Abstract

The effect of pH modifying excipients on the chemical stability of a model peptide (VYPNGA) and the degradation of poly(DL-lactide-co-glycolide)(PLGA) was studied in PLGA films under accelerated storage conditions. pH modifiers included a basic amine (proton sponge), a basic salt (magnesium hydroxide) and two pH buffers (ammonium acetate and magnesium acetate). Changes in film pH were monitored using 13C NMR, peptide degradation products were quantified by LC/MS/MS and PLGA degradation was analyzed by TGA, DSC and SEC. Inclusion of pH modifiers had little impact on PLGA degradation. The proton sponge affected an initial decrease in pH but reduced peptide deamidation and chain cleavage relative to an unbuffered control. Magnesium hydroxide produced an initial increase in pH but also showed increased peptide deamidation. Ammonium acetate decreased pH and increased peptide chain cleavage, presumably due to increased PLGA hydrolysis. Magnesium acetate buffer increased the initial pH but resulted in increased peptide loss. The extent of peptide acylation increased in all formulations, most notably in the proton sponge modified films. The effectiveness of pH modifiers in PLGA formulations under storage conditions is dependant on both the mechanism of pH alteration and the peptide degradation reaction of interest.

Keywords: PLGA, peptide stability, pH modifiers, basic salts, proton sponge

1. Introduction

Poly(lactide-co-glycolide)(PLGA) has been used effectively for the controlled delivery of peptide and protein drugs and vaccines [1–4]. A limitation of these systems is the chemical instability of the peptide or protein in the matrix [5–7], which has been linked to a reduced microclimate pH resulting from PLGA biodegradation [6–9]. Many pH modifiers, mostly basic salts, have been included in PLGA formulations in an attempt to stabilize the pH, but these techniques may not prevent degradation reactions that are both acid and base labile, such as deamidation [2, 10–12]. Inclusion of salts to modify pH has also proved problematic due to their poor solubility in many of the organic solvents used to dissolve PLGA, resulting in a heterogeneous distribution within the matrix and localized acidic and basic microdomains [10]. The addition of basic salts has been linked to increased water uptake in PLGA matrices as well [10, 13], which may increase hydrolytic peptide and protein degradation reactions. Buffers and proton scavengers or “sponges” are possible alternatives to basic salts. Proton sponges are typically amines that are more basic than the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API), and so are preferentially protonated without altering the overall pH of the formulation [14]. Buffers also have the potential to neutralize the acidic monomers produced by PLGA degradation without producing a basic pH.

The studies reported here address the changes in chemical stability of a model hexapeptide (VYPNGA) and the chemical and physical properties of PLGA films containing various pH modifiers under accelerated storage conditions. VYPNGA was chosen for this study because it has limited secondary structure and its pH degradation profile has been established in solution and polymeric solids [15]. Chemical stability was chosen as the focus of this study because it is often a more sensitive measure of stability than peptide activity.

In a previous report, we demonstrated VYPNGA undergoes three types of chemical degradation when encapsulated in PLGA: deamidation, amide bond cleavage and acylation [16]. The products of these reactions were identified by LC/MS/MS and described in detail in the previous report [16]. In this study, several types of pH modifiers were investigated for their ability to either stabilize or destabilize a model peptide incorporated in PLGA films: a superbasic amine or proton sponge, a basic salt, a neutral buffer, and a slightly acidic buffer. The effect of each additive on the chemical stability of an incorporated peptide was studied by quantifying parent peptide loss and the production of known degradation products. Additionally, the effect of each additive on the PLGA matrix was studied by monitoring the protonation state of a ‘pH’ probe, the water content of the matrix, glass transition temperature (Tg) of the polymer/water mixture, and the polymer molecular weight (Mn) under accelerated storage conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Materials

Val-Tyr-Pro-Asn-Gly-Ala (VYPNGA) (Asn-hexapeptide) was synthesized by American Peptide Company, Inc. (Sunnyvale, CA). All amino acids, except Gly, were in the L-configuration. Peptide purity was determined by RP-HPLC to be > 95.0%. 50/50 Poly (DL-lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) and polystyrene narrow molecular weight standards (151.7, 66.35, 38.1, 19.88, 10.05, 4.92, 2.35 and 1.26 kDa) were purchased from Absorbable Polymers International (Pelham, AL). The inherent viscosity of PLGA was 0.58 dL/g and the molecular weight was 75.4 kDa. Universally labeled 13C fumaric acid was purchased from Cambridge Isotope (Andover, MA) and titrated with a 0.03 M NaOH solution to pH = 6 to obtain the disodium salt form. Acetonitrile, acetone, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), tetrahydrofuran (THF) and buffer salts were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Fair Lawn, NJ). Magnesium hydroxide (Mg(OH)2), glacial acetic acid, magnesium acetate, 1,8-bis-(dimethylamino)naphthalene (proton sponge), ammonium acetate (NH4Ac), formic acid (FA), and trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). All water was deionized and purified using a Millipore MILLI-Q™ water system.

2.2 Film Preparation and Storage

Films containing 0.3% w/w VYPNGA in PLGA were prepared as described in a previous publication [16] by dissolving 100 mg/mL polymer and 300 μg/mL peptide in acetone and sonicating for 30 min to enhance dissolution. Either 3% w/w (in relation to polymer) proton sponge (pKa =12.34), 3% w/w Mg(OH)2 (pKa = 9.5–10.5), or 0.13M NH4Ac (pKa = 7.0) was added to the formulation in an attempt to control pH in the degrading films [10]. Inclusion of an acetate buffer required the use of a co-solvent. Equimolar amounts of magnesium acetate and glacial acetic acid were dissolved in DMSO, then combined with the peptide and polymer in acetone to produce a 75/25 mixture of acetone/DMSO that was 0.15M in acetate buffer (pKa = 4.75). 0.5 mL aliquots of each solution were pipetted onto 22mm x 22mm glass coverslips and allowed to dry for approximately 18 hours. The volume of polymer solution and the surface area on which the films were cast were maintained constant, and consistent film mass was confirmed gravimetrically (data not shown). Acetate buffer films were dried at 80 °C and a vacuum of 4–5 atm for 2 hrs to remove DMSO. Films for 13C NMR analysis were prepared by dissolving ~ 15 mg/mL 13C disodium fumarate in DMSO and sonicating for 30 min. The solution was combined with the polymer/additive mixtures described above and vortexed. These films were aliquoted and dried under vacuum as described above to remove DMSO. Accelerated degradation studies were conducted at 70 °C and 95% relative humidity (%RH) achieved using a K2SO4 saturated salt solution. Triplicate samples were removed from storage at appropriate times based upon the expected degradation rate of either the peptide or polymer.

For peptide degradation analysis, films were dissolved and filtered as described previously [16]. Solid samples for NMR, DSC, and TGA analysis were removed from the glass coverslips with a razor blade. SEC samples were dissolved in 5 mL THF, producing samples with approximately 10 mg/mL PLGA.

2.3 Sample Analysis

2.31 13C Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (13C NMR)

Both solution and solid-state NMR (ssNMR) have been used to estimate the pH and effective ‘pH’ of solid and semi-solid systems based upon the chemical shift changes of an ionizable functional group[17, 18]. NMR is especially useful for establishing the protonation state and pKa of a functional group in either an organic solvent or in the solid-state[17, 18]. Here, 13C NMR was employed because carbon NMR typically provides a chemical shift difference on the order of several ppm upon protonation [18], compared to shifts < 1 ppm for proton NMR [19]. Fumaric acid was selected as a pH probe because the solution pKa’s of its two carboxylic acids (3.0 and 4.5) [20] fall within the range of pH values previously reported for PLGA matrices [10]. Adequate signal was obtained by solution NMR for all samples stored at 95% RH and 70 °C except the initial time point (t = 0).

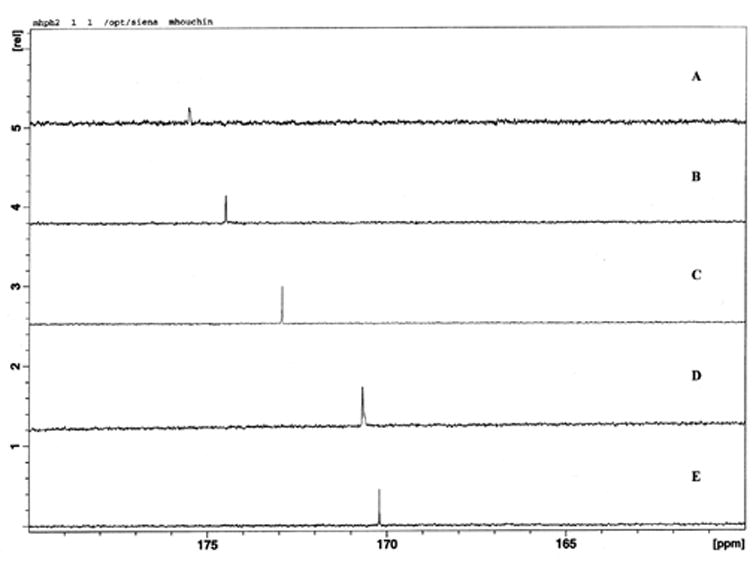

Films containing both PLGA and 13C disodium fumarate were rolled and placed in 5 mm solution NMR tubes. Samples were analyzed by 13C NMR spectroscopy using a Bruker Avance DRX 500 NMR spectrometer (Bruker, Billerica, MA) operating at 125.77 MHz for 13C. The spectrometer was equipped with a dual proton/carbon cryoprobe. The sweep width was 250 ppm and centered at 95 ppm. The experiments had a 1.04 sec acquisition time, a 0.15 second delay between scans, and a 30 degree excitation pulse. The number of scans per spectrum varied from 150 to 250. The experiments were run without lock, but were calibrated using non-deuterated DMSO as an internal standard. Carbonyl carbon chemical shift calibration (170–175 ppm) was performed using 2 mg/mL fumaric acid solutions, pH adjusted to values between 2.00 and 6.00 using 0.03 M NaOH solution. 10 μL/mL DMSO was added to each sample as an internal chemical shift standard (40.35 ppm). Parameters were as listed above, with the exception of a sweep width of 238.77 ppm, a 1.09 sec acquisition time and centered at 99.99 ppm. An example of the chemical shift changes observed during calibration is shown in Figure 1a.

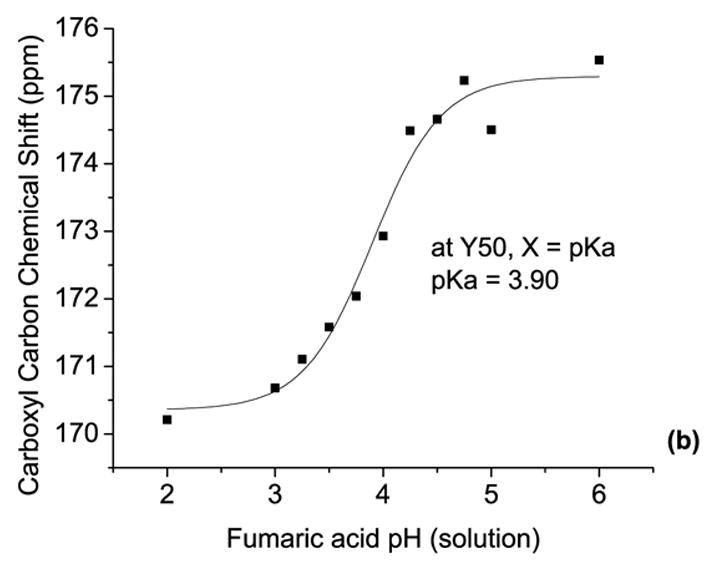

Figure 1.

NMR spectra and calibration curve. 13C NMR spectra of fumaric acid in solutions of pH 6.0 (A), 5.0(B), 4.0(C), 3.0(D) and 2.0(E)(a) calibration curve for solution NMR, relating chemical shift to solution pH (b).

A calibration curve was obtained by plotting the fumarate carboxyl carbon chemical shift versus solution pH, and fitting with a sigmoidal curve using Origin 7.0 (Microcal Software, Inc., MA), as shown in Figure 1b. Due to the relative time scales of fumaric acid protonation/deprotonation in solution and the solution NMR scanning rates, only the fully protonated and fully deprotonated forms could be identified based upon chemical shift. The pKa of fumarate was determined be 3.90, based on the midpoint of the sigmoidal calibration curve. This pKa is reasonable, as it is near the average pKa in solution (pKaave = (pKa1 + pKa2)/2 = (3.0 + 4.5)/2 = 3.75). Observed pH values based on these chemical shifts are reported as effective pH (‘pH’) values, since the initial state of the films is a low moisture content solid.

2.32 Peptide and Polymer Degradation Analysis

Product identification was accomplished by precursor and product ion scans, and chromatographic separations were performed using a Waters 2690 HPLC system (Milford, MA) with an Econosphere C18 reversed-phase column (4.6 x 250 mm, 5-μm particle size; Alltech Associates, Inc., Deerfield, IL) as described previously [16]. In short, product quantification was conducted using a gradient RP-HPLC method ranging from 1–30% acetonitrile at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The HPLC elution stream was split, sending 0.35 μL/min to the mass spectrometer and the rest to waste. Detection was performed using ESI+ tandem mass spectroscopy on a Micromass Quatro Micro Mass Spectrometer (Manchester, UK) with multiple reaction monitoring (MRM).

Thermogravimetric analysis using a Q 50 TGA (TA Instruments, New Castle, DE) was used to determine total sorbed water, as described previously [21]. Briefly, scans were conducted from 25 °C to 150 °C at a rate of 1 °C/min. The weight fraction of water was calculated as mg water/mg wet solid, and the weight of water was calculated using Universal Analysis software (TA Instruments).

Modulated temperature DSC using a Q 100 DSC with a refrigerated cooling system (TA Instruments, New Castle, DE) was used to measure matrix Tg as described previously [21]. MTDSC experiments used scan rates of 1 °C/min with modulation amplitudes ranging from ±0.2 to ±1 °C and modulation periods ranging from 30 to 60 sec. The glass transition temperature of the wet polymer mixture (Tgmix) was determined from the midpoint of the transition using the Universal Analysis TA Instruments software [22].

SEC analysis was performed using a Shimadzu HPLC system (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) and a Shimadzu SPD-6A UV detector with UV detection at 215nm as described previously [21]. Separation was conducted using THF with a flow rate of 0.8 mL/min and a Phenomenex Phenogel 5μ 103Å column (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA). Polystyrene narrow molecular weight standards were used for calibration.

2.4 Data Analysis

Nonlinear regression was performed using Origin 7.0 with instrumental error weighting (Microcal Software, Inc., MA). All peptide data were normalized as a percent of the initial (t = 0 hr) Asn-hexapeptide concentration prior to accelerated storage. As described previously, parent peptide loss kinetics were fit with a pseudo first-order rate equation [16]. ANOVA analysis was conducted with a p < 0.05, comparing PLGA degradation rates to evaluate the statistical similarity of slopes [23].

3. Results

3.1 Matrix pH

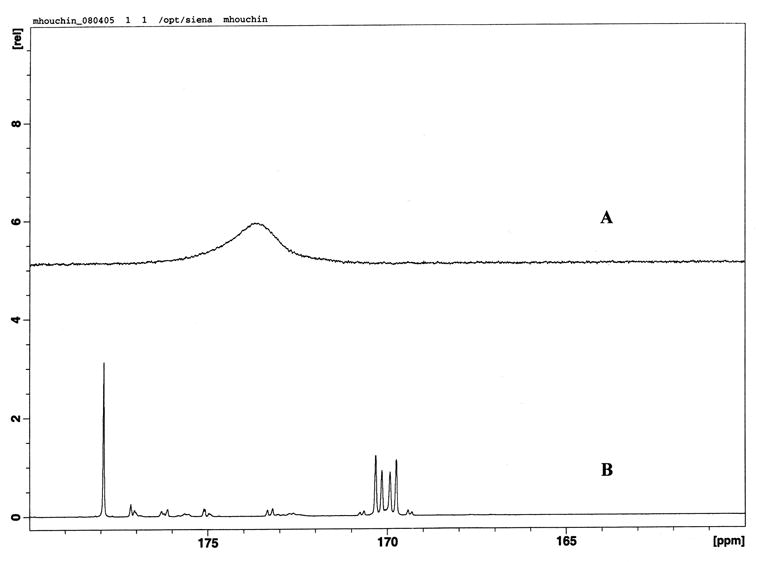

Fumarate was detectable using solution NMR after storage for 24 hours at 70 °C and 95% RH. At early storage times, only chemical shifts corresponding to disodium fumarate were visible (Figure 2a), indicating that the probe molecule was in a more mobile, preferentially hydrated environment than the polymer. At late storage times, both polymer and probe chemical shifts were detectable. Fumarate and polymer carboxyl carbons could still be differentiated at this stage due to 13C-13C splitting (Figure 2b) that is only observed in universally 13C labeled compounds [24]. Using the calibration curve (Fig. 1b), the chemical shifts were converted to pH and plotted versus storage time for the pH modified films and the unbuffered control (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

NMR spectra of 13C sodium fumarate in PLGA films. At low matrix mobility and moisture, only the carboxyl carbon fumarate peak is visible by solution NMR (storage for 23 hrs at 95% RH and 70 °C) (A) whereas at high mobility and moisture, both PLGA (~178ppm) and fumarate (~170ppm) carboxyl carbons are visible (storage for 95 hrs at 95% RH and 70 °C) (B). The peaks can be differentiated because only the fumarate carbons experience 13C-13C splitting as described in the text.

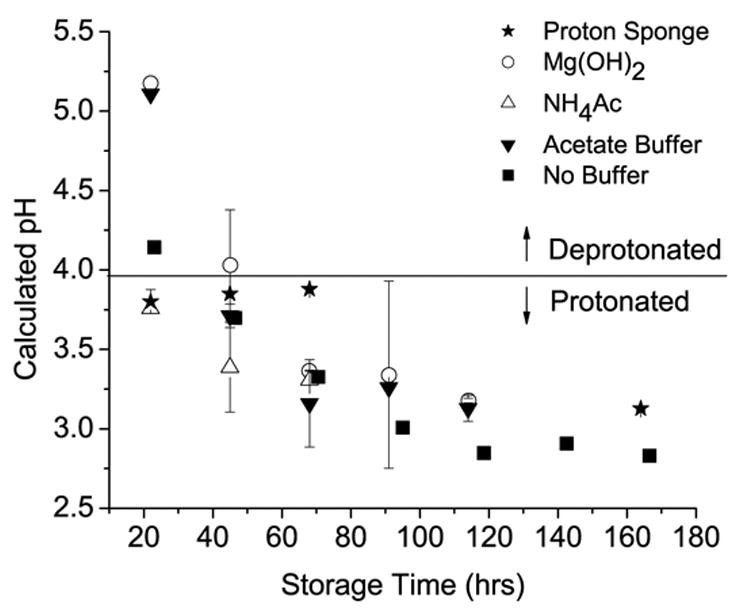

Figure 3.

Plot of solution NMR data versus storage time at 70 °C and 95% RH. Calculated pH is derived from the calibration curve shown in Fig. 1b. A line indicating the pKa of the fumarate probe is included to show under which conditions the probe is protonated or deprotonated.

As shown in Figure 3 for the PLGA film with no buffers or additives, the pH is already in the acidic range after 1 day of storage at 95% RH and 70 °C, but above the pKa of fumarate. After 2 days of storage, the pH is below the pKa, indicating that a majority of the probe molecules in the PLGA matrix are fully protonated. The calculated pH value continues to drop, falling below the limits of detection for this method (~ pH = 3, Fig. 1b). The proton sponge differed from the other additives by maintaining the matrix pH slightly below the pKa of fumarate for several days (Fig. 3). Inclusion of Mg(OH)2 delayed the drop in pH below the fumarate pKa by an additional 24 hrs compared to the unbuffered control. The addition of NH4Ac did not have the desired buffering effect on the PLGA films. Instead, NH4Ac actually reduced the pH of the films relative to the unbuffered control after 1 day of storage. The acetate buffer was initially (~ 24 hrs) as effective at buffering the film pH as Mg(OH)2. However, the pH in the acetate buffered films also fell below the pKa of the fumarate pH probe after 48 hrs of storage.

3.2 Peptide Degradation Products

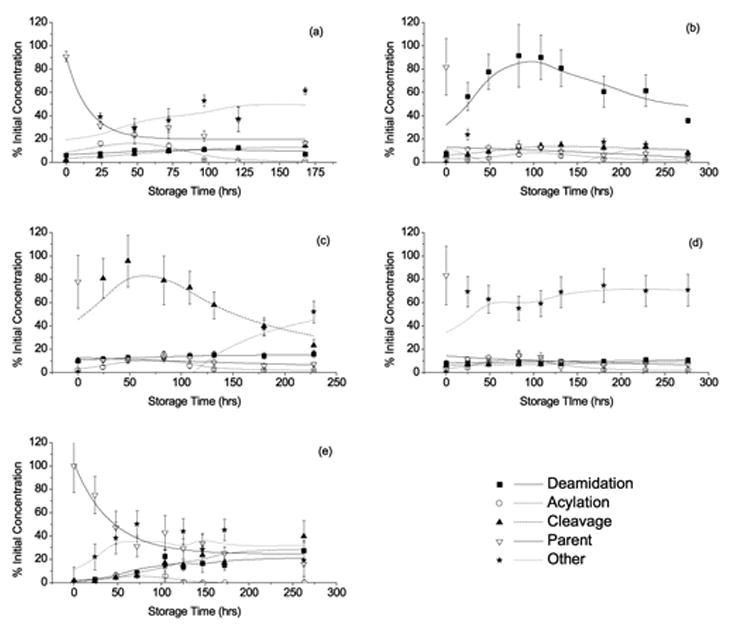

All peptide degradation products were identified in peptide-loaded films by RP-HPLC elution times [15] and by mass spectrometry product and precursor scans using previously developed methods [16]. Deamidation products identified were cyclic imide (Asu-), Asp- and in the Mg(OH)2 films, isoAsp-hexapeptide. Acylation products were lactoyl-Asu-hexapeptide (Lac-Asu), glycoloyl-Asu-hexapeptide (Gly-Asu) and lactoyl-Asp-hexapeptide (Lac-Asp). The Asp-catalyzed cleavage product, VYPD (tetrapeptide), and the general acid catalyzed product, alanine, were also detected. In the following discussion, the products will be categorized by reaction type as listed above. The major products for each pH modifier and each type of peptide degradation are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Major peptide degradation products for pH modified films and the unbuffered control. Times at which these products reached this maximum are variable, and can be observed in Figure 4. Degradation products are separated by reaction type, and the percent of that product relative to the initial peptide concentration is listed. Positive and negative signs indicate the change in this type of product relative to the unbuffered control.

| Deamidation | %* | ± | Cleavage | % | ± | Acylation | % | ± | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proton Sponge | Asu | 7.7 ±0.85 | − | VYPD | 7.3 ±0.68 | − | Lac-Asu | 22 ±8.3 | + |

| Magnesium Hydroxide | Asu** | 83 ±18 | + | VYPD | 9.7 ±2.0 | − | Lac-Asu | 10 ±2.0 | + |

| Ammonium Acetate | Asu | 10 ±1.8 | − | Alanine | 78 ±20 | + | Lac-Asu | 13 ±2.6 | + |

| Acetate Buffer | Asu | 5.5 ±1.1 | − | VYPD | 3.8 ±0.73 | − | Lac-Asu | 12 ±2.9 | + |

| Control | Asu | 24 ±6.6 | VYPD | 28 ±12 | Lac-Asu | 5.1 ±2.7 |

± values indicate the standard deviation, n = 7, 9, 8, 9 and 10, respectively.

The initial deamidation product was iso-Asp, which reached a maximum of 27(± 5.2)% of the initial peptide concentration after 24hrs of storage.

Figure 4a–d shows the time course of peptide degradation in each type of pH modified film. The degradation of VYPNGA in non-buffered PLGA films stored at 95%RH and 70 °C, presented previously [16], is shown in Figure 4e as a control. The proton sponge increased peptide degradation relative to the control (kobs = 6.5 x 10 −2 hr−1 and 9.2 x 10 −3 hr−1 respectively, but to a lesser degree that the other additives (Fig. 4a). The parent peptide loss in films containing the additives Mg(OH)2, NH4Ac and acetate buffer (Fig. 4b,c,d) is dramatically increased in comparison to the control formulation. VYPNGA concentration fell to 10% of the initial value after 24hrs of storage for each formulation, showing that these pH additives further destabilized the incorporated peptide. The rates of peptide loss in the other modified formulations could not be determined due to the immediate decline in parent peptide concentration upon storage. Attempts to fit the data to a pseudo first-order equation resulted in standard errors that were significantly greater than the rate constants themselves.

Figure 4.

Degradation profiles of the PLGA incorporated Asn-hexapeptide upon storage at 70°C and 95%RH, containing the following pH modifiers: Proton sponge (a), Mg(OH)2 (b), NH4Ac (c), Acetate buffer (d) and the no buffer control[16] (e). Lines for Asn-hexapeptide loss represent non-linear regression fits to a first order rate loss. Other lines represent adjacent averaging and are included to show product formation trends.

3.3 Polymer Physical Characterization

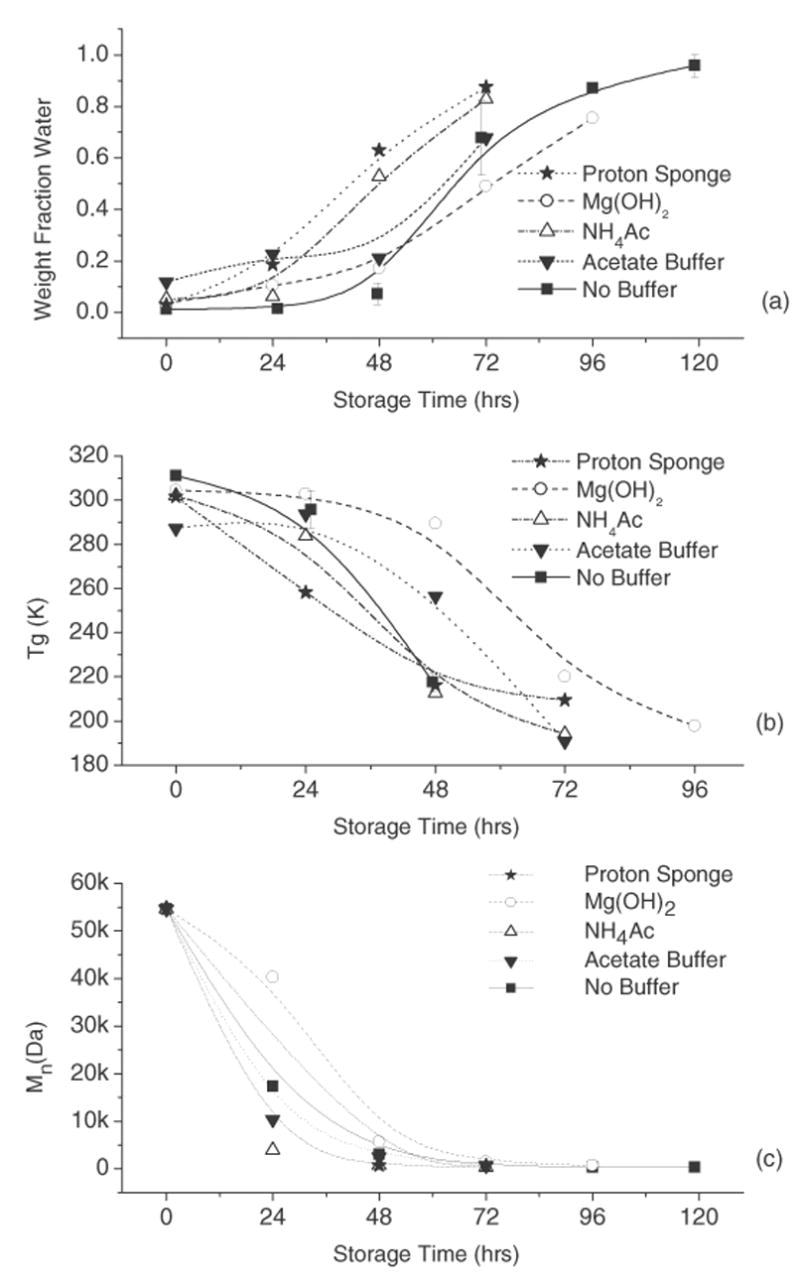

The physical properties of PLGA are shown in Figure 5. The weight fraction of water absorbed by the PLGA films, determined by TGA, is shown as a function of storage time in Figure 5a. As reported previously, PLGA water sorption in the absence of buffers is sigmoidal and shows a lag in initial water uptake [21]. In contrast to similar studies involving the addition of basic salts [10, 13], the addition of pH modifiers had little effect on water absorption. This difference likely stems from the accelerated conditions (70 °C) employed in this study, leading to increased PLGA degradation rates (see Figure 5c) compared to studies conducted at 37 °C [10, 13]. As shown in Figure 5a, water sorption increased slightly with the addition of proton sponge and NH4Ac, shortening the lag time of water uptake from 48 to 24 hrs. Mg(OH)2 slightly decreased the absorption of water at intermediate storage times (48–72hrs). The acetate buffer had very little effect on water sorption as a function of time. PLGA matrix Tg, determined by DSC, is shown as a function of storage time in Figure 5b. As expected, the matrix Tg decreased for all formulation types upon storage [21, 25]. Like water sorption data, the pH modifiers had little effect on the rate or amount of change in matrix Tg. Most notably, films containing Mg(OH)2 initially (0–24hrs) experienced a decreased rate of Tg change in comparison to the unbuffered films. PLGA number-average molecular weight (Mn), as determined by SEC, is shown as a function of storage time in Figure 5c. The Mn of PLGA decreased with storage time for all conditions. As with sorbed water and Tg, Mg(OH)2 had the greatest effect, initially (0–24hrs) decreasing the rate of PLGA degradation. Overall, none of the changes in PLGA properties upon addition of pH modifiers were statistically significant.

Figure 5.

Plots of PLGA properties as a function of storage time at 70 °C and 95% RH. Weight fraction water sorbed by PLGA (a), glass transition temperature (Tgmix) of wet PLGA films (b) and a plot of the number-average molecular weight of PLGA (c).

4. Discussion

Various pH modifying additives were included in PLGA films to evaluate their positive and negative effects on the chemical stability of an incorporated model peptide under accelerated storage conditions. While some of the additives improved peptide chemical stability by reducing deamidation and chain cleavage, others accelerated deamidation, amide bond hydrolysis and/or acylation.

Although the proton sponge had the highest pKa of the additives studied, its inclusion in the PLGA films reduced the initial pH of the matrix in comparison to the unbuffered control (Fig. 3). The initial decrease in pH was unexpected due to the high pKa of the proton sponge; however, steric hindrance of the amines has been shown to limit the rate of proton uptake by a proton sponge [26]. The proton sponge was able to maintain the film ‘pH’, which remained unchanged through 72hrs of storage (Fig. 3). Interestingly, films containing the proton sponge showed increased peptide acylation compared to unbuffered films, reaching a maximum of ~ 20% after 48hrs of storage (Fig. 4a), a four-fold increase over the unbuffered control (Fig. 4e and Table 1). Preferential protonation of the proton sponge (pKa = 12.34), rather than protonation of the peptide primary amine (pKa = 9.72[27]), is a likely cause, since the peptide N-terminus is expected to be a better nucleophile in the unprotonated form [16, 28, 29]. The reduction in deamidation and cleavage products (~ 7% each) in comparison to the unbuffered control can also be attributed to preferential protonation of the proton sponge rather than the Asn side chain or backbone amide nitrogen, respectively, as these are acid catalyzed reactions [16].

The addition of Mg(OH)2 increased the pH of the PLGA films, as measured by 13C NMR (Fig.3). The pH of Mg(OH)2 solutions can vary from 9.5–10.5 [20], depending on concentration, which also changes as the film absorbs water upon storage. Thus, it is assumed that the pH in the Mg(OH)2 film is initially higher than can be quantitated using this method (Fig. 1b). The pH of Mg(OH)2 modified films fell below the pKa of fumarate after 72hrs of storage, presumably due to an accumulation of lactic and glycolic acid monomers formed by PLGA hydrolysis (pKa = 3.86 and 3.83 respectively), eventually producing more protons than the hydroxide can neutralize. The initial increase in pH was accompanied by a slight decrease in PLGA hydrolysis and water sorption in Mg(OH)2 films (Fig. 5a, c) and a slight increase in Tg (Fig. 5b). This minimal effect on PLGA properties is most likely due to reduced acid catalysis of PLGA hydrolysis due to the initial increase in film ‘pH’ [11, 13, 30, 31]. Peptide stability in Mg(OH)2 modified films also indicates that the pH was greater than in the control study. Inclusion of Mg(OH)2 resulted in increased deamidation compared to unbuffered films, reaching a maximum of ~ 80% of the initial peptide after 96hrs of storage (Fig. 4b and Table 1). Also, the deamidation product iso-Asp-hexapeptide (VYP-isoD-GA) was detected at early storage times, a product not observed in unbuffered films, and only observed at neutral to basic pH (pH > 5) in both solution and solid states [15]. The degree of acylation in Mg(OH)2 modified films was slightly increased relative to unbuffered films, suggesting that the pH may have approached the pKa of the primary amine, thus increasing the nucleophilic character of the peptide N-terminus.

Ammonium acetate films showed a lower initial pH than controls (Fig. 3). The undissociated NH4Ac complex could act as a nucleophile, attacking the PLGA ester bonds and increasing the rate of PLGA hydrolysis [32]. The minimal change in PLGA physical properties in NH4Ac modified films can be correlated with the measured ‘pH’. The nucleophilic attack of the ammonium acetate complex on the PLGA would increase the rate of PLGA ester degradation, resulting in increased water uptake (Fig. 5a) and decreased Tg and Mn (Figs. 5b,c). As for peptide stability, NH4Ac containing films showed increased amide bond cleavage in comparison to unbuffered films. The major cleavage product was alanine, which reached a maximum of ~ 80% of the initial peptide concentration after 72hrs of storage (Fig. 4c and Table 1). This result suggests that the initially undissociated NH4Ac complex increases PLGA degradation, as extensive chain cleavage resulting in individual amino acids has been associated with the accumulation of PLGA monomers [16, 33]. However, the degree of acylation in the NH4Ac films was slightly greater than in the control, which is unexpected for more acidic conditions [16].

Films containing magnesium acetate buffer showed a higher initial pH than the control. By using a buffer with a pKa closer to the expected pH of PLGA (1.8–3.0), a greater buffer capacity is expected than with a neutral or basic buffer. However, due to the high concentration of lactic and glycolic acid produced by the degrading polymer and the absence of sink conditions in this experiment, the buffering capacity apparently was not sufficient to maintain the film pH above the pKa of the fumarate probe after 48hrs of storage. While the ‘pH’ was initially less acidic (Fig. 3) than in unbuffered films and PLGA degradation was not significantly affected (Figs. 5a–c), an increase in peptide degradation was observed (Fig. 4d). Few degradation products could be quantitated using the previously developed mass spectroscopy MRM detection method [16] (Table 1). Thus, the cause of increased peptide degradation in this formulation is uncertain. A previous study of peptide degradation in a concentrated acetate salts resulted in N-terminal acetylation [34].

It should be noted that these studies were conducted at accelerated conditions intended to promote the degradation of both the PLGA films and the peptide. The performance of the pH modifying additives is expected to depend on these conditions, since temperature and moisture content will influence effective solubility and pKa values within the films. Studies under conditions representing the physiological conditions experienced by polymeric implants (37 °C, high moisture) and conventional storage conditions (e.g., 25 °C, ambient humidity) are needed to more fully assess the effects of these modifiers. Nevertheless, the results presented here demonstrate the potential for acceleration of chemical degradation reactions by additives intended to control pH in PLGA matrices.

5. Conclusions

The effect of pH modifiers on peptide and polymer degradation is complex. Basic salts, such as Mg(OH)2, can reduce acid catalyzed degradation of incorporated peptides and of the polymer itself. However, they can induce base catalyzed degradation reactions, as evidenced by the production of iso-Asp. Proton sponges or basic amines may be a more effective means of stabilizing acidic peptide degradation in PLGA films, as demonstrated by the reduction of deamidation and cleavage in this study. Yet, these additives can have undesired effects such as increased PLGA hydrolysis, leading to increased release rates. Modifying the pH of PLGA formulations does not prevent peptide-polymer acylation reactions, and can even increase acylation due to increased nucleophilicity of the peptide amine. Ultimately, reduced diffusion of acidic PLGA monomers, due to either experimental design or the size of the PLGA formulation, reduces the efficiency of pH modifiers, regardless of buffer capacity.

Table 2.

Observed pseudo first-order rate constants for the loss of VYPNGA in PLGA films containing various additives.

| kobs (hr−1) | Standard Error* | |

|---|---|---|

| Proton Sponge | 6.5 x 10 −2 | ±1.0 x 10 −3 |

| Mg(OH)2 | n/a† | n/a† |

| NH4Ac | n/a† | n/a† |

| Acetate Buffer | n/a† | n/a† |

| No Buffer | 9.2 x 10 −3 | ±3.5 x 10 −3 |

Values represent standard errors of the kobs values as determined by nonlinear regression.

Values could not be fit with a pseudo first-order equation

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by an NIH Biotechnology Training Grant and by the Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry at The University of Kansas. The authors would like to thank Todd Williams and Kathy Heppert for assistance with ESI+ MS/MS and LC/MS/MS method development, and Drs. Ronald Borchardt, Richard Schowen, and David Vander Velde for their helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Na DH, Lee KC, DeLuca PP. PEGylation of octreotide: II. Effect of N-terminal mono-PEGylation on biological activity and pharmacokinetics. Pharm Res. 2005;22(5):743–749. doi: 10.1007/s11095-005-2590-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwendeman SP. Recent advances in the stabilization of proteins encapsulated in injectable PLGA delivery systems. Crit Rev Ther Drug Carrier Syst. 2002;19(1):73–98. doi: 10.1615/critrevtherdrugcarriersyst.v19.i1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jiang G, Woo BH, Kang F, Singh J, DeLuca PP. Assessment of protein release kinetics, stability and protein polymer interaction of lysozyme encapsulated poly(D,L-lactide-co-glycolide) microspheres. J Control Release. 2002;79(1–3):137–145. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(01)00533-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tamber H, Johansen P, Merkle HP, Gander B. Formulation aspects of biodegradable polymeric microspheres for antigen delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2005;57(3):357–376. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calis S, Jeyanthi R, Tsai T, Mehta RC, DeLuca PP. Adsorption of salmon calcitonin to PLGA microspheres. Pharm Res. 1995;12(7):1072–1076. doi: 10.1023/a:1016278902839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim HK, Park TG. Microencapsulation of human growth hormone within biodegradable polyester microspheres: protein aggregation stability and incomplete release mechanism. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1999;65(6):659–667. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0290(19991220)65:6<659::aid-bit6>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van de Weert M, Hennink WE, Jiskoot W. Protein instability in poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) microparticles. Pharm Res. 2000;17(10):1159–1167. doi: 10.1023/a:1026498209874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cleland JL, Mac A, Boyd B, Yang J, Duenas ET, Yeung D, Brooks D, Hsu C, Chu H, Mukku V, Jones AJ. The stability of recombinant human growth hormone in poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) microspheres. Pharm Res. 1997;14(4):420–425. doi: 10.1023/a:1012031012367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ibrahim MA, Ismail A, Fetouh MI, Gopferich A. Stability of insulin during the erosion of poly(lactic acid) and poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) microspheres. J Control Release. 2005;106(3):241–252. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shenderova A, Burke TG, Schwendeman SP. The acidic microclimate in poly(lactide-co-glycolide) microspheres stabilizes camptothecins. Pharm Res. 1999;16(2):241–248. doi: 10.1023/a:1018876308346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ara M, Watanabe M, Imai Y. Effect of blending calcium compounds on hydrolytic degradation of poly(DL-lactic acid-co-glycolic acid) Biomaterials. 2002;23(12):2479–2483. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(01)00382-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marinina J, Shenderova A, Mallery SR, Schwendeman SP. Stabilization of vinca alkaloids encapsulated in poly(lactide-co-glycolide) microspheres. Pharm Res. 2000;17(6):677–683. doi: 10.1023/a:1007522013835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang Y, Zale S, Sawyer L, Bernstein H. Effects of metal salts on poly(DL-lactide-co-glycolide) polymer hydrolysis. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 1997;34(4):531–538. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(19970315)34:4<531::aid-jbm13>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johansen P, Men Y, Audran R, Corradin G, Merkle HP, Gander B. Improving stability and release kinetics of microencapsulated tetanus toxoid by co-encapsulation of additives. Pharm Res. 1998;15(7):1103–1110. doi: 10.1023/a:1011998615267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Song Y, Schowen RL, Borchardt RT, Topp EM. Effect of ‘pH’ on the rate of asparagine deamidation in polymeric formulations: ‘pH’-rate profile. J Pharm Sci. 2001;90(2):141–156. doi: 10.1002/1520-6017(200102)90:2<141::aid-jps5>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Houchin ML, Heppert KE, Topp EM. Deamidation, acylation and proteolysis of a model peptide in PLGA films. J Control Release. 2006;112(1):111–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henry B, Tekely P, Delpuech JJ. pH and pK determinations by high-resolution solid-state 13C NMR: acid-base and tautomeric equilibria of lyophilized L-histidine. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124(9):2025–2034. doi: 10.1021/ja011638t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li J, Chatterjee K, Medek A, Shalaev E, Zografi G. Acid-base characteristics of bromophenol blue-citrate buffer systems in the amorphous state. J Pharm Sci. 2004;93(3):697–712. doi: 10.1002/jps.10580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joshi AB, Sawai M, Kearney WR, Kirsch LE. Studies on the mechanism of aspartic acid cleavage and glutamine deamidation in the acidic degradation of glucagon. J Pharm Sci. 2005;94(9):1912–1927. doi: 10.1002/jps.20405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Windholz M, Badavari S, Stroumtsos LY, Fertig MN. The Merck Index. Merck and Co. Inc; Rahway, NJ: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Houchin ML. Chemical stability of a model peptide in poly(lactide-co-glycolide) films. Dissertation, The University of Kansas; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schubnell M, Schawe JE. Quantitative determination of the specific heat and the glass transition of moist samples by temperature modulated differential scanning calorimetry. Int J Pharm. 2001;217(1–2):173–181. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(01)00601-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zar JH. Biostatistical Analysis. Prentice Hall; Upper Saddle River, NJ: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Silverstein RM, Webster FX. Spectrometric Identification of Organic Compounds. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blasi P, D’Souza SS, Selmin F, DeLuca PP. Plasticizing effect of water on poly(lactide-co-glycolide) J Control Release. 2005;108(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raab V, Gauchenova E, Merkoulov A, Harms K, Sundermeyer J, Kovacevic B, Maksic ZB. 1,8-Bis(hexamethyltriaminophosphazenyl)napthalene, HMPN: A superbasic bisphosphazene “proton sponge”. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127(45):15738–15743. doi: 10.1021/ja052647v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harris DC. Quantitative Chemical Analysis. W. H. Freeman and Company; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murty SB, Goodman J, Thanoo BC, DeLuca PP. Identification of chemically modified peptide from poly(D,L-lactide-co-glycolide) microspheres under in vitro release conditions. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2003;4(4):E50. doi: 10.1208/pt040450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murty SB, Na DH, Thanoo BC, DeLuca PP. Impurity formation studies with peptide-loaded polymeric microspheres Part II. In vitro evaluation. Int J Pharm. 2005;297(1–2):62–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2005.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Siepmann J, Elkharraz K, Siepmann F, Klose D. How autocatalysis accelerates drug release from PLGA-based microparticles: a quantitative treatment. Biomacromolecules. 2005;6(4):2312–2319. doi: 10.1021/bm050228k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhu G, Mallery SR, Schwendeman SP. Stabilization of proteins encapsulated in injectable poly (lactide- co-glycolide) Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18(1):52–57. doi: 10.1038/71916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith MB, March J. Advanced Organic Chemistry: Reactions, Mechanisms, and Structure. Wiley-Interscience; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Park TG, Lu W, Crotts G. Importance of in vitro experimental conditions on protein release kinetics, stability and polymer degradation in protein encapsulated poly(D,L-lactic acid-co-glycolic acid) microspheres. J Control Release. 1995;33(2):211–222. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hall SC, Tan MM, Leonard JJ, Stevenson CL. Characterization and comparison of leuprolide degradation profiles in water and dimethyl sulfoxide. J Peptide Res. 1999;53(4):432–441. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3011.1999.00069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]