results (Figs. 3 and 4). Therefore, in quantify-ing aortic root atherosclerosis, we pooled results from apoE−/−p110γ+/+ and apoE−/−p110γ+/− mice. The mice included in the quantitative analysis of aortic root atherosclerosis (Fig. 2) were all females. Qualitatively similar results were obtained when male animals were analyzed (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Aortic root atherosclerosis was quantified on anti-Mac-3-stained cryosections by digital histomorphometry using ImagePro Plus software. Atherosclerosis in apoE−/−p110γ+/+ or apoE−/−p110γ+/− mice was compared with that in apoE−/−p110γ−/− mice. At 35 weeks (n = 8 for apoE−/−p110γ+/+ or apoE−/−p110γ+/− mice; n = 12 for apoE−/−p110γ−/− mice), double knockout mice displayed 52% reduction of lesion area (P = 0.0001). At 53 weeks (n = 8 for apoE−/−p110γ+/− mice; n = 7 for apoE−/−p110γ−/− mice), double knockout mice displayed 32% reduction of lesion area (P = 0.04). At 60 weeks (n = 7 for apoE−/−p110γ+/+ or apoE−/−p110γ+/− mice; n = 8 for apoE−/−p110γ−/− mice), double knockout mice displayed 36% reduction of lesion area (P = 0.0385). Error bars represent the SE of the mean.

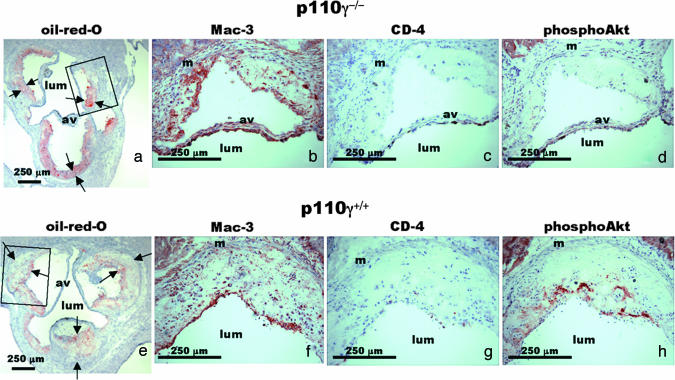

Fig. 3.

Lipid content, cellular composition, and Akt activation were examined in atherosclerotic lesions. Aortic root cryosections from a 53-week-old female apoE−/−p110γ−/− mouse (a–d) and a female apoE−/−p110γ+/+ littermate (e–h) stained with oil-red-O to visualize lipids (a and e), anti-Mac-3 to visualize macrophages (b and f), anti-CD4 to visualize T lymphocytes (c and g), and phosphoSer473 Akt antibody to detect Akt activation (d and h). Boxes in a and e indicate areas of higher magnification than in b–d and f–h, respectively. Arrows indicate position of endothelial and medial boundaries of lesions. Av, aortic valve leaflet; lum, lumen of aorta.

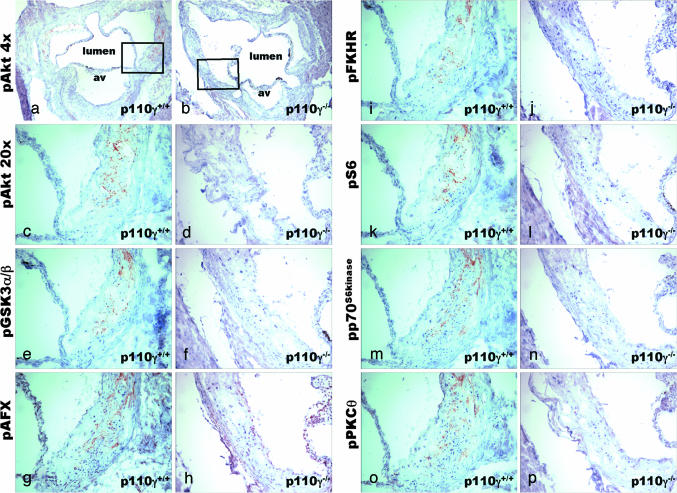

Fig. 4.

The activation state of downstream effector and signaling molecules in the PI3-kinase/Akt pathway was assayed by immunohistochemistry. Immunohistochemistry of adjacent aortic root cryosections from 36-week-old apoE−/−p110γ+/+ (a, c, e, g, i, k, m, o) and apoE−/−p110γ−/− (b, d, f, h, j, l, n, p) mice. Sections were stained with phosphospecific antibodies against Akt (Magnification: a and b, ×4), Akt (Magnification: c and d, ×20), GSK3α/β (e and f), AFX (g and h), FKHR (i and j), S6 ribosomal protein (k and l), p70S6kinase (m and n), and PKCθ (o and p). av, aortic valve leaflet.

Atherosclerotic plaques in the aortic root of 35-, 53-, and 60-week-old apoE−/−p110γ+/+ and apoE−/−p110γ+/− mice that consumed a standard chow diet were complex and extensive, occupying most of the sinuses of Valsalva (Fig. 3). In age-matched apoE−/−p110γ−/− mice, the lesions were significantly smaller. Numerically, macrophage/foam cells were the predominant cell type within lesions of both apoE−/−p110γ+/+ and apoE−/−p110γ−/− mice, with a relative paucity of helper T lymphocytes, as determined by staining with Mac-3 and CD4, respectively (Fig. 3 b, c, f, and g). The fully developed lesions in apoE−/−p110γ+/+ and apoE−/−p110γ+/− mice ages 35 weeks and older stained strongly with the phosphospecific Akt antibody (Fig. 3h). In striking contrast, the aortic root lesions of age-matched apoE−/−p110γ−/− mice showed no detectable Akt phosphorylation (Fig. 3d). These immunohistochemical findings correlate precisely with the results of immunoblotting by using the same phosphospecific Akt antibody on lysates of cultured macrophages stimulated with oxidized LDL or atherogenic cytokines/chemokines (Fig. 1). In the aortic root atherosclerotic lesions, phosphoAkt staining localized primarily in macrophage-rich areas of the lesions (SI Fig. 5), and dual immunohistochemical staining (SI Fig. 6) with anti-phosphoAkt and anti-Mac-3 demonstrated that the subpopulation of macrophage/foam cells residing in the areas of highest cell density display activated PI3-kinase/Akt. Compared with the number of macrophages found in aortic root lesions, very few smooth muscle cells were present in lesions stained with antismooth muscle cell α-actin from either apoE−/−p110γ+/+ or apoE−/−p110γ−/− mice (data not shown).

Numerous signaling and effector proteins are regulated by PI3-kinase/Akt-dependent serine/threonine phosphorylation. These include glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3), PKC, p70S6kinase, and FKHR (a member of the FOXO family of transcription factors), which regulate cellular energy metabolism, protein translation, and gene expression. Staining with phosphospecific antibodies against GSK3α/β, PKCθ, p70S6kinase, FKHR, AFX-1 (another member of the FOXO family of transcription factors), and S6 ribosomal protein was seen in aortic root atherosclerotic lesions from apoE−/−p110γ+/+, and also in apoE−/−p110γ+/− mice (data not shown), but not in lesions from apoE−/−p110γ−/− mice (Fig. 4), demonstrating that not only are formation of D3-phosphorylated phosphoinositides and Akt activation absent or markedly reduced in plaque macrophages when p110γ is absent, but also that PI3-kinase/Akt-dependent phosphorylation of downstream molecules in this pathway is abolished.

The FOXO family transcription factor FKHR is regulated by PI3-kinase/Akt (22). FKHR and other members of the FOXO family are phosphorylated by Akt when PI3-kinase is activated, resulting in their exclusion from the nucleus (22). We used phosphospecific and nonphosphospecific antibodies against FKHR to determine simultaneously the localization (nuclear vs. cytoplasmic) and phosphorylation state of FKHR in atherosclerotic plaque macrophage/foam cells. FKHR was phosphorylated and localized in the cytosol in plaque macrophages from apoE−/−p110γ+/+ mice (SI Fig. 7 a and b), whereas it was unphosphorylated and localized in the nucleus in plaque macrophages from apoE−/−p110γ−/− mice (SI Fig. 7 c and d), corroborating the absence of PI3-kinase/Akt activation in foam cell/macrophages of p110γ-deficient mice.

Discussion

Atherosclerosis and its sequelae, including myocardial infarction and stroke, are the leading causes of mortality and morbidity in the developed world (23–25). Here we have demonstrated that p110γ is required for activation of Akt in macrophages in response to oxidized LDL, atherogenic cytokines, and angiotensin II in vitro, as well as in atherosclerotic lesions of hypercholesterolemic mice in vivo. Moreover, we have shown that abrogation of Akt activation in macrophage/foam cells by germ-line deletion of the p110γ gene correlates with the persistent reduction of plaque size. Double-mutant mice had smaller lesions with fewer Mac-3-positive cells (macrophages and macrophage-derived foam cells), but the overall density of macrophage/foam cells was similar in lesions from apoE−/−p110γ+/+ and apoE−/−p110γ−/− mice (data not shown). However, as shown in SI Figs. 5 and 6, the density of macrophage/foam cells varied considerably within lesions, and PI3-kinase/Akt activation only occurred in areas of high cell density, suggesting that autocrine or paracrine stimulation of macrophage/foam cell activation and proliferation contributes to atherogenesis, a notion that is well supported in the literature (see refs. 11 and 12). These findings are consistent with a model of macrophage proliferation within atherosclerotic plaques proposed by Biwa et al. (11, 12), wherein the initial effect of oxidized LDL may be to trigger (PKC- and p110γ-dependent) synthesis and release of GM-CSF by resident macrophage/foam cells. Locally released GM-CSF then stimulates (class Ia PI3-kinase-dependent) proliferation of adjacent macrophages in an autocrine/paracrine manner. We studied the effect of p110γ deficiency on macrophage expression of GM-CSF both in macrophage culture and in situ in frozen sections of lesions. We chose to focus on GM-CSF because this cytokine has been shown not only to be expressed by macrophages in response to atherogenic mediators such as oxidized LDL, but also to be at least partially dependent on PI3-kinase activity in macrophages. Furthermore, it has been hypothesized that macrophage-derived GM-CSF plays an important role in driving plaque progression through an autocrine or paracrine mechanism (see refs. 11 and 12). However, in our hands, the levels of GM-CSF in culture medium (both at baseline and after stimulation with oxidized LDL and other proatherogenic cytokines and chemokines) and in frozen sections of actual lesions was below the level of detection by RIA and in situ hybridization.

The modest reduction of total and non-HDL cholesterol in apoE−/−p110γ−/− compared with apoE−/−p110γ+/+ mice at the very late time point of 60 weeks is intriguing but unlikely to have played a major role in the attenuation of plaque size in p110γ−/− mice because the greatest difference in plaque size occurred at 35 weeks, when cholesterol levels were similar. That cholesterol bound to atherogenic (non-HDL) lipoproteins as well as total cholesterol was reduced in apoE−/−p110γ−/− mice at 60 weeks of age implies a (late-appearing) reduction of cholesterol absorption or biosynthesis as result of p110γ deficiency rather than increased elimination. It is unlikely that increased reverse cholesterol transport was responsible for reduced atherogenesis in apoE−/−p110γ−/− mice because an increased level of HDL cholesterol in apoE−/−p110γ−/− mice would be expected if this were the case.

The complete absence of immunohistochemically detectable Akt activation and of PI3-kinase-dependent phosphorylation of downstream effector molecules in cells of atherosclerotic lesions from apoE−/−p110γ−/− mice was unexpected because p110γ is only one of several agonist-activated (class I) isoforms of PI3-kinase found in inflammatory cells. Deletion of the p110γ gene alone was sufficient to abrogate all detectable PI3-kinase/Akt activation as well as PI3-kinase-dependent phosphorylation of downstream effector molecules FKHR, AFX, GSK3, p70S6kinase, S6 ribosomal protein, and PKCθ within the context of atherosclerotic lesions in apoE−/− mice. This remarkable phenomenon was associated with a significant reduction of atherosclerotic lesion size. In the present study, we demonstrated an absolute requirement for p110γ in Akt activation in cultured BMDMs in response to many of the agonists, chemokines, and inflammatory mediators commonly implicated in atherogenesis. This finding lends strong support for the critical role of p110γ in atherosclerosis progression and may in part explain the absence of Akt activation in lesions from apoE−/−p110γ−/− mice.

Oxidative stress in general, and oxidatively modified lipoproteins in particular, play a major role in driving atherosclerotic plaque progression. Here we have demonstrated that oxidized LDL is a potent macrophage agonist, inducing PI3-kinase/Akt activation, and that this activation requires p110γ. Because activation of inflammatory cells results in stimulation of respiratory burst and generation of oxygen-derived free radicals, the interaction of oxidatively modified lipoproteins with plaque macrophages can be expected to result in cellular activation, generation of oxygen-derived free radicals, increased formation of oxidatively modified lipoproteins, and so on in a self-reinforcing process of feed-forward stimulation. Because p110γ-deficient inflammatory cells are severely impaired in their ability to generate superoxide in response to chemokines and other agonists (6–8), it is likely that deficiency (or inhibition) of p110γ in vivo would abrogate this process, reducing oxidative stress within the atherosclerotic plaque, reducing lesion size, and possibly increasing plaque stability.

Although plaque rupture occurs only sporadically in the commonly studied mouse models of atherosclerosis, including in the apoE-deficient mice used in the present study, the possibility that inhibition of PI3-kinase in atherosclerotic lesions might affect plaque stability (in addition to retarding plaque progression) is clinically relevant. Inherent in the unstable plaque is a higher propensity to rupture, thereby causing acute thrombotic occlusion of arteries that leads to clinical syndromes such as myocardial infarction and stroke (26). Oxidative stress within atherosclerotic lesions, a potential contributor to plaque destabilization (27–29), should decline in the absence of p110γ, given the markedly reduced respiratory burst seen in p110γ-null inflammatory cells (6–8). Here we have demonstrated that angiotensin II signaling, which contributes to oxidative stress, plaque progression, and plaque destabilization (30, 31), is markedly attenuated in p110γ-null macrophages.

Until recently, exploitation of PI3-kinase as a target for preventative or therapeutic intervention in the numerous disease processes in which it has been implicated has been hampered by the lack of isoform-specificity of the available inhibitors such as wortmannin and LY294002. In marked contrast to these nonspecific but widely used inhibitors, AS605240, a recently described thiazolidinedione derivative that is an ATP-competitive inhibitor of p110γ with a ki of 0.0078 μM, displays 30-fold higher potency against p110γ in vitro compared with the other PI3-kinases. AS605240 has been shown to block glomerulonephritis in a mouse model of systemic lupus erythematosus as well as joint inflammation in a mouse model of rheumatoid arthritis (32, 33). It would be of interest to test this, or related compounds, for potential antiatherogenic activity in LDL receptor- or apoE knockout mice.

In summary, the present study shows that p110γ is required for Akt activation in macrophages in response to oxidized LDL, atherogenic chemokines, and angiotensin II in vitro and in atherosclerotic lesions of hypercholesterolemic mice in vivo, and that loss of p110γ results in reduced lesion size. Moreover, it provides evidence to support the possibility that inhibition of p110γ could also stabilize atherosclerotic plaques. Mice lacking p110γ or expressing in its place a catalytically inactive mutant display normal viability, fertility, and longevity despite the presence of specific defects in inflammatory and immune cell development and activation (6–8, 34). In light of the well tolerated nature of these defects, p110γ is a potential target for a drug that could be distributed systemically yet maintain a high therapeutic index. Pharmacologic suppression of inflammatory and immune responses is a cornerstone for the treatment of a wide variety of conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, Crohn's disease, and organ transplant rejection. Our findings provide a compelling rationale for extending such an approach to the prevention and treatment of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

Methods

Mice.

Mice were handled in accordance with guidelines of the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. ApoE−/− mice (C57BL/6J) were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). p110γ−/− mice (C57BL/6J) were generated as described previously (7). Both lines of mice had previously been backcrossed onto a C57BL/6 background for >12 generations. Mice consuming standard laboratory chow (Harlan Teklad F6 Rodent Diet) containing 6% crude fat were killed at various time points from 22 to 60 weeks of age. Aortas were removed en bloc, and cryosections of the aortic root were obtained at the level of the aortic valve and sinuses of Valsalva. The cryosections were stained for lipid content with oil-red-O and for immunoperoxidase with antibodies against macrophages (Mac-3), smooth muscle cells (α-actin), and T lymphocytes (CD4), as well as for Akt phosphoSer473.

Measurement of Cholesterol and Triglycerides.

Serum was separated from erythrocytes by centrifugation at 1,100 × g at 4°C and assayed for total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and triglycerides on a Hitachi 911 automated analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) by using enzymatic methods (35). The assays are standardized through the Lipid Standardization Program of the Centers for Disease Control (Atlanta, GA). Non-HDL cholesterol was computed as the difference between total and HDL cholesterol.

Lipoprotein Purification and Oxidation.

LDL, HDL, very LDL, and very HDL were isolated by preparative ultracentrifugation from human blood plasma according to the method of Hatch (36) and used within 2 weeks of purification. Oxidation of LDL was performed by incubation of LDL in PBS at a concentration of 5 mg/ml (total protein) with 5 μM CuSO4 at 37°C for 24 h. Native and oxidized LDL were preserved with 1 mM EDTA and 0.01% sodium azide and stored at 0°C in tightly sealed tubes under nitrogen gas to minimize further oxidation.

Analysis of BMDMs.

Femurs from 1-month-old mice were harvested after pheonobarbital-induced killing. Marrow was flushed out with DMEM and cultured in DMEM containing 10% FBS and 20% L cell-conditioned medium, which supports monocyte/macrophage proliferation as a result of M-CSF secreted by L cells. Cells were incubated overnight in bacterial Petri dishes, and nonadherent cells were collected and passaged for further culture. Adherent cells were replated the next day at a density of 5 × 105 cells per well in 60-mm tissue culture plates. After overnight serum starvation, cells were exposed to agonists with or without pretreatment (20 min) in 20 nM wortmannin.

Western Blot Analysis of PI3-Kinase Activation.

The primary antibody, rabbit polyclonal anti-phosphoAkt (Ser473) (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), detects Akt only when Akt is phosphorylated on serine in position 473. Phosphorylation of this residue is wortmannin-sensitive and PI3-kinase-dependent. Total Akt was detected with a rabbit polyclonal Akt (Cell Signaling Technology) that recognizes all phosphorylation states of Akt.

Analysis and Quantification of Aortic Atherosclerosis.

Double knockout and littermate control mice were killed at various time points to quantify early (nascent) and late (advanced) atherosclerotic lesions as described previously (37). Because our hypothesis was that reduced reactivity of inflammatory cells deficient in p110γ to atherogenic agonists and chemokines should result in attenuation of atherosclerosis in apoE knockout mice, and p110γ+/+ and p110γ+/− macrophages displayed similar Akt activation in response to these agonists/chemokines, we pooled results from apoE−/−p110γ+/+ and apoE−/−p110γ+/− mice. The mice included in a quantitative analysis of aortic root atherosclerosis were all females. Qualitatively similar results were obtained when male animals were analyzed. Similarly, immunohistochemical findings with phosphospecific antibody staining of aortic root lesions from apoE−/−p110γ+/+ and apoE−/−p110γ+/− mice were identical.

Immunohistochemistry.

Histopathological and immunohistochemical analysis was performed on serial cryostat sections (6 μm) counterstained with hematoxylin as described previously (38). Antibodies against phosphoAkt Ser473 (IHC-specific), Akt, FKHR, phosphoFKHR, phosphoAFX, phosphoGSK3α/β, phosphoPKCθ, phosphop70S6kinase, and phosphoS6 ribosomal protein were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology and used at a dilution of 1:100. Mac-3, CD4, and smooth muscle actin antibodies were obtained from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA) and used at dilutions of 1:1,000, 1:200, and 1:1,000, respectively.

Statistical Analysis.

Student's two-tailed t test was used to determine the statistical significance of differences in serum lipoprotein/triglyceride levels and aortic root atherosclerosis between apoE−/−p110γ+/+ or apoE−/−p110γ+/− mice and age-matched apoE−/−p110γ−/− mice.

Acknowledgments

We thank Bradley Smith and Glen J. Bubley for discussion of immunohistochemistry using phosphospecific antibodies, and Kenneth Swanson for assistance with BMDM isolation and culture. This work was supported by grants from the Donald W. Reynolds Foundation (to J.D.C., P.L., and S.J.F.) and National Institutes of Health Grant GM41890 (to L.C.C.).

Abbreviations

- PI3-kinase

phosphoinositide 3-kinase

- M-CSF

macrophage colony-stimulating factor

- GM-CSF

granulocyte/M-CSF

- BMDM

bone marrow-derived macrophage

- GSK3

glycogen synthase kinase 3.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0702663104/DC1.

References

- 1.Cantley LC. Science. 2002;296:1655–1657. doi: 10.1126/science.296.5573.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lelievre E, Bourbon PM, Duan LJ, Nussbaum RL, Fong GH. Blood. 2005;105:3935–3938. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-10-3955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bi L, Okabe I, Bernard DJ, Nussbaum RL. Mamm Genome. 2002;13:169–172. doi: 10.1007/BF02684023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bi L, Okabe I, Bernard DJ, Wynshaw-Boris A, Nussbaum RL. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:10963–10968. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.16.10963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brachmann SM, Ueki K, Engelman JA, Kahn RC, Cantley LC. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:1596–1607. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.5.1596-1607.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sasaki T, Irie-Sasaki J, Jones RG, Oliveira-dos-Santos AJ, Stanford WL, Bolon B, Wakeham A, Itie A, Bouchard D, Kozieradzki I, et al. Science. 2000;287:1040–1046. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5455.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Z, Jiang H, Xie W, Zhang Z, Smrcka AV, Wu D. Science. 2000;287:1046–1049. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5455.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hirsch E, Katanaev VL, Garlanda C, Azzolino O, Pirola L, Silengo L, Sozzani S, Mantovani A, Altruda F, Wymann MP. Science. 2000;287:1049–1053. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5455.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martens JS, Reiner NE, Herrera-Velit P, Steinbrecher UP. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:4915–4920. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.9.4915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hundal RS, Salh BS, Schrader JW, Gomez-Munoz A, Duronio V, Steinbrecher UP. J Lipid Res. 2001;42:1483–1491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Biwa T, Sakai M, Shichiri M, Horiuchi S. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2000;7:14–20. doi: 10.5551/jat1994.7.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Biwa T, Sakai M, Matsumura T, Kobori S, Kaneko K, Miyazaki A, Hakamata H, Horiuchi S, Shichiri M. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:5810–5816. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.8.5810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sakai M, Kobori S, Miyazaki A, Horiuchi S. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2000;11:503–509. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200010000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fruman DA, Cantley LC. Semin Immunol. 2002;14:7–18. doi: 10.1006/smim.2001.0337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marx N, Walcher D, Raichle C, Aleksic M, Bach H, Grub M, Hombach V, Libby P, Zieske A, Homma S, Strong J. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:540–545. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000116027.81513.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paul A, Ko KW, Li L, Yechoor V, McCrory MA, Szalai AJ, Chan L. Circulation. 2004;109:647–655. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000114526.50618.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ridker PM, Cannon CP, Morrow D, Rifai N, Rose LM, McCabe CH, Pfeffer MA, Braunwald E. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:20–28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walcher D, Aleksic M, Jerg V, Hombach V, Zieske A, Homma S, Strong J, Marx N. Diabetes. 2004;53:1664–1670. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.7.1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khreiss T, Jozsef L, Hossain S, Chan JS, Potempa LA, Filep JG. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:40775–40781. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205378200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chi M, Tridandapani S, Zhong W, Coggeshall KM, Mortensen RF. J Immunol. 2002;168:1413–1418. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.3.1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang SH, Reddick RL, Piedrahita JA, Maeda N. Science. 1992;258:468–471. doi: 10.1126/science.1411543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brunet A, Bonni A, Zigmond MJ, Lin MZ, Juo P, Hu LS, Anderson MJ, Arden KC, Blenis J, Greenberg ME. Cell. 1999;96:857–868. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80595-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glass CK, Witztum JL. Cell. 2001;104:503–516. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00238-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lusis AJ. Nature. 2000;407:233–241. doi: 10.1038/35025203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ross R. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:115–126. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901143400207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Libby P, Aikawa M. Nat Med. 2002;8:1257–1262. doi: 10.1038/nm1102-1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakata Y, Maeda N. Circulation. 2002;105:1485–1490. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000012142.69612.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rajagopalan S, Meng XP, Ramasamy S, Harrison DG, Galis ZS. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:2572–2579. doi: 10.1172/JCI119076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aikawa M, Sugiyama S, Hill CC, Voglic SJ, Rabkin E, Fukumoto Y, Schoen FJ, Witztum JL, Libby P. Circulation. 2002;106:1390–1396. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000028465.52694.9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wassmann S, Czech T, van Eickels M, Fleming I, Bohm M, Nickenig G. Circulation. 2004;110:3062–3067. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000137970.47771.AF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hernandez-Presa M, Bustos C, Ortego M, Tunon J, Renedo G, Ruiz-Ortega M, Egido J. Circulation. 1997;95:1532–1541. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.6.1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barber DF, Bartolome A, Hernandez C, Flores JM, Redondo C, Fernandez-Arias C, Camps M, Ruckle T, Schwarz MK, Rodriguez S, et al. Nat Med. 2005;11:933–935. doi: 10.1038/nm1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Camps M, Ruckle T, Ji H, Ardissone V, Rintelen F, Shaw J, Ferrandi C, Chabert C, Gillieron C, Francon B, et al. Nat Med. 2005;11:936–943. doi: 10.1038/nm1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patrucco E, Notte A, Barberis L, Selvetella G, Maffei A, Brancaccio M, Marengo S, Russo G, Azzolino O, Rybalkin SD, et al. Cell. 2004;118:375–387. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dorfman SE, Wang S, Vega-Lopez S, Jauhiainen M, Lichtenstein AH. J Nutr. 2005;135:492–498. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.3.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hatch FT. Adv Lipid Res. 1968;6:1–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sukhova GK, Wang B, Libby P, Pan JH, Zhang Y, Grubb A, Fang K, Chapman HA, Shi GP. Circ Res. 2005;96:368–375. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000155964.34150.F7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sukhova GK, Zhang Y, Pan JH, Wada Y, Yamamoto T, Naito M, Kodama T, Tsimikas S, Witztum JL, Lu ML, et al. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:897–906. doi: 10.1172/JCI14915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]